Béthune

Béthune (French pronunciation: [betyn] ; archaic Dutch: Betun and Bethwyn historically in English) is a city in northern France, sub-prefecture of the Pas-de-Calais department.

Béthune | |

|---|---|

Subprefecture and commune | |

Grand Place | |

Coat of arms | |

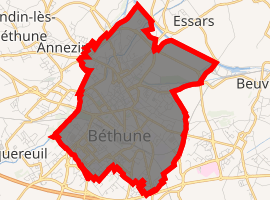

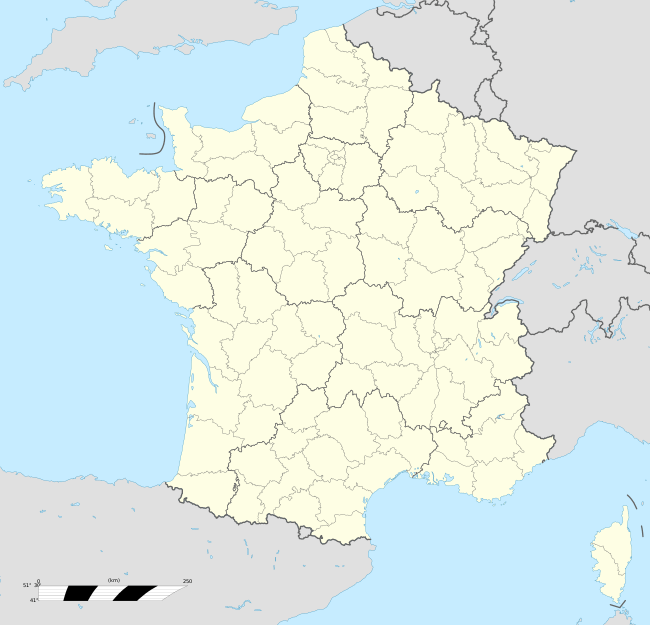

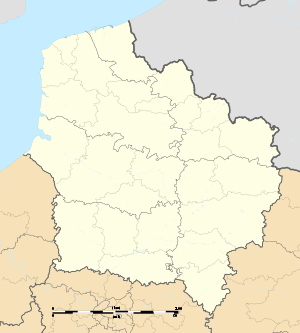

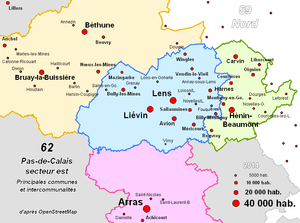

Location of Béthune

| |

Béthune  Béthune | |

| Coordinates: 50°31′49″N 2°38′27″E | |

| Country | France |

| Region | Hauts-de-France |

| Department | Pas-de-Calais |

| Arrondissement | Béthune |

| Canton | Béthune |

| Intercommunality | Communauté d'agglomération de Béthune-Bruay, Artois-Lys Romane |

| Government | |

| • Mayor (2014-2020) | Olivier Gacquerre |

| Area 1 | 9.43 km2 (3.64 sq mi) |

| Population (2017-01-01)[1] | 24,895 |

| • Density | 2,600/km2 (6,800/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| INSEE/Postal code | 62119 /62400 |

| Elevation | 18–42 m (59–138 ft) (avg. 26 m or 85 ft) |

| 1 French Land Register data, which excludes lakes, ponds, glaciers > 1 km2 (0.386 sq mi or 247 acres) and river estuaries. | |

Geography

Béthune is located in the former province of Artois. It is situated 73 kilometres (45 miles) south-east of Calais, 33 kilometres (21 miles) west of Lille, and 186 kilometres (116 miles) north of Paris.

Landmarks

Béthune is a town rich in architectural heritage and history. It has, among other features, a large paved square with shops, cafés, and a 47-metre-tall (154 ft) (133 steps) belfry standing in the center from the top of which the Belgian border can be seen. The chime of the belfry is composed of thirty-six bells. A belfry (French:"beffroi") has stood on the site since 1346.[2] The current belfry plays melodies every 15 minutes, including the ch'ti (regional patois) children's lullaby "min p'tit quinquin" (my little darling).[3]

History

.jpg)

Hugh Hastings (died 1347), King Edward III of England's captain and lieutenant in Flanders, mounted an attack and laid siege to Béthune, with a combined English and Flemish force, during a diversionary raid as part of Chevauchée of Edward III of 1346. The Flemish component proved undisciplined and the siege was abandoned in failure before the end of August.[4]

During the War of the Spanish Succession in July–August 1710, Béthune was besieged by forces of the Grand Alliance. The town eventually surrendered after a vigorous defence conducted by Antoine de Vauban (1654-1731), a relative of the famous military engineer Vauban.[5]

In 1914-1918, Béthune was an important railway junction and command centre for the British Canadian Corps and Indian Expeditionary Force, as well as the 33rd Casualty Station until December 1917. It initially suffered little damage until the second phase of the Ludendorff Offensive in April 1918, when German forces reached Locon, 5 km (3 mi) away. On 21 May, a bombardment destroyed large parts of the town, killing more than 100 civilians.[6] Over 3,200 casualties are buried in Béthune Town Cemetery, the Commonwealth section of which was designed by Edwin Lutyens; the majority are British (2,933) or Canadian (55), the remainder German.[7]

Rebuilt after the war, Béthune was badly damaged once more by air attacks and house to house fighting on 24–26 May 1940 when it was captured by the SS Panzer Division Totenkopf. The Totenkopf suffered heavy casualties and anger at their losses allegedly played a role in the Le Paradis massacre on 27 May, when 97 members of the Royal Norfolk Regiment were shot after surrendering.[8] During the war, many townspeople were deported to work in Germany; the town was officially liberated on 4 September 1944.[9]

Transport

The railway station has seven daily TGV trains to Paris, a journey which takes 1 hour 15 minutes. There are also regular trains to Lille, Amiens, Dunkerque and several regional destinations.

By car, Béthune is accessible from the A26 which intersects the A1 (Lille to Paris) 42 kilometres (26 miles) to the South-East. By road, it is 2 hours 30 minutes from Paris, 1 hour from Calais, 30 minutes from Arras and 40 minutes from Lille. By using the Channel Tunnel and the A26, Béthune is 3 hours 30 minutes from London and 6 hours 45 minutes from Manchester. Using road connections on mainland Europe it is nearly 2 hours from Brussels, 3 hours from Aix-La-Chapelle, 3 hours from Cologne, 8 hours 30 minutes from Berlin and 3 hours 30 minutes from Amsterdam.

Population

The inhabitants are called Béthunois.

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1793 | 6,932 | — |

| 1800 | 6,046 | −12.8% |

| 1806 | 6,379 | +5.5% |

| 1821 | 6,319 | −0.9% |

| 1831 | 6,889 | +9.0% |

| 1836 | 6,805 | −1.2% |

| 1841 | 7,448 | +9.4% |

| 1846 | 7,727 | +3.7% |

| 1851 | 7,692 | −0.5% |

| 1856 | 7,720 | +0.4% |

| 1861 | 8,264 | +7.0% |

| 1866 | 8,178 | −1.0% |

| 1872 | 8,410 | +2.8% |

| 1876 | 9,315 | +10.8% |

| 1881 | 10,374 | +11.4% |

| 1886 | 10,917 | +5.2% |

| 1891 | 11,098 | +1.7% |

| 1896 | 11,627 | +4.8% |

| 1901 | 12,404 | +6.7% |

| 1906 | 13,607 | +9.7% |

| 1911 | 15,309 | +12.5% |

| 1921 | 16,795 | +9.7% |

| 1926 | 20,141 | +19.9% |

| 1931 | 19,956 | −0.9% |

| 1936 | 20,073 | +0.6% |

| 1946 | 22,081 | +10.0% |

| 1954 | 22,376 | +1.3% |

| 1962 | 23,445 | +4.8% |

| 1968 | 27,154 | +15.8% |

| 1975 | 26,982 | −0.6% |

| 1982 | 25,508 | −5.5% |

| 1990 | 24,556 | −3.7% |

| 1999 | 27,808 | +13.2% |

| 2006 | 26,472 | −4.8% |

| 2009 | 25,766 | −2.7% |

| 2011 | 25,430 | −1.3% |

| 2015 | 24,995 | −1.7% |

Personalities

Béthune was the birthplace of:

- Jean Buridan, philosopher

- Antoine Busnois, composer and poet of the early Renaissance

- Jérôme Leroy, former captain of RC Lens and current FC Sochaux midfielder in France

- Pierre de Manchicourt, Renaissance composer

- Nicolas Fauvergue, footballer

- Thomas Crecquillon, the Renaissance composer, probably died here.

Béthune is also associated with the following historic personalities:

- Maximilien de Béthune, duc de Sully, general and statesman

- Conon de Béthune, crusader and trouvère poet

Sport

Stade Béthunois Football Club represent Béthune and was formed in 1902.[10] They currently play in Nord-Pas-de-Calais league.

International relations

Béthune is twinned with:

Gallery

References

- "Populations légales 2017". INSEE. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- "La ville de Béthune - Le beffroi de Béthune". Ville-bethune.fr. Archived from the original on 2010-02-24. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- "Dors min petit quinquin - Chblog, le blog chti". Chblog.com. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- Livingstone, Marilyn; Witzel, Morgen (2005). The Road to Crécy: The English Invasion of France, 1346. Harlow: Pearson Education. p. 143. ISBN 978-0582784208.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Reeve, JPF (1986). "The Siege of Bethune 1710: The Journals of Private Deane and General Vauban Compared". Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research. 64 (260): 205–211. JSTOR 44226494.

- "Bethune; Monuments aux Mortes". Memoires de Pierre. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- "Bethune; Monuments aux Mortes". Memoires de Pierre (in French). Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- Jackson, Julian (2003). The Fall Of France: The Nazi Invasion of 1940 (Making of the Modern World). Oxford University Press, U.S.A. pp. 301–302. ISBN 978-0192805508.

- "Béthune en 1939-1945". Ajpn.org. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- fr:Stade béthunois FC

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Béthune. |

- Béthune city council website (in French)

- Béthune on Heritage Towns

- "Histoire de Béthune" (in French)