Hindustani language

| Hindi edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

| Urdu edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

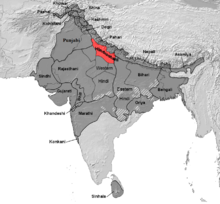

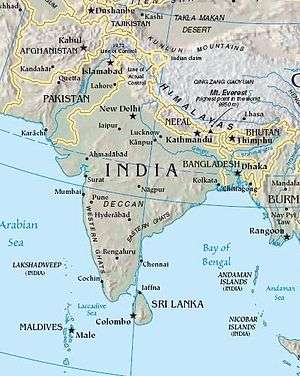

Hindustani (Hindi: हिन्दुस्तानी,[lower-alpha 1] Urdu: ہندوستانی,[lower-alpha 2][8]), colloquially known by some as Hamari/Apni Boli (lit. 'our language')[9][10] or Hindi-Urdu, and historically also known as Hindavi, Delhavi, and Rekhta, is the lingua franca of Northern India and Pakistan.[11][12] It is an Indo-Aryan language, deriving its base primarily from the Khariboli dialect of Delhi. The language incorporates a large amount of vocabulary from Prakrit, Persian and Arabic, as well as Sanskrit (via Prakrit and Tatsama borrowings). It is a pluricentric language, with two official forms, Modern Standard Hindi and Modern Standard Urdu,[13] which are its standardised registers. The colloquial registers are mostly indistinguishable, and even though the official standards are nearly identical in grammar, they differ in literary conventions and in academic and technical vocabulary, with Urdu adopting stronger Persian and Arabic influences, and Hindi relying more heavily on Sanskrit.[14] Before the partition of India, the terms Hindustani, Hindi, and Urdu were synonymous; they all covered what would be mostly called Hindi and Urdu today. The term Hindustani is still used for the colloquial language and the lingua franca of North India and Pakistan, for example for the language of Bollywood films, as well as for several languages of the Hindi-Urdu belt spoken outside the Indian subcontinent, such as Fijian Hindi of Fiji and the Caribbean Hindustani of Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana, Suriname, and the rest of the Caribbean. Hindustani is also spoken by a small number of people in Mauritius and South Africa.

History

Early forms of present-day Hindustani developed from the Middle Indo-Aryan apabhraṃśa vernaculars of present-day North India in the 7th–13th centuries.[15] Amir Khusrow, who lived in the thirteenth century during the Delhi Sultanate period in North India, used these forms (which was the lingua franca of the period) in his writings and referred to it as Hindavi (Persian: ھندوی literally "of Hindus or Indians").[15] The Delhi Sultanate, which comprised several Turkic and Afghan dynasties that ruled from Delhi,[16] was succeeded by the Mughal Empire in 1526.

Although the Mughals were of Timurid (Gurkānī) Turco-Mongol descent,[17] they were Persianised, and Persian had gradually become the state language of the Mughal empire after Babur,[18][19][20][21] a continuation since the introduction of Persian by Central Asian Turkic rulers in the Indian Subcontinent,[22] and the patronisation of it by the earlier Turko-Afghan Delhi Sultanate. The basis in general for the introduction of Persian into the subcontinent was set, from its earliest days, by various Persianised Central Asian Turkic and Afghan dynasties.[23]

In the 18th century, towards the end of the Mughal period, with the fragmentation of the empire and the elite system, a variant of Khariboli, one of the successors of apabhraṃśa vernaculars at Delhi, and nearby cities, came to gradually replace Persian as the lingua franca among the educated elite upper class particularly in northern India, though Persian still retained much of its pre-eminence for a short period. The term Hindustani (Persian: ھندوستانی "of Hindustan") was the name given to that variant of Khariboli.

For socio-political reasons, though essentially the variant of Khariboli with Persian vocabulary, the emerging prestige dialect became also known as Zabān-e Urdū-e Mualla "language of the court" or Zabān-e Urdū زبان اردو, ज़बान-ए उर्दू, "language of the camp" in Persian, derived from Turkic Ordū "camp", cognate with English horde, due to its origin as the common speech of the Mughal army). The more highly Persianised version later established as a language of the court was called Rekhta, or "mixed".

As an emerging common dialect, Hindustani absorbed large numbers of Persian, Arabic, and Turkic words, and as Mughal conquests grew it spread as a lingua franca across much of northern India. Written in the Persian alphabet or Devanagari,[24] it remained the primary lingua franca of northern India for the next four centuries (although it varied significantly in vocabulary depending on the local language) and achieved the status of a literary language, alongside Persian, in Muslim courts. Its development was centred on the poets of the Mughal courts of cities in Uttar Pradesh such as Delhi, Lucknow, and Agra.

John Fletcher Hurst in his book published in 1891 mentioned that the Hindustani or camp language of the Mughal Empire's courts at Delhi was not regarded by philologists as distinct language but only as a dialect of Hindi with admixture of Persian. He continued: "But it has all the magnitude and importance of separate language. It is linguistic result of Muslim rule of eleventh & twelfth centuries and is spoken (except in rural Bengal) by many Hindus in North India and by Musalman population in all parts of India". Next to English it was the official language of British Raj, was commonly written in Arabic or Persian characters, and was spoken by approximately 100,000,000 people.[25]

When the British colonised the Indian subcontinent from the late 18th through to the late 19th century, they used the words 'Hindustani', 'Hindi' and 'Urdu' interchangeably. They developed it as the language of administration of British India,[26] further preparing it to be the official language of modern India and Pakistan. However, with independence, use of the word 'Hindustani' declined, being largely replaced by 'Hindi' and 'Urdu', or 'Hindi-Urdu' when either of those was too specific. More recently, the word 'Hindustani' has been used for the colloquial language of Bollywood films, which are popular in both India and Pakistan and which cannot be unambiguously identified as either Hindi or Urdu.

Registers

Although, at the spoken level, Hindi and Urdu are considered registers of a single language, they differ vastly in literary and formal vocabulary; where literary Hindi draws heavily on Sanskrit and to a lesser extent Prakrit, literary Urdu draws heavily on Persian and Arabic. The grammar and base vocabulary (most pronouns, verbs, adpositions, etc.) of both Hindi and Urdu, however, are the same and derive from a Prakritic base, and both have Persian/Arabic influence.

The standardised registers Hindi and Urdu are collectively known as Hindi-Urdu. Hindustani is perhaps the lingua franca of the north and west of the Indian subcontinent, though it is understood fairly well in other regions also, especially in the urban areas. A common vernacular sharing characteristics with Sanskritised Hindi, regional Hindi and Urdu, Hindustani is more commonly used as a vernacular than highly Sanskritised Hindi or highly Arabicised/Persianised Urdu.

This can be seen in the popular culture of Bollywood or, more generally, the vernacular of North Indians and Pakistanis, which generally employs a lexicon common to both Hindi and Urdu speakers. Minor subtleties in region will also affect the 'brand' of Hindustani, sometimes pushing the Hindustani closer to Urdu or to Hindi. One might reasonably assume that the Hindustani spoken in Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh (known for its usage of Urdu) and Varanasi (a holy city for Hindus and thus using highly Sanskritised Hindi) is somewhat different.

Modern Standard Hindi

Standard Hindi, one of the official languages of India, is based on the Kharibol dialect of the Delhi region and differs from Urdu in that it is usually written in the indigenous Devanagari of India and exhibits less Persian and Arabic influence than Urdu. It has a literature of 500 years, with prose, poetry, religion and philosophy, under the Bahmani Kings and onwards. It is prevalent all over the Deccan Plateau. Note that the term Hindustani has generally fallen out of common usage in modern India, except to refer to "Indian" as a nationality[27] and a style of Indian classical music prevalent in northern India. The term used to refer to it is Hindi or Urdu, depending on the religion of the speaker, and regardless of the mix of Persian or Sanskrit words used by the speaker. One could conceive of a wide spectrum of dialects and registers, with the highly Persianised Urdu at one end of the spectrum and a heavily Sanskrit-based dialect, spoken in the region around Varanasi, at the other end. In common usage in India, the term Hindi includes all these dialects except those at the Urdu spectrum. Thus, the different meanings of the word Hindi include, among others:

- standardised Hindi as taught in schools throughout India (except some states such as Tamil Nadu),

- formal or official Hindi advocated by Purushottam Das Tandon and as instituted by the post-independence Indian government, heavily influenced by Sanskrit,

- the vernacular dialects of Hindustani as spoken throughout India,

- the neutralised form of Hindustani used in popular television and films, or

- the more formal neutralised form of Hindustani used in television and print news reports.

Modern Standard Urdu

Urdu is the national language of Pakistan and an officially recognised regional language of India. Urdu is the official language of all Pakistani provinces and is taught in all schools as a compulsory subject up to the 12th grade. It is also an official language in the Indian states of Jammu and Kashmir, National Capital Territory of Delhi, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Telangana that have significant Muslim populations.

Bazaar Hindustani

In a specific sense, Hindustani may be used to refer to the dialects and varieties used in common speech, in contrast with the standardised Hindi and Urdu. This meaning is reflected in the use of the term bazaar Hindustani, in other words, the "language of the street or the marketplace", as opposed to the perceived refinement of formal Hindi, Urdu, or even Sanskrit. Thus, the Webster's New World Dictionary defines the term Hindustani as the principal dialect of Hindi/Urdu, used as a trade language throughout north India and Pakistan.

Names

Amir Khusro ca. 1300 referred to this language of his writings as Dehlavi (देहलवी; دہلوی 'of Delhi') or Hindavi (हिन्दवी; ہندوی). During this period, Hindustani was used by Sufis in promulgating their message across the Indian subcontinent.[28] After the advent of the Mughals in the subcontinent, Hindustani acquired more Persian loanwords. Rekhta ('mixture') and Hindi ('Indian')[24] became popular names for the same language until the 18th century.[29] The name Urdu appeared around 1780.[29] During the British Raj, the term Hindustani was used by British officials.[29] In 1796, John Borthwick Gilchrist published a "A Grammar of the Hindoostanee Language".[29][30] Upon partition, India and Pakistan established national standards that they called Hindi and Urdu, respectively, and attempted to make distinct, with the result that Hindustani commonly, but mistakenly, came to be seen as a mixture of Hindi and Urdu.

Grierson, in his highly influential Linguistic Survey of India, proposed that the names Hindustani, Urdu, and Hindi be separated in use for different varieties of the Hindustani language, rather than as the overlapping synonyms they frequently were:

We may now define the three main varieties of Hindōstānī as follows:—Hindōstānī is primarily the language of the Upper Gangetic Doab, and is also the lingua franca of India, capable of being written in both Persian and Dēva-nāgarī characters, and without purism, avoiding alike the excessive use of either Persian or Sanskrit words when employed for literature. The name 'Urdū' can then be confined to that special variety of Hindōstānī in which Persian words are of frequent occurrence, and which hence can only be written in the Persian character, and, similarly, 'Hindī' can be confined to the form of Hindōstānī in which Sanskrit words abound, and which hence can only be written in the Dēva-nāgarī character.[31]

Literature

Official status

Hindi, a major standardized register of Hindustani, is declared by the Constitution of India as the "official language (राजभाषा, rājabhāśā) of the Union" (Art. 343(1)) (In this context, "Union" means the Federal Government and not the entire country – India has 23 official languages). At the same time, however, the definitive text of federal laws is officially the English text and proceedings in the higher appellate courts must be conducted in English. At the state level, Hindi is one of the official languages in 9 of the 29 Indian states and three Union Territories (respectively, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Jharkhand, Uttarakhand, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Chhattisgarh, Himachal Pradesh, and Haryana; Delhi, Chandigarh, and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands). In the remaining states Hindi is not an official language. In the states like Tamil Nadu and Karnataka, studying Hindi is not compulsory in the state curriculum. However an option to take the same as second or third language does exist. In many other states, studying Hindi is usually compulsory in the school curriculum as a third language (the first two languages being the state's official language and English), though the intensiveness of Hindi in the curriculum varies.[32]

Urdu, also a major standardized register of Hindustani, is also one of the languages recognized in the Eighth Schedule to the Constitution of India and is an official language of the Indian states of Telangana, Bihar, Delhi, Jammu and Kashmir, and Uttar Pradesh. Although the government school system in most other states emphasises Modern Standard Hindi, at universities in cities such as Lucknow, Aligarh and Hyderabad, Urdu is spoken and learnt, and Saaf or Khaalis Urdu is treated with just as much respect as Shuddha Hindi.

Urdu is also the national language of Pakistan, where it shares official language status with English. Although English is spoken by many, and Punjabi is the native language of the majority of the population, Urdu is the lingua franca.

Hindustani was the official language of the British Raj and was synonymous with both Hindi and Urdu.[26][33][34] After India's independence in 1947, the Sub-Committee on Fundamental Rights recommended that the official language of India be Hindustani: "Hindustani, written either in Devanagari or the Perso-Arabic script at the option of the citizen, shall, as the national language, be the first official language of the Union."[35] However, this recommendation was not adopted by the Constituent Assembly.

Hindustani outside South Asia

Besides being the lingua franca of North India and Pakistan in South Asia, Hindustani is also spoken by many in the South Asian diaspora and their descendants around the world, including North America (in Canada, for example, Hindustani is one of the fastest growing languages[36]), Europe, and the Middle East.

Hindustani was also one of the languages that was spoken widely during British rule in Burma. Many older citizens of Myanmar, particularly Anglo-Indians and the Anglo-Burmese, still know it, although it has had no official status in the country since military rule began.

Hindustani is also spoken in the countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council, where migrant workers from various countries live and work for several years.

Phonology

Grammar

Vocabulary

Hindustani contains around 5,500 words of Persian and Arabic origin.[37]

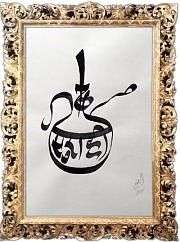

Writing system

Historically, Hindustani was written in the Kaithi, Devanagari, and Urdu alphabets.[24] Kaithi and Devanagari are two of the Brahmic scripts native to India, whereas Urdu is a derivation of the Persian Nastaʿlīq script, which is the preferred calligraphic style for Urdu.

Today, Hindustani continues to be written in the Urdu alphabet in Pakistan. In India, the Hindi register is officially written in Devanagari, and Urdu in the Urdu alphabet, to the extent that these standards are partly defined by their script.

However, in popular publications in India, Urdu is also written in Devanagari, with slight variations to establish a Devanagari Urdu alphabet alongside the Devanagari Hindi alphabet.

| अ | आ | इ | ई | उ | ऊ | ए | ऐ | ओ | औ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ə | aː | ɪ | iː | ʊ | uː | eː | ɛː | oː | ɔː |

| क | क़ | ख | ख़ | ग | ग़ | घ | ङ | ||

| k | q | kʰ | x | ɡ | ɣ | ɡʱ | ŋ | ||

| च | छ | ज | ज़ | झ | झ़ | ञ | |||

| t͡ʃ | t͡ʃʰ | d͡ʒ | z | d͡ʒʱ | ʒ | ɲ | |||

| ट | ठ | ड | ड़ | ढ | ढ़ | ण | |||

| ʈ | ʈʰ | ɖ | ɽ | ɖʱ | ɽʱ | ɳ | |||

| त | थ | द | ध | न | |||||

| t | tʰ | d | dʱ | n | |||||

| प | फ | फ़ | ब | भ | म | ||||

| p | pʰ | f | b | bʱ | m | ||||

| य | र | ल | व | ||||||

| j | ɾ | l | ʋ | ||||||

| श | ष | स | ह | ||||||

| ʃ | ʂ | s | ɦ | ||||||

| Letter | Name of letter | Transcription | IPA |

|---|---|---|---|

| ا | alif | – | – |

| ب | be | b | /b/ |

| پ | pe | p | /p/ |

| ت | te | t | /t/ |

| ٹ | ṭe | ṭ | /ʈ/ |

| ث | se | s | /s/ |

| ج | jīm | j | /d͡ʒ/ |

| چ | che | ch | /t͡ʃ/ |

| ح | baṛī he | h | /h ~ ɦ/ |

| خ | khe | kh | /x/ |

| د | dāl | d | /d/ |

| ڈ | ḍāl | ḍ | /ɖ/ |

| ذ | zāl | dh | /z/ |

| ر | re | r | /r ~ ɾ/ |

| ڑ | ṛe | ṛ | /ɽ/ |

| ز | ze | z | /z/ |

| ژ | zhe | zh | /ʒ/ |

| س | sīn | s | /s/ |

| ش | shīn | sh | /ʃ/ |

| ص | su'ād | ṣ | /s/ |

| ض | zu'ād | z̤ | /z/ |

| ط | to'e | t | /t/ |

| ظ | zo'e | ẓ | /z/ |

| ع | ‘ain | ' | – |

| غ | ghain | gh | /ɣ/ |

| ف | fe | f | /f/ |

| ق | qāf | q | /q/ |

| ک | kāf | k | /k/ |

| گ | gāf | g | /ɡ/ |

| ل | lām | l | /l/ |

| م | mīm | m | /m/ |

| ن | nūn | n | /n/ |

| و | vā'o | v, o, or ū | /ʋ/, /oː/, /ɔ/ or /uː/ |

| ہ, ﮩ, ﮨ | choṭī he | h | /h ~ ɦ/ |

| ھ | do chashmī he | h | /ʰ/ or /ʱ/ |

| ء | hamza | ' | /ʔ/ |

| ی | ye | y, i | /j/ or /iː/ |

| ے | baṛī ye | ai or e | /ɛː/, or /eː/ |

Because of anglicisation in South Asia and the international use of the Latin script, Hindustani is occasionally written in the Latin script. This adaptation is called Roman Urdu or Romanised Hindi, depending upon the register used. Because the Bollywood film industry is a major proponent of the Latin script, the use of Latin script to write in Hindi and Urdu is growing amongst younger Internet users. Since Urdu and Hindi are mutually intelligible when spoken, Romanised Hindi and Roman Urdu (unlike Devanagari Hindi and Urdu in the Urdu alphabet) are mutually intelligible as well.

Sample text

Following is a sample text, Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, in the two official registers of Hindustani, Hindi and Urdu. Because this is a formal legal text, differences in formal vocabulary are maximised.

Formal Hindi

- अनुच्छेद १ — सभी मनुष्यों को गौरव और अधिकारों के विषय में जन्मजात स्वतन्त्रता प्राप्त हैं। उन्हें बुद्धि और अन्तरात्मा की देन प्राप्त है और परस्पर उन्हें भाईचारे के भाव से बर्ताव करना चाहिये।

Nastaliq transcription:

انچھید ١ : سبھی منشیوں کو گورو اور ادھکاروں کے وشے میں جنمجات سؤتنترتا پراپت ہیں۔ انہیں بدھی اور انتراتما کی دین پراپت ہے اور پرسپر انہیں بھائی چارے کے بھاؤ سے برتاؤ کرنا چاہئے۔

Transliteration (IAST):

- Anucched 1: Sabhī manushyoṇ ko gaurav aur adhikāroṇ ke vishay meṇ janm'jāt svatantratā prāpt haiṇ. Unheṇ buddhi aur antarātmā kī den prāpt hai aur paraspar unheṇ bhāīchāre ke bhāv se bartāv karnā chāhiye.

Transcription (IPA):

- ənʊtʃʰːed ek səbʱi mənʊʂjõ ko ɡɔɾəʋ ɔr ədʱɪkaɾõ ke viʂaj mẽ dʒənmdʒat sʋətəntɾəta pɾapt hɛ̃ ʊnʱẽ bʊdʱːɪ ɔɾ əntəɾatma kiː den pɾapt hɛ ɔɾ pəɾəspəɾ ʊnʱẽ bʱaitʃaɾe keː bʱaʋ se bəɾtaʋ kəɾna tʃahɪe

Gloss (word-to-word):

- Article 1—All human-beings to dignity and rights' matter in from-birth freedom acquired is. Them to reason and conscience's endowment acquired is and always them to brotherhood's spirit with behaviour to do should.

Translation (grammatical):

- Article 1—All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

Formal Urdu

:دفعہ 1: تمام انسان آزاد اور حقوق و عزت کے اعتبار سے برابر پیدا ہوئے ہیں۔ انہیں ضمیر اور عقل ودیعت ہوئی ہیں۔ اسلئے انہیں ایک دوسرے کے ساتھ بھائی چارے کا سلوک کرنا چاہئے۔

Devanagari transcription:

- दफ़ा १ — तमाम इनसान आज़ाद और हुक़ूक़ ओ इज़्ज़त के ऐतबार से बराबर पैदा हुए हैं। इन्हें ज़मीर और अक़्ल वदीयत हुई हैं। इसलिए इन्हें एक दूसरे के साथ भाई चारे का सुलूक करना चाहीए।

Transliteration (ALA-LC):

- Dafʻah 1: Tamām insān āzād aur ḥuqūq o ʻizzat ke iʻtibār se barābar paidā hu’e haiṇ. Unheṇ zamīr aur ʻaql wadīʻat hu’ī he. Isli’e unheṇ ek dūsre ke sāth bhā’ī chāre kā sulūk karnā chāhi’e.

Transcription (IPA):

- dəfa ek təmam ɪnsan azad ɔɾ hʊquq o izːət ke ɛtəbaɾ se bəɾabəɾ pɛda hʊe hɛ̃ ʊnʱẽ zəmiɾ ɔɾ əql ʋədiət hʊi hɛ̃ ɪslɪe ʊnʱẽ ek dusɾe ke satʰ bʱai tʃaɾe ka sʊluk kəɾna tʃahɪe

Gloss (word-to-word):

- Article 1: All humans free[,] and rights and dignity's consideration from equal born are. To them conscience and intellect endowed is. Therefore, they one another's with brotherhood's treatment do must.

Translation (grammatical):

- Article 1—All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience. Therefore, they should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

Hindustani and Bollywood

The predominant Indian film industry Bollywood, located in Mumbai, Maharashtra uses Hindi, Khariboli dialect, Bombay Hindi, Urdu,[38] Awadhi, Rajasthani, Bhojpuri, and Braj Bhasha, along with the language of Punjabi and with the liberal use of English or Hinglish for the dialogue and soundtrack lyrics.

Movie titles are often screened in three scripts: Latin, Devanagari and occasionally Perso-Arabic. The use of Urdu or Hindi in films depends on the film's context: historical films set in the Delhi Sultanate or Mughal Empire are almost entirely in Urdu, whereas films based on Hindu mythology or ancient India make heavy use of Hindi with Sanskrit vocabulary.

Hindustani films and Lollywood

The Pakistani film industry Lollywood, centred historically in Lahore, has seen a rise in Punjabi movies lately. The Hindustani language films have seen a surge throughout Pakistan specifically Karachi, with new age films, and to a lesser extent in Islamabad and Lahore.

See also

Notes

References

- ↑ "Report of the Commissioner for linguistic minorities: 50th report (July 2012 to June 2013)" (PDF). Commissioner for Linguistic Minorities, Ministry of Minority Affairs, Government of India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2016. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- 1 2 "Hindi" L1: 260 million (2001 census), including perhaps 100 million speakers of other languages that report their language as "Hindi" on the census. L2: 274 million (2016, source unknown). Urdu L1: 69 million (2001 census – 2015), L2: 94 million (1999, source unknown): Ethnologue 21. Hindi at Ethnologue (21st ed., 2018). Urdu at Ethnologue (21st ed., 2018).

- ↑ Takkar, Gaurav. "Short Term Programmes". punarbhava.in.

- ↑ "Fiji Constitution".

- ↑ The Central Hindi Directorate regulates the use of Devanagari and Hindi spelling in India. Source: Central Hindi Directorate: Introduction Archived 15 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "National Council for Promotion of Urdu Language". www.urducouncil.nic.in.

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Hindustani". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ "About Hindi-Urdu". North Carolina State University. Archived from the original on 15 August 2009. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- ↑ "Hamari Boli - The Hindi Urdu Flagship at the University of Texas at Austin". hindiurduflagship.org.

- ↑ "Drawn from the same wellspring - The Express Tribune". 14 May 2016.

- ↑ Mohammad Tahsin Siddiqi (1994), Hindustani-English code-mixing in modern literary texts, University of Wisconsin,

... Hindustani is the lingua franca of both India and Pakistan ...

- ↑ Lydia Mihelič Pulsipher; Alex Pulsipher; Holly M. Hapke (2005), World Regional Geography: Global Patterns, Local Lives, Macmillan, ISBN 0-7167-1904-5,

... By the time of British colonialism, Hindustani was the lingua franca of all of northern India and what is today Pakistan ...

- ↑ Robert E. Nunley; Severin M. Roberts; George W. Wubrick; Daniel L. Roy (1999), The Cultural Landscape an Introduction to Human Geography, Prentice Hall, ISBN 0-13-080180-1,

... Hindustani is the basis for both languages ...

- ↑ Kachru, Yamuna (2006). Hindi. John Benjamins Publishing. p. 2. ISBN 90-272-3812-X.

- 1 2 Keith Brown; Sarah Ogilvie (2008), Concise Encyclopedia of Languages of the World, Elsevier, ISBN 0-08-087774-5,

Apabhramsha seemed to be in a state of transition from Middle Indo-Aryan to the New Indo-Aryan stage. Some elements of Hindustani appear ... the distinct form of the lingua franca Hindustani appears in the writings of Amir Khusro (1253–1325), who called it Hindwi[.]

- ↑ Gat, Azar; Yakobson, Alexander (2013). Nations: The Long History and Deep Roots of Political Ethnicity and Nationalism. Cambridge University Press. p. 126. ISBN 978-1-107-00785-7.

- ↑ Zahir ud-Din Mohammad (2002-09-10), Thackston, Wheeler M., ed., The Baburnama: Memoirs of Babur, Prince and Emperor, Modern Library Classics, ISBN 0-375-76137-3,

Note: Gurkānī is the Persianized form of the Mongolian word "kürügän" ("son-in-law"), the title given to the dynasty's founder after his marriage into Genghis Khan's family.

- ↑ B.F. Manz, "Tīmūr Lang", in Encyclopaedia of Islam, Online Edition, 2006

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica, "Timurid Dynasty", Online Academic Edition, 2007. (Quotation: "Turkic dynasty descended from the conqueror Timur (Tamerlane), renowned for its brilliant revival of artistic and intellectual life in Iran and Central Asia. ... Trading and artistic communities were brought into the capital city of Herat, where a library was founded, and the capital became the centre of a renewed and artistically brilliant Persian culture.")

- ↑ "Timurids". The Columbia Encyclopedia (Sixth ed.). New York City: Columbia University. Archived from the original on 5 December 2006. Retrieved 8 November 2006.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica article: Consolidation & expansion of the Indo-Timurids, Online Edition, 2007.

- ↑ Bennett, Clinton; Ramsey, Charles M. (2012). South Asian Sufis: Devotion, Deviation, and Destiny. A&C Black. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-4411-5127-8.

- ↑ Laet, Sigfried J. de Laet (1994). History of Humanity: From the seventh to the sixteenth century. UNESCO. p. 734. ISBN 978-92-3-102813-7.

- 1 2 3 Pollock, Sheldon (2003). Literary Cultures in History: Reconstructions from South Asia. University of California Press. p. 912. ISBN 978-0-520-22821-4.

- ↑ Hurst, John Fletcher (1992). Indika, The country and People of India and Ceylon. Concept Publishing Company. p. 344. GGKEY:P8ZHWWKEKAJ.

- 1 2 Coulmas, Florian (2003). Writing Systems: An Introduction to Their Linguistic Analysis. Cambridge University Press. p. 232. ISBN 978-0-521-78737-6.

- ↑ Bahri, (13 February 1989). "Learners' Hindi-English Dictionary". dsalsrv02.uchicago.edu.

- ↑ "The Origin and Growth of Urdu Language". Yaser Amri. Retrieved 2007-01-08.

- 1 2 3 4 Faruqi, Shamsur Rahman (2003), "A Long History of Urdu Literarature, Part 1", Literary cultures in history: reconstructions from South Asia, p. 806, ISBN 978-0-520-22821-4 in Pollock (2003).

- ↑ A Grammar of the Hindoostanee Language, Chronicle Press, 1796, retrieved 2007-01-08

- ↑ Grierson, vol. 9-1, p. 47.

- ↑ Government of India: National Policy on Education Archived 20 June 2006 at the Wayback Machine..

- ↑ "Colonial Knowledge and the Fate of Hindustani". 35. Cambridge University Press: 665–682. JSTOR 179178.

- ↑ Coward, Harold (2003). Indian Critiques of Gandhi. SUNY Press. p. 218. ISBN 978-0-7914-5910-2.

- ↑ "Hindi, not a national language: Court".

- ↑ "Census data shows Canada increasingly bilingual, linguistically diverse".

- ↑ Kuczkiewicz-Fraś, Agnieszka (2008). Perso-Arabic Loanwords in Hindustani. Kraków: Księgarnia Akademicka. p. X. ISBN 978-83-7188-161-9.

- ↑ "Decoding the Bollywood poster". National Science and Media Museum. 28 February 2013.

Bibliography

- Asher, R. E. (1994). Hindi. In Asher (Ed.) (pp. 1547–1549).

- Asher, R. E. (Ed.). (1994). The Encyclopedia of language and linguistics. Oxford: Pergamon Press. ISBN 0-08-035943-4.

- Bailey, Thomas G. (1950). Teach yourself Hindustani. London: English Universities Press.

- Chatterji, Suniti K. (1960). Indo-Aryan and Hindi (rev. 2nd ed.). Calcutta: Firma K.L. Mukhopadhyay.

- Dua, Hans R. (1992). Hindi-Urdu as a pluricentric language. In M. G. Clyne (Ed.), Pluricentric languages: Differing norms in different nations. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-012855-1.

- Dua, Hans R. (1994a). Hindustani. In Asher (Ed.) (pp. 1554).

- Dua, Hans R. (1994b). Urdu. In Asher (Ed.) (pp. 4863–4864).

- Rai, Amrit. (1984). A house divided: The origin and development of Hindi-Hindustani. Delhi: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-561643-X.

- Further reading

- Henry Blochmann (1877). English and Urdu dictionary, romanized (8 ed.). CALCUTTA: Printed at the Baptist mission press for the Calcutta school-book society. p. 215. Retrieved 2011-07-06. the University of Michigan

- John Dowson (1908). A grammar of the Urdū or Hindūstānī language (3 ed.). LONDON: K. Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co., ltd. p. 264. Retrieved 2011-07-06. the University of Michigan

- John Dowson (1872). A grammar of the Urdū or Hindūstānī language. LONDON: Trübner & Co. p. 264. Retrieved 2011-07-06. Oxford University

- John Thompson Platts (1874). A grammar of the Hindūstānī or Urdū language. Volume 6423 of Harvard College Library preservation microfilm program. LONDON: W.H. Allen. p. 399. Retrieved 2011-07-06. Oxford University

- John Thompson Platts (1892). A grammar of the Hindūstānī or Urdū language. LONDON: W.H. Allen. p. 399. Retrieved 2011-07-06. the New York Public Library

- John Thompson Platts (1884). A dictionary of Urdū, classical Hindī, and English (reprint ed.). LONDON: H. Milford. p. 1259. Retrieved 2011-07-06. Oxford University

- Shakespear, John. A Dictionary, Hindustani and English. 3rd ed., much enl. London: Printed for the author by J.L. Cox and Son: Sold by Parbury, Allen, & Co., 1834.

- Taylor, Joseph. A dictionary, Hindoostanee and English. Available at Hathi Trust. (A dictionary, Hindoostanee and English / abridged from the quarto edition of Major Joseph Taylor ; as edited by the late W. Hunter ; by William Carmichael Smyth.)

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Hindi-Urdu_phrasebook. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Hindostani. |

- Bolti Dictionary (Hindustani)

- Hamari Boli (Hindustani)

- Khan Academy (Hindi-Urdu): academic lessons taught in Hindi-Urdu

- Hindi, Urdu, Hindustani, khaRî bolî

- Hindustani FAQ at the Wayback Machine (archived 27 October 2009)

- Hindustani as an anxiety between Hindi–Urdu Commitment

- Hindi? Urdu? Hindustani? Hindi-Urdu?

- Hindi/Urdu-English-Kalasha-Khowar-Nuristani-Pashtu Comparative Word List

- GRN Report for Hindustani

- Hindustani Poetry

- Hindustani online resources

- Biggest Hindustani-Indian poetry forum

- National Language Authority (Urdu), Pakistan (muqtadera qaumi zaban)

- "Language: Urdu and the borrowed words", Dawn.com