Nepali language

| Nepali | |

|---|---|

| Gorkhali | |

| नेपाली/गोरखाली | |

The word "Nepali" written in Devanagari | |

| Native to | Nepal |

| Ethnicity | Khas people[1] |

Native speakers | 16 million[2] |

|

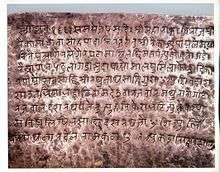

Devanagari Devanagari Braille Takri (historical) | |

| Signed Nepali | |

| Official status | |

Official language in |

|

| Regulated by | Nepal Academy |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 |

ne |

| ISO 639-2 |

nep |

| ISO 639-3 |

nep – inclusive codeIndividual codes: npi – Nepalidty – Doteli |

| Glottolog |

nepa1254[3]nepa1252 duplicate code[4] |

| Linguasphere |

59-AAF-d |

World map with significant Nepali language speakers Dark Blue: Main official language, Light blue: One of the official languages, Red: Places with significant population or greater than 20% but without official recognition. | |

Nepali (Devanagari: नेपाली) [1]also known as Khas Language is an Indo-Aryan language of the sub-branch of Eastern Pahari. It is the official language of Nepal and one of the 22 official language on India. It is spoken mainly in Nepal and by about a quarter of the population in Bhutan.[5] In India, Nepali is listed in the Eighth Schedule to the Constitution as an Indian language, with official status in the state of Sikkim, and spoken in Northeast Indian states such as Assam and in West Bengal's Darjeeling district. It is also spoken in Burma, Nepali diaspora worldwide.[6] Nepali developed in proximity to a number of Indo-Aryan languages, most notably the other Pahari languages and Maithili, and shows Sanskrit influence. However, owing to Nepal's location, it has also been influenced by Tibeto-Burman languages. Nepali is mainly differentiated from Central Pahari, both in grammar and vocabulary, by Tibeto-Burman idioms owing to close contact with this language group.[7]

Historically, the language was called Khas (Khas kurā) and Gorkhali (language of the Gorkha Kingdom) before the term Nepali was adopted.[1] The origin of modern Nepali language is believed to be from Sinja of Jumla. Therefore, the Nepali dialect “Khas Bhasa” is still spoken among the people of the region.[8]

It is also known as Khey (the native term for Khas Arya living in the periphery of the Kathmandu valley), Parbate (native term meaning "of the hill") or Partya among the Newar people, and Pahari among the Madhesis and Tharus. Other names include Dzongkha Lhotshammikha ("Southern Language", spoken by the Lhotshampas of Bhutan).

Literature

Nepali developed a significant literature within a short period of a hundred years in the 19th century. This literary explosion was fueled by Adhyatma Ramayana; Sundarananda Bara (1833); Birsikka, an anonymous collection of folk tales; and a version of the South Asian epic Ramayana by Bhanubhakta Acharya (d. 1868). The contribution of trio-laureates Lekhnath Paudyal, Laxmi Prasad Devkota, and Balkrishna Sama took Nepali to the level of other world languages. The contribution of expatriate writers outside Nepal, especially in Darjeeling and Varanasi in India, is also notable.

In the past decade, there have been many contributions to Nepali literature from the Nepali diaspora in Asia, Europe, America, and India.

Number of speakers

According to the 2011 national census, 44.6 percent of the population of Nepal speaks Nepali as a first language.[9] The Ethnologue website reports 12,300,000 speakers within Nepal (from the 2011 census).[10]

Nepali is traditionally spoken in the Hill Region of Nepal (Pahad, पहाड़), especially in the western part of the country. Although the Nepal Bhasha language dominated the Kathmandu valley, Nepali is currently the most dominant. Nepali is used in government and as the everyday language of a growing portion of the local population. Nevertheless, the exclusive use of Nepali in the courts and government of Nepal is being challenged. Recognition of other languages in Nepal was one of the objectives of the Communist Party of Nepal's long war.[11]

In Bhutan, those who speak Nepali, known as Lhotshampa, are estimated at about 35 percent [12] of the population. This number includes displaced Bhutanese refugees, with unofficial estimates of the ethnic Bhutanese refugee population as high as 30 to 40 percent, constituting a majority in the south (about 242,000 people).[13] Since the late 1980s, over 100,000 Lhotshampas have been forced out of Bhutan, accused by the government of being illegal immigrants.[12] A large portion of them were expelled in an ethnic cleansing campaign, and presently live in refugee camps in eastern Nepal.

There are 2.9 million Nepali language speakers in India, they reside in Sikkim, Darjeeling district and Northeast India.[14]

History

Around 500 years ago, Khas people from the Karnali-Bheri-Seti basin migrated eastward, bypassing inhospitable Kham highlands to settle in lower valleys of the Gandaki Basin that were well-suited to rice cultivation. One notable extended family settled in the Gorkha Kingdom, a small principality about halfway between Pokhara and Kathmandu. In 1559 AD a Lamjunge prince, Dravya Shah established himself on the throne of Gorkha with the help of local Khas and Magars. He raised an army of khas with the commandership of Bhagirath Panta. Later, in the late 18th century his heir Prithvi Narayan Shah raised and improvised an army of Chhetri, Thakuri, Magars and Gurung people and possibly other hill tribesmen and set out to conquer and consolidate dozens of small principalities in the Himalayan foothills. Since Gorkha had replaced the original Khas homeland, Khaskura was redubbed Gorkhali "language of the Gorkhas".

The most notable military achievement of Prithvi Narayan Shah was the conquest of the urbanized Kathmandu Valley, on the eastern rim of the Gandaki basin. This region was also called Nepal at the time. Kathmandu became Prithvi Narayan's new capital.

The Khas people originally referred to their language as Khas kurā ("Khas speech"), which was also known as Parbatiya (or Parbattia or Paharia, "language of the Hill country").[15][16] The Newar people used the term "Gorkhali" as a name for this language, as they identified it with the Gorkhali conquerors. The Gorkhalis themselves started using this term to refer to their language at a later stage.[17] The Census of India used the term Naipali at least from 1901 to 1951, the 1961 census replacing it with Nepali.[18][19]

Expansion – particularly to the north, west, and south – brought the growing state into conflict with the British and Chinese. This led to wars that trimmed back the territory to an area roughly corresponding to Nepal's present borders. Both China and Britain understood the value of a buffer state and did not attempt to further reduce the territory of the new country. After the Gorkha conquests, the Kathmandu Valley or Nepal became the new center of political initiative. As the entire conquered territory of the Gorkhas ultimately became 'Nepal', in the early decades of the 20th century, Gorkha language activists in India, especially Darjeeling and Varanasi, began petitioning Indian universities to adopt the name 'Nepali' for the language.[20] Also in an attempt to disassociate himself with his Khas background, the Rana monarch Jung Bahadur Rana decreed that the term Gorkhali be used instead of Khas kurā to describe the language. Meanwhile, the British Indian administrators had started using the term "Nepal" (after Newar) to refer to the Gorkha kingdom. In the 1930s, the Gorkha government also adopted this term to describe their country. Subsequently, the Khas language also came to be known as "Nepali language".[1] By the third decade, the Nepali state finally discontinued the use of the term Gorkhali, substituting it with Nepali, a move that provoked some stifled protest in Kathmandu from Newar intellectuals even during the autocratic Rana period.[21]

In all these years, Nepali has had influences from many languages. While Nepali is technically from the same family as languages like Hindi and Bengali, it has taken many loan words. Words like dhoka "door", jhyāl "window", pasal "shop", and rāngo "water buffalo' have Tibeto-Burmese roots. Words like sahīd "martyr" (ultimately from Arabic) and kānun "law" (ultimately from Greek, came from Persian into Nepali, as the former functioned as the literary language of much of the Muslim world for over a millennium). Many English words are in use today due to the rising popularity of the United States of America in the region and the previous British aid at schools and other fields.

Nepali is spoken indigenously over most of Nepal west of the Gandaki River, then progressively less further to the east.[22]

Dialects

Dialects of Nepali include Acchami, Baitadeli, Bajhangi, Bajurali, Bheri, Dadeldhuri, Dailekhi, Darchulali, Darchuli, Gandakeli, Humli, Purbeli, and Soradi.[10] Doteli (Dotyali) is a closely related language which is included in the macrolanguage Nepali.[23]

Phonology

In matters of script, Nepali uses Devanagari. On this grammar page Nepali is written in "standard orientalist" transcription as outlined in Masica (1991:xv). Being "primarily a system of transliteration from the Indian scripts, [and] based in turn upon Sanskrit" (cf. IAST), these are its salient features: subscript dots for retroflex consonants; macrons for etymologically, contrastively long vowels; h denoting aspirated plosives. Tildes denote nasalized vowels.

Vowels and consonants are outlined in the tables below. Hovering the mouse cursor over them will reveal the appropriate IPA symbol, while in the rest of the article hovering the mouse cursor over underlined forms will reveal the appropriate English translation.

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vowels

Monophthongs

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | i ĩ | u ũ | |

| Close-mid | e ẽ | o | |

| Open-mid | ʌ ʌ̃ | ||

| Open | a ã |

Nepali distinguishes six oral vowels and five nasal vowels. /o/ does not have a phonemic nasal counterpart, although it is often in free variation with [õ].

Diphthongs

Nepali possesses ten diphthongs: /ui/, /iu/, /ei/, /eu/, /oi/, /ou/, /ʌi/, /ʌu/, /ai/, and /au/.

Consonants

| Bilabial | Dental | Alveolar | Retroflex | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ | |||||||||||

| Stop | p pʰ |

b bʱ |

t tʰ |

d dʱ |

ts tsʰ |

dz dzʱ |

ʈ ʈʰ |

ɖ ɖʱ |

k kʰ |

ɡ ɡʱ |

||||

| Fricative | s | ɦ | ||||||||||||

| Rhotic | r | |||||||||||||

| Approximant | (w) | l | (j) | |||||||||||

[j] and [w] are nonsyllabic allophones of [i] and [u], respectively. Every consonant except [j], [w], /l/, and /ɦ/ has a geminate counterpart between vowels. /ɳ/ and /ʃ/ also exist in some loanwords such as /baɳ/ बाण "arrow" and /nareʃ/ नरेश "king", but these sounds are sometimes replaced with native Nepali phonemes.

Grammar

Writing

| Numeral | Written | IAST | IPA | Etymology | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | ० | शुन्य/सुन्ना | śūnya | /ʃunjʌ/ | Sanskrit śūnya (शून्य) |

| 1 | १ | एक | ek | /ek/ | Sanskrit eka (एक) |

| 2 | २ | दुई | duī | /d̪ui/ | Sanskrit dvi (द्वि) |

| 3 | ३ | तीन | tīn | /t̪in/ | Sanskrit tri (त्रि) |

| 4 | ४ | चार | cār | /t͡sar/ | Sanskrit catúr (चतुर्) |

| 5 | ५ | पाँच | pāṃc | /pãt͡s/ | Sanskrit pañca (पञ्च) |

| 6 | ६ | छ | cha | /t͡sʰʌ/ | Sanskrit ṣáṣ (षष्) |

| 7 | ७ | सात | sat | /sat̪/ | Sanskrit saptá (सप्त) |

| 8 | ८ | आठ | āṭh | /aʈʰ/ | Sanskrit aṣṭá (अष्ट) |

| 9 | ९ | नौ | nau | /nʌu/ | Sanskrit náva (नव) |

| 10 | १० | दश | daś | /d̪ʌs/ | Sanskrit dáśa दश |

| 11 | ११ | एघार | eghār | /eɡʱar/ | |

| 12 | १२ | बाह्र | bāhr | /barʱ/ | |

| 20 | २० | बीस | vis | /bis/ | |

| 21 | २१ | एक्काइस | ekkāis | /ekkais/ | |

| 22 | २२ | बाइस | bāis | /bais/ | |

| 100 | १०० | एक सय | ek say | /ek sʌi/ | |

| 1 000 | १००० | एक हजार | ek hajār | /ek ɦʌd͡zar/ | |

| 10 000 | १०००० | दश हजार | daś hajār | /d̪ʌs ɦʌd͡zar/ | |

| 100 000 | १००००० | एक लाख | ek lākh | /ek lakʰ/ | See lakh |

| 1 000 000 | १०००००० | दश लाख | daś lākh | /d̪ʌs lakʰ/ | |

| 10 000 000 | १००००००० | एक करोड | ek karoḍ | /ek kʌroɽ/ | See crore |

Greetings

| English | Nepali | Transliteration |

|---|---|---|

| Hello (informal/to someone of older age) | नमस्ते / नमस्कार | namaste / namaskār |

| Nice to meet you | तपाईंलाई भेटेर खुशी लाग्याे | tapāī lāī bheṭera khuśī lāgyo |

| How are you? | तपाईँलाई कस्तो छ ? | tapāī lāī kasto chha? |

| My name is Bryan Butler. | मेराे नाम ब्रायन बट्लर हाे । | mero nām brayan batlar ho |

| I am from America. | म अमेरिकाबाट हुँ । | ma amerikābāṭ hung |

| Good morning to all of you | सबैजनालाई शुभ-प्रभात । | sabejanālāī shubh-prabhāt |

| Goodnight | शुभ-रात्री | shubh-ratrī |

| Day | दिन । | din |

| Evening | साँझ | sāṃjh |

| I am feeling thirsty. | म तिर्खाएकाे छु । | ma tirkhāeko chu |

| I am feeling hungry. | म भाेकाएकाे छु । | ma bhokāeko chu |

| Tasty | मिठो / स्वादिलो | mitho / swadilo |

| I am sorry. (formal) | म क्षमा प्रार्थी छु । | ma kṣamā prarthi chu |

| Where is the place to bath? | नुहाउने ठाउँ कहाँ छ ? | nuhāune ṭhāu kahā cha |

| Thank you | धन्यवाद | Dhanyavād |

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 Richard Burghart 1984, pp. 118-119.

- ↑ Nepali at Ethnologue (19th ed., 2016)

Nepali at Ethnologue (19th ed., 2016)

Doteli at Ethnologue (19th ed., 2016) - ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Nepali [1]". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Nepali [2]". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ Language Gulper: Languages and Ethnic Groups of Bhutan (2014).

- ↑ "Official Nepali language in Sikkim & Darjeeling" (PDF). CensusIndia.gov.in.

- ↑ Hodgson, Brian Houghton (2013). Essays on the Languages, Literature, and Religion of Nepál and Tibet (Reprint ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 2. ISBN 9781108056083. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- ↑ The origin of Nepali language is Sinja of Jumla. Therefore, the Nepali dialect “Khas Bhasa” is still spoken among the people in this region., retrieved Feb 25, 2018

- ↑ "Major highlights" (PDF). Central Bureau of Statistics. 2013. p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 July 2013. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- 1 2 "Nepali (npi)". Ethnologue. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- ↑ Gurung, Dr. Harka (19–20 January 2005). "Social Exclusion and Maoist Insurgency". Retrieved 13 April 2012. Page 5.

- 1 2 "Background Note: Bhutan". U.S. Department of State. 2010-02-02. Retrieved 2010-10-02.

- ↑ Worden, Robert L.; Savada, Andrea Matles (ed.) (1991). "Chapter 6: Bhutan - Ethnic Groups". Nepal and Bhutan: Country Studies (3rd ed.). Federal Research Division, United States Library of Congress. p. 424. ISBN 0-8444-0777-1. Retrieved 2010-10-02.

- ↑ "Census of India". Archived from the original on 13 May 2010. Retrieved 2008-01-07.

- ↑ Balfour, Edward (1871). Cyclopædia of India and of Eastern and Southern Asia, Commercial, Industrial and Scientific: Products of the Mineral, Vegetable and Animal Kingdoms, Useful Arts and Manufactures. Printed at the Scottish & Adelphi presses. p. 529.

- ↑ Cust, Robert N. (1878). A Sketch of the Modern Languages of the East Indies. Routledge. p. 51. ISBN 9781136384691.

- ↑ Richard Burghart 1984, p. 118.

- ↑ General, India Office of the Registrar (1967). Census of India, 1961: Tripura. Manager of Publications. p. 336.

Nepali (Naipali in 1951)

- ↑ Commissioner, India Census; Gait, Edward Albert (1902). Census of India, 1901. Office of the Superintendent of Government Printing, India. p. 91.

Naipali is an Indo-Aryan language spoken by the upper classes in Nepal, whereas the minor Nepalese languages, such as Gurung, Magar, Jimdar, Yakha, etc., are members of the Tibeto-Burman family;

- ↑ Onta, Pratyoush (1996) "Creating a Brave Nepali Nation in British India: The Rhetoric of Jati Improvement, Rediscovery of Bhanubhakta and the Writing of Bir History" in Studies in Nepali History and Society 1(1), p. 37-76.

- ↑ "Languages of Nepal".

- ↑ "Nepal". Ethnologue. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- ↑ "Nepali (nep)". Ethnologue. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

Bibliography

Further reading

- पोखरेल, मा. प्र. (2000), ध्वनिविज्ञान र नेपाली भाषाको ध्वनि परिचय, नेपाल राजकीय प्रज्ञा प्रतिष्ठान, काठमाडौँ।

- Schmidt, R. L. (1993) A Practical Dictionary of Modern Nepali.

- Turner, R. L. (1931) A Comparative and Etymological Dictionary of the Nepali Language.

- Clements, G.N. & Khatiwada, R. (2007). “Phonetic realization of contrastively aspirated affricates in Nepali.” In Proceedings of ICPhS XVI (Saarbrücken, 6–10 August 2007), 629- 632.

- Hutt, M. & Subedi, A. (2003) Teach Yourself Nepali.

- Khatiwada, R. (2009) ‘Nepali’, Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 39(3), pp. 373–380. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025100309990181

- Manders, C. J. (2007) नेपाली व्याकरणमा आधार A Foundation in Nepali Grammar.

- Dr. Dashrath Kharel, "Nepali linguistics spoken in Darjeeling-Sikkim"

External links

| Nepali edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

- Omniglot - Nepali Language

- Ayton, J. A. (1820). A Grammar of the Népalese Language. Calcutta: Hindoostanee Press.