Bollywood

| Hindi cinema (Bollywood) | |

|---|---|

.svg.png) | |

| Main distributors |

Eros International Reliance Big Pictures UTV Motion Pictures Yash Raj Films[1][2] |

| Produced feature films (2017)[3] | |

| Total | 364 |

| Gross box office | |

| Total | ₹15,500 crore (US$2.2 billion) (2016)[4] |

| National films | India: ₹3,500 crore (US$565 million) (2014)[5] |

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of India |

|---|

|

| History |

| People |

|

Mythology and folklore |

| Cuisine |

| Religion |

|

Music and performing arts |

| Sport |

|

|

Hindi cinema, often metonymously referred to as Bollywood, is the Indian Hindi-language film industry, based in the city of Mumbai (formerly Bombay), Maharashtra, India. The term being a portmanteau of "Bombay" and "Hollywood", Bollywood is a part of the larger cinema of India (also known as Indywood),[6] which includes other production centers producing films in other Indian languages.[7][8] Linguistically, Bollywood films tend to use a colloquial dialect of Hindi-Urdu, or Hindustani, mutually intelligible to both Hindi and Urdu speakers,[9][10][11] while modern Bollywood films also increasingly incorporate elements of Hinglish.[9]

Indian cinema is the world's largest film industry in terms of film production, with an annual output of 1,986 feature films as of 2017, and Bollywood is its largest film producer, with 364 Hindi films produced annually as of 2017.[3] Bollywood represents 43% of Indian net box office revenue, while Tamil and Telugu cinema represent 36%, and the rest of the regional cinema constitute 21%, as of 2014.[5] Bollywood is thus one of the largest centers of film production in the world.[12][13][14] According to certain news outlets, in terms of ticket sales in 2001, Indian cinema sold an estimated 3.6 billion tickets annually across the globe, compared to Hollywood's 2.6 billion tickets sold.[15][16][17]

Etymology

The name "Bollywood" is a portmanteau derived from Bombay (the former name for Mumbai) and Hollywood (in California), the center of the American film industry.[18] The naming scheme for "Bollywood" was inspired by "Tollywood", the name that was used to refer to the cinema of West Bengal. Dating back to 1932, "Tollywood" was the earliest Hollywood-inspired name, referring to the Bengali film industry based in Tollygunge (in Calcutta, West Bengal), whose name is reminiscent of "Hollywood" and was the centre of the cinema of India at the time.[19] It was this "chance juxtaposition of two pairs of rhyming syllables," Holly and Tolly, that led to the portmanteau name "Tollywood" being coined. The name "Tollywood" went on to be used as a nickname for the Bengali film industry by the popular Calcutta-based Junior Statesman youth magazine, establishing a precedent for other film industries to use similar-sounding names, eventually leading to the coining of "Bollywood".[20] "Tollywood" is now also popularly used to refer to the Telugu film industry in Telangana and Andhra Pradesh.

The term "Bollywood" itself has origins in the 1970s, when India overtook the United States as the world's largest film producer. Credit for the term has been claimed by several different people, including the lyricist, filmmaker and scholar Amit Khanna,[21] and the journalist Bevinda Collaco.[22] Bollywood does not exist as a physical place. Some deplore the name, arguing that it makes the industry look like a poor cousin to Hollywood.[18][23]

History

Early history (1910s–1940s)

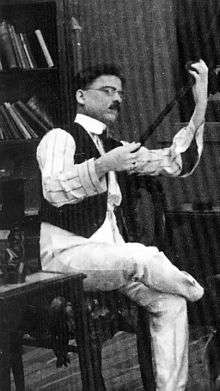

Raja Harishchandra (1913), by Dadasaheb Phalke, is known as the first silent feature film made in India. By the 1930s, the industry was producing over 200 films per annum.[27] The first Indian sound film, Ardeshir Irani's Alam Ara (1931), was a major commercial success.[28] There was clearly a huge market for talkies and musicals; Bollywood and all the regional film industries quickly switched to sound filming.

The 1930s and 1940s were tumultuous times: India was buffeted by the Great Depression, World War II, the Indian independence movement, and the violence of the Partition. Most Bollywood films were unabashedly escapist, but there were also a number of filmmakers who tackled tough social issues, or used the struggle for Indian independence as a backdrop for their plots.[27]

In 1937, Ardeshir Irani, of Alam Ara fame, made the first colour film in Hindi, Kisan Kanya. The next year, he made another colour film, a version of Mother India. However, colour did not become a popular feature until the late 1950s. At this time, lavish romantic musicals and melodramas were the staple fare at the cinema.

Prior to the 1947 partition of India, which was divided into the Republic of India and Pakistan, the Bombay film industry (now called Bollywood) was closely to the Lahore film industry (now the Lollywood industry of Pakistani cinema), as both produced films in Hindi-Urdu, or Hindustani, the lingua franca across northern and central India. In the 1940s, many actors, filmmakers and musicians in the Lahore industry migrated to the Bombay industry, including actors such as K.L. Saigal, Prithviraj Kapoor, Dilip Kumar and Dev Anand and singers such as Mohammed Rafi, Noorjahan and Shamshad Begum. Around that time, filmmakers and actors from the Bengali film industry based in Calcutta (now Kolkata) also began migrating to the Bombay film industry, which for decades after partition would be dominated by actors, filmmakers and musicians with origins in what is today Pakistani Punjab, along with those from Bengal.[29]

Golden Age (late 1940s–1960s)

Following India's independence, the period from the late 1940s to the early 1960s is regarded by film historians as the "Golden Age" of Hindi cinema.[30][31][32] Some of the most critically acclaimed Hindi films of all time were produced during this period. Examples include Pyaasa (1957) and Kaagaz Ke Phool (1959) directed by Guru Dutt and written by Abrar Alvi, Awaara (1951) and Shree 420 (1955) directed by Raj Kapoor and written by Khwaja Ahmad Abbas, and Aan (1952) directed by Mehboob Khan and starring Dilip Kumar. These films expressed social themes mainly dealing with working-class life in India, particularly urban life in the former two examples; Awaara presented the city as both a nightmare and a dream, while Pyaasa critiqued the unreality of city life.[33]

Mehboob Khan's Mother India (1957), a remake of his earlier Aurat (1940), was the first Indian film to be nominated for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film, which it lost by a single vote.[34] Mother India was also an important film that defined the conventions of Hindi cinema for decades.[35][36][37] It spawned a new genre of dacoit films, which was further defined by Gunga Jumna (1961).[38] Written and produced by Dilip Kumar, Gunga Jumna was a dacoit crime drama about two brothers on opposite sides of the law, a theme that later became common in Indian films since the 1970s.[39] Madhumati (1958), directed by Bimal Roy and written by Ritwik Ghatak, popularised the theme of reincarnation in Western popular culture.[40] Some of the most famous epic films of Hindi cinema were also produced at the time, such as K. Asif's Mughal-e-Azam (1960).[41] Other acclaimed mainstream Hindi filmmakers at the time included Kamal Amrohi and Vijay Bhatt.

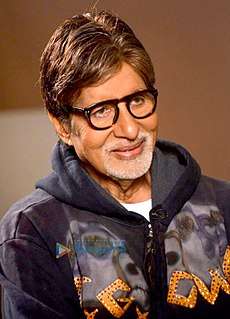

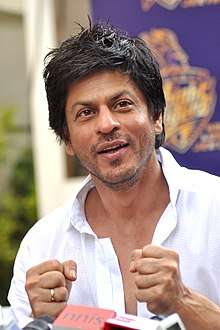

Successful actors at the time included Dilip Kumar, Pradeep Kumar, Raj Kapoor, Dev Anand, and Guru Dutt, while successful actresses included Suraiya, Nargis, Sumitra Devi, Madhubala, Meena Kumari, Waheeda Rehman, Nutan, Sadhana, Mala Sinha and Vyjayanthimala.[45] The three most popular male Indian actors of the 1950s and 1960s were Dilip Kumar, Raj Kapoor, and Dev Anand, each with their own unique acting style. Kapoor followed the "tramp" style of Charlie Chaplin, Anand modelled himself after the "suave" style of Hollywood movie stars like Gregory Peck and Cary Grant, and Kumar pioneered a form of method acting that was similar to yet predated Hollywood method actors such as Marlon Brando. Kumar, who was described as "the ultimate method actor" by Satyajit Ray and is considered one of India's greatest actors, inspired future generations of Indian actors; much like Brando's influence on Robert De Niro and Al Pacino, Kumar had a similar influence on later Indian actors such as Amitabh Bachchan, Naseeruddin Shah, Shah Rukh Khan and Nawazuddin Siddiqui.[42][43]

While commercial Hindi cinema was thriving, the 1950s also saw the emergence of a new Parallel Cinema movement.[33] Though the movement was mainly led by Bengali cinema, it also began gaining prominence in Hindi cinema. The movement emphasized social realism. Early examples of films in this movement include Dharti Ke Lal (1946) directed by Khwaja Ahmad Abbas and based on the Bengal famine of 1943,[46] Neecha Nagar (1946) directed by Chetan Anand and written by Khwaja Ahmad Abbas,[47] and Bimal Roy's Do Bigha Zamin (1953). Their critical acclaim, as well as the latter's commercial success, paved the way for Indian neorealism[48] and the Indian New Wave.[49] Some of the internationally acclaimed Hindi filmmakers involved in the movement included Mani Kaul, Kumar Shahani, Ketan Mehta, Govind Nihalani, Shyam Benegal and Vijaya Mehta.[33]

Ever since the social realist film Neecha Nagar won the Grand Prize at the first Cannes Film Festival,[47] Hindi films were frequently in competition for the Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival throughout the 1950s and early 1960s, with some of them winning major prizes at the festival.[50] Guru Dutt, while overlooked in his own lifetime, had belatedly generated international recognition much later in the 1980s.[50][51] Dutt is now regarded as one of the greatest Asian filmmakers of all time, alongside the more famous Indian Bengali filmmaker Satyajit Ray. The 2002 Sight & Sound critics' and directors' poll of greatest filmmakers ranked Dutt at No. 73 on the list.[52] Some of his films are now included among the greatest films of all time, with Pyaasa (1957) being featured in Time magazine's "All-TIME" 100 best movies list,[53] and with both Pyaasa and Kaagaz Ke Phool (1959) tied at No. 160 in the 2002 Sight & Sound critics' and directors' poll of all-time greatest films. Several other Hindi films from this era were also ranked in the Sight & Sound poll, including Raj Kapoor's Awaara (1951), Vijay Bhatt's Baiju Bawra (1952), Mehboob Khan's Mother India (1957) and K. Asif's Mughal-e-Azam (1960) all tied at No. 346 on the list.[54]

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Dharmendra became successful with action films. Later the industry was dominated by musical romance films with "romantic hero" leads, the most popular being Rajesh Khanna.[55] Other actors during this period include Shammi Kapoor, Jeetendra, Sanjeev Kumar, and Shashi Kapoor, and actresses like Sharmila Tagore, Mumtaz, Saira Banu, Helen and Asha Parekh.

Classic Bollywood (1970s–1980s)

By the start of the 1970s, Hindi cinema was experiencing thematic stagnation,[58] dominated by musical romance films.[55] The arrival of screenwriter duo Salim-Javed, consisting of Salim Khan and Javed Akhtar, marked a paradigm shift, revitalizing the industry.[58] They began the genre of gritty, violent, Bombay underworld crime films in the early 1970s, with films such as Zanjeer (1973) and Deewaar (1975).[59][60] They reinterpreted the rural themes of Mehboob Khan's Mother India (1957) and Dilip Kumar's Gunga Jumna (1961) in a contemporary urban context reflecting the socio-economic and socio-political climate of 1970s India,[58][61] channeling the growing discontent and disillusionment among the masses,[58] and unprecedented growth of slums,[62] and dealing with themes involving urban poverty, corruption, and crime,[63] as well as anti-establishment themes.[64] This resulted in their creation of the "angry young man", personified by Amitabh Bachchan,[64] who reinterpreted Dilip Kumar's performance in Gunga Jumna in a contemporary urban context,[58][61] and giving a voice to the angst of the urban poor.[62]

By the mid-1970s, romantic confections had made way for gritty, violent crime films and action films about gangsters (Bombay underworld) and bandits (dacoits). The writing of Salim-Javed and acting of Amitabh Bachchan popularized the trend, with films such as Zanjeer and particularly Deewaar, a crime film inspired by Gunga Jumna[39] that pitted "a policeman against his brother, a gang leader based on real-life smuggler Haji Mastan" portrayed by Bachchan; Deewaar was described as being "absolutely key to Indian cinema" by Danny Boyle.[70] Along with Bachchan, other actors that rode the crest of this trend include Feroz Khan,[71] Mithun Chakraborty, Naseeruddin Shah, Jackie Shroff, Sanjay Dutt, Anil Kapoor and Sunny Deol, which lasted into the early 1990s. Actresses from this era included Hema Malini, Jaya Bachchan, Raakhee, Shabana Azmi, Zeenat Aman, Parveen Babi, Rekha, Dimple Kapadia, Smita Patil, Jaya Prada and Padmini Kolhapure.[45]

The 1970s was also when the name "Bollywood" was coined,[22][21] and when the quintessential conventions of commercial Bollywood films were established.[72] Key to this was the emergence of the masala film genre, which combines elements of multiple genres (action, comedy, romance, drama, melodrama, musical). The masala film was pioneered in the early 1970s by filmmaker Nasir Hussain,[73] along with screenwriter duo Salim-Javed,[72] pioneering the Bollywood blockbuster format.[72] Yaadon Ki Baarat (1973), directed by Hussain and written by Salim-Javed, has been identified as the first masala film and the "first" quintessentially "Bollywood" film.[74][72] Salim-Javed went on to write more successful masala films in the 1970s and 1980s.[72] Masala films launched Amitabh Bachchan into the biggest Bollywood movie star of the 1970s and 1980s. A landmark for the masala film genre was Amar Akbar Anthony (1977),[75][74] directed by Manmohan Desai and written by Kader Khan. Manmohan Desai went on to successfully exploit the genre in the 1970s and 1980s.

Both these trends, the masala film and the violent crime film, are represented by the blockbuster Sholay (1975), written by Salim-Javed and starring Amitabh Bachchan. It combined the dacoit film conventions of Mother India and Gunga Jumna with that of Spaghetti Westerns, spawning the Dacoit Western genre (also known as the "Curry Western"), which was popular in the 1970s.[38]

Some Hindi filmmakers such as Shyam Benegal continued to produce realistic Parallel Cinema throughout the 1970s,[76] alongside Mani Kaul, Kumar Shahani, Ketan Mehta, Govind Nihalani and Vijaya Mehta.[33] However, the 'art film' bent of the Film Finance Corporation came under criticism during a Committee on Public Undertakings investigation in 1976, which accused the body of not doing enough to encourage commercial cinema. The 1970s thus saw the rise of commercial cinema in the form of enduring films such as Sholay (1975), which consolidated Amitabh Bachchan's position as a lead actor. The devotional classic Jai Santoshi Ma was also released in 1975.[77]

The most internationally acclaimed Hindi film of the 1980s was Mira Nair's Salaam Bombay! (1988), which won the Camera d'Or at the 1988 Cannes Film Festival and was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film.

New Bollywood (1990s–present)

In the late 1980s, Hindi cinema experienced another period of stagnation, with a decline in box office turnout, due to increasing violence, decline in musical melodic quality, and rise in video piracy, leading to middle-class family audiences abandoning theaters. The turning point came with Qayamat Se Qayamat Tak (1988), directed by Mansoor Khan, written and produced by his father Nasir Hussain, and starring his cousin Aamir Khan with Juhi Chawla. Its blend of youthfulness, wholesome entertainment, emotional quotients and strong melodies lured family audiences back to the big screen.[79][80] It set a new template for Bollywood musical romance films that defined Hindi cinema in the 1990s.[80]

The period of Hindi cinema from the 1990s onwards is referred to as "New Bollywood" cinema,[81] linked to economic liberalisation in India during the early 1990s.[82] By the early 1990s, the pendulum had swung back toward family-centric romantic musicals. Qayamat Se Qayamat Tak was followed by blockbusters such as Maine Pyar Kiya (1989), Chandni (1989), Hum Aapke Hain Kaun (1994), Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge (1995), Raja Hindustani (1996), Dil To Pagal Hai (1997), Pyaar To Hona Hi Tha (1998) and Kuch Kuch Hota Hai (1998). A new generation of popular actors emerged, such as Aamir Khan, Aditya Pancholi, Ajay Devgan, Akshay Kumar, Salman Khan (Salim Khan's son), and Shahrukh Khan, and actresses such as Madhuri Dixit, Sridevi, Juhi Chawla, Meenakshi Seshadri, Manisha Koirala, Kajol, and Karisma Kapoor.[45] In that point of time, action films and comedy films were also successful, with actors like Govinda, Sunny Deol, Sunil Shetty, Akshay Kumar, and Ajay Devgan, with Akshay Kumar gaining popularity for performing dangerous stunts in action films in his well-known Khiladi (film series) and other action films.[83][84] Other actresses during this time included Raveena Tandon, Twinkle Khanna, Sonali Bendre, Sushmita Sen, Mahima Chaudhary and Shilpa Shetty.

This decade also marked the entry of new performers in arthouse and independent films, some of which succeeded commercially, the most influential example being Satya (1998), directed by Ram Gopal Varma and written by Anurag Kashyap. The critical and commercial success of Satya led to the emergence of a distinct genre known as Mumbai noir,[85] urban films reflecting social problems in the city of Mumbai.[86] This led to a resurgence of Parallel Cinema by the end of the decade.[85] These films often featured actors like Nana Patekar and Manoj Bajpai, and actresses like Manisha Koirala, Tabu, Pooja Bhatt and Urmila Matondkar, whose performances were usually critically acclaimed.

.jpg)

Since the 1990s, the three biggest Bollywood movie stars have been the "Three Khans": Aamir Khan, Shah Rukh Khan, and Salman Khan.[87][88] Combined, they have starred in the top ten highest-grossing Bollywood films. The three Khans have had successful careers since the late 1980s,[87] and have dominated the Indian box office since the 1990s,[89] across three decades.[90] Shah Rukh Khan was the most successful Indian actor for most of the 1990s and 2000s, while Aamir Khan has been the most successful Indian actor since the late 2000s;[78] according to Forbes, Aamir Khan is "arguably the world's biggest movie star" as of 2017, due to his immense popularity in the world's two most populous nations, India and China.[91]

The 2000s saw a growth in Bollywood's recognition across the world due to a growing and prospering NRI and Desi communities overseas. A fast growth in the Indian economy and a demand for quality entertainment in this era, led the nation's film-making to new heights in terms of production values, cinematography and innovative story lines as well as technical advances in areas such as special effects and animation.[96] Some of the largest production houses, among them Yash Raj Films and Dharma Productions were the producers of new modern films.[96] Some popular films of the decade were Kaho Naa... Pyaar Hai (2000), Gadar: Ek Prem Katha (2001), Lagaan (2001), Koi... Mil Gaya (2003), Munna Bhai M.B.B.S. (2003), Rang De Basanti (2006), Lage Raho Munna Bhai (2006), Dhoom 2 (2006), Krrish (2006) and Jab We Met (2007) among others. This decade also saw the rise of popular actors and movie stars like Arjun Rampal, Hrithik Roshan, Abhishek Bachchan, Vivek Oberoi, Shahid Kapoor and John Abraham, as well as actresses like Aishwarya Rai, Rani Mukerji, Preity Zinta, Ameesha Patel, Lara Dutta, Bipasha Basu, Kareena Kapoor, Priyanka Chopra and Katrina Kaif.

In the 2010s, the industry saw the trend of established movie stars like Salman Khan, Akshay Kumar and Shahrukh Khan making big-budget masala entertainers like Dabangg (2010), Ek Tha Tiger (2012), Rowdy Rathore (2012), Chennai Express (2013), Kick (2014) and Happy New Year (2014) opposite much younger actresses. These films were often not the subject of critical acclaim, but were nonetheless major commercial successes. On the other hand, Aamir Khan has been credited for redefining and modernizing the masala film (which originated from his uncle Nasir Hussain's Yaadon Ki Baarat, which he first appeared in) with his own distinct brand of socially conscious cinema in the early 21st century.[97] His films blur the distinction between commercial masala films and realistic parallel cinema, combining the entertainment and production values of the former with the believable narratives and strong messages of the latter, earning both commercial success and critical acclaim, in India and overseas.[98]

While most stars from the 2000s continued their successful careers into the next decade, the 2010s also saw the rise of a new generation of popular actors like Ranbir Kapoor, Ranveer Singh, Varun Dhawan, Sidharth Malhotra, Sushant Singh Rajput, Arjun Kapoor, Aditya Roy Kapur and Tiger Shroff, as well as actresses like Vidya Balan, Kangana Ranaut, Deepika Padukone, Sonam Kapoor, Anushka Sharma, Sonakshi Sinha, Jacqueline Fernandez, Shraddha Kapoor and Alia Bhatt, with Balan and Ranaut gaining wide recognition for successful female-centric films such as The Dirty Picture (2011), Kahaani (2012) and Queen (2014), and Tanu Weds Manu Returns (2015). Kareena Kapoor and Bipasha Basu are among the few working actresses from the 2000s who successfully completed 15 years in the industry.

Influences for Bollywood

Moti Gokulsing and Wimal Dissanayake identify six major influences that have shaped the conventions of Indian popular cinema:[99]

- The ancient Indian epics of Mahabharata and Ramayana which have exerted a profound influence on the thought and imagination of Indian popular cinema, particularly in its narratives. Examples of this influence include the techniques of a side story, back-story and story within a story. Indian popular films often have plots which branch off into sub-plots; such narrative dispersals can clearly be seen in the 1993 films Khalnayak and Gardish.[99]

- Ancient Sanskrit drama, with its highly stylised nature and emphasis on spectacle, where music, dance and gesture combined "to create a vibrant artistic unit with dance and mime being central to the dramatic experience." Sanskrit dramas were known as natya, derived from the root word nrit (dance), characterising them as spectacular dance-dramas which has continued Indian cinema.[99] The theory of rasa dating back to ancient Sanskrit drama is believed to be one of the most fundamental features that differentiate Indian cinema, particularly Hindi cinema, from that of the Western world.[100]

- The traditional folk theatre of India, which became popular from around the 10th century with the decline of Sanskrit theatre. These regional traditions include the Jatra of Bengal, the Ramlila of Uttar Pradesh, and the Terukkuttu of Tamil Nadu.[99]

- The Parsi theatre, which "blended realism and fantasy, music and dance, narrative and spectacle, earthy dialogue and ingenuity of stage presentation, integrating them into a dramatic discourse of melodrama. The Parsi plays contained crude humour, melodious songs and music, sensationalism and dazzling stagecraft."[99]

- Hollywood, where musicals were popular from the 1920s to the 1950s, though Indian filmmakers departed from their Hollywood counterparts in several ways. "For example, the Hollywood musicals had as their plot the world of entertainment itself. Indian filmmakers, while enhancing the elements of fantasy so pervasive in Indian popular films, used song and music as a natural mode of articulation in a given situation in their films. There is a strong Indian tradition of narrating mythology, history, fairy stories and so on through song and dance." In addition, "whereas Hollywood filmmakers strove to conceal the constructed nature of their work so that the realistic narrative was wholly dominant, Indian filmmakers made no attempt to conceal the fact that what was shown on the screen was a creation, an illusion, a fiction. However, they demonstrated how this creation intersected with people's day to day lives in complex and interesting ways."[99]

- Western musical television, particularly MTV, which has had an increasing influence since the 1990s, as can be seen in the pace, camera angles, dance sequences and music of 2000s Indian films. An early example of this approach was in Mani Ratnam's Bombay (1995).[99]

Sharmistha Gooptu and Bhaumik identify Indo-Persian/Islamicate culture as a major influence. In the early 20th century, Urdu was the lingua franca of popular cultural performances across northern India, established in popular performance art traditions such as nautch dancing, Urdu poetry, and Parsi theater. Urdu and related Hindi dialects were the most widely understood across northern India, thus Hindi-Urdu became the standardized language of early Indian talkies. The One Thousand and One Nights (Arabian Nights) also had a strong influence, on Parsi theater which performed "Persianate adventure-romances" that were adapted into films, and on early Bombay cinema where "Arabian Nights cinema" was a popular genre.[101]

The scholars Chaudhuri Diptakirti and Rachel Dwyer, and the screenwriter Javed Akhtar, identify Urdu literature as a major influence on Hindi cinema.[102][103][104][10] Most of the screenwriters and scriptwriters of classic Hindi cinema often came from Urdu literary backgrounds,[104][102][10] from Khwaja Ahmad Abbas and Akhtar ul Iman to Salim-Javed and Rahi Masoom Raza, while a handful of screenwriters and scriptwriters also came from other Indian literary traditions such as Bengali literature and Hindi literature.[102] Most of Hindi cinema's classic scriptwriters wrote their scripts and dialogues mainly in Urdu, including the likes of Salim-Javed, Gulzar, Rajinder Singh Bedi, Inder Raj Anand, Rahi Masoom Raza and Wajahat Mirza.[10] Urdu poetry strongly influenced filmi Bollywood songs,[103][10] where the lyrics draw heavily from Urdu poetry and the ghazal tradition.[103]

Todd Stadtman identifies several foreign influences on commercial Bollywood masala films in the 1970s, including New Hollywood, Italian exploitation films, and Hong Kong martial arts cinema.[71] Starting with Deewaar (1975), Bollywood films up until the 1990s often incorporated fight sequences inspired by 1970s martial arts films from Hong Kong cinema.[105] Rather than following the Hollywood model, Bollywood action scenes tended to follow the Hong Kong model, with an emphasis on acrobatics and stunts, and combining kung fu (as it was perceived by Indians) with Indian martial arts (particularly Indian wrestling).[106]

Influence of Bollywood

India

Perhaps the biggest influence of Bollywood has been on nationalism in India itself, where along with rest of Indian cinema, it has become part and parcel of the 'Indian story'.[107] In India, Bollywood is often associated with India's national identity.[15] In the words of the economist and Bollywood biographer Lord Meghnad Desai,[107]

Cinema actually has been the most vibrant medium for telling India its own story, the story of its struggle for independence, its constant struggle to achieve national integration and to emerge as a global presence.

Bollywood has influenced Indian society and culture for a long time. For many decades, Bollywood has influenced daily life and culture in India, where it has been the biggest entertainment industry. Many of the musical, dancing, wedding and fashion trends in India, for example, have been influenced by Bollywood. Some of the biggest Bollywood fashion trendsetters have included Madhubala in Mughal-e-Azam (1960) and Madhuri Dixit in Hum Aapke Hain Koun..! (1994).[87]

Bollywood has also had a socio-political impact on Indian society, reflecting Indian politics over the decades.[108] In classic Bollywood cinema of the 1970s, for example, popular Bombay underworld crime films written by Salim-Javed and starring Amitabh Bachchan, such as Zanjeer (1973) and Deewaar (1975), reflected the socio-economic and socio-political realities of 1970s India, channeling the growing popular discontent and disillusionment among the masses, and the failure of the state in ensuring their welfare and well-being, in a time when prices were rapidly rising, commodities were becoming scarce, public institutions were losing legitimacy, smugglers and gangsters were gathering political clout,[58] and there was an unprecedented growth of slums.[62] The cinema of Salim-Javed and Amitabh Bachchan dealt with themes relevant to Indian society at the time, such as urban poverty in slums, corruption in society, and the Bombay underworld crime scene,[63] and was perceived by audiences as anti-establishment, often represented by an "angry young man" protagonist, presented as a vigilante or anti-hero,[64] with his suppressed rage giving a voice to the angst of the urban poor.[62]

Overseas

Overseas, Bollywood has been a prominent form of soft power for India, increasing India's influence overseas, as well as changing overseas perceptions of India.[109][110] In Western European countries such as Germany, for example, stereotypes of the country included bullock carts, beggars, sacred cows, corrupt politicians, and catastrophes, before Bollywood as well as the IT industry transformed global perceptions of India.[111] According to author Roopa Swaminathan, "Bollywood cinema is one of the strongest global cultural ambassadors of a new India."[110][112] The role of Bollywood in exerting India's global influence is comparable to the role of Hollywood in exerting America's global influence.[87] See Global markets below for further information on Bollywood's influence in different global regions.

Bollywood has also influenced Hollywood and other film industries.[15] In the 2000s, Bollywood began influencing musical films in the Western world, and played a particularly instrumental role in the revival of the American musical film genre. Baz Luhrmann stated that his musical film Moulin Rouge! (2001) was directly inspired by Bollywood musicals.[113] The film incorporated an Indian-themed play based on the ancient Sanskrit drama Mṛcchakatika and a Bollywood-style dance sequence with a song from the film China Gate (1998). The critical and financial success of Moulin Rouge! renewed interest in the then-moribund Western musical genre, and subsequently films such as Chicago, The Producers, Rent, Dreamgirls, Hairspray, Sweeney Todd, Across the Universe, The Phantom of the Opera, Enchanted and Mamma Mia! were produced, fuelling a renaissance of the genre.[114][115]

A. R. Rahman, an Indian film composer, wrote the music for Andrew Lloyd Webber's Bombay Dreams, and a musical version of Hum Aapke Hain Koun has played in London's West End. The Bollywood sports film Lagaan (2001) was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film, and two other Bollywood films Devdas (2002) and Rang De Basanti (2006) were nominated for the BAFTA Award for Best Film Not in the English Language.

Danny Boyle's Slumdog Millionaire (2008), which won four Golden Globes and eight Academy Awards, was directly inspired by Bollywood films,[70][116] and is considered to be a "homage to Hindi commercial cinema",[117] inspired by Mumbai underworld crime films such as Deewaar (1975), Satya (1998), Company (2002) and Black Friday (2007).[70] Deewaar also had a Hong Kong remake, The Brothers (1979),[118] which went on to inspire John Woo's internationally acclaimed breakthrough A Better Tomorrow (1986),[119][118] which set the template for the heroic bloodshed genre in Hong Kong action cinema.[120][121] 1970s "angry young man" epics such as Deewaar and Amar Akbar Anthony (1977) have similarities to the heroic bloodshed genre of 1980s Hong Kong action cinema.[122] The theme of reincarnation was popularised in Western popular culture through Bollywood films, with Madhumati (1958) inspiring the Hollywood film The Reincarnation of Peter Proud (1975),[40] which in turn inspired the Bollywood film Karz (1980), which in turn influenced another Hollywood film Chances Are (1989).[123] The 1975 film Chhoti Si Baat is believed to have inspired Hitch (2005), which in turn inspired the Bollywood film Partner (2007).[124]

The influence of filmi Bollywood music can also be seen in popular music elsewhere in the world. In 1978, technopop pioneers Haruomi Hosono and Ryuichi Sakamoto of the Yellow Magic Orchestra produced an electronic album Cochin Moon based on an experimental fusion between electronic music and Bollywood-inspired Indian music.[125] Devo's 1988 hit song "Disco Dancer" was inspired by the song "I am a Disco Dancer" from the Bollywood film Disco Dancer (1982).[126] The 2002 song "Addictive", sung by Truth Hurts and produced by DJ Quik and Dr. Dre, was lifted from Lata Mangeshkar's "Thoda Resham Lagta Hai" from Jyoti (1981).[127] The Black Eyed Peas' Grammy Award winning 2005 song "Don't Phunk with My Heart" was inspired by two 1970s Bollywood songs: "Ye Mera Dil Yaar Ka Diwana" from Don (1978) and "Ae Nujawan Hai Sub" from Apradh (1972).[128] Both songs were originally composed by Kalyanji Anandji, sung by Asha Bhosle, and featured the dancer Helen.[129]

In 2005, the Kronos Quartet re-recorded several R. D. Burman compositions, with Asha Bhosle as the singer, into an album You've Stolen My Heart: Songs from R.D. Burman's Bollywood, which was nominated for "Best Contemporary World Music Album" at the 2006 Grammy Awards. Filmi music composed by A. R. Rahman (who would later win two Academy Awards for the Slumdog Millionaire soundtrack) has frequently been sampled by musicians elsewhere in the world, including the Singaporean artist Kelly Poon, the Uzbek artist Iroda Dilroz, the French rap group La Caution, the American artist Ciara, and the German band Löwenherz,[130] among others. Many Asian Underground artists, particularly those among the overseas Indian diaspora, have also been inspired by Bollywood music.

Genre conventions

Bollywood films are mostly musicals and are expected to contain catchy music in the form of song-and-dance numbers woven into the script. A film's success often depends on the quality of such musical numbers.[131] Indeed, a film's music is often released before the movie and helps increase the audience.

Indian audiences expect full value for their money, with a good entertainer generally referred to as paisa vasool, (literally, "money's worth").[132] Songs and dances, love triangles, comedy and dare-devil thrills are all mixed up in a three-hour extravaganza with an intermission. They are called Masala films, after the Hindi word for a spice mixture. Like masalas, these movies are a mixture of many things such as action, comedy, romance and so on. Most films have heroes who are able to fight off villains all by themselves.

Bollywood plots have tended to be melodramatic. They frequently employ formulaic ingredients such as star-crossed lovers and angry parents, love triangles, family ties, sacrifice, corrupt politicians, kidnappers, conniving villains, courtesans with hearts of gold, long-lost relatives and siblings separated by fate, dramatic reversals of fortune, and convenient coincidences.

There have always been Indian films with more artistic aims and more sophisticated stories, both inside and outside the Bollywood tradition (see Parallel Cinema). They often lost out at the box office to movies with more mass appeal. Bollywood conventions are changing, however. A large Indian diaspora in English-speaking countries, and increased Western influence at home, have nudged Bollywood films closer to Hollywood models.[133]

Film critic Lata Khubchandani writes, "our earliest films ... had liberal doses of sex and kissing scenes in them. Strangely, it was after Independence the censor board came into being and so did all the strictures."[134] Plots now tend to feature Westernised urbanites dating and dancing in clubs rather than centring on pre-arranged marriages. Though these changes can widely be seen in contemporary Bollywood, traditional conservative ways of Indian culture continue to exist in India outside the industry and an element of resistance by some to western-based influences.[133] Despite this, Bollywood continues to play a major role in fashion in India.[133] Some studies into fashion in India have revealed that some people are unaware that the changing nature of fashion in Bollywood films are often influenced by globalisation; many consider the clothes worn by Bollywood actors as authentically Indian.[133]

Cast and crew

Bollywood employs people from all parts of India. It attracts thousands of aspiring actors and actresses, all hoping for a break in the industry. Models and beauty contestants, television actors, theatre actors and even common people come to Mumbai with the hope and dream of becoming a star.[135] Just as in Hollywood, very few succeed. Since many Bollywood films are shot abroad, many foreign extras are employed too.[136]

Very few non-Indian actors are able to make a mark in Bollywood, though many have tried from time to time. There have been some exceptions, of which one recent example is the hit film Rang De Basanti, where the lead actress is Alice Patten, an Englishwoman. Kisna, Lagaan, and The Rising: Ballad of Mangal Pandey also featured foreign actors. Of late, Emma Brown Garett, an Australian born actress, has starred in a few Indian films.

Bollywood can be very clannish, and the relatives of film-industry insiders have an edge in getting coveted roles in films or being part of a film's crew. However, industry connections are no guarantee of a long career: competition is fierce and if film industry scions do not succeed at the box office, their careers will falter. Some of the biggest stars, such as Dilip Kumar, Dharmendra, Amitabh Bachchan, Rajesh Khanna, Rishi Kapoor, Anil Kapoor, Sunny Deol, Madhuri Dixit and Shah Rukh Khan have succeeded despite a lack of any show business connections. For film clans, see List of Hindi film clans.

Dialogues and lyrics

The film script or lines of dialogue (called "dialogues" in Indian English) and the song lyrics are often written by different people. Dialogues are usually written in an unadorned Hindi-Urdu, collectively known as Hindustani, that would be understood by the largest possible audience.[137] Bollywood films tend to use a colloquial dialect of Hindi-Urdu, mutually intelligible to both Hindi and Urdu speakers.[9] While formally referred to as Hindi cinema, most of its classic scriptwriters actually wrote their scripts and dialogues mainly in Urdu, including the likes of Salim-Javed, Gulzar, Rajinder Singh Bedi, Inder Raj Anand, Rahi Masoom Raza and Wajahat Mirza. Salim-Javed, for example, wrote in Urdu script, with the Urdu dialogues then transcribed by an assistant into Devanagari script so that Hindi readers could read the Urdu dialogues.[10] In the 1970s, the Urdu writers and screenwriters Krishan Chander and Ismat Chughtai noted that "more than seventy-five per cent of films are made in Urdu" but were categorized as Hindi films by the government.[11] Urdu poetry has strongly influenced Bollywood songs, where the lyrics draw heavily from Urdu poetry and the ghazal tradition.[103]

Some movies have used regional dialects to evoke a village setting, or old-fashioned, courtly, formal Urdu in medieval era historical films. Jyotika Virdi, in her book The cinematic imagiNation [sic], wrote about the presence of Urdu in Hindi films: "Urdu is often used in film titles, screenplay, lyrics, the language of love, war, and martyrdom." She notes that Urdu was widely used in classic Hindi cinema, due to formal Urdu being widely taught in pre-partition India and still being used in Hindi cinema decades after partition, but there has since been a decline of formal Urdu in modern Hindi cinema: "The extent of Urdu used in commercial Hindi cinema has not been stable ... the decline of Urdu is mirrored in Hindi films ... It is true that many Urdu words have survived and have become part of Hindi cinema's popular vocabulary. But that is as far as it goes. ... for the most part popular Hindi cinema has forsaken the florid Urdu that was part of its extravagance and retained a "residual" Urdu".[138] The National Science and Media Museum notes that Bollywood films continue to use a colloquial Hindi-Urdu dialect that is mutually intelligible to both Hindi and Urdu speakers.[9] Urdu continues to be extensively used in Bollywood films, in dialogues and particularly songs.[139]

Contemporary mainstream movies also make great use of English (Indian English). According to Bollywood Audiences Editorial, "English has begun to challenge the ideological work done by Urdu."[140] Some movie scripts are first written in Latin script.[141] Characters may shift from one language to the other to express a certain atmosphere (for example, English in a business setting and Hindi in an informal one). The blend of Hindi, Urdu and English occasionally seen in modern Bollywood films is often referred to as Hinglish, which has become increasingly prevalent in modern Bollywood films.[9]

Cinematic language, whether in dialogues or lyrics, is often melodramatic and invokes God, family, mother, duty, and self-sacrifice liberally. Song lyrics are often about love. Bollywood song lyrics, especially in the old movies, frequently use the poetic vocabulary of court Urdu, with many Persian loanwords.[142] Another source for love lyrics is the long Hindu tradition of poetry about the amours of Krishna, Radha, and the gopis, as referenced in films such as Jhanak Jhanak Payal Baje and Lagaan.

Music directors often prefer working with certain lyricists, to the point that the lyricist and composer are seen as a team. This phenomenon is compared to the pairings of American composers and songwriters that created old-time Broadway musicals.

Sound

Sound in Bollywood films was once rarely recorded on location (otherwise known as sync sound). Therefore, the sound was usually created (or re-created) entirely in the studio,[143] with the actors reciting their lines as their images appear on-screen in the studio in the process known as "looping in the sound" or ADR—with the foley and sound effects added later. This created several problems, since the sound in these films usually occurs a frame or two earlier or later than the mouth movements or gestures.[143] The actors had to act twice: once on-location, once in the studio—and the emotional level on set is often very difficult to re-create. Commercial Indian films, not just the Hindi-language variety, are known for their lack of ambient sound, so there is a silence underlying everything instead of the background sound and noises usually employed in films to create aurally perceivable depth and environment.

The ubiquity of ADR in Bollywood cinema became prevalent in the early 1960s with the arrival of the Arriflex 3 camera, which required a blimp (cover) to shield the sound of the camera, for which it was notorious, from on-location filming. Commercial Indian filmmakers, known for their speed, never bothered to blimp the camera, and its excessive noise required that everything had to be re-created in the studio. Eventually, this became the standard for Indian films.

The trend was bucked in 2001, after a 30-year hiatus of synchronised sound, with the film Lagaan, in which the sound was done on the location.[143] This opened up a heated debate on the use and economic feasibility of on-location sound, and several Bollywood films have employed on-location sound since then.

Makeup

In 1955 the Bollywood group Cine Costume Make-Up Artist & Hair Dressers' Association (CCMAA) created a rule that did not allow women to obtain memberships as makeup artists.[144] However, in 2014 the Supreme Court of India ruled that this rule was in violation of the Indian constitutional guarantees granted under Article 14 (right to equality), 19(1)(g) (freedom to carry out any profession) and Article 21 (right to liberty).[144] The judges of the Supreme Court of India stated that the ban on women makeup artist members had no "rationale nexus" to the cause sought to be achieved and was "unacceptable, impermissible and inconsistent" with the constitutional rights guaranteed to the citizens.[144] The Court also found illegal the rule which mandated that for any artist, female or male, to work in the industry, they must have domicile status of five years in the state where they intend to work.[144] In 2015 it was announced that Charu Khurana had become the first woman to be registered by the Cine Costume Make-Up Artist & Hair Dressers' Association.[145]

Bollywood song and dance

Bollywood film music is called filmi music (from Hindi, meaning "of films"). Songs from Bollywood movies are generally pre-recorded by professional playback singers, with the actors then lip synching the words to the song on-screen, often while dancing. While most actors, especially today, are excellent dancers, few are also singers. One notable exception was Kishore Kumar, who starred in several major films in the 1950s while also having a stellar career as a playback singer. K. L. Saigal, Suraiyya, and Noor Jehan were also known as both singers and actors. Some actors in the last thirty years have sung one or more songs themselves; for a list, see Singing actors and actresses in Indian cinema.

Songs are what make and break the movie; they determine if it is going to be a flop or a hit: "Few films without successful musical tracks, and even fewer without any songs and dances, succeed"[146] With the increase of globalization, there has also been a change in the type of music that Bollywood films entail; the lyrics of the songs have increasingly been a mix of Hindi and English languages, as opposed to the strict Hindi prior to Globalization. Also, with the inspiration of global trends, such as Salsa, Pop and Hip Hop, there has been a modification of the type of music heard in Bollywood films.[146]

Playback singers are prominently featured in the opening credits and have their own fans who will go to an otherwise lackluster movie just to hear their favourites. Going by the quality as well as the quantity of the songs they rendered, most notable singers of Bollywood are Lata Mangeshkar, Asha Bhosle, Geeta Dutt, Shamshad Begum, Kavita Krishnamurthy, Sadhana Sargam and Alka Yagnik among female playback singers; and K. L. Saigal, Talat Mahmood, Mukesh, Mohammed Rafi, Manna Dey, Hemant Kumar, Kishore Kumar, Kumar Sanu, Udit Narayan and Sonu Nigam among male playback singers. Kishore Kumar and Mohammed Rafi are often considered arguably the finest of the singers that have lent their voice to Bollywood songs, followed by Lata Mangeshkar, who, through the course of a career spanning over six decades, has recorded thousands of songs for Indian movies. The composers of film music, known as music directors, are also well-known. Their songs can make or break a film and usually do. Remixing of film songs with modern beats and rhythms is a common occurrence today, and producers may even release remixed versions of some of their films' songs along with the films' regular soundtrack albums.

The dancing in Bollywood films, especially older ones, is primarily modelled on Indian dance: classical dance styles, dances of historic northern Indian courtesans (tawaif), or folk dances. In modern films, Indian dance elements often blend with Western dance styles (as seen on MTV or in Broadway musicals), though it is usual to see Western pop and pure classical dance numbers side by side in the same film. The hero or heroine will often perform with a troupe of supporting dancers. Many song-and-dance routines in Indian films feature unrealistically instantaneous shifts of location or changes of costume between verses of a song. If the hero and heroine dance and sing a duet, it is often staged in beautiful natural surroundings or architecturally grand settings. This staging is referred to as a "picturisation".

Songs typically comment on the action taking place in the movie, in several ways. Sometimes, a song is worked into the plot, so that a character has a reason to sing. Other times, a song is an externalisation of a character's thoughts, or presages an event that has not occurred yet in the plot of the movie. In this case, the event is often two characters falling in love. The songs are also often referred to as a "dream sequence", and anything can happen that would not normally happen in the real world.

Previously song and dance scenes often used to be shot in Kashmir, but due to political unrest in Kashmir since the end of the 1980s,[147] those scenes have since then often been shot in Western Europe, particularly in Switzerland and Austria.[148][149]

Renowned contemporary Bollywood dancers include Madhuri Dixit, Hrithik Roshan, Aishwarya Rai Bachchan, Sridevi, Meenakshi Seshadri, Malaika Arora Khan, Shahid Kapoor and Tiger Shroff.[150] Older Bollywood dancers are people such as Helen,[151] known for her cabaret numbers, Madhubala, Vyjanthimala, Padmini, Hema Malini, Mumtaz, Cuckoo Moray,[152] Parveen Babi[153] , Waheeda Rahman,[154] Meena Kumari,[155] and Shammi Kapoor.[156]

For the last few decades Bollywood producers have been releasing the film's soundtrack, as tapes or CDs, before the main movie release, hoping that the music will pull audiences into the cinema later. Often the soundtrack is more popular than the movie. In the last few years some producers have also been releasing music videos, usually featuring a song from the film. However, some promotional videos feature a song which is not included in the movie.

Finances

Bollywood films are multi-million dollar productions, with the most expensive productions costing up to 1 billion rupees (roughly USD 20 million). The latest Science fiction movie Ra.One was made at an immense budget of 1.35 billion (roughly USD 27 million), making it the most expensive movie ever produced in Bollywood.[157] Sets, costumes, special effects, and cinematography were less than world-class up until the mid-to-late 1990s, although with some notable exceptions. As Western films and television gain wider distribution in India itself, there is an increasing pressure for Bollywood films to attain the same production levels, particularly in areas such as action and special effects. Recent Bollywood films have employed international technicians to improve in these areas, such as Krrish (2006) which has action choreographed by Hong Kong based Tony Ching. The increasing accessibility to professional action and special effects, coupled with rising film budgets, has seen an explosion in the action and sci-fi genres.

Sequences shot overseas have proved a real box office draw, so Mumbai film crews are increasingly filming in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, the United States, continental Europe and elsewhere. Nowadays, Indian producers are winning more and more funding for big-budget films shot within India as well, such as Lagaan, Devdas and other recent films.

Funding for Bollywood films often comes from private distributors and a few large studios. Indian banks and financial institutions were forbidden from lending money to movie studios. However, this ban has now been lifted.[158] As finances are not regulated, some funding also comes from illegitimate sources, such as the Mumbai underworld. The Mumbai underworld has been known to be involved in the production of several films, and are notorious for patronising several prominent film personalities. On occasion, they have been known to use money and muscle power to get their way in cinematic deals. In January 2000, Mumbai mafia hitmen shot Rakesh Roshan, a film director and father of star Hrithik Roshan. In 2001, the Central Bureau of Investigation seized all prints of the movie Chori Chori Chupke Chupke after the movie was found to be funded by members of the Mumbai underworld.[159]

Another problem facing Bollywood is widespread copyright infringement of its films. Often, bootleg DVD copies of movies are available before the prints are officially released in cinemas. Manufacturing of bootleg DVD, VCD, and VHS copies of the latest movie titles is a well established 'small scale industry' in parts of South Asia and South East Asia. The Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FICCI) estimates that the Bollywood industry loses $100 million annually in loss of revenue from unlicensed home videos and DVDs. Besides catering to the homegrown market, demand for these copies is large amongst some sections of the Indian diaspora, too. (In fact, bootleg copies are the only way people in Pakistan can watch Bollywood movies, since the Government of Pakistan has banned their sale, distribution and telecast). Films are frequently broadcast without compensation by countless small cable TV companies in India and other parts of South Asia. Small convenience stores run by members of the Indian diaspora in the US and the UK regularly stock tapes and DVDs of dubious provenance, while consumer copying adds to the problem. The availability of illegal copies of movies on the Internet also contributes to the industry's losses.

Satellite TV, television and imported foreign films are making huge inroads into the domestic Indian entertainment market. In the past, most Bollywood films could make money; now fewer tend to do so. However, most Bollywood producers make money, recouping their investments from many sources of revenue, including selling ancillary rights. There are also increasing returns from theatres in Western countries like the United Kingdom, Canada, and the United States, where Bollywood is slowly getting noticed. As more Indians migrate to these countries, they form a growing market for upscale Indian films.

For a comparison of Hollywood and Bollywood financial figures, see chart. It shows tickets sold in 2002 and total revenue estimates. Bollywood sold 3.6 billion tickets and had total revenues (theatre tickets, DVDs, television and so on.) of US$1.3 billion, whereas Hollywood films sold 2.6 billion tickets and generated total revenues (again from all formats) of US$51 billion.

Advertising

Many Indian artists used to make a living by hand-painting movie billboards and posters (The well-known artist M.F. Hussain used to paint film posters early in his career). This was because human labour was found to be cheaper than printing and distributing publicity material.[160] Now, a majority of the huge and ubiquitous billboards in India's major cities are created with computer-printed vinyl. The old hand-painted posters, once regarded as ephemera, are becoming increasingly collectible as folk art.[160][161][162][163]

Releasing the film music, or music videos, before the actual release of the film can also be considered a form of advertising. A popular tune is believed to help pull audiences into the theatres.[164]

Bollywood publicists have begun to use the Internet as a venue for advertising. Most of the better-funded film releases now have their own websites, where browsers can view trailers, stills, and information about the story, cast, and crew.[165]

Bollywood is also used to advertise other products. Product placement, as used in Hollywood, is widely practised in Bollywood.[166]

Bollywood movie stars appear in print and television advertisements for other products, such as watches or soap (see Celebrity endorsement). Advertisers say that a star endorsement boosts sales.

International shoots

With the increasing prominence of international setting such as Switzerland, London, Paris, New York, Brazil, Singapore and so on, it does not entail that the people and cultures residing in these exotic settings are represented. Contrary to these spaces and geographies being filmed as they are, they are actually Indianized by adding Bollywood actors and Hindi speaking extras to them. While immersing in Bollywood films, viewers get to see their local experiences duplicated in different locations around the world.

Rao states that "Media representation can depict India's shifting relation with the world economy, but must retain its 'Indianness' in moments of dynamic hybridity",[146] where "Indianness" refers to the cultural identity and political affiliation. With Bollywood's popularity among diasporic audiences, "Indianness" poses a problem, but at the same time, it gives back to its homeland audience, a sense of uniqueness from other immigrant groups.[167]

Awards

The Filmfare Awards ceremony is one of the most prominent film events given for Hindi films in India.[168] The Indian screen magazine Filmfare started the first Filmfare Awards in 1954, and awards were given to the best films of 1953. The ceremony was referred to as the Clare Awards after the magazine's editor. Modelled after the poll-based merit format of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, individuals may submit their votes in separate categories. A dual voting system was developed in 1956.[169] The Filmfare awards are frequently accused of bias towards commercial success rather than artistic merit.

The National Film Awards were introduced in 1954. Since 1973, the Indian government has sponsored the National Film Awards, awarded by the government run Directorate of Film Festivals (DFF). The DFF screens not only Bollywood films, but films from all the other regional movie industries and independent/art films. These awards are handed out at an annual ceremony presided over by the President of India. Under this system, in contrast to the National Film Awards, which are decided by a panel appointed by Indian Government, the Filmfare Awards are voted for by both the public and a committee of experts.[170]

Notable private awards ceremonies for Hindi films, held within India are:

- Filmfare Awards – since 1954

- Screen Awards – since 1995

- Stardust Awards – since 2003

Notable private awards ceremonies for Hindi films, held overseas are:

- International Indian Film Academy Awards – (different country each year) – since 2000

- Zee Cine Awards- (different country each year) – since 1998

Most of these award ceremonies are lavishly staged spectacles, featuring singing, dancing, and numerous celebrities.

Film education

Global markets

Besides being popular among the South Asian diaspora, in far off locations, from Nigeria and Senegal to Egypt and Russia, generations of non-Indian fans have grown up with Bollywood over the decades, bearing witness to the cross-cultural appeal of Indian films.[171] Indian cinema's early contacts with other regions became visible with its films making early inroads into the Soviet Union, Middle East, Southeast Asia,[172] and China.[173]

Over the last years of the 20th century and beyond, Bollywood progressed in its popularity as it entered the consciousness of Western audiences and producers,[96][174] with Western actors now actively seeking roles in Bollywood movies.[175]

Asia-Pacific

South Asia

Bollywood films are widely watched in other South Asian countries, including Nepal and Pakistan. In these countries, Hindi-Urdu is widely understood.

Many Pakistanis watch Bollywood films, as they understand Hindi (due to its linguistic similarity to Urdu).[176] Pakistan banned the legal import of Bollywood movies in 1965. However, trade in unlicensed DVDs[177] and illegal cable broadcasts ensured the continued popularity of Bollywood releases in Pakistan. Exceptions were made for a few films, such as the 2006 colorized re-release of the classic Mughal-e-Azam or the 2006 film Taj Mahal. Early in 2008, the Pakistani government eased the ban and allowed the import of even more movies; 16 were screened in 2008.[178] Continued easing followed in 2009 and 2010. The new policy is opposed by nationalists and representatives of Pakistan's small film industry but is embraced by cinema owners, who are making profits after years of low receipts.[179] The most popular male actors there are the three Khans of Bollywood: Salman Khan, Shah Rukh Khan, and Aamir Khan. The most popular female actress there was Madhuri Dixit;[180] at India-Pakistan cricket matches in the 1990s, many Pakistani fans frequently chanted the slogan, "Madhuri dedo, Kashmir lelo!" ("Give Madhuri, take Kashmir!").[181]

Bollywood films are very popular in Nepal, to the extent that Bollywood films earn more than Nepali films there. Actors such as Salman Khan, Akshay Kumar and Shah Rukh Khan are most popular in Nepal, with their films having audiences fully pack cinema halls across the country.

Bollywood films also very popular in Afghanistan, due to the country's proximity to the Indian subcontinent and cultural similarities present in the films. For example, India seems to share a similar style of music and musical instruments with Afghanistan. Some of the popular stars there include Shah Rukh Khan, Ajay Devgan, Sunny Deol, Aishwarya Rai, Preity Zinta, and Madhuri Dixit.[182] A number of Bollywood films were filmed inside Afghanistan, while some dealt with the country, including Dharmatma, Kabul Express, Khuda Gawah and Escape From Taliban.[183][184]

Southeast Asia

Bollywood films are popular in Southeast Asia, particularly in Maritime Southeast Asia. The three Khans of Bollywood (Shah Rukh Khan, Aamir Khan, and Salman Khan) are very popular in the Malay world, including Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore. Bollywood is also fairly popular in Thailand.[185]

In Indonesia, due to Indian cultural ties, Bollywood films have been popular in the country, where they were first introduced at the end of World War II in 1945. The "angry young man" films of Amitabh Bachchan and Salim-Javed were popular in the 1970s and 1980s, before Bollywood's popularity gradually began declining in the 1980s and 1990s. Bollywood experienced a revival in Indonesia with the release of Shah Rukh Khan's Kuch Kuch Hota Hai (1998) in 2001, becoming a bigger box-office success there than Titanic (1997). Since then, Bollywood has had a strong presence in Indonesia, particularly Shah Rukh Khan films such as Mohabbatein (2000), Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham (2001), Kal Ho Naa Ho (2003), Chalte Chalte (2003), and Veer-Zaara (2004), as well as Koi Mil Gaya (2003).[186]

East Asia

In East Asia, some Bollywood films are widely appreciated in countries such as China, Japan, and South Korea. In Japan, several Hindi films have a cult following there, such as the films directed by Guru Dutt.[187] Several Hindi films have also had mainstream commercial success in Japan, including Mehboob Khan's Aan (1952) starring Dilip Kumar, and Aziz Mirza's Raju Ban Gaya Gentleman (1992) starring Shah Rukh Khan, which released there in 1997 and sparked a short-lived boom in Indian films released in Japan for the next two years.[188] Another Shah Rukh Khan starrer, Dil Se.. (1998), was also a hit in Japan.[189] The highest-grossing Hindi film in Japan is the Aamir Khan starrer 3 Idiots (2009),[190] which also received a Japanese Academy Award nomination.[191] 3 Idiots was also a critical and commercial success in South Korea.[192]

Some Hindi movies had success in China back in the 1940s and 1950s, and are still popular among older generations of Chinese in the present. Some of the popular Hindi films in the region included Dr. Kotnis Ki Amar Kahani (1946), Awaara (1951) and Do Bigha Zamin (1953). Raj Kapoor was a famous movie star in China, with the song "Awara Hoon" ("I am a Tramp") popular in the country. In China, the few Indian films to gain commercial success there during the 1970s–1980s included Awaara, Tahir Hussain's Caravan (1971), Noorie (1979), and Disco Dancer (1982).[173][193] Famous Indian film stars in China included Raj Kapoor, Nargis,[194] and Mithun Chakraborty.[193] Since the 1980s, Hindi films significantly declined in popularity there,[195] taking decades before Tahir Hussain's son Aamir Khan opened up the Chinese market for Indian films in the early 21st century.[173][196][193] His Academy Award nominated Lagaan (2001) became the first Indian film to have a nationwide release there.[195][197] The Chinese filmmaker He Ping was impressed by Lagaan, especially its soundtrack, and thus hired the film's music composer A. R. Rahman to score the soundtrack for his film Warriors of Heaven and Earth (2003).[198]

When 3 Idiots released in China, the country was only the 15th largest film market, partly due to China's widespread pirate DVD distribution at the time. However, it was the pirate market that introduced 3 Idiots to most Chinese audiences, becoming a cult hit in the country. It became China's 12th favourite film of all time, according to ratings on Chinese film review site Douban, with only one domestic Chinese film (Farewell My Concubine) ranked higher. Aamir Khan gained a large growing Chinese fanbase as a result.[196] After 3 Idiots went viral, several of his other films, such as Taare Zameen Par (2007) and Ghajini (2008), also gained a cult following.[199] By 2013, China grew to become the world's second largest film market (after the United States), paving the way for Aamir Khan's Chinese box office success, with Dhoom 3 (2013), PK (2014), and Dangal (2016),[196] which became the 16th highest-grossing film in China,[200] the fifth highest-grossing non-English language film worldwide,[201] and the highest-grossing non-English foreign film in any market.[202][203][204] Several Aamir Khan films, including Taare Zameen Par, 3 Idiots, and Dangal, are some of the highest-rated films on popular Chinese film site Douban.[205][206] His next film, the Zaira Wasim starrer Secret Superstar (2017), broke Dangal's record for the highest-grossing opening weekend by an Indian film, cementing Aamir Khan's status as a superstar in China,[207] and as "a king of the Chinese box office",[208][209] with Secret Superstar being China's highest-grossing foreign film of 2018 to date.[210] He has become a household name in China,[211] with his success there described as a form of Indian soft power,[212] helping to improve China–India relations, despite political tensions between the two nations.[207][213][194] With Bollywood giving serious competition to Hollywood in the Chinese market,[214] the success of Aamir Khan films has drove up the buyout prices of Indian film imports for Chinese distributors.[215] Salman Khan's Bajrangi Bhaijaan and Irrfan Khan's Hindi Medium also became blockbusters in China during early 2018.[216]

Oceania

Bollywood is not as successful in the Oceanic countries and Pacific Islands such as New Guinea. However, it ranks second to Hollywood in countries such as Fiji, with its large Indian minority, as well as Australia and New Zealand.[217]

Australia is one of the countries where there is a large South Asian diaspora. Bollywood is popular amongst non-Asians in the country as well.[217] Since 1997 the country has provided a backdrop for an increasing number of Bollywood films.[217] Indian filmmakers have been attracted to Australia's diverse locations and landscapes, and initially used it as the setting for song-and-dance sequences, which demonstrated the contrast between the values.[217] However, nowadays, Australian locations are becoming more important to the plot of Bollywood films.[217] Hindi films shot in Australia usually incorporate aspects of Australian lifestyle. The Yash Raj Film Salaam Namaste (2005) became the first Indian film to be shot entirely in Australia and was the most successful Bollywood film of 2005 in the country.[218] This was followed by Heyy Babyy (2007) Chak De! India (2007) and Singh Is Kinng (2008) which turned out to be box office successes.[217] Following the release of Salaam Namaste, on a visit to India the then prime minister John Howard also sought, having seen the film, to have more Indian movies shooting in the country to boost tourism, where the Bollywood and cricket nexus, was further tightened with Steve Waugh's appointment as tourism ambassador to India.[219] Australian actress Tania Zaetta, who co-starred in Salaam Namaste, among other Bollywood films, expressed her keenness to expand her career in Bollywood.[220]

Eastern Europe and Central Asia

Bollywood films are particularly popular in the former Soviet Union (Russia, Eastern Europe, Central Asia).[221] Bollywood films have been dubbed into Russian, and shown in prominent theatres such as Mosfilm and Lenfilm.

Indian films were popular in the Soviet Union, more so than Hollywood films[222][223] and occasionally even domestic Soviet films.[224] The first Indian film to release there was Dharti Ke Lal (1946), directed by Khwaja Ahmad Abbas and based on the Bengal famine of 1943, released in the Soviet Union in 1949.[46] Since then, 300 Indian films were released in the Soviet Union,[225] most of which were Bollywood films, drawing higher average audience figures than domestic Soviet productions,[223][226] with 50 Indian films drawing more than 20 million viewers (compared to 41 Hollywood films),[227][228] with some such as Awaara (1951) and Disco Dancer (1982) drawing more than 60 million viewers,[229][230] establishing Indian actors like Raj Kapoor, Nargis,[230] Rishi Kapoor[231] and Mithun Chakraborty as household names in the country.[232]

Ashok Sharma, Indian Ambassador to Suriname, who has served three times in the Commonwealth of Independent States region during his diplomatic career said:

The popularity of Bollywood in the CIS dates back to the Soviet days when the films from Hollywood and other Western cinema centers were banned in the Soviet Union. As there was no means of other cheap entertainment, the films from Bollywood provided the Soviets a cheap source of entertainment as they were supposed to be non-controversial and non-political. In addition, the Soviet Union was recovering from the onslaught of the Second World War. The films from India, which were also recovering from the disaster of partition and the struggle for freedom from colonial rule, were found to be a good source of providing hope with entertainment to the struggling masses. The aspirations and needs of the people of both countries matched to a great extent. These films were dubbed in Russian and shown in theatres throughout the Soviet Union. The films from Bollywood also strengthened family values, which was a big factor for their popularity with the government authorities in the Soviet Union.[233]

The film Mera Naam Joker (1970), sought to cater to such an appeal and the popularity of Raj Kapoor in Russia, when it recruited Russian actress Kseniya Ryabinkina for the movie. In the contemporary era, Lucky: No Time for Love (2005) was shot entirely in Russia. After the collapse of the Soviet film distribution system, Hollywood occupied the void created in the Russian film market.[221] This made things difficult for Bollywood as it was losing market share to Hollywood. However, Russian newspapers report that there is a renewed interest in Bollywood among young Russians.[234]

In Poland, Bollywood star Shah Rukh Khan has a large following. He was introduced to Polish audiences with the release of Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham (2001) there in 2005, after which some of his other films became hits in the country, including Dil Se (1998), Main Hoon Na (2004) and Kabhi Alvida Naa Kehna (2006). Shah Rukh Khan has become a household name in Poland, and Bollywood films are often covered in the largest Polish newspaper Gazeta Wyborcza.[235][236]

Middle East and North Africa

Hindi films have been popular in Arab countries, including Palestine, Jordan, Egypt, and the Gulf countries.[237] Imported Indian films are usually subtitled in Arabic upon the film's release. Since the early 2000s, Bollywood has progressed in Israel. Special channels dedicated to Indian films have been displayed on cable television.[238] There are channels such as MBC Bollywood and Zee Aflam, which show Hindi movies and serials.[239]

In Egypt, Bollywood films used to be very popular in the 1970s and 1980s. In 1987 however, Bollywood films were restricted to only a handful of films by the Egyptian government.[240][241] Amitabh Bachchan, however, has remained been very popular in Egypt.[242] Indian tourists visiting Egypt are frequently asked by locals, "Do you know Amitabh Bachchan?"[180]

Bollywood movies are regularly screened in Dubai cinemas because of the high demand. Recently in Turkey, Bollywood has been gaining popularity as Barfi! was the first Hindi film to have a wide theatrical release.[243] Bollywood also has viewership in Central Asia (particularly in Uzbekistan[244] and Tajikistan).[245]

South America

Bollywood movies are not influential in many countries of South America, though Bollywood culture and dance is recognised. However, due to significant South Asian diasporic communities in Suriname[246] and Guyana, Hindi-language movies are popular.[247] In 2006, Dhoom 2 became the first Bollywood film to be shot in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.[248]

In January 2012, it was announced that UTV Motion Pictures would be releasing movies in Peru, starting with Guzaarish.[249]

Sub-Saharan Africa and Horn of Africa

Historically, Hindi films have been distributed to some parts of Africa, largely by Lebanese businessmen. Mother India (1957), for example, continued to be played in Nigeria decades after its release. Indian movies have also gained ground so as to alter the style of Hausa fashions, songs have also been copied by Hausa singers and stories have influenced the writings of Nigerian novelists. Stickers of Indian films and stars decorate taxis and buses in Northern Nigeria, while posters of Indian films adorn the walls of tailor shops and mechanics' garages in the country. Unlike in Europe and North America where Indian films largely cater to the expatriate Indian market yearning to keep in touch with their homeland, in West Africa, as in many other parts of the world, such movies rose in popularity despite the lack of a significant Indian audience, where movies are about an alien culture, based on a religion wholly different, and, for the most part, a language that is unintelligible to the viewers. One such explanation for this lies in the similarities between the two cultures. Other similarities include wearing turbans; the presence of animals in markets; porters carrying large bundles, chewing sugar cane; youths riding Bajaj motor scooters; wedding celebrations, and so forth. With the strict Muslim culture, Indian movies were said to show "respect" toward women, where Hollywood movies were seen to have "no shame". In Indian movies women were modestly dressed, men and women rarely kiss, and there is no nudity, thus Indian movies are said to "have culture" that Hollywood films lack. The latter choice was a failure because "they don't base themselves on the problems of the people," where the former is based socialist values and on the reality of developing countries emerging from years of colonialism. Indian movies also allowed for a new youth culture to follow without such ideological baggage as "becoming western."[171] The first ever movie to be shot in Mauritius was Souten starring Rajesh Khanna in 1983.[250]

In South Africa, film imports from India were watched by both Black South African and Indian South African audiences.[251] Several Bollywood personalities have avenued to the continent for both shooting movies and off-camera projects. The film Padmashree Laloo Prasad Yadav (2005) was one of many movies shot in South Africa.[252] Dil Jo Bhi Kahey (2005) was shot almost entirely in Mauritius, which has a large ethnically Indian population.

Ominously, however, the popularity of old Bollywood versus a new, changing Bollywood seems to be diminishing the popularity on the continent. The changing style of Bollywood has begun to question such an acceptance. The new era features more sexually explicit and violent films. Nigerian viewers, for example, commented that older films of the 1950s and 1960s had culture to the newer, more westernised picturisations.[171] The old days of India avidly "advocating decolonization ... and India's policy was wholly influenced by his missionary zeal to end racial domination and discrimination in the African territories" were replaced by newer realities.[253] The emergence of Nollywood, Africa's local movie industry has also contributed to the declining popularity of Bollywood films. A greater globalised world worked in tandem with the sexualisation of Indian films so as to become more like American films, thus negating the preferred values of an old Bollywood and diminishing Indian soft power.

Additionally, classic Bollywood actors like Kishore Kumar and Amitabh Bachchan have historically enjoyed popularity in Egypt and Somalia.[254] In Ethiopia, Bollywood movies are shown alongside Hollywood productions in Piazza theatres, such as the Cinema Ethiopia in Addis Ababa.[255] In the other countries of North Africa, Bollywood films are also broadcast, though local aesthetics tend much more toward expressive or auteur cinema than commercial fare.[256]

Western Europe and North America

The first Indian film to be released in the Western world, and get mainstream attention, was Aan (1952), directed by Mehboob Khan, and starring Dilip Kumar and Nimmi. It was subtitled in 17 languages and released in 28 countries,[251] including the United Kingdom,[257] United States, and France.[258] Aan also received critical acclaim in the British press at the time, such as The Times which compared it favourably with Hollywood productions at the time.[259] Mehboob Khan's later Academy Award-nominated Mother India (1957) was an unprecedented success in overseas markets, including Europe,[259] Russia, the Eastern Bloc, French territories, and Latin America.[260]

The awareness of Hindi cinema is substantial in the United Kingdom,[261] where they frequently enter the UK top ten. The most successful Indian actor at the UK box office has been Shah Rukh Khan, whose popularity in British Asian communities played a key role in introducing Bollywood to the UK,[262] with films such as Darr (1993),[263] Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jayenge (1995),[264] and Kuch Kuch Hota Hai (1998).[262] Dil Se (1998) was the first Indian film to enter the UK top ten.[262] Many Indian films, such as Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jayenge and Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham (2001), have been set in London.