Urdu

| Urdu | |

|---|---|

| اُردُو | |

Urdu in Nastaʿlīq script | |

| Pronunciation |

[ˈʊrdu] ( |

| Region | South Asia (native to the Hindi-Urdu Belt) |

| Ethnicity | Hindustani people, Deccani Muslims, and Muhajirs |

Native speakers |

50.7 million in India[1] 16 million in Pakistan[2] (2007 & 2017) |

| |

| Official status | |

Official language in |

Official: Secondary Official: |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 |

ur |

| ISO 639-2 |

urd |

| ISO 639-3 |

urd |

| Glottolog |

urdu1245[9] |

| Linguasphere |

59-AAF-q |

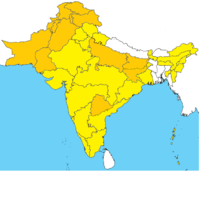

Areas in India and Pakistan where Urdu is either official or co-official

Areas where Urdu is neither official nor co-official | |

Urdu (/ˈʊərduː/;[10] Urdu: اُردُو ALA-LC: Urdū [ˈʊrduː] (![]()

Apart from specialized vocabulary, spoken Urdu is mutually intelligible with Standard Hindi, another recognized register of Hindustani. The Urdu variant of Hindustani received recognition and patronage under British rule when the British replaced the local official languages with English and Hindustani written in Nastaʿlīq script, as the official language in North and Northwestern India.[13][14][15] Religious, social, and political factors pushed for a distinction between Urdu and Hindi in India, leading to the Hindi–Urdu controversy.[16]

According to Nationalencyklopedin's 2010 estimates, Urdu is the 21st most spoken first language in the world, with approximately 66 million speakers.[17] According to Ethnologue's 2017 estimates, Urdu, along with standard Hindi and the languages of the Hindi belt (as Hindustani), is the 3rd most spoken language in the world, with approximately 329.1 million native speakers, and 697.4 million total speakers.[18]

Origin

Urdu, like Hindi, is a form of Hindustani.[19] It evolved from the medieval (6th to 13th century) Apabhraṃśa register of the preceding Shauraseni language, a Middle Indo-Aryan language that is also the ancestor of other modern Indo-Aryan languages, including the Punjabi dialects. Around 75% of Urdu words have their etymological roots in Sanskrit and Prakrit,[20][21][22] and approximately 99% of Urdu verbs have their roots in Sanskrit and Prakrit.[23] Because Persian-speaking sultans ruled the Indian subcontinent for a number of years,[24] Urdu was influenced by Persian and to a lesser extent, Arabic, which have contributed to about 25% of Urdu's vocabulary.[20][25][26][27][28][29][30] Although the word Urdu is derived from the Turkic word ordu (army) or orda, from which English horde is also derived,[31] Turkic borrowings in Urdu are minimal[32] and Urdu is also not genetically related to the Turkic languages. Urdu words originating from Chagatai and Arabic were borrowed through Persian and hence are Persianized versions of the original words. For instance, the Arabic ta' marbuta ( ة ) changes to he ( ه ) or te ( ت ).[33][note 1] Nevertheless, contrary to popular belief, Urdu did not borrow from the Turkish language, but from Chagatai, a Turkic language from Central Asia. Urdu and Turkish borrowed from Arabic and Persian, hence the similarity in pronunciation of many Urdu and Turkish words.[34]

Arabic influence in the region began with the late first-millennium Muslim conquests of the Indian subcontinent. The Persian language was introduced into the subcontinent a few centuries later by various Persianized Central Asian Turkic and Afghan dynasties including that of Mahmud of Ghazni.[35][36] The Turko-Afghan Delhi Sultanate established Persian as its official language, a policy continued by the Mughal Empire, which extended over most of northern South Asia from the 16th to 18th centuries and cemented Persian influence on the developing Hindustani.

The name Urdu was first used by the poet Ghulam Hamadani Mushafi around 1780.[37][38](p18) From the 13th century until the end of the 18th century Urdu was commonly known as Hindi.[38](p1) The language was also known by various other names such as Hindavi and Dehlavi.[38](pp21–22) Hindustani in Persian script was used by Muslims and Hindus, but was current chiefly in Muslim-influenced society.[39] The communal nature of the language lasted until it replaced Persian as the official language in 1837 and was made co-official, along with English. Hindustani was promoted in British India by British policies to counter the previous emphasis on Persian.[40] This triggered a Hindu backlash in northwestern India, which argued that the language should be written in the native Devanagari script. This literary standard called "Hindi" replaced Urdu as the official language of Bihar in 1881, establishing a sectarian divide of "Urdu" for Muslims and "Hindi" for Hindus, a divide that was formalized with the division of India and Pakistan after independence (though there are Hindu poets who continue to write in Urdu to this day, with post-independence examples including Gopi Chand Narang and Gulzar).

There have been attempts to "purify" Urdu and Hindi, by purging Urdu of Sanskrit words, and Hindi of Persian loanwords, and new vocabulary draws primarily from Persian and Arabic for Urdu and from Sanskrit for Hindi. English has exerted a heavy influence on both as a co-official language.[41]

Speakers and geographic distribution

There are over 100 million native speakers of Urdu in India (more than 80% of it) and Pakistan together: there were 52 million and 80.5 million Urdu speakers in India some 5% and 6.5% of the total population of India as per the 2001 and 2011 censuses respectively;[42] approximately 10 million in Pakistan or 7.57% as per the 1998 census and 16 million in 2006 estimates;[43] and several hundred thousand in the United Kingdom, Saudi Arabia, United States, and Bangladesh (where it is called "Bihari").[44] However, a knowledge of Urdu allows one to speak with far more people than that, because Hindustani, of which Urdu is one variety, is the third most commonly spoken language in the world, after Mandarin and English .[45] Because of the difficulty in distinguishing between Urdu and Hindi speakers in India and Pakistan, as well as estimating the number of people for whom Urdu is a second language, the estimated number of speakers is uncertain and controversial.

Owing to interaction with other languages, Urdu has become localized wherever it is spoken, including in Pakistan. Urdu in Pakistan has undergone changes and has incorporated and borrowed many words from regional languages, thus allowing speakers of the language in Pakistan to distinguish themselves more easily and giving the language a decidedly Pakistani flavour. Similarly, the Urdu spoken in India can also be distinguished into many dialects like Dakhni (Deccan) of South India, and Khariboli of the Punjab region. Because of Urdu's similarity to Hindi, speakers of the two languages can easily understand one another if both sides refrain from using specialized vocabulary. The syntax (grammar), morphology, and the core vocabulary are essentially identical. Thus linguists usually count them as one single language and contend that they are considered as two different languages for socio-political reasons.[46]

In Pakistan, Urdu is mostly learned as a second or a third language as nearly 93% of Pakistan's population has a native language other than Urdu. Despite this, Urdu was chosen as a token of unity and as a lingua franca so as not to give any native Pakistani language preference over the other. Urdu is therefore spoken and understood by the vast majority in some form or another, including a majority of urban dwellers in such cities as Karachi, Lahore, Okara District, Sialkot, Rawalpindi, Islamabad, Multan, Faisalabad, Hyderabad, Peshawar, Quetta, Jhang, Sargodha and Skardu. It is written, spoken and used in all provinces/territories of Pakistan although the people from differing provinces may have different indigenous languages, as from the fact that it is the "base language" of the country. For this reason, it is also taught as a compulsory subject up to higher secondary school in both English and Urdu medium school systems. This has produced millions of Urdu speakers from people whose native language is one of the other languages of Pakistan, who can read and write only Urdu. It is absorbing many words from the regional languages of Pakistan. This variation of Urdu is sometimes referred to as Pakistani Urdu.

Although most of the population is conversant in Urdu, it is the first language of only an estimated 7% of the population who are mainly Muslim immigrants (known as Muhajir in Pakistan) from different parts of South Asia. The regional languages are also being influenced by Urdu vocabulary. There are millions of Pakistanis whose native language is not Urdu, but because they have studied in Urdu medium schools, they can read and write Urdu along with their native language. Most of the nearly five million Afghan refugees of different ethnic origins (such as Pashtun, Tajik, Uzbek, Hazarvi, and Turkmen) who stayed in Pakistan for over twenty-five years have also become fluent in Urdu. With such a large number of people(s) speaking Urdu, the language has acquired a peculiar Pakistani flavour further distinguishing it from the Urdu spoken by native speakers and diversifying the language even further.

Many newspapers are published in Urdu in Pakistan, including the Daily Jang, Nawa-i-Waqt, Millat, among many others (see List of newspapers in Pakistan#Urdu language newspapers).

In India, Urdu is spoken in places where there are large Muslim minorities or cities that were bases for Muslim Empires in the past. These include parts of Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Bihar, Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra (Marathwada), Karnataka and cities such as Lucknow, Delhi, Bareilly, Meerut, Saharanpur, Muzaffarnagar, Roorkee, Deoband, Moradabad, Azamgarh, Bijnor, Najibabad, Rampur, Aligarh, Allahabad, Gorakhpur, Agra, Kanpur, Badaun, Bhopal, Hyderabad, Aurangabad, Bangalore, Kolkata, Mysore, Patna, Gulbarga, Parbhani, Nanded,Kochi, Malegaon, Bidar, Ajmer, and Ahmedabad.[47] Some Indian schools teach Urdu as a first language and have their own syllabi and exams. Indian madrasahs also teach Arabic as well as Urdu. India has more than 3,000 Urdu publications, including 405 daily Urdu newspapers. Newspapers such as Neshat News Urdu, Sahara Urdu, Daily Salar, Hindustan Express, Daily Pasban, Siasat Daily, The Munsif Daily and Inqilab are published and distributed in Bangalore, Malegaon, Mysore, Hyderabad, and Mumbai (see List of newspapers in India).

Outside South Asia, it is spoken by large numbers of migrant South Asian workers in the major urban centres of the Persian Gulf countries. Urdu is also spoken by large numbers of immigrants and their children in the major urban centres of the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Germany, Norway, and Australia. Along with Arabic, Urdu is among the immigrant languages with the most speakers in Catalonia.[48]

Cultural identity and Islam

Colonial India

Religious and social atmospheres in early nineteenth century India played a significant role in the development of the Urdu register. In addition to Islam, India was characterized by a number of other religions that represented different spiritual outlooks. Hindi became the distinct register spoken by those who sought to construct a Hindu identity in the face of colonial rule.[16] As Hindi separated from Hindustani to create a distinct spiritual identity, Urdu was employed to create a definitive Islamic identity for the Muslim population in India.[49]

As Urdu and Hindi became means of religious and social construction for Muslims and Hindus respectively, each register developed its own script. According to Islamic tradition, Arabic, the language spoken by the prophet Muhammad and uttered in the revelation of the Qur'an, holds spiritual significance and power.[50] Because Urdu was intentioned as means of unification for Muslims in Northern India and later Pakistan, it adopted an Arabic script.[51][16]

.jpg)

Pakistan

Urdu continued its role in developing a Muslim identity as the Islamic Republic of Pakistan was established with the intent to construct a homeland for Islamic believers. Several languages and dialects spoken throughout the regions of Pakistan produced an imminent need for a uniting language. Because Urdu was the symbol of Islamic identity in Northern India, it was selected as the national language for Pakistan. While Urdu and Islam together played important roles in developing the national identity of Pakistan, disputes in the 1950s (particularly those in East Pakistan), challenged the necessity for Urdu as a national symbol and its practicality as the lingua franca. The significance of Urdu as a national symbol was downplayed by these disputes when English and Bengali were also accepted as official languages in East Pakistan (now Bangladesh).

Official status

Urdu is the national and one of the two official languages of Pakistan, along with English, and is spoken and understood throughout the country, whereas the state-by-state languages (languages spoken throughout various regions) are the provincial languages. Only 7.57% of Pakistanis have Urdu as their first language,[52] but Urdu is mostly understood and spoken all over Pakistan as a second or third language. It is used in education, literature, office and court business.[53] It holds in itself a repository of the cultural and social heritage of the country.[54] Although English is used in most elite circles, and Punjabi has a plurality of native speakers, Urdu is the lingua franca and national language of Pakistan. In practice English is used instead of Urdu in the higher echelons of government.[55]

Urdu is also one of the officially recognized languages in India and the official language of Jammu and Kashmir, one of the two official languages of Telangana and also has the status of "additional official language" in the Indian states of Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Jharkhand, West Bengal and the national capital, New Delhi.[56]

In Jammu and Kashmir, section 145 of the Kashmir Constitution provides: "The official language of the State shall be Urdu but the English language shall unless the Legislature by law otherwise provides, continue to be used for all the official purposes of the State for which it was being used immediately before the commencement of the Constitution."[57]

Dialects

Urdu has a few recognised dialects, including Dakhni, Rekhta, and Modern Vernacular Urdu (based on the Khariboli dialect of the Delhi region). Dakhni (also known as Dakani, Deccani, Desia, Mirgan) is spoken in Deccan region of southern India. It is distinct by its mixture of vocabulary from Marathi and Konkani, as well as some vocabulary from Arabic, Persian and Chagatai that are not found in the standard dialect of Urdu. Dakhini is widely spoken in all parts of Maharashtra, Telangana, Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka. Urdu is read and written as in other parts of India. A number of daily newspapers and several monthly magazines in Urdu are published in these states. In terms of pronunciation, the easiest way to recognize native speakers is by their pronunciation of the letter "qāf" (ق) as "k̲h̲e" (خ).

Code switching

Many bilingual or multi-lingual Urdu speakers, being familiar with both Urdu and English, display code-switching (referred to as "Urdish") in certain localities and between certain social groups.

On 14 August 2015, the Government of Pakistan launched the Ilm Pakistan movement, with a uniform curriculum in Urdish. Ahsan Iqbal, Federal Minister of Pakistan, said, "Now the government is working on a new curriculum to provide a new medium to the students which will be the combination of both Urdu and English and will name it Urdish."[58][59][60]

Comparison with Modern Standard Hindi

Standard Urdu is often contrasted with Standard Hindi.[61] Apart from religious associations, the differences are largely restricted to the standard forms: Standard Urdu is conventionally written in the Nastaliq style of the Persian alphabet and relies heavily on Persian and Arabic as a source for technical and literary vocabulary,[62] whereas Standard Hindi is conventionally written in Devanāgarī and draws on Sanskrit.[63] However, both have large numbers of Arabic, Persian and Sanskrit words, and most linguists consider them to be two standardised forms of the same language,[64][65] and consider the differences to be sociolinguistic,[66] though a few classify them separately.[67] Old Urdu dictionaries also contain most of the Sanskrit words now present in Hindi.[68][69] Mutual intelligibility decreases in literary and specialized contexts that rely on educated vocabulary. Further, it is quite easy in a longer conversation to distinguish differences in vocabulary and pronunciation of some Urdu phonemes. As a result of religious nationalism since the partition of British India and continued communal tensions, native speakers of both Hindi and Urdu frequently assert them to be distinct languages, despite the numerous similarities between the two in a colloquial setting.

The barrier created between Hindi and Urdu is eroding: Hindi speakers are comfortable with using Persian-Arabic borrowed words[70] and Urdu speakers are also comfortable with using Sanskrit terminology.[71][72]

Phonology

Consonants

| Bilabial | Dental/ Alveolar |

Retroflex | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | plain | m | n | ŋ | ||||

| voiced aspirated | (mʱ) | (nʱ) | ||||||

| Plosive/ Affricate |

voiceless | p | t | ʈ | tʃ | k | q | (ʔ) |

| voiceless aspirated | pʰ | tʰ | ʈʰ | tʃʰ | kʰ | |||

| voiced | b | d | ɖ | dʒ | ɡ | ɢ | ||

| voiced aspirated | bʱ | dʱ | ɖʱ | dʒʱ | ɡʱ | |||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | ʃ | x | (h) | ||

| voiced | v | z | ʒ | ɣ | ɦ | |||

| Flap | plain | ɾ | ɽ | |||||

| voiced aspirated | (ɾʱ) | ɽʱ | ||||||

| Approximant | plain | ʋ | l | j | ||||

| voiced aspirated | (lʱ) | |||||||

- Notes

- Marginal and non-universal phonemes are in parentheses.

- /ɣ/ is post-velar.[75]

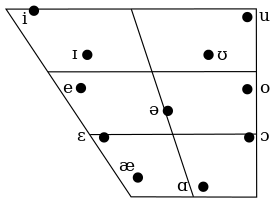

Vowels

| Front | Central | Back | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| short | long | short | long | short | long | ||

| Close | oral | ɪ | iː | ʊ | uː | ||

| nasal | ɪ̃ | ĩː | ʊ̃ | ũː | |||

| Close-mid | oral | (e) | eː | ə | (o) | oː | |

| nasal | ẽː | ə̃ | õː | ||||

| Open-mid | oral | (ɛ) | ɛː | (ɔ) | ɔː | ||

| nasal | ɛ̃ː | ɔ̃ː | |||||

| Open | oral | æː | ɑː | ||||

| nasal | ɑ̃ː | ||||||

- Note

- Marginal and non-universal vowels are in parentheses.

Vocabulary

The author of Farhang-i-Aasifiya, considered to be the most reliable and comprehensive Urdu dictionary, stated that Urdu vocabulary has a 75% core of Prakrit and Sanskrit-derived words,[20][21][22] with approximately 25% of its vocabulary being Persian and Arabic loanwords.[20][21][22] However, a paper published in the Journal of Pakistan Vision places Urdu vocabularly as being composed of 29.9% of Arabic loanwords and 21.7% Persian loanwords.[76][77] Many of the words of Arabic origin have been adopted through Persian,[20] and have different pronunciations and nuances of meaning and usage than they do in Arabic. There are also a smaller number of borrowings from Chagatai, and Portuguese.

Levels of formality

Urdu in its less formalised register has been referred to as a rek̤h̤tah (ریختہ, [reːxtaː]), meaning "rough mixture". The more formal register of Urdu is sometimes referred to as zabān-i Urdū-yi muʿallá (زبانِ اُردُوئے معلّٰى [zəbaːn eː ʊrdu eː moəllaː]), the "Language of the Exalted Camp", referring to the Imperial army.[78]

The etymology of the word used in the Urdu language for the most part decides how polite or refined one's speech is. For example, Urdu speakers would distinguish between پانی pānī and آب āb, both meaning "water"; the former is used colloquially and has older Indic origins, whereas the latter is used formally and poetically, being of Persian origin.

If a word is of Persian or Arabic origin, the level of speech is considered to be more formal and grand. Similarly, if Persian or Arabic grammar constructs, such as the izafat, are used in Urdu, the level of speech is also considered more formal and grand. If a word is inherited from Sanskrit, the level of speech is considered more colloquial and personal.[79] This distinction is similar to the division in English between words of Latin, French and Old English origins.

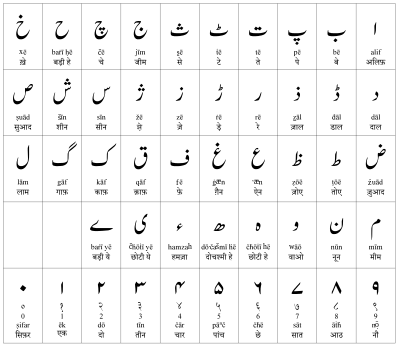

Writing system

Urdu is written right-to left in an extension of the Persian alphabet, which is itself an extension of the Arabic alphabet. Urdu is associated with the Nastaʿlīq style of Persian calligraphy, whereas Arabic is generally written in the Naskh or Ruq'ah styles. Nasta’liq is notoriously difficult to typeset, so Urdu newspapers were hand-written by masters of calligraphy, known as kātib or khush-nawīs, until the late 1980s. One handwritten Urdu newspaper, The Musalman, is still published daily in Chennai.[80]

A highly Persianized and technical form of Urdu was the lingua franca of the law courts of the British administration in Bengal, Bihar, and the North-West Provinces & Oudh. Until the late 19th century, all proceedings and court transactions in this register of Urdu were written officially in the Persian script. In 1880, Sir Ashley Eden, the Lieutenant-Governor of Bengal abolished the use of the Persian alphabet in the law courts of Bengal and Bihar and ordered the exclusive use of Kaithi, a popular script used for both Urdu and Hindi.[81] Kaithi's association with Urdu and Hindi was ultimately eliminated by the political contest between these languages and their scripts, in which the Persian script was definitively linked to Urdu.

More recently in India, Urdu speakers have adopted Devanagari for publishing Urdu periodicals and have innovated new strategies to mark Urdu in Devanagari as distinct from Hindi in Devanagari. Such publishers have introduced new orthographic features into Devanagari for the purpose of representing the Perso-Arabic etymology of Urdu words. One example is the use of अ (Devanagari a) with vowel signs to mimic contexts of ع (‘ain), in violation of Hindi orthographic rules. For Urdu publishers, the use of Devanagari gives them a greater audience, whereas the orthographic changes help them preserve a distinct identity of Urdu.[82]

Literature

Urdu has become a literary language only in recent centuries, as Persian was formerly the idiom of choice for the Muslim courts of North India. However, despite its relatively late development, Urdu literature boasts of some world-recognised artists and a considerable corpus.

Prose

Urdu afsana is a kind of Urdu prose in which many experiments have been done by short story writers from Munshi Prem Chand, Sadat Hasan Manto, Rajindra Singh Bedi, Ismat Chughtai, Krishan Chandra to Naeem Baig. and Rahman Abbas.

Religious

Urdu holds the largest collection of works on Islamic literature and Sharia. These include translations and interpretation of the Qur'an as well as commentary on Hadith, Fiqh, history, and Sufism. A great number of classical texts from Arabic and Persian have also been translated into Urdu. Relatively inexpensive publishing, combined with the use of Urdu as a lingua franca among Muslims of South Asia, has meant that Islam-related works in Urdu far outnumber such works in any other South Asian language. Popular Islamic books are also written in Urdu.

A treatise on astrology was penned in Urdu by Pandit Roop Chand Joshi in the twentieth century. The book, known as Lal Kitab, is widely popular in North India among astrologers.

Literary

Secular prose includes all categories of widely known fiction and non-fiction work, separable into genres. The dāstān, or tale, a traditional story that may have many characters and complex plotting. This has now fallen into disuse.

The afsāna or short story is probably the best-known genre of Urdu fiction. The best-known afsāna writers, or afsāna nigār, in Urdu are Munshi Premchand, Saadat Hasan Manto, Rajinder Singh Bedi, Krishan Chander, Qurratulain Hyder (Qurat-ul-Ain Haider), Ismat Chughtai, Ghulam Abbas, Rashid ul Khairi and Ahmad Nadeem Qasimi till Rahman Abbas. Towards the end of last century Paigham Afaqui's novel Makaan appeared with a reviving force for Urdu novel resulting into writing of novels getting a boost in Urdu literature and a number of writers like Ghazanfer, Abdus Samad, Sarwat Khan and Musharraf Alam Zauqi have taken the move forward. However, Rahman Abbas has emerged as the most influential Urdu Novelist in 21st Century and he has raises the art of story-telling to a new level.[83]

Munshi Premchand, became known as a pioneer in the afsāna, though some contend that his were not technically the first as Sir Ross Masood had already written many short stories in Urdu. Novels form a genre of their own, in the tradition of the English novel. Other genres include saférnāma (travel story), mazmoon (essay), sarguzisht (account/narrative), inshaeya (satirical essay), murasela (editorial), and khud navvisht (autobiography).

Poetry

Urdu has been one of the premier languages of poetry in South Asia for two centuries, and has developed a rich tradition in a variety of poetic genres. The Ghazal in Urdu represents the most popular form of subjective music and poetry, whereas the Nazm exemplifies the objective kind, often reserved for narrative, descriptive, didactic or satirical purposes. Under the broad head of the Nazm we may also include the classical forms of poems known by specific names such as Masnavi (a long narrative poem in rhyming couplets on any theme: romantic, religious, or didactic), Marsia (an elegy traditionally meant to commemorate the martyrdom of Husayn ibn Ali, grandson of Muhammad, and his comrades of the Karbala fame), or Qasida (a panegyric written in praise of a king or a nobleman), for all these poems have a single presiding subject, logically developed and concluded. However, these poetic species have an old world aura about their subject and style, and are different from the modern Nazm, supposed to have come into vogue in the later part of the nineteenth century. Probably the most widely recited, and memorised genre of contemporary Urdu poetry is nāt—panegyric poetry written in praise of Muhammad. Nāt can be of any formal category, but is most commonly in the ghazal form. The language used in Urdu nāt ranges from the intensely colloquial to a highly persified formal language. The great early 20th century scholar Ala Hazrat, Ahmed Raza Khan Barelvi, who wrote many of the most well known nāts in Urdu (the collection of his poetic work is Hadaiq-e-Baqhshish), epitomised this range in a ghazal of nine stanzas (bayt) in which every stanza contains half a line each of Arabic, Persian, formal Urdu, and colloquial Hindi.

Another important genre of Urdu prose are the poems commemorating the martyrdom of Husayn ibn Ali at the Battle of Karbala, called noha (نوحہ) and marsia. Anees and Dabeer are famous in this regard.

Terminologies

As̱ẖʿār (اشعار, verse, couplets): It consists of two hemistiches (lines) called Miṣraʿ (مصرع); first hemistich (line) is called مصرعِ اولٰی (Miṣraʿ-i ūlá) and the second is called (مصرعِ ثانی) (Miṣraʿ-i s̱ānī). Each verse embodies a single thought or subject (singular) شِعر shiʿr.

In the Urdu poetic tradition, most poets use a pen name called the takhalluṣ. This can be either a part of a poet's given name or something else adopted as an identity. The traditional convention in identifying Urdu poets is to mention the takhalluṣ at the end of the name. Thus Ghalib, whose official name and title was Mirza Asadullah Beg Khan, is referred to formally as Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib, or in common parlance as just Mirza Ghalib. Because the takhalluṣ can be a part of their actual name, some poets end up having that part of their name repeated, such as Faiz Ahmad Faiz.

The word takhalluṣ is derived from Arabic, meaning "ending". This is because in the ghazal form, the poet would usually incorporate his or her pen name into the final couplet (maqt̤aʿ) of each poem as a type of "signature".

Urdu poetry example

This is Ghalib's famous couplet in which he compares himself to his great predecessor, the master poet Mir:[84]

ریختے کے تمہیں استاد نہیں ہو غالبؔ | ؎ | ||

کہتے ہیں اگلے زمانے میں کوئی میرؔ بھی تھا |

Transliteration

- Reḵẖtah ke tumhī ustād nahīṉ ho G̱ẖālib

- Kahte haiṉ Agle zamāne meṉ ko'ī Mīr bhī thā

Translation

Sample text

The following is a sample text in Urdu, of the Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (by the United Nations):

Urdu text

- دفعہ ۱: تمام انسان آزاد اور حقوق و عزت کے اعتبار سے برابر پیدا ہوئے ہیں۔ انہیں ضمیر اور عقل ودیعت ہوئی ہے۔ اس لیے انہیں ایک دوسرے کے ساتھ بھائی چارے کا سلوک کرنا چاہئے۔

Transliteration (ALA-LC)

- Dafʿah 1: Tamām insān āzād aur ḥuqūq o ʿizzat ke iʿtibār se barābar paidā hūʾe haiṉ. Unheṉ ẓamīr aur ʿaql wadīʿat hūʾī hai. Is liʾe unheṉ ek dūsre ke sāth bhāʾī chāre kā sulūk karnā cāhiʾe.

IPA transcription

- dəfɑː eːk: təmɑːm ɪnsɑːn ɑːzɑːd ɔːr hʊquːq oː ɪzzət keː etɪbɑːr seː bərɑːbər pɛːdɑː ɦuːeː ɦɛ̃ː. ʊnɦẽː zəmiːr ɔːr əql ʋədiːət huːiː hɛː. ɪs lieː ʊnɦẽː eːk duːsreː keː sɑːtʰ bʱaːiː t͡ʃɑːreː kɑː sʊluːk kərnɑː t͡ʃɑːɦieː.

Gloss (word-for-word)

- Article 1: All humans free[,] and rights and dignity *('s) consideration from equal born are. Them to conscience and intellect endowed is. This for, they one another *('s) with brotherhood *('s) treatment do should.

Translation (grammatical)

- Article 1: All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience. Therefore, they should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

Note: *('s) represents a possessive case that, when written, is preceded by the possessor and followed by the possessed, unlike the English "of".

See also

- Hindi–Urdu controversy

- List of Urdu-language poets

- List of Urdu-language writers

- National Translation Mission (NTM)

- Persian and Urdu

- States of India by Urdu speakers

- Urdu in the United Kingdom

- Uddin and Begum Hindustani Romanisation

- Urdu Digest

- Urdu in Aurangabad

- Urdu Informatics

- Urdu keyboard

- Glossary of the British Raj

Notes

- ↑ An example can be seen in the word "need" in Urdu. Urdu uses the Persian version ضرورت rather than the original Arabic ضرورة. See: John T. Platts "A dictionary of Urdu, classical Hindi, and English" (1884) Page 749. Urdu also use Persian pronunciation – for instance rather than pronouncing ض as "ḍ" an emphatic consonant, the original sound in Arabic, Urdu uses the Persian pronunciation "z". See: John T. Platts "A dictionary of Urdu, classical Hindi, and English" (1884) Page 748

- ↑ Rekhta was the name for the Urdu language in Ghalib's days.

References

- ↑ "Scheduled Languages in descending order of speaker's strength - 2011" (PDF). Registrar General and Census Commissioner of India. 29 June 2018.

- ↑ "Population by Mother Tongue | Pakistan Bureau of Statistics". www.pbs.gov.pk. Archived from the original on 12 July 2017. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- 1 2 Hindustani (2005). Keith Brown, ed. Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics (2 ed.). Elsevier. ISBN 0-08-044299-4.

- ↑ Gaurav Takkar. "Short Term Programmes". punarbhava.in. Archived from the original on 15 November 2016. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- ↑ "Indo-Pakistani Sign Language", Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics

- ↑ "Urdu is Telangana's second official language". The Indian Express. 2017-11-16. Retrieved 2018-02-27.

- ↑ "Urdu is second official language in Telangana as state passes Bill". The News Minute. 2017-11-17. Retrieved 2018-02-27.

- ↑ "The World Fact Book". Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 16 July 2017.

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Urdu". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ "Urdu" Archived 19 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine.. Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ↑ "NIST 2007 Language Recognition Evaluation" (PDF). Alvin F. Martin, Audrey N. Le. Speech Group, Information Access Division, Information Technology Laboratory National Institute of Standards and Technology, USA. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 July 2016.

- ↑ Rao, Chaitra, et al. "Orthographic characteristics speed Hindi word naming but slow Urdu naming: evidence from Hindi/Urdu biliterates." Reading and Writing 24.6 (2011): 679–695.

- ↑ Brass, Paul R. (2005). Language, religion and politics in North India. Lincoln, NE: IUniverse. ISBN 978-0-595-34394-2.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 September 2012. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

- ↑ Mohanty, Panchanan. "British language policy in 19th century India and the Oriya language movement." Language Policy 1.1 (2002): 53–73.

- 1 2 3 Ahmad, Rizwan (2008-07-01). "Scripting a new identity: The battle for Devanagari in nineteenth century India". Journal of Pragmatics. 40 (7): 1163–1183. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2007.06.005.

- ↑ Mikael Parkvall, "Världens 100 största språk 2007" (The World's 100 Largest Languages in 2007), in Nationalencyklopedin. Asterisks mark the 2010 estimates Archived 11 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine. for the top dozen languages.

- ↑ "Language Size".

- ↑ Maria Isabel Maldonado Garcia (2015). Urdu Evolution and Reforms. Punjab University Department of Press and Publications, Lahore, Pakistan. p. 223.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ahmad, Aijaz (2002). Lineages of the Present: Ideology and Politics in Contemporary South Asia. Verso. p. 113. ISBN 9781859843581.

On this there are far more reliable statistics than those on population. Farhang-e-Asafiya is by general agreement the most reliable Urdu dictionary. It twas compiled in the late nineteenth century by an Indian scholar little exposed to British or Orientalist scholarship. The lexicographer in question, Syed Ahmed Dehlavi, had no desire to sunder Urdu's relationship with Farsi, as is evident even from the title of his dictionary. He estimates that roughly 75 per cent of the total stock of 55,000 Urdu words that he compiled in his dictionary are derived from Sanskrit and Prakrit, and that the entire stock of the base words of the language, without exception, are derived from these sources. What distinguishes Urdu from a great many other Indian languauges ... is that is draws almost a quarter of its vocabulary from language communities to the west of India, such as Farsi, Turkish, and Tajik. Most of the little it takes from Arabic has not come directly but through Farsi.

- 1 2 3 Dalmia, Vasudha (31 July 2017). Hindu Pasts: Women, Religion, Histories. SUNY Press. p. 310. ISBN 9781438468075.

On the issue of vocabulary, Ahmad goes on to cite Syed Ahmad Dehlavi as he set about to compile the Farhang-e-Asafiya, an Urdu dictionary, in the late nineteenth century. Syed Ahmad 'had no desire to sunder Urdu's relationship with Farsi, as is evident from the title of his dictionary. He estimates that roughly 75 per cent of the total stock of 55.000 Urdu words that he compiled in his dictionary are derived from Sanskrit and Prakrit, and that the entire stock of the base words of the language, without exception, are from these sources' (2000: 112-13). As Ahmad points out, Syed Ahmad, as a member of Delhi's aristocratic elite, had a clear bias towards Persian and Arabic. His estimate of the percentage of Prakitic words in urdu should therefore be considered more conservative than not. The actual proportion of Prakitic words in everyday language would clearly be much higher.

- 1 2 3 Taj, Afroz (1997). "About Hindi-Urdu". University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ↑ "Urdu's origin: it's not a "camp language"". dawn.com. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 5 July 2015.

- ↑ First Encyclopaedia of Islam: 1913-1936. Brill Academic Publishers. 1993. p. 1024. ISBN 9789004097964.

Whilst the Muhammadan rulers of India spoke Persian, which enjoyed the prestige of being their court language, the common language of the country continued to be Hindi, derived through Prakrit from Sanskrit. On this dialect of the common people was grafted the Persian language, which brought a new language, Urdu, into existence. Sir George Grierson, in the Linguistic Survey of India, assigns no distinct place to Urdu, but treats it as an offshoot of Western Hindi.

- ↑ Rauf Parekh. "Literary Notes: Common misconceptions about Urdu". dawn.com. Archived from the original on 25 January 2015. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- ↑ "Two Languages or One?". hindiurduflagship.org. Archived from the original on 11 March 2015. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- ↑ Hamari History, Hamari Boli

- ↑ Dua, Hans R. (1992). Hindi-Urdu as a pluricentric language. In M. G. Clyne (Ed.), Pluricentric languages: Differing norms in different nations. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-012855-1.

- ↑ Salimuddin S et al. (2013). "Oxford Urdu-English Dictionary ". Pakistan: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-597994-7 (Introduction Chapter)

- ↑ Kachru, Yamuna (2008), Braj Kachru; Yamuna Kachru; S. N. Sridhar, eds., Hindi-Urdu-Hindustani, Language in South Asia, Cambridge University Press, p. 82, ISBN 978-0-521-78653-9

- ↑ Peter Austin (1 September 2008). One thousand languages: living, endangered, and lost. University of California Press. pp. 120–. ISBN 978-0-520-25560-9. Archived from the original on 9 May 2013. Retrieved 29 December 2011.

- ↑ InpaperMagazine. "Language: Urdu and the borrowed words". dawn.com. Archived from the original on 2 July 2015. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- ↑ John R. Perry, "Lexical Areas and Semantic Fields of Arabic" in Éva Ágnes Csató, Eva Agnes Csato, Bo Isaksson, Carina Jahani, Linguistic convergence and areal diffusion: case studies from Iranian, Semitic and Turkic, Routledge, 2005. pg 97: "It is generally understood that the bulk of the Arabic vocabulary in the central, contiguous Iranian, Turkic and Indic languages was originally borrowed into literary Persian between the ninth and thirteenth centuries"

- ↑ Maldonado Garcia, Maria Isabel (2014) "Common Vocabulary in Urdu and Turkish Languages. A Case of Historical Onomasiology Archived 27 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine." Journal of Pakistan Vision. Volume 15.1. Access-date 20 March 2016

- ↑ Sigfried J. de Laet. History of Humanity: From the seventh to the sixteenth century Archived 17 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine. UNESCO, 1994. ISBN 9231028138 p 734

- ↑ "South Asian Sufis: Devotion, Deviation, and Destiny". Archived from the original on 9 February 2018. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- ↑ Faruqi, Shamsur Rahman (2003), Sheldon Pollock, ed., A Long History of Urdu Literary Culture Part 1, Literary Cultures in History: Reconstructions From South Asia, University of California Press, p. 806, ISBN 0-520-22821-9

- 1 2 3 Rahman, Tariq (2001). From Hindi to Urdu: A Social and Political History (PDF). Oxford University Press. pp. 1–22. ISBN 978-0-19-906313-0. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 October 2014.

- ↑ McGregor, Stuart (2003), "The Progress of Hindi, Part 1", Literary cultures in history: reconstructions from South Asia, p. 912, ISBN 978-0-520-22821-4 in Pollock (2003)

- ↑ Rahman, Tariq (2000). "The Teaching of Urdu in British India" (PDF). The Annual of Urdu Studies. 15: 55. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 October 2014.

- ↑ Rahman, Tariq (2014), Pakistani English (PDF), Quaid-i-Azam University=Islamabad, p. 9, archived (PDF) from the original on 22 October 2014

- ↑ "Statement – 1: Abstract of speakers' strength of languages and mother tongues – 2001". Government of India. 2001. Archived from the original on 4 April 2008. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- ↑ "Government of Pakistan: Population by Mother Tongue" (PDF). Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 October 2014.

- ↑ "Lewis, M. Paul (ed.), 2009. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Sixteenth edition. Dallas, Tex.: SIL International. Online version". Ethnologue.org. Archived from the original on 31 January 2012. Retrieved 31 January 2012.

- ↑ "Hindustani". Columbia University press. encyclopedia.com. Archived from the original on 29 July 2017.

- ↑ e.g. Gumperz (1982:20)

- ↑ Top Communications. "Holy Places — Ajmer". India Travelite. Archived from the original on 12 January 2012. Retrieved 31 January 2012.

- ↑ "Árabe y urdu aparecen entre las lenguas habituales de Catalunya, creando peligro de guetos". Europapress.es. 29 June 2009. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ↑ Rahman, Tariq (1997). "The Urdu-English Controversy in Pakistan". Modern Asian Studies: 177–207 – via National Institute of Pakistan Studies, Qu.aid-i-Az.am University.

- ↑ Schimmel, Annemarie (1992). Islam: an introduction. Albany, New York: State U of New York Press.

- ↑ Ahmad, Rizwan (2011). "Urdu in Devanagari: Shifting orthographic practices and Muslim identity in Delhi". Language in Society. doi:10.1017/s0047404511000182.

- ↑ "Government of Pakistan: Population by Mother Tongue" (PDF). Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 February 2006.

- ↑ In the lower courts in Pakistan, despite the proceedings taking place in Urdu, the documents are in English, whereas in the higher courts, i.e. the High Courts and the Supreme Court, both documents and proceedings are in English.

- ↑ Zia, Khaver (1999), "A Survey of Standardisation in Urdu". 4th Symposium on Multilingual Information Processing, (MLIT-4) Archived 6 January 2007 at the Wayback Machine., Yangon, Myanmar. CICC, Japan

- ↑ Rahman, Tariq (2010). Language Policy, Identity and Religion (PDF). Islamabad: Quaid-i-Azam University. p. 59. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 October 2014.

- ↑ Wasey, Akhtarul (16 July 2014). "50th Report of the Commissioner for Linguistic Minorities in India (July 2012 to June 2013)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2016. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- ↑ "The Constitution of Jammu and Kashmir" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 May 2012.

- ↑ "Learning In 'Urdish'". Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ↑ Yousafzai, Fawad. "Govt to launch 'Ilm Pakistan' on August 14: Ahsan". Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ↑ Mustafa, Zubeida. "Over to 'Urdish'". Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ↑ "Hindi and Urdu are classified as literary registers of the same language". Archived from the original on 2 June 2016.

- ↑ "Bringing Order to Linguistic Diversity: Language Planning in the British Raj". Language in India. Archived from the original on 26 May 2008. Retrieved 20 May 2008.

- ↑ "A Brief Hindi — Urdu FAQ". sikmirza. Archived from the original on 2 December 2007. Retrieved 20 May 2008.

- ↑ "Hindi/Urdu Language Instruction". University of California, Davis. Archived from the original on 3 January 2015. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ↑ "Ethnologue Report for Hindi". Ethnologue. Archived from the original on 1 October 2007. Retrieved 26 February 2008.

- ↑ "Urdu and its Contribution to Secular Values". South Asian Voice. Archived from the original on 11 November 2007. Retrieved 26 February 2008.

- ↑ The Annual of Urdu studies, number 11, 1996, "Some notes on Hindi and Urdu", pp. 203–208.

- ↑ Shakespear, John (1834), A dictionary, Hindustani and English, Black, Kingsbury, Parbury and Allen, archived from the original on 28 July 2017

- ↑ Fallon, S. W. (1879), A new Hindustani-English dictionary, with illustrations from Hindustani literature and folk-lore, Banāras: Printed at the Medical Hall Press, archived from the original on 11 October 2014

- ↑ "Urdu: Language of the Aam Aadmi". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 16 February 2016. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- ↑ "'Vishvas': A word that threatens Pakistan". The Express Tribune. 18 September 2012. Archived from the original on 13 October 2014. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- ↑ "Kids have it right: boundaries of Urdu and Hindi are blurred". Firstpost. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- 1 2 "Urdu Phonetic Inventory" (PDF). Center for Language Engineering. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- 1 2 Naim, C.M. (1999). Introductory Urdu (Volume One). Chicago: South Asia Language & Area Center, University of Chicago. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- ↑ Kachru (2006:20)

- ↑ Maldonado Garcia, Maria Isabel (2015). "A Corpus Based Quantitative Survey of the Persian and Arabic Elements in the Basic Vocabulary of Urdu Language" (PDF). Journal of Pakistan Vision. Pakistan Study Centre. 16 (1). Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 April 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ↑ Maldonado Garcia, Maria Isabel (2016). "A Corpus Based Quantitative Survey of the Sanskrit and Prakrit Elements in the Basic Vocabulary of Urdu Language". Pakistan Annual Research Journal. University of Peshawar. 51: 1–17.

- ↑ Colin P. Masica, The Indo-Aryan languages. Cambridge Language Surveys (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993). 466.

- ↑ "About Urdu". Afroz Taj (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill). Archived from the original on 26 February 2008. Retrieved 26 February 2008.

- ↑ India: The Last Handwritten Newspaper in the World · Global Voices Archived 1 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine.. Globalvoices.org (2012-03-26). Retrieved on 2013-07-12.

- ↑ King, 1994.

- ↑ Ahmad, R., 2006.

- ↑ "The journey within". The Hindu. 2016-03-31. Retrieved 2018-08-13.

- ↑ "Columbia University: Ghazal 36, Verse 11". Columbia.edu. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 31 January 2012.

Further reading

- Henry Blochmann (1877). English and Urdu dictionary, romanized (8 ed.). CALCUTTA: Printed at the Baptist mission press for the Calcutta school-book society. p. 215. Retrieved 6 July 2011. the University of Michigan

- John Dowson (1908). A grammar of the Urdū or Hindūstānī language (3 ed.). LONDON: K. Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co., ltd. p. 264. Retrieved 6 July 2011. the University of Michigan

- John Dowson (1872). A grammar of the Urdū or Hindūstānī language. LONDON: Trübner & Co. p. 264. Retrieved 6 July 2011. Oxford University

- John Thompson Platts (1874). A grammar of the Hindūstānī or Urdū language. Volume 6423 of Harvard College Library preservation microfilm program. LONDON: W.H. Allen. p. 399. Retrieved 6 July 2011. Oxford University

- John Thompson Platts (1892). A grammar of the Hindūstānī or Urdū language. LONDON: W.H. Allen. p. 399. Retrieved 6 July 2011. the New York Public Library

- John Thompson Platts (1884). A dictionary of Urdū, classical Hindī, and English (reprint ed.). LONDON: H. Milford. p. 1259. Retrieved 6 July 2011. Oxford University

- Ahmad, Rizwan. 2006. "Voices people write: Examining Urdu in Devanagari"

- Alam, Muzaffar. 1998. "The Pursuit of Persian: Language in Mughal Politics." In Modern Asian Studies, vol. 32, no. 2. (May, 1998), pp. 317–349.

- Asher, R. E. (Ed.). 1994. The Encyclopedia of language and linguistics. Oxford: Pergamon Press. ISBN 0-08-035943-4.

- Azad, Muhammad Husain. 2001 [1907]. Aab-e hayat (Lahore: Naval Kishor Gais Printing Works) 1907 [in Urdu]; (Delhi: Oxford University Press) 2001. [In English translation]

- Azim, Anwar. 1975. Urdu a victim of cultural genocide. In Z. Imam (Ed.), Muslims in India (p. 259).

- Bhatia, Tej K. 1996. Colloquial Hindi: The Complete Course for Beginners. London, UK & New York, NY: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-11087-4 (Book), 0415110882 (Cassettes), 0415110890 (Book & Cassette Course)

- Bhatia, Tej K. and Koul Ashok. 2000. "Colloquial Urdu: The Complete Course for Beginners." London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-13540-0 (Book); ISBN 0-415-13541-9 (cassette); ISBN 0-415-13542-7 (book and casseettes course)

- Chatterji, Suniti K. 1960. Indo-Aryan and Hindi (rev. 2nd ed.). Calcutta: Firma K.L. Mukhopadhyay.

- Dua, Hans R. 1992. "Hindi-Urdu as a pluricentric language". In M. G. Clyne (Ed.), Pluricentric languages: Differing norms in different nations. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-012855-1.

- Dua, Hans R. 1994a. Hindustani. In Asher, 1994; pp. 1554.

- Dua, Hans R. 1994b. Urdu. In Asher, 1994; pp. 4863–4864.

- Durrani, Attash, Dr. 2008. Pakistani Urdu.Islamabad: National Language Authority, Pakistan.

- Gumperz, J.J. (1982). "Discourse Strategies". Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hassan, Nazir and Omkar N. Koul 1980. Urdu Phonetic Reader. Mysore: Central Institute of Indian Languages.

- Syed Maqsud Jamil (16 June 2006). "The Literary Heritage of Urdu". Daily Star.

- Kelkar, A. R. 1968. Studies in Hindi-Urdu: Introduction and word phonology. Poona: Deccan College.

- Khan, M. H. 1969. Urdu. In T. A. Sebeok (Ed.), Current trends in linguistics (Vol. 5). The Hague: Mouton.

- King, Christopher R. 1994. One Language, Two Scripts: The Hindi Movement in Nineteenth Century North India. Bombay: Oxford University Press.

- Koul, Ashok K. 2008. Urdu Script and Vocabulary. Delhi: Indian Institute of Language Studies.

- Koul, Omkar N. 1994. Hindi Phonetic Reader. Delhi: Indian Institute of Language Studies.

- Koul, Omkar N. 2008. Modern Hindi Grammar. Springfield: Dunwoody Press.

- Narang, G. C.; Becker, D. A. (1971). "Aspiration and nasalization in the generative phonology of Hindi-Urdu". Language. 47: 646–767. doi:10.2307/412381.

- Ohala, M. 1972. Topics in Hindi-Urdu phonology. (PhD dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles).

- "A Desertful of Roses", a site about Ghalib's Urdu ghazals by Dr. Frances W. Pritchett, Professor of Modern Indic Languages at Columbia University, New York, NY, USA.

- Phukan, S. 2000. The Rustic Beloved: Ecology of Hindi in a Persianate World, The Annual of Urdu Studies, vol 15, issue 5, pp. 1–30

- The Comparative study of Urdu and Khowar. Badshah Munir Bukhari National Language Authority Pakistan 2003.

- Rai, Amrit. 1984. A house divided: The origin and development of Hindi-Hindustani. Delhi: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-561643-X.

- Snell, Rupert Teach yourself Hindi: A complete guide for beginners. Lincolnwood, IL: NTC

- Pimsleur, Dr. Paul, "Free Urdu Audio Lesson"

- The poisonous potency of script: Hindi and Urdu, ROBERT D. KING

External links

| Urdu edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

| Wikibooks has more on the topic of: Urdu |

| Wikivoyage has a phrasebook for Urdu. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Urdu. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Urdu |