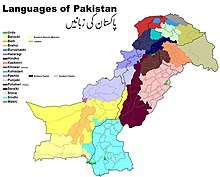

Languages of Pakistan

| Languages of Pakistan | |

|---|---|

| Official languages | English[1], Urdu |

| National languages | Urdu |

| Main languages | Punjabi (45%), Pashto (15%), Sindhi (12%), Saraiki (10%) Urdu (8%), Balochi (3.6%) |

| Main immigrant languages | Arabic, Dari, Bengali, Gujarati, Memoni |

| Sign languages | Indo-Pakistani Sign Language |

| Common keyboard layouts | |

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Pakistan |

|---|

|

| Traditions |

|

Mythology and folklore |

| Cuisine |

| Sport |

|

Monuments |

|

Pakistan is home to many dozens of languages spoken as first languages. Five languages have more than 10 million speakers each in Pakistan – Punjabi, Pashto, Sindhi, Saraiki and Urdu. Almost all of Pakistan's languages belong to the Indo-Iranian group of the Indo-European language family.

Pakistan's national language is Urdu, which, along with English, is also the official language.

The country also has several regional languages, including Punjabi, Saraiki, Pashto, Sindhi, Balochi, Kashmiri, Hindko, Brahui, Shina, Balti, Khowar, Dhatki, Marwari, Wakhi and Burushaski. Four of these are provincial languages – Punjabi, Pashto, Sindhi, and Balochi.

The number of individual languages listed for Pakistan is 74. All are living languages. Of these, 66 are indigenous and 8 are non-indigenous. Furthermore, 7 are 'institutional', 17 are 'developing', 39 are 'vigorous', 9 are 'in trouble', and 2 are 'dying'.

History

Statistics

Following are the major languages spoken in Pakistan, by number of people that speak them as their first language.

| Language | 2008 estimate | 1998 census | Areas of Predominance | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Punjabi | 76,367,360 | 44.17% | 58,433,431 | 44.15% | Punjab | |||

| 2 | Pashto | 26,692,890 | 15.44% | 20,408,621 | 15.42% | Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa | |||

| 3 | Sindhi | 24,410,910 | 14.12% | 18,661,571 | 14.10% | Rural Sindh | |||

| 4 | Saraiki | 18,019,610 | 10.42% | 13,936,594 | 10.53% | Punjab | |||

| 5 | Urdu | 13,120,540 | 7.59% | 10,019,576 | 7.57% | Urban Sindh and urban Pakistan | |||

| 6 | Balochi | 6,204,540 | 3.59% | 4,724,871 | 3.57% | Balochistan | |||

- Saraiki was included with Punjabi in 1951 and 1961 census

- Being the national language, Urdu is spoken and understood by the majority of Pakistanis and is being adopted increasingly as a first language by urbanized Pakistanis.

National language

Urdu (اردو) is the national language (قومی زبان), lingua franca and one of two official languages of Pakistan (the other currently being English). Although only about 8% of Pakistanis speak it as their first language, it is widely spoken and understood as a second language by the vast majority of Pakistanis and is being adopted increasingly as a first language by urbanized Pakistanis. It was introduced as the lingua franca upon the capitulation and annexation of Sindh (1843) and Punjab (1849) with the subsequent ban on the use of Persian. According to the linguistic historian Tariq Rahman, however, the oldest name of what is now called Urdu is Hindustani or Hindvi and it existed in some form at least from the 14th century if not earlier (Rahman 2011). It was probably the Indo-Aryan language of the area around Delhi that absorbed words of Persian, Arabic, and Chagatai (a Turkic language)—in a process like the one that created modern English. This language, according to Rahman, is the ancestor of both modern Hindi and Urdu. These became two distinct varieties when Urdu was first Persianized in the 18th century and then Hindi was Sanskritized from 1802 onwards.

The name Urdu is a short form of 'Zuban-e-Urdu-e-Mualla' i.e. language of the exalted city. In India the term Urdu, although it means 'military camp' in most Turkic languages, was used for the capital city of the king. In other words, the language of the king's capital was a Persianized form of the language known only by its previous and currently less common name Hindustani. This was shortened to 'Urdu' and this term was used for the first time in written records by the poet Mushafi in 1780 (Rahman 2011: 49). It is widely used, both formally and informally, for personal letters as well as public literature, in the literary sphere and in the popular media. It is a required subject of study in all primary and secondary schools. It is the first language of most Muhajirs (Muslim refugees who fled from different parts of India after independence of Pakistan in 1947), who form nearly 8% of Pakistan's population, and is an acquired second language for the rest. As Pakistan's national language, Urdu has been promoted to promote national unity. It is written with a modified form of the Perso-Arabic alphabet—usually in Nastaliq script.

Provincial languages

Punjabi

Punjabi (پنجابی) is spoken as a first language by more than 44% of Pakistanis, mostly in Punjab. Speakers of Saraiki and Hindko have previously been included in the Punjabi totals. The standard Punjabi variety is from the Lahore, Sialkot, Gujranwala and Sheikhupura districts and it is written in the Shahmukhi script with the Urdu alphabet.

Pashto

Pashto (پښتو) is spoken as a first language by more than 15.42% (c. 29 million) of Pakistanis, mainly in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) and in northern Balochistan as well as in ethnic Pashtun communities in the cities of Karachi, Islamabad, Rawalpindi and Lahore. Karachi is one of the most Pashto speaking cities in the world.[2] Pashto is also widely spoken in neighboring Afghanistan where it has official language status.

Pashto has rich written literary traditions as well as an oral tradition. There are three major dialect patterns within which the various individual dialects may be classified; these are Pakhto, which is the Northern (Peshawar) variety, and the softer Pashto spoken in the southern areas. Khushal Khan Khattak (1613–1689) and Rahman Baba (1633–1708) were famous poets in the Pashto language. In the last part of 20th century, Pakhto or Pashto has produced some great poets like Ghani Khan, Khatir Afridi and Amir Hamza Shinwari. They are not included in the overall percentage.

Sindhi

The Sindhi language (سنڌي) is spoken as a first language by at most 14.5% of Pakistanis, mostly in Sindh province, parts of Balochistan, Southern Punjab and Balochistan. It has a rich literature and is taught in schools. It is an Indo-Aryan (Indo-European) language, derived from Sanskrit, and influenced by Arabic languages. The Arabs ruled Sindh province for more than 150 years after Muhammad bin Qasim conquered it in 712 AD, remaining there for three years to set up Arab rule. Consequently, the social fabric of Sindh contains elements of Arabic society. Sindhi is spoken by over 53.4 million people in Pakistan and some 5.8 million in India as well as some 2.6 million in other parts of the world. It is the official language of Sindh province and is one of the scheduled languages officially recognized by the federal government in India. It is widely spoken in the Lasbela District of Balochistan (where the Lasi tribe speaks a dialect of Sindhi), many areas of the Naseerabad, Rahim Yar Khan and Dera Ghazi Khan districts in Sindh and Jafarabad districts of Balochistan, and by the Sindhi diaspora abroad. Sindhi language has six major dialects: Sireli, Vicholi, Lari, Thari, Lasi and Kachhi. It is written in the Arabic script with several additional letters to accommodate special sounds. The largest Sindhi-speaking cities are Karachi, Hyderabad, Sukkur, Shikarpur, Dadu, Jacobabad, Larkana and Nawabshah. Sindhi literature is also spiritual in nature. Shah Abdul Latif Bhita'i (1689–1752) is one of its greatest poets; he wrote the famous poetic compendium Shah Jo Risalo which includes the folk stories "Sassi Punnun" and "Umar Marvi".

Balochi

Balochi (بلوچی) is spoken as a first language by about 4% of Pakistanis, mostly in Balochistan province. Rakshani is the major dialect group in terms of numbers. Sarhaddi is a sub-dialect of Rakshani. Other sub-dialects are Kalati (Qalati), Chagai-Kharani and Panjguri. Eastern Hill Balochi or Northern Balochi is very different from the rest. The name Balochi or Baluchi is not found before the 10th Century. It is one of the 9 distinguished languages of Pakistan. Since Balochi is a very poetic and rich language and has a certain degree of affinity to Urdu, Balochi poets tend to be very good poets in Urdu as well and Ata Shaad, Gul Khan Nasir and Noon Meem Danish are excellent examples of this.

Sub-provincial regional languages

Saraiki

Saraiki (Sarā'īkī, also spelt Siraiki, or less often Seraiki) is an Indo-Aryan language of the Lahnda group, spoken in the south-western half of the province of Punjab. Saraiki is to a high degree mutually intelligible with Standard Punjabi and shares with it a large portion of its vocabulary and morphology. At the same time in its phonology it is radically different (particularly in the lack of tones, the preservation of the voiced aspirates and the development of implosive consonants), and has important grammatical features in common with the Sindhi language spoken to the south. Saraiki is the first language of about 20 million people in Pakistan, its territory ranges across southern Punjab, parts of southern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, and some border regions of northern Sindh and eastern Balochistan.

Brahui

Brahui (براھوی) is a Dravidian language of central and east-central Balochistan. The language has been influenced by neighboring Balochi and to a lesser extent by Sindhi and Pashto. 1% of the Pakistani population has Brahui as their first language. It is one of the nine distinguished languages of Pakistan. The Brahui people have traditionally been taken as a relict population, suggesting that Dravidian languages were formerly more widespread but were supplanted by the incoming Indo-Aryan languages.[3] However, this idea has fallen out of favor; Brahui appears to have migrated to Balochistan from central India after 1000 CE, as evidenced by the absence of Avestan loanwords. The main Iranian contributor to Brahui vocabulary, Balochi, is a western Iranian language like Kurdish that moved to the area from the west only around 1000 CE.[4]

Shina

Shina (شینا) (also known as Tshina) is a Dardic language spoken by a plurality of people in Gilgit–Baltistan of Pakistan. The valleys in which it is spoken include Astore, Chilas, Dareil, Tangeer, Gilgit, Ghizer, and a few parts of Kohistan. It is also spoken in the Gurez, Drass, Kargil, Karkit Badgam and Ladakh valleys of Kashmir. There were 321,000 speakers of Gilgiti Shina in 1981. The current estimate is nearly 600,000 people.

Kashmiri

Kashmiri (كأشُر) is a Dardic language spoken in Azad Kashmir, about 124,000 speakers[5] (or 2% of the Azad Kashmir population).

Other languages

English (previous colonial and co-official language)

English is a co-official language of Pakistan and is widely used in the executive, legislative and judicial branches as well as to some extent in the officer ranks of Pakistan's armed forces. Pakistan's Constitution and laws were written in English and are now being re-written in the local languages. It is also widely used in schools, colleges and universities as a medium of instruction. English is seen as the language of upward mobility, and its use is becoming more prevalent in upper social circles, where it is often spoken alongside native Pakistani languages. In 2015, it was announced that there were plans to promote Urdu in official business, but Pakistan's Minister of Planning Ahsan Iqbal stated,"Urdu will be a second medium of language and all official business will be bilingual." He also went on to say that English would be taught alongside Urdu in schools.[6]

Arabic (historical official language, religious and minor literary language)

In the history, Arabic (عربي) was the official language when the territory of the modern state Islamic Republic of Pakistan was a part of the Umayyad Caliphate between 651 and 750.

The Arabic language is mentioned in the constitution of Pakistan. It declares in article 31 No. 2 that "The State shall endeavour, as respects the Muslims of Pakistan (a) to make the teaching of the Holy Quran and Islamiat compulsory, to encourage and facilitate the learning of Arabic language ..."[7]

Arabic is the religious language of Muslims. The Quran, Sunnah, Hadith and Muslim theology is taught in Arabic with Urdu translation. The Pakistani diaspora living in the Middle East has further increased the number of people who can speak Arabic in Pakistan. Arabic is taught as a religious language in mosques, schools, colleges, universities and madrassahs. A majority of Pakistan's Muslim population has had some form of formal or informal education in the reading, writing and pronunciation of the Arabic language as part of their religious education.

The National Education Policy 2017 declares in article 3.7.4 that: “Arabic as compulsory part will be integrated in Islamiyat from Middle to Higher Secondary level to enable the students to understand the Holy Quran.“ Furthermore, it specifies in article 3.7.6: “Arabic as elective subject shall be offered properly at Secondary and Higher Secondary level with Arabic literature and grammar in its course to enable the learners to have command in the language.“ This law is also valid for private schools as it defines in article 3.7.12: “The curriculum in Islamiyat, Arabic and Moral Education of public sector will be adopted by the private institutions to make uniformity in the society.“[8]

Persian (previous colonial and literary language)

Persian (فارسی) was the official and cultural language of the Mughal Empire, a continuation since the introduction of the language by Central Asian Turkic invaders who migrated into the Indian Subcontinent,[9] and the patronisation of it by the earlier Turko-Persian Delhi Sultanate. Persian was officially abolished with the arrival of the British: in Sindh in 1843 and in Punjab in 1849. It is today spoken primarily by the Dari speaking refugees from Afghanistan and the Hazara community of Quetta.

Bengali

Bengali (بنگالی) is not an official language in Pakistan, but a significant number of Pakistani citizens have migrated from East Bengal and live in West Pakistan or East Pakistan prior to 1971. Others include illegal immigrants who migrated from Bangladesh after 1971. Most Pakistani Bengalis, are bilingual speaking both Urdu and Bengali, and are mainly settled in Karachi.

Turkic languages (previous colonial and immigrant languages)

Turkic languages were used by the ruling Turco-Mongols such as the Mughals and earlier Sultans of the subcontinent. There are small pockets of Turkic speakers found throughout the country, notably in the valleys in the countries northern regions which lie adjacent to Central Asia, western Pakistani region of Waziristan principally around Kanigoram where the Burki tribe dwells and in Pakistan's urban centres of Karachi, Lahore and Islamabad. The autobiography of Mughal emperor Babur, Tuzk Babari was also written in Turkish. After returning from exile in Safavid Persia in 1555, Mughal emperor Humayun further introduced Persian language and culture in the court and government. The Chaghatai language, in which Babur had written his memoirs, disappeared almost entirely from the culture of the courtly elite, and Mughal emperor Akbar could not speak it. Later in life, Humayun himself is said to have spoken in Persian verse more often than not.

A number of Turkic speaking refugees, mostly Uzbeks and Turkmens from Afghanistan and Uyghurs from China have settled in Pakistan.

Minor languages

Other languages spoken by linguistic minorities include the languages listed below, with speakers ranging from a few hundred to tens of thousands. A few are highly endangered languages that may soon have no speakers at all.[10]

- Aer

- Badeshi

- Bagri/Vagri

- Balti

- Bateri

- Bhaya

- Brahui

- Brokskat

- Burig/Purik

- Burushaski

- Changthang

- Chilisso

- Chitrali

- Dari

- Dameli

- Dogri

- Dehawri

- Dhatki/Thari

- Domaaki

- Gawar-Bati

- Ghera

- Goaria

- Gowro

- Gujarati

- Gojri (Gujari)

- Gurgula

- Hazaragi

- Hindko

- Jadgali

- Jandavra

- Jogi, a language spoken by Jogi

- Kabutra

- Kachchi/Kutchi

- Kalami

- Kalasha-mun

- Kalkoti

- Kamviri

- Kati

- Khetrani

- Khowar

- Kohistani Indus

- Koli-Kachi

- Koli-Parkari

- Koli-Wadiyara

- Lasi

- Loarki

- Marwari

- Memoni

- Od/Odki

- Ormuri

- Palula

- Pothowari

- Sansi

- Torwali

- Uyghur (spoken by Uyghur community)

- Ushojo/Ushoji

- Wakhi

- Waneci

- Yidgha

- Zangskari

Classification

The Indo-Iranian languages derive from a reconstructed common proto-language, called Proto-Indo-Iranian.

Indo-Iranian

Most of the languages of Pakistan belong to the Indo-Iranian (more commonly known as Indo-Iranic[11]) branch of the Indo-European language family.[12][13] They are divided between two or three major groups: Indo-Aryan (the majority, including Urdu, Punjabi, Sindhi, Hindko, and Saraiki, among others), Iranian (or Iranic[14]) (the major ones being Pashto, Balochi, and Khowar, among others) and Dardic (the major one being Kashmiri). At times Dardic is considered another branch of Indo-Iranian, but many linguists term Dardic as individual Indo-Aryan languages that do not form any subgrouping within Indo-Aryan.[15] The Nuristani language, considered another individual branch of Indo-Iranian, is spoken by the Nuristani minority in Afghanistan near the Afghan-Pakistani border, but not known to be spoken indigenously in Pakistan.

Some of the important languages in the Indo-Aryan group are dialect continuums. One of these is Lahnda,[16] and includes Western Punjabi (but not standard Punjabi), Northern Hindko, Southern Hindko, Khetrani, Saraiki, and Pahari-Potwari, plus two more languages outside of Pakistan. The other is Marwari, and includes Marwari of Pakistan and several languages of India (Dhundari, Marwari, Merwari, Mewari, and Shekhawati).[17] A third is Rajasthani, and consists of Bagri, Gujari in Pakistan and several others in India: Gade Lohar,[18] Harauti (Hadothi), Malvi, and Wagdi.

Although Urdu is not a dialect continuum, it is a major dialect of Hindustani and somewhat differs from Hindi, another dialect of Hindustani which is not spoken in Pakistan.

There are several dialects continuums in the Iranian group as well: Balochi, which includes Eastern, Western and Southern Balochi;[19] and Pashto, and includes Northern, Central, and Southern Pashto.[20]

Other

The following three languages of Pakistan are not part of the Indo-European language family:

- Brahui (spoken in central Balochistan province) is a Dravidian language. Its vocabulary has been significantly influenced by Balochi. It is an individual language in the Dravidian language family and does not belong to any subgrouping in that language family.

- The Balti dialect of Ladakhi (spoken in an area of southern Gilgit–Baltistan) is a Tibetan language of the Tibeto-Burman language family[21]

- Burushaski (spoken in Hunza, Nagar, Yasin, and Ishkoman valleys in Gilgit–Baltistan) is a language isolate with no indiginious written script and instead currently uses Urdu script, based on the Perso-Arabic script.

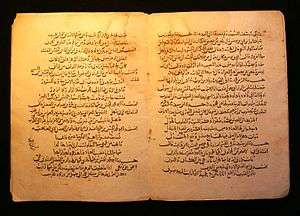

Writing systems

All languages of Pakistan, besides English, are written in Nastaʿlīq, a modified Perso-Arabic script. The Mughal Empire adopted Persian as the court language during their rule over South Asia as did their predecessors, such as the Ghaznavids. During this time, Nastaʿlīq came into widespread use in South Asia. The influence remains to this day. In Pakistan, almost everything in Urdu is written in the script, concentrating the greater part of Nastaʿlīq usage in the world.

The Urdu alphabet is the right-to-left alphabet. It is a modification of the Persian alphabet, which is itself a derivative of the Arabic alphabet. With 38 letters, the Urdu alphabet is typically written in the calligraphic Nasta'liq script, whereas Arabic is more commonly in the Naskh style.

Sindhi adopted a variant of the Persian alphabet as well, in the 19th century. The script is used in Pakistan today. It has a total of 52 letters, augmenting the Urdu with digraphs and eighteen new letters (ڄ ٺ ٽ ٿ ڀ ٻ ڙ ڍ ڊ ڏ ڌ ڇ ڃ ڦ ڻ ڱ ڳ ڪ) for sounds particular to Sindhi and other Indo-Aryan languages. Some letters that are distinguished in Arabic or Persian are homophones in Sindhi.

Balochi and Pashto are written in Perso-Arabic script. The Shahmukhī script, a variant of the Urdu alphabet, is used to write the Punjabi language in Pakistan.

Usually, bare transliterations of Urdu into Roman letters, Roman Urdu, omit many phonemic elements that have no equivalent in English or other languages commonly written in the Latin script. The National Language Authority of Pakistan has developed a number of systems with specific notations to signify non-English sounds, but these can only be properly read by someone already familiar with Urdu.

See also

References

- ↑ "Article: 251 National language". Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- ↑ "Demographic divide". Zia Ur Rehman, a journalist and a researcher based in Karachi. thefridaytimes. July 15–21, 2011. Retrieved 2013-01-05.

- ↑ (Mallory 1989)

- ↑ J. H. Elfenbein, A periplous of the ‘Brahui problem’, Studia Iranica vol. 16 (1987), pp. 215-233.

- ↑ "Pakistan". Ethnologue.

- ↑ "Pakistan to replace English with Urdu as official language - The Express Tribune". The Express Tribune. Retrieved 2016-01-05.

- ↑ Constitution of Pakistan: Constitution of Pakistan, 1973 - Article: 31 Islamic way of life, 1973, retrieved 28 July 2018

- ↑ Ministry of Federal Education and Professional Training: National Education Policy 2017, p. 25, retrieved 28 July 2018

- ↑ "South Asian Sufis: Devotion, Deviation, and Destiny". Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- ↑ Gordon, Raymond (2005). "Languages of Pakistan". Missing or empty

|url=(help);|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ Dwyer, Arienne M. "The texture of tongues: Languages and power in China." Nationalism and Ethnic Politics 4.1-2 (1998): 68-85.

- ↑ Marian Rengel Pakistan: A Primary Source Cultural Guide page 38 ISBN 0823940012, 9780823940011

- ↑ Mukhtar Ahmed Ancient Pakistan - an Archaeological History pages 6-7 ISBN 1495966437, 9781495966439

- ↑ Yagmur, Kutlay. "Languages in Turkey." MULTILINGUAL MATTERS (2001): 407-428.

- ↑ Concise Encyclopedia of Languages of the World (page 283)

- ↑ ISO 639 code sets. Sil.org. Retrieved on 2011-01-14.

- ↑ ISO 639 code sets. Sil.org. Retrieved on 2011-01-14.

- ↑ Ethnologue report for language code: gda. Ethnologue.com. Retrieved on 2011-01-14.

- ↑ ISO 639 code sets. Sil.org. Retrieved on 2011-01-14.

- ↑ ISO 639 code sets. Sil.org. Retrieved on 2011-01-14.

- ↑ WALS – Sino-Tibetan. Wals.info. Retrieved on 2011-01-14

Bibliography

- Rahman, Tariq (1996) Language and Politics of Pakistan Karachi: Oxford University Press. New Delhi: Orient Blackswan, 2007.

- Rahman, Tariq (2002) Language, Ideology and Power: Language-learning among the Muslims of Pakistan and North India Karachi: Oxford University Press. Rev.ed. New Delhi: Orient Blackswan, 2008.

- Rahman, Tariq (2011) From Hindi to Urdu: A Social and Political History Karachi: Oxford University Press.

External links

- Linguistic map of Pakistan at Muturzikin.com

- Pakistan census statistics by population

- List of Pakistani Languages at Ethnologue