Madison, Wisconsin

| Madison, Wisconsin | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| State capital and city | |||

| |||

| |||

| Nickname(s): Madtown, Mad City, "The City of Four Lakes" | |||

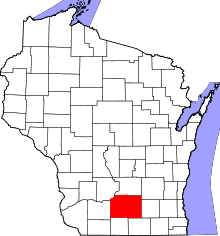

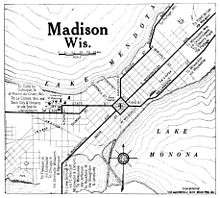

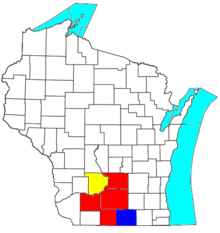

Location of Madison in Dane County, Wisconsin. | |||

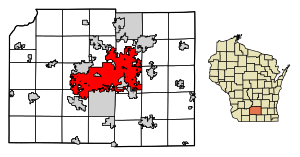

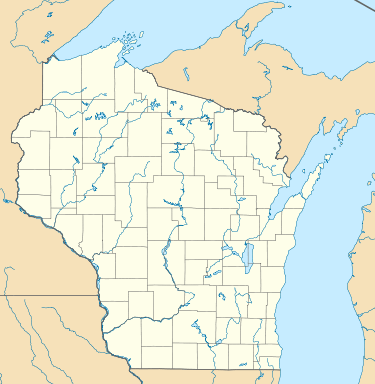

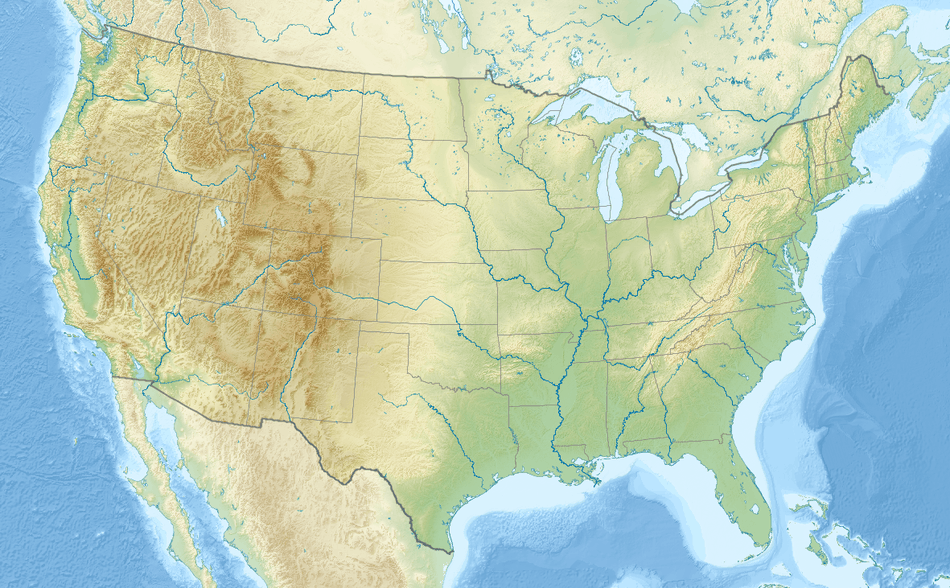

Madison, Wisconsin Location in Wisconsin, United States & North America  Madison, Wisconsin Madison, Wisconsin (the US)  Madison, Wisconsin Madison, Wisconsin (North America) | |||

| Coordinates: 43°4′N 89°24′W / 43.067°N 89.400°WCoordinates: 43°4′N 89°24′W / 43.067°N 89.400°W | |||

| Country | United States | ||

| State | Wisconsin | ||

| County | Dane | ||

| Municipality | City | ||

| Incorporated | 1848 | ||

| Named for | James Madison | ||

| Government | |||

| • Mayor | Paul Soglin (D) | ||

| Area[1] | |||

| • City | 94.03 sq mi (243.54 km2) | ||

| • Land | 76.79 sq mi (198.89 km2) | ||

| • Water | 17.24 sq mi (44.65 km2) | ||

| Elevation | 873 ft (226 m) | ||

| Population (2010)[2] | |||

| • City | 233,209 | ||

| • Estimate (2017)[3] | 255,214 | ||

| • Rank | US: 82nd | ||

| • Density | 3,037.0/sq mi (1,172.6/km2) | ||

| • Urban | 329,533 1 (US: 93rd) | ||

| • Metro | 605,435 (US: 86th) | ||

| • Demonym | Madisonian | ||

| Time zone | UTC−6 (Central) | ||

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) | ||

| Area code | 608 | ||

| FIPS code | 55-48000 | ||

| Website |

cityofmadison | ||

| 1 Urban = 2010 Census | |||

Madison is the capital of the U.S. state of Wisconsin and the seat of Dane County. As of July 1, 2017, Madison's estimated population of 255,214[4] made it the second-largest city in Wisconsin, after Milwaukee, and the 82nd-largest in the United States. The city forms the core of the United States Census Bureau's Madison Metropolitan Statistical Area, which includes Dane County and neighboring Iowa, Green, and Columbia counties. The Madison Metropolitan Statistical Area's 2010 population was 568,593.

Founded in 1829 on an isthmus between Lake Monona and Lake Mendota, Madison was named the capital of the Wisconsin Territory in 1836 and became the capital of the state of Wisconsin when it was admitted to the Union in 1848. That same year, the University of Wisconsin was founded in Madison and the state government and university have become the city's two largest employers.[5] The city is also known for its lakes, restaurants, and extensive network of parks and bike trails, with much of the park system designed by landscape architect John Nolen.

Since the 1960s, Madison has been a center of political liberalism.[6] Though Wisconsin is regarded as a "battleground" or "swing" state in elections,[7] Madison and Dane County have supported every Democratic Party presidential nominee since John F. Kennedy in 1960, with the party's most recent nominees, Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton, carrying Dane County with over 70 per cent of the vote in 2008, 2012, and 2016.[8]

History

Madison's origins begin in 1829, when former federal judge James Duane Doty purchased over a thousand acres (4 km²) of swamp and forest land on the isthmus between Lakes Mendota and Monona, with the intention of building a city in the Four Lakes region. He purchased 1,261 acres for $1,500. When the Wisconsin Territory was created in 1836 the territorial legislature convened in Belmont, Wisconsin. One of the legislature's tasks was to select a permanent location for the territory's capital. Doty lobbied aggressively for Madison as the new capital, offering buffalo robes to the freezing legislators and promising choice Madison lots at discount prices to undecided voters.[9] He had James Slaughter plat two cities in the area, Madison and "The City of Four Lakes", near present-day Middleton.

Doty named the city Madison for James Madison, the fourth President of the U.S. who had died on June 28, 1836, and he named the streets for the other 39 signers of the U.S. Constitution.[10] Although the city existed only on paper, the territorial legislature voted on November 28 in favor of Madison as its capital, largely because of its location halfway between the new and growing cities around Milwaukee in the east and the long established strategic post of Prairie du Chien in the west, and between the highly populated lead mining regions in the southwest and Wisconsin's oldest city, Green Bay, in the northeast. Being named for the much-admired founding father James Madison, who had just died, and having streets named for each of the 39 signers of the Constitution, may have also helped attract votes.[11]

Creation and expansion

The cornerstone for the Wisconsin capitol was laid in 1837, and the legislature first met there in 1838. On October 9, 1839, Kintzing Prichett registered the plat of Madison at the registrar's office of the then-territorial Dane County.[12] Madison was incorporated as a village in 1846, with a population of 626. When Wisconsin became a state in 1848, Madison remained the capital, and the following year it became the site of the University of Wisconsin (now University of Wisconsin–Madison). The Milwaukee & Mississippi Railroad (a predecessor of the Milwaukee Road) connected to Madison in 1854. Madison incorporated as a city in 1856, with a population of 6,863, leaving the unincorporated remainder as a separate Town of Madison.[13] The original capitol was replaced in 1863 and the second capitol burned in 1904. The current capitol was built between 1906 and 1917.[14]

During the Civil War, Madison served as a center of the Union Army in Wisconsin. The intersection of Milwaukee, East Washington, Winnebago, and North Streets is known as Union Corners, because a tavern there was the last stop for Union soldiers before heading to fight the Confederates. Camp Randall, on the west side of Madison, was built and used as a training camp, a military hospital, and a prison camp for captured Confederate soldiers. After the war ended, the Camp Randall site was absorbed into the University of Wisconsin and Camp Randall Stadium was built there in 1917. In 2004 the last vestige of active military training on the site was removed when the stadium renovation replaced a firing range used for ROTC training.

The City of Madison continued annexations from the Town of Madison almost from the date of the city's incorporation, leaving the latter a collection of discontiguous areas subject to annexation. In the wake of continued controversy and an effort in the state legislature to simply abolish the town, an agreement was reached in 2003 to provide for the incorporation of the remaining portions of the Town into the City of Madison and the City of Fitchburg by October 30, 2022.[15]

Geography

Madison is located in the center of Dane County in south-central Wisconsin, 77 miles (124 km) west of Milwaukee and 122 miles (196 km) northwest of Chicago. The city completely surrounds the smaller Town of Madison, the City of Monona, and the villages of Maple Bluff and Shorewood Hills. Madison shares borders with its largest suburb, Sun Prairie, and three other suburbs, Middleton, McFarland, and Fitchburg. The city's boundaries also approach the city of Verona and the villages of Cottage Grove, DeForest, and Waunakee.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 94.03 square miles (243.54 km2), of which 76.79 square miles (198.89 km2) is land and 17.24 square miles (44.65 km2) is water.[1]

The city is sometimes described as The City of Four Lakes, comprising the four successive lakes of the Yahara River: Lake Mendota ("Fourth Lake"), Lake Monona ("Third Lake"), Lake Waubesa ("Second Lake") and Lake Kegonsa ("First Lake"),[16] although Waubesa and Kegonsa are not actually in Madison, but just south of it. A fifth smaller lake, Lake Wingra, is within the city as well; it is connected to the Yahara River chain by Wingra Creek. The Yahara flows into the Rock River, which flows into the Mississippi River. Downtown Madison is located on an isthmus between Lakes Mendota and Monona. The city's trademark of "Lake, City, Lake" reflects this geography.

Local identity varies throughout Madison, with over 120 officially recognized neighborhood associations, such as the east side Williamson-Marquette Neighborhood.[17][18] Neighborhoods on and near the eastern part of the isthmus, some of the city's oldest, have the strongest sense of identity and are the most politically liberal. Historically, the north, east, and south sides were blue collar while the west side was white collar, and to a certain extent this remains true. Students dominate on the University of Wisconsin campus and to the east into downtown, while to its south and in Shorewood Hills on its west, faculty have been a major presence since those neighborhoods were originally developed. The turning point in Madison's development was the university's 1954 decision to develop its experimental farm on the western edge of town; since then, the city has grown substantially along suburban lines.

Climate

Madison, along with the rest of the state, has a humid continental climate (Köppen: Dfb/Dfa), characterized by variable weather patterns and a large seasonal temperature variance: winter temperatures can be well below freezing, with moderate to occasionally heavy snowfall and temperatures reaching 0 °F (−18 °C) on 17 nights annually; high temperatures in summer average in the lower 80s °F (27–28 °C), reaching 90 °F (32 °C) on an average 12 days per year,[19] with lower humidity levels than winter but higher than spring. Summer accounts for a greater proportion of annual rainfall, but winter still sees significant precipitation.

| Climate data for Madison, Wisconsin (KMSN), 1981–2010 normals,[lower-alpha 1] extremes 1869–present[lower-alpha 2] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 58 (14) |

68 (20) |

83 (28) |

94 (34) |

101 (38) |

101 (38) |

107 (42) |

102 (39) |

99 (37) |

90 (32) |

77 (25) |

65 (18) |

107 (42) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 45.5 (7.5) |

51.1 (10.6) |

69.1 (20.6) |

79.6 (26.4) |

84.4 (29.1) |

90.9 (32.7) |

92.3 (33.5) |

91.1 (32.8) |

87.0 (30.6) |

78.5 (25.8) |

64.3 (17.9) |

49.0 (9.4) |

94.3 (34.6) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 26.4 (−3.1) |

31.1 (−0.5) |

43.1 (6.2) |

57.3 (14.1) |

68.4 (20.2) |

77.9 (25.5) |

81.6 (27.6) |

79.4 (26.3) |

71.8 (22.1) |

58.9 (14.9) |

44.1 (6.7) |

30.2 (−1) |

56.0 (13.3) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 11.1 (−11.6) |

15.1 (−9.4) |

24.8 (−4) |

35.8 (2.1) |

46.1 (7.8) |

56.1 (13.4) |

61.0 (16.1) |

59.0 (15) |

50.2 (10.1) |

38.8 (3.8) |

28.2 (−2.1) |

15.9 (−8.9) |

36.9 (2.7) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | −11.5 (−24.2) |

−6.6 (−21.4) |

5.0 (−15) |

19.8 (−6.8) |

31.0 (−0.6) |

41.4 (5.2) |

48.2 (9) |

46.3 (7.9) |

33.9 (1.1) |

24.0 (−4.4) |

11.8 (−11.2) |

−5.7 (−20.9) |

−15.7 (−26.5) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −37 (−38) |

−29 (−34) |

−29 (−34) |

0 (−18) |

19 (−7) |

31 (−1) |

36 (2) |

35 (2) |

25 (−4) |

12 (−11) |

−14 (−26) |

−28 (−33) |

−37 (−38) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 1.23 (31.2) |

1.45 (36.8) |

2.20 (55.9) |

3.40 (86.4) |

3.55 (90.2) |

4.54 (115.3) |

4.18 (106.2) |

4.27 (108.5) |

3.13 (79.5) |

2.40 (61) |

2.39 (60.7) |

1.74 (44.2) |

34.48 (875.8) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 12.9 (32.8) |

10.6 (26.9) |

7.0 (17.8) |

2.6 (6.6) |

0.2 (0.5) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.5 (1.3) |

3.6 (9.1) |

13.5 (34.3) |

50.9 (129.3) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 10.2 | 9.2 | 10.5 | 12.1 | 11.9 | 11.1 | 10.6 | 9.4 | 9.3 | 9.8 | 10.6 | 10.1 | 124.8 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 9.8 | 7.9 | 5.8 | 2.0 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 3.8 | 8.7 | 38.7 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 74.5 | 73.1 | 71.4 | 66.3 | 65.8 | 68.3 | 71.0 | 74.4 | 76.8 | 73.2 | 76.9 | 78.5 | 72.5 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 143.0 | 152.3 | 187.3 | 206.7 | 263.1 | 293.1 | 304.9 | 270.2 | 213.8 | 172.5 | 111.4 | 109.5 | 2,427.8 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 49 | 52 | 51 | 51 | 58 | 64 | 66 | 63 | 57 | 50 | 38 | 39 | 54 |

| Source: NOAA (relative humidity and sun 1961–1990),[19][20][21] The Weather Channel[22] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1840 | 172 | — | |

| 1850 | 1,525 | 786.6% | |

| 1860 | 6,611 | 333.5% | |

| 1870 | 9,176 | 38.8% | |

| 1880 | 10,324 | 12.5% | |

| 1890 | 13,426 | 30.0% | |

| 1900 | 19,164 | 42.7% | |

| 1910 | 25,531 | 33.2% | |

| 1920 | 38,378 | 50.3% | |

| 1930 | 57,899 | 50.9% | |

| 1940 | 67,447 | 16.5% | |

| 1950 | 96,056 | 42.4% | |

| 1960 | 126,706 | 31.9% | |

| 1970 | 171,809 | 35.6% | |

| 1980 | 170,616 | −0.7% | |

| 1990 | 191,262 | 12.1% | |

| 2000 | 208,054 | 8.8% | |

| 2010 | 233,209 | 12.1% | |

| Est. 2017 | 255,214 | [3] | 9.4% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[23] | |||

As of 2000 the median income for a household in the city was $41,941, and the median income for a family was $59,840. Males had a median income of $36,718 versus $30,551 for females. The per capita income for the city was $23,498. About 5.8% of families and 15.0% of the population were below the poverty line, including 11.4% of those under age 18 and 4.5% of those age 65 or over.

2010 census

As of the census[2] of 2010, there were 233,209 people, 102,516 households, and 47,824 families residing in the city. The population density was 3,037.0 inhabitants per square mile (1,172.6/km2). There were 108,843 housing units at an average density of 1,417.4 per square mile (547.3/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 78.9% White, 7.3% African American, 0.4% Native American, 7.4% Asian, 2.9% from other races, and 3.1% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 6.8% of the population.

There were 102,516 households of which 22.2% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 35.1% were married couples living together, 8.4% had a female householder with no husband present, 3.2% had a male householder with no wife present, and 53.3% were non-families. 36.2% of all households were made up of individuals and 7.5% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.17 and the average family size was 2.87.

The median age in the city was 30.9 years. 17.5% of residents were under the age of 18; 19.6% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 31.4% were from 25 to 44; 21.9% were from 45 to 64; and 9.6% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 49.2% male and 50.8% female.

Combined Statistical Area

Madison is the larger principal city of the Madison-Janesville-Beloit, WI CSA, a Combined Statistical Area that includes the Madison metropolitan area (Columbia, Dane, Green and Iowa counties), the Janesville-Beloit metropolitan area (Rock County), and the Baraboo micropolitan area (Sauk County).[24][25][26] As of July 1, 2016, the Madison MSA had an estimated population of 648,929[27] and the Madison CSA had an estimated population of 874,498.[28]

Religion

Madison is the episcopal see for the Roman Catholic Diocese of Madison.[29] Saint Raphael's Cathedral, damaged by arson in 2005 and demolished in 2008, was the mother church of the diocese. The steeple and spire survived and have been preserved with the intention they could be incorporated in the structure of a replacement building.[30]

The USA's third largest congregation of Unitarian Universalists,[31] the First Unitarian Society of Madison, makes its home in the historic Unitarian Meeting House, designed by one of its members, Frank Lloyd Wright.[32]

InterVarsity Christian Fellowship/USA has its headquarters in Madison. Most American Christian movements are represented in the city, including mainline denominations, evangelical, charismatic and fully independent churches, including an LDS stake. The city also has multiple Sikhism temples, Hindu temples, three mosques and several synagogues, a Bahá'í community center, a Quaker Meeting House, and a Unity Church congregation.

Economy

Wisconsin state government and the University of Wisconsin–Madison remain the two largest Madison employers. However, Madison's economy today is evolving from a government-based economy to a consumer services and high-tech base, particularly in the health, biotech, and advertising sectors. Beginning in the early 1990s, the city experienced a steady economic boom and has been less affected by recession than other areas of the state. Much of the expansion has occurred on the city's south and west sides, but it has also affected the east side near the Interstate 39-90-94 interchange and along the northern shore of Lake Mendota. Underpinning the boom is the development of high-tech companies, many fostered by UW–Madison working with local businesses and entrepreneurs to transfer the results of academic research into real-world applications, especially bio-tech applications.

Many businesses are attracted to Madison's skill base, taking advantage of the area's high level of education. 48.2% of Madison's population over the age of 25 holds at least a bachelor's degree.[33] Forbes magazine reported in 2004 that Madison has the highest percentage of individuals holding Ph.D.s in the United States. In 2006, the same magazine listed Madison as number 31 in the top 200 metro areas for "Best Places for Business and Careers."[34] Madison has also been named in Forbes ten Best Cities several times within the past decade.[35][36][37][38] In 2009, in the midst of the late-2000s recession, Madison had an unemployment rate of 3.5% and was ranked number one in a list of "ten cities for job growth".[39]

Business

The largest employer in Madison is the Wisconsin state government, excluding employees of the University of Wisconsin–Madison, and University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinics employees, although both groups of workers are state employees.[40]

The University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinics is an important regional teaching hospital and regional trauma center, with strengths in transplant medicine, oncology, digestive disorders, and endocrinology.[41] Other Madison hospitals include St. Mary's Hospital,[42] Meriter Hospital, and the VA Medical Center.

Madison is home to companies such as Spectrum Brands (formerly Rayovac), Alliant Energy, the Credit Union National Association (CUNA), MGE Energy, Aprilaire, and Sub-Zero & Wolf Appliance. Insurance companies based in Madison include American Family Insurance, CUNA Mutual Group, and National Guardian Life.

Technology companies in Madison include Google, Microsoft,[43] Broadjam, a regional office of CDW, Full Compass Systems, Raven Software, and TDS Telecom. Biotech firms include Panvera (now part of Invitrogen). The contract research organization Covance is a major employer in the city.[44] Madison's community hackerspaces/makerspaces are Sector67, which serves inventors and entrepreneurs, and The Bodgery, which serves hobbyists, artists, and tinkerers. Epic Systems was based in Madison from 1979 to 2005, when it moved to a larger campus in nearby Verona. Other firms include Nordic, Forward Health, and Forte Research Systems.[45]

Oscar Mayer was a Madison fixture for decades, and was a family business for many years before being sold to Kraft Foods. The Onion satirical newspaper, as well as the pizza chains Rocky Rococo and the Glass Nickel Pizza Company, originated in Madison.[46][47]

Culture

In 1996 Money magazine identified Madison as the best place to live in the United States.[48] It has consistently ranked near the top of the best-places list in subsequent years, with the city's low unemployment rate a major contributor.

The main downtown thoroughfare is State Street, which links the University of Wisconsin campus with the Capitol Square, and is lined with restaurants, espresso cafes, and shops. Only pedestrians, buses, emergency vehicles, delivery vehicles, and bikes are allowed on State Street.

On Saturday mornings in the summer, the Dane County Farmers' Market is held around the Capitol Square, the largest producer-only farmers' market in the country.[49] This market attracts numerous vendors who sell fresh produce, meat, cheese, and other products. On Wednesday evenings, the Wisconsin Chamber Orchestra performs free concerts on the capitol's lawn.[50]

The Great Taste of the Midwest craft beer festival, established in 1987 and the second-longest-running such event in North America, is held the second Saturday in August. The highly coveted tickets sell out within an hour of going on sale in May.[51]

Madison was host to Rhythm and Booms, a massive fireworks celebration coordinated to music. It began with a fly-over by F-16s from the local Wisconsin Air National Guard. This celebration was the largest fireworks display in the Midwest in length, number of shells fired, and the size of its annual budget.[52] Effective 2015, the event location was changed to downtown and renamed Shake The Lake.[53][54]

During the winter months, sports enthusiasts enjoy ice-boating, ice skating, ice hockey, ice fishing, cross-country skiing, and snowkiting.[55] During the rest of the year, outdoor recreation includes sailing on the local lakes, bicycling, and hiking.

Madison was named the number one college sports town by Sports Illustrated in 2003.[56] In 2004 it was named the healthiest city in the United States by Men's Journal magazine. Many major streets in Madison have designated bike lanes and the city has one of the most extensive bike trail systems in the nation.[57]

There are many cooperative organizations in the Madison area, ranging from grocery stores (such as the Willy Street Cooperative) to housing co-ops (such as Madison Community Cooperative and Nottingham Housing Cooperative) to worker cooperatives (including an engineering firm, a wholesale organic bakery and a cab company).

In 2005, Madison was included in Gregory A. Kompes' book, 50 Fabulous Gay-Friendly Places to Live.[58] The Madison metro area has a higher percentage of gay couples than any other city in the area outside of Chicago and Minneapolis.[59]

Among the city's neighborhood fairs and celebrations are two large student-driven gatherings, the Mifflin Street Block Party and the State Street Halloween Party. Rioting and vandalism at the State Street gathering in 2004 and 2005 led the city to institute a cover charge for the 2006 celebration.[60] In an attempt to give the event more structure and to eliminate vandalism, the city and student organizations worked together to schedule performances by bands, and to organize activities. The event has been named "Freakfest on State Street."[61] Events such as these have helped contribute to the city's nickname of "Madtown."

In 2009, the Madison Common Council voted to name the plastic pink flamingo as the official city bird.[62]

Also in 2009, Madison ranked No. 2 on Newsmax magazine's list of the "Top 25 Most Uniquely American Cities and Towns," a piece written by CBS News travel editor Peter Greenberg.[63]

Every April, the Wisconsin Film Festival is held in Madison.[64] This five-day event features films from a variety of genres shown in theaters across the city. The University of Wisconsin–Madison Arts Institute sponsors the Film Festival.[65]

Music

Madison's vibrant music scene covers a wide spectrum of musical culture.[66]

Several venues offer live music nightly, spreading from the historic Barrymore Theatre and High Noon Saloon on the east side to[67] small coffee houses and wine bars. The biggest headliners usually perform at the Orpheum Theatre, the Overture Center, Breese Stevens Field, the Alliant Energy Center, or the UW Theatre on campus. Other popular rock and pop venues include the Majestic Theatre and the Frequency. During the summer, the Memorial Union Terrace on the University of Wisconsin campus, offers live music five nights a week. The Union is located on the shores of Lake Mendota and offers beautiful scenery and sunsets. Monona Terrace Community & Convention Center, located in the heart of downtown, also hosts free rooftop concerts during the summer months.

The Madison Scouts Drum and Bugle Corps has provided youth aged 16–22 opportunities to perform across North America every summer since 1938. The University of Wisconsin Marching Band is a popular marching band.

Popular bands and musicians

The band Garbage formed in Madison in 1994, and has sold 17 million albums.[68]

Madison has a lively independent rock scene, and local independent record labels include Crustacean Records, Science of Sound,[69] Kind Turkey Records,[70] and Art Paul Schlosser Inc. A Dr. Demento[71] and weekly live karaoke[72] favorite is The Gomers,[73] who have a Madison Mayoral Proclamation named after them.[74] They have performed with fellow Wisconsin residents Les Paul and Steve Miller.[75]

Madison is also home to other nationally known artists such as Paul Kowert of Punch Brothers, Mama Digdown's Brass Band, Clyde Stubblefield of Funky Drummer and James Brown fame, and musicians Roscoe Mitchell, Richard Davis, Ben Sidran, Sexy Ester and the Pretty Mama Sisters, Reptile Palace Orchestra, Ted Park, DJ Pain 1, Killdozer, Zola Jesus, Caustic, PHOX, Masked Intruder, and Lou & Peter Berryman, among others.

Music festivals

In the summer Madison hosts many music festivals, including the Waterfront Festival, the Willy St. Fair, Atwood Summerfest, the Isthmus Jazz Festival, the Orton Park Festival, 94.1 WJJO's Band Camp, Greekfest, the WORT Block Party and the Sugar Maple Traditional Music Festival, and the Madison World Music Festival sponsored by the Wisconsin Union Theater (held at the Memorial Union Terrace and at the Willy St. Fair in September). Past festivals include the Madison Pop Festival and Forward Music Festival (2009–2010.) One of the latest additions is the Fête de Marquette, taking place around Bastille Day at various east side locations. This new festival celebrates French music, with a focus on Cajun influences. Madison also hosts an annual electronic music festival, Reverence, and the Folk Ball, a world music and Folk dance festival held annually in January. Madison is home to the LBGTQA festival, Fruit Fest, celebrating queer culture and LGBT allies. Madison also plays host to the National Women's Music Festival.[76] UW-Madison also hosts the annual music and arts festival, Revelry, on campus at the Memorial Union each spring. The festival is put on by students for students as an end of the year celebration on campus.[77]

Art

Art museums include the UW–Madison's Chazen Museum of Art (formerly the Elvehjem Museum), and the Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, which annually organizes the popular Art Fair on the Square. Madison also has many independent art studios, galleries, and arts organizations, with events such as Art Fair Off the Square. Other museums include Wisconsin Historical Museum (run by the Wisconsin Historical Society),[78] the Wisconsin Veterans Museum,[79] the Madison Children's Museum.[80]

Performing arts

The Madison Opera, the Madison Symphony Orchestra, Forward Theater Company, the Wisconsin Chamber Orchestra, and the Madison Ballet are some of the professional resident companies of the Overture Center for the Arts. The city is also home to a number of smaller performing arts organizations, including a group of theater companies that present in the Bartell Theatre, a former movie palace renovated into live theater spaces, and Opera for the Young, an opera company that performs for elementary school students across the Midwest. The Wisconsin Union Theater (a 1,300-seat theater) is home to seasonal attractions and is the main stage for Four Seasons Theatre, a community theater company specializing in musical theater, and other groups. The Young Shakespeare Players, a theater group for young people, performs uncut Shakespeare and George B. Shaw plays.

Community-based theater groups include Children's Theatre of Madison, Strollers Theatre, Madison Theatre Guild, the Mercury Players, and Broom Street Theater (which is no longer on Broom Street).

Madison offers one comedy club, the Comedy Club on State (which hosts the Madison's Funniest Comic competition every year since 2010), owned by the Paras family. Madison has other options for more alternative humor, featuring several improv groups, such as Atlas Improv Co., Monkey Business Institute, as well as open-mics virtually every night.

Madison has one of the world's major entertainment industry archives at the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, part of the Wisconsin Historical Society.[81]

Architecture

The Wisconsin State Capitol dome was modeled after the dome of the U.S. Capitol, and was erected on the high point of the isthmus. Visible throughout the Madison area, a state law limits building heights within one mile (1.6 km) of the structure to 1,032.8 feet (314.8 m) above sea level to preserve the view of the building in most areas of the city.[82] Capitol Square is located in Madison's urban core, and is well-integrated with everyday pedestrian traffic and commerce. State Street and East Washington offer excellent views of the capitol.

Architect Frank Lloyd Wright spent much of his childhood in Madison and studied briefly at the university. Buildings in Madison designed by Wright include Usonian House, and the Unitarian Meeting House. Monona Terrace, now a convention and community center overlooking Lake Monona, was created by Anthony Puttnam—a student of Wright's—based on a 1957 Wright design. The Harold C. Bradley House in the University Heights neighborhood was designed collaboratively by Louis H. Sullivan and George Grant Elmslie in 1908–10, and now serves as the Sigma Phi Fraternity.

The Overture Center for the Arts opened 2004, and the adjacent Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, opened 2006, on State Street near the capitol were designed by architect César Pelli. Within the Overture Center are Overture Hall, Capitol Theater, and The Playhouse. Its modernist style, with simple expanses of glass framed by stone, was designed to complement nearby historic building facades.

The architectural firm Claude and Starck designed over 175 Madison buildings, and many are still standing, including Breese Stevens Field, Doty School (now condominiums), and many private residences.[83]

Architecture on the University of Wisconsin campus includes many buildings designed or supervised by the firm J. T. W. Jennings, such as the Dairy Barn and Agricultural Hall, or by architect Arthur Peabody, such as the Memorial Union and Carillon Tower. Several campus buildings erected in the 1960s followed the brutalist style. In 2005 the university embarked on a major redevelopment at the east end of its campus. The plan called for the razing of nearly a dozen 1950s to 1970s vintage buildings; the construction of new dormitories, administration, and classroom buildings; as well as the development of a new pedestrian mall extending to Lake Mendota. The campus now includes 12- to 14-story buildings.[84]

Points of interest

.jpg)

- Alliant Energy Center / Veteran's Memorial Coliseum and Exhibition Hall

- Camp Randall Stadium

- Chazen Museum of Art

- Madison Museum of Contemporary Art

- Madison Children's Museum

- Henry Vilas Zoo

- The Kohl Center

- Mifflin Street, home to the annual Mifflin Street Block Party

- Monona Terrace Community and Convention Center designed by Frank Lloyd Wright

- Memorial Union

- Olbrich Botanical Gardens

- Overture Center for the Arts

- Gates of Heaven, the eighth-oldest-surviving synagogue building in the U.S.

- State Street

- Williamson ("Willy") Street

- Smart Studios, Butch Vig and Steve Marker's longtime studio where many notable alternative rock records of the 1990s and 2000s were recorded and/or produced

- Unitarian Meeting House, another notable & tourable Frank Lloyd Wright structure, is adjacent to Madison city limits in suburban Shorewood Hills

- University of Wisconsin–Madison

- University of Wisconsin–Madison Arboretum

- University of Wisconsin Field House

- UW–Madison Geology Museum

- Wisconsin Historical Society/Wisconsin Historical Museum

- Wisconsin Veterans Museum

- Wisconsin State Capitol

- Lakeshore Nature Preserve, a campus-associated preserve which features notable long peninsula called Picnic Point

Nicknames

Over the years, Madison has acquired nicknames and slogans that include:

Sports

Madison's reputation as a sports city exists largely because of the University of Wisconsin. In 2004 Sports Illustrated on Campus named Madison the #1 college sports town in the nation.[93] Scott Van Pelt also proclaimed Madison the best college sports town in America.[94]

The UW–Madison teams play their home-field sporting events in venues in and around Madison. The football team plays at Camp Randall Stadium. In 2005 a renovation added 72 luxury suites and increased the stadium's capacity to 80,321, although crowds of as many as 83,000 have attended games. The basketball and hockey teams play at the Kohl Center. Construction on the $76 million arena was completed in 1997. In 2006, the men's and women's Badger hockey teams won NCAA Division I championships, and the women repeated with a second consecutive national championship in 2007.[95] Some events are played at the county-owned Alliant Energy Center (formerly Dane County Memorial Coliseum) and the University-owned Wisconsin Field House.

Despite Madison's strong support for college sports, it has proven to be an inhospitable home for professional baseball. The Madison Muskies, a Class A, Midwest League affiliate of the Oakland A's, left town in 1993 after 11 seasons. The Madison Hatters, another Class A, Midwest League team, played in Madison for only the 1994 season. The Madison Black Wolf, an independent Northern League franchise lasted five seasons (1996–2000), before decamping for Lincoln, Nebraska. Madison is home to the Madison Mallards, a college wood-bat summer baseball league team in the Northwoods League. They play in Warner Park on the city's north side from June to August.

The now defunct Indoor Football League's Madison Mad Dogs were once located in the city. In 2009 indoor football returned to Madison as the Continental Indoor Football League's Wisconsin Wolfpack, who call the Alliant Energy Center home.

Madison was once home to the semi-pro Madison Mustangs football team who played at Warner Park and Camp Randall Stadium in the 1960s and 1970s. Madison is once again home to a Madison Mustangs semi-pro football team that is part of the Ironman Football League. Games are typically played on Saturday during the summer months, with the home field being Middleton High School. The Mustangs have the nation's longest active winning streak at 49 games, and have won 4 straight Ironman Football League championships.

The Wisconsin Wolves is a women's semi-pro football team based in Madison that plays in the IWFL Independent Women's Football League. The Wolves home field is located at Middleton High School.

The Blackhawk Ski Club, formed in 1947, provides ski jumping, cross country skiing and alpine skiing. The club's programs have produced several Olympic ski jumpers, two Olympic ski jumping coaches and one Olympic ski jumping director. The club had the first Nordic ski facility with lighted night jumping.

The Madison 56ers is a Madison amateur soccer team in the National Premier Soccer League. They play in Breese Stevens Field on East Washington Avenue.[96]

Madison has several active ultimate disc leagues organized through the nonprofit Madison Ultimate Frisbee Association.[97] In 2013, the Madison Radicals, a professional ultimate frisbee team, debuted in the city.[98]

Madison is home to the Wisconsin Rugby Club, the 1998 and 2013 USA Rugby Division II National Champions, and the Wisconsin Women's Rugby Football Club, the state's only Division I women's rugby team. The city also has men's and women's rugby clubs at UW–Madison, in addition to four high school boys' teams and one high school girls' team. The most recent addition to the Madison rugby community, Madison Minotaurs Rugby Club, is composed largely of gay players and is Wisconsin's first and only IGRAB team, but is open to any player with any experience level. All ten teams play within the Wisconsin Rugby Football Union, the Midwest Rugby Union and USA Rugby.

Nearly 100 women participate in the adult women's ice hockey teams based in Madison (Thunder, Lightning, Freeze, UW–B and C teams), which play in the Women's Central Hockey League. The Madison Gay Hockey Association is also in Madison.

The Madison Curling Club was founded in 1921.[99] Team Spatola of the Madison Curling Club won the 2014 Women's US National Championship. Team members are: Nina Spatola, Becca Hamilton, Tara Peterson, Sophie Brorson.[100]

Madison's Gaelic sports club offers a hurling team organized as The Hurling Club of Madison, and a Gaelic football club, with men's and women's teams. These are amateur teams with open membership.

The roller derby league, Mad Rollin' Dolls, was formed in Madison in 2004 and is a member of the Women's Flat Track Derby Association.[101]

Madison is home to several endurance sports racing events, such as the Crazylegs Classic, Paddle and Portage, the Mad City Marathon, and Ironman Wisconsin, which attracts over 45,000 spectators.[102]

In 2014, the Madison Capitols began play in the United States Hockey League. The Capitols play their home games at Veterans Memorial Coliseum at the Alliant Energy Center. NHL player and Wisconsin Badgers alumnus Ryan Suter is a member of the team's ownership group.

As of 2017, the Reebok CrossFit Games will be held at the Alliant Energy Center. After seven years at the StubHub Center in Carson, California, the Games will move to a new location for at least the next three years. CrossFit chose the multi-building entertainment venue, which encompasses 164 acres, after posting a national request for proposals. The Dane County campus will be home to the Reebok CrossFit Games in 2017, 2018 and 2019.[103]

Current teams

| Club | League | Sport | Venue | Founded | Titles |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wisconsin Badgers | Big Ten, NCAA Div.1 | 23 Varsity Teams | Camp Randall Stadium, Kohl Center | 1849 | 27 |

| Madison College Wolfpack | N4C, NJCAA Div.3 | 8 varsity teams | Redsten Gymnasium, Roberts Field | 1912 | 21 |

| Wisconsin Rugby Club | WRFU | Rugby | Wisconsin Rugby Club Sports Complex | 1962 | 2 |

| Edgewood Eagles | NACC, NCAA Div.3 | 16 varsity teams | Edgedome | 1974 | 35 |

| Madison Mallards | NL | Baseball | Warner Park | 2001 | 2 |

| Madison 56ers | PLA | Soccer | Breese Stevens Field | 2005 | 0 |

| Madison Minotaurs | WRFU | Rugby | Yahara Rugby Field | 2007 | 0 |

| Madison Radicals | AUDL | Ultimate | Breese Stevens Field | 2013 | 1 |

| Madison Capitols | USHL | Hockey | Alliant Energy Center | 2014 | 0 |

| Mad Rollin' Dolls | WFTDA | Roller derby | Alliant Energy Center | 2004 | 0 |

| Mad-City Ski Team | NSSA | Show Skiing | Law Park | 1963 | 10 |

Government

Madison has a mayor-council system of government. Madison's city council, known as the Common Council, consists of 20 members, one from each district. The mayor is elected in a citywide vote.

Madison is the heart of Wisconsin's 2nd congressional district in the United States House of Representatives, represented by Mark Pocan (D). Mark F. Miller (D) and Fred Risser (D) represent Madison in the Wisconsin State Senate, and Robb Kahl (D), Melissa Sargent (D), Chris Taylor (D), Terese Berceau (D), and Lisa Subeck (D) represent Madison in the Wisconsin State Assembly.

Ron Johnson (R) and Tammy Baldwin (D) represent Madison, and all of Wisconsin, in the United States Senate. Baldwin is a Madison resident; she represented the 2nd from 1999 to 2013 before handing it to Pocan.

Emergency services

Madison Police Department

The Madison Police Department is the law enforcement agency in the city. It has been led by Chief Michael Koval since 2014.[104] The department has five districts: Central, East, North, South, and West, with a sixth "Midtown" District set to open in 2017.[105]

Special units

- K9 Unit

- Crime Scene Unit

- Forensic Unit

- Narcotics and Gangs Task Force

- Parking Enforcement

- Traffic Enforcement Safety Team

- S.W.A.T Team

- Special Events Team

- C.O.P.S (Safety Education)

- Mounted Patrol

- Crime Stoppers

- Amigos en Azul

Controversy

The Madison Police Department was criticized for absolving Officer Steve Heimsness of any wrongdoing in the November 2012 shooting death of an unarmed man, Paul Heenan. The department's actions resulted in community protests, including demands that the shooting be examined and reviewed by an independent investigative body.[106] WisconsinWatch.org called into question the MPD's facts and findings, stating that the use of deadly force by Heimsness was unwarranted.[107] There were calls for an examination of the Madison Police Department's rules of engagement and due process for officers who use lethal force in the line of duty.

Community criticism of the department's practices resurfaced after MPD officer Matt Kenny shot Tony Robinson, an unarmed man. The shooting was particularly controversial given the context of the ongoing Black Lives Matter movement. Due to new Wisconsin state legislation[108] that addresses the mechanisms under which officer-on-civilian violence is handled by state prosecutors, proceedings were handed over to a special unit of the Wisconsin Department of Justice in Madison. On March 27, 2015, the state concluded its investigation and gave its findings to Ismael Ozanne, the district attorney of Dane County.[109] On May 12, 2015, the shooting was determined to be justified self-defense by Ozanne.[110]

Madison Fire Department

The Madison Fire Department (MFD) provides fire protection and emergency medical services to the city. The MFD operates out of 13 fire stations,[111] with a fleet of 11 engines, 5 ladders,[112] 2 rescue squads, 2 hazmat units,[113] a lake rescue team,[114] and 8 ambulances.[115] The MFD also provides mutual aid to surrounding communities.[116][117][118]

Politics

City voters have supported the Democratic Party in national elections in the last half-century, and a liberal and progressive majority is generally elected to the city council. Detractors often refer to Madison as The People's Republic of Madison, the "Left Coast of Wisconsin" or as "77 square miles surrounded by reality." This latter phrase was coined by former Wisconsin Republican governor Lee S. Dreyfus, while campaigning in 1978, as recounted by campaign aide Bill Kraus.[6] In 2013, there was a motion in the city council to turn Dreyfus' insult into the official city "punchline," but it was voted down by the city council.[119]

The city's voters are generally much more liberal than voters in the rest of Wisconsin. For example, 76% of Madison voters voted against a 2006 state constitutional amendment to ban gay marriage,[120] even though the ban passed statewide with 59% of the vote.[121]

Current politics

Madison city politics remain dominated by activists of liberal and progressive ideologies. In 1992, a local third party, Progressive Dane, was founded. City policies supported in the Progressive Dane platform have included an inclusionary zoning ordinance, later abandoned by the mayor and a majority of the city council, and a city minimum wage. The party holds several seats on the Madison City Council and Dane County Board of Supervisors, and is aligned variously with the Democratic and Green parties.

In early 2011, Madison was the site for large protests against a bill proposed by Governor Scott Walker that abolished almost all collective bargaining for public worker unions.[122] The protests at the capitol ranged in size from 10,000 to over 100,000 people and lasted for several months.

Historical politics

In the 1960s and 1970s, the Madison counterculture was centered in the neighborhood of Mifflin and Bassett streets, referred to as "Miffland". The area contained many three-story apartments where students and counterculture youth lived, painted murals, and operated the co-operative grocery store, the Mifflin Street Co-op. Residents of the neighborhood often came into conflict with authorities, particularly during the administration of Republican mayor Bill Dyke. Dyke was viewed by students as a direct antagonist in efforts to protest the Vietnam War because of his efforts to suppress local protests. The annual Mifflin Street Block Party became a focal point for protest, although by the late 1970s it had become a mainstream community party.

During the late 1960s and early 1970s, thousands of students and other citizens took part in anti-Vietnam War marches and demonstrations, with more violent incidents drawing national attention to the city and UW campus. These include:

- the 1967 student protest of Dow Chemical Company, with 74 injured;

- the 1969 strike to secure greater representation and rights for African-American students and faculty, which resulted in the involvement of the Wisconsin Army National Guard;

- the 1970 fire that caused damage to the Army ROTC headquarters housed in the Old Red Gym, also known as the Armory; and

- the 1970 late-summer predawn ANFO bombing of the Army Mathematics Research Center in Sterling Hall, killing a postdoctoral researcher, Robert Fassnacht. (See Sterling Hall bombing)

These protests were the subject of the documentary The War at Home.[123] David Maraniss's book, They Marched into Sunlight, incorporated the 1967 Dow protests into a larger Vietnam War narrative. Tom Bates wrote the book Rads on the subject ( ISBN 0-06-092428-4). Bates wrote that Dyke's attempt to suppress the annual Mifflin Street block party "would take three days, require hundreds of officers on overtime pay, and engulf the student community from the nearby Southeast Dorms to Langdon Street's fraternity row. Tear gas hung like heavy fog across the Isthmus." In the fracas, student activist Paul Soglin, then a city alderman, was arrested twice and taken to jail. Soglin was later elected mayor of Madison, serving from 1973 to 1979, 1989 to 1997, and is the current mayor, elected again in April 2011. During his middle term he led the construction of the Frank Lloyd Wright designed Monona Terrace.

Political groups and publications

Madison is home to the Freedom from Religion Foundation, a non-profit organization that promotes the separation of church and state. The largest national organization advocating for non-theists, FFRF is known for its lawsuits against religious displays on public property and for advocating removal of "In God We Trust" from American currency. The group publishes a monthly newspaper, Freethought Today.

Madison is associated with "Fighting Bob" La Follette and the Progressive movement. La Follette's magazine, The Progressive, founded in 1909, is still published in Madison.

Crime

| Year | Homicides | Robbery | Burglary |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1976[124] | 6 | 114 | 2292 |

| 1977[125] | 4 | 122 | 2440 |

| 1986[124] | 3 | 211 | 1988 |

| 1996[124] | 1 | 301 | 1389 |

| 1999[124] | 6 | 265 | 1356 |

| 2000[125] | 4 | 286 | 1267 |

| 2001[125] | 6 | 295 | 1358 |

| 2002[125] | 5 | 269 | 1570 |

| 2003[125] | 6 | 282 | 1611 |

| 2004[125] | 3 | 292 | 1467 |

| 2005[125] | 3 | 330 | 1462 |

| 2006[125] | 4 | 435 | 1627 |

| 2007[125] | 8 | 410 | 2059 |

| 2008[125] | 10 | 368 | 2038 |

| 2009[125] | 4 | 364 | 1523 |

| 2010[126] | 2 | 333 | 1652 |

| 2011[126] | 7 | 272 | 1446 |

| 2012[127] | 3 | 249 | 1594 |

| 2013[127] | 5 | 301 | 1360 |

| 2014[128] | 5 | 225 | 1126 |

| 2015[128] | 6 | 222 | 1208 |

In 2008, Men's Health magazine ranked Madison as the "Least Armed and Dangerous" city in the United States in an article about "Where Men Are Targets".[129] There were 53 homicides reported by Madison Police from 2000 to 2009.[125] The highest total was 10 in 2008.[130] Police reported 28 murders from 2010 to 2015, with the highest year being 7 murders in 2011.[126][127][128]

Education

According to Forbes magazine, Madison ranks second in the nation in education.[131][132] The Madison Metropolitan School District serves the city and surrounding area. With an enrollment of approximately 25,000 students in 46 schools, it is the second largest school district in Wisconsin behind the Milwaukee School District.[133] The five public high schools are James Madison Memorial, Madison West, Madison East, La Follette, and Malcolm Shabazz City High School, an alternative school.

Among private church-related high schools are Abundant Life Christian School, Edgewood High School,[134] near the Edgewood College campus, and St. Ambrose Academy, a Catholic school offering grades 6 through 12.[135] Madison Country Day School is a private high school with no religious affiliation.

The city is home to the University of Wisconsin–Madison, Edgewood College, Madison Area Technical College, and Madison Media Institute, giving the city a post-secondary student population of nearly 55,000. The University of Wisconsin accounts for the vast majority of students, with an enrollment of roughly 44,000, of whom 31,750 are undergraduates.[136] In a Forbes magazine city ranking from 2003, Madison had the highest number of Ph.D.s per capita, and third-highest college graduates per capita, among cities in the United States.[137]

Additional degree programs are available through satellite campuses of Cardinal Stritch University, Concordia University-Wisconsin, Globe University, Lakeland College, the University of Phoenix, and Upper Iowa University. Madison also has a non-credit learning community with multiple programs and many private businesses also offering classes.

Media

Madison is home to an extensive and varied number of print publications, reflecting the city's role as the state capital and its diverse political, cultural and academic population. The Wisconsin State Journal (weekday circulation: ~95,000; Sundays: ~155,000) is published in the mornings, while its sister publication, The Capital Times (Thursday supplement to the Journal) is published online daily, with two printed editions a week. Though jointly operated under the name Capital Newspapers, the Journal is owned by the national chain Lee Enterprises, and the Times is independently owned. Wisconsin State Journal is the descendant of the Wisconsin Express, a paper founded in the Wisconsin Territory in 1839. The Capital Times was founded in 1917 by William T. Evjue, a business manager for the State Journal who disagreed with that paper's editorial criticisms of Wisconsin Republican Senator Robert M. La Follette, Sr. for his opposition to U.S. entry into World War I.

The free weekly alternative newspaper Isthmus (weekly circulation: ~65,000) was founded in Madison in 1976. The Onion, a satirical weekly, was founded in Madison in 1988 and published from there until it moved to New York in 2001. Two student newspapers are published during the academic year, The Daily Cardinal (Mon-Fri circulation: ~10,000) and The Badger Herald (Mon-Fri circulation: ~16,000). Other specialty print publications focus on local music, politics and sports, including The Capital City Hues,[138][139][140] The Madison Times,[139][140] Madison Magazine, The Simpson Street Free Press, Umoja Magazine,[139][140][141][142] and fantasy-sports web site RotoWire.com. Local community blogs include Althouse and dane101.

The Progressive, published in Madison, is a left-wing periodical that may be best known for the attempt of the U.S. government in 1979 to suppress one of its articles before publication. The magazine eventually prevailed in the landmark First Amendment case, United States v. The Progressive, Inc. During the 1970s, there were two radical weeklies published in Madison, known as TakeOver and Free for All, as well as a Madison edition of the Bugle-American underground newspaper.

Radio

Madison has three large media companies that own the majority of the commercial radio stations within the market. These companies consist of iHeartMedia, Entercom Communications, and Mid-West Family Broadcasting as well as other smaller broadcasters. Madison is home to Mid-West Family Broadcasting, which is an independently-owned broadcasting company that originated and is headquartered in Madison. Mid-West Family owns radio stations throughout the state and the Midwest.

Madison hosts two volunteer-operated and community-oriented radio stations, WORT and WSUM. WORT Community Radio (89.9 FM), founded in 1975, is one of the oldest volunteer-powered radio stations in the United States. A listener-sponsored community radio station, WORT offers locally produced diverse music and talk programming. WSUM (91.7 FM) is a free-form student radio station programmed and operated almost entirely by students.

Madison's Wisconsin Public Radio station, WHA, was one of the first radio stations in the nation to begin broadcasting,[143] and remains the longest continuously broadcasting station in the nation. Widely heard public radio programs that originate at the WPR studios include Michael Feldman's Whad'Ya Know?, Zorba Pastor On Your Health, To the Best of Our Knowledge and Calling All Pets.

WXJ-87 is the NOAA Weather Radio All Hazards station on Madison's west side, with broadcasts originating from the National Weather Service in Sullivan, Wisconsin.

TV

Madison has five commercial and two public television stations. The commercial stations consist of WISC-TV "News 3" (CBS), WMTV-TV "NBC 15" (NBC), WKOW-TV "27 News" (ABC), WMSN-TV "FOX 47" (Fox), and WIFS "Wisconsin's 57" (independent). Madison has two public television stations: WHA-TV, which is owned by the University of Wisconsin–Extension, airs throughout the state, with the exception of Milwaukee, and Madison City Channel, which is owned and operated by the City of Madison covering city governmental affairs.

Infrastructure

Transportation

Madison is served by the Dane County Regional Airport, which serves nearly 1.6 million passengers annually. Most major general aviation operations take place at Morey Field in Middleton 15 miles (24 km) from Madison's city center. Madison Metro operates bus routes throughout the city and to some neighboring suburbs.[144] Madison has four taxicab companies (Union, Badger, Madison, and Green), and several companies provide specialized transit for individuals with disabilities. Several carsharing services are also available in Madison, including Community Car, a locally owned company, and U-Haul subsidiary Uhaul Car Share.

Starting from the last decades of the 20th century, Madison has been among the leading cities for bicycling as a form of transportation, with about 3% of working residents pedaling on their journey to work.[145] The share of Madison workers who bicycled to work increased to 5.3% by 2014.[146] According to the 2016 American Community Survey, 65.7% of working Madison residents commuted by driving alone, 6.7% carpooled, 8.6% used public transportation, and 8.5% walked. About 6% used all other forms of transportation, including bicycles, motorcycles, and taxis. About 4.5% worked at home.[147]

In 2015, 11.2% of Madison households were without a car, which was unchanged in 2016. The national average was 8.7% in 2016. Madison averaged 1.5 cars per household in 2016, compared to a national average of 1.8 per household.[148]

Bicycling

Madison is known for its extensive biking infrastructure, with numerous bike paths and bike lanes throughout the city. Several of these bike paths connect to state trails, such as the Capital City State Trail, Military Ridge State Trail, and Badger State Trail. In addition to these bike paths, most city streets have designated bike lanes or are designated as bicycle boulevards, which give high priority to bicyclists. In 2015 Madison was awarded platinum level Bicycle Friendly Community designation from the League of American Bicyclists, one of only five cities in the US to receive this (highest) level.[149]

Railways

Passenger train service between Madison and Chicago, on the Sioux and the Varsity, provided by the Milwaukee Road, ended in 1971 with Amtrak absorbing passenger train services. Prior to 1960, the Sioux train offered service west to Rapid City, South Dakota. Until the 1950s the Chicago and North Western Railway operated passenger trains through the city. A high-speed rail route from Chicago through Milwaukee and Madison to Minneapolis–Saint Paul, Minnesota, was proposed as part of the Midwest Regional Rail Initiative. Funding for the railway connecting Madison to Milwaukee was approved in January 2010, but Governor-elect Scott Walker's opposition to the project led the Federal Railroad Administration to retract the $810 million in funding and reallocate it to other projects.[150] The nearest passenger train station is in Columbus, Wisconsin, 28 miles (45 km) away to the northeast. There, the eastbound Empire Builder provides daily service to Milwaukee and Chicago, and the westbound Empire Builder provides daily service to Portland, Oregon and Seattle, Washington.

Railroad freight services are provided to Madison by Wisconsin and Southern Railroad (WSOR) and Canadian Pacific Railway (CP). Wisconsin & Southern has been operating since 1980, having taken over trackage owned since the 19th century by the Chicago and North Western and the Milwaukee Road.

Buses

In addition to public transportation, regional buses connect Madison to Milwaukee, Chicago, Minneapolis–Saint Paul, and many other communities. Badger Bus,[151] which connects Madison and Milwaukee, runs several trips daily. Greyhound Lines, a nationwide bus company, serves Madison on its Chicago, Milwaukee, and Minneapolis–Saint Paul route. Van Galder Bus Company, a subsidiary of Coach USA, provides transportation through Rockford to Chicago—stopping at Union Station, O'Hare Airport, and Midway Airport. Jefferson Lines provides transportation to Minneapolis–Saint Paul via La Crosse. Megabus provides limited-stop service to Chicago and Minneapolis–Saint Paul. Lamers Bus Lines has once daily trips from Madison to Wausau, Dubuque, and Green Bay.

Highways

Interstates I-39 and I-90 run along the east side of the city, connecting the city to Chicago, Janesville, Rockford, La Crosse and Wausau. I-39 and I-90 intersect with Interstate 94 in Madison, connecting the city to Milwaukee and Minneapolis–Saint Paul. Interstates 90 and 39 are currently being expanded to six lanes from the state line to Madison and eight lanes in Janesville.

U.S. Route 151 runs through downtown and serves as the main thoroughfare through the northeast and south-central parts of the city, connecting Madison with Dubuque, Iowa, as well as the Wisconsin cities of Fond du Lac and Manitowoc. The West Beltline Highway, frequently referred to by locals as the Beltline, is a six-to-eight-lane freeway serving the south and west sides of Madison and is the main link from downtown to the southeast and western suburbs. U.S. Routes US-14, US-18, and US-51 also run through the city.

Utilities

In the mid-2000s Madison partnered with Merrimac Communications to develop and build Mad City Broadband, a wireless internet infrastructure for the city.[152] In early 2010 a grass-root effort to bring Google's new high-speed fiber Internet to Madison failed.[153]

Madison is served by Madison Gas and Electric and Alliant Energy, which provide electricity and natural gas service to the city.

Notable Madisonians

Sister cities

Former sister cities include:

See also

Notes

- ↑ Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the expected highest and lowest temperature readings at any point during the year or given month) calculated based on data at said location from 1981 to 2010.

- ↑ Official weather records for Madison were kept at downtown from January 1869 to December 1946 and at KMSN since January 1947. For more information, see ThreadEx.

References

- 1 2 "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 14, 2012. Retrieved 2012-11-18.

- 1 2 "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2012-11-18.

- 1 2 "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved June 7, 2018.

- ↑ "Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2018-06-21.

- ↑ Mollenhoff, David V. (2003) Madison, a History of the Formative Years. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, p. 26. ISBN 0-299-19980-0

- 1 2 Moe, Doug (2005). Surrounded by Reality. Madison: Jones Books. p. xiii. ISBN 0-9763539-3-8.

- ↑ Gilbert, Craig. "Wisconsin's status as a presidential battleground in question". jsonline.com. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ↑ Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ↑ Mollenhoff, David V. (2003) Madison, a History of the Formative Years Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 0-299-19980-0. Page 26.

- ↑ Historic Madison, Inc., Madison's Past – Early History

- ↑ Supreme Court, History: The Supreme Court Hearing Room Wisconsin Court System.

- ↑ "Vilas vs. Reynolds". Reports of cases argued and determined in the Supreme Court of the State of Wisconsin. 6. Beloit: E.E. Hale & Co. 1858. p. 215. Retrieved 2011-07-24.

- ↑ Madison, Dane County and Surrounding Towns, Madison: Wm. J. Park, 1877, pp. 543–558.

- ↑ "Wisconsin State Capitol Tour". State of Wisconsin. Archived from the original on May 27, 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-24.

- ↑ "2003 City of Madison, City of Fitchburg and Town of Madison Cooperative Plan" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-11-14.

- ↑ "Dictionary of Wisconsin History: Four Lakes". Wisconsin Historical Society.

- ↑ "City of Madison Website, Communities and Neighborhoods".

- ↑ Times, Steven Elbow | The Capital. "Madison's Williamson-Marquette neighborhood named one of nation's top 10". madison.com. Retrieved 2018-07-17.

- 1 2 "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2018-03-09.

- ↑ "Station Name: WI MADISON DANE RGNL AP". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2018-03-09.

- ↑ "WMO Climate Normals for MADISON/DANE CO REGIONAL ARPT, WI 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2014-03-10.

- ↑ "Monthly Averages for Madison, WI – Temperature and Precipitation". The Weather Channel. Archived from the original on January 11, 2012. Retrieved May 25, 2010.

- ↑ United States Census Bureau. "Census of Population and Housing". Archived from the original on May 12, 2015. Retrieved August 22, 2014.

- ↑ U.S. Office of Management and Budget, Metropolitan Statistical Areas and Components Archived May 26, 2007, at the Wayback Machine., 2007-05-11. Accessed 2008-08-01.

- ↑ U.S. Office of Management and Budget, Micropolitan Statistical Areas and Components Archived June 29, 2007, at the Wayback Machine., 2007-05-11. Accessed 2008-08-01.

- ↑ U.S. Office of Management and Budget, Combined Statistical Areas and Component Core Based Statistical Areas Archived June 29, 2007, at the Wayback Machine., 2007-05-11. Accessed 2008-08-01.

- ↑ United States Census Bureau. Annual Estimates of the Resident Population: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2016 - United States -- Metropolitan Statistical Area; and for Puerto Rico: 2016 Population Estimates.

- ↑ United States Census Bureau. Annual Estimates of the Resident Population: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2016 - United States -- Combined Statistical Area; and for Puerto Rico: 2016 Population Estimates.

- ↑ "Roman Catholic Diocese of Madison home page". Madisondiocese.org. Archived from the original on November 22, 2011. Retrieved November 14, 2011.

- ↑ "New life for St. Raphael Cathedral site". madison.com.

- ↑ Walton, Christopher. "What size are Unitarian Universalist congregations?". uuworld.org. Retrieved January 6, 2013.

- ↑ "Tours". First Unitarian Meeting Society.

- ↑ city-data.com

- ↑ "Best Places for Business Forbes, May 22, 2006.

- ↑ Brennan, Morgan. "Madison, Wis. - pg.14". Forbes. Retrieved 2018-02-28.

- ↑ Altman, Ian. "No. 17 Madison, Wisconsin - pg.17". Forbes. Retrieved 2018-02-28.

- ↑ Carlyle, Erin. "Madison, Wisc. - pg.6". Forbes. Retrieved 2018-02-28.

- ↑ Avenue, Next. "No. 1: Madison, Wisc. - pg.2". Forbes. Retrieved 2018-02-28.

- ↑ Weiss, Tara (January 5, 2009). "No. 1: Madison, Wis". 10 Cities Where They're Hiring. Forbes. Retrieved 2011-07-24.

- ↑ Steven R. Williams, Webmaster. "Wisconsin State Employees Union website". Wseu-24.org. Archived from the original on 1998-12-01. Retrieved 2011-11-14.

- ↑ "Best Hospitals 2006: University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinics, Madison". U. S. News and World Reports. 2006. Archived from the original on January 14, 2006. Retrieved September 12, 2006.

- ↑ "St. Mary's Hospital". Stmarysmadison.com. Retrieved 2011-11-14.

- ↑ Plas, Joe Vanden. Google joins Microsoft in opening Madison office, WTN News, April 2008

- ↑ Newman, Judy (April 22, 2006). "At Covance, People Volunteer for Cash, Causes". The Wisconsin State Journal. Retrieved February 10, 2011.

- ↑ Guy Boulton. "As Epic Systems has soared, Madison has become a center for health information technology". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, October 6, 2017.

- ↑ "Our Story, Rocky's Roots". Rockyrococo.com. Archived from the original on November 15, 2011. Retrieved 2011-11-14.

- ↑ "About Us | About Us". Glassnickelpizza.com. November 5, 1997. Archived from the original on November 23, 2011. Retrieved November 14, 2011.

- ↑ "Madison, Wis., No. 1 Place to Live in U.S., Money Magazine Says.(Originated from The Wisconsin State Journal)". Knight Ridder/Tribune Business News. June 13, 1996.

- ↑ "About the Market". Dane County Farmers' Market. Archived from the original on December 12, 2016. Retrieved December 8, 2016.

- ↑ "Wisconsin Chamber Orchestra". Wcoconcerts.com. Retrieved 2011-11-14.

- ↑ "Madison Home Brewers and Tasters Guild". Mhtg.org. November 5, 2011. Retrieved 2011-11-14.

- ↑ Rhythm and Booms press release Archived September 17, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ 3000, Channel. "New fireworks show to replace Rhythm and Booms". Retrieved 2015-09-23.

- ↑ Severson, Gordon. "Rhythm & Booms replaced with Shake the Lake in downtown Madison". Retrieved 2015-09-23.

- ↑ "Hoofer Sailing – Snow Kiting". Hoofersailing.org. Archived from the original on August 18, 2011. Retrieved November 14, 2011.

- ↑ "Best College Sports Towns: Madison #1" from Sports Illustrated

- ↑ "Madison boasts popular bike trails - The Daily Cardinal". The Daily Cardinal. Retrieved 2018-02-28.

- ↑ Greater Madison Convention and Visitors Bureau."Madison Ranked Among Nation's Best Gay-Friendly Places to Call Home" Archived March 7, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.. December 12, 2005.

- ↑ "Gay Demographics 2000 Census". Gaydemographics.org. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved November 14, 2011.

- ↑ "Madison WI news sports entertainment". Madison.com. Archived from the original on October 7, 2008. Retrieved November 14, 2011.

- ↑ "University of Wisconsin-Madison". The Daily Cardinal. Retrieved 2011-11-14.

- ↑ "Council Makes Plastic Flamingo Madison's Official Bird". WISC-TV. September 2, 2009. Archived from the original on September 3, 2009. Retrieved 2009-09-02.

- ↑ Greenberg, Peter. "Newsmax Magazine Rates the Top 25 Most Uniquely American Cities And Towns". Newsmax. Retrieved January 13, 2014.

- ↑ "Wisconsin Film Festival | Madison". www.wifilmfest.org. Retrieved 2015-10-28.

- ↑ "Home | Arts Institute". artsinstitute.wisc.edu. Retrieved 2015-10-28.

- ↑ "Madison Music Events, Shows & Things To Do". Zvents. Archived from the original on 2011-02-25. Retrieved 2011-11-14.

- ↑ "Live Music Venue Madison WI – High Noon Saloon". High-noon.com. Retrieved 2011-11-14.

- ↑ "Garbage". Last.fm. Retrieved 2016-12-08.

- ↑ "Science of Sound – Independent Record Label – Madison Wisconsin". scienceofsound.com. Archived from the original on January 27, 2016. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

- ↑ "Kind Turkey Records". Kind Turkey Records. Retrieved 2011-11-14.

- ↑ "The Gomers". Themadmusicarchive.com. December 1, 1986. Archived from the original on February 4, 2010. Retrieved 2011-11-14.

- ↑ "High Noon Saloon". High-noon.com. Retrieved 2011-11-14.

- ↑ SCENE: CD Reviews Archived November 23, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Gomers e-Presskit". Beeftone.com. Archived from the original on 2005-12-28. Retrieved 2011-11-14.

- ↑ Wisconsin Foundation for School Music : 2004 Lifetime Achievement Award Archived September 30, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ , website.

- ↑ "revelryfest". revelryfest. Archived from the original on March 26, 2015.

- ↑ "Wisconsin Historical Museum". Wisconsinhistory.org. Retrieved 2011-11-14.

- ↑ "Wisconsin Veterans Museum". Museum.dva.state.wi.us. Retrieved 2011-11-14.

- ↑ "Madison Children's Museum". Madisonchildrensmuseum.com. Retrieved 2011-11-14.

- ↑ Directors Guild of America, Visual History Resources. Retrieved December 3, 2012.

- ↑ "1989 Wisconsin Act 222" (PDF). State of Wisconsin. April 12, 1990. Retrieved 2006-10-03.

- ↑ "Behold ... The Genius Of Claude And Starck Archived September 29, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "By any measure, Madison is getting taller". madison.com.

- ↑ Clark, Brian E. (October 19, 2008). "Mad City offers more than football". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on November 25, 2008. Retrieved January 25, 2010.

- ↑ "COLLEGE BASKETBALL '93–'94; Mad, Mad, Mad City: Wisconsin Is Reborn". The New York Times. December 5, 1993. Retrieved 2010-05-12.

- ↑ "The Milwaukee Sentinel – Google News Archive Search". google.com.

- ↑ "Milwaukee Journal Sentinel – Google News Archive Search". google.com.

- ↑ "Madison named one of the most gay-friendly cities in America – WKOW 27: Madison, WI Breaking News, Weather and Sports". Wkowtv.com. January 14, 2010. Retrieved 2011-11-14.

- ↑ Mosiman, Dean (July 12, 2013). "Mayor proposes city motto: '77 Square Miles Surrounded by Reality'". Wisconsin State Journal. Retrieved February 22, 2017.

- ↑ "The Milwaukee Journal – Google News Archive Search". google.com.

- ↑ "Polarisation in the People's Republic of Madison". The Economist, June 5, 2012. Accessed November 5, 2016.

- ↑ "Best College Sports Towns". CNN. Retrieved 2010-05-12.

- ↑ Archived September 30, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ University of Wisconsin Badger Hockey Archived November 12, 2006, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Princeton-56ers Archived October 23, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "About MUFA". The Madison Ultimate Frisbee Association. Archived from the original on October 26, 2016.

- ↑ Rob Thomas. "Radical, dude: Pro ultimate Frisbee team debuts in Madison". madison.com.

- ↑ "Madison Curling Club". madisoncurlingclub.com.

- ↑ "Page not found – Madison Curling Club". Archived from the original on July 27, 2014. Retrieved December 8, 2016.

- ↑ "Mad Rollin' Dolls". Madrollindolls.com. Retrieved 2011-11-14.

- ↑ "IRONMAN Wisconsin". Retrieved December 8, 2016.

- ↑ "Games Move to Madison". Retrieved December 8, 2016.

- ↑ "Chief Koval's Bio – Chief's Office – Madison Police Department – City of Madison, Wisconsin". Retrieved December 8, 2016.

- ↑ "Blog – Chief's Office – Madison Police Department – City of Madison, Wisconsin". Retrieved December 8, 2016.

- ↑ "Madison rally calls for independent review of fatal police shooting". madison.com.

- ↑ WisconsinWatch.org. "Police account of shooting disputed"

- ↑ "2013 Assembly Bill 409". wisconsin.gov.

- ↑ Nico Savidge – Wisconsin State Journal. "Tony Robinson shooting investigation will be turned over to district attorney on Friday". madison.com.

- ↑ Berman, Mark (May 12, 2015). "Madison police officer won't be charged for shooting Tony Robinson". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 12, 2015.

- ↑ "Fire Suppression". cityofmadison.com. Madison, Wisconsin: Fire Department. Retrieved December 18, 2016.

Madison has thirteen (13) fire stations serving the city.

- ↑ "What we do". cityofmadison.com. Madison, Wisconsin: Fire Department. Retrieved December 18, 2016.

- ↑ "Hazardous Incident Team". cityofmadison.com. Madison, Wisconsin: Fire Department. Retrieved December 18, 2016.

- ↑ "Lake Rescue Team". cityofmadison.com. Madison, Wisconsin: Fire Department. Retrieved December 18, 2016.

- ↑ "EMS". cityofmadison.com. Madison, Wisconsin: Fire Department.

Each day, eight medics (or ambulances) are in service, each staffed by two paramedics.

- ↑ "Organization". cityofmadison.com. Madison, Wisconsin: Fire Department. Archived from the original on December 22, 2016. Retrieved December 18, 2016.

- ↑ "Annual Reports". cityofmadison.com. Madison, Wisconsin: Fire Department. Retrieved December 18, 2016.

- ↑ "History". cityofmadison.com. Madison, Wisconsin: Fire Department. Retrieved December 18, 2016.

- ↑ "Madison to stay real: City Council rejects Soglin's proposed slogan". ibmadison.com.

- ↑ "Fair Wisconsin News Release". Retrieved 2007-04-14.

- ↑ "Key Ballot Measures". CNN.com. Retrieved 2007-04-16.

- ↑ "Angry Demonstrations in Wisconsin as Cuts Loom". The New York Times. February 17, 2011. Retrieved December 8, 2016.

- ↑ "The War at Home (1979) Review Summary". New York Times. Retrieved July 10, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 "Annual Report" (PDF). Madison Police. 2006. Retrieved December 18, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "Annual Report" (PDF). Madison Police. 2009. Retrieved December 18, 2016.

Page 17 lists violent crime totals for 2000 to 2009

- 1 2 3 "Annual Report" (PDF). Madison Police. 2011. Retrieved December 18, 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Annual Report" (PDF). Madison Police. 2013. Retrieved December 18, 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Annual Report" (PDF). Madison Police. 2015. Retrieved December 18, 2016.

- ↑ Watkins, Denny. "Where Men Are Targets". Men's Health. No. June 2008. p. 102. Retrieved December 18, 2016.

- ↑ "Homicides 2008" (PDF). City of Madison. January 31, 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 31, 2010.

- ↑ "Where To Educate Your Children" Forbes, December 12, 2007.

- ↑ "In Pictures: Top 20 Places To Educate Your Child" Forbes, December 12, 2007.

- ↑ "Madison Metropolitan School District". Madison.k12.wi.us. Retrieved 2011-11-14.

- ↑ "Edgewood High School". Edgewood.k12.wi.us. Archived from the original on October 21, 2011. Retrieved 2011-11-14.

- ↑ Faith Haven Archived September 29, 2008, at the Wayback Machine., Madison, Wis. Capital Times, October 13, 2006.

- ↑ "#415 University of Wisconsin, Madison". Forbes. August 5, 2009.

- ↑ "Forbes rating is more than kudos for Madison; it's a reflection on Wisconsin and the Midwest". Wisconsin Education Association Council. May 17, 2004. Archived from the original on June 3, 2004.

- ↑ The Capital City Hues

- 1 2 3 Madison Public Library. News and Media

- 1 2 3 Jordan S. Gaines. "Madison 365 news site will give voice to communities of color". The Capital Times, July 20, 2015.

- ↑ "Umoja Magazine". Retrieved December 8, 2016.

- ↑ Robyn Norton. "On View | A Mirror Image: The Village Reflects on Itself". Wisconsin State Journal, June 14, 2015. "UMOJA Magazine celebrates 25 years"

- ↑ "PortalWisconsin.org". portalwisconsin.org.

- ↑ "Metro Transit System". Ci.madison.wi.us. Retrieved 2011-11-14.

- ↑ Douma, Frank and Fay Cleaveland (2008). "The Impact of Bicycling Facilities on Commute Mode Share" (PDF). Minnesota Department of Transportation. Retrieved May 7, 2018.

- ↑ "WHERE WE RIDE: Analysis of bicyclecommuting in American cities" (PDF). The League of american Bicyclists. Retrieved May 7, 2018.

- ↑ "Means of Transportation to Work by Age". Census Reporter. Retrieved May 7, 2018.

- ↑ "Car Ownership in U.S. Cities Data and Map". Governing. Retrieved May 7, 2018.

- ↑ Journal, David Wahlberg | Wisconsin State. "Madison one of 5 platinum-level Bicycle Friendly Communities". Retrieved December 8, 2016.

- ↑ "Statement From The U.S. Department Of Transportation". Dot.gov. December 9, 2010. Archived from the original on December 11, 2010. Retrieved 2011-11-14.

- ↑ "Badger Bus Schedule". wanderu.com.

- ↑ Mad City Broadband "Mad City Broadband"

- ↑ Google Fiber draws Madisonian support "Google Fiber draws Madisonian support"

Further reading

- Bates, Tom, Rads: The 1970 Bombing of the Army Math Research Center at the University of Wisconsin–Madison and Its Aftermath (1993) ISBN 0-06-092428-4

- Durrie, Daniel S. A History of Madison, the Capital of Wisconsin; Including the Four Lake Country. Madison: Atwood & Culver, 1874.

- Madison, Dane County and Surrounding Towns. Madison: Wm. J. Park & Co., 1877.

- Maraniss, David, They Marched Into Sunlight: War and Peace Vietnam and America October 1967 (2003) ISBN 0-7432-1780-2 ISBN 0-7432-6104-6 (about the Dow Chemical protest, and a battle in Vietnam that took place the previous day)

- Nolen, John. Madison: a Model City. Boston: 1911.

- Thwaites, Reuben Gold. The Story of Madison. J. N. Purcell, 1900.

External links

- Official website