Pago Pago

| Pago Pago | |

|---|---|

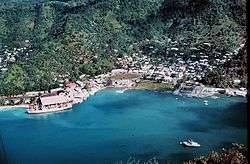

A portion of the docks at Fagatogo in Pago Pago Harbor. In the background is the tallest peak on Tutuila, Matafao. | |

Pago Pago | |

| Coordinates: 14°16′46″S 170°42′02″W / 14.27944°S 170.70056°W | |

| Country |

|

| Territory |

|

| Elevation | 9 m (30 ft) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 3,656 |

| Time zone | UTC−11 (Samoa Time Zone) |

| ZIP code | 96799[1] |

| Area code(s) | +1 684 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1389119[2] |

| Website | www.pagopago.com |

Pago Pago (/ˈpɑːŋɡoʊˈpɑːŋɡoʊ/; Samoan: [ˈpaŋo ˈpaŋo]; pronounced pahng-oh pahng-oh)[3] is the territorial capital of American Samoa. It is in Maoputasi County on the main island of American Samoa, Tutuila. It is home to one of the best and deepest natural deepwater harbors in the South Pacific Ocean, sheltered from wind and rough seas, and strategically located.[4][5][6] The harbor is also one of the best protected in the South Pacific,[7] which gives American Samoa a natural advantage with respect to landing fish for processing.[8] Tourism, entertainment, food, and tuna canning are its main industries. Pago Pago was the world's 4th largest tuna processor as of 1993.[9] It was home to two of the largest tuna companies in the world: Chicken of the Sea and StarKist, which exported an estimated $445 million in canned tuna to the U.S. mainland.[10]

Pago Pago is the only modern urban center in American Samoa.[11] The Greater Pago Pago Metropolitan Area encompasses several villages strung together along Pago Pago Harbor.[12] One of the villages is itself named Pago Pago, and in 2010 had a population of 3,656. The constituent villages are, in order, Utulei, Fagatogo, Malaloa, Pago Pago, Satala and Atu'u. Fagatogo is the downtown area referred to as Town and is home to the legislature, while the executive is located in Utulei. In Fagatogo is the Fono, Police Department, Port of Pago Pago, many shops and hotels. The Greater Pago Pago Area was home to 8,000 residents in 2000.[13]

Rainmaker Mountain (Mount Pioa) is located in Pago Pago, and gives the city the highest annual rainfall of any harbor in the world.[14][15]

Etymology

The letter “g” in Samoan sounds like “ng”, which is why Pago Pago is pronounced “Pango Pango.”[16][17]

History

_(14780577521).jpg)

Pago Pago was first settled 4,000 years ago.[18]

19th century

As early as 1839, American interest was generated for the Pago Pago area when Commander Charles Wilkes, head of the United States Exploring Expedition, surveyed the Pago Pago Harbor and the island. Rumors of possible annexation by Britain or Germany were taken seriously by the U.S., and the U.S. Secretary of State Hamilton Fish sent Colonel Albert Steinberger to negotiate with Samoan chiefs on behalf of American interests.[19]

The chief of Pago Pago signed a treaty with the U.S. in 1872, giving the American government considerable influence on the island.[20] It was acquired by the United States through a treaty in 1877.[21] One year after the naval base was built at Pearl Harbor in 1887, the U.S. government established a naval station in Pago Pago.[22] It was primarily used as a fueling station for both naval- and commercial ships.[23]

The U.S. Navy first established a coaling station in 1878, right outside Fagatogo. The United States Navy later bought land east of Fagatogo and on Goat Island, an adjacent peninsula. Sufficient land was obtained in 1898 and the construction of United States Naval Station Tutuila was completed in 1902. The station commander doubled as American Samoa’s Governor from 1899 to 1905, when the station commandant was designated Naval Governor of American Samoa. The Fono (legislature) served as an advisory council to the governor.[24]

Pago Pago became the administrative capital of American Samoa in 1899.[25][26]

20th century

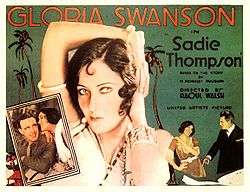

Early in December 1916, English author W. Somerset Maugham and his secretary Gerald Haxton decided to visit Pago Pago on their way from Hawai'i to Tahiti. Delayed because of a quarantine inspection, they checked into what is now known as Sadie Thompson Inn. He later released the popular short story, Rain (1921), which is a story of a prostitute arriving in Pago Pago. Maugham also met an American sailor here, which would later turn up as the title character in another short story, Red (1921).[25][27] The historic hotel where Maugham resided is Sadie Thompson Inn, which was added to the U.S. National Register of Historic Places in 2003. W. Somerset Maugham visited Pago Pago from December 16, 1916 to January 30, 1917. On board the ship was also a passenger named Miss Sadie Thompson, a lady who had been evicted from Hawaii for prostitution. She would later turn up as the main character in Rain.[28]

It was a vital naval base for the U.S. during World War II.[29] Limited improvements at the naval station took place in the summer of 1940, which included a Marine airfield at Tafuna. The new airfield was partly operational by April 1942, and fully operational by June. On March 15, 1941, the Marine Corps’ 7th Defense Battalion arrived in Pago Pago and was the first Fleet Marine Force unit to serve in the South Pacific Ocean. It was also the first such unit to be deployed in defense of an American island. Guns were emplaced at Blunt’s- and Breaker’s Points, covering Pago Pago Harbor. It trained the only Marine reserve unit to serve on active duty during World War II, namely the 1st Samoan Battalion, U.S. Marine Corps Reserve. The battalion mobilized after the attack on Pearl Harbor and remained active until January 1944.[30]

In January 1942 Pago Pago Harbor was shelled by a Japanese submarine, but this remained the only battle action on the islands during World War II.[31]

Pago Pago and the U.S. Naval Station was visited by First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt on August 24, 1943.[32][33]

It was an important location for NASA’s Apollo program in 1961–72. Apollo 10, Apollo 11, Apollo 12, Apollo 13, Apollo 14 and Apollo 17 landed by Tutuila Island, and the crew flew from Pago Pago to Honolulu on their way back to the mainland.[34][35] At Jean P. Haydon Museum are displays of an American Samoa-flag brought to the moon in 1969 by Apollo 11, as well as moon stones, all given as a gift to American Samoa by President Richard Nixon following the return of the Apollo moon missions.[36]

President Lyndon B. Johnson and First Lady Lady Bird Johnson visited Pago Pago on October 18, 1966. Johnson remains the only U.S. President who has visited American Samoa. Lyndon B. Johnson Tropical Medical Center was named in honor of the president.[37][38]

In November 1970, Pope Paul VI visited Pago Pago on his way to Australia.[39]

Mike Pence was the third sitting U.S. Vice President to visit American Samoa[40] when he made a stopover in Pago Pago in April 2017.[41] He addressed 200 soldiers here during his refueling stop.[42] U.S. Secretary of State, Rex Tillerson, visited town on June 3, 2017.[43]

2009 tsunami

On September 29, 2009, an earthquake struck in the South Pacific, near Samoa and American Samoa, sending a tsunami into Pago Pago and surrounding areas. The tsunami caused moderate to severe damage to villages, buildings and vehicles and caused 34 deaths.[44][45] It was an 8.3 magnitude earthquake which caused 5-feet waves to hit the city. It caused major flooding and damaged numerous buildings. Over 30 people were killed and hundreds were injured. A local power plant was disabled, 241 homes were destroyed, and 308 homes had major damage. Shortly after the earthquake, President Barack Obama issued a federal disaster declaration, which authorized funds for individual assistance (IA), such as temporary housing.[46]

The largest wave hit Pago Pago at 6:13 pm local time, which was a wave with an amplitude of 6.5 feet.[47]

Geography

The city of Pago Pago encompasses several surrounding villages,[48] including Fagatogo, the legislative and judicial capital, and Utulei, the executive capital and home of the Governor.[25] The town is located between steep mountainsides and the harbor. It is surrounded by mountains such as Mount Alava, Mount Matafao and Rainmaker Mountain, all mountains protecting Pago Pago Harbor.[49] The main downtown area is Fagatogo on the south shore of Pago Pago Harbor, the location of the Fono (territorial legislature), the port, the bus station and the market. The banks are in Utulei and Fagotogo, as are the Sadie Thompson Inn and other hotels. The tuna canneries, which provide employment for a third of the population of Tutuila, are in Atu'u on the north shore of the harbor. The village of Pago Pago is at the western head of the harbor.[50]

Pago Pago Harbor nearly bisects Tutuila Island. It is facing south and situated almost midpoint on the island. Its bay is 0.6 miles wide and 2.5 mi long. A 1,630 feet high mountain, Mount Pioa (Rainmaker Mountain), is located at the east side of the bay. The town is centered around the mouth of the Vaopito stream. Half of American Samoa’s inhabitants live along Pago Pago’s foothills and coastal areas. The downtown area is known as Fagatogo and is home to government offices, port facilities, Samoan High School and the Rainmaker Hotel. Two tuna factories are located in the northern part of town.[13]

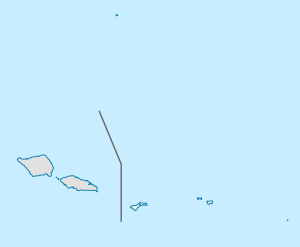

Pago Pago is in the Eastern District of American Samoa, in Ma'oputasi County.[51] It is approximately 2,600 miles southwest of Hawai'i, 1,600 miles northeast of New Zealand, and 4,500 miles southwest of California.[52] It is located at 14°16′46″S 170°42′02″W / 14.27944°S 170.70056°W. Pago Pago is located 18 degrees south of the equator.[53]

The north-central part of town is blanketed by the National Park of American Samoa.[54] A climb to the summit of Mt. Alava in the National Park of American Samoa provides a bird's-eye view of the harbor and town.[55]

City features

The Greater Pago Pago Area stretches into neighboring villages:[16]

- Fagatogo is home to the Pago Pago Post Office, museum, movie theater, bars and taxi services. It is locally known as Downtown Pago Pago.[56]

- Utelei and Maleimi are home to some Pago Pago-based hotels.

- Satala and Atu'u are home to Pago Pago’s tuna industry.

- Tafuna is the location of the Pago Pago International Airport, 7 miles south of Pago Pago.

Some houses are Western-style, other are more traditional Samoan housing units. All houses have running water and plumbing.[57]

Pago Pago Park is a public park by the harbor in Pago Pago. It lies by the Laolao Stream at the very end of Pago Pago Harbor. It is a 20-acre recreational complex and culture center. It is also home to the 10,000 capacity Veterans Memorial Stadium. There are also a ball field, sports court and boat ramp in the park. The park houses businesses such as the American Samoa Development Bank.[58][59]

National Park

Pago Pago is the primary entry point for visits to National Park of American Samoa, and the city is situated immediately south of the park.[3] Its park visitor center is located at the head of Pago Pago Harbor: Pago Plaza Visitor Center (Pago Plaza, Suite 114, Pago Pago, AS 96799).[61][62] This center also contains a collection of Samoan artifacts, corals, and seashells.[63] The nearest hotels to the national park are also located in Pago Pago.[64] Other parts of the park, on the islands of Ta‘ū and Ofu, can be visited via commercial inter-island air carrier from Pago Pago International Airport.

The national park is home to tropical rainforest, tall mountains, beaches, and some of the tallest sea cliffs in the world (3,000 ft).[65] It was authorized by the U.S. Congress in 1988 to preserve the paleotropical rain forest, Indo-Pacific coral reefs, and Samoan culture. It officially opened in 1993 when a 50-year lease was signed between the U.S. federal government, the government of American Samoa, and local village chiefs (Matai). It is the only U.S. National Park where the U.S. federal government leases the land from local residents instead of being the land owner. It is a 10,500-acre park which provides habitat for a variety of tropical wildlife, including coral reef fish, seabirds, flying fruit bats, and numerous other species of animals. The park’s offshore coral reefs provide habitat for 1,000 species of coral reef- and pelagic fishes.[66] The park is home to over 150 species of coral. Notable terrestrial species are the Pacific boa and the Flying Megabat, which has a three-foot-wingspread.[67]

Natural hazards

Pago Pago is vulnerable to natural- and man-made disasters. Vulnerabilities include heavy storms, flooding, tsunamis, mudslides, and earthquakes. American Samoa has experienced several cyclones and tropical storms, which also increase risks of rock slides and floodings.[68]

Climate

Pago Pago has a tropical rainforest (Köppen climate classification Af) climate. All official climate records for American Samoa are kept at Pago Pago. The hottest temperature ever recorded was 99 °F (37 °C) on February 22, 1958. Conversely, the lowest temperature on record was 59 °F (15 °C) on October 10, 1964.[69] The average annual temperature recorded at the weather station at Pago Pago International Airport is 80 degrees, with an average relative humidity of 80 percent. A temperature range of about three degrees Fahrenheit separates the average monthly temperatures of the coolest and hottest months.[70]

Pago Pago has been named one of the wettest places on Earth. It receives 119 inches (302 cm) of rain per year. The rainy season lasts from November through April, but the town experiences warm and humid temperatures year-round.[71] Besides its being wetter and more humid from November–April, this is also the hurricane season. The frequency of hurricanes hitting Pago Pago has increased dramatically in recent years. The windy season lasts from May to October. As warmer easterlies are forced up and over Rainmaker Mountain, clouds form and drop moisture on the city. Consequentially, Pago Pago experiences twice the rainfall of nearby Apia in the country of Samoa.[72] Rainmaker Mountain, which is also known as Mount Pioa, is a designated National Natural Landmark.[3]

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Record high °F (°C) | 95 (35) |

99 (37) |

95 (35) |

95 (35) |

93 (34) |

95 (35) |

91 (33) |

92 (33) |

92 (33) |

94 (34) |

95 (35) |

94 (34) |

99 (37) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 87.6 (30.9) |

88.0 (31.1) |

88.1 (31.2) |

87.5 (30.8) |

86.2 (30.1) |

85.0 (29.4) |

84.2 (29) |

84.3 (29.1) |

85.3 (29.6) |

85.8 (29.9) |

86.6 (30.3) |

87.4 (30.8) |

86.3 (30.2) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 82.6 (28.1) |

82.9 (28.3) |

82.9 (28.3) |

82.5 (28.1) |

81.8 (27.7) |

81.1 (27.3) |

80.4 (26.9) |

80.4 (26.9) |

81.1 (27.3) |

81.5 (27.5) |

82.1 (27.8) |

82.5 (28.1) |

81.8 (27.7) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 77.6 (25.3) |

77.7 (25.4) |

77.8 (25.4) |

77.6 (25.3) |

77.5 (25.3) |

77.1 (25.1) |

76.6 (24.8) |

76.5 (24.7) |

76.9 (24.9) |

77.2 (25.1) |

77.5 (25.3) |

77.6 (25.3) |

77.3 (25.2) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 67 (19) |

65 (18) |

63 (17) |

68 (20) |

65 (18) |

61 (16) |

62 (17) |

60 (16) |

62 (17) |

59 (15) |

60 (16) |

65 (18) |

59 (15) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 14.83 (376.7) |

12.66 (321.6) |

11.66 (296.2) |

11.02 (279.9) |

10.61 (269.5) |

6.01 (152.7) |

6.46 (164.1) |

6.30 (160) |

7.62 (193.5) |

10.11 (256.8) |

11.30 (287) |

14.51 (368.6) |

123.09 (3,126.5) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 24.0 | 21.4 | 23.8 | 22.1 | 20.1 | 19.1 | 19.3 | 17.8 | 17.9 | 20.9 | 20.8 | 23.1 | 250.2 |

| Source: NOAA (normals)[69] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

The village of Pago Pago proper had a 2010 population of 3,656. However, Pago Pago also encompasses neighboring villages. The Greater Pago Pago Area was home to 11,500 residents in 2011.[73] Around 90 percent of American Samoa’s population lives around Pago Pago.[74][75]

As of the 2000 U.S. Census, 74.5% of Pago Pago’s population are of Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Island race. 16.6% were Asian, while 4.9% were white.[76]

Government

Pago Pago is the seat of the judiciary (Fagatogo), legislature and Governor’s Office (Utulei).[16]

Education

The Feleti Barstow Public Library is located in Pago Pago.[77] In 1991, severe tropical cyclone Val hit Pago Pago, destroying the library that existed there. The current Barstow library, constructed in 1998, opened on April 17, 2000.[78]

Economy

Tuna canning is the main economic activity in town. Exports are almost exclusively tuna canneries such as Chicken of the Sea and StarKist, which are both located in Pago Pago. These also occupy 14 percent of American Samoa’s total work force as of 2014.[79] The most industrialized area in the territory can be found between Pago Pago Harbor and the Tafuna-Leone Plain, which also are the two most densely populated places in the islands.

American Samoa was the world’s fourth-largest tuna processor in 1993. The primary industry is tuna processing by the Samoa Packing Co. (Chicken of the Sea) and StarKist Samoa, a subsidiary of H.J. Heinz. The first cannery was opened in 1954. Canned fish, canned pet food, and fish meal from skin and bones account for 93 percent of American Samoa’s industrial output.[9]

Centers for shopping are Pago Plaza, which consists of smaller stores selling handcrafts and souvenirs, and Fagatogo Square Shopping Center, which is home to larger shops.[48] This shopping mall is next-door to Fagatogo Market in Fagatogo, which is considered the main center of Pago Pago. It is home to several restaurants, shops, bars, and often live entertainment and music. Souvenirs are often sold at the market when cruise ships are visiting town. Locals also sell handmade crafts at the dock and on main street. Mount Alava, the canneries in Atu'u, Rainmaker Mountain (Mount Pioa), and Pago Pago Harbor are all visible from the market. The main bus station is located immediately behind the market.[80][81]

It is a wealthier city than nearby Apia, capital of Samoa.[82][83][84]

Tourism

Tourism in American Samoa is centered around Pago Pago. It receives 34,000 visitors per year, which is one-fourth of neighboring country of Samoa. 69.3 percent of visitors are from the United States as of 2014.[85]

Until 1980, one could experience the view of Mt. Avala by taking an aerial tramway over the harbor, but on April 17 of that year a U.S. Navy plane, flying overhead as part of the Flag Day celebrations, struck the cable; the plane crashed into a wing of the Rainmaker Hotel.[86] The tramway was repaired, but closed not long after. The tram remains unusable, although according to Lonely Planet, plans have been put forth to reopen it, but in December 2010 the cable was damaged by Tropical Cyclone Wilma, fell into the harbor and has not been repaired. Governor Lolo Matalasi Moliga announced in 2014 that he would look into restoring the cable car.[87]

Another noted view is that from the top of the pass above Aua Village on the road to Afono.

The Sadie Thompson Inn, on the outskirts of Pago Pago, is a hotel and restaurant that is listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places.

The Greater Pago Pago Area is home to more than 10 hotels:[88]

- Rainmaker Hotel, the largest hotel on Tutuila Island

- Quality Inn Tradewinds Hotel, located by the airport at Ottoville

- Sadie Thompson Inn, named for a character in Rain (1921), in Fagatogo

- Herb and Sia’s Motel, in downtown area of Fagatogo

- Scanlan Inn, a smaller motel in Fagatogo

- Motu O Fiafiaga Motel, in Fagatogo

- Sadies by the Sea, hotel in 'Utulei

Transportation

Pago Pago Harbor is the port of entry for vessels arriving in American Samoa.[92] Many cruise boats and ships land at Pago Pago Harbor for reprovision reasons, such as to restock on goods and to utilize American-trained medical personnel.[93] Pago Pago Harbor is one of the world’s largest natural harbors.[73] It has been named one of the best deepwater harbors in the South Pacific Ocean,[4][94] or one of the best in the world as a whole.[95]

Pago Pago is a popular port of call for South Pacific cruise ships, including Norwegian Cruise Line[96] and Princess Cruises.[97] However, cruise ships do not take on passengers in Pago Pago, but typically arrive in the morning and depart in the afternoon. Thirteen cruise ships were scheduled to visit Pago Pago in 2017, bringing 31,000 visitors.[98] Pago Pago Harbor can accommodate two cruise ships at the same time, and has done so on several occasions.[99]

Pago Pago International Airport is located at Tafuna, 8 miles southwest of Pago Pago. Polynesian Airlines operates shuttles between Apia and Pago Pago 4-7 times daily. Most flights are to and from Fagali'i.[100] Of the 88,650 international arrivals in 2001, only 10 percent were tourists. The rest came to visit relatives, for employment reasons, or in transit. Most international visitors are from the independent country of Samoa.[101] There are international flights to Samoa from Pago Pago International Airport (PPG):[53] Pago Pago is a 35-minute flight from Apia in Samoa.[102] There is only one flight destination from the territory to the United States: Honolulu International Airport, a five-hour flight from Pago Pago. Scheduled intra-territorial flights are available to the islands of Ta‘ū and Ofu, which take 30 minutes by air from Pago Pago.

A ship called MV Lady Naomi runs between Pago Pago and Apia, the capital of Samoa, once a week.

Landmarks

- National Park of American Samoa, immediately north of town

- Government House is a colonial mansion atop Mauga o Ali'i (the chief’s hill), which was erected in 1903

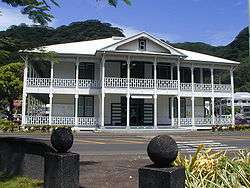

- The Fono is the territorial legislature

- The Courthouse is a two-story colonial-style house listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places

- The Aerial Tramway at Mount Alava is one of the world’s longest single-span cablecar routes.[106] It begins atop Solo Hill at the end of the Togotogo Ridge above ‘Utulei. It ascends 1.1 miles (1.8 kilometers) across Pago Pago Harbor and lands at the 1,598 ft (487 m) Mount ‘Alava. It was constructed in 1965 as an access to the TV transmission equipment on the mountain.

- Jean P. Haydon Museum was constructed in 1917 and houses historical artifacts such as canoes. It is named for its founder, the wife of Governor John Morse Haydon

- Blunts Point Battery, erected as a part of the fortification following the attack on Pearl Harbor[107]

- Rainmaker Mountain (Pioa Mountain), designated National Natural Landmark[3]

- Lyndon B. Johnson Tropical Medicine Center

- Utulei Beach, beach in 'Utulei

In popular culture

- Rain (1921) by W. Somerset Maugham is set in Pago Pago.[109][110] Movie adaptions include Sadie Thompson (1928), Rain (1932), and Miss Sadie Thompson (1953).

- The Blonde Captive (1931) was filmed in Pago Pago.[111]

- The Hurricane (1937) and its sequel, Hurricane (1979), were set in Pago Pago. The 1937 film was filmed in Pago Pago.[111]

- The storyline in the film South of Pago Pago (1940) is set here. This movie was partly shot in Pago Pago, although most filming took place in Hawai'i and Long Beach, CA.[112]

- A jungle village resembling Pago Pago was created for motion picture in Two Harbors, Catalina Island, CA.[113] Several Sadie Thompson films were shot here.

- Lost and Found on a South Sea Island (1923) is set in Pago Pago.

- Next Goal Wins (2014), British documentary filmed in Pago Pago.

- Samoa, California was named in honor of American Samoa. It was assumed that the harbor in Pago Pago looked similar to that of the town, and it consequentially got the name Samoa, CA in the 1890s.[114]

- In the Sweet Pie and Pie (1941), The Three Stooges short. Pago Pago is mentioned as being one of the locations for the fictional Heedam Neckties stores.

Notable people

- Peter Tali Coleman, 43rd, 51st, and 53rd Governor of American Samoa

- Al Harrington, actor most known for his role in Hawaii Five-O[115]

- Gary Scott Thompson, director and television producer[116]

- John Kneubuhl, screenwriter

- Shalom Luani, NFL-player for Oakland Raiders

- Junior Siavii, NFL-player

- Jonathan Fanene, NFL-player

- Mosi Tatupu, NFL-player

- Shaun Nua, NFL-player for the Pittsburgh Steelers

- Isaac Sopoaga, NFL-player for San Francisco 49ers

- Daniel Te’o-Nesheim, NFL-player for Philadelphia Eagles

- Kennedy Polamalu, football coach

- Frank Solomon, rugby player

- Faauuga Muagututia, US Navy Seal

- Amata Coleman Radewagen, current Delegate in the U.S. House of Representatives

See also

References

- ↑ United States Postal Service (2012). "USPS - Look Up a ZIP Code". Retrieved February 15, 2012.

- ↑ "Geographic Names Information System". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 Harris, Ann G. and Esther Tuttle (2004). Geology of National Parks. Kendall Hunt. Page 604. ISBN 9780787299705.

- 1 2 United States Central Intelligence Agency (2016). The World Factbook 2016–17. Government Printing Office. Page 19. ISBN 9780160933271.

- ↑ Grabowski, John F. (1992). U.S. Territories and Possessions (State Report Series). Chelsea House Pub. Page 52. ISBN 9780791010532.

- ↑ Kristen, Katherine (1999). Pacific Islands (Portrait of America). San Val. Page 12. ISBN 9780613032421.

- ↑ Leonard, Barry (2009). Minimum Wage in American Samoa 2007: Economic Report. Diane Publishing. Page 11. ISBN 9781437914252.

- ↑ Leonard, Barry (2009). Minimum Wage in American Samoa 2007: Economic Report. Diane Publishing. Page 61. ISBN 9781437914252.

- 1 2 Stanley, David (1993). South Pacific Handbook. David Stanley. Page 353. ISBN 9780918373991.

- ↑ Smith, Andrew F. (2012). American Tuna: The Rise and Fall of an Improbable Food. University of California Press. Page 164. ISBN 9780520954151.

- ↑ Kristen, Katherine (1999). Pacific Islands (Portrait of America). San Val. Page 29. ISBN 9780613032421.

- ↑ Mack, Doug (2017). The Not-Quite States of America: Dispatches From the Territories and Other Far-Flung Outposts of the USA. W.W. Norton & Company. Page 62. ISBN 9780393247602.

- 1 2 Lal, Brij V. and Kate Fortune (2000). The Pacific Islands: An Encyclopedia, Volume 1. University of Hawaii Press. Page 101. ISBN 9780824822651.

- 1 2 Lonely Planet. "Rainmaker Mountain in Tutuila". Lonely Planet. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- ↑ "American Samoa Is The Empty Slice Of Bliss You've Been Craving". huffingtonpost.com. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- 1 2 3 Cruise Travel Vol. 2, No. 1 (July 1980). Lakeside Publishing Co. Page 60. ISSN 0199-5111.

- ↑ "Uber, schmuber. Behold the buses of Pago Pago ..." LA Times. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- ↑ Stahl, Dean A. and Karen Landen (2001). Abbreviations Dictionary. CRC Press. Page 1451. ISBN 9781420036640.

- ↑ Freeman, Donald B. (2010). The Pacific. Routledge. Page 167. ISBN 9780415775724.

- ↑ Levi, Werner (1947). American-Australian Relations. University of Minnesota Press. Page 73. ISBN 9780816658152.

- ↑ Dixon, Joe C. (1980). The American Military and the Far East. Diane Publishing. Page 139. ISBN 9781428993679.

- ↑ Stanley, George Edwards (2005). The Era of Reconstruction and Expansion (1865–1900). Gareth Stevens. Page 36. ISBN 9780836858273.

- ↑ Pafford, John (2013). The Forgotten Conservative: Rediscovering Grover Cleveland. Regnery Publishing. Page 61. ISBN 9781621570554.

- ↑ Rottman, Gordon L. (2002). World War II Pacific Island Guide: A Geo-military Study. Greenwood Publishing Group. Pages 84-85. ISBN 9780313313950.

- 1 2 3 "Pago Pago | American Samoa". Britannica.com. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- ↑ Carpenter, Allan (1993). Facts about the Cities. Wilson. Page 11. ISBN 9780924208003.

- ↑ Rogal, Samuel J. (1997). A William Somerset Maugham Encyclopedia. Greenwood Publishing Group. Page 244. ISBN 9780313299162.

- ↑ "NFS Form 10-900-a OMB Approval No. 1024-0018 | Thompson, Sadie, Building, Eastern AS" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places. February 2, 2009. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- ↑ Labor, Earle (2013). Jack London: An American Life. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Page 272. ISBN 9781466863163.

- ↑ Rottman, Gordon L. (2002). World War II Pacific Island Guide: A Geo-military Study. Greenwood Publishing Group. Pages 85-86. ISBN 9780313313950.

- ↑ Rill, James C. (2003). A Narrative History of the 1st Battalion, 11th Marines During the Early History and Deployment of the 1st Marine Division, 1940–43. Merriam Press. Page 32. ISBN 9781576383179.

- ↑ "David Huebner - US Ambassador to New Zealand". web.archive.org. Archived from the original on February 27, 2013. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- ↑ "samoanews.com/local-news/dedication-va-clinic-centerpiece-vp-pence-visit-amsam". samoanews.com. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- ↑ "Apollo At American Samoa Summary". members.tripod.com. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- ↑ "Kevin Steen". history.nasa.gov. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- ↑ "Jean P. Haydon Museum Review | Fodor's Travel". fodors.com. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- ↑ "Lyndon B. Johnson: Remarks Upon Arrival at Tafuna International Airport, Pago Pago, American Samoa". presidency.ucsb.edu. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- ↑ "1968 Annual Report: American Samoa" (PDF). July 22, 2011. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- ↑ Cassidy, Edward Idris (2009). My Years in Vatican Service. Paulist Press. Page 52. ISBN 9780809145935.

- ↑ http://www.radionz.co.nz/international/pacific-news/329073/us-vice-president-to-dedicate-american-samoa-clinic-to-'eni’

- ↑ "Pence cutting Pacific trip short". POLITICO. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- ↑ "Mike Pence cuts short his stop in Hawaii to deal with domestic issues". CBS News. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- ↑ "american samoa". americansamoa.gov. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- ↑ Article on Google News

- ↑ "Disaster aid flows to tsunami-hit Samoas". MSNBC.

- ↑ Jadacki, Matt (2011). American Samoa 2009 Earthquake and Tsunami: After-Action Report. DIANE Publishing. Page 2. ISBN 9781437942835.

- ↑ Dunbar, Paula K. (2015). Pacific Tsunami Warning System: A Half Century of Protecting the Pacific, 1965–2015. Government Printing Office. Page 56. ISBN 9780996257909.

- 1 2 "Pago Pago, American Samoa: The Capital City on the Harbor". visittheusa.com. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- ↑ "Port of Pago Pago - American Samoa | Department of Port Administration". americansamoaport.as.gov. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- ↑ "Pago Pago (American Samoa)". Britannica Online Encyclopedia.

- ↑ https://www.census.gov/population/www/cen2010/cph-t/t-8tables/table1b.pdf (Page 2).

- ↑ Ruffner, James A. and Frank E. Bair (1987). Weather of U.S. Cities: City Reports. Gale Research Company. Page 840. ISBN 9780810321021.

- 1 2 "Pago Pago International Airport (PPG) - American Samoa | Department of Port Administration". americansamoaport.as.gov. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- ↑ "Pago Pago, capital city of American Samoa". visitcapitalcity.com. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- ↑ Farrell, Jack, "American Samoa American Samoa: A Tropical Delight Hosting the Only U.S. National Park South of the Equator", Frederick News-Post, Sunday, March 16, 2014

- ↑ Grabowski, John F. (1992). U.S. Territories and Possessions (State Report Series). Chelsea House Pub. Page 51. ISBN 9780791010532.

- ↑ McDonald, George (1994). Frommer's Guide to the South Pacific, 1994–1995. Prentice Hall Travel. Page 262. ISBN 9780671866600.

- ↑ Goodwin, Geoge McDonald (1994). Frommer’s Guide to the South Pacific, 1994–1995. Prentice Hall Travel. Page 258. ISBN 9780671866600.

- ↑ Lonely Planet Publications (1990). Samoa, Western & American Samoa. Lonely Planet Publications. Page 141. ISBN 9780864420787.

- ↑ National Geographic (2016). National Geographic Guide to National Parks of the United States. National Geographic. Page 319. ISBN 9781426216510.

- ↑ National Geographic Society (2012). National Geographic Guide to National Parks of the United States. National Geographic Books. Page 233. ISBN 9781426208690.

- ↑ Smith, Darren L. and Penny J. Hoffman (2001). Parks Directory of the United States. Omnigraphics. Page 70. ISBN 9780780804401.

- ↑ Stanley, David (2004). Moon Handbooks South Pacific. David Stanley. Page 479. ISBN 9781566914116.

- ↑ Moker, Molly (2008). America's National Parks: Complete Coverage of All 391 National Parks, Including Scenic Trails, Battlefields, and Other Historic Sites. Fodor's Travel Pub. Page 429. ISBN 9781400016280.

- ↑ Harris, Ann G. and Esther Tuttle (2004). Geology of National Parks. Kendall Hunt. Page 603. ISBN 9780787299705.

- ↑ Goldin, Meryl Rose (2002). Field Guide to the Sāmoan Archipelago: Fish, Wildlife, and Protected Areas. Bess Press. Pages 273-274. ISBN 9781573061117.

- ↑ Butcher, Russell D. and Lynn P. Whitaker (1999). National Parks and Conservation Association Guide to National Parks: Pacific Region. Globe Pequot Press. Page 82. ISBN 9780762705733.

- ↑ Corlew, Kati (2015). Sauniuniga mo Puapuaga ma Suiga o le Tau i Amerika Sāmoa (in Samoan language). East-West Center. Pages 3-5. ISBN 9780866382601.

- 1 2 "NOWData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved November 22, 2012.

- ↑ U.S. National Park Service (1997). National Park of American Samoa, General Management Plan (GP), Islands of Tutulla, Ta'u, and Ofu: Environmental Impact Statement. United States National Park Service. Page 102.

- ↑ Rustad, Martha E. (2010). The Wettest Places on Earth. Capstone. Page 6. ISBN 9781429639668.

- ↑ Stanley, David (1993). South Pacific Handbook. David Stanley. Pages 350-351. ISBN 9780918373991.

- 1 2 https://ngdc.noaa.gov/mgg/coastal/pacific_islands_dem_catalog.pdf

- ↑ McColl, R.W. (2014). Encyclopedia of World Geography, Volume 1. Infobase Publishing. Page 29. ISBN 9780816072293.

- ↑ "library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/print_aq". cia.gov. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- ↑ Census of population and housing (2000): American Samoa Summary Social, Economic, and Housing Characteristics (2000). DIANE Publishing. Page 147. ISBN 9781428985490.

- ↑ "Contact Us". Feleti Barstow Public Library. Retrieved May 19, 2010.

- ↑ "History." Feleti Barstow Public Library. Retrieved May 19, 2010.

- ↑ http://www.gao.gov/assets/690/681370.pdf (Page 1)

- ↑ Lonely Planet. "Fagatogo Market in Tutuila". Lonely Planet. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- ↑ Stanley, David (1999). Moon Handbooks Tonga-Samoa. David Stanley. Page 168. ISBN 9781566911740.

- ↑ Brillat, Michael (1999). South Pacific Islands. Hunter Publishing, Inc. Page 136. ISBN 9783886181049.

- ↑ "AGING WELL IN AMERICAN SAMOA". The New York Times. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- ↑ Goodwin, George McDonald (1994). Frommer's Guide to the South Pacific, 1994–1995. Prentice Hall Travel. Page 205. ISBN 9780671866600.

- ↑ Harssel, Jan van and Richard H. Jackson (2014). National Geographic Learning's Visual Geography of Travel and Tourism. Cengage Learning. Page 526. ISBN 9781305176478.

- ↑ Moos, Grant. 1980 [1997]. "April 17, 1980: Fiery crash halts Flag Day". Samoa News, April 18, 1980 (reprinted in the Samoa News, January 22, 1997: 4). Cited in Sorensen, Stan, and Joseph Theroux. The Samoan Historical Calendar, 1606–2007 Archived 2009-02-27 at the Wayback Machine.. p. 93.

- ↑ "American Samoa plans cable car revival". Radio New Zealand News. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- ↑ Stanley, David (2004). Moon Handbooks South Pacific. David Stanley. Pages 483-485. ISBN 9781566914116.

- ↑ "Pago Pago Harbor, American Samoa". American Samoa Tourism. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- ↑ "American Samoa Targets Expedition Market - Cruise Industry News | Cruise News". cruiseindustrynews.com. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- ↑ "American Samoa Cruises". USA Today. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- ↑ Stanley, David (1999). South Pacific Handbook. Moon Handbooks. Page 438. ISBN 9781566911726.

- ↑ Pocock, Michael (2013). The Pacific Crossing Guide: RCC Pilotage Foundation with Ocean Cruising Club. Bloomsbury Publishing. Page 71. ISBN 9781472905260.

- ↑ McColl, R.W. (2014). Encyclopedia of World Geography, Volume 1. Infobase Publishing. Page 28. ISBN 9780816072293.

- ↑ Creason, Pam (1993). Geography. Page 588. ISBN 9780890843772.

- ↑ "Welcome". ncl.com. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- ↑ "Princess Cruises : Pago Pago, American Samoa". princess.com. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- ↑ "Thirteen cruise ships to visit American Samoa". Radio New Zealand News. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- ↑ "American Samoa Targets Expedition Market - Cruise Industry News | Cruise News". cruiseindustrynews.com. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- ↑ Stanley, David (2004). Moon Handbooks South Pacific. David Stanley. Page 512. ISBN 9781566914116.

- ↑ Stanley, David (2004). Moon Handbooks South Pacific. David Stanley. Pages 468-469. ISBN 9781566914116.

- ↑ "Port Information - American Samoa | Department of Port Administration". americansamoaport.as.gov. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- ↑ "Planning a Trip in American Samoa | Frommer's". frommers.com. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- ↑ Grabowski, John F. (1992). U.S. Territories and Possessions (State Report Series). Chelsea House Pub. Page 54. ISBN 9780791010532.

- ↑ Swaney, Deanna (1994). Samoa: Western & American Samoa: a Lonely Planet Travel Survival Kit. Lonely Planet Publications. Pages 167-169. ISBN 9780864422255.

- ↑ Swaney, Deanna (1994). Samoa: Western & American Samoa: a Lonely Planet Travel Survival Kit. Lonely Planet Publications. Page 167. ISBN 9780864422255.

- ↑ "american samoa". americansamoa.gov. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- ↑ Moss, Marilyn (2011). Raoul Walsh: The True Adventures of Hollywood's Legendary Director. University Press of Kentucky. Page 101. ISBN 9780813133942.

- ↑ Stanley, David (2004). Moon Handbooks South Pacific. David Stanley. Page 463. ISBN 9781566914116.

- ↑ Cruise Travel Vol. 2, No. 1 (July 1980). Lakeside Publishing Co. Page 61. ISSN 0199-5111.

- 1 2 American Film Institute (1993). The American Film Institute Catalog of Motion Pictures Produced in the United States, Volume 1. University of California Press. Page 1111. ISBN 9780520079083.

- ↑ Reyes, Luis and Ed Rampell (1995). Made in paradise: Hollywood's films of Hawai'i and the South Seas. Mutual Pub. Page 1940. ISBN 9781566470896.

- ↑ Fleming, E.J. (2008). Paul Bern: The Life and Famous Death of the MGM Director and Husband of Harlow. McFarland. Page 73. ISBN 9780786452743.

- ↑ Capace, Nancy (1999). Encyclopedia of California. North American Book Dist LLC. Page 399. ISBN 9780403093182.

- ↑ Hunter, James Michael (2013). Mormons and Popular Culture: The Global Influence of an American Phenomenon. Literature, art, media, tourism, and sports. Volume 2. ABC-CLIO. Page 237. ISBN 9780313391675.

- ↑ "About". gstproductions.com. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pago Pago. |

- Pago Pago, American Samoa National Weather Service Office

- Pago Pago Weather underground

- Census-2010 Population

Coordinates: 14°16′46″S 170°42′02″W / 14.27944°S 170.70056°W