New Jersey

| State of New Jersey | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Nickname(s): The Garden State[1] | |||||

| Motto(s): Liberty and prosperity | |||||

| |||||

| Official language | None | ||||

| Spoken languages | |||||

| Demonym | New Jerseyan (official),[3] New Jerseyite[4][5] | ||||

| Capital | Trenton | ||||

| Largest city | Newark | ||||

| Largest metro | Greater New York | ||||

| Area | Ranked 47th | ||||

| • Total |

8,722.58 sq mi (22,591.38 km2) | ||||

| • Width | 70 miles (112 km) | ||||

| • Length | 170 miles (273 km) | ||||

| • % water | 15.7 | ||||

| • Latitude | 38° 56′ N to 41° 21′ N | ||||

| • Longitude | 73° 54′ W to 75° 34′ W | ||||

| Population | Ranked 11th | ||||

| • Total | 9,032,872 (2018 est.)[6] | ||||

| • Density |

1210.10/sq mi (467/km2) Ranked 1st | ||||

| • Median household income | $68,357[7] (7th) | ||||

| Elevation | |||||

| • Highest point |

High Point[8][9] 1,803 ft (549.6 m) | ||||

| • Mean | 250 ft (80 m) | ||||

| • Lowest point |

Atlantic Ocean[8] Sea level | ||||

| Before statehood | Province of New Jersey | ||||

| Admission to Union | December 18, 1787 (3rd) | ||||

| Governor | Phil Murphy (D) | ||||

| Lieutenant Governor | Sheila Oliver (D) | ||||

| Legislature | New Jersey Legislature | ||||

| • Upper house | Senate | ||||

| • Lower house | General Assembly | ||||

| U.S. Senators |

Bob Menendez (D) Cory Booker (D) | ||||

| U.S. House delegation |

7 Democrats 5 Republicans (list) | ||||

| Time zone | Eastern: UTC -5/-4 | ||||

| ISO 3166 | US-NJ | ||||

| Abbreviations | NJ, N.J. | ||||

| Website |

www | ||||

| New Jersey state symbols | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Living insignia | |

| Bird | Eastern goldfinch[10] |

| Fish | Brook trout[11] |

| Flower | Viola sororia[12] |

| Insect | Western honey bee[13] |

| Mammal | Horse[14] |

| Tree | Quercus rubra (northern red oak),[15] dogwood (memorial tree)[15] |

| Inanimate insignia | |

| Colors |

Buff and blue |

| Folk dance | Square dance[16] |

| Food | Northern highbush blueberry (state fruit)[17] |

| Fossil | Hadrosaurus foulkii[18] |

| Soil | Downer[19] |

| State route marker | |

| |

| State quarter | |

Released in 1999 | |

| Lists of United States state symbols | |

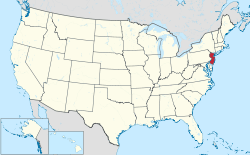

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the Northeastern United States. It is a peninsula, bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delaware River and Pennsylvania; and on the southwest by the Delaware Bay and Delaware. New Jersey is the fourth-smallest state by area but the 11th-most populous, with 9 million residents as of 2017,[20] and the most densely populated of the 50 U.S. states. New Jersey lies completely within the combined statistical areas of New York City and Philadelphia and is the third-wealthiest state by median household income as of 2016.[21]

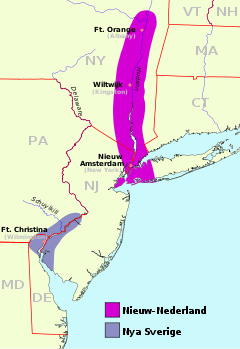

New Jersey was inhabited by Native Americans for more than 2,800 years, with historical tribes such as the Lenape along the coast. In the early 17th century, the Dutch and the Swedes made the first European settlements in the state.[22] The English later seized control of the region,[23] naming it the Province of New Jersey after the largest of the Channel Islands, Jersey,[24] and granting it as a colony to Sir George Carteret and John Berkeley, 1st Baron Berkeley of Stratton. New Jersey was the site of several decisive battles during the American Revolutionary War in the 18th century.

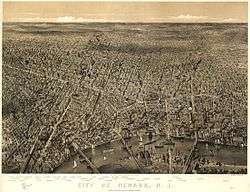

In the 19th century, factories in cities (known as the "Big Six"[25]), Camden, Paterson, Newark, Trenton, Jersey City, and Elizabeth helped to drive the Industrial Revolution. New Jersey's geographic location at the center of the Northeast megalopolis, between Boston and New York City to the northeast, and Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington, D.C., to the southwest, fueled its rapid growth through the process of suburbanization in the second half of the 20th century. In the first decades of the 21st century, this suburbanization began reverting with the consolidation of New Jersey's culturally diverse populace toward more urban settings within the state,[26][27] with towns home to commuter rail stations outpacing the population growth of more automobile-oriented suburbs since 2008.[28]

History

Around 180 million years ago, during the Jurassic Period, New Jersey bordered North Africa. The pressure of the collision between North America and Africa gave rise to the Appalachian Mountains. Around 18,000 years ago, the Ice Age resulted in glaciers that reached New Jersey. As the glaciers retreated, they left behind Lake Passaic, as well as many rivers, swamps, and gorges.[29]

New Jersey was originally settled by Native Americans, with the Lenni-Lenape being dominant at the time of contact. Scheyichbi is the Lenape name for the land that is now New Jersey.[30] The Lenape were several autonomous groups that practiced maize agriculture in order to supplement their hunting and gathering in the region surrounding the Delaware River, the lower Hudson River, and western Long Island Sound. The Lenape society was divided into matrilinear clans that were based upon common female ancestors. These clans were organized into three distinct phratries identified by their animal sign: Turtle, Turkey, and Wolf. They first encountered the Dutch in the early 17th century, and their primary relationship with the Europeans was through fur trade.

Colonial era

The Dutch became the first Europeans to lay claim to lands in New Jersey. The Dutch colony of New Netherland consisted of parts of modern Middle Atlantic states. Although the European principle of land ownership was not recognized by the Lenape, Dutch West India Company policy required its colonists to purchase the land that they settled. The first to do so was Michiel Pauw who established a patronship called Pavonia in 1630 along the North River which eventually became the Bergen. Peter Minuit's purchase of lands along the Delaware River established the colony of New Sweden. The entire region became a territory of England on June 24, 1664, after an English fleet under the command of Colonel Richard Nicolls sailed into what is today New York Harbor and took control of Fort Amsterdam, annexing the entire province.

During the English Civil War, the Channel Island of Jersey remained loyal to the British Crown and gave sanctuary to the King. It was from the Royal Square in Saint Helier that Charles II of England was proclaimed King in 1649, following the execution of his father, Charles I. The North American lands were divided by Charles II, who gave his brother, the Duke of York (later King James II), the region between New England and Maryland as a proprietary colony (as opposed to a royal colony). James then granted the land between the Hudson River and the Delaware River (the land that would become New Jersey) to two friends who had remained loyal through the English Civil War: Sir George Carteret and Lord Berkeley of Stratton.[31] The area was named the Province of New Jersey.

Since the state's inception, New Jersey has been characterized by ethnic and religious diversity. New England Congregationalists settled alongside Scots Presbyterians and Dutch Reformed migrants. While the majority of residents lived in towns with individual landholdings of 100 acres (40 ha), a few rich proprietors owned vast estates. English Quakers and Anglicans owned large landholdings. Unlike Plymouth Colony, Jamestown and other colonies, New Jersey was populated by a secondary wave of immigrants who came from other colonies instead of those who migrated directly from Europe. New Jersey remained agrarian and rural throughout the colonial era, and commercial farming developed sporadically. Some townships, such as Burlington on the Delaware River and Perth Amboy, emerged as important ports for shipping to New York City and Philadelphia. The colony's fertile lands and tolerant religious policy drew more settlers, and New Jersey's population had increased to 120,000 by 1775.

Settlement for the first 10 years of English rule took place along Hackensack River and Arthur Kill – settlers came primarily from New York and New England. On March 18, 1673, Berkeley sold his half of the colony to Quakers in England, who settled the Delaware Valley region as a Quaker colony. (William Penn acted as trustee for the lands for a time.) New Jersey was governed very briefly as two distinct provinces, East and West Jersey, for 28 years between 1674 and 1702, at times part of the Province of New York or Dominion of New England.

In 1702, the two provinces were reunited under a royal governor, rather than a proprietary one. Edward Hyde, Lord Cornbury, became the first governor of the colony as a royal colony. Britain believed that he was an ineffective and corrupt ruler, taking bribes and speculating on land. In 1708 he was recalled to England. New Jersey was then ruled by the governors of New York, but this infuriated the settlers of New Jersey, who accused those governors of favoritism to New York. Judge Lewis Morris led the case for a separate governor, and was appointed governor by King George II in 1738.[32]

Revolutionary War era

New Jersey was one of the Thirteen Colonies that revolted against British rule in the American Revolution. The New Jersey Constitution of 1776 was passed July 2, 1776, just two days before the Second Continental Congress declared American Independence from Great Britain. It was an act of the Provincial Congress, which made itself into the State Legislature. To reassure neutrals, it provided that it would become void if New Jersey reached reconciliation with Great Britain.

New Jersey representatives Richard Stockton, John Witherspoon, Francis Hopkinson, John Hart, and Abraham Clark were among those who signed the United States Declaration of Independence.

During the American Revolutionary War, British and American armies crossed New Jersey numerous times, and several pivotal battles took place in the state. Because of this, New Jersey today is often referred to as "The Crossroads of the American Revolution."[33] The winter quarters of the Continental Army were established there twice by General George Washington in Morristown, which has been called "The Military Capital of the American Revolution".[34]

On the night of December 25–26, 1776, the Continental Army under George Washington crossed the Delaware River. After the crossing, he surprised and defeated the Hessian troops in the Battle of Trenton. Slightly more than a week after victory at Trenton, American forces gained an important victory by stopping General Cornwallis's charges at the Second Battle of Trenton. By evading Cornwallis's army, Washington made a surprise attack on Princeton and successfully defeated the British forces there on January 3, 1777. Emanuel Leutze's painting of Washington Crossing the Delaware became an icon of the Revolution.

American forces under Washington met the forces under General Henry Clinton at the Battle of Monmouth in an indecisive engagement in June 1778. Washington attempted to take the British column by surprise; when the British army attempted to flank the Americans, the Americans retreated in disorder. The ranks were later reorganized and withstood the British charges.

In the summer of 1783, the Continental Congress met in Nassau Hall at Princeton University, making Princeton the nation's capital for four months. It was there that the Continental Congress learned of the signing of the Treaty of Paris (1783), which ended the war.

On December 18, 1787, New Jersey became the third state to ratify the United States Constitution, which was overwhelmingly popular in New Jersey, as it prevented New York and Pennsylvania from charging tariffs on goods imported from Europe. On November 20, 1789, the state became the first in the newly formed Union to ratify the Bill of Rights.

The 1776 New Jersey State Constitution gave the vote to "all inhabitants" who had a certain level of wealth. This included women and blacks, but not married women, because they could not own property separately from their husbands. Both sides, in several elections, claimed that the other side had had unqualified women vote and mocked them for use of "petticoat electors", whether entitled to vote or not; on the other hand, both parties passed Voting Rights Acts. In 1807, the legislature passed a bill interpreting the constitution to mean universal white male suffrage, excluding paupers; the constitution was itself an act of the legislature and not enshrined as the modern constitution.[35]

19th century

On February 15, 1804, New Jersey became the last northern state to abolish new slavery and enacted legislation that slowly phased out existing slavery. This led to a gradual decrease of the slave population. By the close of the Civil War, about a dozen African Americans in New Jersey were still held in bondage.[36] New Jersey voters initially refused to ratify the constitutional amendments banning slavery and granting rights to the United States' black population.

Industrialization accelerated in the northern part of the state following completion of the Morris Canal in 1831. The canal allowed for coal to be brought from eastern Pennsylvania's Lehigh Valley to northern New Jersey's growing industries in Paterson, Newark, and Jersey City.

In 1844, the second state constitution was ratified and brought into effect. Counties thereby became districts for the State Senate, and some realignment of boundaries (including the creation of Mercer County) immediately followed. This provision was retained in the 1947 Constitution, but was overturned by the Supreme Court of the United States in 1962 by the decision Baker v. Carr. While the Governorship was stronger than under the 1776 constitution, the constitution of 1844 created many offices that were not responsible to him, or to the people, and it gave him a three-year term, but he could not succeed himself.

New Jersey was one of the few Union states (the others being Delaware and Kentucky) to select a candidate other than Abraham Lincoln twice in national elections, and sided with Stephen Douglas (1860) and George B. McClellan (1864) during their campaigns. McClellan, a native Philadelphian, had New Jersey ties and formally resided in New Jersey at the time; he later became Governor of New Jersey (1878–81). (In New Jersey, the factions of the Democratic party managed an effective coalition in 1860.) During the American Civil War, the state was led first by Republican Governor Charles Smith Olden, then by Democrat Joel Parker. During the course of the war, over 80,000 from the state enlisted in the Northern army; unlike many states, including some Northern ones, no battle was fought there.

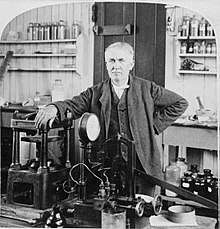

In the Industrial Revolution, cities like Paterson grew and prospered. Previously, the economy had been largely agrarian, which was problematically subject to crop failures and poor soil. This caused a shift to a more industrialized economy, one based on manufactured commodities such as textiles and silk. Inventor Thomas Edison also became an important figure of the Industrial Revolution, having been granted 1,093 patents, many of which for inventions he developed while working in New Jersey. Edison's facilities, first at Menlo Park and then in West Orange, are considered perhaps the first research centers in the U.S. Christie Street in Menlo Park was the first thoroughfare in the world to have electric lighting. Transportation was greatly improved as locomotion and steamboats were introduced to New Jersey.

Iron mining was also a leading industry during the middle to late 19th century. Bog iron pits in the southern New Jersey Pinelands were among the first sources of iron for the new nation.[37] Mines such as Mt. Hope, Mine Hill and the Rockaway Valley Mines created a thriving industry. Mining generated the impetus for new towns and was one of the driving forces behind the need for the Morris Canal. Zinc mines were also a major industry, especially the Sterling Hill Mine.

20th century

New Jersey prospered through the Roaring Twenties. The first Miss America Pageant was held in 1921 in Atlantic City, the Holland Tunnel connecting Jersey City to Manhattan opened in 1927, and the first drive-in movie was shown in 1933 in Camden. During the Great Depression of the 1930s, the state offered begging licenses to unemployed residents,[38] the zeppelin airship Hindenburg crashed in flames over Lakehurst, and the SS Morro Castle beached itself near Asbury Park after going up in flames while at sea.

Through both World Wars, New Jersey was a center for war production, especially in naval construction, notably at Federal Shipbuilding and Drydock Company. Battleships, cruisers, and destroyers were made in the state. New Jersey manufactured 6.8 percent of total United States military armaments produced during World War II, ranking fifth among the 48 states.[39] In addition, Fort Dix (1917) (originally called "Camp Dix"),[40] Camp Merritt (1917)[41] and Camp Kilmer (1941)[42] were all constructed to house and train American soldiers through both World Wars. New Jersey also became a principal location for defense in the Cold War. Fourteen Nike Missile stations were constructed, especially for the defense of New York City and Philadelphia. PT-109, a motor torpedo boat commanded by Lt. (j.g.) John F. Kennedy in World War II, was built at the Elco Boatworks in Bayonne. The aircraft carrier USS Enterprise (CV-6) was briefly docked at the Military Ocean Terminal in Bayonne in the 1950s before she was sent to Kearney to be scrapped.[43] In 1962, the world's first nuclear-powered cargo ship, the NS Savannah, was launched at Camden.

In 1951, the New Jersey Turnpike opened, permitting fast travel by car and truck between North Jersey (and metropolitan New York) and South Jersey (and metropolitan Philadelphia).

In the 1960s, race riots erupted in many of the industrial cities of North Jersey. The first race riots in New Jersey occurred in Jersey City on August 2, 1964. Several others ensued in 1967, in Newark and Plainfield. Other riots followed the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in April 1968, just as in the rest of the country. A riot occurred in Camden in 1971.

As a result of an order from the New Jersey Supreme Court to fund schools equitably, the New Jersey legislature passed an income tax bill in 1976. Prior to this bill, the state had no income tax.[44]

21st century

In the early part of the 2000s, two light rail systems were opened: the Hudson–Bergen Light Rail in Hudson County and the River Line between Camden and Trenton. The intent of these projects were to encourage transit-oriented development in North Jersey and South Jersey, respectively. The HBLR in particular was credited with a revitalization of Hudson County and Jersey City in particular.[45][46][47][48] Urban revitalization has continued in North Jersey in the 21st century. As of 2014, Jersey City's Census-estimated population was 262,146,[49] with the largest population increase of any municipality in New Jersey since 2010,[50] representing an increase of 5.9% from the 2010 United States Census, when the city's population was enumerated at 247,597.[51][52] In 2010, Newark experienced its first population increase since the 1950s.

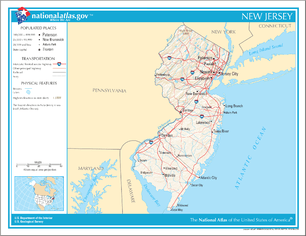

Geography

New Jersey is bordered on the north and northeast by New York (parts of which are across the Hudson River, Upper New York Bay, the Kill Van Kull, Newark Bay, and the Arthur Kill); on the east by the Atlantic Ocean; on the southwest by Delaware across Delaware Bay; and on the west by Pennsylvania across the Delaware River.

New Jersey is often broadly divided into three geographic regions: North Jersey, Central Jersey, and South Jersey. Some New Jersey residents do not consider Central Jersey a region in its own right, but others believe it is a separate geographic and cultural area from the North and South.

Within those regions are five distinct areas, based upon natural geography and population concentration. Northeastern New Jersey lies closest to Manhattan in New York City, and up to 1 million residents commute daily into the city for work, often via public transportation.[55] Northwestern New Jersey, is more wooded, rural, and mountainous. The Jersey Shore, along the Atlantic Coast in Central and South Jersey, has its own unique natural, residential, and cultural characteristics owing to its location by the ocean. The Delaware Valley includes the southwestern counties of the state, which reside within the Philadelphia Metropolitan Area. The Pine Barrens region is in the southern interior of New Jersey. Covered rather extensively by mixed pine and oak forest, it has a much lower population density than much of the rest of the state.

The federal Office of Management and Budget divides New Jersey's counties into seven Metropolitan Statistical Areas, with 16 counties included in either the New York City or Philadelphia metro areas. Four counties have independent metro areas, and Warren County is part of the Pennsylvania-based Lehigh Valley metro area. New Jersey is also at the center of the Northeast megalopolis.

High Point, in Montague Township, Sussex County, is the state's highest elevation, at 1,803 feet (550 m). The Palisades are a line of steep cliffs on the west side of the Hudson River, in Bergen and Hudson Counties. Major New Jersey rivers include the Hudson, Delaware, Raritan, Passaic, Hackensack, Rahway, Musconetcong, Mullica, Rancocas, Manasquan, Maurice, and Toms rivers.

National parks, monuments, and historic landmarks

- Appalachian National Scenic Trail

- Delaware National Scenic River

- Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area

- Ellis Island National Monument

- Gateway National Recreation Area in Monmouth County

- Great Egg Harbor River

- Morristown National Historical Park in Morristown

- New Jersey Coastal Heritage Trail Route

- New Jersey Pinelands National Reserve

- Paterson Great Falls National Historical Park

- Thomas Edison National Historical Park in West Orange

Prominent geographic features

Climate

There are two climatic conditions in the state. The south, central, and northeast parts of the state have a humid subtropical climate, while the northwest has a humid continental climate (microthermal), with much cooler temperatures due to higher elevation. New Jersey receives between 2,400 and 2,800 hours of sunshine annually.[56]

Summers are typically hot and humid, with statewide average high temperatures of 82–87 °F (28–31 °C) and lows of 60–69 °F (16–21 °C); however, temperatures exceed 90 °F (32 °C) on average 25 days each summer, exceeding 100 °F (38 °C) in some years. Winters are usually cold, with average high temperatures of 34–43 °F (1–6 °C) and lows of 16 to 28 °F (−9 to −2 °C) for most of the state, but temperatures could, for brief periods, fall below 10 °F (−12 °C) and occasionally rise above 50 °F (10 °C). Northwestern parts of the state have significantly colder winters with sub-0 °F (−18 °C) being an almost annual occurrence. Spring and autumn may feature wide temperature variations, with lower humidity than summer. The USDA Plant Hardiness Zone classification ranges from 6 in the northwest of the state, to 7B near Cape May.[57] All-time temperature extremes recorded in New Jersey include 110 °F (43 °C) on July 10, 1936 in Runyon, Middlesex County and −34 °F (−37 °C) on January 5, 1904 in River Vale, Bergen County.[58]

Average annual precipitation ranges from 43 to 51 inches (1,100 to 1,300 mm), uniformly spread through the year. Average snowfall per winter season ranges from 10–15 inches (25–38 cm) in the south and near the seacoast, 15–30 inches (38–76 cm) in the northeast and central part of the state, to about 40–50 inches (1.0–1.3 m) in the northwestern highlands, but this often varies considerably from year to year. Precipitation falls on an average of 120 days a year, with 25 to 30 thunderstorms, most of which occur during the summer.

During winter and early spring, New Jersey can experience "nor'easters," which are capable of causing blizzards or flooding throughout the northeastern United States. Hurricanes and tropical storms (such as Tropical Storm Floyd in 1999[59]), tornadoes, and earthquakes are rare, although New Jersey was severely impacted by Hurricane Sandy on October 29, 2012 with the storm making landfall in the state at 90 mph.

| Average high and low temperatures in various cities of New Jersey °C (°F)[1][2][3] | |||||||||||||

| City | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | |

| Sussex | 1/−9 (34/16) | 3/−8 (38/18) | 8/−4 (47/26) | 15/2 (59/36) | 21/7 (70/45) | 25/12 (78/55) | 28/16 (82/60) | 27/14 (81/58) | 23/10 (73/50) | 17/4 (62/38) | 11/−1 (51/31) | 4/−6 (39/22) | |

| Newark | 4/−4 (39/24) | 6/−3 (42/27) | 10/1 (51/34) | 17/7 (62/44) | 22/12 (72/53) | 28/17 (82/63) | 30/20 (86/69) | 29/20 (84/68) | 25/15 (77/60) | 18/9 (65/48) | 13/4 (55/39) | 6/−1 (44/30) | |

| Kinnelone | 0/−8 (35/15) | 2/−8 (37/18) | 7/-4 (46/26) | 16/2 (60/36) | 21/7 (69/45) | 24/12 (76/66) | 28/16 (83/60) | 27/14 (81/58) | 23/10 (73/50) | 16/4 (60/38) | 11/-2 (51/29) | 4/−6 (39/22) | |

| Atlantic City | 5/−2 (42/29) | 6/−1 (44/31) | 10/3 (50/37) | 14/8 (58/46) | 19/13 (67/55) | 24/18 (76/64) | 27/21 (81/70) | 27/21 (80/70) | 24/18 (75/64) | 18/11 (65/53) | 13/6 (56/43) | 8/1 (46/34) | |

| Cape May | 6/−2 (42/28) | 7/−2 (44/29) | 11/2 (51/35) | 16/7 (61/44) | 21/12 (70/53) | 26/17 (79/63) | 29/20 (85/68) | 29/19 (83/67) | 25/16 (78/61) | 19/9 (67/50) | 14/4 (57/41) | 8/0 (47/32) | |

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1790 | 184,139 | — | |

| 1800 | 211,149 | 14.7% | |

| 1810 | 245,562 | 16.3% | |

| 1820 | 277,575 | 13.0% | |

| 1830 | 320,823 | 15.6% | |

| 1840 | 373,306 | 16.4% | |

| 1850 | 489,555 | 31.1% | |

| 1860 | 672,035 | 37.3% | |

| 1870 | 906,096 | 34.8% | |

| 1880 | 1,131,116 | 24.8% | |

| 1890 | 1,444,933 | 27.7% | |

| 1900 | 1,883,669 | 30.4% | |

| 1910 | 2,537,167 | 34.7% | |

| 1920 | 3,155,900 | 24.4% | |

| 1930 | 4,041,334 | 28.1% | |

| 1940 | 4,160,165 | 2.9% | |

| 1950 | 4,835,329 | 16.2% | |

| 1960 | 6,066,782 | 25.5% | |

| 1970 | 7,168,164 | 18.2% | |

| 1980 | 7,364,823 | 2.7% | |

| 1990 | 7,730,188 | 5.0% | |

| 2000 | 8,414,350 | 8.9% | |

| 2010 | 8,791,894 | 4.5% | |

| Est. 2017 | 9,005,644 | 2.4% | |

| Source: 2017 Estimate[61] | |||

State population

The United States Census Bureau estimates that the population of New Jersey was 8,958,013 on July 1, 2015, a 1.89% increase since the 2010 United States Census.[62] Residents of New Jersey are most commonly referred to as "New Jerseyans" or, less commonly, as "New Jerseyites". As of the 2010 census, there were 8,791,894 people residing in the state. The racial makeup of the state was:

- 68.6% White American

- 13.7% African American

- 8.3% Asian American

- 0.3% Native American

- 2.7% Multiracial American

- 6.4% other races

17.7% of the population were Hispanic or Latino (of any race).

| Racial composition | 1970[63] | 1990[63] | 2000[64] | 2010[65] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 88.6% | 79.3% | 72.5% | 68.6% |

| Black | 10.7% | 13.4% | 13.6% | 13.7% |

| Asian | 0.3% | 3.5% | 5.7% | 8.3% |

| Native | 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.3% |

| Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander | – | – | – | – |

| Other race | 0.3% | 3.6% | 5.4% | 6.4% |

| Two or more races | – | – | 2.5% | 2.7% |

Non-Hispanic Whites were 58.9% of the population in 2011,[66] down from 85% in 1970.[67]

In 2010, unauthorized immigrants constituted an estimated 6.2% of the population. This was the fourth-highest percentage of any state in the country.[68] There were an estimated 550,000 illegal immigrants in the state in 2010.[69]

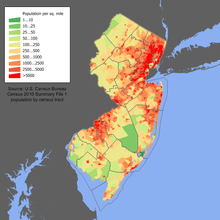

The United States Census Bureau, as of July 1, 2017, estimated New Jersey's population at 9,005,644,[61] which represents an increase of 213,750, or 2.4%, since the last census in 2010. As of 2010, New Jersey was the eleventh-most populous state in the United States, and the most densely populated, at 1,185 residents per square mile (458 per km2), with most of the population residing in the counties surrounding New York City, Philadelphia, and along the eastern Jersey Shore, while the extreme southern and northwestern counties are relatively less dense overall. It is also the second wealthiest state according to the U.S. Census Bureau.[21]

The center of population for New Jersey is located in Middlesex County, in the town of Milltown, just east of the New Jersey Turnpike.[70]

New Jersey is home to more scientists and engineers per square mile than anywhere else in the world.[71][72][73]

On October 21, 2013, same-sex marriages commenced in New Jersey.[74]

.svg.png)

New Jersey is one of the most ethnically and religiously diverse states in the country. As of 2011, 56.4% of New Jersey's children under the age of one belonged to racial or ethnic minority groups, meaning that they had at least one parent who was not non-Hispanic white.[75] It has the second largest Jewish population by percentage (after New York);[76] the second largest Muslim population by percentage (after Michigan); the largest population of Peruvian Americans in the United States; the largest population of Cubans outside of Florida; the third highest Asian population by percentage; and the third highest Italian population by percentage, according to the 2000 Census. African Americans, Hispanics (Puerto Ricans and Dominicans), West Indians, Arabs, and Brazilian and Portuguese Americans are also high in number. New Jersey has the third highest Asian Indian population of any state by absolute numbers and the highest by percentage,[77][78][79][80] with Bergen County home to America's largest Malayali community.[81] Overall, New Jersey has the third largest Korean population, with Bergen County home to the highest Korean concentration per capita of any U.S. county[82] (6.9% in 2011). New Jersey also has the fourth largest Filipino population, and fourth largest Chinese population, per the 2010 U.S. Census. The five largest ethnic groups in 2000 were: Italian (17.9%), Irish (15.9%), African (13.6%), German (12.6%), Polish (6.9%).

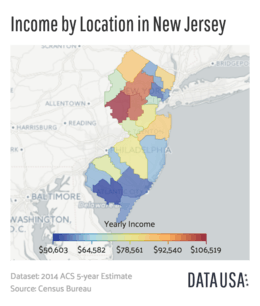

Newark was the fourth poorest of U.S. cities with over 250,000 residents in 2008,[83] but New Jersey as a whole had the second-highest median household income as of 2014.[21] This is largely because so much of New Jersey consists of suburbs, most of them affluent, of New York City and Philadelphia. New Jersey is also the most densely populated state, and the only state that has had every one of its counties deemed "urban" as defined by the Census Bureau's Combined Statistical Area.[84]

In 2010, 6.2% of its population was reported as under age 5, 23.5% under 18, and 13.5% were 65 or older; and females made up approximately 51.3% of the population.[90]

A study by the Pew Research Center found that in 2013, New Jersey was the only U.S. state in which immigrants born in India constituted the largest foreign-born nationality, representing roughly 10% of all foreign-born residents in the state.[89]

For further information on various ethnic groups and neighborhoods prominently featured within New Jersey, see the following articles:

- Indians in the New York City metropolitan region

- Chinese in the New York City metropolitan region

- List of U.S. cities with significant Korean American populations

- Filipinos in the New York City metropolitan region

- Filipinos in New Jersey

- Russians in the New York City metropolitan region

- Bergen County

- Jersey City

- India Square in Jersey City, home to the highest concentration of Asian Indians in the Western Hemisphere

- Ironbound, a Portuguese and Brazilian enclave in Newark

- Five Corners, a Filipino enclave in Jersey City

- Havana on the Hudson, a Cuban enclave in Hudson County

- Koreatown, Fort Lee, a Korean enclave in southeast Bergen County

- Koreatown, Palisades Park, also a Korean enclave in southeast Bergen County

- Little Bangladesh, a Bangladeshi enclave in Paterson

- Little Istanbul, also known as Little Ramallah, a Middle Eastern enclave in Paterson

- Little Lima, a Peruvian enclave in Paterson

Birth data

As of 2011, 56.4% of New Jersey's population younger than age 1 were minorities (meaning that they had at least one parent who was not non-Hispanic white).[91]

Note: Births in table don't add up, because Hispanics are counted both by their ethnicity and by their race, giving a higher overall number.

| Race | 2013[92] | 2014[93] | 2015[94] | 2016[95] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White: | 71,729 (69.9%) | 71,033 (68.8%) | 72,400 (70.2%) | ... |

| > Non-Hispanic White | 48,018 (46.8%) | 48,196 (46.6%) | 47,425 (46.0%) | 46,076 (44.9%) |

| Black | 19,139 (18.7%) | 20,102 (19.4%) | 18,363 (17.8%) | 13,870 (13.5%) |

| Asian | 11,511 (11.2%) | 11,977 (11.6%) | 12,192 (11.8%) | 12,053 (11.7%) |

| American Indian | 196 (0.2%) | 193 (0.2%) | 172 (0.2%) | 62 (0.0%) |

| Hispanic (of any race) | 27,251 (26.6%) | 27,267 (26.4%) | 27,919 (27.1%) | 28,083 (27.3%) |

| Total New Jersey | 102,575 (100%) | 103,305 (100%) | 103,127 (100%) | 102,647 (100%) |

- Since 2016, data for births of White Hispanic origin are not collected, but included in one Hispanic group; persons of Hispanic origin may be of any race.

Languages

| Language | Percentage of population (as of 2010)[96] |

|---|---|

| Spanish | 14.59% |

| Chinese (including Cantonese and Mandarin) | 1.23% |

| Italian | 1.06% |

| Portuguese | 1.06% |

| Filipino | 0.96% |

| Korean | 0.89% |

| Gujarati | 0.83% |

| Polish | 0.79% |

| Hindi | 0.71% |

| Arabic | 0.62% |

| Russian | 0.56% |

As of 2010, 71.31% (5,830,812) of New Jersey residents age 5 and older spoke English at home as a primary language, while 14.59% (1,193,261) spoke Spanish, 1.23% (100,217) Chinese (which includes Cantonese and Mandarin), 1.06% (86,849) Italian, 1.06% (86,486) Portuguese, 0.96% (78,627) Tagalog, and Korean was spoken as a main language by 0.89% (73,057) of the population over the age of five. In total, 28.69% (2,345,644) of New Jersey's population age 5 and older spoke a mother language other than English.[96]

A diverse collection of languages has since evolved amongst the state's population, given that New Jersey has become cosmopolitan and is home to ethnic enclaves of non-English-speaking communities:[97][98][99][100]

- Albanian – Paterson, Garfield

- Arabic – Paterson, Jersey City

- Armenian – Bergen County

- Bahasa Indonesia – Gloucester City, Middlesex, Somerset, and Union counties

- Bengali – Paterson

- Cantonese

- Farsi

- Greek

- Gujarati

- Hebrew

- Hindi – Jersey City, Edison, Iselin, Mount Laurel, Cherry Hill, Princeton, Robbinsville

- Italian- widespread across the state especially in Camden County, Essex, and Bergen counties.

- Japanese – Edgewater and Fort Lee boroughs in Bergen County

- Kannada

- Korean – Bergen County (numerous municipalities); Cherry Hill

- Macedonian – Bergen County

- Malayalam – Bergen County

- Mandarin Chinese

- Marathi

- Polish – Bergen County (Garfield, Wallington); Mercer County (Top Road, Lawrence Township, Hopewell); Linden

- Portuguese – Ironbound section of Newark; Elizabeth

- Punjabi

- Russian – Fair Lawn borough of Bergen County, Princeton area and Mercer County

- Spanish- widespread across the state.

- Tagalog

- Tamil

- Telugu

- Turkish – Little Istanbul section of Paterson, Mount Ephraim (which has a large, vibrant and growing Turkish Community), Delran, Cherry Hill

- Ukrainian

- Urdu - Mount Ephraim has a significant amount of residents of Pakistani origin.

- Vietnamese – Atlantic City, Camden/Cherry Hill, Edison Township, Jersey City

- Yiddish – Lakewood Township, Ocean County

Federal Courthouse in Camden, which is connected to Philadelphia via the Benjamin Franklin Bridge in the background

Federal Courthouse in Camden, which is connected to Philadelphia via the Benjamin Franklin Bridge in the background

Religion

By number of adherents, the largest denominations in New Jersey, according to the Association of Religion Data Archives in 2010, were the Roman Catholic Church with 3,235,290; Islam with 160,666; and the United Methodist Church with 138,052.[108] The world's largest Hindu temple was inaugurated in Robbinsville, Mercer County, in central New Jersey during 2014, a BAPS temple.[109]

Cathedral Basilica of the Sacred Heart in Newark, the fifth-largest cathedral in North America, is the seat of the city's Roman Catholic Archdiocese.

Cathedral Basilica of the Sacred Heart in Newark, the fifth-largest cathedral in North America, is the seat of the city's Roman Catholic Archdiocese.- Temple Sharey Tefilo-Israel, in South Orange, Essex County. New Jersey is home to the second-highest Jewish American (Hebrew) population per capita, after New York.

Swaminarayan Akshardham (Devnagari) in Robbinsville, Mercer County, inaugurated in 2014 as the world's largest Hindu temple.[110]

Swaminarayan Akshardham (Devnagari) in Robbinsville, Mercer County, inaugurated in 2014 as the world's largest Hindu temple.[110]

Settlements

- Bergen County: 905,116[66]

- Middlesex County: 809,858

- Essex County: 783,969

- Hudson County: 634,266

- Monmouth County: 630,380

- Ocean County: 576,567

- Union County: 536,499

- Camden County: 513,657

- Passaic County: 501,226

- Morris County: 492,276

For its overall population and nation-leading population density, New Jersey has a relative paucity of classic large cities. This paradox is most pronounced in Bergen County, New Jersey's most populous county, whose more than 930,000 residents in 2014 inhabited 70 municipalities, the most populous being Hackensack, with 44,519 residents estimated in 2014. Many urban areas extend far beyond the limits of a single large city, as New Jersey cities (and indeed municipalities in general) tend to be geographically small; three of the four largest cities in New Jersey by population have under 20 square miles of land area, and eight of the top ten, including all of the top five have land area under 30 square miles. As of the United States 2010 Census, only four municipalities had populations in excess of 100,000, although Edison and Woodbridge came very close.

| Rank | Name | County | Pop. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Newark  Jersey City |

1 | Newark | Essex | 281,764 | Paterson Elizabeth | ||||

| 2 | Jersey City | Hudson | 264,152 | ||||||

| 3 | Paterson | Passaic | 147,100 | ||||||

| 4 | Elizabeth | Union | 128,640 | ||||||

| 5 | Edison | Middlesex | 101,996 | ||||||

| 6 | Woodbridge Township | Middlesex | 101,389 | ||||||

| 7 | Lakewood Township | Ocean | 100,758 | ||||||

| 8 | Toms River | Ocean | 91,837 | ||||||

| 9 | Hamilton Township (Mercer) | Mercer | 88,400 | ||||||

| 10 | Trenton | Mercer | 84,056 | ||||||

Wealth

Economy

.svg.png)

The U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis estimates that New Jersey's gross state product in 2016 was $575 billion.[113] New Jersey's estimated taxpayer burden in 2015 was $59,400 per taxpayer.[114]

Affluence

New Jersey's per capita gross state product in 2008 was $54,699, second in the U.S. and above the national per capita gross domestic product of $46,588.[115] Its per capita income was the third highest in the nation with $51,358.[115] In 2013, the state had the second-largest number of millionaires per capita in the United States (ratio of 7.49%), according to a study by Phoenix Marketing International.[116] It is ranked second in the nation by the number of places with per capita incomes above national average with 76.4%. Nine of New Jersey's counties are in the wealthiest 100 of the country.

Fiscal policy

New Jersey has seven tax brackets that determine state income tax rates, which range from 1.4% (for income below $20,000) to 8.97% (for income above $500,000).[117]

The standard sales tax rate as of January 1, 2018, is 6.625%, applicable to all retail sales unless specifically exempt by law. This rate, which is comparably lower than that of New York City, often attracts numerous shoppers from New York City, often to suburban Paramus, New Jersey, which has five malls, one of which (the Garden State Plaza) has over two million square feet of retail space. Tax exemptions include most food items for at-home preparation, medications, most clothing, footwear and disposable paper products for use in the home.[118] There are 27 Urban Enterprise Zone statewide, including sections of Paterson, Elizabeth, and Jersey City. In addition to other benefits to encourage employment within the zone, shoppers can take advantage of a reduced 3.3125% sales tax rate (half the rate rate charged statewide) at eligible merchants.[119][120][121]

New Jersey has the highest cumulative tax rate of all 50 states with residents paying a total of $68 billion in state and local taxes annually with a per capita burden of $7,816 at a rate of 12.9% of income.[122] All real property located in the state is subject to property tax unless specifically exempted by statute. New Jersey does not assess an intangible personal property tax, but it does impose an inheritance tax.

Federal taxation disparity

New Jersey consistently ranks as having one of the highest proportional levels of disparity of any state in the United States, based upon what it receives from the federal government relative to what it gives. In 2015, WalletHub ranked New Jersey the state least dependent upon federal government aid overall and having the fourth lowest return on taxpayer investment from the federal government, at 48 cents per dollar.[123]

New Jersey has one of the highest tax burdens in the nation.[124] Factors for this include the large federal tax liability which is not adjusted for New Jersey's higher cost of living and Medicaid funding formulas. As shown by the study, incomes tend to be higher in New Jersey, which puts those in higher tax brackets especially vulnerable to the alternative minimum tax.

Industries

New Jersey's economy is multifaceted, but is centered on the pharmaceutical industry, the financial industry, chemical development, telecommunications, food processing, electric equipment, printing, publishing, and tourism. New Jersey's agricultural outputs are nursery stock, horses, vegetables, fruits and nuts, seafood, and dairy products.[125] New Jersey ranks second among states in blueberry production, third in cranberries and spinach, and fourth in bell peppers, peaches, and head lettuce.[126] The state harvests the fourth-largest number of acres planted with asparagus.[127]

Although New Jersey is home to many energy-intensive industries, its energy consumption is only 2.7% of the U.S. total, and its carbon dioxide emissions are 0.8% of the U.S. total. Its comparatively low greenhouse gas emissions can be attributed to the state's use of nuclear power. According to the Energy Information Administration, nuclear power dominates New Jersey's electricity market, typically supplying more than one-half of state generation. New Jersey has three nuclear power plants, including the Oyster Creek Nuclear Generating Station, which came online in 1969 and is the oldest operating nuclear plant in the country.[128]

New Jersey has a strong scientific economy and is home to major pharmaceutical and telecommunications firms, drawing on the state's large and well-educated labor pool. There is also a strong service economy in retail sales, education, and real estate, serving residents who work in New York City or Philadelphia.

Shipping is a key industry in New Jersey because of the state's strategic geographic location, the Port of New York and New Jersey being the busiest port on the East Coast. The Port Newark-Elizabeth Marine Terminal was the world's first container port and today is one of the world's largest.

New Jersey hosts several business headquarters, including twenty-four Fortune 500 companies.[129] Paramus in Bergen County has become the top retail zip code (07652) in the United States, with the municipality generating over $5 billion annually in retail sales.[130][131] Several New Jersey counties, such as Somerset (7), Morris (10), Hunterdon (13), Bergen (21), Monmouth (42) are ranked among the highest-income counties in the United States.

Tourism

New Jersey's location at the center of the Northeast megalopolis and its extensive transportation system have put over one-third of all United States residents and many Canadian residents within overnight distance by land. This accessibility to consumer revenue has enabled seaside resorts such as Atlantic City and the remainder of the Jersey Shore, as well as the state's other natural and cultural attractions, to contribute significantly to New Jersey's tourism revenue of $43.4 billion and 95 million tourist visits in 2015, directly supporting 318,330 jobs and sustaining more than 512,000 jobs including peripheral impacts.[132]

Gambling

In 1976, a referendum of New Jersey voters approved casino gambling in Atlantic City, where the first legalized casino opened in 1978.[133] At that time, Las Vegas was the only other casino resort in the country.[134] Today, several casinos lie along the Atlantic City Boardwalk,[135] the first and longest boardwalk in the world.[136] Atlantic City experienced a dramatic contraction in its stature as a gambling destination after 2010, including the closure of multiple casinos since 2014, spurred by competition from the advent of legalized gambling in other northeastern U.S. states.[137][138] On February 26, 2013, Governor Chris Christie signed online gambling into law.[139]

Natural resources

Forests cover 45%, or approximately 2.1 million acres, of New Jersey's land area.[140] The chief tree of the northern forests is the oak. The Pine Barrens, consisting of pine forests, is in the southern part of the state.

Some mining activity of zinc, iron, and manganese still takes place in the area in and around the Franklin Furnace.

New Jersey is second in the nation in solar power installations,[141] enabled by one of the country's most favorable net metering policies, and the renewable energy certificates program. The state has more than 10,000 solar installations.[142]

Education

.jpg)

In 2010, there were 605 school districts in the state.[144]

Secretary of Education Rick Rosenberg, appointed by Governor Jon Corzine, created the Education Advancement Initiative (EAI) to increase college admission rates by 10% for New Jersey's high school students, decrease dropout rates by 15%, and increase the amount of money devoted to schools by 10%. Rosenberg retracted this plan when criticized for taking the money out of healthcare to fund this initiative.

In 2010, the state government paid all of the teachers' premiums for health insurance,[144] but currently all NJ public teachers pay a portion of their own health insurance premiums.

In 2015, New Jersey spent more per each public school student than any other U.S. state except New York, Alaska, and Connecticut, amounting to $18,235 spent per pupil. Over 50% of the expenditure was allocated to student instruction.[145]

According to 2011 Newsweek statistics, students of High Technology High School in Lincroft, Monmouth County and Bergen County Academies in Hackensack, Bergen County registered average SAT scores of 2145 and 2100, respectively,[146] representing the second- and third-highest scores, respectively, of all listed U.S. high schools.[146]

Princeton University in Princeton, Mercer County, one of the world's mot prominent research universities, is often featured at or near the top of various national and global university rankings, topping the 2019 list of U.S. News & World Report.[147] In 2013, Rutgers University, headquartered in New Brunswick, Middlesex County as the flagship institution of higher education in New Jersey, gained medical and dental schools, augmenting its profile as a national research university as well.[148]

In 2014, New Jersey's school systems were ranked at the top of all fifty U.S. states by financial website Wallethub.com.[149] In 2018, New Jersey's overall educational system was ranked second among all states to Massachusetts by U.S. News & World Report.[150]

Nine New Jersey high schools were ranked among the top 25 in the U.S. on the Newsweek "America's Top High Schools 2016" list, more than from any other state.[151] A 2017 UCLA Civil Rights project found that New Jersey has the sixth-most segregated classrooms in the United States.[152]

Culture

General

New Jersey has continued to play a prominent role as a U.S. cultural nexus. Like every state, New Jersey has its own cuisine, religious communities, museums, and halls of fame.

New Jersey is the birthplace of modern inventions such as: FM radio, the motion picture camera, the lithium battery, the light bulb, transistors, and the electric train. Other New Jersey creations include: the drive-in movie, the cultivated blueberry, cranberry sauce, the postcard, the boardwalk, the zipper, the phonograph, saltwater taffy, the dirigible, the seedless watermelon,[153] the first use of a submarine in warfare, and the ice cream cone.[154]

Diners are iconic to New Jersey. The state is home to many diner manufacturers and has over 600 diners, more than any other place in the world.[155]

New Jersey is the only state without a state song. I'm From New Jersey is incorrectly listed on many websites as being the New Jersey state song, but it was not even a contender when in 1996 the New Jersey Arts Council submitted their suggestions to the New Jersey Legislature.[156]

New Jersey is frequently the target of jokes in American culture,[157] especially from New York City-based television shows, such as Saturday Night Live. Academic Michael Aaron Rockland attributes this to New Yorkers' view that New Jersey is the beginning of Middle America. The New Jersey Turnpike, which runs between two major East Coast cities, New York City and Philadelphia, is also cited as a reason, as people who traverse through the state may only see its industrial zones.[158] Reality television shows like Jersey Shore and The Real Housewives of New Jersey have reinforced stereotypical views of New Jersey culture,[159] but Rockland cited The Sopranos and the music of Bruce Springsteen as exporting a more positive image.[158]

Cuisine

New Jersey is known for several foods developed within the region, including pork roll (or Taylor ham), cheesesteaks, and scrapple.

Credit for the development of submarine sandwiches is claimed by several states with substantial Italian American populations, including New Jersey.[160]

Music

New Jersey has long been an important origin for both rock and rap music. Prominent musicians from or with significant connections to New Jersey include:

- Singer Frank Sinatra was born in Hoboken. He sang with a neighborhood vocal group, the Hoboken Four, and appeared in neighborhood theater amateur shows before he became an Academy Award–winning actor.

- Bruce Springsteen, who has sung of New Jersey life on most of his albums, is from Freehold. Some of his songs that represent New Jersey life are "Born to Run", "Spirit In The Night," "Rosalita (Come Out Tonight)", "Thunder Road", "Atlantic City", and "Jungleland".

- The Jonas Brothers all reside in Wyckoff, New Jersey, where the eldest and youngest brothers of the group, Kevin and Frankie Jonas, were born.

- Irvington's Queen Latifah was the first female rapper to succeed in music, film, and television.

- Lauryn Hill is from South Orange, New Jersey. Her 1998 debut solo album, The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill, sold 10 million copies internationally.[161] She also sold millions with The Fugees second album The Score.

- Southside Johnny, eponymous leader of Southside Johnny and the Asbury Jukes was raised in Ocean Grove. He is considered the "Grandfather of the New Jersey Sound" and is cited by Jersey-born Jon Bon Jovi as his reason for singing.

- Redman (Reggie Noble) was born, raised, and resides in Newark.

- All members of The Sugarhill Gang were born in Englewood.[162]

- Roc-A-Fella Records rap producer Just Blaze is from Paterson, New Jersey.[163]

- Jon Bon Jovi, from Sayreville, reached fame in the 1980s with hard rock outfit Bon Jovi. The band has also written many songs about life in New Jersey including "Livin' On A Prayer" and named one of their albums after the state. (see New Jersey)

- Singer Dionne Warwick was born in East Orange.[164]

- Singer Whitney Houston (who is Dionne Warwick's cousin) was born in Newark, and grew up in neighboring East Orange.[163]

- Jazz pianist and bandleader Count Basie was born in Red Bank in 1904.[165] In the 1960s, he collaborated on several albums with fellow New Jersey native Frank Sinatra. The Count Basie Theatre in Red Bank is named in his honor.

- Parliament-Funkadelic, the funk music collective, was formed in Plainfield by George Clinton.

- Asbury Park is home of The Stone Pony, which Bruce Springsteen and Bon Jovi frequented early in their careers[166]

- Hip-hop pioneers Naughty By Nature are from East Orange.[167]

- In 1964, the Isley Brothers founded the record label T-Neck Records, named after Teaneck, their home at the time.[168]

- The Broadway musical "Jersey Boys" is based on the lives of the members of the Four Seasons, three of whose members were born in New Jersey (Tommy DeVito, Frankie Valli, and Nick Massi) while a fourth Bob Gaudio was born out of state but raised in Bergenfield, NJ.

- Jazz pianist Bill Evans was born in Plainfield in 1929.[169]

- Post-hardcore band Thursday was formed in New Brunswick, New Jersey.[170] Numerous songs reference the city.

- Horror punk band The Misfits hail from Lodi, as well as their founder Glenn Danzig.[171]

- Punk rock poet Patti Smith is from Mantua.[172]

- Indie rock veterans Yo La Tengo are based in Hoboken. They also have a song called "The Night Falls on Hoboken".

- New Jersey was the East Coast hub for ska music in the 1990s. Some of the most popular ska bands, such as Catch 22 and Streetlight Manifesto, come from East Brunswick.

- Black Label Society's and Ozzy Osbourne's famed guitarist Zakk Wylde was born in Bayonne and raised in Jackson

- The Bouncing Souls original four members grew up in Basking Ridge and formed in New Brunswick in the late 1980s.

- As a child, singer Akon grew up in Union City, New Jersey, Newark, New Jersey, and Jersey City, New Jersey.

- My Chemical Romance's Frank Iero, Gerard Way, Mikey Way, and Ray Toro all are from New Jersey.

- Cobra Starship frontman Gabe Saporta is from New Jersey

- Punk band The Gaslight Anthem hails from New Brunswick, New Jersey.[173]

- Experimental metal band The Dillinger Escape Plan are from Morris Plains, NJ.

- Debbie Harry, born in Miami, Florida, in 1945 but raised by her adoptive parents in Hawthorne.

In comics and video games

- The fictional Gotham City, home to Batman, is depicted in DC Comics and the DC Extended Universe as being located in New Jersey.[174][175][176][177][178][179][180][181]

- The Lost and Damned (2009), The Ballad of Gay Tony and Max Payne 3 (2012) take place in New Jersey.

- The Grand Theft Auto series has parodied the state multiple times, with "New Guernsey" and "Alderney City" appearing as locations in games in the series.

Media

Newspapers

Major New Jersey newspapers including the following:

- Asbury Park Press

- Burlington County Times

- Courier News

- Courier-Post

- Cranford Chronicle

- Daily Record (Morristown)[182]

- The Express-Times

- Gloucester County Times

- Herald News

- Home News Tribune

- Hunterdon County Democrat

- Independent Press

- Jersey Journal

- The New Jersey Herald[183]

- The News of Cumberland County

- The Press of Atlantic City

- The Record[184]

- The Record-Press and Suburban News

- The Reporter (Somerset)

- The Star-Ledger

- The Times (Trenton)

- Today's Sunbeam

- Trentonian (Mercer)

- The Warren Reporter

Radio stations

Television and film

Motion picture technology was developed by Thomas Edison, with much of his early work done at his West Orange laboratory. Edison's Black Maria was the first motion picture studio. America's first motion picture industry started in 1907 in Fort Lee and the first studio was constructed there in 1909.[185] DuMont Laboratories in Passaic developed early sets and made the first broadcast to the private home.

A number of television shows and films have been filmed in New Jersey. Since 1978, the state has maintained a Motion Picture and Television Commission to encourage filming in-state.[186] New Jersey has long offered tax credits to television producers. Governor Chris Christie suspended the credits in 2010, but the New Jersey State Legislature in 2011 approved the restoration and expansion of the tax credit program. Under bills passed by both the state Senate and Assembly, the program offers 20 percent tax credits (22% in urban enterprise zones) to television and film productions that shoot in the state and meet set standards for hiring and local spending.[187]

Transportation

Roadways

The New Jersey Turnpike is one of the most prominent and heavily trafficked roadways in the United States. This toll road carries Interstate 95 traffic between Delaware and New York, and up and down the East Coast in general. Commonly referred to as simply "the Turnpike," it is known for its numerous rest areas named after prominent New Jerseyans.

The Garden State Parkway, or simply "the Parkway," carries relatively more in-state traffic than interstate traffic and runs from New Jersey's northern border to its southernmost tip at Cape May. It is the main route that connects the New York metropolitan area to the Jersey Shore and is consistently one of the safest roads in the nation. With a total of 15 travel and 6 shoulder lanes, the Driscoll Bridge on the Parkway, spanning the Raritan River in Middlesex County, is the widest motor vehicle bridge in the world by number of lanes as well as one of the busiest.[190]

New Jersey is connected to New York City via various key bridges and tunnels. The double-decked George Washington Bridge carries the heaviest load of motor vehicle traffic of any bridge in the world, at 102 million vehicles per year, across fourteen lanes.[188][189] It connects Fort Lee, New Jersey to the Washington Heights neighborhood of Upper Manhattan, and carries Interstate 95 and U.S. Route 1/9 across the Hudson River. The Lincoln Tunnel connects to Midtown Manhattan carrying New Jersey Route 495, and the Holland Tunnel connects to Lower Manhattan carrying Interstate 78. New Jersey is also connected to Staten Island by three bridges — from north to south, the Bayonne Bridge, the Goethals Bridge, and the Outerbridge Crossing.

New Jersey has interstate compacts with all three of its neighboring states. The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, the Delaware River Port Authority (with Pennsylvania), and the Delaware River and Bay Authority (with Delaware) operate most of the major transportation routes in and out of the state. Bridge tolls are collected in one direction only – it is free to cross into New Jersey, but motorists must pay when exiting the state, with a few exceptions.

It is unlawful for a customer to serve themselves gasoline in New Jersey. It became the last remaining U.S. state where all gas stations are required to sell full-service gasoline to customers at all times in 2016, after Oregon's introduction of restricted self-service gasoline availability took effect.[191]

Airports

Newark Liberty International Airport is one of the busiest airports in the United States. Operated by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, it is one of the three main airports serving the New York City area. United Airlines is the airport's largest tenant, operating an entire terminal there, which it uses as one of its primary hubs. FedEx Express operates a large cargo terminal at Newark as well. The adjacent Newark Airport railroad station provides access to Amtrak and NJ Transit trains along the Northeast Corridor Line.

Two smaller commercial airports, Atlantic City International Airport and Trenton-Mercer Airport, also operate in other parts of the state. Teterboro Airport in Bergen County, and Millville Municipal Airport in Cumberland County, are general aviation airports popular with private and corporate aircraft due to their proximity to New York City and the Jersey Shore, respectively.

Rail and bus

NJ Transit operates extensive rail and bus service throughout the state. A state-run corporation, it began with the consolidation of several private bus companies in North Jersey in 1979. In the early 1980s, it acquired Conrail's commuter train operations that connected suburban towns to New York City. Today, NJ Transit has eleven commuter rail lines that run through different parts of the state. Most of the lines end at either New York's Penn Station or Hoboken's Hoboken Terminal. One line provides service between Atlantic City and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

NJ Transit also operates three light rail systems in the state. The Hudson-Bergen Light Rail connects Bayonne to North Bergen, through Hoboken and Jersey City. The Newark Light Rail is partially underground, and connects downtown Newark with other parts of the city. The River Line connects Trenton and Camden.

The PATH is a rapid transit system consisting of four lines operated by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. It links Hoboken, Jersey City, Harrison and Newark with New York City. The PATCO Speedline is a rapid transit system that links Camden County to Philadelphia. Both the PATCO and the PATH are two of only six rapid transit systems in the United States to operate 24 hours a day.

Amtrak operates numerous long-distance passenger trains in New Jersey, both to and from neighboring states and around the country. In addition to the Newark Airport connection, other major Amtrak railway stations include Trenton Transit Center, Metropark, and the historic Newark Penn Station.

The Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority, or SEPTA, has two commuter rail lines that operate into New Jersey. The Trenton Line terminates at the Trenton Transit Center, and the West Trenton Line terminates at the West Trenton Rail Station in Ewing.

AirTrain Newark is a monorail connecting the Amtrak/NJ Transit station on the Northeast Corridor to the airport's terminals and parking lots.

Some private bus carriers still remain in New Jersey. Most of these carriers operate with state funding to offset losses and state owned buses are provided to these carriers, of which Coach USA companies make up the bulk. Other carriers include private charter and tour bus operators that take gamblers from other parts of New Jersey, New York City, Philadelphia, and Delaware to the casino resorts of Atlantic City.

Ferries

New York Waterway has ferry terminals at Belford, Jersey City, Hoboken, Weehawken, and Edgewater, with service to different parts of Manhattan. Liberty Water Taxi in Jersey City has ferries from Paulus Hook and Liberty State Park to Battery Park City in Manhattan. Statue Cruises offers service from Liberty State Park to the Statue of Liberty National Monument, including Ellis Island. SeaStreak offers services from the Raritan Bayshore to Manhattan, Martha's Vineyard, and Nantucket.

On the Delaware Bay, the Delaware River and Bay Authority operates the Cape May–Lewes Ferry, carrying both passengers and vehicles from New Jersey to Deleware. The agency also operates the Forts Ferry Crossing for passengers across the Delaware River. The Delaware River Port Authority operates the RiverLink Ferry between the Camden waterfront and Penn's Landing in Philadelphia.

Government and politics

Executive

.jpg)

The position of Governor of New Jersey has been considered one of the most powerful in the nation. Until 2010, the governor was the only statewide elected executive official in the state and appointed numerous government officials. Formerly, an acting governor was even more powerful as he simultaneously served as President of the New Jersey State Senate, thus directing half of the legislative and all of the executive process. In 2002 and 2007, President of the State Senate Richard Codey held the position of acting governor for a short time, and from 2004 to 2006 Codey became a long-term acting governor due to Jim McGreevey's resignation. A 2005 amendment to the state Constitution prevents the Senate President from becoming acting governor in the event of a permanent gubernatorial vacancy without giving up her or his seat in the state Senate. Phil Murphy (D) is the Governor. The governor's mansion is Drumthwacket, located in Princeton.

Before 2010, New Jersey was one of the few states without a lieutenant governor. Republican Kim Guadagno was elected the first Lieutenant Governor of New Jersey and took office on January 19, 2010. She was elected on the Republican ticket with Governor-Elect Chris Christie in the November 2009 NJ gubernatorial election. The position was created as the result of a Constitutional amendment to the New Jersey State Constitution passed by the voters on November 8, 2005 and effective as of January 17, 2006.

Legislative

The current version of the New Jersey State Constitution was adopted in 1947. It provides for a bicameral New Jersey Legislature, consisting of an upper house Senate of 40 members and a lower house General Assembly of 80 members. Each of the 40 legislative districts elects one State Senator and two Assembly members. Assembly members are elected for a two-year term in all odd-numbered years; State Senators are elected in the years ending in 1, 3, and 7 and thus serve either four- or two-year terms.

New Jersey is one of only five states that elects its state officials in odd-numbered years. (The others are Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Virginia.) New Jersey holds elections for these offices every four years, in the year following each federal Presidential election year. Thus, the last year when New Jersey elected a Governor was 2017; the next gubernatorial election will occur in 2021, with future gubernatorial elections to take place in 2025, 2029, 2033, etc.

Judicial

The New Jersey Supreme Court[192] consists of a Chief Justice and six Associate Justices. All are appointed by the Governor with the advice and consent of a majority of the membership of the State Senate. Justices serve an initial seven-year term, after which they can be reappointed to serve until age 70.

Most of the day-to-day work in the New Jersey courts is carried out in the Municipal Court, where simple traffic tickets, minor criminal offenses, and small civil matters are heard.

More serious criminal and civil cases are handled by the Superior Court for each county. All Superior Court judges are appointed by the Governor with the advice and consent of a majority of the membership of the State Senate. Each judge serves an initial seven-year term, after which he or she can be reappointed to serve until age 70. New Jersey's judiciary is unusual in that it still has separate courts of law and equity, like its neighbor Delaware but unlike most other U.S. states. The New Jersey Superior Court is divided into Law and Chancery Divisions at the trial level; the Law Division hears both criminal cases and civil lawsuits where the plaintiff's primary remedy is damages, while the Chancery Division hears family cases, civil suits where the plaintiff's primary remedy is equitable relief, and probate trials.

The Superior Court also has an Appellate Division, which functions as the state's intermediate appellate court. Superior Court judges are assigned to the Appellate Division by the Chief Justice.

There is also a Tax Court, which is a court of limited jurisdiction. Tax Court judges hear appeals of tax decisions made by County Boards of Taxation. They also hear appeals on decisions made by the Director of the Division of Taxation on such matters as state income, sales and business taxes, and homestead rebates. Appeals from Tax Court decisions are heard in the Appellate Division of Superior Court. Tax Court judges are appointed by the Governor for initial terms of seven years, and upon reappointment are granted tenure until they reach the mandatory retirement age of 70. There are 12 Tax Court judgeships.

Counties

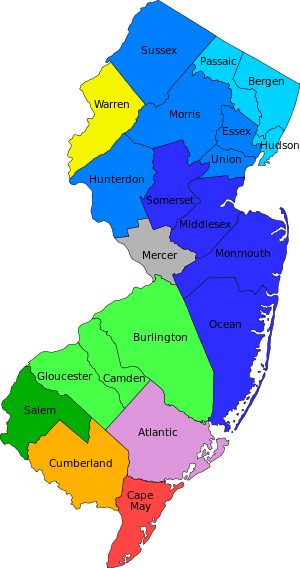

New Jersey is divided into 21 counties; 13 date from the colonial era. New Jersey was completely divided into counties by 1692; the present counties were created by dividing the existing ones; most recently Union County in 1857. New Jersey is the only state in the nation where elected county officials are called "Freeholders," governing each county as part of its own Board of Chosen Freeholders. The number of freeholders in each county is determined by referendum, and must consist of three, five, seven or nine members.

Depending on the county, the executive and legislative functions may be performed by the Board of Chosen Freeholders or split into separate branches of government. In 16 counties, members of the Board of Chosen Freeholders perform both legislative and executive functions on a commission basis, with each Freeholder assigned responsibility for a department or group of departments. In the other 5 counties (Atlantic, Bergen, Essex, Hudson and Mercer), there is a directly elected County Executive who performs the executive functions while the Board of Chosen Freeholders retains a legislative and oversight role. In counties without an Executive, a County Administrator (or County Manager) may be hired to perform day-to-day administration of county functions.

Municipalities

New Jersey currently has 565 municipalities; the number was 566 before Princeton Township and Princeton Borough merged to form the municipality of Princeton on January 1, 2013. Unlike other states, all New Jersey land is part of a municipality. In 2008, Governor Jon Corzine proposed cutting state aid to all towns under 10,000 people, to encourage mergers to reduce administrative costs.[193] In May 2009, the Local Unit Alignment Reorganization and Consolidation Commission began a study of about 40 small communities in South Jersey to decide which ones might be good candidates for consolidation.[194]

Forms of municipal government

| New Jersey municipal government |

||||

| Traditional forms | ||||

| Borough | Township | |||

|

||||

| Modern forms | ||||

| Walsh Act commission | ||||

| 1923 municipal manager | ||||

| Faulkner Act forms | ||||

| Mayor–council | Council–manager | |||

| Small municipality | ||||

| Mayor–council–administrator | ||||

| Nonstandard forms | ||||

| Special charter | ||||

| Changing form of municipal government | ||||

| Charter Study Commission | ||||

Starting in the 20th century, largely driven by reform-minded goals, a series of six modern forms of government was implemented. This began with the Walsh Act, enacted in 1911 by the New Jersey Legislature, which provided for a three- or five-member commission elected on a non-partisan basis. This was followed by the 1923 Municipal Manager Law, which offered a non-partisan council, provided for a weak mayor elected by and from the members of the council, and introduced a Council-manager government structure with an appointed manager responsible for day-to-day administration of municipal affairs.

The Faulkner Act, originally enacted in 1950 and substantially amended in 1981, offers four basic plans: Mayor-Council, Council-Manager, Small Municipality, and Mayor-Council-Administrator. The act provides many choices for communities with a preference for a strong executive and professional management of municipal affairs and offers great flexibility in allowing municipalities to select the characteristics of its government: the number of seats on the Council; seats selected at-large, by wards, or through a combination of both; staggered or concurrent terms of office; and a mayor chosen by the Council or elected directly by voters. Most large municipalities and a majority of New Jersey's residents are governed by municipalities with Faulkner Act charters. Municipalities can also formulate their own unique form of government and operate under a Special Charter with the approval of the New Jersey Legislature.

While municipalities retain their names derived from types of government, they may have changed to one of the modern forms of government, or further in the past to one of the other traditional forms, leading to municipalities with formal names quite baffling to the general public. For example, though there are four municipalities that are officially of the village type, Loch Arbour is the only one remaining with the village form of government. The other three villages – Ridgefield Park (now with a Walsh Act form), Ridgewood (now with a Faulkner Act Council-Manager charter) and South Orange (now operates under a Special Charter) – have all migrated to other non-village forms.

Politics

Social attitudes and issues

Socially, New Jersey is considered one of the more liberal states in the nation. Polls indicate that 60% of the population are self-described as pro-choice, although a majority are opposed to late trimester and intact dilation and extraction and public funding of abortion.[195][196] In a 2009 Quinnipiac University Polling Institute poll, a plurality supported same-sex marriage 49% to 43% opposed,[197] On October 18, 2013, the New Jersey Supreme Court rendered a provisional, unanimous (7–0 vote) order authorizing same-sex marriage in the state, pending a legal appeal by Governor Chris Christie,[198] who then withdrew this appeal hours after the inaugural same-sex marriages took place on October 21, 2013.[74]

New Jersey also has some of the most stringent gun control laws in the U.S. These include bans on assault firearms, hollow-nose bullets and even slingshots. No gun offense in New Jersey is graded less than a felony. BB guns and black-powder guns are all treated as modern firearms. New Jersey does not recognize out-of-state gun licenses and aggressively enforces its own gun laws.[199]

Elections

| Year | Republican | Democratic |

|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 41.20% 1,583,058 | 54.79% 2,105,250 |

| 2012 | 40.62% 1,478,088 | 58.34% 2,122,786 |

| 2008 | 41.61% 1,613,207 | 57.14% 2,215,422 |

| 2004 | 46.24% 1,670,003 | 52.92% 1,911,430 |

| 2000 | 40.29% 1,284,173 | 56.13% 1,788,850 |

| 1996 | 35.86% 1,103,078 | 53.72% 1,652,329 |

| 1992 | 40.58% 1,356,865 | 42.95% 1,436,206 |

| 1988 | 56.24% 1,743,192 | 42.60% 1,320,352 |

| 1984 | 60.09% 1,933,630 | 39.20% 1,261,323 |

| 1980 | 51.97% 1,546,557 | 38.56% 1,147,364 |

| 1976 | 50.08% 1,509,688 | 47.92% 1,444,653 |

| 1972 | 61.57% 1,845,502 | 36.77% 1,102,211 |

| 1968 | 46.10% 1,325,467 | 43.97% 1,264,206 |

| 1964 | 33.86% 963,843 | 65.61% 1,867,671 |

| 1960 | 49.16% 1,363,324 | 49.96% 1,385,415 |

| 1956 | 64.68% 1,606,942 | 34.23% 850,337 |

| 1952 | 56.81% 1,374,613 | 41.99% 1,015,902 |

| 1948 | 50.33% 981,124 | 49.96% 1,385,415 |

In past elections, New Jersey was a Republican bastion, but recently has become a Democratic stronghold. Currently, New Jersey Democrats have majority control of both houses of the New Jersey Legislature (Senate, 24–16, and Assembly, 47–33), a 7–5 split of the state's twelve seats in the U.S. House of Representatives, and both U.S. Senate seats. Although the Democratic Party is very successful statewide, the state had a Republican governor from 1994 to 2002, as Christine Todd Whitman won twice with 47% and 49% of the votes, and in the 2009 gubernatorial election, Republican Chris Christie defeated incumbent Democrat Jon Corzine with 48%. In the 2013 gubernatorial election, Christie won reelection with over 60% of the votes. Because each candidate for lieutenant governor runs on the same ticket as the party's candidate for governor, the current Governor and Lieutenant Governor are members of the Democratic Party. The governor's appointments to cabinet and non-cabinet positions may be from either party; for instance, the Attorney General is a Democrat.

In federal elections, the state leans heavily towards the Democratic Party. For many years in the past, however, it was a Republican stronghold, having given comfortable margins of victory to the Republican candidate in the close elections of 1948, 1968, and 1976. New Jersey was a crucial swing state in the elections of 1960, 1968, and 1992. The last elected Republican to hold a Senate seat from New Jersey was Clifford P. Case in 1979. Newark Mayor Cory Booker was elected in October 2013 to join Robert Menendez to make New Jersey the first state with concurrent serving black and Latino U.S. senators.[201]

The state's Democratic strongholds include Camden County, Essex County (typically the state's most Democratic county—it includes Newark, the state's largest city), Hudson County (the second-strongest Democratic county, including Jersey City, the state's second-largest city); Mercer County (especially around Trenton and Princeton), Middlesex County, and Union County (including Elizabeth, the state's fourth-largest city).[202]