Second Barbary War

| Second Barbary War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Barbary Wars | |||||||

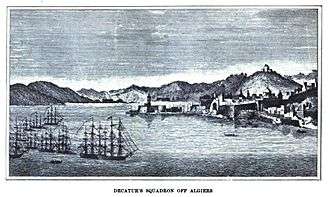

Decatur's Squadron off Algiers. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

James Madison Stephen Decatur, Jr. James C. George |

Mohamed Kharnadji † Omar Agha Reis Hamidou † | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 10 warships |

1 brig 1 frigate | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

10 killed 30 wounded [1] |

53 killed 486 captured | ||||||

The Second Barbary War (1815) was fought between the United States and the North African Barbary Coast states of Tripoli, Tunis, and Ottoman Algeria. The war ended when the United States Senate ratified Commodore Stephen Decatur’s Algerian treaty on December 5, 1815.[2] However, Dey Omar Agha of Algeria repudiated the US treaty, refused to accept the terms of peace that had been ratified by the Congress of Vienna, and threatened the lives of all Christian inhabitants of Algiers. William Shaler was the US commissioner in Algiers who had negotiated alongside Decatur, but he had to flee aboard British vessels and watch rockets and cannon shot fly over his house "like hail"[3] during the Bombardment of Algiers (1816). He negotiated a new treaty in 1816 which was not ratified by the Senate until February 11, 1822 because of an oversight.[4]

After the end of the war, the United States and European nations stopped paying tribute to the pirate states; this marked the beginning of the end of piracy in that region, which had been rampant in the days of Ottoman domination during the 16th–18th centuries. The western nations built ever more sophisticated and expensive ships which the Barbary pirates could not match in numbers or technology.[5]

Background

The First Barbary War (1801–05) had led to an uneasy truce between the US and the Barbary states, but American attention turned to Britain and the War of 1812. The Barbary pirates took the opportunity to return to their practice of attacking American and European merchant vessels in the Mediterranean Sea and holding the crews for ransom. At the same time, the major European powers were still involved in the Napoleonic Wars, which did not fully end until 1815.

At the conclusion of the War of 1812, however, the United States returned to the problem of Barbary piracy. On 3 March 1815, the United States Congress authorized deployment of naval power against Algiers, and the squadron under the command of Commodore Stephen Decatur set sail on 20 May. It consisted of USS Guerriere (flagship), Constellation, Macedonia, Epervier, Ontario, Firefly, Spark, Flambeau, Torch, and Spitfire.[6]

Shortly after departing Gibraltar en route to Algiers, Decatur's squadron encountered the Algerian flagship Meshuda and captured it in the Battle off Cape Gata, and they captured the Algerian brig Estedio in the Battle off Cape Palos. By the final week of June, the squadron had reached Algiers and had initiated negotiations with the Dey. The United States made persistent demands for compensation, mingled with threats of destruction, and the Dey capitulated. He signed a treaty aboard the Guerriere in the Bay of Algiers on 3 July 1815, in which Decatur agreed to return the captured Meshuda and Estedio. The Algerians returned all American captives, estimated to be about 10, in exchange for about 500 subjects of the Dey.[7] Algeria also paid $10,000 for seized shipping. The treaty guaranteed no further tributes by the United States[8] and granted the United States full shipping rights in the Mediterranean Sea.

Aftermath

In early 1816, Britain undertook a diplomatic mission, backed by a small squadron of ships of the line, to Tunis, Tripoli, and Algiers to convince the Deys to stop their piracy and free enslaved European Christians. The Beys of Tunis and Tripoli agreed without any resistance, but the Dey of Algiers was more recalcitrant, and the negotiations were stormy. The leader of the diplomatic mission, Edward Pellew, 1st Viscount Exmouth, believed that he had negotiated a treaty to stop the slavery of Christians and returned to England. However, just after the treaty was signed, Algerian troops massacred 200 Corsican, Sicilian and Sardinian fishermen who had been classified as under British protection. This caused outrage in Britain and Europe, and Exmouth's negotiations were seen as a failure.[9]

As a result, Exmouth was ordered to sea again to complete the job and punish the Algerians. He gathered a squadron of five ships of the line, reinforced by a number of frigates, later reinforced by a flotilla of six Dutch ships. On 27 August 1816, following a round of failed negotiations, the fleet delivered a punishing nine-hour bombardment of Algiers. The attack immobilized many of the Dey's corsairs and shore batteries, forcing him to accept a peace offer of the same terms as he had rejected the day before. Exmouth warned that if these terms were not accepted, he would continue the action. The Dey accepted the terms, but Exmouth had been bluffing; his fleet had already spent all its ammunition.[10]

A treaty was signed on 24 September 1816. The British Consul and 1,083 other Christian slaves were freed, and the U.S. ransom money repaid.

After the First Barbary War, the European nations had been engaged in warfare with one another (and the U.S. with the British). However, in the years immediately following the Second Barbary War, there was no general European war. This allowed the Europeans to build up their resources and challenge Barbary power in the Mediterranean without distraction. Over the following century, Algiers and Tunis were colonized by France in 1830 and 1881, respectively. In 1835, Tripoli returned to the control of the Ottoman Empire.

In 1911, taking advantage of the power vacuum left by the fading Ottoman Empire, Italy assumed control of Tripoli. Europeans remained in control of colonial governments in eastern North Africa until the mid-20th century. By then the iron-clad warships of the late 19th century and dreadnoughts of the early 20th century ensured European dominance of the Mediterranean sea.

See also

- Bombardment of Algiers (1816)

- Military history of the United States

- Barbary treaties

- US President James Madison

- 2011 military intervention in Libya, termed "Third Barbary War" by media[11]

- First Barbary War

Further reading

- Toll, Ian W. (March 17, 2008). Six Frigates: The Epic History of the Founding of the U.S. Navy. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0393330328.

References

- ↑ "Les Corsaires des Régences barbaresques - Page 6" (in French).

- ↑ "Milestones: 1801–1829 - Office of the Historian". history.state.gov. Retrieved 2016-05-02.

- ↑ Taylor, Stephen (2012). Commander: The Life and Exploits of Britain's Greatest Frigate Captain. London: faber and faber. p. 289. ISBN 978-0-571-27711-7.

- ↑ "Milestones: 1801–1829 - Office of the Historian". history.state.gov. Retrieved 2016-05-02.

- ↑ Leiner, Frederic C. (2007). The End of Barbary Terror, America's 1815 War against the Pirates of North Africa. Oxford University Press, 2007. pp. 39–50. ISBN 978-0-19-532540-9.

- ↑ Allen, Gardner Weld (1905). Our Navy and the Barbary Corsairs. Boston, New York and Chicago: Houghton Mifflin & Co. p. 281.

- ↑ "the United States according to the usages of civilized nations requiring no ransom for the excess of prisoners in their favor." (Article 3)

- ↑ "It is distinctly understood between the Contracting parties, that no tribute either as biennial presents, or under any other form or name whatever, shall ever be required by the Dey and Regency of Algiers from the United States of America on any pretext whatever." (Article 2)

- ↑ Taylor, Stephen (2012). Commander: The Life and Exploits of Britain's Greatest Frigate Captain. London: faber and faber. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-571-27711-7.

- ↑ Taylor, Stephen (2012). Commander: The Life and Exploits of Britain's Greatest Frigate Captain. London: faber and faber. p. 292. ISBN 978-0-571-27711-7.

- ↑ Appelbaum, Yoni (21 March 2011). "The Third Barbary War". The Atlantic. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

Sources

- Adams, Henry. History of the United States of America During the Administrations of Thomas Jefferson. Originally published 1891; Library of America edition 1986. ISBN 0-940450-34-8

- Lambert, Frank The Barbary Wars: American Independence in the Atlantic World New York: Hill and Wang, 2005

- London, Joshua E.Victory in Tripoli: How America's War with the Barbary Pirates Established the U.S. Navy and Shaped a Nation New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2005

- Oren, Michael B. Power, Faith, and Fantasy: The United States in the Middle East, 1776 to 2006. New York: W.W. Norton & Co, 2007. ISBN 978-0-393-33030-4

External links

- Barbary Warfare

- Treaties with The Barbary Powers: 1786–1836

- Text of the treaty signed in Algiers 30 June And 3 July 1815

- The Barbary Wars at the Clements Library: An online exhibit on the Barbary Wars with images and transcriptions of primary documents from the period.

- Victory in Tripoli: Lessons for the War on Terrorism

- Tripoli: The United States’ First War on Terror

- Victory In Tripoli

- When Europeans Were Slaves