Tear gas

.jpg)

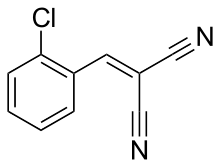

Tear gas, formally known as a lachrymator agent or lachrymator (from the Latin lacrima, meaning "tear"), sometimes colloquially known as mace,[NB 1] is a chemical weapon that causes severe eye and respiratory pain, skin irritation, bleeding, and even blindness. In the eye, it stimulates the nerves of the lacrimal gland to produce tears. Common lachrymators include pepper spray (OC gas), PAVA spray (nonivamide), CS gas, CR gas, CN gas (phenacyl chloride), bromoacetone, xylyl bromide, syn-propanethial-S-oxide (from onions), and Mace (a branded mixture).

Lachrymatory agents are commonly used for riot control. Their use in warfare is prohibited by various international treaties. During World War I, increasingly toxic lachrymatory agents were used.

Effects

Tear "gas" consists of aerosolized solid compounds, not gas.[1] Tear gas works by irritating mucous membranes in the eyes, nose, mouth and lungs, and causes crying, sneezing, coughing, difficulty breathing, pain in the eyes, and temporary blindness. With CS gas, symptoms of irritation typically appear after 20–60 seconds of exposure[2] and commonly resolve within 30 minutes of leaving (or being removed from) the area.[3] With pepper spray (also called "oleoresin capsicum", capsaicinoid or OC gas), the onset of symptoms, including loss of motor control, is almost immediate.[3] There can be considerable variation in tolerance and response, according to the National Research Council (US) Committee on Toxicology.[4]

The California Poison Control System analyzed 3,671 reports of pepper spray injuries between 2002 and 2011.[5] Severe symptoms requiring medical evaluation were found in 6.8% of people, with the most severe injuries to the eyes (54%), respiratory system (32%) and skin (18%). The most severe injuries occurred in law enforcement training, intentionally incapacitating people, and law enforcement (whether of individuals or crowd control).[5]

Lachrymators are thought to act by attacking sulfhydryl functional groups in enzymes. One of the most probable protein targets is the TRPA1 ion channel that is expressed in sensory nerves (trigeminal nerve) of the eyes, nose, mouth and lungs.

Risks

As with all non-lethal, or less-lethal weapons, there is some risk of serious permanent injury or death when tear gas is used.[6][7][1] This includes risks from being hit by tear gas cartridges, which include severe bruising, loss of eyesight, skull fracture, and even death.[8] A case of serious vascular injury from tear gas shells has also been reported from Iran, with high rates of associated nerve injury (44%) and amputation (17%),[9] as well as instances of head injuries in young people.[10]

While the medical consequences of the gases themselves are typically limited to minor skin inflammation, delayed complications are also possible: people with pre-existing respiratory conditions such as asthma, who are particularly at risk, are likely to need medical attention[2] and may sometimes require hospitalization or even ventilation support.[11] Skin exposure to CS may cause chemical burns[12] or induce allergic contact dermatitis.[2][3] When people are hit at close range or are severely exposed, eye injuries involving scarring of the cornea can lead to a permanent loss in visual acuity.[13] Frequent or high levels of exposure carry increased risks of respiratory illness.[1]

Expiration

Reports of expired tear gas canisters picked up by protesters in Egypt led to theories that it could be more toxic, but Steve Wright of Leeds Metropolitan University said if enough time has elapsed that the chemicals have broken down inside the can, then it makes the canister less effective.[14] However, a study carried out by Mónica Kräuter, a Venezuelan professor of Simón Bolívar University, collected thousands of tear gas canisters fired by Venezuelan authorities in 2014, showed that 72% of the tear gas used was expired and noted that expired tear gas "breaks down into cyanide oxide, phosgenes and nitrogens that are extremely dangerous".[15]

Use

Warfare

Use of tear gas in warfare (as with all other chemical weapons) is prohibited by various international treaties[NB 2] that most states have signed. Police and private self-defense use is not banned in the same manner. Armed forces can legally use tear gas for drills (practicing with gas masks) and for riot control. First used in 1914, xylyl bromide was a popular tearing agent since it was easily prepared.

The US Chemical Warfare Service developed tear gas grenades for use in riot control in 1919.[16]

Riot control

Certain lachrymatory agents are often used by police to force compliance, most notably tear gas.[7] In some countries (e.g., Finland, Australia, and the United States), another common substance is mace. The self-defense weapon form of mace is based on pepper spray, and comes in small spray cans, and versions including CS are manufactured for police use.[17] Xylyl bromide, CN and CS are the oldest of these agents, and CS is the most widely used. CN has the most recorded toxicity.[2] Tear gas exposure is a standard in Australia for military, police and prison officer training programs.

Typical manufacturer warnings on tear gas cartridges state "Danger: Do not fire directly at person(s). Severe injury or death may result."[18] Such warnings are not necessarily respected, and in some countries, disrespecting these warnings is routine. In the 2013 protests in Turkey, there were hundreds of injuries among protesters targeted with tear gas projectiles. In the Israeli-occupied territories, Israeli soldiers have been routinely documented by Israeli human rights group in firing direct tear gas canisters at activists, some of which resulted in fatalities.[19][20] Amnesty International criticized the usage of tear gas by Venezuelan authorities noting canisters being fired directly at individuals, causing the death of at least one demonstrator, while also being shot into residential buildings.[21]

However, tear gas guns do not have a manual setting to adjust the range of fire. The only way to adjust the projectile's range is to aim towards the ground at the correct angle. Incorrect aim will send the capsules away from the targets, causing risk for non-targets instead.[22] For example, this occurred during the 2013 protests in Brazil, 2014 Hong Kong Protests and both the 2014 and 2017 Venezuelan protests.

Tear gas being used against opposition protesters during the 2014 Venezuelan protests

Tear gas being used against opposition protesters during the 2014 Venezuelan protests Tear gas grenade returned to Israeli soldiers using sling during Palestinian weekly protest in Ni'lin, July 2014

Tear gas grenade returned to Israeli soldiers using sling during Palestinian weekly protest in Ni'lin, July 2014

Counter-measures

A variety of protective equipment may be used, including gas masks and respirators. In riot control situations, protesters sometimes use equipment (aside from simple rags or clothing over the mouth) such as swimming goggles and adapted water bottles.[23]

It has been suggested that "The use of masks that filter solid particles is effective, if and only if, the membrane manages to catch particles with sizes smaller than 60 microns".[14]

Activists in the United States, the Czech Republic, Venezuela and Turkey have reported using antacid solutions such as Maalox diluted with water to repel effects of tear gas attacks[24][25][26] with Venezuelan chemist Mónica Kräuter recommending the usage of diluted antacids as well as baking soda.[14][27] There have also been reports of these antacids being helpful for tear gas,[28] and for capsaicin-induced skin pain.[29]

Treatment

There is no specific antidote to common tear gases.[2][30] Getting clear of gas and into fresh air is the first line of action.[2] Removing contaminated clothing and avoiding shared use of contaminated towels could help reduce skin reactions.[31] Immediate removal of contact lenses has also been recommended, as they can retain particles.[31][30]

Once a person has been exposed, there are a variety of methods to remove as much chemical possible and relieve symptoms.[2] The standard first aid for burning solutions in the eye is irrigation (spraying or flushing out) with water.[2][32] There are reports that water may increase pain from CS gas, but the balance of limited evidence currently suggests water or saline are the best options.[30][28][33] Some evidence suggests that Diphoterine[34] solution, a first aid product for chemical splashes, may help with ocular burns or chemicals in the eye.[32][35]

Bathing and washing the body vigorously with soap and water can remove particles that adhered to the skin while clothes, shoes and accessories that have came into contact with vapors must be washed well since all untreated particles can remain active for up to a week.[14] Some advocate using fans or hair dryers to evaporate the spray, but this has not been shown to be better than washing out the eyes and it may spread contamination.[30]

Anticholinergics can work like some Antihistamines as they reduce lacrymation, decrease salivation, as they act as an antisialagogue and for overall nose discomfort as they are used to treat allergic reactions in the nose (e.g., itching, runny nose, and sneezing)

Oral analgesics may help relieve eye pain.[30]

Home remedies

Vinegar, petroleum jelly, milk and lemon juice solutions have also been used by activists.[36][37][38][39] It is unclear how effective these remedies are. In particular, vinegar itself can burn the eyes and prolonged inhalation can also irritate the airways.[40] Though vegetable oil and vinegar have also been reported as helping relieve burning caused by pepper spray,[31] Krauter does not suggest the usage of vinegar, toothpaste or menthol creams, stating that "they trap the particles emanating from the gas near the airways and make it more feasible to inhale".[14] A small trial of baby shampoo for washing out the eyes did not show any benefit.[30]

See also

Notes

- ↑ "Mace" is a brand name for a tear gas spray

- ↑ e.g. the Geneva Protocol of 1925: 'Prohibited the use of "asphyxiating gas, or any other kind of gas, liquids, substances or similar materials"'

References

- 1 2 3 Rothenberg, C; Achanta, S; Svendsen, ER; Jordt, SE (August 2016). "Tear gas: an epidemiological and mechanistic reassessment". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1378 (1): 96–107. Bibcode:2016NYASA1378...96R. doi:10.1111/nyas.13141. PMC 5096012. PMID 27391380.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Schep, LJ; Slaughter, RJ; McBride, DI (Dec 30, 2013). "Riot control agents: the tear gases CN, CS and OC--a medical review". Journal of the Royal Army Medical Corps. doi:10.1136/jramc-2013-000165. PMID 24379300.

- 1 2 3 Smith, J; Greaves, I (March 2002). "The use of chemical incapacitant sprays: a review" (PDF). J Trauma. 52 (3): 595–600. doi:10.1097/00005373-200203000-00036. PMID 11901348. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- ↑ National Research Council (US) Committee on Toxicology (2011). "National Research Council (US) Committee on Acute Exposure Guideline". PMID 24983066.

- 1 2 Kearney, T; Hiatt, P; Birdsall, E; Smollin, C (Jul–Sep 2014). "Pepper spray injury severity: ten-year case experience of a poison control system". Prehospital emergency care : official journal of the National Association of EMS Physicians and the National Association of State EMS Directors. 18 (3): 381–6. doi:10.3109/10903127.2014.891063. PMID 24669935.

- ↑ Heinrich U (September 2000). "Possible lethal effects of CS tear gas on Branch Davidians during the FBI raid on the Mount Carmel compound near Waco, Texas" (PDF). Prepared for The Office of Special Counsel John C. Danforth.

- 1 2 Hu H, Fine J, Epstein P, Kelsey K, Reynolds P, Walker B (August 1989). "Tear gas--harassing agent or toxic chemical weapon?" (PDF). JAMA. 262 (5): 660–3. doi:10.1001/jama.1989.03430050076030. PMID 2501523. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-10-29.

- ↑ Clarot F, Vaz E, Papin F, Clin B, Vicomte C, Proust B (October 2003). "Lethal head injury due to tear-gas cartridge gunshots". Forensic Sci. Int. 137 (1): 45–51. doi:10.1016/S0379-0738(03)00282-2. PMID 14550613.

- ↑ Wani, ML; Ahangar, AG; Lone, GN; Singh, S; Dar, AM; Bhat, MA; Ashraf, HZ; Irshad, I (Mar 2011). "Vascular injuries caused by tear gas shells: surgical challenge and outcome". Iranian journal of medical sciences. 36 (1): 14–7. PMC 3559117. PMID 23365472.

- ↑ Wani, AA; Zargar, J; Ramzan, AU; Malik, NK; Qayoom, A; Kirmani, AR; Nizami, FA; Wani, MA (2010). "Head injury caused by tear gas cartridge in teenage population". Pediatric neurosurgery. 46 (1): 25–8. doi:10.1159/000314054. PMID 20453560.

- ↑ Carron, PN; Yersin, B (19 June 2009). "Management of the effects of exposure to tear gas". BMJ. 338: b2283. doi:10.1136/bmj.b2283. PMID 19542106.

- ↑ Worthington E, Nee PA (May 1999). "CS exposure—clinical effects and management". J Accid Emerg Med. 16 (3): 168–70. doi:10.1136/emj.16.3.168. PMC 1343325. PMID 10353039.

- ↑ Oksala A, Salminen L (December 1975). "Eye injuries caused by tear-gas hand weapons". Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh). 53 (6): 908–13. doi:10.1111/j.1755-3768.1975.tb00410.x. PMID 1108587.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Who, What, Why: How dangerous is tear gas?". BBC. 25 November 2011. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- ↑ "Bombas lacrimógenas que usa el gobierno están vencidas y emanan cianuro (+ recomendaciones)". La Patilla (in Spanish). 8 April 2017. Retrieved 9 April 2017.

- ↑ Jones DP (April 1978). "From Military to Civilian Technology: The Introduction of Tear Gas for Civil Riot Control". Technology and Culture. 19 (2): 151–168. doi:10.2307/3103718. JSTOR 3103718.

- ↑ "Mace pepper spray". Mace (manufacturer). Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ↑ Smith E (2011-01-28). "Controversial tear gas canisters made in the USA". Africa. CNN.com.

- ↑ "Israeli soldiers continue firing tear gas canisters directly at human targets, despite the army's denials". B'tselem. Retrieved 27 December 2013.

- ↑ "Israeli MAG Corps closes file in Mustafa Tamimi killing, stating the tear-gas canister that killed him was fired legally". B'tselem. Retrieved 27 December 2013.

- ↑ "Amnesty Reports Dozens of Venezuela Torture Accounts". Bloomberg. Retrieved 13 April 2014.

- ↑ Turkish Doctors' Association, 16 June 2013, TÜRK TABİPLERİ BİRLİĞİ’NDEN ACİL ÇAĞRI !

- ↑ "Gezi park protesters bring handmade masks to counter police tear-gas rampage". Hurriyet Daily News.

- ↑ David Ferguson (2011-09-28). "'Maalox'-and-water solution used as anti-tear gas remedy by protesters". Raw Story.

- ↑ "Medical information from Prague 2000". Archived from the original on 2014-10-18.

- ↑ Ece Temelkuran (2013-06-03). "Istanbul is burning". Occupy Wall Street.

- ↑ "Prof USB Mónica Kräuter, Cómo reaccionar ante las bombas lacrimógenas". Tururutururu (in Spanish). 26 May 2017. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- 1 2 Carron, PN; Yersin, B (19 June 2009). "Management of the effects of exposure to tear gas". BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 338: b2283. doi:10.1136/bmj.b2283. PMID 19542106.

- ↑ Kim-Katz, SY; Anderson, IB; Kearney, TE; MacDougall, C; Hudmon, KS; Blanc, PD (June 2010). "Topical antacid therapy for capsaicin-induced dermal pain: a poison center telephone-directed study". The American journal of emergency medicine. 28 (5): 596–602. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2009.02.007. PMID 20579556.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Kim, YJ; Payal, AR; Daly, MK (2016). "Effects of tear gases on the eye". Survey of ophthalmology. 61 (4): 434–42. doi:10.1016/j.survophthal.2016.01.002. PMID 26808721.

- 1 2 3 Yeung, MF; Tang, WY (6 November 2015). "Clinicopathological effects of pepper (oleoresin capsicum) spray". Hong Kong medical [Xianggang yi xue za zhi / Hong Kong Academy of Medicine]. 21: 542–52. doi:10.12809/hkmj154691. PMID 26554271.

- 1 2 Chau JP, Lee DT, Lo SH (August 2012). "A systematic review of methods of eye irrigation for adults and children with ocular chemical burns". Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 9 (3): 129–38. doi:10.1111/j.1741-6787.2011.00220.x. PMID 21649853.

- ↑ Brvar, M (24 March 2015). "Chlorobenzylidene malononitrile tear gas exposure: Rinsing with amphoteric, hypertonic, and chelating solution". Human & Experimental Toxicology. 35: 213–8. doi:10.1177/0960327115578866. PMID 25805600.

- ↑ Diphoterine

- ↑ Viala B, Blomet J, Mathieu L, Hall AH (July 2005). "Prevention of CS 'tear gas' eye and skin effects and active decontamination with Diphoterine: preliminary studies in 5 French Gendarmes". J Emerg Med. 29 (1): 5–8. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2005.01.002. PMID 15961000.

- ↑ Agence France-Press. "Tear gas and lemon juice in the battle for Taksim Square". NDTV. Retrieved 23 June 2013.

- ↑ Megan Doyle (24 June 2013). "Turks in Pittsburgh concerned for their nation". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

- ↑ Tim Arango (15 June 2013). "Police Storm Park in Istanbul, Setting Off a Night of Chaos". New York Times.

- ↑ Gareth Hughes (25 June 2013). "Denbigh man tear gassed". The Free Press.

- ↑ Toxic Use Reduction Institute. "Vinegar EHS". Toxics Use Reduction Institute, UMAss Lowell. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

Further reading

- Feigenbaum, Anna (2016). Tear Gas: From the Battlefields of WWI to the Streets of Today. New York and London: Verso. ISBN 978-1-784-78026-5.

External links

| Look up tear gas in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lachrymatory agents. |

- BBC information about CS gas

- How to combat CS gas at eco-action.org

- Brône, B; et al. (1 September 2008). "Tear gasses CN, CR, and CS are potent activators of the human TRPA1 receptor". Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 231 (2): 150–6. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2008.04.005. PMID 18501939.