Staten Island

| Staten Island Richmond County | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Borough of New York City County of New York State | |||

_under_the_Verrazano_Narrows_Bridge.jpg) The Verrazano-Narrows Bridge, looking toward Staten Island from Brooklyn | |||

| |||

| Nickname(s): The Forgotten Borough, Shaolin | |||

|

Interactive map of Staten Island | |||

| Coordinates: 40°34′19″N 74°8′49″W / 40.57194°N 74.14694°WCoordinates: 40°34′19″N 74°8′49″W / 40.57194°N 74.14694°W | |||

| Country |

| ||

| State |

| ||

| County | Richmond (coterminous) | ||

| City | New York City | ||

| Settled | 1661 | ||

| Named for | Charles Lennox, 1st Duke of Richmond (Richmond County) | ||

| Government | |||

| • Type | Borough (New York City) | ||

| • Borough president |

James Oddo (R) — (Borough of Staten Island) | ||

| • District Attorney |

Michael McMahon (D) — (Richmond County) | ||

| Area | |||

| • Total | 102.5 sq mi (265 km2) | ||

| • Land | 58.5 sq mi (152 km2) | ||

| • Water | 44 sq mi (110 km2) 43% | ||

| Population (2017) | |||

| • Total | 479,458[1] | ||

| • Density | 8,195.9/sq mi (3,164.5/km2) | ||

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern Standard Time) | ||

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (Eastern Daylight Time) | ||

| ZIP Code prefix | 103 | ||

| Area code | 718/347/929, 917 | ||

| Website |

www | ||

Staten Island /ˌstætən

The North Shore—especially the neighborhoods of St. George, Tompkinsville, Clifton, and Stapleton—is the most urban part of the island; it contains the designated St. George Historic District and the St. Paul's Avenue-Stapleton Heights Historic District, which feature large Victorian houses. The East Shore is home to the 2.5-mile (4 km) F.D.R. Boardwalk, the fourth-longest boardwalk in the world.[6] The South Shore, site of the 17th-century Dutch and French Huguenot settlement, developed rapidly beginning in the 1960s and 1970s and is now mostly suburban in character. The West Shore is the least populated and most industrial part of the island.

Motor traffic can reach the borough from Brooklyn via the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge and from New Jersey via the Outerbridge Crossing, Goethals Bridge, and Bayonne Bridge. Staten Island has Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) bus lines and an MTA rapid transit line, the Staten Island Railway, which runs from the ferry terminal at St. George to Tottenville. Staten Island is the only borough that is not connected to the New York City Subway system. The free Staten Island Ferry connects the borough across New York Harbor to Manhattan and is a popular tourist attraction, providing views of the Statue of Liberty, Ellis Island, and Lower Manhattan.

Staten Island had the Fresh Kills Landfill, which was the world's largest landfill before closing in 2001,[7] although it was temporarily reopened that year to receive debris from the September 11 attacks.[8] The landfill is being redeveloped as Freshkills Park, an area devoted to restoring habitat; the park will become New York City's second largest public park when completed.[9]

New York City's five boroughs | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jurisdiction | Population | Land area | Density | |||

| Borough | County | Estimate (2017)[10] | square miles | square km | persons / sq. mi | persons / sq. km |

New York |

1,664,727 | 22.83 | 59.13 | 72,033 | 27,826 | |

Bronx |

1,471,160 | 42.10 | 109.04 | 34,653 | 13,231 | |

Kings |

2,648,771 | 70.82 | 183.42 | 37,137 | 14,649 | |

Queens |

2,358,582 | 108.53 | 281.09 | 21,460 | 8,354 | |

Richmond |

479,458 | 58.37 | 151.18 | 8,112 | 3,132 | |

| 8,622,698 | 302.64 | 783.83 | 28,188 | 10,947 | ||

| 19,849,399 | 47,214 | 122,284 | 416.4 | 159 | ||

Sources: [11] and see individual borough articles | ||||||

History

Native Americans

As in much of North America, human habitation appeared in the island fairly rapidly after the Wisconsin glaciation. Archaeologists have recovered tool evidence of Clovis culture activity dating from about 14,000 years ago. This evidence was first discovered in 1917 in the Charleston section of the island. Various Clovis artifacts have been discovered since then, on property owned by Mobil Oil.

The island was probably abandoned later, possibly because of the extirpation of large mammals on the island. Evidence of the first permanent Native American settlements and agriculture are thought to date from about 5,000 years ago,[12] although early archaic habitation evidence has been found in multiple locations on the island.[13]

Rossville points are distinct arrowheads that define a Native American cultural period that runs from the Archaic period to the Early Woodland period, dating from about 1500 to 100 BC. They are named for the Rossville section of Staten Island, where they were first found near the old Rossville Post Office building.[14]

At the time of European contact, the island was inhabited by the Raritan band of the Unami division of the Lenape. In Lenape, one of the Algonquian languages, Staten Island was called Aquehonga Manacknong, meaning "as far as the place of the bad woods", or Eghquhous, meaning "the bad woods".[15] The area was part of the Lenape homeland known as Lenapehoking. The Lenape were later called the "Delaware" by the English colonists because they inhabited both shores of what the English named the Delaware River.

The island was laced with Native American foot trails, one of which followed the south side of the ridge near the course of present-day Richmond Road and Amboy Road. The Lenape did not live in fixed encampments but moved seasonally, using slash and burn agriculture. Shellfish was a staple of their diet, including the Eastern oyster (Crassostrea virginica) abundant in the waterways throughout the present-day New York City region. Evidence of their habitation can still be seen in shell middens along the shore in the Tottenville section, where oyster shells larger than 12 inches (305 mm) are sometimes found.

Burial Ridge, a Lenape burial ground on a bluff overlooking Raritan Bay in Tottenville, is the largest pre-European burial ground in New York City. Bodies have been reported unearthed at Burial Ridge from 1858 onward. After conducting independent research, which included unearthing bodies interred at the site, ethnologist and archaeologist George H. Pepper was contracted in 1895 to conduct paid archaeological research at Burial Ridge by the American Museum of Natural History. The burial ground today is unmarked and lies within Conference House Park.

European settlement

The first recorded European contact on the island was in 1520 by Italian explorer Giovanni de Verrazzano who sailed through The Narrows on the ship La Dauphine and anchored for one night.

In 1609, English explorer Henry Hudson sailed into Upper New York Bay on his ship the Half Moon. The Dutch named the island Staaten Eylandt (literally "States Island") in honor of the Dutch parliament, which is still known as the Staten-Generaal ("States General"). The first permanent Dutch settlement of the New Netherland colony was made on Governor's Island in 1624, which they had used as a trading camp for more than a decade before. In 1626, the colony transferred to the island of Manhattan which was designated as the capital of New Netherland.

The Dutch did not establish a permanent settlement on Staaten Eylandt for many decades. From 1639 to 1655, Cornelis Melyn and David de Vries made three separate attempts to establish one there, but each time the settlement was destroyed in conflicts between the Dutch and the local tribe.[16] In 1661, the first permanent Dutch settlement was established at Oude Dorp (Dutch for "Old Village") by a small group of Dutch, Walloon, and French Huguenot families,[17] just south of the Narrows near South Beach. Many French Huguenots had gone to the Netherlands as refugees from the religious wars in France, suffering persecution for their Protestant faith, and some joined the emigration to New Netherland. At one point nearly a third of the residents of the Island spoke French.[18] The last vestige of Oude Dorp is the name of the present-day neighborhood of Old Town adjacent to Old Town Road.[19]

Staten Island was not spared the bloodshed which culminated in Kieft's War. In the summer of 1641 and in 1642 Native American tribes laid waste to Old Town.[20]

Richmond County

At the end of the Second Anglo-Dutch War in 1667, the Dutch ceded New Netherland to England in the Treaty of Breda, and the Dutch Staaten Eylandt, anglicized as "Staten Island", became part of the new English colony of New York.

In 1670, the Native Americans ceded all claims to Staten Island to the English in a deed to Governor Francis Lovelace. In 1671, in order to encourage an expansion of the Dutch settlements, the English resurveyed Oude Dorp (which became known as "Old Town") and expanded the lots along the shore to the south. These lots were settled primarily by Dutch families and became known as Nieuwe Dorp (meaning "New Village"), which later became anglicized as New Dorp.

Captain Christopher Billopp, after years of distinguished service in the Royal Navy, came to America in 1674 in charge of a company of infantry. The following year, he settled on Staten Island, where he was granted a patent for 932 acres (3.8 km2) of land. According to one version of an oft-repeated but inaccurate tale, Captain Billopp's seamanship secured Staten Island to New York, rather than to New Jersey: the island would belong to New York if the captain could circumnavigate it in one day, which he did. Mayor Michael Bloomberg perpetuated the myth by referring to it at a news conference in Brooklyn on February 20, 2007.[21]

In 1683, the colony of New York was divided into ten counties. As part of this process, Staten Island, as well as several minor neighboring islands, was designated as Richmond County. The name derives from the title of Charles Lennox, 1st Duke of Richmond, an illegitimate son of King Charles II.

In 1687 and 1688, the English divided the island into four administrative divisions based on natural features: the 5,100-acre (21 km2) manorial estate of colonial governor Thomas Dongan in the northeastern hills known as the "Lordship or Manner of Cassiltown", along with the North, South, and West divisions. These divisions later evolved into the four towns of Castleton, Northfield, Southfield, and Westfield. In 1698, the population was 727.[22]

The government granted land patents in rectangular blocks of eighty acres (320,000 m2), with the most desirable lands along the coastline and inland waterways. By 1708, the entire island had been divided up in this fashion, creating 166 small farms and two large manorial estates, the Dongan estate and a 1,600 acres (6.5 km2) parcel on the southwestern tip of the island belonging to Christopher Billopp.[12]

The first county seat was established in New Dorp in what was called Stony Brook at the time.[23] In 1729, the county seat was moved to the village of Richmond Town, located at the headwaters of the Fresh Kills near the center of the island. By 1771, the island's population had grown to 2,847.[22]

18th century and the American Revolution

The island played a significant role in the American Revolutionary War. On March 17, 1776, the British forces under Lord Howe evacuated Boston and sailed for Halifax, Nova Scotia. From Halifax, Howe prepared to attack New York City, which then consisted entirely of the southern end of Manhattan Island. General George Washington led the entire Continental Army to New York City in anticipation of the British attack. Howe used the strategic location of Staten Island as a staging ground for the invasion.

Over 140 British ships arrived over the summer of 1776 and anchored off the shores of Staten Island at the entrance to New York Harbor. The British soldiers and Hessian mercenaries numbered about 30,000. Howe established his headquarters in New Dorp at the Rose and Crown Tavern, near the junction of present New Dorp Lane and Amboy Road. There the representatives of the British government reportedly received their first notification of the Declaration of Independence.

In August 1776, the British forces crossed the Narrows to Brooklyn and outflanked the American forces at the Battle of Long Island, resulting in the British control of the harbor and the capture of New York City shortly afterwards. Three weeks later, on September 11, 1776, Lord Howe received a delegation of Americans consisting of Benjamin Franklin, Edward Rutledge, and John Adams at the Conference House on the southwestern tip of the island on the former estate of Christopher Billopp. However, the Americans refused a peace offer from Howe in exchange for withdrawing the Declaration of Independence, and the conference ended without an agreement.

On August 22, 1777, the Battle of Staten Island occurred between the British forces and several companies of the 2nd Canadian Regiment fighting alongside other American companies. The battle was inconclusive, though both sides surrendered over a hundred troops as prisoners. The Americans finally withdrew.

In early 1780, while the Kill Van Kull was frozen over, Lord Stirling led an unsuccessful Patriot raid from New Jersey on the western shore of Staten Island. It was repulsed in part by troops led by British Commander Francis Rawdon-Hastings, 1st Marquess of Hastings.

British forces remained on Staten Island for the remainder of the war. Most Patriots fled after the British occupation, and the sentiment of those who remained was predominantly Loyalist. Even so, the islanders found the demands of supporting the troops to be heavy. The British army kept headquarters in neighborhoods such as Bulls Head. Many buildings and churches were destroyed for their materials, and the military's demand for resources resulted in an extensive deforestation by the end of the war. The British army again used the island as a staging ground for its final evacuation of New York City on December 5, 1783. After their departure, many Loyalist landowners fled to Canada, and their estates were subdivided and sold.

19th century

On July 4, 1827, the end of slavery in New York state was celebrated at Swan Hotel, West Brighton. Rooms at the hotel were reserved months in advance as local abolitionists and prominent free blacks prepared for the festivities. Speeches, pageants, picnics, and fireworks marked the celebration, which lasted for two days.

In 1860, parts of Castleton and Southfield were made into a new town, Middletown. The Village of New Brighton in the town of Castleton was incorporated in 1866, and in 1872 the Village of New Brighton annexed all the remainder of the Town of Castleton and became coterminous with the town.

Consolidation with New York City

The towns of Staten Island were dissolved in 1898 with the consolidation of the City of Greater New York, as Richmond County became one of the five boroughs of the expanded city. Although consolidated into the City of Greater New York in 1898, the county sheriff of Staten Island maintained control of the jail system, unlike the other boroughs who had gradually transferred control of the jails to the Department of Correction. The jail system was not transferred until January 1, 1942. Today, Staten Island is the only borough without a New York City Department of Correction major detention center.

The construction of the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge, along with the other three major Staten Island bridges, created a new way for commuters and tourists to travel from New Jersey to Brooklyn, Manhattan, and areas farther east on Long Island. The network of highways running between the bridges has effectively carved up many of Staten Island's old neighborhoods. The bridge opened many areas of the borough to residential and commercial development, especially in the central and southern parts of the borough, which had been largely undeveloped. Staten Island's population doubled from about 221,000 in 1960 to about 443,000 in 2000.

Throughout the 1980s, a movement to secede from the city (notably championed by longtime New York State Senator and former Republican Party mayoral nominee John J. Marchi) steadily grew in popularity, reaching its peak during the mayoral term of David Dinkins. In a 1993 referendum, 65% voted to secede, but implementation was blocked in the State Assembly.[24]

In the 1980s, the United States Navy had a base on Staten Island called Naval Station New York. It had two sections: a Strategic Homeport in Stapleton and a larger section near Fort Wadsworth, where the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge enters the island. The base was closed in 1994 through the Base Realignment and Closure process because of its small size and the expense of basing personnel there.

Fresh Kills and its tributaries are part of the largest tidal wetland ecosystem in the region. Its creeks and wetlands have been designated a Significant Coastal Fish and Wildlife Habitat by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Opened along Fresh Kills as a "temporary landfill" in 1947, the Fresh Kills Landfill was a repository of trash for the city of New York. The landfill, once the world's largest man-made structure,[25] was closed in 2001,[26] but was briefly re-opened for the debris from Ground Zero following the September 11 attacks in 2001. It is being converted into a park. Plans for the park include a bird-nesting island, public roads, boardwalks, soccer and baseball fields, bridle paths, and a 5,000-seat stadium.[27] Today, freshwater and tidal wetlands, fields, birch thickets, and a coastal oak maritime forest, as well as areas dominated by non-native plant species, are all within the boundaries of Fresh Kills.

Timeline

17th century

- 1609 – Henry Hudson names island "Staaten Eylandt."[28]

- 1630 – Island granted by the Dutch West India Company to Michael Pauw.[29]

- 1636 – Part of the island granted by the Dutch West India Company to David Pietersen de Vries.[29]

- 1640

- Remaining part of the island granted by the Dutch West India Company to Cornelis Melyn.[30]

- Willem Kieft establishes the first distillery in North America. [31]

- 1641 – Settlement established by David Pietersen de Vries at Oude Dorp, New Netherland.[29]

- 1655–60 – Lenape attack and burn the last Cornelius Melyn/David de Vries attempt at settlement, capturing or killing the Dutch settlers

- 1664 – Island transferred from Dutch to British.[28]

- 1668 – Island becomes part of British Province of New York.[28]

- 1670 – Island's first church, for the Waldensian Evangelical Church, was established in Stony Brook (now New Dorp)

- 1698 – Island population reaches 727; slaves constitute 10%

18th century

- 1713 – St. Andrew's Church built.[32]

- 1727 – Richmond village becomes seat of Richmond County, New York.[29]

- 1740 – Moravian Cemetery established.[33]

- 1763 – Moravian Church built.[32]

- 1776

- July 3: British military occupation begins.[28]

- September 11: Staten Island Peace Conference held.

- 1777 – August 22: Battle of Staten Island occurs.

- 1783 – November 25: British military occupation ends.[28]

- 1788 – Towns of Castleton, Northfield, Southfield, and Westfield established.[30][34]

- 1792 – Reformed Dutch Church incorporated.[32]

- 1799 – Quarantine established.[30]

19th century

- 1802 – Episcopal Church (Northfield) built.[35]

- 1817 – Richmond Turnpike Company ferry begins operating to New York City.

- 1823 – Population: 6,135.[36]

- 1825 – Old Staten Island Dyeing Establishment incorporated (approximate date).[37]

- 1826 – Agricultural Society organized.[38]

- 1828 – Fort Tompkins Light commissioned.

- 1833 – Sailors' Snug Harbor opens for retired merchant seamen.

- 1836 - Aaron Burr dies in a boardinghouse in Port Richmond.

- 1837

- 1839 – St. Peter's Church established, first Roman Catholic parish on the Island.

- 1840 – Bethel United Methodist Church (Tottenville) built.

- 1842 – Woodrow Methodist Church built.

- 1844 – Dutch Reformed Church on Staten Island built.

- 1845 – Moravian Church built.[40]

- 1847 – Richmond County Law Library[41] and Marine's Family Asylum founded.[30]

- 1848 – St. Peter's Cemetery established.

- 1855 – St. Joseph's Church established.

- 1856

- Staten Island Historical Society founded.[42]

- New Dorp Light commissioned.[30]

- 1860

- Staten Island Rapid Transit Railway begins operating.

- Town of Middletown formed from parts of Castleton and Southfield.[30]

- Fort Tompkins built.

- 1861 – Battery Weed fortification built.

- 1865 – Church of the Holy Comforter built.

- 1866

- Brighton Heights Reformed Church and St. Paul's Memorial Church (Staten Island, New York) built.

- Staten Island Leader newspaper begins publication.[43]

- Villages of Edgewater and Port Richmond incorporated.[30]

- 1869 – Tottenville and S.R. Smith Infirmary incorporated.[30][37]

- 1870

- 1871

- July 30: Westfield ferry disaster.

- New Brighton Village Hall built.

- 1874 - Tennis introduced to North America for the first time on the island.

- 1878 – St. Philip's Baptist Church, the first Black church on Staten Island, opens.

- 1880 - Staten Island Water Supply Company established.[37]

- 1881 – Natural Science Association founded.[46]

- 1883

- November: Richmond County bicentennial.[47]

- Wagner College founded in Rochester. It does not move to Staten Island until 1918.

- 1884 – Saint George Terminal and Staten Island Academy open.

- 1886

- Richmond County Advance newspaper begins publication.

- Richmond County Savings Bank and St. John's Guild Children's Hospital (New Dorp) established.[48]

- 1888 – Richmond County Country Club opens.[49]

- 1890 – Population: 51,693.[29]

- 1894 – Calvary Presbyterian Church built.

- 1898

- January 1: Island becomes Borough of Richmond of New York City.[29]

- George Cromwell becomes Borough President.

20th century

- 1900 – Population: 67,021.[29]

- 1901 – June 14: Northfield ferry accident.

- 1902 – Curtis High School begins construction.

- 1903 – Fort Wadsworth Light commissioned. Notre Dame Academy (Grymes Hill) established.[48]

- 1904 – Christ Church New Brighton (Episcopal) built. Curtis High School is established.

- 1906 – Staten Island Borough Hall built. Happyland Amusement Park opens.

- 1907 – Public Museum of the Staten Island Institute of Arts and Sciences established.[50]

- Temple Emanu-El built.

- Procter & Gamble factory (Milliken) opens.[48]

- 1910 – Population: 85,969.[29]

- 1915 - Staten Island Stapletons football team founded; later plays in the National Football League from 1929 to 1932.

- 1919 – Richmond County Courthouse built.

- 1923 – Staten Island Tunnel construction begins.

- 1924

- 1926

- Staten Island Armory built.[52]

- Conference House Park established.

- Fire destroys St. George ferry terminal, killing three and causing $22 million in damage.

- 1927 – Port Richmond High School established.

- 1928 – Outerbridge Crossing (bridge) opens to Perth Amboy, New Jersey. Goethals Bridge opens to Elizabeth, New Jersey.

- 1929 – St. George Theater built.

- 1930 – Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Church opens.[53]

- 1931 – Bayonne Bridge opens to Bayonne, New Jersey.[54]

- 1933 – Notre Dame College (Staten Island) opens.

- 1935 – South Beach-Franklin Delano Roosevelt Boardwalk constructed.

- 1936 – Staten Island Zoo opens. Robin Road Trestle (bridge) built. Foreign trade zone established on Staten Island.[55]

- 1937 – Our Lady of Mount Carmel Grotto construction begins.

- 1938 – Lane Theater opens in New Dorp.[56]

- 1941 – Beachland Amusements opens.

- 1942 – January 1: Staten Island jails transferred from the County Sheriff's Department to the NYC Department of Corrections

- 1947 – Fresh Kills Landfill, Willowbrook State School, and Jacques Marchais Museum of Tibetan Art established.

- 1949 – Great Kills Park opens.

- 1950 – Population: 191,555.

- 1953 – March 31: Passenger service discontinued on the North Shore Branch and the South Beach Branch train lines.

- 1956 – Staten Island Community College (later College of Staten Island) founded.[57]

- 1958 – Historic Richmond Town (museum) established.

- 1959 – Arthur Kill Vertical Lift Bridge opens to Elizabethport, New Jersey.

- 1960 – December 16: One of the two planes in the 1960 New York mid-air collision crashes into Staten Island.[58]

- 1962 – Archaeology Society of Staten Island founded.[59]

- 1963

- April 20: Rossville Fire.

- Ferry from Tottenville to Perth Amboy discontinued.

- Piels Beer brewery closes.

- 1964

- Verrazano-Narrows Bridge opens to Brooklyn.

- Staten Island Expressway opens.

- Staten Island wins the Little League World Series, defeating the team from Monterrey, Mexico.

- 1965 – Willowbrook Parkway opens.

- 1966 – Staten Island Register newspaper begins publication.[43] Robert T. Connor becomes Borough President. Hylan Plaza shopping centre in business.

- 1970 – Population: 295,443.

- 1971

- July 1: SIRT turned over to division of the MTA.

- St. John's University Staten Island campus opens.

- 1972 – Tottenville High School relocates to a new building in Huguenot.

- 1973 – Staten Island Mall in business.

- 1975 – "Borough of Richmond" becomes "Borough of Staten Island."[60]

- 1976 – Arthur Kill Correctional Facility and College of Staten Island established. Staten Island Children's Museum opens.

- 1977 – Preservation League of Staten Island[61] and Newhouse Center for Contemporary Art founded. Anthony Gaeta becomes Borough President.

- 1978 – Northfield Community Local Development Corp. founded.

- 1979 – Fort Wadsworth transferred to US Navy from US Army.

- 1980 – Population: 352,029.

- 1981 – WSIA radio begins broadcasting.

- 1982 - New Dorp High School relocates to new building south of Hylan Boulevard near Miller Field.

- 1984 – Ralph J. Lamberti becomes Borough President.[62]

- 1988 – Staten Island AIDS Task Force founded.[63]

- 1990

- Naval homeport opens.[64]

- Guy Molinari becomes Borough President.

- 1992 – RZA, GZA, and Ol' Dirty Bastard form the Wu Tang Clan out of the Clifton and Stapleton sections of the Island. Along with Inspectah Deck, Raekwon the Chef, U-God, Ghostface Killah, Method Man, and Masta Killa.

- 1993 – November 2: Voters approve secession of Staten Island from New York City.[65]

- 1994 – Staten Island Conservatory of Music founded.[66] Naval Homeport is closed due to BRAC.

- 1999 – The New York Chinese Scholar's Garden and College of Staten Island Baseball Complex open. Staten Island Yankees baseball team established.

21st century

- 2001 – Richmond County Bank Ballpark opens. Fresh Kills Landfill closes but receives remains and debris from the collapse of the Twin Towers from the September 11 Attacks

- 2002 – James Molinaro becomes Borough President.

- 2004 – Eltingville Transit Center built.

- 2007 – Richmond University Medical Center established.

- 2008 – Staten Island LGBT Community Center opens.[63]

- 2010 – Population: 468,730.

- 2011 – Mosque (Dongan Hills) opens.[67] Arthur Kill Correctional Facility closes.

- 2012 – October: Hurricane Sandy.

- 2014 – Death of Eric Garner.

Geology

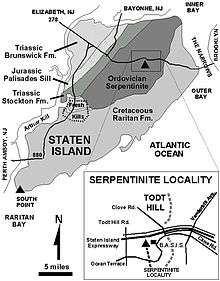

During the Paleozoic Era, the tectonic plate containing the continent of Laurentia and the plate containing the continent of Gondwanaland were converging, the Iapetus Ocean that separated the two continents gradually closed, and the resulting collision between the plates formed the Appalachian Mountains. During the early stages of this mountain building known as the Taconic orogeny, a piece of ocean crust from the Iapetus Ocean broke off and became incorporated into the collision zone and now forms the oldest bedrock strata of Staten Island, the serpentinite.

This strata of the Lower Paleozoic (approximately 430 million years old) consists predominantly of the serpentine minerals, antigorite, chrysotile, and lizardite; it also contains asbestos and talc. At the end of the Paleozoic era (248 million years ago) all major continental masses were joined into the supercontinent of Pangaea.

The Palisades Sill has been designated a National Natural Landmark, being "the best example of a thick diabase sill in the United States." It underlies a portion of northeast Staten Island, with a visible outcropping in Travis, off Travis Road in the William T. Davis Wildlife Refuge. This is the same formation which appears in New Jersey and upstate New York along the Hudson River in Palisades Interstate Park. The sill extends southward beyond the cliffs in Jersey City beneath the Upper New York Harbor and resurfaces on Staten Island. The Palisades sill date from the Early Jurassic period, 192 to 186 million years ago.

Staten Island has been at the southern terminus of various periods of glaciation. The most recent, the Wisconsin Glacier, ended approximately 12,000 years ago. The accumulated rock and sediment deposited at the terminus of the glacier is known as the terminal moraine present along the central portion of the island. The evidence of these glacial periods is visible in the remaining wooded areas of Staten Island in the form of glacial erratics and kettle ponds.[68]

At the retreat of the ice sheet, Staten Island was connected by land to Long Island, as the Narrows had not yet formed. Geologists' reckonings of the course of the Hudson River have placed it alternatively through the present course of the Raritan River, south of the island, or through present-day Flushing Bay and Jamaica Bay.

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, Richmond County has a total area of 102.5 square miles (265 km2), of which 58.5 square miles (152 km2) is land and 44.0 square miles (114 km2) (43%) is water.[69] It is the third-smallest county in New York by land area and fourth-smallest by total area.

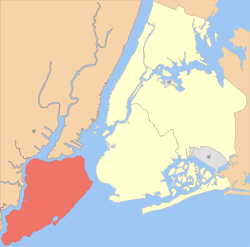

Although Staten Island is officially an administrative borough of New York City and its coterminous Richmond County is an administrative county of New York State, Staten Island is topographically and geologically a part of New Jersey.[70] Staten Island is separated from Long Island by the Narrows and from mainland New Jersey by the Arthur Kill and the Kill Van Kull. Staten Island is positioned at the center of New York Bight, a sharp bend in the shoreline between New Jersey and Long Island. The region is considered vulnerable to sea-level rise.[71] On October 29, 2012, the island experienced severe damage and loss of life along with the destruction of many homes during Hurricane Sandy.[72][73]

In addition to the main island, the borough and county also include several small uninhabited islands:

- The Isle of Meadows (at the mouth of Fresh Kills)

- Prall's Island (in the Arthur Kill)

- Shooters Island (in Newark Bay; part of it belongs to New Jersey)

- Swinburne Island (in Lower New York Bay)

- Hoffman Island (in Lower New York Bay)

The highest point on the island, the summit of Todt Hill, elevation 410 ft (125 m), is also the highest point in the five boroughs, as well as the highest point on the Atlantic Coastal Plain south of Great Blue Hill in Massachusetts and the highest point on the coast proper south of Maine's Camden Hills. Ward's Point in the neighborhood of Tottenville is the southernmost point in the state of New York.

Staten Island is the only borough in New York City that does not share a land border with another borough (Marble Hill in Manhattan is contiguous with the Bronx). The borough has a land border with Elizabeth and Bayonne, New Jersey, on uninhabited Shooters Island.

Wildlife

Staten Island is home to a large and diverse population of wildlife. Wildlife found on Staten Island include white tailed deer (which have increased from a population of 24 in 2008 to 2,000 in 2017 due to a hunting ban and a lack of predators),[74] as well as hundreds of species of birds including bald eagles, turkey, hawks, egrets and ring-necked pheasants. Staten Island is home to horseshoe crabs, cotton tailed rabbits, opossums, raccoons, garter snakes, red-eared slider turtles, newts, spring peeper frogs, leopard frogs, fox, box turtles, northern snapping turtles and common snapping turtles.

Parkland

Staten Island includes thousands of acres of federal, state, and local park land, including the "greenbelt" and "blue belt" park systems and the Gateway National Recreation Area in addition to hundreds of acres of private wooded areas. The National Park Service maintains full-time Wildland Firefighters to patrol the Staten Island sites in wildfire brush trucks.

The parks on Staten Island are managed by various state, federal and local agencies.

Five sites are part of the 26,000-acre (110 km2) Gateway National Recreation Area, managed by the U.S. National Park Service and patrolled by the United States Park Police:

Two New York State parks are managed by the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation:

New York State Park Police officers patrol these parks and the surrounding streets.

359 acres (145 ha) of State Forests, state wildlife management areas and Wetlands are managed by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation:

- Saint Francis Woodland

- Butler Manor Woods

- Arden Heights Woods

- Todt Hill Woods

- North Mount Loretto State Forest

- Lemon creek Tidal Wetland Wildlife Management Area

- Blosers Wetland Wildlife Management Area

- Goethal Pond Wetland

- Bridge Creek Tidal Wetland

- Old Place Creek Tidal Wetland

- Oakwood Beach Wetland

- Sharrots Shoreline Natural Resource Area

- Sawmill Creek Wetland

The 359 acres (145 ha) of NYS Department of Environmental Conservation land throughout the island are patrolled by New York State Department of Environmental Conservation Police officers and one NYS DEC Forest Ranger, who has the dual task of law enforcement and fire suppression.

The New York City Department of Parks and Recreation manages 156 parks, including:

- Conference House Park

- Willowbrook Park

- Graniteville Quarry Park

- Silver Lake Park

- Clove Lake Park

Adjacent counties

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1790 | 3,835 | — | |

| 1800 | 4,564 | 19.0% | |

| 1810 | 5,347 | 17.2% | |

| 1820 | 6,135 | 14.7% | |

| 1830 | 7,082 | 15.4% | |

| 1840 | 10,965 | 54.8% | |

| 1850 | 15,061 | 37.4% | |

| 1860 | 25,492 | 69.3% | |

| 1870 | 33,029 | 29.6% | |

| 1880 | 38,991 | 18.1% | |

| 1890 | 51,713 | 32.6% | |

| 1900 | 67,021 | 29.6% | |

| 1910 | 85,969 | 28.3% | |

| 1920 | 116,531 | 35.6% | |

| 1930 | 158,346 | 35.9% | |

| 1940 | 174,441 | 10.2% | |

| 1950 | 191,555 | 9.8% | |

| 1960 | 221,991 | 15.9% | |

| 1970 | 295,443 | 33.1% | |

| 1980 | 352,029 | 19.2% | |

| 1990 | 378,977 | 7.7% | |

| 2000 | 443,728 | 17.1% | |

| 2010 | 468,730 | 5.6% | |

| Est. 2017 | 479,458 | 2.3% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[75] 1790–1960[76] 1900–1990[77] 1990–2000[78] 2010 and 2017[1] | |||

At the 2010 Census, there were 468,730 people living in Staten Island, which is an increase of 5.6% since the 2000 Census. Staten Island is the only New York City borough with a non-Hispanic White majority. According to the 2010 Census, 64.0% of the population was non-Hispanic White, down from 79% in 1990,[79] 10.6% Black or African American, 0.4% American Indian and Alaska Native, 7.5% Asian, 0.2% from some other race (non-Hispanic) and 2.6% of two or more races. 17.3% of Staten Island's population was of Hispanic or Latino origin (of any race).

In 2009, approximately 20.0% of the population was foreign born, and 1.8% of the populace was born in Puerto Rico, U.S. Island areas, or born abroad to American parents. Concordantly, 78.2% of the population was born in the United States. Approximately 28.6% of the population over five years of age spoke a language other than English at home, and 27.3% of the population over twenty-five years of age had a bachelor's degree or higher.[80]

According to the 2009 American Community Survey, the borough's population was 75.7% White (65.8% non-Hispanic White alone), 10.2% Black or African American (9.6% non-Hispanic Black or African American alone), 0.2% American Indian and Alaska Native, 7.4% Asian, 0.0% Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander, 4.6% from Some other race, and 1.9% from Two or more races. Hispanics or Latinos of any race made up 15.9% of the population.[81]

According to the survey, the top ten European ancestries were the following:

- Italian: 33.7%

- Irish: 14.2%

- German: 5.7%

- Russian: 3.8%

- Polish: 3.4%

- English: 1.6%

- Ukrainian: 1.3%

- Norwegian: 1.0%

- Greek: 1.0%

- French: 0.9%

The borough has the highest proportion of Italian Americans of any county in the United States. Since the 2000 census, a large Russian community has been growing on Staten Island, particularly in the Rossville, South Beach, and Great Kills area. There is also a significant Polish community mainly in the South Beach and Midland Beach area and there is also a large Sri Lankan community on Staten Island, concentrated mainly on Victory Boulevard on the northeastern tip of Staten Island towards St. George. The Little Sri Lanka in the Tompkinsville neighborhood is one of the largest Sri Lankan communities outside of the country of Sri Lanka.[82][83] The borough is also home to a Chinanteco-speaking Mexican American community.[84]

The vast majority of the borough's African American and Hispanic residents live north of the Staten Island Expressway, or Interstate 278. In terms of religion, the population is largely Roman Catholic. There is a growing presence of Egyptian Copts, the vast majority of whom are members of the Coptic Orthodox Church.[85]

Per the 2009 American Community Survey, the median income for a household was $55,039, and the median income for a family was $64,333. Males had a median income of $50,081 versus $35,914 for females. The per capita income for the borough was $23,905. About 7.9% of families and 10.0% of the population were below the poverty line, including 13.2% of those under age 18 and 9.9% of those age 65 or over.

Languages

As of 2010, 70.39% (306,310) of Staten Island residents age 5 and older spoke English at home as a primary language, while 10.02% (43,587) spoke Spanish, 3.14% (13,665) Russian, 3.11% (13,542) Italian, 2.39% (10,412) Chinese, 1.81% (7,867) other Indo-European languages, 1.38% (5,990) Arabic, 1.01% (4,390) Polish, 0.88% (3,812) Korean, 0.80% (3,500) Tagalog, 0.76% (3,308) other Asian languages, 0.62% (2,717) Urdu, 0.57% (2,479) other Indic languages, and African languages were spoken as a main language by 0.56% (2,458) of the population over the age of five. In total, 29.61% (128,827) of Staten Island's population age 5 and older spoke a mother language other than English.[86]

Government and politics

History

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third Parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 56.1% 101,437 | 41.0% 74,143 | 3.0% 5,380 |

| 2012 | 48.1% 74,223 | 50.7% 78,181 | 1.2% 1,776 |

| 2008 | 51.7% 86,062 | 47.6% 79,311 | 0.7% 1,205 |

| 2004 | 56.4% 90,325 | 42.7% 68,448 | 0.9% 1,370 |

| 2000 | 45.0% 63,903 | 51.9% 73,828 | 3.1% 4,398 |

| 1996 | 40.8% 52,207 | 50.5% 64,684 | 8.7% 11,116 |

| 1992 | 47.9% 70,707 | 38.5% 56,901 | 13.6% 20,152 |

| 1988 | 61.5% 77,427 | 38.0% 47,812 | 0.6% 736 |

| 1984 | 65.1% 83,187 | 34.7% 44,345 | 0.2% 294 |

| 1980 | 58.6% 64,885 | 33.7% 37,306 | 7.7% 8,456 |

| 1976 | 54.1% 56,995 | 45.5% 47,867 | 0.4% 464 |

| 1972 | 74.2% 84,686 | 25.6% 29,241 | 0.2% 196 |

| 1968 | 55.3% 54,631 | 35.2% 34,770 | 9.5% 9,423 |

| 1964 | 45.5% 42,330 | 54.4% 50,524 | 0.1% 92 |

| 1960 | 56.5% 50,356 | 43.4% 38,673 | 0.1% 94 |

| 1956 | 76.6% 64,233 | 23.4% 19,644 | 0.0% 0 |

| 1952 | 66.2% 55,993 | 33.4% 28,280 | 0.4% 294 |

| 1948 | 54.1% 39,539 | 41.6% 30,442 | 4.3% 3,153 |

| 1944 | 57.1% 42,188 | 42.6% 31,502 | 0.3% 228 |

| 1940 | 50.2% 38,911 | 49.5% 38,307 | 0.3% 249 |

| 1936 | 32.5% 22,852 | 65.7% 46,229 | 1.9% 1,308 |

| 1932 | 35.3% 21,278 | 61.1% 36,857 | 3.7% 2,210 |

| 1928 | 46.1% 24,995 | 53.4% 28,945 | 0.5% 294 |

| 1924 | 47.9% 18,007 | 42.0% 15,801 | 10.1% 3,778 |

| 1920 | 63.2% 17,844 | 33.2% 9,373 | 3.7% 1,041 |

| 1916 | 44.4% 7,319 | 53.6% 8,843 | 2.0% 336 |

| 1912 | 19.3% 3,035 | 53.6% 8,445 | 27.1% 4,277 |

| 1908 | 45.3% 6,831 | 49.1% 7,401 | 5.7% 852 |

| 1904 | 47.7% 7,000 | 49.0% 7,182 | 3.3% 486 |

| 1900 | 45.8% 6,042 | 51.2% 6,759 | 3.0% 400 |

| 1896 | 55.1% 6,170 | 39.8% 4,452 | 5.1% 576 |

| 1892 | 38.1% 4,091 | 57.0% 6,122 | 4.9% 528 |

| 1888 | 40.8% 4,100 | 57.4% 5,764 | 1.8% 179 |

| 1884 | 37.4% 3,164 | 60.7% 5,135 | 1.9% 164 |

Since New York City's consolidation in 1898, Staten Island has been governed by the New York City Charter that provides for a "strong" mayor-council system. The centralized New York City government is responsible for public education, correctional institutions, libraries, public safety, recreational facilities, sanitation, water supply, and welfare services on Staten Island.

The office of Borough President was created in the consolidation of 1898 to balance centralization with local authority. Each borough president had a powerful administrative role derived from having a vote on the New York City Board of Estimate, which was responsible for creating and approving the city's budget and proposals for land use.

The Office of Borough President became one focal point for opinions over the Vietnam War when former intelligence agent and peace activist Ed Murphy ran for office in 1973, sponsored by the Staten Island Democratic Association. Murphy's combat veteran status deflected traditional right-wing attacks on liberals, and the campaign facilitated the emergence of more liberal politics on Staten Island. In 1989 the Supreme Court of the United States declared the Board of Estimate unconstitutional on the grounds that Brooklyn, the most populous borough, had no greater effective representation on the board than Staten Island, the least populous borough, a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment's Equal Protection Clause pursuant to the high court's 1964 "one man, one vote" decision.[88]

Since 1990 the Borough President has acted as an advocate for the borough at the mayoral agencies, the City Council, the New York state government, and corporations. Staten Island's Borough President is James Oddo, a Republican elected in November 2013 with 69.1% of the vote. Oddo is the only Republican borough president in New York City.

Staten Island flag

The flag is on a white background in the center of which is the design of a seal in the shape of an oval. Within the seal appears the color blue to symbolize the skyline of the borough, in which two seagulls appear colored in black and white. The green outline represents the countryside of the borough with white outline denoting the residential areas of Staten Island. Below is inscribed the words "Staten Island" in gold. Below this are five wavy lines of blue to symbolize the water that surrounds the island borough on all sides. Gold fringe outlines the flag.[89]

Politics

Staten Island's politics differ considerably from those of New York City's other boroughs. Although in 2005 44.7% of the borough's registered voters were registered Democrats and 30.6% were registered Republicans, the Republican Party holds a small majority of local public offices. Staten Island is the base of New York City's Republican Party in citywide elections.

In the 2001 mayoral election, borough voters chose Republican Michael Bloomberg, with 75.87% of the vote, over Democrat Mark Green, with 21.15% of the vote. Since Green narrowly lost the election citywide, Staten Island provided the margin of Bloomberg's victory.

The main political divide in the borough is demarcated by the Staten Island Expressway; areas north of the Expressway tend to be more liberal while the south tends to be more conservative. Local party platforms center on affordable housing, education and law and order. Two out of Staten Island's three New York City Council members are Republicans, including conservative commentator Joe Borelli.

In national elections, Staten Island is a Republican-leaning swing county. Staten Island has voted for a Democratic presidential nominee only four times since 1952: in 1964, 1996, 2000, and 2012. In the 2004 presidential election, Republican George W. Bush received 56% of the vote in Staten Island, and Democrat John Kerry received 43%. By contrast, Kerry outpolled Bush in New York City's other four boroughs by a cumulative margin of 77% to 22%. In the 2008 presidential election, Republican John McCain won 52% of the vote in the borough to Democrat Barack Obama's 48%. In 2012, the borough flipped and was won by incumbent Democrat Barack Obama, who took 51% of the vote to Republican Mitt Romney's 48%. This made it the fourth time since 1952 that Democrats have carried Staten Island, and made the borough one of the few parts of the country where Barack Obama gained an advantage compared to 2008.[90] In 2016, Republican Donald Trump carried Staten Island by 15.1%, the largest margin of any presidential candidate since 1988. He became the first ever presidential candidate to receive 100,000 votes out of Staten Island. Each of the city's five counties (coterminous with each borough) has its own criminal court system and District Attorney, the chief public prosecutor who is directly elected by popular vote. Michael McMahon, a Democrat, is the current District Attorney.[91] Staten Island has three City Council members, two Republicans and one Democrat, the smallest number among the five boroughs.

It also has three administrative districts, each served by a local Community Board. Community Boards are representative bodies that field complaints and serve as advocates for local residents. In the 2009 election for city offices, Staten Island elected its first black official, Debi Rose, who defeated the incumbent Democrat in the North Shore city council seat in a primary and then went on to win the general election.

Staten Island lies entirely within New York's 11th congressional district, which also includes part of southwestern Brooklyn. It is represented by Daniel Donovan, who was elected in a special election on May 5, 2015, to replace Michael Grimm, who had resigned earlier in the year after pleading guilty to tax fraud.[92][93]

| Party | 2005 | 2004 | 2003 | 2002 | 2001 | 2000 | 1999 | 1998 | 1997 | 1996 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic (%) | 44.70 | 44.76 | 45.19 | 45.39 | 45.63 | 45.47 | 45.51 | 45.60 | 46.38 | 46.15 |

| Republican (%) | 30.64 | 30.47 | 30.77 | 30.55 | 30.68 | 30.76 | 31.17 | 31.60 | 30.80 | 31.28 |

| No affiliation (%) | 19.00 | 19.10 | 18.46 | 18.54 | 18.67 | 18.84 | 18.67 | 18.25 | 18.43 | 18.48 |

| Other (%) | 5.66 | 5.67 | 5.58 | 5.52 | 5.02 | 4.93 | 4.65 | 4.55 | 4.39 | 4.09 |

Local politics

Staten Island representation in the state assembly has two Democrats and two Republicans. The 60th district[94] is represented by Republican Nicole Malliotakis, and the 62nd,[95] which encompasses most of the south shore of the island, by Joseph Borelli. But both the 61st[96] and 63rd[97] districts have elected Democrats, Matthew Titone and Michael J. Cusick. Staten Island is split between two State Senate Districts. Most of the island used to be represented by Republican John J. Marchi,[98] the longest-serving legislator in state history; but is now represented by Republican Andrew Lanza; while the North Shore belongs to the Brooklyn-based district of Democrat Diane Savino.[99]

In New York City mayoral elections, Staten Island has traditionally been reliably Republican, having voted for the Republican mayoral nominee in every election since 1989, having last voted Democratic for incumbent Mayor Ed Koch in 1985. Staten Island's high Republican turnout is considered one of the major factors that helped Rudy Giuliani win in 1993 against incumbent Democratic Mayor David Dinkins.

Tourism

In 2009, Borough President James Molinaro started a program to increase tourism on Staten Island. At the top of that program was a new website, visitstatenisland.com. The tourism program also includes a "Staten Island Attractions" video that is aired in both the Staten Island and the Manhattan Whitehall ferry terminals, as well as informational kiosks at the terminals, which supply printed information on Staten Island attractions, entertainment and restaurants.

Empire Outlets New York City, also known as Harbor Commons, is a 350,000-square-foot (33,000 m2) retail complex being constructed in the St. George neighborhood of Staten Island, New York City. Empire Outlets will feature 100 designer outlets and a 120,000 sq ft (11,000 m2) hotel upon its completion in late 2018. It will be the first outlet mall in New York City. The mall is located next to the St. George Terminal, a major ferry, train, and bus hub.

Staten Island is known as the borough of parks because of its numerous parks. Some well known parks are Clove Lakes, Silver Lake, Greenbelt and High Rock. A great sight to see gorgeous points of Staten Island is Moses Mountain, which is a hill where Robert Moses wanted to build a highway through but protests defeated this arrangement. It is now a key point of Staten Island for tourists.

Culture

Local support for the arts

Artists and musicians have been moving to Staten Island's North Shore so they can be in close proximity to Manhattan but also have enough affordable space to live and work.[5][100][101] Filmmakers, most of whom work independently, also play an important part in Staten Island's art scene, which has been recognized by the local government. Staten Island Arts (formerly The Council on the Arts and Humanities for Staten Island) is Staten Island's local arts council and helps support local artists and cultural organizations with regrants, workshops, folklife and arts-in-education programs, and advocacy.[102] Conceived by the Staten Island Economic Development Corporation to introduce independent and international films to a broad and diverse audience, the Staten Island Film Festival (SIFF) held its first four-day festival in 2006.

Attractions

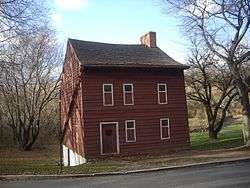

Historic Richmond Town is New York City's living history village and museum complex. Visitors can explore the diversity of the American experience, especially that of Staten Island and its neighboring communities, from the colonial period to the present. The village area occupies 25 acres (100,000 m2) of a 100-acre (0.40 km2) site with about 15 restored buildings, including homes, commercial and civic buildings, and a museum.

The island is home to the Staten Island Zoo. Zoo construction commenced in 1933 as part of the Federal Government's works program on an eight-acre (three-hectare) estate willed to New York City. It was opened on June 10, 1936, the first zoo in the U.S. specifically devoted to an educational mandate. In the late 1960s, the zoo maintained the most complete rattlesnake collection in the world with 39 varieties.

Museums

Snug Harbor Cultural Center, the Alice Austen House Museum, the Conference House, the Garibaldi–Meucci Museum, Historic Richmond Town, Jacques Marchais Museum of Tibetan Art, the Noble Maritime Collection, Sandy Ground Historical Museum,[103] Staten Island Children's Museum, the Staten Island Museum and the Staten Island Botanical Garden, home of The New York Chinese Scholar's Garden can all be found on the island.

The National Lighthouse Museum recently undertook a major fundraising project and opened in 2012, and the Staten Island Museum (art, science, and history) plans to open a new branch in Snug Harbor by 2014.

The Seguine Mansion, also known as The Seguine-Burke Mansion, is located on Lemon Creek near the southern shore of Staten Island. The Greek Revival house is one of the few surviving examples of 19th century life on Staten Island. It is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and is a member of the Historic House Trust. It is an underappreciated attraction, harboring 18 peacocks[104] and an equestrial center.

Newspapers

Staten Island's local paper is The Staten Island Advance. The paper also has an affiliated website called silive.com.

In culture

Film

Movies filmed partially or wholly on Staten Island include:

Literature

Ki Longfellow was born on the island. Longfellow is the author of The Secret Magdalene and other books. Her Sam Russo historical detective noir novels are based in and around Stapleton.

Lois Lowry, the author of The Gossamer and many other books, attended school on Staten Island.

Writer Paul Zindel lived in Staten Island during his youth and based most of his teenage novels in the island.

George R.R. Martin based King's Landing on the view of Staten Island from his childhood home in Bayonne, New Jersey.[105]

Music

Staten Island also has a local music scene. Most shows are at The Full Cup or the old Dock Street in Stapleton. These venues in the North Shore are part of the art movement mentioned above. Local bands include many punk, ska, hardcore punk, indie, metal, and pop punk bands.

Musicians who were born or reside on Staten Island and groups that formed on Staten Island are found at List of people from Staten Island.

Television

- Time Warner Cable's news channel NY1 airs a weekly show called This Week on Staten Island, hosted by Anthony Pascale. The magazine style show takes content from NY1's daily/hourly newscasts called "Your Staten Island News Now".

- The documentary, A Walk Around Staten Island with David Hartman and Barry Lewis, premiered on public television station WNET on December 3, 2007, profiling Staten Island culture and history, including major attractions such as the Staten Island Ferry, Historic Richmondtown, the Conference House, Snug Harbor Cultural Center, the Chinese Scholars Garden and many more sites.[106]

- A Fox and WB sitcom called Grounded For Life aired from 2001-2005 and was centered around a family of Irish heritage living on Staten Island.[107]

Theater

The St. George Theatre serves as a cultural arts center, hosting educational programs, architectural tours, television and film shoots, concerts, comedy, Broadway touring companies, and small and large children's shows. Artists who have performed there include The B-52s, The Jonas Brothers, Tony Bennett, and Don McLean. In 2012, the NBC musical drama Smash filmed several scenes there.[108]

Sports

- Tennis is said to have made its debut in the United States of America on Staten Island in New York State. The first American National championship was played there in September 1880. Tennis was introduced in Staten Island by Mary Ewing Outerbridge.[109]

- Staten Island Yankees, New York–Penn League baseball, Class A Minor League affiliate to the New York Yankees

- The New York Cosmos u23, part of the USL Premier Development League (PDL), call Staten Island home. The team plays at Monsignor Farrell High School and is affiliated with the New York Cosmos.

- The New York Metropolitans of the American Association played baseball on Staten Island from April 1886 through 1887. Erastus Wiman, the developer of St. George, brought the team to Staten Island where they played in a stadium called the St. George Grounds, near the site of the current-day Staten Island Yankees' Richmond County Bank Ballpark and the Staten Island Ferry terminal.

- Wagner College participates in Division I athletics.

- NBA basketball coach P.J. Carlesimo coached the Wagner College Basketball team the "Seahawks".

- Staten Island formerly had a National Football League team, the Stapletons. Based in Stapleton. Their stadium, Thompson Stadium, was located on the site of Berta A. Dreyfus Intermediate School 49 and the Stapleton Houses. They played in the league from 1929 to 1932, defeating the New York Giants twice and the Chicago Cardinals once. During the 1932 NFL season the Stapletons, last in the NFL, played the eventual season champion Chicago Bears to a scoreless tie. Football Hall of Famer Ken Strong played for the Stapletons.

- The New York Predators of the semi-pro Regional American Football League have called Staten Island home since their inception in 1998. Owned by Bill Simo, they play most home games at St. Peters H.S.[110]

- There was a controversial plan by the International Speedway Corporation to build a speedway on the island that would host NASCAR races by 2010. ISC abandoned the plan in 2006, citing financial concerns.

- In 1964 Staten Island's Mid Island Little League won the Little League World Series in Williamsport, Pennsylvania.

- The Staten Island Cricket Club, incorporated in 1866,[111] is the oldest continuously operating cricket club in the United States.[112]

Education

Public schools

Public schools in the borough are managed by the New York City Department of Education, the largest public school system in the United States.

Public middle schools include Intermediate Schools 2, 7, 14, 16, 21, 24, 27, 32, 34, 35, 42, 46, 48, 49, 51, 61, 63, 72 and 75, and 861, a K to 8 school as well as part of the Petrides School (which runs from kindergarten to high school)

Public high schools include:

- College of Staten Island High School for International Studies

- Curtis High School

- Gaynor McCown Expeditionary Learning School

- New Dorp High School

- Petrides High School

- Port Richmond High School

- Staten Island Technical High School

- Susan E. Wagner High School

- Tottenville High School

- Ralph R. McKee CTE High School

Private schools

- Staten Island Academy is the only independent private (non-public, non-religious) grade school on the island and is one of the oldest in the entire country.

- Gateway Academy (co-educational)

- St. John Villa Academy (all-girls)

- St. Peter's Boys High School (all-boys)

- St. Peter's High School for Girls (all-girls)

- Notre Dame Academy (New York) (all-girls)

- St. Joseph Hill Academy (all-girls)

- Monsignor Farrell High School (all-boys)

- Moore Catholic High School (co-educational)

- St. Joseph by the Sea High School (co-educational)

Moore Catholic and St. Joseph by the Sea are the only co-educational Catholic high schools on the island.

- Miraj Islamic School (co-educational)

Colleges and universities

- The College of Staten Island is one of the eleven senior colleges of the City University of New York (CUNY). The college offers both associate's and bachelor's degrees. The College of Staten Island also offers post-graduate level study from master's to doctoral level study.

- Wagner College is a coeducational private liberal arts college with an enrollment of 2,000 undergraduates and 500 graduate students.

- St. John's University has a campus on Staten Island. It is a private, coeducational Roman Catholic university.

Transportation

Staten Island is connected to New Jersey via three vehicular bridges and one railroad bridge. The Outerbridge Crossing to Perth Amboy, New Jersey, is at the southern end of Route 440, and the Bayonne Bridge to Bayonne, New Jersey, is at the northern end of Route 440, which continues into Jersey City, New Jersey. From the New Jersey Turnpike, the Goethals Bridge using I-278 connects from Elizabeth, New Jersey, to the Staten Island Expressway. The Arthur Kill Vertical Lift Railroad Bridge carries freight between the northwest part of the island and Elizabeth, New Jersey. Staten Island is connected to Brooklyn via the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge using the Staten Island Expressway. The only pedestrian link to Staten Island is via a footpath on the Bayonne Bridge.

Unlike the other four boroughs, Staten Island has no large, numbered grid system. New Dorp's grid has a few numbered streets, but they do not intersect with any numbered avenues. Some neighborhoods, however, organize their street names alphabetically.

Staten Island was, at one point, concurrently home to the longest vertical lift bridge, steel arch bridge, and suspension bridge in the world; the Arthur Kill Vertical Lift Bridge, Bayonne Bridge, and Verrazano-Narrows Bridge, respectively. The Arthur Kill Bridge still holds the title for longest vertical lift bridge, while the Bayonne and Verrazano bridges are now the 4th and 8th longest, in their respective categories.

Staten Island has more cars per capita than any other borough in New York City, with car ownership attained by 81.6% of all Staten Island households. Citywide, the car ownership rate is 45%.[113]

Public transport

Public transportation on the island is limited to:

- New York City Department of Transportation (Staten Island Ferry)

- MTA Regional Bus Operations (local service on Staten Island and express service to Manhattan)

- Staten Island Railway service from St. George to Tottenville

Ferry

The Staten Island Ferry is the only direct transportation network from Staten Island to Manhattan, roughly a 25-minute trip.[114] The St. George ferry terminal, built in 1950, recently underwent a $130-million renovation and now features floor-to-ceiling glass for panoramic views of the harbor and incoming ferries. The ferry had its fare eliminated in 1997. The Staten Island Ferry had undergone ramp renovations which were completed in 2014. The Staten Island Ferry transports over 60,000 passengers per day. The ferry makes the 25 minute trip across New York Harbor 109 times every weekday, 24 hours every day, while utilizing five boats, and 75 times on Saturdays and 68 times every Sunday, using a three boat fleet. NYS Department of Transportation Peace Officers in conjunction with the New York City Police Department and U.S Coast Guard patrol the ferry terminal.

Trains

The Staten Island Railway traverses the island from its northeastern tip to its southwestern tip. The Staten Island Railway opened in 1860[115][116][117] and was owned and operated by the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) until July 1, 1971, when the line was bought by the Metropolitan Transportation Authority.[118] The Staten Island Railway continued to have its own railway police, the Staten Island Rapid Transit Police, until 2005 when the 25 officer police force was consolidated into the Metropolitan Transportation Authority Police. MTA Police officers patrol the island's only passenger railway. Staten Island is the only borough not served by the New York City Subway, as the Staten Island Tunnel was abandoned in the middle of construction in the 1920s. It lies dormant beneath Owl's Head Park in Brooklyn. As such, express bus service is provided by NYC Transit throughout Staten Island to Lower and Midtown Manhattan.

A five-mile right of way exists along the north shore of Staten Island. The rail line was built, owned, and operated by the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, which used the line for passenger service until 1953. It then became a Baltimore and Ohio Railroad freight line until the 1980s, when freight service was stopped. There have been proposals to revive the abandoned North Shore Branch of the Staten Island Railway for passenger service as a rail line or for use as bus rapid transit.[119] There is also a proposal to build a West Shore Light Rail in the center of the Dr. Martin Luther King Expressway, Staten Island Expressway, and West Shore Expressway, continuing to Richmond Valley, Staten Island, to connect with the main line of the Staten Island Railway. The South Beach Branch, which transported summer vacationers to South Beach, Staten Island, ceased service in 1953.[120]

Buses

MTA Regional Bus Operations provides local and limited bus service with over 30 lines throughout Staten Island. Most lines feed into the St. George Ferry Terminal in the northeastern corner of the borough. Three lines (the S53, S93 and S79 SBS) provide service over the Verrazano Bridge to Bay Ridge, Brooklyn. The S79 SBS is the only Select Bus Service route in the borough. Beginning September 4, 2007, the MTA began offering bus service from Staten Island to Bayonne, New Jersey, over the Bayonne Bridge via the S89 limited-stop bus, allowing passengers to connect to the Hudson-Bergen Light Rail's 34th Street station, giving Staten Island residents a new route into Manhattan. Despite Staten Island's proximity to New Jersey, the S89 is the only route directly into New Jersey from Staten Island via public transportation.[121]

Express bus service to Manhattan via the Verrazano Bridge and the Gowanus Expressway is also available for a $6.50 fare each way. The SIM1C, SIM2, SIM3C and SIM4C are the only ones to run outside of rush hour.[122]

Freight rail

Conrail Shared Assets Operations operates freight rail service for customers of CSX Transportation and the Norfolk Southern Railway via the Travis Branch with a 38 acres (15 ha) intermodal on-dock rail facility on the southern end of Staten Island which connects to the National Rail System via the Arthur Kill Rail Bridge to New Jersey. In addition to the intermodal on-dock rail yard, the Conrail Staten Island Rail line also connects to the Sanitation departments waste transfer station. Conrail railroad police officers patrol and respond to emergencies along the freight line.

Infrastructure

Hospitals

Staten Island is the only borough without a hospital operated by New York City. The Richmond University Medical Center and the Staten Island University Hospital are privately operated.

Jails

Staten Island is the only borough without a New York City Department of Corrections major detention center. The Department of Corrections only maintains court holding jails at the three court buildings on Staten Island for inmates attending court. The various police agencies on Staten Island maintain in-house holding jails for post arrest detention prior to transfer to a corrections jail in another borough.

The Staten Island county sheriff operated a jail system on Staten Island until 1942, when the Staten Island jail system was transferred from the county sheriff's department to the New York City Department of Corrections and eventually closed. In 1976, the New York State Department of Correctional Services opened the Arthur Kill Correctional Facility of Staten Island, but the facility was closed in 2011.

Nicknames

Staten Island has acquired a number of nicknames over the decades, some connected to the notion that it is considered an afterthought by other New York City residents. The "Forgotten Borough" was first used nearly 100 years ago in a New York Times article which quoted a real estate executive. The phrase was more used during the secession movement of the 1990s, and came into greater use in the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy.[123] The hip-hop group Wu-Tang Clan coined the nickname "Shaolin Land" (later simply Shaolin) as part of their slang. Most recently people have been using "The Rock", more commonly associated with Alcatraz, as a nickname which first appeared in a New York Times article in 2007.[124]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 "State and County QuickFacts – Richmond County (Staten Island Borough), New York". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 31, 2018.

- ↑ "Conference House Park". New York City Parks. Retrieved June 21, 2014.

- ↑ "Timeline of Staten Island – 1900s – Present". New York Public Library. Archived from the original on January 13, 2006. Retrieved January 16, 2006.

Well over 75% of south shore residents report Italian ancestry, due in large part of residents moving from heavily populated Italian-American neighborhoods such as Bensonhurst (little Italy) Brooklyn to Staten Island.

- ↑ Brown, Chip (January 30, 1994). "Escape From New York". The New York Times. Retrieved January 14, 2008.

Given their status as residents of "the forgotten borough" – the sorry Cinderella sister in New York's dysfunctional family – maybe the giddiest aspect of all was the attention.

- 1 2 Buckley, Cara (October 7, 2007). "Bohemia by the Bay". The New York Times. Retrieved January 14, 2008.

Even as New York's hip young things invade and colonize neighborhoods near, far and out of state, Staten Island has stayed stubbornly uncool. It remains the forgotten borough.

- ↑ "South Beach & FDR Boardwalk of Staten Island, NYC". Si-web.com. Retrieved January 11, 2012.

- ↑ "Fresh Kills Landfill". Freshkills Park Blog. Retrieved January 11, 2012.

- ↑ History: Staten Island, US Army Corps of Engineers Archived September 14, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Fresh Kills Park". Retrieved November 4, 2011.

- ↑ "Current Population Estimates: NYC". NYC.gov. Retrieved June 10, 2017.

- ↑ QuickFacts New York city, New York; Bronx County (Bronx Borough), New York; Kings County (Brooklyn Borough), New York; New York County (Manhattan Borough), New York; Queens County (Queens Borough), New York; Richmond County (Staten Island Borough), New York, United States Census Bureau. Accessed June 11, 2018.

- 1 2 Jackson, 1995

- ↑ Ritchie, 1963

- ↑ Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History, Volumes 3–4 By American Museum of Natural History

- ↑ Bayles, Richard Mather (1887). History of Richmond County (Staten Island), New York.

- ↑ Russell Shorto, The Island at the Center of the World: The Epic Story of Dutch Manhattan and the Forgotten Colony that Shaped America. First Edition. New York City: Vintage Books (a Division of Random House, 2004), ISBN 1-4000-7867-9

- ↑ Ellis, Edward Robb (1966). The Epic of New York City. Old Town Books. p. 55.

- ↑ Memories: Staten Island might well have been called Huguenot Island Accessed February 11, 2018

- ↑ Scheltema, Gajus and Westerhuijs, Heleen (eds.), Exploring Historic Dutch New York. Museum of the City of New York/Dover Publications, New York (2011) ISBN 978-0-486-48637-6

- ↑ Morris pgs.188-189

- ↑ Chan, Sewell (February 21, 2007). "That Old Tale About S.I.? Hold On Now". New York Times.

- 1 2 Greene and Harrington (1932). American Population Before the Federal Census of 1790. New York. , as cited in: Rosenwaike, Ira (1972). Population History of New York City. Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press. p. 12. ISBN 0-8156-2155-8.

- ↑ Morris, Ira. Morris's Memorial History of Staten Island, New York, Volume 1. 1898, page 40

- ↑ McFadden, Robert D. (March 5, 1994). "'Home Rule' Factor May Block S.I. Secession". The New York Times. Retrieved October 20, 2009.

- ↑ John, Lloyd; Mitchinson, John (October 5, 2006). QI: The Book of General Ignorance. Faber and Faber. pp. 114–115. ISBN 0-571-23368-6.

- ↑ "Fresh Kills:Landfill to Landscape". Archived from the original on June 3, 2007 – via archive.org.

- ↑ "Fresh Kills". New York City Department of City Planning. 2009. Archived from the original on November 24, 2009. Retrieved October 20, 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Arthur Fremont Rider (1916), "Staten Island", Rider's New York City and Vicinity, New York: H. Holt and Company

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Staten Island", Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.), New York, 1910, OCLC 14782424

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Franklin B. Hough (1872), "Richmond County", Gazetteer of the State of New York, Albany, N.Y: Andrew Boyd, OCLC 18450990

- ↑ Morris, Page 179.

- 1 2 3 "Staten Island Church Records", Collections of the New York Genealogical and Biographical Society, NY, 4, 1909

- ↑ "Pokémon Go players trespass in Staten Island's Moravian Cemetery".

- ↑ Hartman, Barry. "An Island Within a Cty". A Walk Around Staten Island. WNET 13. Retrieved September 23, 2013.

- ↑ A.Y. Hubbell (1898), History of Methodism and the Methodist Churches of Staten Island, New York: Richmond Pub. Co.

- ↑ Jedidiah Morse; Richard C. Morse (1823), "Richmond County", A New Universal Gazetteer (4th ed.), New Haven: S. Converse

- 1 2 3 Richard Mather Bayles (1887), History of Richmond County (Staten Island), New York from its discovery to the present time, New York: L.E. Preston

- ↑ Ira K. Morris (1898), Morris's Memorial History of Staten Island, New York, New York: Memorial Pub. Co. v.1, v.2 (1900)

- ↑ "Pavilion, New Brighton", The Plain Dealer, NY, July 15, 1837, OCLC 11777382

- ↑ "Staten Island Rich in Little Known Historical Landmarks", The New York Times, July 13, 1913

- ↑ Davies Project. "American Libraries before 1876". Princeton University. Retrieved August 10, 2013.

- ↑ McMillen, Loring (1942). "How We Study Local History on Staten Island". New York History. 23. JSTOR 23135244.

- 1 2 "US Newspaper Directory". Chronicling America. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress. Retrieved August 10, 2013.

- ↑ George Ripley; Charles A. Dana, eds. (1879). "Staten Island". The American Cyclopaedia (2nd ed.). New York: D. Appleton and Company.

- ↑ Morris, pgs 472-3. It was later acquired by {{Piels Beer]] and operated until 1963, making it the longest operated brewery.

- ↑ Sciences, Staten Island Institute of Arts and (1906). Staten Island Institute of Arts and Sciences ... History, Act of Incorporation, Constitution and By-laws.

- ↑ Proceedings of the Bi-Centennial Celebration of Richmond County, Staten Island, New York, New York, 1883

- 1 2 3 "Mapping Staten Island". Museum of the City of New York. 2012. Archived from the original on October 9, 2015.

- ↑ "Richmond Country Country Club Story". Staten Island: Richmond Country Country Club. Archived from the original on August 12, 2012. Retrieved August 10, 2013.

- ↑ American Art Annual, 17, NY: American Federation of Arts, 1920

- ↑ July 10, 2014. Accessed February 11, 2018

- ↑ "On Staten Island, the Fight to Save a Proud Past", The New York Times, September 19, 2009

- ↑ Kenneth M Gold; Lori Robin Weintrob (2011). Discovering Staten Island: a 350th anniversary commemorative history. Charleston, South Carolina: History Press. ISBN 9781609491703.

- ↑ Bayonne Bridge over the Kill van Kull between Port Richmond, Staten Island, New York and Bayonne, New Jersey. Dedication November 14th, 1931

- ↑ "U.S. Foreign-Trade Zones Board Order Summary". Washington DC: U.S. Department of Commerce, International Trade Administration. Retrieved September 16, 2016.

- ↑ "Movie Theaters in New York". Los Angeles: Cinema Treasures. Retrieved August 10, 2013.

- ↑ Accessed February 8, 2018

- ↑ http://cityroom.blogs.nytimes.com/tag/park-slope-plane-crash/

- ↑ "New York City: Staten Island On The Web". New York Public Library. Retrieved August 10, 2013.

- ↑ Jeffrey A. Kroessler (2002), New York year by year: a chronology of the great metropolis, New York: New York University Press, ISBN 0814747515

- ↑ "Preservation League of Staten Island". Archived from the original on September 23, 2011. Retrieved August 10, 2013.

- ↑ "New S.I. Borough President is Sworn In", The New York Times, November 11, 1984

- 1 2 "Staten Island Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, & Transgender History". Staten Island LGBT Community Center. Archived from the original on June 2, 2013. Retrieved August 10, 2013.

- ↑ "A Final Staten Island Homecoming". The New York Times. February 6, 1994. Retrieved August 10, 2013.

- ↑ "Staten Island: Secession Is Approved; Next Move Is Albany's". The New York Times. November 3, 1993.

- ↑ "About Us". Staten Island Conservatory of Music. Archived from the original on June 1, 2013. Retrieved August 10, 2013.

- ↑ "Mosque Opens Quietly on Staten Island", The New York Times, August 18, 2011

- ↑ Isachsen, Yngvar W. "Continental Collisions and Ancient Volcanoes: The Geology of Southeastern New York", Educational Leaflet No. 24, The New York State Educational Department.

- ↑ "2010 Census Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. August 22, 2012. Archived from the original on May 19, 2014. Retrieved January 7, 2015.

- ↑ Snyder, John P. (June 1968). The Story of New Jersey's Civil Boundaries 1606 – 1968 (PDF) (1st ed.). Trenton, New Jersey: New Jersey Bureau of Geology and Topography. p. 14. Retrieved April 11, 2016.

- ↑ "U.S. Geological Survey Studies in the New York Bight". Woods Hole Science Center, U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved November 8, 2012.

- ↑ "Why Hurricane Sandy Hit Staten Island So Hard". AccuWeather, Inc. Retrieved November 8, 2012.

- ↑ Paulsen, Ken. "Staten Island Hurricane Sandy overview: Thursday evening". Staten Island Advance. Retrieved November 8, 2012.

- ↑ Wolfe, Jonathan (2017-09-22). "Solving Staten Island's Deer Problem With a Snip and a Stitch". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-09-23.

- ↑ "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 7, 2015.

- ↑ "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved January 7, 2015.

- ↑ "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 7, 2015.

- ↑ "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 7, 2015.

- ↑ "New York – Race and Hispanic Origin for Selected Cities and Other Places: Earliest Census to 1990". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on August 6, 2012. Retrieved May 6, 2012.

- ↑ Bureau, U.S. Census. "American FactFinder - Search". factfinder.census.gov.

- ↑ Bureau, U.S. Census. "American FactFinder - Results". factfinder.census.gov.