Coney Island

| Coney Island | |

|---|---|

| Neighborhood of Brooklyn | |

.jpg) Coney Island beach, amusement parks, and high rises as seen from the pier in June 2016 | |

|

Location in New York City | |

| Coordinates: 40°34′26″N 73°58′41″W / 40.574°N 73.978°WCoordinates: 40°34′26″N 73°58′41″W / 40.574°N 73.978°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | New York |

| City | New York City |

| Borough | Brooklyn |

| Settled | 17th century |

| Founded by | Dutch settlers |

| Area | |

| • Total | 0.6910000 sq mi (1.7896818 km2) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 24,711 |

| • Density | 36,000/sq mi (14,000/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC– 05:00 (Eastern Time Zone) |

| ZIP code | 11224 |

| Telephone area code | 718, 347, 929, and 917 |

Coney Island is a peninsular residential neighborhood, beach, and leisure/entertainment destination of Long Island on the Coney Island Channel, which is part of the Lower Bay in the southwestern part of the borough of Brooklyn in New York City. Coney Island was formerly the westernmost of the Outer Barrier islands on Long Island's southern shore, but in the early 20th century it became connected to the rest of Long Island by land fill. The residential portion of the peninsula is a community of 60,000 people in its western part, with Sea Gate to its west, Brighton Beach and Manhattan Beach to its east, the Lower Bay to the south, and Gravesend to the north.

Coney Island was originally part of the colonial town of Gravesend. By the mid-19th century, it became a seaside resort, and by the late 19th century, amusement parks were also built at the location. The attractions reached a historical peak during the first half of the 20th century, declining in popularity after World War II and following years of neglect. The area was revitalized with the opening of the MCU Park in 2001 and several amusement rides in the 2010s.

Geography

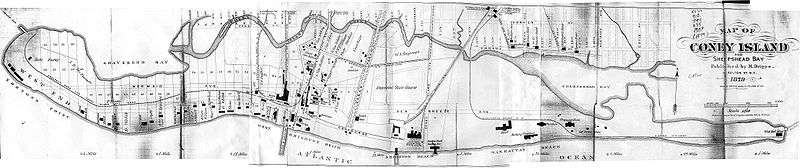

Coney Island is a peninsula on the western end of Long Island lying to the west of the Outer Barrier islands along Long Island's southern shore. The peninsula is about 4 miles (6.4 km) long and 0.5 miles (0.80 km) wide. It extends into Lower New York Bay with Sheepshead Bay to its northeast, Gravesend Bay and Coney Island Creek to its northwest, and the main part of Brooklyn to its north. At its highest it is 7 feet (2.1 m) above sea level. Coney Island was formerly an actual island, separated from greater Brooklyn by Coney Island Creek, and was the westernmost of the Outer Barrier islands. A large section of the creek was filled as part of a 1920s and 1930s land and highway development, turning the island into a peninsula.[1]

The perimeter of Coney Island features man made structures designed to maintain its current shape. The beaches are currently not a natural feature; the sand that is naturally supposed to replenish Coney Island is cut off by the jetty at Breezy Point, Queens.[2][3]:337 Sand has been redeposited on the beaches via beach nourishment since 1922-1923,[4] and is held in place by around two dozen groynes. A large sand-replenishing project along Coney Island and Brighton Beach took place in the 1990s.[3]:337 Sheepshead Bay on the north east side is, for the most part, enclosed in bulkheads.[3]

Name

The original Native American inhabitants of the region, the Lenape, called this area Narrioch. This name has been attributed the meaning of "land without shadows"[5] or "always in light"[6] describing how its south facing beaches always remained in sunlight. A second meaning attributed to Narrioch is "point" or "corner of land".[7]

The first documented European name for the island is the Dutch name Conyne Eylandt[8][9][10][11][12] or Conynge Eylandt.[13] This would roughly be equivalent to Konijn Eiland using modern Dutch spelling, meaning Rabbit Island.[14][15] The name was anglicized to Coney Island after the English took over the colony in 1664,[16][17][18][19] coney being the corresponding English word.[14][15][20]

There are several alternative theories for the origin of the name. One posits that it was named after a Native American tribe, the Konoh, who supposedly once inhabited it.[21] Another surmises that Conyn was the surname of a family of Dutch settlers who lived there.[21] Yet a third interpretation claims that "Conyne" was a distortion of the name of Henry Hudson's second mate on the Halve Maen, John Colman, who was slain by natives on the 1609 expedition and buried at a place they named Colman's Point, possibly coinciding with Coney Island.[8][21]

History

Early settlement

Giovanni da Verrazzano was the first European explorer to discover the island of Narrioch during his expeditions to the area in 1527 and 1529. He was subsequently followed by Henry Hudson.[22]:34 The Dutch established the colony of New Amsterdam in present-day Coney Island in the early 17th century. The Native American population in the area dwindled as the Dutch settlement grew and the entire southwest section of present-day Brooklyn was purchased in 1645 from the Native Americans in exchange for a gun, a blanket, and a kettle.[23][24]

In 1644, a colonist named Guysbert Op Dyck was given a patent for 88 acres of land in the town of Gravesend, on the southwestern shore of Brooklyn. The patent included Conyne Island, an island just off the southwestern shore of the town of Gravesend, as well as Conyne Hook, a peninsula just east of the island. At the time, both were part of Gravesend.[22]:4[13] East of Conyne Hook was the largest section of island called Gysbert's, Guysbert's, or Guisbert's Island (also called Johnson Island), containing most of the arable land and extending east through today's Brighton Beach and Manhattan Beach.[22]:34[25][26] This was officially the first official real estate transaction for the island.[13] Op Dyck never occupied his patent, and in 1661 he sold it off to Dick De Wolf. The land's new owner banned Gravesend residents from using Guisbert's Island and built a salt-works on the land, provoking outrage among Gravesend livestock herders. New Amsterdam was transferred to the English in 1664, and four years later, the English Governor created a new charter for Gravesend that excluded Coney Island. Subsequently, Guisbert's Island was divided into plots meted out to several dozen settlers. However, in 1685, the island became part of Gravesend again as a result of a new charter with the Native Americans.[22]:36

_Chart_of_the_entrance_of_Hudson's_River%2C_from_Sandy_Hook_to_New_York_-_with_the_banks%2C_depths_of_water%2C_sailing-marks%2C_%26ca_(NYPL_b14099970-1222740).png)

At the time of European settlement, the land that makes up the present-day Coney Island was divided across several separate islands. All of these islands were part of the outer barrier on the southern shore of Long Island, and their land areas and boundaries changed frequently.[22]:34 Only the westernmost island was called Coney Island; it currently makes up part of Sea Gate. At the time, it was a 1.25-mile shifting sandspit with a detached island at its western end extending into Lower New York Bay.[8] In a 1679–1680 journal, Jasper Danckaerts and Peter Sluyter noted that "Conijnen Eylandt" was fully separated from the rest of Brooklyn. The explorers observed:[8][22]:36

Nobody lives upon it, but it is used in winter for keeping cattle, horses, oxen, hogs and others, which are able to obtain there sufficient to eat the whole winter, and to shelter themselves from the cold in the thickets. This island is not so cold as Long Island or the Mahatans, or others, like some other islands on the coast, in consequence of their having more sea breeze, and of the saltness of the sea breaking upon the shoals, rocks and reefs, with which the coast is beset.[8][27][22]:36

By the early 18th century, the town of Gravesend was periodically granting seven-year-long leases to freeholders, who would then have the exclusive use of Coney Hook and Coney Island. In 1734, a road to Coney Hook was laid out.[22]:37 Thomas Stillwell, a prominent Gravesend resident who was the freeholder for Coney Island and Coney Hook at the time, proposed to build a ditch through Coney Hook so it would be easier for his cattle to graze. He convinced several friends in the nearby town of Jamaica to help him in this effort, telling them that the creation of such a ditch would allow them to ship goods from Jamaica Bay to New York Harbor without having to venture out into the ocean.[22]:37 In 1750, the "Jamaica Ditch" was dug through Coney Hook from Brown's Creek in the west to Hubbard's Creek in the east.[22]:34[28] The creation of the canal turned Coney Hook into a detached 0.5-mile-long (0.80 km) island called Pine Island, so named due to the woods on it.[22]:34

Each island was separated by an inlet that could only be crossed at low tide. By the end of the 18th century, the ongoing shifting of sand along the barrier islands had closed up the inlets to the point that residents began filling them in and joining them as one island. Development of Coney Island was slow until the 19th century due to land disputes, the American Revolutionary War, and the War of 1812.[26] Coney Island was so remote that Herman Melville wrote Moby-Dick on the island in 1849, and Henry Clay and Daniel Webster discussed the Missouri Compromise at the island the next year.[29]

Resort development

.jpg)

In 1824, the Gravesend and Coney Island Road and Bridge Company built the first bridge across Jamaica Ditch (by now known as Coney Island Creek), connecting the island with the mainland. The company also built a shell road across the island to the beaches.[26][30] In 1829, the company also built the first hotel on the island: the Coney Island House, near present day Sea Gate.[31]:8[32][30]

Due to Coney Island's proximity to Manhattan and other boroughs, and its simultaneous relative distance from the city of Brooklyn to provide the illusion of a proper vacation, it began attracting vacationers in the 1830s and 1840s, assisted by carriage roads and steamship service that reduced travel time from a formerly half-day journey to two hours.[33]:15 Most of the vacationers were wealthy and went by carriage. Inventor Samuel Colt built an observation tower on the peninsula in 1845, but he abandoned the project soon after.[32] In 1847, the middle class started going to Coney Island upon the introduction of a ferry line to Norton's Point—named after hotel owner Michael Norton—at the western portion of the peninsula. Gang activity started as well, with one 1870s writer noting that going to Coney Island could result in losing money and even lives.[32] The Brooklyn, Bath and Coney Island Railroad became the first railroad to reach Coney Island when it opened in 1864,[34][35] and it was completed in 1867.[36]:71

In 1868, William A. Engeman built a resort in the area.[37] The resort was given the name "Brighton Beach" in 1878 by Henry C. Murphy and a group of businessmen, who chose to name as an allusion to the English resort city of Brighton.[38][35] With the help of Gravesend's surveyor William Stillwell, Engeman acquired all 39 lots for the relatively low cost of $20,000.[39][31]:38 This 460-by-210-foot (140 by 64 m) hotel, with rooms for up to 5,000 people nightly and meals for up to 20,000 people daily, was close to the then-rundown western Coney Island, so it was mostly the upper middle class that went to this hotel.[40] The 400-foot (120 m), double-decker Brighton Beach Bathing Pavilion was also built nearby and opened in 1878, with the capacity for 1,200 bathers.[41][31]:38[35] "Hotel Brighton", also known as the "Brighton Beach Hotel", was situated on the beach at what is now the foot of Coney Island Avenue.[37] The Brooklyn, Flatbush, and Coney Island Railway, the predecessor to the New York City Subway's present-day Brighton Line, opened on July 2, 1878, and provided access to the hotel.[42][31]:38[43]

Simultaneously, wealthy banker August Corbin was developing adjacent Manhattan Beach after being interested in the area during a trip to the beach to heal his sick son.[37][44] Corbin, who worked on Wall Street and had many railroad investments, built the New York and Manhattan Beach Railway for his two luxury shoreline hotels. These hotels were used by the wealthy upper class, who would not go to Brighton Beach because of its proximity to Coney Island.[37] The 150-room Manhattan Beach Hotel—which was designed by J. Pickering Putnam and contained restaurants, ballrooms, and shops—was opened for business in July 1877 at a ceremony presided over by President Ulysses S. Grant.[44][45] The similarly prodigal Oriental Hotel, which hosted rooms for wealthy families staying for extended periods, was opened in August 1880.[44][46]

Andrew R. Culver, president of the Prospect Park and Coney Island Railroad,[47] had built a steam railway to West Brighton, the Culver Line, before Corbin and Engeman had even built their railroads. For 35 cents, one could ride the Prospect Park & Coney Island Railroad to the Culver Depot terminal at Surf Avenue.[37] Across the street from the terminal, the 300-foot (91 m) Iron Tower, bought from the 1876 Philadelphia Exposition, provided patrons with a bird's-eye view of the coast. The nearby "Camera Obscura" similarly used mirrors and lens to provide a panoramic view of the area.[37] Coney Island became a major resort destination after the Civil War as excursion railroads and the Coney Island & Brooklyn Railroad streetcar line reached the area in the 1860s and 1870s, followed by the Iron Steamboat Company ferry to Manhattan in 1881.[31]:29[36]:64

The 150-suite Cable Hotel was built nearby in 1875.[42] Next to it, on a 12-acre (4.9 ha) piece of land leased by James Voorhies, maitre d' Paul Bauer built the western peninsula's largest hotel, which opened in 1876.[37] By the turn of the century, Victorian hotels, private bathhouses, and vaudeville theaters were a common sight on Coney island.[48]:147 The three resort areas—Brighton Beach, Manhattan Beach and West Brighton—competed with each other for clientele, with West Brighton gradually becoming the most popular destination by the early 1900s.[49]

In the 1890s, Norton's Point on the western side of Coney Island was developed into Sea Gate, a gated summer community that catered mainly to the wealthy.[50][51] A private yacht carried visitors directly from the Battery at the southern tip of Manhattan Island. Notable tenants within the community included the Atlantic Yacht Club, which built a colonial style house along the waterfront.[52]

Theme park era

Between about 1880 and World War II, Coney Island was the largest amusement area in the United States, attracting several million visitors per year. At its height, it contained three competing major amusement parks, Luna Park, Dreamland, and Steeplechase Park, as well as many independent amusements.[48]:147–150 The area was also the center of new technological events, with electric lights, roller coasters, and baby incubators among the innovations at Coney Island in the 1900s. This continued through the end of World War II, with world's fair-style structures such as the Parachute Jump and Wonder Wheel.[48]:147

Charles I. D. Looff, a Danish woodcarver, built the first carousel and amusement ride at Coney Island in 1876, and hand-carved the designs into the carousel.[53] It was installed at Lucy Vandeveer's bath-house complex at West 6th Street and Surf Avenue. Looff subsequently commissioned another carousel at Feltman's Ocean Pavilion in 1880.[54]:88

From 1885 to 1896, the Elephantine Colossus, a seven story building (including a brothel) in the shape of an elephant, was the first sight to greet immigrants arriving in New York, who would see it before they saw the Statue of Liberty.[55] The Coney Island "Funny Face" logo, which is still extant, dates 100 years to the early days of George C. Tilyou's Steeplechase Park.[56]

Starting in the early 1900s, the City of New York made efforts to condemn all buildings and piers built south of Surf Avenue. It was an effort to reclaim the beach which by then had almost completely been built over with bath houses, clam bars, amusements, and other structures. The local amusement community opposed the city. Eventually a settlement was reached where the beach did not begin until 1,000 feet (300 m) south of Surf Avenue, the territory marked by a city-owned boardwalk, while the city would demolish any structures that had been built over public streets, to reclaim beach access.

When the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company electrified the steam railroads and connected Brooklyn to Manhattan via the Brooklyn Bridge at the beginning of the 20th century, Coney Island turned rapidly from a resort to an accessible location for day-trippers seeking to escape the summer heat in New York City's tenements.[42][57] In 1915, the Sea Beach Line was upgraded to a subway line, followed by the other former excursion roads, and the opening of the New West End Terminal in 1919 ushered in Coney Island's busiest era.[42][57]

In 1916, Nathan Handwerker started selling hot dogs at Coney Island for a nickel each. This later evolved into the Nathan's Famous hot dog chain.[29]

Since the 1920s, all property north of the boardwalk and south of Surf Avenue was zoned for amusement and recreational use only, with some large lots of property north of Surf also zoned for amusements only.

Conversion into peninsula

Through the turn of the 20th century Coney Island was still an island, being separated from the main part of Brooklyn by the 3-mile-long Coney Island Creek.[58] There were plans for several decades in the 19th century and early 20th century to dredge and straighten the creek as a ship canal, but they were abandoned. By 1924, local land owners and the city had filled a portion of the creek.[3]:337[1] A major section of the creek was further filled in to allow construction of the Belt Parkway in the 1930s, and the western and eastern ends of the island became peninsulas. More fill was added in 1962 with the construction of the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge.[59]

Residential development and decline

Robert Moses era

In 1937, New York City parks commissioner Robert Moses published a report about the possible redevelopment of Coney Island, as well as the Rockaway and the South Beach of Staten Island. Moses wrote of Coney Island, "There is no use bemoaning the end of the old Coney Island fabled in song and story. The important thing is not to proceed in the mistaken belief that it can be revived."[60] He further wrote that the boardwalk should be redeveloped, and that old buildings should be demolished to make way for parking facilities. As part of Moses's plan, a 0.67-mile (1.08 km) segment of the Coney Island beach would be rebuilt at a cost of $3.5 million.[60] This was originally rejected as being too expensive.[61] In August 1938, Moses submitted a plan to expand the Coney Island beach by 18 acres (7.3 ha) using shorefront from Brighton Beach.[62] The next year, Mayor Fiorello H. La Guardia endorsed Moses's revised plan to redevelop Coney Island as a city-operated park area, unifying all the discrete resorts under public control. The reconstruction of the Coney Island boardwalk could be achieved by purchasing a 400-foot-wide (120 m) strip of land along the shoreline, which would allow the boardwalk to be moved 300 feet (91 m) inland.[61] At this point, Coney Island was so crowded on summer weekends that Moses observed that a coffin would provide more space per person.[29]

In August 1944, Luna Park was severely damaged by a fire that burned half of the park.[63] Two years later, in August 1946, it was closed permanently and sold to a company who announced they were going to tear down what was left of Luna Park and build Quonset huts for military veterans and their families.[64] Moses asked the city to transfer its land along the Coney Island waterfront to the Parks Department. The city granted him that request in 1949.[65] Moses then had the land rezoned for residential use, with a stipulation that the complex must include low-income housing. He ultimately planned for "about a third" of attractions along Surf Avenue, one block north of the beach, to be demolished and replaced with housing.[66] Moses moved the boardwalk back from the beach several yards, demolishing many structures, including the city's municipal bath house. He would later demolish several blocks of amusements as well.[48]:149 He claimed that fewer amusement-seekers were going to Coney Island every year, because they preferred places where they could bathe outdoors, such as Jones Beach State Park on Long Island, rather than the "mechanical gadget" attractions of Coney Island.[66] Moses also announced that the Steeplechase Pier would be closed for a year so it could be renovated.[67]

In 1953, Moses proposed that most of the peninsula be rezoned for various uses, claiming that it would be an "upgrade" over the various business and unrestricted zones that existed at the time. Steeplechase Park would be allowed to remain open, but much of the shorefront amusements and concessions would be replaced by residential developments.[68][69] After many complaints from the public and from concession operators, the Estimate Board reinstated the area between West 22nd and West Eighth Streets as an amusement-only zone, with the zone extending 200 to 400 feet (61 to 122 m) inland from the shoreline.[70][71] Moses's subsequent proposal to extend the Coney Island boardwalk east to Manhattan Beach was denied in 1955.[72] A proposal to make the Quonset hut development into a permanent housing structure was also rejected.[73]

A new building for the New York Aquarium was approved for construction in the neighborhood in 1953.[74]:687[75] Construction started on the aquarium in 1954.[69] The development of the new New York Aquarium was expected to revitalize Coney Island.[76][69] By 1955, the Thompson Coaster had been demolished and replaced with a "hot rod" amusement ride. The area still included four children's amusement areas, five roller coasters, several flat and dark rides, and various other attractions such as Deno's Wonder Wheel.[76] The New York Aquarium's new site opened in June 1957.[77] At this point, there were still several dozens of rides on Coney Island.[29]

Fred Trump era

During the summers of 1964 and 1965, there was a large decrease in the number of visitors to Coney Island because of the 1964/1965 World's Fair at Flushing Meadows–Corona Park in Queens.[78] Crime increases, insufficient parking facilities, bad weather, and the post-World War II automotive boom were also cited as contributing factors in the visitor decrease. During the summer of 1964, concessionaires saw their lowest profits in a quarter-century. Ride operators reported that they had 30% to 90% fewer visitors in 1964 compared to the previous year.[79]

In 1964, Coney Island's last remaining large theme park, Steeplechase Park, was closed and subsequently demolished.[80][54]:172 The surrounding blocks were filled with amusement rides and concessions that were closed or about to close.[54]:172 The rides at Steeplechase Park were auctioned off, and the property was sold to developer Fred Trump, the father of developer and U.S. president Donald Trump. In 1965, Fred Trump announced that wanted to build luxury apartments on the old Steeplechase property.[81] At the time, residential developments on Coney Island in general were being built at a rapid rate. The peninsula, which had 34,000 residents in 1961, was expected to have more than double that number by the end of 1964. Many of the new residents moved into middle-income co-operative housing developments such as Trump Village, Warbasse Houses, and Luna Park Apartments; these replaced what The New York Times described as "a rundown sprawl of rickety houses".[82] Developers were spending millions of dollars on new housing developments, and by 1966, the peninsula housed almost 100,000 people.[78]

Trump destroyed Steeplechase Park's Pavilion of Fun during a highly publicized ceremony in September 1966.[54]:172[83] In its stead, Trump proposed building a 160-foot-high (49 m) enclosed dome with recreational facilities and a convention center, a plan which was supported by Brooklyn borough president Abe Stark.[84] That summer, developers tried to revitalize the Coney Island boardwalk as an amusement area.[78] In October 1966, the city announced its plans to acquire the 125 acres (51 ha) of the former Steeplechase Park so that the land could be reserved for recreational use.[85] Although residents supported the city's action, Trump called the city's proposal "wasteful".[86] In January 1968, New York City parks commissioner August Heckscher II proposed that the New York state government build an "open-space" state park on the Steeplechase site,[87] and that May, the New York City Board of Estimate voted in favor of funding to buy the land from Trump.[88] Condemnation of the site started in 1969.[89] The city ultimately purchased the proposed park's site for $4 million, with partial funding from the federal government. As a condition of the deal, the sale or lease of the future parkland required permission from the New York State Legislature.[90]

Trump filed a series of court cases related to the proposed residential rezoning, and ultimately won a $1.3 million judgment.[89] The Steeplechase Park site laid empty for several years. Trump started subleasing the property to Norman Kaufman, who ran a small collection of fairground amusements on a corner of the site, calling his amusement park "Steeplechase Park".[54]:172[89] The city also leased the boardwalk and parking lot sites at extremely low rates, which resulted in a $1 million loss of revenue over the following seven years. Since the city wanted to build the state park on the site of Kaufman's Steeplechase Park, it attempted to evict him by refusing to grant a lease extension.[91]

By 1975, the city was considering demolishing the Coney Island Cyclone in favor of an extension of the adjacent New York Aquarium.[48]:153 The Aquarium supported the Cyclone's demolition, while the Coney Island Chamber of Commerce opposed it.[93] After a refurbishment by Astroland, the Cyclone reopened for the summer 1975 season.[94] The abandoned Parachute Jump was left in situ. However, in 1977, the New York City Planning Commission declined a proposal to grant landmark status to the attraction, as it intended to tear down the Parachute Jump.[54]:174[95]

The city continued to pursue litigation over the site occupied by Norman Kaufman. For over ten years, the city was unsuccessful in its efforts. It had no plan for the proposed state park, and in 1975 the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development nearly withdrew a proposed grant of $2 million to fund the proposed park.[91] The city ultimately accepted the grant. However, in June 1977, the city's parks commissioner suggested that the city would redevelop the original Steeplechase Park's site as an amusement area instead of an open-space state park, and proposed that the city return the grant. This move was opposed by the chairman of the New York City Planning Commission, who wanted to use the grant to pay for pedestrian walkways at the Steeplechase site.[96] In 1977 and 1978, Kaufman withheld rent payments to the city because of the ongoing litigation, and he sued the city for $1.7 million. By 1979, Kaufman had expanded his park and had plans to eventually rebuild the historic Steeplechase Park. He had also bought back the original Steeplechase horse ride with plans to install it the following season.[89] Although the city purchased Steeplechase Park from Fred Trump in 1979, Kaufman continued to operate the site until the end of summer 1980. In June 1981, the city paid Kaufman a million dollars for the rides; even though the amusements were estimated to be worth much less than that, the city finally succeeded in evicting Kaufman from the property.[97]

In 1979, the state announced that it would be conducting a report on the feasibility of legalizing gambling in New York State, Mayor Ed Koch proposed that the state open casinos in New York City to revitalize the area's economy.[98] Koch later clarified that he would support gambling in New York City if a casino were to be built either in Coney Island or the Rockaways, but not in midtown Manhattan, and if the city received certain shares of table game and slot machine profits.[99] There was substantial controversy over the plans to place a gambling site in Coney Island.[100] The state's interest in legalizing gambling subsided by 1981, and the idea was largely abandoned.[97] Additionally, the prospect of selling property to rich casino owners created a land boom where property was bought up and the rides cleared in preparation of reselling to developers. As gambling was never legalized for Coney, the area ended up with vacant lots.

Revival

Bullard deal and demolition of Thunderbolt

In the mid-1980s, restaurant mogul Horace Bullard approached the city to allow him to rebuild Steeplechase Park. He had already bought several acres of property just east of the Steeplechase Park site, including the property with a large coaster called Thunderbolt and property west of Abe Stark rink.[48]:150 His plans called for using his property, as well as the Steeplechase property and the unused property on the Abe Stark site, to build a $55 million theme park based on the original. The city agreed, and the project was approved in 1985.[48]:150[90] Bullard's amusement park, to be bounded by West 15th and 19th Streets between Surf Avenue and the Boardwalk, would be open by summer 1986 to coincide with the Statue of Liberty's centennial.[90] However, bureaucracies held up the project while the New York City Planning Commission compiled an environmental impact report. Other proposals for the area included a $7.9 million restoration of the boardwalk, as well as a new high-school and college sports stadium.[101]

In December 1986, the New York State Urban Development Corporation formally proposed the construction of a $58 million minor-league baseball stadium on the land bounded by West 19th and 22nd Streets, Surf Avenue, and the boardwalk, sandwiched between Bullard's development to the west and the New York Aquarium to the east. Negotiations were ongoing with the Mets and Yankees to ensure their support for the minor-league stadium[102] The next year, state senator Thomas Bartosiewics attempted to block Bullard from building on the Steeplechase site. Bartosiewics was part of a group called The Brooklyn Sports Foundation which had promised another theme park developer, Sportsplex, the right to build on the site. Construction was held up for another four years as Bullard and Sportsplex fought over the site.

In 1994, after Rudy Giuliani took office as mayor of New York, he negated the Bullard deal by building Keyspan Park, the minor-league baseball stadium, on the site allotted for Steeplechase Park.[48]:150 Giuliani stated that he wanted to build Sportsplex, provided that it included the stadium for a minor-league team owned by the Mets. By doing this, Giuliani wanted to improve sports facilities in the area, as well as found a professional baseball team in Brooklyn.[103]

As soon as the stadium was completed, Giuliani nullified the Sportsplex deal and had the parking lot built, angering many in the community.[104] The Mets decided the minor league team would be called the Brooklyn Cyclones and sold the naming rights to the stadium to Keyspan Energy. Executives from Keyspan complained that the stadium's line of view from the rest of Coney Island amusement area was blocked by the now derelict Thunderbolt coaster and considered not going through with the deal. Bullard, now no longer rebuilding Steeplechase Park, had wanted to restore the Thunderbolt as part of a scaled-down amusement park. The following month, Giuliani had the coaster demolished on the grounds that the Thunderbolt was about to collapse. The full destruction of the supposedly structurally unstable coaster took weeks.[48]:150

Thor Equities ownership

In 2003, Mayor Michael Bloomberg took an interest in revitalizing Coney Island as a possible site for the New York City bid of the 2012 Summer Olympics. A plan was developed by the Astella Development Corporation. When the city lost the bid for the Olympics, revitalization plans were passed on to the Coney Island Development Corporation (CIDC), which came up with a plan to restore the resort.[105]

Shortly before the CIDC's plans were to be publicly released, a development company named Thor Equities, purchased all of Bullard's 168,000-square-foot (15,600 m2) western property for $13 million, almost six times what it had been valued at. In less than a year, Thor sold the property to Taconic Investment Partners for over $90 million.[48]:158 Taconic now had 100 acres (40 ha), on which it planned to build 2,000 apartment units.[48]:158–159[106] Thor then went about using much of its $77 million profit to purchase property well over market value lining Stillwell Avenue and offered to buy out every piece of property inside the traditional amusement area. Quickly, rumors started that Thor was interested in building a retail mall in the heart of the amusement area.[48]:158–159

In September 2005, Thor's founder, Joe Sitt, unveiled his new plans for a large Bellagio-style hotel resort surrounded by rides and amusements. Sitt released renderings of a hotel that would take up the entire amusement area from the Aquarium to beyond Keyspan Park. The CIDC report suggested adding year-round commercial and amusement area, and recommended tha property north of Surf Avenue and west of Abe Stark's land could be rezoned for other uses including residential to lure developers into the area.[105]

Astroland owner Carol Hill Albert, whose husband's family had owned the park since 1962, sold the site to Thor in November 2006 for an undisclosed amount. In January 2007, Thor released renderings for a new amusement park to be built on the Astroland site called Coney Island Park.[107] Thor proposed a $1.5 billion renovation and expansion of the Coney Island amusement area to include hotels, shopping, movies, an indoor water park and the city's first new roller coaster since the Cyclone. The Municipal Art Society launched the initiative ImagineConey,[108] in early 2007, as discussion of a rezoning plan that highly favored housing and hotels began circulating from the DCP.[109] MAS held several public workshops, a call for ideas, and a charrette to garner attention to the issue. Astroland closed in 2008[110] and was replaced by a new Dreamland in 2009 and by a new Luna Park in 2010.

The DCP certified the rezoning plan in January 2009 to negative responses from all amusement advocates and Coney Island enthusiasts. In 2012 the plan was working through the ULURP process.[111] Thor Equities said it hoped to complete the project by 2011.[112] Thor Equities planned to demolish most of the iconic, early 20th-century buildings along Surf Avenue. In their place, Sitt planned to build cheap, one-story retail, and his recently released rendering clearly shows Burger King and Taco Bell-like buildings.[113] The Aquarium was also planning a renovation.[114] In June 2009, the city's planning commission unanimously approved the construction of 4,500 units of housing and 900 affordable units and vowed to "preserve, in perpetuity, the open amusement area rides that everyone knows and loves," while protesters argued that "20 percent affordable-housing component is unreasonably low."[115]

2010s

Besides Luna Park, the remaining parks and attractions include Deno's Wonder Wheel Amusement Park, 12th Street Amusements, and Kiddie Park, while the Eldorado Arcade has an indoor bumper car ride. The Zipper and Spider on 12th Street were closed permanently on September 4, 2007, and dismantling began after its owner lost his lease. They have since been reassembled at an amusement park in Honduras.[116]

On April 20, 2011, the first new roller coasters to be built at Coney Island in eighty years were opened as part of efforts to reverse the decline of the amusement area.[117] The Thunderbolt steel roller coaster, named after the original wooden coaster on the site, was opened in June 2014.[118]

In 2012, Hurricane Sandy caused major damage to the Coney Island amusement parks, the Aquarium, and businesses. Nathan's, however, reported that the Nathan's Hot Dog Eating Contest would be held the following summer, as usual.[119] Luna Park at Coney Island reopened on March 24, 2013.[120] Rebuilding of the aquarium started in early 2013, and a major expansion of the aquarium opened in summer 2018.[121][122]

In August 2018, the NYCEDC and NYC Parks announced that the Coney Island amusement area would be expanded. The new rides would be located on a 150,000-square-foot (14,000 m2) city-operated parcel between West 15th and West 16th Streets, next to the new Thunderbolt coaster. The rides, to be operated by Luna Park, would include a 40-foot-high (12 m) log flume to be opened in 2020, as well as a zip-line and a ropes course that would open in 2019.[123][124] There would also be a public plaza and an amusement arcade within the newly expanded amusement area.[124][125] The same month, it was also announced that a 50-room boutique hotel was being planned for Coney Island. The hotel would be located within the former Shore Theater on Surf and Stillwell Avenues, which had been abandoned since 1978. If built, the hotel would be the first to be constructed in Coney Island in more than half a century.[126][127] The city also expressed its intent to demolish the Abe Stark Rink and redevelop the site, as per the 2009 rezoning, though residents wanted NYC Parks to retain control over the site rather than sell it off to a private developer.[128]

Theme parks and attractions

Currently, Coney Island has two amusement parks — Luna Park and Deno's Wonder Wheel Amusement Park — as well as several rides that are not incorporated into either theme park. Coney Island also has several other visitor attractions and hosts renowned events as well. Coney Island's amusement area is one of a few in the United States that is not mostly owned by any one entity.[48]:153

Rides

Current rides

The current amusement park contains various rides, games such as skeeball and ball tossing, and a sideshow, including games of shooting, throwing, and tossing skills. The rides and other amusements at Coney Island are owned and managed by several different companies and operate independently of each other. It is not possible to purchase season tickets to the attractions in the area.

Three rides at Coney Island are protected as designated New York City landmarks and are listed in the National Register of Historic Places. These three rides are:

- Wonder Wheel – built in 1918 and opened in 1920, this steel Ferris wheel has both stationary cars and rocking cars that slide along a track. It holds 144 riders, stands 150 ft (46 m) tall, and weighs over 200 tons. At night, the Wonder Wheel's steel frame is outlined and illuminated by neon tubes.[129] It is located at Deno's Wonder Wheel Amusement Park.

- The Cyclone roller coaster – built in 1927, it is one of the United States's oldest wooden coasters still in operation. Popular with roller coaster aficionados, the Cyclone includes an 85 ft (26 m), 60-degree drop. It is owned by the City of New York, and was operated by Astroland, under a franchise agreement. It is now located in and operated by Luna Park.

- Parachute Jump – originally built as the Life Savers Parachute Jump at the 1939 New York World's Fair, this was the first ride of its kind. Patrons were hoisted 262 ft (80 m) in the air before being allowed to drop using guy-wired parachutes. Although the ride has been closed since 1964, it remains a Coney Island landmark and is sometimes referred to as Brooklyn's Eiffel Tower.[80] Between 2002 and 2004, it was completely dismantled, cleaned, painted, and restored, but remains inactive. After an official lighting ceremony in July 2006, the Parachute Jump was slated to be lit year-round using different color motifs to represent the seasons. However, this idea was scrapped when New York City started conserving electricity in the summer months, and it has not been lit regularly since.

Other notable, currently operating attractions include:

- Thunderbolt – In March 2014, construction started on the new Thunderbolt coaster at Coney Island. The Thunderbolt was manufactured by Zamperla at a cost of US$10 million. The ride features 2,000 feet (610 m) of track, a height of 125 feet (38 m), and a top speed of 65 miles per hour (105 km/h).[130] Thunderbolt features three inversions including a vertical loop, corkscrew, and an Immelmann loop.[131][132][133][134] The Thunderbolt is located near Surf Avenue and West 15th Street in Coney Island will be constructed with 2,233 feet of track that will stretch to a height of 115 feet and was built next to the B&B Carousell, Coney Island's last remaining historic carousel. The opening of the Thunderbolt occurred on June 14, 2014.[135]

- B&B Carousell [sic] (as spelled by the frame's builder, William F. Mangels) – this is Coney Island's last traditional carousel, near the old entrance to Luna Park. The carousel was built circa 1906–1909 with a traditional roll-operated fairground organ. When the long-term operator died unexpectedly, the carousel was put up for auction, with fears that it would leave Coney Island or be broken up for sale to collectors. However, the City of New York bought the B&B Carousell a few days before the auction; it was dismantled and rebuilt in Steeplechase Plaza, a 2.2-acre public plaza. It was relocated to Luna Park in 2013[136] and listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2016.[137][138]

- Bumper cars – there are three separate bumper car rides on Coney Island, located on 12th street, Deno's Wonder Wheel Park, and Eldorado's Arcade on Surf Avenue.

- Haunted houses – two traditional dark ride haunted houses operate at Coney Island, Spook-a-Rama at Deno's and Ghost Hole on West 12th Street.

Former rides

Former rides include:

- Thunderbolt – this roller coaster across the street from Steeplechase Park was constructed in 1925 and closed in 1983. It was torn down by the city "to protect public safety" in 2000 during the construction of nearby Keyspan Park. In the Woody Allen movie Annie Hall, Allen's character's family lives in the small house-like structure under the rear of the roller coaster track.

- Tornado – this roller coaster was constructed in 1926. It suffered a series of small fires which made the structure unstable, and was torn down in 1977.

- Steeplechase Park Horse Race – created by a Coney Island resident George C. Tilyou in 1897, this ride consisted of people riding wooden horses around the park on a steel track.[139]

Beach

.jpg)

The sand beach at the west end of Coney Island at Sea Gate is private, only accessible to residents.[140] There is a broad public sand beach that starts at Sea Gate at West 37th Street, through the central Coney Island area and Brighton Beach, to the beginning of the community of Manhattan Beach, a distance of approximately 2.5 mi (4.0 km). The beach is continuous and is served for its entire length by the broad Riegelmann Boardwalk. A number of amusements are directly accessible from the land-side of the boardwalk, as is the aquarium and a variety of food shops and arcades. There is a 1,300-foot (400 m) long public beach further down in the community of Manhattan Beach.[140]

The public beaches are groomed on a regular basis by the city. Because sand no longer naturally deposits on the beach, it is replenished in regular beach nourishment projects using dredged sand.[2] The south facing beach is without significant obstructions and is in sunlight all day. The public beaches are open to all without restriction, and there is no charge for use. The beach area is divided into "bays", areas of beach delineated by rock groynes, which moderate erosion and the force of ocean waves.

The Coney Island Polar Bear Club consists of a group of people who swim at Coney Island throughout the winter months, most notably on New Year's Day, when additional participants join them to swim in the frigid waters.

The beach serves as the training grounds for the Coney Island Brighton Beach Open Water Swimmers (CIBBOWS),[141] a group dedicated to promoting open water swimming for individuals of all levels. CIBBOWS hosts several open water swim races each year, such as Grimaldo's Mile and the New York Aquarium 5k, as well as regular weekend training swims.[141]

Public parks

- The Abe Stark Skating Rink was opened in 1970. It is located on the south side of Surf Avenue between West 19th and West 20th Streets, adjacent to the boardwalk.[142]

- Coney Island Creek Park, which opened in 1984, is located along the south shore of Coney Island Creek and is composed mostly of plants.[143]

- Leon S. Kaiser Park is located on the northern side of Neptune Avenue between West 24th and West 32nd Streets, and contains playgrounds, athletic facilities, fitness equipment, and open spaces for barbecuing.[144]

- Poseidon Playground is located along the beach between West 25th and West 27th Streets, and contains water spray showers, playgrounds, and handball courts.[145]

- Surf Playground is located on the south side of Surf Avenue between West 25th and West 27th Streets, just north of Poseidon Playground. It contains basketball courts, playgrounds, and water spray showers.[146]

Other attractions

The New York Aquarium, which opened in 1957 on the former site of the Dreamland amusement park, is another attraction on Coney Island.[77]

In 2001, KeySpan Park opened on the former site of Steeplechase Park to host the Brooklyn Cyclones minor league baseball team.

In May 2015, Thor Equities unveiled Coney Art Walls, a public art wall project curated by former director of the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) Jeffrey Deitch and Thor CEO Joseph Sitt. Located at 3050 Stillwell Avenue, the project featured more than 30 world renowned artists including legends such as Lady Pink, Crash, Daze, Futura and Kenny Scharf, as well as leading artists of the next generation including Shepard Fairey, Maya Hayuk and How & Nosm. Coney Art Walls returned in 2016 with 21 new murals, including several of the leading paintings and sculptors in New York, in addition to leading artists connected with street culture.[1]

In June 2016, the Ford Amphitheater at Coney Island opened on the boardwalk, hosting several live musical acts as well as other events. Construction began in 2015.[147] It was constructed at the location of the Childs Restaurant on the Coney Island Boardwalk. The restaurant was originally constructed in 1923, and was renovated when the amphitheater was being constructed. The rooftop part of the restaurant opened back up in July 2016 and the main restaurant is scheduled to reopen in 2017.[148]

Events

The Coney Island Mermaid Parade takes place on Surf Avenue and the boardwalk, and features floats and various acts. It has been produced annually by Coney Island USA, a non-profit arts organization established in 1979, dedicated to preserving the dignity of American popular culture.

Coney Island USA has also sponsored the Coney Island Film Festival every October since 2000, as well as Burlesque At The Beach, and Creepshow at the Freakshow (an interactive Halloween-themed event). It also houses the Coney Island Museum.

The annual Cosme 5K Charity Run/Walk, supported by the Coney Island Sports Foundation (CISF), takes place on the last Sunday of June on the Riegelmann Boardwalk.

In August 2006, Coney Island hosted a major national volleyball tournament sponsored by the Association of Volleyball Professionals. The tournament, usually held on the west coast of the United States, was televised live on NBC. The league built a 4,000-seat stadium and twelve outer courts next to the boardwalk for the event.[149] The tournament returned to Coney Island in 2007 and 2008.

In April 2009, Feld Entertainment, parent company to Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus, announced that "The Greatest Show on Earth" would perform on Coney Island for the entire summer of 2009, the first time since July 16, 1956 that Ringling Bros. had performed in this location. The tents were located between the boardwalk and Surf Avenue, and the show was called The Coney Island Boom-A-Ring. In 2010, they returned to the same location with The Coney Island Illuscination.[150]

Demographics

Based on data from the 2010 United States Census, the combined population of Coney Island and Sea Gate was 31,965, a decrease of 2,302 (6.7%) from the 34,267 counted in 2000. Covering an area of 851.49 acres (344.59 ha), the neighborhood had a population density of 37.5 inhabitants per acre (24,000/sq mi; 9,300/km2).[151] The entirety of Community Board 13 had 106,702 inhabitants as of NYC Health's 2015 Community Health Profile, with an average life expectancy of 79.7 years.[152]:2 This is near the median life expectancy for New York City neighborhoods.[153]:53 (PDF p. 84) Most inhabitants are adults, with 24% between the ages of 25–44, 27% between 45–64, and 21% who are at least 65 years old. The ratio of young and college-aged residents was lower, at 19% and 8% respectively.[152]:2 Coney Island's elderly population, as a share of the area's total population, is higher than in other New York City neighborhoods.[154]:6

The racial makeup of the neighborhood was 32.2% (10,307) African American, 30.9% (9,880) White, 8.7% (2,793) Asian, 0.2% (78) Native American, 0.0% (4) Pacific Islander, 0.2% (67) from other races, and 1.5% (467) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 26.2% (8,369) of the population.[155] 82% of the population were high school graduates and 40% had a bachelor's degree or higher.[155] This was reflected in the Community Health Profile.[152]:2

As of 2016, the median household income in Community District 13 was $39,213.[156] In 2015, an estimated 27% of Coney Island residents lived in poverty, compared to 24% in all of Brooklyn and 21% in all of New York City. One in eight residents (12%) were unemployed, compared to 11% in the rest of both Brooklyn and New York City. Rent burden, or the percentage of residents who have difficulty paying their rent, is 56% in Coney Island, slightly higher than the citywide and boroughwide rates of 51% and 52% respectively.[152]:6

Police and crime

The NYPD's 60th Precinct is located at 2950 West Eighth Street.[157] Transit District 34 is located at 1243 Surf Avenue, within the Coney Island–Stillwell Avenue subway station.[158]

The 60th Precinct ranked 34th safest out of 69 city precincts for per-capita crime in 2010. Between 1993 and 2010, major crimes decreased by 72%, including a 76% decrease in robberies, 71% decrease in felony assaults, and 67% decrease in shootings.[159] With a non-fatal assault rate of 64 per 100,000 people, Coney Island's rate of violent crimes per capita is almost equal to that of the city as a whole.[152]:7 The 60th Precinct has a lower crime rate than in the 1990s, with crimes across all categories having decreased by 85.5% between 1990 and 2017. The precinct saw 8 murders, 16 rapes, 142 robberies, 235 felony assaults, 61 burglaries, 382 grand larcenies, and 49 grand larcenies auto in 2017.[160]

Fire safety

The firehouse for the New York City Fire Department (FDNY)'s Engine Co. 318/Ladder Co. 166 is located at 2510 Neptune Avenue. FDNY EMS Station 43 is in the area on the grounds of Coney Island Hospital, the largest station in NYC.[161]

Health

Preterm and teenage births are slightly more common in Coney Island than in other places citywide. In Coney Island, there were 11.3 preterm births per 1,000 live births (compared to 9.0 per 1,000 citywide), and 25.8 teenage births per 1,000 live births (compared to 23.6 per 1,000 citywide), slightly lower than in the median neighborhood.[152]:7 Coney Island has a high population of residents who are uninsured, or who receive healthcare through Medicaid.[154] In 2015, this population of uninsured residents was estimated to be 27%, which is higher than the citywide rate of 20%.[152]:10

Air pollution in Coney Island is 0.008 milligrams per cubic metre (8.0×10−9 oz/cu ft), lower than the citywide and boroughwide averages.[152]:5 Eighteen percent of Coney Island residents are smokers, which is slightly higher the city average of 15% of residents being smokers. In Coney Island, 31% of residents are obese and 11% are diabetic, higher than the citywide averages of 24% and 10% respectively. Ninety-two percent of residents eat some fruits and vegetables every day, which is slightly higher than the city's average of 88%.[152]:8–9 In 2015, three out of five residents (62%) described their health as "good," "very good," or "excellent," among the lowest rates in the city.[152]:2 There are 7 tobacco stores per 10,000 people (compared to the 11 tobacco stores per ten-thousand people both in Brooklyn and in New York City as a whole), but there are also 86 square feet (8.0 m2) of supermarket footage per 100 people, lower than the citywide average of 177 square feet (16.4 m2) per hundred people and the boroughwide average of 156 square feet (14.5 m2) per hundred people.[152]:5

The primary hospital in the neighborhood is Coney Island Hospital.[154]:6

Education

Elementary, middle, and high schools

Coney Island is served by the New York City Department of Education, and students in the neighborhood are automatically "zoned" into the nearest public schools. Coney Island's zoned schools include PS 90 Edna Cohen School for K-5 education[162][163] PS 329 (Pre K-5),[164] PS 188 The Michael E. Berdy School (K-4),[165] PS 100 Coney Island School (K-5),[166][167] IS 303 Herbert S. Eisenberg,[167][168][169] and PS/IS 288 The Shirley Tanyhill School (Pre-K-8).[170] IS 239, the Mark Twain School for the Gifted and Talented (6–8), is a magnet school for gifted students, and it accepts students from around the city.[171] In 2006, David Scharfenberg of The New York Times said, "Coney Island's elementary schools are a mixed lot, with only some exceeding citywide averages on the state's testing regimen."[167]

There are no zoned high schools, though Abraham Lincoln High School, an academic high school, is in Coney Island.[167][172] Rachel Carson High School for Coastal Studies is located in Coney Island.[173] Nearby high schools include:

- John Dewey High School

- The Leon M. Goldstein High School for the Sciences

- William E. Grady Vocational High School

- The High School Of Sports Management

- Liberation High School

Public library

Brooklyn Public Library (BPL) operates the Coney Island Library at 1901 Mermaid Avenue, near the intersection with West 19th Street. It opened in 1911 as an unmanned deposit station. Ten years later, it moved to the former Coney Island Times offices and became fully staffed. In 1954 another branch was built. According to BPL's website, the library was referred to as "the first-ever library built on stilts over the Atlantic Ocean." The branch was rebuilt in 2013 following Hurricane Sandy.[174]

Transportation

Coney Island is served by three New York City Subway stations.[175][176] The Coney Island–Stillwell Avenue station, which is the terminal of the D, F, N, and Q trains, is one of the largest elevated rapid transit stations in the world, with eight tracks serving four platforms.[177] The entire station, built in 1917–1920 as a replacement for the former surface-level Culver Depot,[178] was rebuilt in 2001–2004.[179][177] The other subway stations within Coney Island are West Eighth Street–New York Aquarium, which is served by the F and Q trains, and Ocean Parkway, which is served by the Q train.[176]

A bus terminal beneath the Stillwell Avenue station serves the B68 to Prospect Park, the B74 to Sea Gate, the B64 to Bay Ridge, and the B82 to Starrett City. The B36 runs from Sea Gate to Sheepshead Bay, Brooklyn. The X28 provides express bus service to Manhattan on weekdays.[180]

The three main west-east arteries in the Coney Island community are, from north to south, Neptune Avenue, Mermaid Avenue, and Surf Avenue. Neptune Avenue crosses through Brighton Beach before becoming Emmons Avenue at Sheepshead Bay, while Surf Avenue becomes Ocean Parkway and then runs north toward Prospect Park. The cross streets in the Coney Island neighborhood proper are numbered with "West" prepended to their numbers, running from West 1st Street to West 37th Street at the border of Sea Gate (except for Cropsey Avenue, which becomes West 17th Street south of Neptune Avenue).[181]

The Ocean Parkway bicycle path terminates in Coney Island. The Shore Parkway bikeway runs east along Jamaica Bay, and west and north along New York Harbor. Street bike lanes are marked in Neptune Avenue and other streets in Coney Island.[182]

Tentative plans call for NYC Ferry service to stop at Coney Island,[183] although this has not yet been confirmed.[184][185]

In popular culture

Coney Island has been featured in many novels, films, television shows, cartoons, and theatrical plays.[54]:176[186]

References

Notes

- 1 2 3 "Photo of the Week". March 4, 2016.

- 1 2 U.S. Geological Survey, Geology of National Parks, 3D and Photographic Tours, 72. Coney Island, United States Department of the Interior. Accessed December 15, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 "Chapter 17, Southern Brooklyn". A Stronger, More Resilient New York (PDF). City of New York. 2013. pp. 335–364. Retrieved July 22, 2018.

- ↑ Dornhelm, Richard B. (September 25, 2003). The Coney Island Public Beach and Boardwalk Improvement of 1923. Reston, VA: American Society of Civil Engineers. doi:10.1061/40682(2003)6. ISBN 978-0-7844-0682-3.

- ↑ "Coney Island" (PDF). Retrieved March 1, 2014.

- ↑ Brooklyn before the bridge: American paintings from the Long Island Historical Society, Long Island Historical Society, Brooklyn Museum Brooklyn Museum – 1982, page 54

- ↑ Evan T. Pritchard, Native New Yorkers: The Legacy of the Algonquin People of New York, Council Oak Books – 2002, page 105

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hunter, Douglas (2009). Half Moon: Henry Hudson and the Voyage that Redrew the Map of the New World. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. p. 278. ISBN 1608190986.

- ↑ Seymour I. Schwartz and Ralph E. Ehrenberg, The mapping of America, H.N. Abrams publishing, 1980, p. 108

- ↑ Joan Vinckeboons (Johannes Vingboon), "Manatvs gelegen op de Noot Riuier", 1639. Coney Island is labelled "Conyne Eylandt". Image of Vinckeboons map at Library of Congress.

- ↑ "De Nieu Nederlandse Marcurius", Volume 16, No. 1: February 2000. This is the newsletter of the New Netherland Project. Cites New Netherland map labeling "Conyne Eylandt" in 1639 Johannes Vingboon map.

- ↑ Library of Congress New Netherland website lists Conyne Eylandt as Dutch name for Coney Island.

- 1 2 3 Currie, George (August 10, 1936). "Passed in Review". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. p. 14. Retrieved July 21, 2018 – via Brooklyn Public Library; newspapers.com.

- 1 2 Sijs van der, Nicoline (2009). Cookies, Coleslaw, and Stoops: The Influence of Dutch on the North American Languages. p. 51. ISBN 978-9089641243.

- 1 2 "The Atlantic World: Dutch Place Names". The Dutch in America, 1609-1664. The Library of Congress. Retrieved May 10, 2016.

- ↑ Robert Morden, "A Map of ye English Empire in the Continent of America", 1690. Coney Island is labelled "Conney Isle". Image of Morden map at SUNY Stony Brook.

- ↑ Henry Popple, "A Map of the British Empire in America", Sheet 12, 1733. Coney Island is labelled "Coney Island". Image of Popple Map can be found at David Rumsey Map Collection Archived April 16, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Joseph DesBarre's chart of New York harbor in the 1779 work Atlantic Neptune, which can be found in Eric W. Sanderson, (2009). Mannahatta: A Natural History of New York City p. 47; in 1779 the island was a cluster of three low hummocks in the shallow "East Bank" flats at the eastern end of Gravesend Bay.

- ↑ John H. Eddy, "Map Of The Country Thirty Miles Round the City of New York", 1811. Coney Island is labeled "Coney I." Image of Eddy Map can be found at David Rumsey Map Collection Archived April 16, 2007, at the Wayback Machine..

- ↑ "coney". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved March 2, 2018.

- 1 2 3 "American Experience — Coney Island Gets a Name". pbs.org.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Stockwell, A.P.; Stillwell, W.H. (1884). A History of the Town of Gravesend, N.Y. Retrieved July 21, 2018.

- ↑ Pritchard, E.T. (2002). Native New Yorkers: The Legacy of the Algonquin People of New York. Council Oak Books. p. 106. ISBN 978-1-57178-107-9. Retrieved July 21, 2018.

- ↑ Douglass, Harvey (March 23, 1933). "Coney Island Scenes Shift, Never Change". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Retrieved March 23, 2016 – via Brooklyn Public Library; newspapers.com.

- ↑ Ierardi, Eric (2001). Gravesend, the home of Coney Island. Charleston, S.C: Arcadia. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-7385-2361-3. OCLC 51632931.

- 1 2 3 "Coney Island History - Early History". Heart of Coney Island.

- ↑ The Journal of Jasper Danckaerts, with an introduction by Bryan Wright.

- ↑ "Jamaica Ditch". Coney Island History Project. Retrieved July 21, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Roosevelt, Edith Kermit (June 1, 1957). "Coney Isle Fishing For Way to Regain Its Lost Glamour" (PDF). Buffalo Evening News. Retrieved July 26, 2018 – via fultonhistory.com.

- 1 2 "Yellowed Pages of Coney Island Register Reveal Visits of Many Great and Near-Great of Day". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. March 5, 1939. p. 11. Retrieved July 21, 2018 – via Brooklyn Public Library; newspapers.com.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Phalen, William (2016). Coney Island : 150 years of rides, fires, floods, the rich, the poor and finally Robert Moses. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7864-9816-1. OCLC 933438460.

- 1 2 3 "American Experience. Coney Island. People & Events". PBS. Retrieved November 13, 2015.

- ↑ Berman, J.S.; Museum of the City of New York (2003). Coney Island. Portraits of America. Barnes and Noble Books. ISBN 978-0-7607-3887-0. Retrieved November 13, 2015.

- ↑

- "Travel". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, NY. June 9, 1864. p. 1.

- "Another New Rail Road". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, NY. June 9, 1864. p. 2.

- 1 2 3 "Brighton Beach History". Our Brooklyn. Brooklyn Public Library. August 30, 1936. Retrieved July 23, 2018.

- 1 2 Cudahy, B.J. (2009). How We Got to Coney Island: The Development of Mass Transportation in Brooklyn and Kings County. Fordham University Press. ISBN 978-0-8232-2211-7. Retrieved July 23, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Stanton, Jeffrey (1997). "Coney Island — Luxury Hotels". Coney Island History Site. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- ↑ Weinstein, Stephen (2000). "Brighton Beach". In Jackson, Kenneth T.; Keller, Lisa; Flood, Nancy. The Encyclopedia of New York City (2nd ed.). New York, NY, and New Haven, CT, USA: The New York Historical Society and Yale University Press. pp. 139–140. ISBN 0-300-11465-6. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

- ↑ "The Real Brighton Beach". The New Yorker. March 29, 2010. Retrieved July 23, 2018.

- ↑ Williams, Keith. "Brighton Beach: Old World mentality, New World reality". The Weekly Nabe. Retrieved July 29, 2012.

- ↑ "Engeman's New Bathing Hotel". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. July 1, 1878. p. 1. Retrieved July 23, 2018 – via Brooklyn Public Library; newspapers.com.

- 1 2 3 4 Feinman, Mark S. (February 17, 2001). "Early Rapid Transit in Brooklyn, 1878–1913". nycsubway.org. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- ↑ "ANOTHER CONEY ISLAND RAILROAD.; OPENING OF THE BROOKLYN AND FLATBUSH LINE TO BRIGHTON BEACH". The New York Times. July 2, 1878. Retrieved March 30, 2018.

- 1 2 3 "The Upper-Class Brooklyn Resorts of the Victorian Era". Curbed NY. June 27, 2013. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- ↑ "Wilderness Made Prosperous By One Man's Vision and Daring". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. July 11, 1954. p. 7. Retrieved July 23, 2018 – via Brooklyn Public Library; newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Opening Reception at the Oriental Hotel". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. August 3, 1880. p. 3. Retrieved July 23, 2018 – via Brooklyn Public Library; newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Obituary 1 -- No Title". July 13, 1906 – via query.nytimes.com.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Judith N. DeSena; Timothy Shortell (2012). The World in Brooklyn: Gentrification, Immigration, and Ethnic Politics in a Global City. Lexington Books. pp. 147–176. ISBN 978-0-7391-6670-3.

- ↑ David A. Sullivan. "Coney Island History: How 'West Brighton' became Modern-day Coney Island". heartofconeyisland.com. Retrieved November 19, 2016.

- ↑ "Sea Gate and Sheepshead". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. August 6, 1899. p. 16. Retrieved July 21, 2018 – via Brooklyn Public Library; newspapers.com.

- ↑ "QUEST FOR RURAL HOMES; Toilers of Greater New York to Gain by Long Island Rapid Transit. TWENTY MINUTES TO JAMAICA Pretty Suburban Villas Springing Up in Anticipation of the Proposed Atlantic Avenue Tunnel -Grass and Air for All". The New York Times. May 16, 1897. Retrieved July 23, 2018.

- ↑ J.B.T. (August 14, 1898). "SEA GATE". The New York Times. Retrieved July 23, 2018.

- ↑ "Coney - Carousel List". Westland Network. August 27, 1997. Retrieved November 13, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Immerso, Michael (2002). Coney Island: the people's playground (illustrated ed.). Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-3138-0.

- ↑ David A. Sullivan. "Coney Island History: The Elephant Hotel and Roller Coaster (1885-1896)". www.heartofconeyisland.com. Retrieved November 19, 2016.

- ↑ "Coney Island Blog - Coney Island History Project".

- 1 2 Matus, Paul. "The New BMT Coney Island Terminal". The Third Rail Online. Archived from the original on September 26, 2007. Retrieved August 29, 2007.

- ↑ "Canal Avenue, Brooklyn". January 12, 2016.

- ↑ JONAH OWEN LAMB (August 6, 2006). "The Ghost Ships of Coney Island Creek". The New York Times. Retrieved June 11, 2014.

- 1 2 Moses, Robert (1937). Improvement of Coney Island, Rockaway and South Beaches. Retrieved July 26, 2018 – via Internet Archive.

- 1 2 "Mayor Ready to Remodel Coney, Asks Moses for Revised Plan; Indicates He Favors Reconstruction of Resort on Broader Scale Than 1937 Proposal-- Says Demand for Recreation Has Changed Mayor for Broad Plan Mayor's Letter to Moses Held Up by Lack of Funds". The New York Times. June 25, 1939. Retrieved July 27, 2018.

- ↑ "CITY PLANS TO ADD 18 ACRES-TOCONEY; Purchase of Brighton Beach Tract and Extension of Boardwalk Proposed by Moses LAND TO COST $75,0001 Included in Price Also Are 173 Acres Under Water Off Plum Island as 'Protection' Wanted as Protection". The New York Times. August 5, 1938. Retrieved July 27, 2018.

- ↑ "HALF OF LUNA PARK DESTROYED BY FIRE AS 750,000 WATCH; Flames Sweep Over 8-Acre Area and Cause $500,000 Loss in 1 1/2-Hour Battle". The New York Times. August 13, 1944. Retrieved July 22, 2018.

- ↑ "Coney's OId Luna Park Will Yield To New Homes for 625 GI Families; LUNA PARK TO BOW TO HOMES FOR GI'S". The New York Times. August 18, 1946. Retrieved July 22, 2018.

- ↑ "NEW PARKING LOTS PLANNED BY MOSES; 25-Cent Fee Would Be Charged for Facilities at Coney Island and Rockaway Beach". The New York Times. August 18, 1949. Retrieved July 22, 2018.

- 1 2 "PUBLIC SEEN TIRING OF CONEY GIMMICKS; Moses Says People Are Turning to Places Like Jones Beach as Against 'Gadget' Resorts LONG BEACH 'A WARNING' Commissioner Advises Jersey Group Not to Commercialize Sandy Hook Project". The New York Times. October 6, 1949. Retrieved July 22, 2018.

- ↑ "STEEPLECHASE PIER PLAN; Closing in Summer Slated for $190,000 Rebuilding". The New York Times. April 7, 1949. Retrieved July 22, 2018.

- ↑ "Moses Asks Coney Island Rezoning To 'Upgrade' It as Residential Area; REZONING SOUGHT FOR CONEY ISLAND". The New York Times. April 2, 1953. Retrieved July 27, 2018.

- 1 2 3 Salerno, Al (October 24, 1954). "Break Ground for World's Greatest Aquarium at Coney Island". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. pp. 1, 21 – via Brooklyn Public Library; newspapers.com.

- ↑ "AMUSEMENT AREA IN CONEY EXEMPT; Estimate Board Votes Exclusion From Rezoning of a Section North of the Boardwalk". The New York Times. June 12, 1953. Retrieved July 27, 2018.

- ↑ Greenbaum, Clarence (June 12, 1953). "That Hot Dog Flavor To Remain at Coney". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. p. 1. Retrieved July 27, 2018 – via Brooklyn Public Library; newspapers.com.

- ↑ "CONEY EXTENSION DENIED TO MOSES; Estimate Board Rejects His Plan to Join Boardwalk With Manhattan Beach RESIDENTS PROTEST IT Their Willingness to Pay for Restoring Own Esplanade Spurs Unanimous Vote". The New York Times. September 23, 1955. Retrieved July 27, 2018.

- ↑ "PLANNERS OPPOSE HOUSING AT BEACH; Reject Proposal for Municipal Operation of Ex-G. I. Units -- Ask Quick Shift to Park WEIGH REZONING FOR TV N.B.C. Ties Favorable Vote on Flatbush Studio to Location of Its Color Operations". The New York Times. May 28, 1953. Retrieved July 27, 2018.

- ↑ Caro, R.A. (1974). The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York. A borzoi book. Alfred A. Knopf. Retrieved November 13, 2015.

- ↑ "PLAN OF AQUARIUM AT CONEY APPROVED; Estimate Board Appropriates $450,000 for First Stage -- Work Starts in Spring". The New York Times. October 23, 1953. Retrieved July 27, 2018.

- 1 2 Coney Girds for '55; Aquarium Progressing. Billboard. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. January 29, 1955. p. 63. Retrieved July 22, 2018.

- 1 2 "History of the New York Aquarium : NYC Parks". New York City Department of Parks & Recreation. May 31, 1934. Retrieved July 22, 2018.

- 1 2 3 Phillips, McCandlish (April 13, 1966). "Return of Coney Island; Amusement Area, Badly Hurt Last Year, Is Attempting to Win Back Customers". The New York Times. Retrieved July 30, 2018.

- ↑ "Coney Island Slump Grows Worse; Decline in Business Since the War Years Has Been Steady". The New York Times. July 2, 1964. Retrieved July 30, 2018.

- 1 2 Chan, Sewell. "Leaps of Imagination for the Parachute Jump", The New York Times, July 21, 2005. Accessed June 5, 2017. "In 1964 Steeplechase Park was demolished and the forlorn site became a symbol of blight, but the Parachute Jump remained a nostalgic touchstone."

- ↑ "Steeplechase Park Planned as the Site Of Housing Project". The New York Times. July 1, 1965. Retrieved July 30, 2018.

- ↑ Kaufman, Michael T. (March 19, 1964). "Housing and Amusements Give Coney Island a Dual Place in the Sun". The New York Times. Retrieved July 30, 2018.

- ↑ "6 Bikinied Beauties Attend Demolishing Of Coney Landmark". The New York Times. September 22, 1966. Retrieved July 30, 2018.

- ↑ "A 160-Foot-High Pleasure Dome Is Proposed for Coney Island; A DOME PROPOSED FOR CONEY ISLAND". The New York Times. July 24, 1966. Retrieved July 30, 2018.

- ↑ Fowle, Farnsworth (October 5, 1966). "City Wants Site of Steeplechase For Seafront Coney Island Park; Planning Board Sets Oct. 19 Hearing to Bar Area for High-Rise Homes". The New York Times. Retrieved July 30, 2018.

- ↑ Roberts, Steven V. (October 20, 1966). "A PARK IS BACKED FOR CONEY ISLAND; Developer Who Bought Site Calls Plan Wasteful". The New York Times. Retrieved July 30, 2018.

- ↑ Clark, Alfred E. (January 6, 1968). "State Is Urged to Build a Park At Coney Island's Steeplechase". The New York Times. Retrieved July 30, 2018.

- ↑ Bennett, Charles G. (May 23, 1968). "PARK USAGE VOTED FOR STEEPLECHASE; City to Seek $2-Million Aid to Buy Coney Island Tract". The New York Times. Retrieved July 30, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Fowler, Glenn (June 3, 1979). "15‐Year Dispute Over Lease for Coney Island Steeplechase Continues". The New York Times. Retrieved September 15, 2018.

- 1 2 3 Carmody, Deirdre (August 5, 1985). "REBORN STEEPLECHASE PARK PLANNED AT CONEY I." The New York Times. Retrieved September 16, 2018.

- 1 2 Chambers, Marcia (April 3, 1977). "New York, After 10 Years, Finds Plan to Create a Coney Island Park Is Unsuccessful". The New York Times. Retrieved September 15, 2018.

- ↑ "Video & Photos of the Day: Riding Coney Island's Abandoned Giant Slide (1973)". February 8, 2015.

- ↑ "Aquarium Urges Razing Of Coney Island Cyclone". The New York Times. May 27, 1975. Retrieved September 15, 2018.

- ↑ Futrell, J. (2006). Amusement Parks of New York. Amusement Parks Series. Stackpole Books. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-8117-3262-8. Retrieved September 15, 2018.

- ↑ "Parachute Jump at Coney Island Loses Chance of Landmark Status". The New York Times. October 21, 1977. Retrieved September 15, 2018.

- ↑ Chambers, Marcia (June 16, 1977). "City, in a Shift, Says Coney I. Park Should Become Amusement Area". The New York Times. Retrieved September 15, 2018.

- 1 2 Campbell, Colin (August 29, 1981). "BELEAGUERED CONEY ISLANDERS RALLY WITH SENSE OF AFFECTION; The Talk of Coney Island". The New York Times. Retrieved September 16, 2018.

- ↑ Lynn, Frank (April 6, 1979). "Koch Urges City Be Considered As a Site for Gambling Casinos". The New York Times. Retrieved September 16, 2018.

- ↑ Lynn, Frank (July 19, 1979). "Koch Puts Price On City Support For Casino Vote". The New York Times. Retrieved September 16, 2018.

- ↑ Basler, Barbara (August 14, 1979). "Opinions Mixed On Casino Plan In Coney Island". The New York Times. Retrieved September 15, 2018.

- ↑ Rangel, Jesus (March 29, 1986). "CONEY I. OPENING SEASON WITH HOPE". The New York Times. Retrieved September 16, 2018.

- ↑ Rangel, Jesus (December 5, 1986). "STATE PROPOSES BASEBALL STADIUM FOR CONEY I." The New York Times. Retrieved September 16, 2018.

- ↑ Farrell, Bill (January 21, 1998). "Baseball Pitch Back in Sportsplex Mix Rally for Coney Venue". NY Daily News. Retrieved November 13, 2015.

- ↑ Martin, Douglas (November 23, 1998). "Back to the Drawing Board in Coney Island". The New York Times. Retrieved November 13, 2015.

- 1 2 "Mayor Bloomberg Announces Strategic Plan For Future of Coney Island". NYCEDC. September 14, 2005. Retrieved July 21, 2018.

- ↑ Fung, Amanda (June 28, 2009). "Coney Island keeper". Crain's New York Business. Retrieved November 14, 2015.

- ↑ 1.5 Billion Development Plan For Coney Island Publication: The New York Sun Date: November 13, 2006

- ↑ "Imagineconey". Imagineconey. Retrieved August 13, 2012.

- ↑ "New York City Department of City Planning — Amanda M. Burden, Director". Nyc.gov. Retrieved August 13, 2012.

- ↑ "Coney Island amusement park closing: News & Videos about Coney Island amusement park closing — CNN iReport". Ireport.com. Retrieved March 17, 2010.

- ↑ "Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (ULURP) – New York City Department of City Planning". Nyc.gov. Archived from the original on July 19, 2012. Retrieved August 13, 2012.

- ↑ See Bloomberg News, November 29, 2006.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on July 17, 2012. Retrieved June 13, 2013.

- ↑ "Plans Coming Together For Coney Island Amusement Park Expansion" Archived October 8, 2007, at the Wayback Machine., NY1, November 14, 2006

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on July 3, 2009. Retrieved June 17, 2009. Planning Commission Approves Unloved Coney Plan: The Village Voice: 6/17/09

- ↑ Calder, Rich (September 5, 2007). "Ride Over for Coney Classics". New York Post. Retrieved September 5, 2007.

- ↑ "Coney Island gets first new roller coasters in 80 years". Reuters.

- ↑ Brown, Stephen R. (June 14, 2014). "Coney Island's new Thunderbolt roller coaster officially opens". NY Daily News. Retrieved June 29, 2014.

- ↑ Nathan's to recover Brooklyn Daily

- ↑ "Despite Sandy's Wrath, Coney Island's Luna Park To Reopen On Schedule Sunday". CBS News New York. Retrieved March 22, 2013.

- ↑ Schneider, Katy (June 28, 2018). "What to Know About the New York Aquarium's New Shark Building". Daily Intelligencer. Retrieved June 29, 2018.

- ↑ Hodgson, Sam (June 28, 2018). "Coney Island's Newest Wonder: Sharkitecture!". New York Times official website. Retrieved July 1, 2018.

- ↑ "Log flume ride, zip lines coming to Coney Island". am New York. August 23, 2018. Retrieved August 24, 2018.

- 1 2 Chung, Jen (August 23, 2018). "Coney Island's Luna Park Is Getting Log Flume Ride, A Ropes Course, And More!". Gothamist. Archived from the original on August 23, 2018. Retrieved August 24, 2018.

- ↑ "City Unveils Plans For New Water Park, Arcade On Coney Island". CBS New York. August 23, 2018. Retrieved August 24, 2018.

- ↑ Ramirez, Jeanine (August 21, 2018). "Coney Island could see first new hotel in over 50 years". Spectrum News NY1 | New York City. Retrieved August 24, 2018.

- ↑ Franklin, Sydney (August 21, 2018). "Shore Theater on Coney Island will be converted into a boutique hotel". Archpaper.com. Retrieved August 24, 2018.

- ↑ "Locals demand beloved Coney ice rink remain under Parks Department control". Brooklyn Daily. August 31, 2018. Retrieved September 15, 2018.

- ↑ "Deno's Wonder Wheel". Archived from the original on October 20, 2017. Retrieved August 28, 2018.

- ↑ NYCEDC Announces New "Thunderbolt" Roller Coaster to be Built at Coney Island Archived March 11, 2014, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Marden, Duane. "Thunderbolt (Luna Park)". Roller Coaster DataBase. Retrieved November 16, 2013.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on March 11, 2014. Retrieved June 4, 2014. luna-park-breaks-ground-on-new-roller-coaster-the-thunderbolt-on-coney-island

- ↑ New Roller Coaster Promises Coney Island a Return of Thrills

- ↑ coney-islands-luna-park-to-get-new-roller-coaster

- ↑ Brown, Stephen R. (June 14, 2014). "Coney Island's new Thunderbolt roller coaster officially opens". NY Daily News. Retrieved June 29, 2014.

- ↑ Foderaro, Lisa W. (May 24, 2013). "B&B Carousell Horses Return Home to Coney Island". The New York Times. Retrieved July 28, 2018.

- ↑ "Coney Island's B&B Carousell placed on National Register of Historic Places". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. July 28, 2018. Retrieved July 28, 2018.

- ↑ "B&B Carousell designated national historic place, up for federal preservation money • Brooklyn Daily". Brooklyn Daily. March 11, 2016. Retrieved July 28, 2018.

- ↑ "Roller Coasters, Theme Parks, Thrill Rides".

- 1 2 Barbara La Rocco, Going Coastal New York City, Going Coastal, Inc., 2004, page 137.