Barren Island, Brooklyn

Coordinates: 40°35′34″N 73°53′35″W / 40.59278°N 73.89306°W

Barren Island is a former island in Jamaica Bay, off the southeast shore of Brooklyn in southern New York City, New York. It was originally part of a Lenape Native American land before being settled in the 17th century. Barren Island, whose name is a corruption of a Dutch word for bears, was geographically part of the outer barrier island group on the South Shore of Long Island. The former island is separated from the Rockaway Peninsula in Queens by the Rockaway Inlet.

The island was sparsely inhabited before the 19th century, owing mainly to its isolated location away from the rest of the city. From the 1850s to the mid-1930s, Barren Island was developed as an industrial complex. Barren Island once maintained a somewhat diverse community for its time, and at its peak housed 1,500 residents. The community was originally supported by fish rendering plants and other industries related to offal products. The island housed a plant that received the carcasses of the city's dead horses and turned them into a variety of industrial products, including glue, fertilizer, buttons, and materials for refining gold and sugar.[1] This activity inspired the name Dead Horse Bay for the still extant body of water on the western shore.

Starting in the 1890s, Barren Island was also home to a waste processing plant. The odor from the plant was so noxious that they could be smelled from miles away. In 1916, a controversy arose when the city tried to relocate the waste processing plant away from Barren Island to Staten Island. As a result, operations on Barren Island continued until 1921. By the 1920s, most of the industrial activity had tapered off.

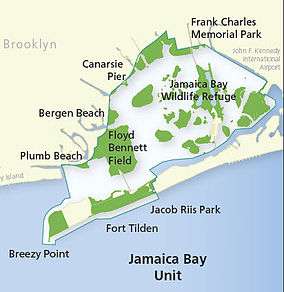

In the 1920s, landfill was used to unite the island with the rest of Brooklyn for what became Floyd Bennett Field. Most of the residents were evicted, but a few were allowed to stay until 1942. No trace remains of the former island's industrial use. All of what was once Barren Island is now part of the Jamaica Bay Unit of Gateway National Recreation Area, managed by the National Park Service.

Name

The area was originally the homeland of the Canarsie Indians, a group of Lenape Native Americans. The Indians referred to the archipelago of islands near Barren Island by a name alternatively transcribed as "Equandito", "Equendito", or "Equindito", which means "Broken Lands".[2][3] This name also applied to several smaller islands in the area, such as Mill Island.[4] Throughout its existence, Barren Island has also been referred to as "Broken Lands" in English, as well as "Bearn Island", "Barn Island", and "Bear's Island".[5] The name "Barren Island" is a corruption of "Beeren Eylandt", a Dutch name that means "Bears' Island".[6][3][7] It does not relate to the English word describing the geography of the island,[7] although the name does fit the geography.[6]

Geography and ecology

Barren Island was originally part of an estuary at the mouth of Jamaica Bay, and served mainly as a barrier island for the larger Long Island, located to Barren Island's north. The bay, in turn, was created during the end of the Wisconsin glaciation.[8] The glacier's edge had been in the middle of Long Island, creating a series of hills across the island, and the water from the melting glacier ran downhill toward a low-lying delta that adjoined the Atlantic Ocean. This delta became Jamaica Bay.[9] A body of water called Rockaway Inlet, located south of the island, connected the bay with the ocean.[10] By the late 17th century, the island had 70 acres (28 ha) of salt meadows and 30 acres (12 ha) of uplands.[5] The island also had cedar forests.[3] Salt and reed grasses, as well as hay, served as food for early settlers' livestock.[11][12]

Barren Island's geography was significantly altered in the 19th century due to shifting tides and storms.[13] The island was part of the outer barrier, a series of barrier islands along the southern shore of Long Island, which includes Fire Island and formerly included the Rockaway Peninsula. Barren Island, the Rockaways, Pelican Beach, and Plumb Beach were originally separate barrier islands protecting Jamaica Bay.[9] In 1818, Barren Island had dunes and scattered trees.[14] By 1839, Barren Island, Plumb Beach, and Pelican Beach were a single island, separated from Coney Island to the west by Plumb Beach Inlet. By the end of the century, Gerritsen Inlet had formed between Barren Island and Plumb and Pelican Beaches.[9]

The neighboring island of Rockaway Beach, now part of the Rockaway Peninsula, also had a large impact on Barren Island's geography. Originally, Rockaway Beach was located to Barren Island's east, and the two islands' tips were aligned.[9][15] However, starting in the mid-19th century, Rockaway Beach was extended more than one mile to the southwest due to the construction of several jetties to protect manmade developments on that island.[15] This caused changes to Barren Island's ecology.[13] In the early 20th century, Barren Island consisted of sand dunes on the coasts and salt marshes inland.[16] However, the extension of Rockaway Beach meant that Barren Island was no longer a barrier island, and so the beach on Barren Island was washed away.[13]

By the late 1920s, the now-1,300-acre (530 ha) Barren Island's eastern side had been transformed due to industrial development there, with a small patch of dunes remaining. The western side of the island, containing dunes, woods, and wetlands, was largely untouched. The island's southern coast contained a tidal creek stretching into the center of the island, where the tidal wetlands remained mostly intact. The wetlands were abutted by the man-made Mill Basin to the north. Tidal creeks also stretched across the island's marshes, although one of these creeks had been bisected by the construction of Flatbush Avenue in 1925. The water adjoining the island's northern and western coasts was heavily polluted.[17] The entirety of the former island, which is now a peninsula, is now the site of Floyd Bennett Field,[18][19] which in turn is part of the Gateway National Recreation Area.[20]

History

Settlement

Originally, the area around Barren Island was settled by the Lenape. According to a 2009 study by the State University of New York, historians believe that the Canarsie Indians who occupied the area used Barren Island to fish.[2] In 1636, as Dutch New Netherland was expanding outward from present-day Manhattan, Dutch settlers founded the town of Achtervelt (later Amersfoort) and purchased 15,000 acres (6,100 ha) around Jamaica Bay north of Barren Island. Amersfoort was centered around the present-day intersection of Flatbush Avenue and Flatlands Avenue, approximately 2 miles (3.2 km) northwest of Barren Island.[21] In 1664, New Netherland became British New York and Amersfoort was renamed Flatlands.[12][21] The island, as well as nearby Mill Basin, was sold to John Tilton Jr. and Samuel Spicer that year.[22]

Canarsie Indian leaders had signed 22 land agreements with Dutch settlers by 1684. These agreements handed ownership of much of their historic land, including Barren Island, to the Dutch.[23][12] Barren Island was one of the first barrier islands to be settled because it was easily accessible. At low tide, people on "mainland" Brooklyn could walk across a shallow stream, while at high tide, small craft could access the northern coast while larger craft could dock on the southern coast.[5]

Barren Island, as well as nearby Mill Island and Bergen Island, were part of the Town of Flatlands. By the 1670s, all three islands were leased by a settler named Elbert Elbertse.[24] Records from 1679 indicate that Elbertse had complained that other settlers were going to Barren Island to let their horses graze on his land. The settler William Moore started digging sand from the island in the 1740s. In 1762, Moore characterized the island as "vacant and unoccupied".[5] It remained as such until the end of that century, being used mainly as a grazing field.[25] Even during the first half of the 19th century, the island had few residents.[5] Around c. 1800, a man named Dooley established an inn and entertainment venue for fishermen and hunters on the east side of Barren Island;[25][3] the house's ownership later passed to the Johnson family. Two more residences were built on the island before 1860, for the Skidmore and Cherry families. Maps from that time do not show any other man-made structures on Barren Island.[26]

The National Park Service states that "a pirate named Gibbs" might have buried treasure on the island c. 1830.[27] According to another account, "only part of [the treasure] was recovered".[28]

Fish-oil and fertilizer plants

The presence of the naturally deep Rockaway Inlet, combined with the remoteness of Barren Island from the rest of the developed city, made the island suitable for industrial uses.[14] An isolated settlement[29] on the island was developed in the late 19th century.[8] From 1859 to 1934, approximately 26 industries would open facilities on Barren Island, mostly on the eastern and southern coasts.[30] Few industrial sectors were enticed to move to Barren Island, precisely because of its isolation: there were no direct land routes to the rest of the city.[14] Waste management was the sole industry for which Barren Island was an ideal location, and as a result, waste processors made up most of the industries that were established on Barren Island.[31]

The island's first main industrial use was for fish rendering plants, as well as for "fertilizer plants" that processed offal products.[30][32] The fish rendering plants processed schools of menhaden, a type of fish that was caught off the coast of Long Island, and turned them into fish oil or scraps.[33][31] Meanwhile, the fertilizer plants turned horse bones into glue,[32] processing almost 20,000 horse corpses annually at one point. This activity inspired the name Dead Horse Bay for the still extant water body on the western shore,[34] since the waste processors on the island would simply dump the processed waste into that bay.[31] By the late 1850s, two fertilizer plants had been built on the island, but their existence was short-lived.[35] One plant on the eastern shore was operated by Lefferts R. Cornell and processed animal corpses. Cornell's plant was destroyed by fire in 1861, and he moved his factory to Flatbush.[30] The other plant on the western shore, which was operated by William B. Reynolds and performed a similar function to the Cornell plant, simply ceased operations.[36] Before these fertilizer plants had opened, the town of Flatlands did not impose any property taxes on buildings located on Barren Island. The first property tax assessments for the island were for these factory buildings.[30]

In 1861, ownership of part of the island passed to a person named Francis Swift. However, he did not immediately develop his land.[37] No new factories were developed until at least 1868, when Smith & Co. opened a 45-acre (18 ha) fish-processing factory. Steinfield and Company also operated a factory from 1869 to 1873, but it is unknown what the factory was used for. A person named Simpson opened a factory on Barren Island in 1870, but that factory had closed by 1872.[36] Swift and E. P. White also created their own fertilizer factory in 1872, and it remained until the 1930s.[36][31] A factory belonging to the Products Manufacturing Company, located where Flatbush Avenue is now, was reportedly the world's largest carcass-processing plant.[31] Through the 1870s, eight more factories opened on the island, of which two had ephemeral existences.[36] Barren Island's factories, which were vulnerable to landslides, fires, or waves from high-tide, typically lasted for only fleeting periods of time.[38] White's factory burned down in 1878, but was rebuilt soon afterward.[33] In 1883, the oil factories hired a combined 350 men and collectively used 10 steamships.[39]

The waste-processing factories on Barren Island gave rise to a small but thriving community, which was clustered on the island's southeastern coast.[38] In a census conducted by the town of Flatlands in 1870, it was noted than 24 people, all single men who had immigrated from Europe, lived in a single residence and likely worked at an oil factory on Barren Island.[36] A subsequent census in 1880 counted six "households" that were entirely composed of single men, as well as 17 families.[40][38] There were a total of 309 people residing on the island that year.[41][38] By that year, the island had three fish oil factories and four fertilizer plants.[33] The development of Barren Island continued in tandem with the population growth: in 1878, there were six large structures on the island's southern and eastern coasts, as opposed to the single hotel that had been reported in the 1852 map.[42] By 1884, five hundred people worked on the island.[27] The 1892 census recorded four large "clusters" of laborers from the same countries who resided in the same households on Barren Island.[41]

In 1891, the Rockaway Park Improvement Company complained that the "offensive" smells from Barren Island was ruining the quality of life for vacationers in the Rockaways, located across the Rockaway Inlet from Barren Island. Following this complaint, New York State Health Board composed a report about the status of the industries on Barren Island.[43] Subsequently, New York Governor David B. Hill declared four companies to be "public nuisances". He ordered twice-weekly inspections of the offending factories to ensure that the companies complied with health regulations.[44]

Garbage processing

By the 1890s, there had been a steep decline in the number of menhaden off Long Island. That, along with the Panic of 1893, caused the closure of the fish-oil plants.[45][46] However, the carcass-dumping continued: in one five-day span in August 1896, records show that 1,256 horse carcasses had been processed.[46][47] That year, the city awarded the New York Sanitary Utilization Company a $1 million contract to operate on Barren Island,[47] having unsuccessfully attempted to bury waste in Rikers Island.[46] The company, which collected garbage from hotels around the city,[46] operated a garbage incinerator[47] that turned New York City's waste into fertilizer, grease, and soap.[48][46] Residents of nearby Brooklyn communities opposed the construction of the incinerator, but to no avail.[49] By 1897, the island was home to two garbage plants and four animal-processing plants.[50]

Barren Island soon became known for its use as a garbage dump. Waste and animal carcasses from Brooklyn, Manhattan, and the Bronx was sent to Barren Island, while New York City's other two boroughs, Queens and Staten Island, had their own garbage disposal sites.[7] The Sanitary Utilization Company disposed of glass bottles and other non-processable items on the northern coast of Barren Island.[51] Some valuable trash, such as jewelry, also ended up on Barren Island.[34] The island's residents did not mind the smell of the processed garbage.[52] However, the incinerator's scents were so noxious that residents on "mainland" Brooklyn, 4 miles (6.4 km) away, could not stand the odors.[3][48] In 1899, state and city lawmakers passed bills to reduce the stench,[53] but these bills died because the governor and mayor opposed these actions.[54][52] The incinerator was damaged by fire in 1904.[42] A major fire two years later caused $1.5 million in damage after 16 buildings burned down.[55] The unstable land along the coast also caused up to five instances of landfall from 1890 to 1907, which damaged factories on the island.[42]

By the 1900s, the island was receiving seven or eight fully loaded garbage scows every day, which delivered 50 to 100 tons of trash. A boat of dead horses, cats, cows, and other animals also made daily deliveries at Barren Island. Workers at the horse processing factories were paid more than those at the garbage incinerator.[56] As of the 1900 census, there were 520 Barren Island residents in 103 households, and all of the large "households" of male laborers had been dispersed.[57][58] Around this time, there were four main landowners: the Sanitary Utilization Company, the Roman Catholic Diocese of Rockville Centre, the government of Kings County (Brooklyn), and the Products Manufacturing Company.[59]

Barren Island also served as a residential community for the families of laborers who worked there, and at its peak in the 1910s, it was home to an estimated 1,500 people.[30][7][52] Most of these residents were either African-American laborers or immigrants from Italy, Ireland, or Poland, since few Americans were willing to work with the garbage-related industries that were present on Barren Island.[7] Despite the racial differences, the island's residents coexisted relatively peacefully, as opposed to the rest of the United States were racial strife was high.[34] The island had a public school, a church, a post office, a New York City Police Department precinct, hotels and inns, various stores and saloons, and three ferry routes to other Brooklyn neighborhoods.[57][59] A "Main Street" stretched horizontally across Barren Island, lined with buildings that faced south toward Rockaway Inlet. The street grid in the island's central section was built haphazardly, based possibly on sand dune patterns.[59] A caste system was used to divide the different types of workers who worked on the island: "rag pickers" were at the bottom of the hierarchy, followed by metal-and-paper scavengers, then bone sorters.[7] Students who lived on Barren Island were dismissed from school early so they can help their parents scavenge.[60] The island's African-American residents were considered to be part of the lowest class.[7] Some farmers also resided on Barren Island.[59] The island had no running water, sewage treatment, or New York City Fire Department stations, making it an inhospitable place to reside in.[48] An 1897 article in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle described pools of sewage around the school buildings and on the island's main street, as well as accumulations of trash scattered haphazardly across the island, and noted that "how any person manages to work on the island is a mystery".[50]

Through the 1910s, as the smells got worse, residents filed more complaints with the city, and real estate developers in nearby communities such as the Rockaways and Flatlands cajoled the city government to take action.[58] Residents in nearby neighborhoods blamed their illnesses on the smells,[34] and one group from Neponsit, Queens, claimed that 750,000 residents in a 8-mile (13 km) radius were subject to the odors emanating from Barren Island.[61] In 1916, New York City Mayor John Purroy Mitchel announced that a new garbage landfill would be built on Staten Island to replace the Barren Island landfill. Due to complaints from Staten Islanders, the location of the landfill was changed several times.[62] The city eventually decided to build the landfill in Fresh Kills, an isolated plain far away from the vast majority of the island's residents. It had overruled several injunctions and formal complaints from Staten Island residents who did not want a landfill anywhere in the borough.[63] Politicians from the Democratic Party accused Mitchel, a Republican Party member, of corruption. Mayoral candidate John Hylan said that if elected in the upcoming year's mayoral election, he would relocate the landfill off Staten Island.[64] Hylan ultimately won the election against Mitchel, and he threatened to revoke the Fresh Kills landfill operator's license. Hylan ultimately restored dumping operations at Barren Island, despite denying rumors that stated the same. After political backlash, the city started paying $1,000 per day to the Sanitary Utilization Company.[62]

The city started dumping its trash into the ocean in 1919, and the Sanitary Utilization Company closed its facility two years later.[62] Additionally, the advent of automobile travel reduced horse-drawn travel in New York City, resulting in fewer horse cadavers being processed on Barren Island. By 1918, the island processed 600 horse carcasses per year; it had once processed the same number of corpses in 12 days.[65][54] The Thomas F. White Company closed the E. P. White fertilizer factory by around 1921 and started demolishing the Sanitary Utilization Company facility around the same time.[66] The final horse processing plant closed in 1921.[65] The last garbage processing plant on Barren Island, the Products Manufacturing Company, was transferred to city ownership in 1933, and the city closed it down two years later.[41]

Seaport plans and decline of community

As early as 1910, developers began dredging ports within Jamaica Bay in an effort to develop a seaport district there.[67][51] Although the city allowed several piers to be constructed in 1918, only one was built. The pier, which was built in order to receive landfill for the other proposed piers, stretched 1 mile (1.6 km) northeast and was 700 feet (210 m) wide.[68]

By the 1920s, a small percentage of residents remained on the island, as did two factories.[18][48] A municipal ferry service to the Rockaway Peninsula and an extension of Flatbush Avenue were both opened in 1925.[69][70] The new modes of transportation were part of a proposal to develop Barren Island as a seaport. The creeks along Barren Island's coast were to be turned into canals, and the city had bought the western part of the island for use as parkland.[70] The new transport options provided some short-term benefits for the remaining residents, who could go to "mainland" Brooklyn to work and shop. Residents of "mainland" Brooklyn could also go to the Rockaway beaches by driving to the end of Barren Island and taking the ferry.[71] By 1928, many of the buildings were abandoned, but the public school and church remained.[72] In 1931, the city took possession of 58 acres (23 ha) on the western side of the island, which comprised much of Main Street and the structures on the island's southwestern side. That plot was combined with a 110-acre (45 ha) tract owned by Kings County to create Marine Park.[73]

During Barren Island's final years, a teacher named Jane F. Shaw (whom the press nicknamed "Angel of Barren Island" and "Lady Jane") took a job at the island's public school.[27] Shaw eventually became the principal and lobbied on behalf of the island, persuading Senator Robert F. Wagner to rename the island "South Flatlands" in order to integrate it with the city. After a census in 1930 neglected to count Barren Island residents, Shaw cajoled the United States Census Bureau into counting the island's remaining 416 residents.[65] When New York City Parks Commissioner Robert Moses ordered the eviction of all residents in early 1936, Shaw persuaded him to move the eviction date to the end of June, so her students could complete their school year.[74]

Airport and park use

In 1927, a pilot named Paul Rizzo opened the Barren Island Airport, a private airstrip, on the island.[75][65] The next year, the city's aeronautic engineer Clarence Chamberlin chose Barren Island as the site for the city's new municipal airport, which would become Floyd Bennett Field.[76][77] The New York City Department of Docks was in charge of constructing the Barren Island Airport.[19] A contract for the airport's construction, awarded in May 1928, entailed filling in or leveling 4,450,000 cubic yards (3,400,000 m3) of soil across a 350-acre (140 ha) parcel. Sand from Jamaica Bay was used to connect Barren Island and adjacent islands, as well as raise the site to 16 feet (4.9 m) above the high–tide mark. This contract was completed by May 1929. A subsequent contract involved filling in an extra 833,000 cubic yards (637,000 m3) of land.[18][19] Floyd Bennett Field was formally completed on May 23, 1931.[78][79][80] Around this time, about 400 people still lived on the island.[57][65][52]

Robert Moses expanded Marine Park in 1935, and the city acquired 1,822 acres (737 ha) of land. This comprised the entire island west of Flatbush Avenue.[81] In spring 1936, Moses attempted to evict the remaining Barren Island residents, but they simply moved to a still-occupied portion of the island.[65][52] At the time, 25 people still lived on a 90-acre (36 ha) spit at the southern end of the island.[81][52] In 1937, Flatbush Avenue was extended south to the Marine Parkway–Gil Hodges Memorial Bridge, which in turn connected to the Rockaways and Jacob Riis Park. The opening of the Marine Parkway Bridge marked the end of Barren Island's isolated status.[81][82]

In 1941, Bennett Field was taken over by the United States Navy and converted to Naval Air Station New York.[83][84] The next year, the Navy expanded the airport's facilities to the southern tip of Barren Island, forcing the former island's last residents to move out.[85][65][86] During its wartime upgrade of Bennett Field, the Navy burned and cleared all remaining structures on Barren Island, as well as eliminated its original landscape.[87] No trace of the island remains,[7] as it has been totally subsumed by Bennett Field.[3]

In the 1950s, Moses attempted to expand the former island, by then a peninsula, to the west using garbage covered by topsoil. However, the layer of soil has since eroded, and garbage can be seen on the coast during low tide.[34] This coast contains many exposed broken glass bottles and other non-biodegradable material.[88][89]

In popular culture

Barren Island by Carol Zoref is a novel about an Eastern European immigrant family's experiences on the island. It was placed on the 2017 National Book Award for Fiction "longlist" and has won the Association of Writers & Writing Programs' 2015 Award Series.[90][91]

References

- ↑ "Barren Island". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. April 24, 1856. p. 2. Retrieved April 22, 2018 – via Brooklyn Public Library; newspapers.com.

- 1 2 Cody 2009, p. 19.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Seitz & Miller 2011, p. 257.

- ↑ "Lindower Park Highlights : NYC Parks". New York City Department of Parks & Recreation. Retrieved January 20, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Black 1981, p. 14.

- 1 2 Cody 2009, p. 22.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Johnson, Kirk (November 7, 2000). "All the Dead Horses, Next Door; Bittersweet Memories of the City's Island of Garbage". The New York Times. Retrieved January 6, 2018.

- 1 2 Cody 2009, p. 15.

- 1 2 3 4 Cody 2009, p. 16.

- ↑ Brooklyn, NY Quadrangle (Map). 1:62,500. 15 Minute Series (Topographic). United States Geological Survey. 1898. § SW. Retrieved February 13, 2010.

- ↑ Black 1981, p. 13.

- 1 2 3 Cody 2009, p. 20.

- 1 2 3 Cody 2009, p. 17.

- 1 2 3 Cody 2009, p. 24.

- 1 2 Frank, Dave (March 30, 2001). "Geology of National Parks". Geology of National Parks. Retrieved January 6, 2018.

- ↑ Cody 2009, p. 18.

- ↑ Cody 2009, p. 35.

- 1 2 3 Historic Structure Report Volume 1 1981, p. 13.

- 1 2 3 Wrenn 1975, p. 18.

- ↑ "North Shore District". National Park Service. Jamaica Bay Institute. Retrieved February 13, 2010.

- 1 2 Black 1981, p. 9.

- ↑ Ross, Peter (1902). A History of Long Island, Vol. 1. Jazzybee Verlag. p. 37. ISBN 9783849679248.

- ↑ Liff, Bob (November 26, 1998). "FOR INDIANS, DEEDS LED TO END OF ERA". NY Daily News. Retrieved January 25, 2018.

- ↑ Black 1981, p. 11.

- 1 2 Cody 2009, p. 23.

- ↑ Black 1981, pp. 14–15.

- 1 2 3 National Park Service (1979). Gateway National Recreation Area (N.R.A.), General Management Plan (GMP) (NY,NJ): Environmental Impact Statement. Gateway National Recreation Area (N.R.A.), General Management Plan (GMP) (NY,NJ): Environmental Impact Statement. p. 108. Retrieved January 17, 2018.

- ↑ Thompson, B.F. (1839). History of Long Island: Containing an Account of the Discovery and Settlement; with Other Important and Interesting Matters to the Present Time. Cornell Library New York State Historical Literature. E. French. p. 450. Retrieved January 17, 2018.

- ↑ Historic Structure Report Volume 1 1981, p. 10.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Black 1981, p. 25.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Cody 2009, p. 25.

- 1 2 Feuer, Alan (July 29, 2011). "Jamaica Bay: Wilderness on the Edge". The New York Times. Retrieved July 29, 2011.

- 1 2 3 Black 1981, p. 27.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Williams, Keith (July 6, 2017). "When Dead Horse Bay Was True to Its Name". The New York Times. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- ↑ Black 1981, p. 15.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Black 1981, p. 26.

- ↑ Dubois 1884, p. 78.

- 1 2 3 4 Cody 2009, p. 26.

- ↑ Dubois 1884, p. 79.

- ↑ Black 1981, pp. 26–27.

- 1 2 3 Black 1981, p. 32.

- 1 2 3 Black 1981, p. 30.

- ↑ "Barren Island; The State Health Board Reports Upon Its Industries". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. January 30, 1891. p. 1. Retrieved April 22, 2018 – via Brooklyn Public Library; newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Barren Island Nuances.; Gov. Hill Orders the State Health Board to Supervise Them" (PDF). The New York Times. May 15, 1891. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 9, 2018.

- ↑ Black 1981, p. 28.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Seitz & Miller 2011, p. 260.

- 1 2 3 "TO USE NEW-YORK GARBAGE; THE PLANT ON BARREN ISLAND WILL SOON BE FINISHED. The Contracting Company Headed by "Dave" Martin, the Philadelphia Politician – From the Garbage It Will Extract Valuable Oil and Matter for Fertilizers – The Latest Method Will Be Used – Position of Barren Islands and the Works" (PDF). The New York Times. September 27, 1896. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Schneider, Daniel B. (July 18, 1999). "F.Y.I.". The New York Times. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ↑ "Will Fight a Garbage Plant". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. June 10, 1896. p. 1. Retrieved April 22, 2018 – via Brooklyn Public Library; newspapers.com.

- 1 2 "To Clean Barren Island". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. September 17, 1897. p. 4. Retrieved April 22, 2018 – via Brooklyn Public Library; newspapers.com.

- 1 2 Cody 2009, p. 29.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "BARREN ISLAND IS FADING; Marine Park Squeezing Out Community On the Sand Dunes in Jamaica Bay" (PDF). The New York Times. February 19, 1939. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ↑ "BARREN ISLAND NUISANCE.; Senate Acts Favorably on a Bill Virtually Removing It" (PDF). The New York Times. April 5, 1899. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 9, 2018.

- 1 2 Black 1981, p. 31.

- ↑ "$1,500,000 FIRE LOSS ON BARREN ISLAND; 16 Structures Go – Flames Not Checked Early To-day. REFUSE PLANTS DESTROYED 600 Families Flee In Boats to the Mainland – The Plants Moy Not Be Rebuilt on the Island" (PDF). The New York Times. May 21, 1906. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ↑ Black 1981, p. 20.

- 1 2 3 Black 1981, p. 33.

- 1 2 Cody 2009, p. 27.

- 1 2 3 4 Cody 2009, p. 28.

- ↑ "Good Work of School on Barren Island". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. August 18, 1901. p. 7. Retrieved January 7, 2018 – via Brooklyn Public Library; newspapers.com.

- ↑ "WILL CONTINUE WAR ON BARREN ISLAND; Residents of Neponsit Plan Meeting to Further Campaign Against Disposal Plants. AWAIT REPORT BY EXPERT Representative of Complainants Against Odors of Garbage Says 750,000 Are Suffering" (PDF). The New York Times. November 6, 1915. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- 1 2 3 Seitz & Miller 2011, p. 262.

- ↑ "GARBAGE DISPOSAL GOES TO RICHMOND; One Injunction Vacated and Second Reached Board of Estimate Too Late. TO BUILD PLANT AT ONCE Staten Island Residents' Protests of No Avail – City Will Save $1,000,000, Mayor Mitchel Says" (PDF). The New York Times. April 11, 1916. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ↑ "HYLAN MAKES ISSUE OF RICHMOND GARBAGE; Promises to Attack Disposal Plant Contract, if Elected, and to Cut Ferry Fares" (PDF). The New York Times. October 28, 1917. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Seitz & Miller 2011, p. 263.

- ↑ Cody 2009, p. 31.

- ↑ "Marine Park Highlights". New York City Department of Parks & Recreation. June 17, 2003. Retrieved January 6, 2018.

- ↑ Black 1981, pp. 77–79.

- ↑ "ROCKAWAY FERRY OPENED BY HYLAN; Other City Officials Also Mark Start of Line From Barren Island to Riis Park. ONE FERRYBOAT STRANDED Laden With Women and Children, It Is Held on Sand Bar for Half an Hour" (PDF). The New York Times. October 18, 1925. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- 1 2 Cody 2009, p. 32.

- ↑ Cody 2009, p. 33.

- ↑ Cody 2009, p. 36.

- ↑ Cody 2009, p. 51.

- ↑ "Miss Jane Shaw Will Retire as Fairy God Mother, Barren Island". Daily Messenger. Canandaigua, N.Y. July 24, 1936. p. 8. Retrieved April 22, 2018 – via newspapers.com.

- ↑ Cody 2009, p. 34.

- ↑ "Airport Catches Chamberlin's Eye" (PDF). New York Evening Post. June 3, 1928. p. 2. Retrieved December 15, 2017 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ Wrenn 1975, p. 17.

- ↑ Wrenn 1975, p. 13.

- ↑ Historic Structure Report Volume 1 1981, p. 30.

- ↑ "AIR SHOW DEDICATES FLOYD Bennett Field ; Pilots Thrill Crowd of 25,000 in Exhibitions at Opening of City's First Airport. WALKER EXTOLS DEAD HERO Parade of Air Armada Passes in Review Before Stands as Climax of the Day. AIR SHOW DEDICATES NEW Bennett Field" (PDF). The New York Times. May 24, 1931. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- 1 2 3 Cody 2009, p. 53.

- ↑ "NEW RIIS PARK SPAN IS OPENED BY MAYOR; He Pays High Tribute to Moses at Dedication of Bridge Over Rockaway Inlet" (PDF). The New York Times. July 4, 1937. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 9, 2017.

- ↑ "50,000 Watch As Navy Accepts Bennett Field". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. June 2, 1941. pp. 1, 11 – via Brooklyn Public Library; newspapers.com.

- ↑ Historic Structure Report Volume 1 1981, p. 60.

- ↑ Historic Structure Report Volume 1 1981, p. 63.

- ↑ "U.S. TAKES AIRPORT TRACT; Gets 51 Acres to Expand Floyd Bennett Naval Air Base" (PDF). The New York Times. January 6, 1942. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ↑ Cody 2009, p. 119.

- ↑ "The Delights of Collecting Trash at Dead Horse Bay". Slate. January 6, 2014. ISSN 1091-2339. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ↑ Simon, Evan; Smith, Olivia (October 26, 2015). "Dead Horse Bay: New York's Hidden Treasure Trove of Trash". ABC News. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ↑ "Barren Island, by Carol Zoref, 2017 National Book Award Longlist, Fiction". National Book Award. Retrieved December 4, 2017.

- ↑ "AWP: Award Series Winners". Association of Writers & Writing Programs. Retrieved December 4, 2017.

Bibliography

- Black, Frederick R. (1981). "JAMAICA BAY: A HISTORY" (PDF). United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service.

- Blakemore, Porter R.; Linck, Dana C. (May 1981). "Historic Structure Report: Floyd Bennett Field ; Gateway National Recreation Area, New Jersey-New York" (PDF). 1. United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 11, 2014.

- Cody, Sarah K.; Auwaerter, John; Curry, George W. (2009). "Cultural Landscape Report for Floyd Bennett Field" (PDF). nps.gov. State University of New York, College of Environmental Science and Forestry.

- Dubois, Anson (1884). A History of the Town of Flatlands, Kings County, N.Y.

- Seitz, Sharon; Miller, Stuart (2011). The Other Islands of New York City: A History and Guide (Third Edition). Countryman Press. pp. 257–264. ISBN 978-1-58157-886-7.

- Wrenn, Tony P. (October 31, 1975). "GENERAL HISTORY OF THE JAMAICA BAY, BREEZY POINT, AND STATEN ISLAND UNITS, GATEWAY NATIONAL RECREATION AREA, NEW YORK NY" (PDF).