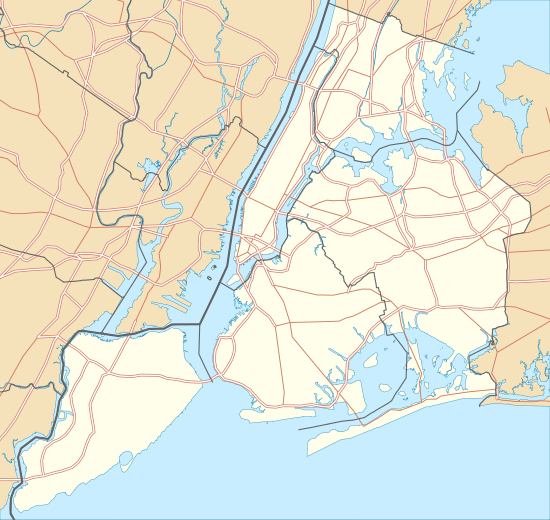

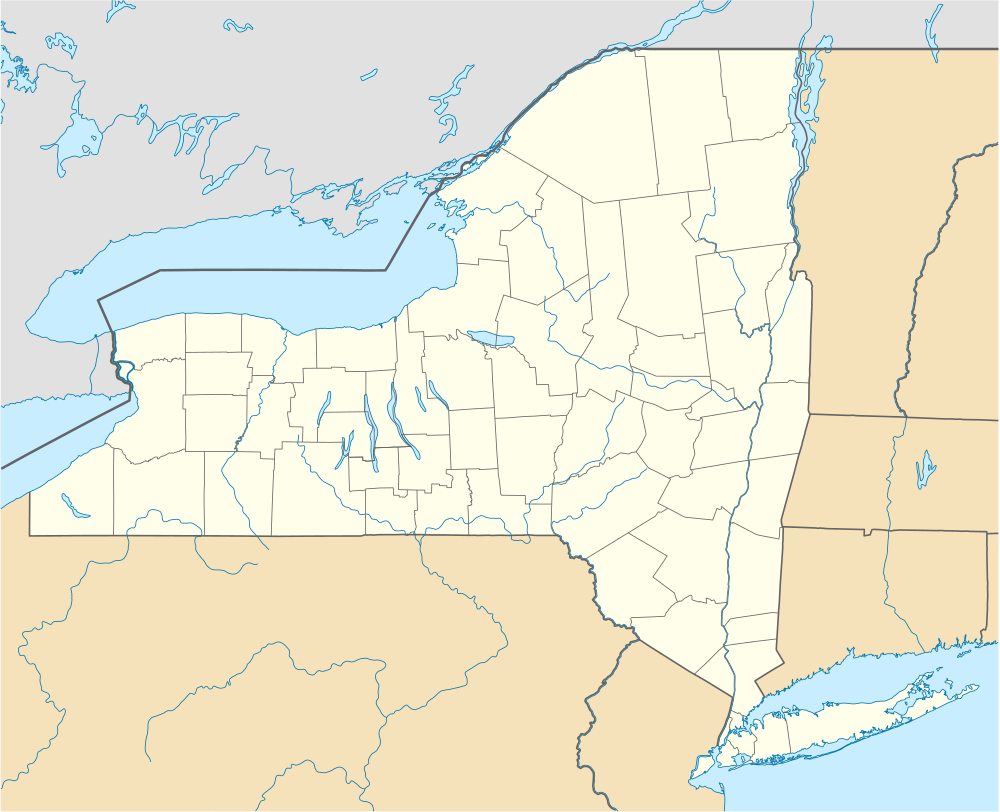

Hart Island (Bronx)

Hart Island  Hart Island  Hart Island | |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Long Island Sound |

| Coordinates | 40°51′9″N 73°46′12″W / 40.85250°N 73.77000°WCoordinates: 40°51′9″N 73°46′12″W / 40.85250°N 73.77000°W |

| Archipelago | Pelham Islands |

| Area | 131.22 acres (53.10 ha) |

| Length | 1.0 mi (1.6 km) |

| Width | 0.25 mi (0.4 km) |

| Administration | |

|

| |

| State |

|

| City | New York City |

| Borough | Bronx |

Hart Island, sometimes referred to as Hart's Island, is an island in New York City at the western end of Long Island Sound. It is approximately 1 mile (1.6 km) long by 1⁄4 mile (0.40 km) wide and is located to the northeast of City Island in the Pelham Islands group. The island is the easternmost part of the borough of the Bronx.

The first public use of Hart Island was to train United States Colored Troops in 1864. Since then, the island has been used as a Union Civil War prison camp, a psychiatric institution, a tuberculosis sanatorium, potter's field, and a boys' reformatory.[1] During the Cold War, Nike defense missiles were also stationed on Hart Island. The island now serves as the city's potter's field and is run by the New York City Department of Correction.

Etymology

There are several versions of the origin of the island's name. In one, British cartographers named it "Heart Island" in 1775, due to its organ-like shape, but the second letter was dropped shortly thereafter.[2]

Others sources indicate that "hart" refers to an English word for "stag." One version of this theory is that the island was given the name when it was used as a game preserve.[3] Another version holds that it was named in reference to deer that migrated from the mainland during periods when ice covered that part of Long Island Sound.[4]:19 A passage in William Styron's novel Lie Down in Darkness[5] describes the island as occupied by a lone deer shot by a hunter in a row boat. Styron provides a vivid description of the public burials following World War II including the handling of remains from re-excavated graves.

History

.jpg)

_sheet_1.jpg)

The island was part of the 0.2-square-mile (0.52 km2) property purchased by Thomas Pell from the local Native Americans in 1654.[6] On May 27, 1868, New York City purchased the island from Edward Hunter of the Bronx for $75,000.[2][7] The first public use of Hart Island was to train United States Colored Troops beginning in 1864.[8]

Prison

Hart Island was a prisoner-of-war camp for four months in 1865 during the American Civil War. The island housed 3,413 captured Confederate Army soldiers: of these, 235 died in the camp and were buried in Cypress Hills National Cemetery. Following the Civil War indigent veterans were buried in a Soldier's Plot on Hart Island which was separate from Potter's Field and at the same location. Some of these soldiers were moved to West Farms Soldiers Cemetery in 1916 and others were removed to Cypress Hills Cemetery, Brooklyn in 1941.[9] People were later quarantined on the island during the 1870 yellow fever epidemic and at various times it has been home to a women's psychiatric hospital (The Pavilion, 1885), a tubercularium,[10] and a workhouse for delinquent boys.[11]

The Department of Correction used the island for a prison up until 1966 and briefly again in the late 1980s. Access is controlled by the Department of Correction.

Cemetery

Hart Island is the location of the 131-acre (0.53 km2) public cemetery (potter's field) for New York City, the largest tax-funded cemetery in the world.[12][13][14] Although the name "Potter's Field" was previously on Wards Island, the Hart Island cemetery opened with the name City Cemetery, but is often nevertheless referred to as the "Potter's Field."

Burials on Hart Island began with 20 Union Army soldiers during the American Civil War. City burials started shortly after Hart Island was sold to New York City in 1868.[7] In 1869, the city buried a 24-year-old woman named Louisa Van Slyke who died in the Charity Hospital and was the first person to be buried in the island's 45-acre (180,000 m2) public graveyard.[15][4] In 1913, adults and children under five were buried in separate mass graves. Unknowns are mostly adults. They are frequently disinterred when families are able to locate their relatives through DNA, photographs and fingerprints kept on file at the Office of the Medical Examiner. Adults are buried in trenches with three sections of 48-50 individuals to make disinterment easier. Children, mostly infants, are rarely disinterred and are buried in trenches of 1,000.[4] Hart Island's southern end continued to accommodate the living up until Phoenix House moved in 1976. In 1977, the island was vandalized and many burial records were destroyed by a fire. Remaining records were transferred to the Municipal Archives in Manhattan.

More than one million dead are buried on the island, but since the 2000s, the burial rate is now fewer than 1,500 a year. One third of annual burials are infants and stillborn babies, which has been reduced from a proportion of one-half since children's health insurance began to cover all pregnant women in New York State.[4][16][17][18][19] In 2005 there were 1,419 burials in the potter's field on Hart Island, including 826 adults, 546 infants and stillborn babies, and 47 burials of dismembered body parts.[15] The dead are buried in trenches. Babies are placed in coffins of various sizes, and are stacked five coffins high and usually twenty coffins across. Adults are placed in larger pine boxes placed according to size and are stacked three coffins high and two coffins across.[4]

Burial records on microfilm at the Municipal Archives in Manhattan indicate that until 1913, burials of unknowns were in single plots, and identified adults and children were buried in mass graves.[20][21] In 1913, the trenches became separate in order to facilitate the more common disinterment of adults. The potter's field is also used to dispose of amputated body parts, which are placed in boxes labeled "limbs". Ceremonies have not been conducted at the burial site since the 1950s.[4]:83[22] In the past, burial trenches were re-used after 25–50 years, allowing for sufficient decomposition of the remains. Currently, historic buildings are being torn down to make room for new burials.[23] Because of the number of weekly interments made at the potter's field and the expense to the taxpayers, these mass burials are straightforward and conducted by Rikers Island inmates. Inmates stack the pine coffins in two rows, three high and 25 across, and each plot is marked with a single concrete marker. A tall white peace monument erected by New York City prison inmates following World War II is at the top of what was known as "Cemetery Hill" prior to the installation of the now abandoned Nike missile base at the northern end of Hart Island.

Those interred on Hart Island are not necessarily homeless or indigent; many are people who could either not afford the expenses of private funerals or who were unclaimed by relatives within a month of death. Notable burials include the Jewish playwright, film screenwriter, and director Leo Birinski was buried here in 1951, when he died alone and in poverty.[24] The American novelist Dawn Powell was buried on Hart Island in 1970, five years after her death, when the executor of her estate refused to reclaim her remains after medical studies. Academy Award winner Bobby Driscoll was also buried here when he died in 1968 because no one was able to identify his remains when he was found dead in an East Village tenement.[25]

Approximately fifty percent of the burials are children under five who are identified and died in New York City's hospitals. The mothers of these children are generally unaware of what it means to sign papers authorizing a "City Burial." These women as well as siblings often go looking many years later. Many others have families who live abroad or out of state and whose relatives search for years. Their search is made more difficult because burial records are currently kept within the prison system.[26] An investigation into the handling of the infant burials was opened in response to a criminal complaint made to the New York State Attorney General's Office on April 1, 2009.[26]

Until 1989, City Cemetery occupied 45 acres (18 ha) on the northern half of Hart Island, while the southern half of the island was habitable. In 1985, sixteen bodies infected with AIDS were buried at the southern tip of Hart Island, because it was believed that the dead AIDS victims would contaminate the other corpses with the disease. They were the only people to be buried in a separate grave; when it was later discovered that corpses could not transmit diseases to other corpses, the city started burying AIDS victims in the mass graves.[27] The first pediatric AIDS victim to die in New York City is buried in the only single grave on Hart Island with a concrete marker that reads SC (special child) B1 (Baby 1) 1985.[4]:83[27] Since then, thousands of AIDS victims have been buried on Hart Island, but the precise number of AIDS victims buried on the island is unknown.[27]

A Freedom of Information Act request for 50,000 burial records was granted to The Hart Island Project in 2008.[28][29] The 1,403 pages provided by the Department of Correction contain lists of all burials from 1985–2007. A second FOI request for records from September 1, 1977 to December 31, 1984 was submitted to the Department of Correction on June 2, 2008. New York City has located 502 pages from that period and they will soon be available to the public.[30] A lawsuit concerning "place of death" information redacted from the Hart Island burial records was filed against New York City on July 11, 2008 by the Law Office of David B. Rankin. It was settled out of court in January 2009. On May 10, 2010, New York Poets read the names of people buried and located through the Hart Island Project.[31]

Boys' workhouse

In the late 19th century Hart Island became the location of a boys' workhouse which was an extension of the prison and almshouse on Blackwell's Island, now Roosevelt Island. There is a section of old wooden houses and masonry institutional structures dating back to the late 19th and early 20th centuries that have fallen into disrepair. These are now being torn down to provide new ground for burials. Military barracks from the Civil War period were used prior to the construction of workhouse and hospital facilities. None of the original Civil War Period buildings are still standing. In the early 20th century, Hart Island housed about two thousand delinquent boys as well as old male prisoners from Blackwell's penitentiary. This prison population moved to Rikers Island when the prison on Roosevelt Island (then called Welfare Island)) was torn down in 1936. Remaining on Hart Island is a building constructed in 1885 as a women's insane asylum, the Pavilion, as well as Phoenix House, a drug rehabilitation facility that closed in 1976.

Missiles

The island has defunct Nike Ajax missile silos, battery NY-15 that were part of the United States Army base Fort Slocum from 1956–1961 and operated by the army's 66th Antiaircraft Artillery Missile Battalion.[15] Some silos are located on Davids' Island. The Integrated Fire Control system that tracked the targets and directed missiles was located in Fort Slocum. The last components of the missile system were closed in 1974.[32]

Access

Hart Island and the pier on Fordham Street on City Island are restricted areas under the jurisdiction of the New York City Department of Correction. The process of visiting the island has been improved due to efforts by The Hart Island Project and the New York Civil Liberties Union.[33] Starting July 2015, up to five family members accompanied by guests may visit grave sites on one weekend per month.[34] The first visit took place on July 19, 2015.[35] Since then, there have been two ferry trips to the island every month: one for family members and their guests, and one for members of the general public.[34] The ferry leaves from the restricted dock on City Island. There is legislation pending that would adjust the ferry trips to permit for more frequent and regular travel to Hart Island.[36]

Family members who wish to visit the island must request a visit ahead of time with the Department of Correction. New York City offers no provisions for individuals wanting to visit Hart Island without contacting the prison system.[37] The City of New York permits family visits, allows family members to leave mementos at grave sites, and maintains an online and telephone system for family members to schedule grave site visits.[38] Those who are able to get an appointment must arrive at a designated time, relinquish cameras and cell phones, sign a legal release, and produce government issued identification. Other members of the public are permitted to visit by prior appointment only. Interested parties were instructed to contact the Office of Constituent Services to schedule a visit to a gazebo located near the docking point of the ferry on Hart Island.[39] In 2017, the City increased the maximum allowable number of visitors per month from 50 to 70.[40]

The city's Department of Correction offered one guided tour of the island in 2000 at local residents' requests, and a few other visits to members of the City Island Civics Association and Community Board 10 in 2014. Visitors were allowed to see the outside of the ruined buildings, some of which dated back to the 1880s. An ecumenical group named the Interfaith Friends of Potter's Field has intermittently conducted memorial services on the island.[41]

Public engagement

On October 28, 2011, the New York City Council Committee on Fire and Criminal Justice held a hearing titled "Oversight: Examining the Operation of Potter's Field by the N.Y.C., Department of Correction on Hart Island."[42][43]

A bill to transfer jurisdiction to the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation was introduced on April 30, 2012.[44][45] The Hart Island Project testified in favor of this bill on September 27, 2012.[46] The bill was introduced again in March 2014 and a public hearing took place at City Hall on January 20, 2016.[47] Proponents of this action claim that it would make it significantly easier for loved ones to visit their dead, and that as a park Hart Island would be the ninth such public cemetery to become a public park. It would join other famous parks that were once cemeteries such as Madison Square Park, Washington Square Park, and Bryant Park.[48] Bill 0134 had a public hearing on January 20, 2016.[47][49][50][51][52]

Two bills passed in 2013 require the Department of Correction to make two sets of documents available online: a database of burials, and a visitation policy.[53] In April 2013, the Department of Correction published an online database of burials on the island.[54][55] The database contains data about all persons buried on the island since 1977, and contains 66,000 entries.[1]

A New York City Council public hearing on bills introduced to remedy public access to Hart Island took place on September 27, 2012.[56]

The Hart Island Project

Since 1994, The Hart Island Project[57] has independently assisted families in obtaining copies of public burial records. The group also helps people track down loved ones and negotiate visits.[58][59][60] The Hart Island Project was founded by New York artist Melinda Hunt in an effort to aid the loved ones of the dead buried on Hart Island. Historian Thomas Laqueur writes:

Woody Guthrie's song about the unnamed Mexican migrant dead has had a long resonant history. Hunt, in an emotionally related gesture, has researched, for years, in order to publish the names of as many as 850,000 paupers who lie in 101 acres of Hart Island where the city buries its anonymous dead.[61]

In 2011 the Hart Island Project completed an online database of burial records dating back to 1980. The Hart Island Project database has made it easier for the relatives and loved ones of the almost one million people buried on Hart Island to get information about the people that they have lost.[62] Information such as burial location, and other records have been collected on The Hart Island Project's database. The Hart Island Project has led to reforms of access to Hart Island such as opening the island monthly to everyone[63] and the legislation that requires the Department of Corrections to put burial records online.[54]

The Hart Island Project has also digitally mapped grave trenches using GPS. In 2014, an interactive map with GPS burial data and storytelling software "clocks of anonymity" was released as "The Traveling Cloud Museum".[64] The Traveling Cloud Museum collects publicly submitted stories of those who are listed in the burial record and who are otherwise anonymous. "Traveling Cloud Museum" was created to give people who knew the deceased an opportunity to add stories, photos, epitaphs, songs or videos linked to a personal profile.[65][66][67]

An art exhibition of people located through The Hart Island Project with help from Melinda Hunt was held at Westchester Community College in 2012.[68][69][70] In July 2015, The Hart Island Project collaborated with British landscape architects Ann Sharrock and Ian Fisher to present a landscape strategy to the New York City Council and the Parks Department.[71] Ann Sharrock introduced the concept that Hart Island is a natural burial facility and outlined a growing interest in green burials within urban settings.[47][72]

See also

References

- 1 2 Corey Kilgannon (November 15, 2013). "Visiting the Island of the Dead. A Rare Visit to New York's Potter's Field on Hart Island". New York Times. Retrieved November 17, 2013.

- 1 2 Santora, Marc (January 27, 2003). "An Island Of the Dead Fascinates The Living". The New York Times. Retrieved April 4, 2010.

During World War II, the Navy used the workhouses on the island as a disciplinary barracks. After the war, in 1955, the Army installed a Nike missile base to defend against an attack by Soviet long-range bombers. The 21-foot missiles were stored underground, and Miller writes that the complex needed a generator powerful enough to provide electricity for a town of 10,000.

- ↑ "The Islands of Pelham Bay". New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. Retrieved November 15, 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Hunt, Melinda; Joel Sternfeld. Hart Island. ISBN 3-931141-90-X.

- ↑ "William Styron – About William Styron | American Masters". PBS. October 8, 2002. Retrieved April 11, 2014.

- ↑ Lustenberger, Anita A. (2000). "A Short Genealogy of Hart Island". New York Genealogical and Biographical Society. Retrieved November 5, 2006. (subscription required)

- 1 2 "Purchase of Hart's Island". The New York Times. February 27, 1869. Retrieved April 4, 2010.

The Department of Charities and Correction have bought from Mr. Edward Hunter, Hart's Island, in Long Island Sound, and about sixteen miles from the City, for the purpose of establishing there an industrial school for destitute boys, who may be too large for the school on Randall's Island.

- ↑ "Civil War Colored Troops on DOC islands". Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ↑ "cwpows7". Correctionhistory.org. Retrieved April 11, 2014.

- ↑ "Grand Jury Says Hart's Island Tuberculosis Ward is Unsuitable". The New York Times. November 10, 1917. p. 13. Retrieved April 10, 2010.

- ↑ "Likes Life in Workhouse: Inmates Writes of 'Good Eats, No Work, and Bum Arguments'" (PDF). The New York Times. 1915-10-03. Retrieved 2018-07-04.

- ↑ "Finding relatives in Potter's Field | 7online.com". Abclocal.go.com. February 4, 2009. Retrieved April 11, 2014.

- ↑ "CCM News". Clients.ccm-news.com. Retrieved April 11, 2014.

- ↑ "One Million People Buried in Mass Graves on Forbidden New York Island". RealClear.com. April 9, 2014.

- 1 2 3 Emily Brady. "A Chance to Be Mourned".

New York’s mass burial ground is a grassy place surrounded by the waters of Long Island Sound. By the time the city purchased the island, in 1868, there had already been nine potter’s fields around Manhattan.

- ↑ Thomas Antenen, NYC Department of Correction Interview 2002

- ↑ "Sadness in Our Hearts". The New York Times. May 30, 2007. Retrieved August 21, 2007.

- ↑ Final Exits: The Illustrated Encyclopedia of How We Die by Michael Largo. HarperCollins Publishers, New York City: 2006, ISBN 0-06-081741-0, pages 407–408.

- ↑ "Third world America: Bodies driven to a pauper's burial in a U-Haul as tough economic times lead to more mass graves". Mail Online. January 19, 2012.

- ↑ "Where the Unknown Dead Rest". The New York Times. February 1, 1874. p. 8. Retrieved April 10, 2010.

- ↑ "Unearthing the Secrets of New York's Mass Graves". The New York Times. May 15, 2016. Retrieved May 17, 2016.

- ↑ In Essentials, Unity; In Non-Essentials, Liberty; and in All Things Charity: A Historical Account of the Mission of the Diocese of New York of the Protestant Episcopal Church to the Institutions and the Potter's Field on Hart Island, by Wayne Kempton, archivist of the Episcopal Diocese of New York

- ↑ "Island of the Dead (Island Week)". Google Sightseeing. August 31, 2006. Retrieved April 11, 2014.

- ↑ Municipal Archives of The New York City.

- ↑ Clay Risen. "Hart Island". The Morning News. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- 1 2 "Hart Island Babies". myFoxNY.com. Fox Television Stations. Archived from the original on June 5, 2011.

- 1 2 3 "Dead of AIDS and Forgotten in Potter's Field". The New York Times. 2018-07-03. Retrieved 2018-07-04.

- ↑ Buckley, Cara (March 24, 2008). "Finding Names for Hart Island's Forgotten". The New York Times. Retrieved April 10, 2010.

- ↑ Chan, Sewell (November 26, 2007). "Searching for Names on an Island of Graves". The New York Times. Retrieved April 10, 2010.

- ↑ "About – Home Page". Hartisland.net. Retrieved April 11, 2014.

- ↑ Archived May 22, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Vanderbilt, Tom (March 5, 2000). "When Nike Meant More Than 'Just Do It'". The New York Times. Retrieved August 25, 2008.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 13, 2016. Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- 1 2 Kilgannon, Corey (July 9, 2015). "New York City to Allow Relatives to Visit Grave Sites at Potter's Field". The New York Times. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ↑ "Mourners Make First Visit to New York's Potter's Field". The New York Times. July 20, 2015. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ↑ "File #: Int 0133-2014". The New York City Council. Retrieved 2018-07-04. .

- ↑ "HartIslandProject". Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on December 1, 2015. Retrieved July 29, 2015.

- ↑ {{cite web | title=FAQ | website=HartIslandProject | url=https://www.hartisland.net/faq | access-date=2018-07-04}

- ↑ "City Agrees To Increase Mourners' Access To Mass Graves On Hart Island". Archived from the original on January 26, 2017. Retrieved January 24, 2017.

- ↑ A reflection by one of the organizers of the memorial services. Archived November 28, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Hennelly, Bob (October 28, 2011). "Council Looking Into City Cemetery". WNYC. Archived from the original on April 27, 2012. Retrieved August 25, 2013.

- ↑ Mathias, Christopher (October 30, 2011). "Hart Island Cemetery: City Council Reviews Operations Of New York's Potter's Field (VIDEO)". Huffington Post.

- ↑ Darius Tajanko. "The New York City Council - File #: Int 0133-2014". Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ↑ Rocchio, Patrick (2014-11-14). "City Island Civic Association, Chamber visit Hart Island and take tour". Bronx Times. Retrieved 2018-07-04.

- ↑ "The New York City Council - Video". Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Officials Object to Plan to Turn Hart Island Burial Site Over to Parks Dept". The New York Times. January 21, 2016. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ↑ Waldman, Benjamin (2013-07-12). "Surprise! What NYC's Former Cemeteries Are Now". Untapped Cities. Retrieved 2018-07-04.

- ↑ The Editors (January 26, 2016). "Open the Hart of New York". Observer. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ↑ "NYC Discusses Turning Hart Island Into a Park - Al Jazeera America". Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ↑ Maria Alvarez (January 20, 2016). "NYC Council hears plan to turn island of forgotten into park - am New York". am New York. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ↑ "Who Should Control Hart Island, NYC's "Prison For The Dead"?". Gothamist. Archived from the original on May 3, 2016. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ↑ "Bill 803". Legistar.council.nyc.gov. Retrieved April 11, 2014.

- 1 2 "City Island - City Launches Online Database for Massive Hart Island Potter's Field - Neighborhood News - DNAinfo New York". DNAinfo New York. Archived from the original on January 9, 2016. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ↑ "Hart Island - NYC Department of Correction". Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ↑ Velsey, Kim (September 28, 2012). "An Open Hart Island: Off the Coast of the Bronx Lie 850,000 Lost Souls—the City Council Hopes to Pay Its Respects". The New York Observer. Retrieved August 25, 2013.

- ↑ Hart Island Project web site Archived May 16, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Remizowski, Leigh (March 11, 2012). "New Yorker helps people track down loved ones who died unknown". CNN. Retrieved August 25, 2013.

- ↑ Silverman, Alex (November 14, 2011). "Melinda Hunt Follows NYC's Lonely Dead To Hart Island". WCBS 880. Retrieved August 25, 2013.

- ↑ "Relatives Of Deceased Push For More Access To NYC Potter's Field". NPR.org. February 4, 2016. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ↑ "Laqueur, T.W.: The Work of the Dead: A Cultural History of Mortal Remains. (eBook and Hardcover)". Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ↑ "HartIslandProject". Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ↑ http://s-media.nyc.gov/agencies/cityrecord/CITY%20COUNCIL%20SUPPLEMENTS/NEW%20SUPPLEMENTS%20RECIEVED%20ON%20MARCH%205,%202014%20by%20email/FINAL%2011x17%20121013-revised.pdf

- ↑ "Is your family member buried on Hart Island, off the coast of New York? Sorry, you can't visit". Public Radio International. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ↑ "The Hart Island Project." HartIslandProject. January 5, 2015.

- ↑ "A Digital Museum for New York's Unclaimed Dead". Hyperallergic. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ↑ "Traveling Cloud Museum — Atlas of the Future". Atlas of the Future. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ↑ Hodara, Susan (December 30, 2011). "Giving Voice to the Legions Buried in a Potter's Field". The New York Times. Retrieved August 25, 2013.

- ↑ Blotcher, Jay (November 30, 2011). "The Art of the Forgotten". The Art of the Forgotten. Retrieved August 25, 2013.

- ↑ Rojas, Marcela (November 12, 2011). "Peekskill artist helps families find those buried at Hart Island". The Journal News. Retrieved August 25, 2013.

- ↑ "HartIslandProject". Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ↑ "Could NYC's Island of the Dead Become a Green Burial Park?". Hyperallergic. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

Further reading

- Hart Island; Melinda Hunt and Joel Sternfeld; ISBN 3-931141-90-X

- Digging Hart Island, New York’s 850,000-Corpse Potter’s Field by Doc Searls, September 23, 2013

- The Nature of Hart Island Essay by Melinda Hunt from Book: Hart Island, Scalo 1998.

- Hart Island website by the New York Correction History Society

- A Historical Resumé of Potter's Field, 1869–1967 – a 16-page flyer published by the NYC Department of Correction in 1967. (Excerpts in HTML here).

- In Essentials, Unity; In Non-Essentials, Liberty; and in All Things Charity: A Historical Account of the Mission of the Diocese of New York of the Protestant Episcopal Church to the Institutions and the Potter's Field on Hart Island, by Wayne Kempton, archivist of the Episcopal Diocese of New York

- The Fort Slocum Nike Installation

- Brief History of Hart Island Nike Missile Site by the New York Correction History Society

- Hart Island: An American Cemetery, documentary film by Melinda Hunt

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hart Island, New York. |

- The Hart Island Project at hartisland.org

- Hart Island at Google Sightseeing

- Hart Island at Find A Grave