The Birth of a Nation

| The Birth of a Nation | |

|---|---|

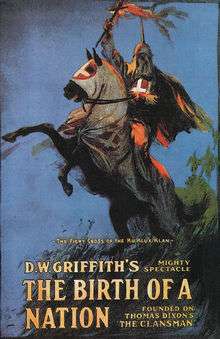

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | D. W. Griffith |

| Produced by |

D. W. Griffith Harry Aitken[1] |

| Screenplay by |

D. W. Griffith Frank E. Woods |

| Based on |

The Clansman and The Leopard's Spots by T. F. Dixon Jr. |

| Starring |

Lillian Gish Mae Marsh Henry B. Walthall Miriam Cooper Ralph Lewis George Siegmann Walter Long |

| Music by | Joseph Carl Breil |

| Cinematography | G. W. Bitzer |

| Edited by | D. W. Griffith |

Production company |

David W. Griffith Corp. |

| Distributed by | Epoch Producing Co. |

Release date |

|

Running time |

12 reels 133–193 minutes[note 1][2] |

| Country | United States |

| Language |

Silent film English intertitles |

| Budget | >$100,000[3] |

| Box office | unknown; estimated $50–100 million[4] |

The Birth of a Nation (originally called The Clansman) is a 1915 American silent epic drama film directed and co-produced by D. W. Griffith and starring Lillian Gish. The screenplay is adapted from the novel and play The Clansman, both by Thomas Dixon Jr., as well as Dixon's novel The Leopard's Spots. Griffith co-wrote the screenplay with Frank E. Woods, and co-produced the film with Harry Aitken. It was released on February 8, 1915.

The film is three hours long[5] and was originally presented in two parts separated by an intermission; it was the first 12-reel film in the United States. The film chronicles the relationship of two families in the American Civil War and Reconstruction Era over the course of several years: the pro-Union Northern Stonemans and the pro-Confederacy Southern Camerons. The assassination of Abraham Lincoln by John Wilkes Booth is dramatized.

The film was a commercial success, though it was highly controversial for its portrayal of black men (many played by white actors in blackface) as unintelligent and sexually aggressive towards white women, and the portrayal of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) as a heroic force.[6][7] There were widespread black protests against The Birth of a Nation, such as in Boston, while thousands of white Bostonians flocked to see the film.[8] The NAACP spearheaded an unsuccessful campaign to ban the film.[8] Griffith's indignation at efforts to censor or ban the film motivated him to produce Intolerance the following year.[9]

The film's release is also credited as being one of the events that inspired the reformation of the Ku Klux Klan in 1915. The Birth of a Nation was the first American motion picture to be screened inside the White House, viewed there by President Woodrow Wilson.[10] Griffith's innovative techniques and storytelling power have made The Birth of a Nation one of the landmarks of film history.[11][12]

In 1992, the Library of Congress deemed the film "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" and selected it for preservation in the National Film Registry.

Plot

Part 1: Civil War of United States

_-_5.jpg)

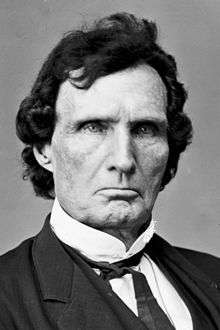

The film follows two juxtaposed families. One is the Northern Stonemans: abolitionist U.S. Representative Austin Stoneman (based on the Reconstruction-era Representative Thaddeus Stevens),[13][14] his daughter, and two sons. The other is the Southern Camerons: Dr. Cameron, his wife, their three sons and two daughters. Phil, the elder Stoneman son, falls in love with Margaret Cameron, during the brothers' visit to the Cameron estate in South Carolina, representing the Old South. Meanwhile, young Ben Cameron idolizes a picture of Elsie Stoneman. During the Civil War, the young men from both families enlist in their respective armies for the war. The younger Stoneman and two of the Cameron brothers are killed in the war. Meanwhile, the Cameron women are rescued by Confederate soldiers who rout a black militia, after an attack on the Cameron home. Ben Cameron leads a heroic charge at the Siege of Petersburg, earning the nickname of "the Little Colonel", but he is also wounded and captured. He is then taken to a Union hospital in Washington, D.C.

During his stay at the hospital, he is told that he will be hanged. Also at the hospital, he meets Elsie Stoneman, whose picture he has been carrying; she is working there as a nurse. Elsie takes Cameron's mother, who had traveled to Washington to tend her son, to see Abraham Lincoln, and Mrs. Cameron persuades the President to pardon Ben. When Lincoln is assassinated at Ford's Theatre, his conciliatory postwar policy expires with him. In the wake of the president's death, Austin Stoneman and other Radical Republicans are determined to punish the South, employing harsh measures that Griffith depicts as having been typical of the Reconstruction Era.[15]

Part 2: Reconstruction

Stoneman and his protégé Silas Lynch, a mulatto exhibiting psychopathic tendencies,[16] head to South Carolina to observe the implementation of Reconstruction policies firsthand. During the election, in which Lynch is elected lieutenant governor, blacks are observed stuffing the ballot boxes, while many whites are denied the vote. The newly elected, mostly black members of the South Carolina legislature are shown at their desks displaying inappropriate behavior, such as one member taking off his shoe and putting his feet up on his desk, and others drinking liquor and feasting on stereotypically African-American fare such as fried chicken.

Meanwhile, inspired by observing white children pretending to be ghosts to scare black children, Ben fights back by forming the Ku Klux Klan. As a result, Elsie, out of loyalty to her father, breaks off her relationship with Ben. Later, Flora Cameron goes off alone into the woods to fetch water and is followed by Gus, a freedman and soldier who is now a captain. He confronts Flora and tells her that he desires to get married. Frightened, she flees into the forest, pursued by Gus. Trapped on a precipice, Flora warns Gus she will jump if he comes any closer. When he does, she leaps to her death. Having run through the forest looking for her, Ben has seen her jump; he holds her as she dies, then carries her body back to the Cameron home. In response, the Klan hunts down Gus, tries him, finds him guilty, and lynches him.

Lynch then orders a crackdown on the Klan after discovering Gus's murder. He also secures the passing of legislation allowing mixed-race marriages. Dr. Cameron is arrested for possessing Ben's Klan regalia, now considered a crime punishable by death. He is rescued by Phil Stoneman and a few of his black servants. Together with Margaret Cameron, they flee. When their wagon breaks down, they make their way through the woods to a small hut that is home to two sympathetic former Union soldiers who agree to hide them. An intertitle states, "The former enemies of North and South are united again in defense of their Aryan birthright."

Congressman Stoneman leaves to avoid being connected with Lt. Gov. Lynch's crackdown. Elsie, learning of Dr. Cameron's arrest, goes to Lynch to plead for his release. Lynch, who had been lusting after Elsie, tries to force her to marry him, which causes her to faint. Stoneman returns, causing Elsie to be placed in another room. At first, Stoneman is happy when Lynch tells him he wants to marry a white woman, but is then angered when Lynch tells him that it is Stoneman's daughter. Undercover Klansmen spies go to get help when they discover Elsie's plight after she breaks a window and cries out for help. Elsie falls unconscious again, and revives while gagged and being bound. The Klan, gathered together and with Ben leading them, rides in to gain control of the town. When news about Elsie reaches Ben, he and others go to her rescue. Elsie frees her mouth and screams for help. Lynch is captured. Victorious, the Klansmen celebrate in the streets. Meanwhile, Lynch's militia surrounds and attacks the hut where the Camerons are hiding. The Klansmen, with Ben at their head, race in to save them just in time. The next election day, blacks find a line of mounted and armed Klansmen just outside their homes, and are intimidated into not voting.

The film concludes with a double wedding as Margaret Cameron marries Phil Stoneman and Elsie Stoneman marries Ben Cameron. The masses are shown oppressed by a giant warlike figure who gradually fades away. The scene shifts to another group finding peace under the image of Jesus Christ. The penultimate title is: "Dare we dream of a golden day when the bestial War shall rule no more. But instead — the gentle Prince in the Hall of Brotherly Love in the City of Peace."

Cast

- Lillian Gish as Elsie Stoneman

- Mae Marsh as Flora Cameron, the pet sister

- Henry B. Walthall as Colonel Benjamin Cameron ("The Little Colonel")

- Miriam Cooper as Margaret Cameron, elder sister

- Mary Alden as Lydia Brown, Stoneman's housekeeper

- Ralph Lewis as Austin Stoneman, Leader of the House

- George Siegmann as Silas Lynch

- Walter Long as Gus, the renegade

- Wallace Reid as Jeff, the blacksmith

- Joseph Henabery as Abraham Lincoln

- Elmer Clifton as Phil Stoneman, elder son

- Robert Harron as Tod Stoneman

- Josephine Crowell as Mrs. Cameron

- Spottiswoode Aitken as Dr. Cameron

- George Beranger as Wade Cameron, second son

- Maxfield Stanley as Duke Cameron, youngest son

- Jennie Lee as Mammy, the faithful servant

- Donald Crisp as General Ulysses S. Grant

- Howard Gaye as General Robert E. Lee

Uncredited:

- Edmund Burns as Klansman

- David Butler as Union soldier / Confederate soldier

- William Freeman as Jake, a mooning sentry at Federal hospital

- Sam De Grasse as Senator Charles Sumner

- Olga Grey as Laura Keene

- Russell Hicks

- Elmo Lincoln as ginmill owner / slave auctioneer

- Eugene Pallette as Union soldier

- Harry Braham as Jake / Nelse

- Charles Stevens as volunteer

- Madame Sul-Te-Wan as woman with gypsy shawl

- Raoul Walsh as John Wilkes Booth

- Lenore Cooper as Elsie's maid

- Violet Wilkey as young Flora

- Tom Wilson as Stoneman's servant

- Donna Montran as belles of 1861

- Alberta Lee as Mrs. Mary Todd Lincoln

- Allan Sears as Klansmen

- Vester Pegg

- Alma Rubens

- Mary Wynn

- Jules White

- Monte Blue

- Gibson Gowland

- Fred Burns

- Alberta Franklin

- Charles King

- William E. Cassidy

Production

In 1912, Thomas Dixon Jr. decided that he wanted to turn his popular 1905 novel and play The Clansman into a film, and began visiting various studios to see if they were interested.[17] In late 1913, Dixon met the film producer Harry Aitken, who was interested in making a film out of The Clansman, and through Aitken, Dixon met Griffith.[17] Griffith was the son of a Confederate officer and, like Dixon, viewed Reconstruction negatively. Griffith believed that a passage from The Clansman where Klansmen ride "to the rescue of persecuted white Southerners" could be adapted into a great cinematic sequence.[18] Griffith began production in July 1914 and was finished by October 1914.[19] The Birth of a Nation began filming in 1914 and pioneered such camera techniques as close-ups, fade-outs, and a carefully staged battle sequence with hundreds of extras made to look like thousands.[20] It also contained many new artistic techniques, such as color tinting for dramatic purposes, building up the plot to an exciting climax, dramatizing history alongside fiction, and featuring its own musical score written for an orchestra.[21]

The film was based on Dixon's novels The Clansman and The Leopard's Spots. It was originally to have been shot in Kinemacolor, but D. W. Griffith took over the Hollywood studio of Kinemacolor and its plans to film Dixon's novel. Griffith, whose father served as a colonel in the Confederate States Army, agreed to pay Thomas Dixon $10,000 (equivalent to $244,319 today) for the rights to his play The Clansman. Since he ran out of money and could afford only $2,500 of the original option, Griffith offered Dixon 25 percent interest in the picture. Dixon reluctantly agreed, and the unprecedented success of the film made him rich. Dixon's proceeds were the largest sum any author had received for a motion picture story and amounted to several million dollars.[21] The American historian John Hope Franklin suggested that many aspects of the script for The Birth of a Nation appeared to reflect Dixon's concerns more than Griffith's, as Dixon had an obsession in his novels of describing in loving detail the lynchings of black men, which did not reflect Griffith's interests.[22]

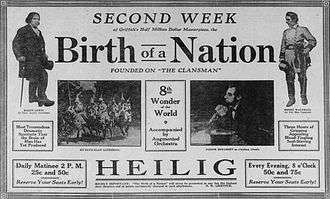

Griffith's budget started at US$40,000[21] (equivalent to $970,000 today) but rose to over $100,000[3] (the equivalent of $2,420,000 in constant dollars).[23] West Point engineers provided technical advice on the American Civil War battle scenes, providing Griffith with the artillery used in the film.[24] Some scenes from the movie were filmed on the porches and lawns of Homewood Plantation in Natchez, Mississippi.[25] The film premiered on February 8, 1915, at Clune's Auditorium in downtown Los Angeles. At its premiere the film was entitled The Clansman; the title was later changed to The Birth of a Nation to reflect Griffith's belief that the United States emerged from the American Civil War and Reconstruction as a unified nation.[26]

Score

Although The Birth of a Nation is commonly regarded as a landmark for its dramatic and visual innovations, its use of music was arguably no less revolutionary.[27] Though film was still silent at the time, it was common practice to distribute musical cue sheets, or less commonly, full scores (usually for organ or piano accompaniment) along with each print of a film.[28]

For The Birth of a Nation, composer Joseph Carl Breil created a three-hour-long musical score that combined all three types of music in use at the time: adaptations of existing works by classical composers, new arrangements of well-known melodies, and original composed music.[27] Though it had been specifically composed for the film, Breil's score was not used for the Los Angeles première of the film at Clune's Auditorium; rather, a score compiled by Carli Elinor was performed in its stead, and this score was used exclusively in West Coast showings. Breil's score was not used until the film debuted in New York at the Liberty Theatre, and was the score utilized in all showings save those on the West Coast.[29][30]

Outside of original compositions, Breil adapted classical music for use in the film, including passages from Der Freischütz by Carl Maria von Weber, Leichte Kavallerie by Franz von Suppé, Symphony No. 6 by Ludwig van Beethoven, and "Ride of the Valkyries" by Richard Wagner, the latter used as a leitmotif during the ride of the KKK.[27] Breil also arranged several traditional and popular tunes that would have been recognizable to audiences at the time, including many Southern melodies; among these songs were "Maryland, My Maryland", "Dixie",[31] "Old Folks at Home", "The Star-Spangled Banner", "America the Beautiful", "The Battle Hymn of the Republic", "Auld Lang Syne", and "Where Did You Get That Hat?".[27][32] DJ Spooky has called Breil's score, with its mix of Dixieland songs, classical music and "vernacular heartland music" "an early, pivotal accomplishment in remix culture." He has also cited Breil's use of music by Richard Wagner as influential on subsequent Hollywood films, including Star Wars (1977) and Apocalypse Now (1979); the latter film also makes use of "Ride of the Valkyries".[33]

In his original compositions for the film, Breil wrote numerous leitmotifs to accompany the appearance of specific characters. The principal love theme that was created for the romance between Elsie Stoneman and Ben Cameron was published as "The Perfect Song" and is regarded as the first marketed "theme song" from a film; it was later used as the theme song for the popular radio and television sitcom Amos 'n' Andy.[29][30]

Release

Responses

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), founded in 1909, protested at premieres of the film in numerous cities. According to the historian David Copeland, "by the time of the movie's March 3 [1915] premiere in New York City, its subject matter had embroiled the film in charges of racism, protests, and calls for censorship, which began after the Los Angeles branch of the NAACP requested the city's film board ban the movie. Since film boards were composed almost entirely of whites, few review boards initially banned Griffith's picture".[34] The NAACP also conducted a public education campaign, publishing articles protesting the film's fabrications and inaccuracies, organizing petitions against it, and conducting education on the facts of the war and Reconstruction.[35] Because of the lack of success in NAACP's actions to ban the film, on April 17, 1915, NAACP secretary Mary Childs Nerney wrote to NAACP Executive Committee member George Packard: "I am utterly disgusted with the situation in regard to The Birth of a Nation ... kindly remember that we have put six weeks of constant effort of this thing and have gotten nowhere."[36]

Jane Addams, an American social worker and social reformer, and the founder of Hull House, voiced her reaction to the film in an interview published by the New York Post on March 13, 1915, just ten days after the film was released.[37] She stated that "One of the most unfortunate things about this film is that it appeals to race prejudice upon the basis of conditions of half a century ago, which have nothing to do with the facts we have to consider to-day. Even then it does not tell the whole truth. It is claimed that the play is historical: but history is easy to misuse."[37] In New York, Rabbi Stephen Samuel Wise told the press after seeing The Birth of a Nation that the film was "an indescribable foul and loathsome libel on a race of human beings".[38] In Boston, the civil rights activist William Monroe Trotter organized demonstrations against the film, which he predicted was going to worsen race relations, while Booker T. Washington wrote a newspaper column asking readers to boycott the film.[38] Trotter's demonstration resulted in a riot.[39] In Washington D.C, the Reverend Francis James Grimké published a pamphlet entitled "Fighting a Vicious Film" that challenged the historical accuracy of The Birth of a Nation on a scene-by-scene basis.[40] When the film was released, riots also broke out in Philadelphia and other major cities in the United States. The film's inflammatory nature was a catalyst for gangs of whites to attack blacks. On April 24, 1916, the Chicago American reported that a white man murdered a black teenager in Lafayette, Indiana, after seeing the film, although there has been some controversy as to whether the murderer had actually seen The Birth of a Nation.[41] The mayor of Cedar Rapids, Iowa was the first of twelve mayors to ban the film in 1915 out of concern that it would promote race prejudice, after meeting with a delegation of black citizens.[42] The NAACP set up a precedent-setting national boycott of the film, likely seen as the most successful effort. Additionally, they organized a mass demonstration when the film was screened in Boston, and it was banned in three states and several cities.[43]

Both Griffith and Dixon in letters to the press dismissed African-American protests against The Birth of a Nation, saying that the reason black men disliked the film was because they wanted to have sex with white women, and the film depicted miscegenation as an evil.[44] In a letter to The New York Globe, Griffith wrote that his film was "an influence against the intermarriage of blacks and whites".[44] Dixon likewise called the NAACP "the Negro Intermarriage Society" and said it was against The Birth of a Nation "for one reason only—because it opposes the marriage of blacks to whites".[44] Griffith—indignant at the film's negative critical reception—wrote letters to newspapers and published a pamphlet in which he accused his critics of censoring unpopular opinions.[45] Griffith's 1916 pamphlet The Rise and Fall of a Free Speech in America used racialized language and images, such as a cartoon that depicted "censorship" as a monstrous black man with a lascivious expression on his face eyeing "free speech" who appeared as a white woman dressed in a white dress.[46] "Free Speech" points at "Censorship" and says: "All history, all reason condemns you: GO!".[46] In his pamphlet, Griffith called censorship "this malignant pygmy" who had mutated into a fully grown "Caliban" (a character from William Shakespeare's play The Tempest who is often depicted as a black man).[44]

When Sherwin Lewis of The New York Globe wrote a piece that expressed criticism of the film's distorted portrayal of history, and said that it was not worthy of constitutional protection because its purpose was to make a few "dirty dollars", Griffith responded that "the public should not be afraid to accept the truth, even though it might not like it". He also added that the man who wrote the editorial was "damaging my reputation as a producer" and "a liar and a coward".[47] In November 1915, William Joseph Simmons revived the Klan in Atlanta, Georgia.[48] The historian John Hope Franklin observed that, had it not been for The Birth of a Nation, the Klan might not have been reborn.[49]

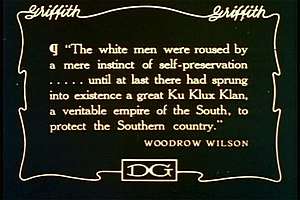

Special screenings

Thomas Dixon, Jr. was a former classmate of then-president Woodrow Wilson at Johns Hopkins University. Dixon arranged a screening of The Birth of a Nation at the White House for Wilson, members of his cabinet, and their families, in one of the first ever screenings at the White House. Wilson was falsely reported to have said of the film, "It is like writing history with lightning. And my only regret is that it is all so terribly true".[51] Wilson's aide, Joseph Tumulty, denied the claims and said that "the President was entirely unaware of the nature of the play before it was presented and at no time has expressed his approbation of it."[52] Historians believe the quote attributed to Wilson originated with Dixon, who was relentless in publicizing the film. After controversy over the film had grown, Wilson wrote that he disapproved of the "unfortunate production".[50]

Besides having the film screened at the White House, Dixon persuaded all nine justices of the Supreme Count to attend a screening of The Birth of a Nation as well as many members of Congress.[53] With the help of the Navy Secretary, Josephus Daniels, Dixon was able to meet the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, Edward Douglass White.[53] Initially Justice White was not interested in seeing the film, but when Dixon told him it was the "true story" of Reconstruction and the Klan's role in "saving the South", White, recalling his youth in Louisiana, jumped to attention and said: "I was a member of the Klan, sir".[53] With White agreeing to see the film, the rest of the Supreme Court followed. Dixon was clearly rattled and upset by criticism by African-Americans that the film version of his books was projecting hatred against them, and wanted the endorsement of many powerful men as possible to offset such criticism.[17] Dixon always vehemently denied having anti-black prejudices—despite the way his books promoted white supremacy—and stated: "My books are hard reading for a Negro, and yet the Negroes, in denouncing them, are unwittingly denouncing one of their greatest friends".[54]

In a letter sent on May 1, 1915, to Joseph P. Tumulty, the press secretary to President Wilson, Dixon wrote: "The real purpose of my film was to revolutionize Northern sentiments by a presentation of history that would transform every man in the audience into a good Democrat...Every man who comes out of the theater is a Southern partisan for life!"[48] In a letter to President Wilson sent on September 5, 1915, Dixon boasted: "This play is transforming the entire population of the North and the West into sympathetic Southern voters. There will never be an issue of your segregation policy".[48] Dixon was alluding to the fact that Wilson upon becoming president in 1913 had imposed segregation on federal workplaces in Washington D.C. while reducing the number of black employees through demotion or dismissal.[55]

Reception

Audience reaction

The Birth of a Nation was very popular, despite the film's controversy; it was unlike anything that American audiences had ever seen before.[57] The Los Angeles Times called it "the greatest picture ever made and the greatest drama ever filmed".[58] It became a national cultural phenomenon: merchandisers made Ku-Klux hats and kitchen aprons, and ushers dressed in white Klan robes for openings. In New York there were Klan-themed balls, and in Chicago that Halloween, thousands of college students dressed in robes for a massive Klan-themed party.[59]

The Reverend Charles Henry Parkhurst defended the film against the charge of racism by saying that it "was exactly true to history" by depicting freedmen as they were, and therefore it was a "compliment to the black man" by showing how far black people had "advanced" since Reconstruction.[56] Critic Dolly Dalrymple wrote that, "when I saw it, it was far from silent… incessant murmurs of approval, roars of laughter, gasps of anxiety, and outbursts of applause greeted every new picture on the screen".[60] One man viewing the film was so moved by the scene where Flora Cameron flees Gus to avoid being raped that he took out his handgun and began firing at the screen in an effort to help her.[60] Katherine DuPre Lumpkin recalled watching the film as an 18 year-old in 1915 in her 1947 autobiography The Making of a Southerner: "Here was the black figure—and the fear of the white girl—though the scene blanked out just in time. Here were the sinister men the South scorned and the noble men the South revered. And through it all the Klan rode. All around me people sighed and shivered, and now and then shouted or wept, in their intensity."[61]

Box office performance

The box office gross of The Birth of a Nation is not known, and was long subject to exaggeration.[62] When it opened tickets were sold at premium prices; the film played at the Liberty Theater in New York City for 44 weeks with tickets priced at $2.20 (equivalent to $53 in 2017).[63] By the end of 1917, Epoch reported to its shareholders cumulative receipts of $4.8 million,[64] and Griffith's own records put Epoch's worldwide earnings from the film at $5.2 million as of 1919,[65] although the distributor's share of the revenue at this time was much lower than the exhibition gross. In the biggest cities, Epoch negotiated with individual theater owners for a percentage of the box office; elsewhere, the producer sold all rights in a particular state to a single distributor (an arrangement known as "state's rights" distribution).[66] The film historian Richard Schickel says that under the state's rights contracts, Epoch typically received about 10% of the box office gross—which theater owners often underreported—and concludes that "Birth certainly generated more than $60 million in box-office business in its first run".[64]

By 1940 Time magazine estimated the film's cumulative gross rental (the distributor's earnings) at approximately $15 million.[67] For years Variety had the gross rental listed as $50 million, but in 1977 repudiated the claim and revised its estimate down to $5 million.[64] It is not known for sure how much the film has earned in total, but producer Harry Aitken put its estimated earnings at $15–18 million in a letter to a prospective investor in a proposed sound version.[65] It is likely the film earned over $20 million for its backers, and generated $50–100 million in box office receipts.[4] In a 2015 Time article, Richard Corliss estimated the film had earned the equivalent of $1.8 billion adjusted for inflation, a milestone that at the time had only been surpassed by Titanic (1997) and Avatar (2009) in nominal earnings.[68]

Sequel and spin-offs

D. W. Griffith made a film in 1916, called Intolerance, partly in response to the criticism that The Birth of a Nation received. Griffith made clear within numerous interviews that the film's title and main themes were chosen in response to those who he felt had been intolerant to The Birth of a Nation.[69] A sequel called The Fall of a Nation was released in 1916. It was the first sequel in film history.[70] The film was directed by Thomas Dixon, Jr., who adapted it from his novel of the same name. Despite its success in the foreign market, the film was not a success among American audiences,[71] and is now a lost film.[72] In 1918, an American silent drama film directed by John W. Noble called The Birth of a Race was released as a direct response to The Birth of a Nation.[73] The film was an ambitious project by producer Emmett Jay Scott to challenge Griffith's film and tell another side of the story, but was ultimately unsuccessful.[74]

In 1920, African-American filmmaker Oscar Micheaux released Within Our Gates, a response to The Birth of a Nation. Within Our Gates depicts the hardships faced by African-Americans during the era of Jim Crow laws.[75] The film was remixed in 2004 as Rebirth of a Nation, a live cinema experience by DJ Spooky at the Lincoln Center, and has toured at many venues around the world including Acropolis of Athens as a live cinema "remix". The remix version was also presented at the Paula Cooper Gallery in New York.[76] Quentin Tarantino has said that he made his film Django Unchained (2012) to counter the falsehoods of The Birth of a Nation.[77]

Ideology and accuracy

The film remains controversial due to its interpretation of American history. University of Houston historian Steven Mintz summarizes its message as follows: Reconstruction was a disaster, blacks could never be integrated into white society as equals, and the violent actions of the Ku Klux Klan were justified to reestablish honest government.[78] The South is portrayed as a victim. The first overt mentioning of the war is the scene in which Abraham Lincoln signs the call for the first 75,000 volunteers. However, the first aggression in the Civil War, made when the Confederate troops fired on Fort Sumter in 1861, is not mentioned in the film.[79] The film suggested that the Ku Klux Klan restored order to the postwar South, which was depicted as endangered by abolitionists, freedmen, and carpetbagging Republican politicians from the North. This reflects the so-called Dunning School of historiography.[80] The film is slightly less extreme than the books upon which it is based, in which Dixon misrepresented Reconstruction as a nightmarish time when black men ran amok, storming into weddings to rape white women with impunity.[81]

The film portrayed President Abraham Lincoln as a friend of the Confederacy, and refers to him as "the Great Heart".[82] The two romances depicted in the film, Phil Stoneman with Margaret Cameron and Ben Cameron with Elsie Stoneman, reflect Griffith's retelling of history. The couples are used as a metaphor, representing the film's broader message of the need for the reconciliation of the North and South to defend white supremacy.[83] Among both couples, there is an attraction that forms before the war, stemming from the friendship between their families. With the war, however, both families are split apart, and their losses culminate in the end of the war with the defense of white supremacy. One of the intertitles clearly sums up the message of unity: "The former enemies of North and South are united again in defense of their Aryan birthright."[84]

The film further reinforced the popular picture held by whites, especially in the South, of Reconstruction as a disaster. In his 1929 book The Tragic Era: The Revolution After Lincoln, the respected historian Claude Bowers treated The Birth of a Nation as a factually accurate account of Reconstruction.[85] In The Tragic Era, Bowers presented every black politician in the South as corrupt, portrayed Republican Representative Thaddeus Stevens as a vicious "race traitor" intent upon making blacks the equal of whites, and praised the Klan for "saving civilization" in the South.[85] Bowers wrote about black empowerment that the worst sort of "scum" from the North like Stevens "inflamed the Negro's egoism and soon the lustful assaults began. Rape was the foul daughter of Reconstruction!"[85] The American historian John Hope Franklin wrote that not only did Bowers treat The Birth of a Nation as accurate history, but his version of history seemed to be drawn from The Birth of a Nation.[85] Some historians, such as E. Merton Coulter in his The South Under Reconstruction (1947), maintained the Dunning School view after World War II. Today, the Dunning School position is largely seen as a product of anti-black racism of the early 20th century, by which many Americans held that black Americans were unequal as citizens. Coulter in The South During Reconstruction, which again treated The Birth of a Nation as historically correct, and painted a vivid picture of "black beasts" running amok, encouraged by alcohol-sodden, corrupt and vengeful black Republican politicians.[85] Franklin wrote that as recently as the 1970s that the popular journalist Alistair Cooke in his books and TV shows was still essentially following the version of history set out by The Birth of a Nation, noting that Cooke had much sympathy with the suffering of whites in Reconstruction while having almost nothing to say about the suffering of blacks or about how African-Americans were stripped of almost all their rights after 1877.[85]

Veteran film reviewer Roger Ebert wrote:

... stung by criticisms that the second half of his masterpiece was racist in its glorification of the Ku Klux Klan and its brutal images of blacks, Griffith tried to make amends in Intolerance (1916), which criticized prejudice. And in Broken Blossoms he told perhaps the first interracial love story in the movies—even though, to be sure, it's an idealized love with no touching.[86]

Despite some similarities between the Congressman Stoneman character and Rep. Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania, Rep. Stevens did not have the family members described and did not move to South Carolina during Reconstruction. He died in Washington, D.C. in 1868. However, Stevens' biracial housekeeper, Lydia Hamilton Smith, was considered his common-law wife, and generously provided for in his will.[87]

In the film, Abraham Lincoln is portrayed in a positive light due to his belief in conciliatory postwar policies towards southern whites. The president's views are directly contrasted by Austin Stoneman, a character shown in a negative light who acts as an antagonist. The assassination of Lincoln leads to the effective transition between the war and reconstruction, both of which are represented by the two acts of the film.[88] In including the assassination, the film also establishes to the audience that the plot of the movie has historical basis.[89] Franklin wrote the film's depiction of Reconstruction as a hellish time when black freedmen ran amok, raping and killing whites with impunity until the Klan stepped in is not supported by the facts.[90] Franklin wrote that most freed slaves continued to work for their former masters in Reconstruction for the want of a better alternative, and though relations between freedmen and their former masters were not friendly, very few freedmen sought revenge against the people who had held them in chains.[40] The character of Silas Lynch has no basis in fact, and during the Reconstruction no black or mulatto men served as the lieutenant governor of South Carolina.[90]

The depictions of mass Klan paramilitary actions do not seem to have historical equivalents, although there were incidents in 1871 where Klan groups traveled from other areas in fairly large numbers to aid localities in disarming local companies of the all-black portion of the state militia under various justifications, prior to the eventual Federal troop intervention, and the organized Klan's continued activities as small groups of "night riders".[91]

The civil rights movement and other social movements created a new generation of historians, such as scholar Eric Foner, who led a reassessment of Reconstruction. Building on W.E.B. DuBois' work but also adding new sources, they focused on achievements of the African-American and white Republican coalitions, such as establishment of universal public education and charitable institutions in the South and extension of suffrage to black men. In response, the Southern-dominated Democratic Party and its affiliated white militias had used extensive terrorism, intimidation and outright assassinations to suppress African-American leaders and voting in the 1870s and to regain power.[92]

Significance

Released in 1915, The Birth of a Nation has been credited as groundbreaking among its contemporaries for its innovative application of the medium of film. According to the film historian Kevin Brownlow, the film was "astounding in its time" and initiated "so many advances in film-making technique that it was rendered obsolete within a few years".[93] The content of the work, however, has received widespread criticism for its blatant racism. Film critic Roger Ebert writes:

Certainly The Birth of a Nation (1915) presents a challenge for modern audiences. Unaccustomed to silent films and uninterested in film history, they find it quaint and not to their taste. Those evolved enough to understand what they are looking at find the early and wartime scenes brilliant, but cringe during the postwar and Reconstruction scenes, which are racist in the ham-handed way of an old minstrel show or a vile comic pamphlet.[94]

Mary Pickford said: "Birth of a Nation was the first picture that really made people take the motion picture industry seriously".[95] The film held the mantle of the highest grossing film until it was overtaken by Gone with the Wind, another film about the Civil War and Reconstruction.[96][97] In 1992, the United States Library of Congress deemed the film "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" and selected it for preservation in the National Film Registry. Despite its controversial story, the film has been praised by film critics such as Ebert, who said: "The Birth of a Nation is not a bad film because it argues for evil. Like Riefenstahl's Triumph of the Will, it is a great film that argues for evil. To understand how it does so is to learn a great deal about film, and even something about evil."[94]

According to a 2002 article in the Los Angeles Times, the film facilitated the refounding of the Ku Klux Klan in 1915.[98] History.com similarly states that "There is no doubt that Birth of a Nation played no small part in winning wide public acceptance" for the KKK, and that throughout the film "African Americans are portrayed as brutish, lazy, morally degenerate, and dangerous."[99] David Duke used the film to recruit Klansmen in the 1970s.[100]

American Film Institute recognition

- AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movies (1997) – #44

In 2013, the American critic Richard Brody wrote The Birth of a Nation was :

...a seminal commercial spectacle but also a decisively original work of art—in effect, the founding work of cinematic realism, albeit a work that was developed to pass lies off as reality. It's tempting to think of the film's influence as evidence of the inherent corruption of realism as a cinematic mode—but it's even more revealing to acknowledge the disjunction between its beauty, on the one hand, and, on the other, its injustice and falsehood. The movie's fabricated events shouldn't lead any viewer to deny the historical facts of slavery and Reconstruction. But they also shouldn't lead to a denial of the peculiar, disturbingly exalted beauty of Birth of a Nation, even in its depiction of immoral actions and its realization of blatant propaganda. The worst thing about The Birth of a Nation is how good it is. The merits of its grand and enduring aesthetic make it impossible to ignore and, despite its disgusting content, also make it hard not to love. And it's that very conflict that renders the film all the more despicable, the experience of the film more of a torment—together with the acknowledgment that Griffith, whose short films for Biograph were already among the treasures of world cinema, yoked his mighty talent to the cause of hatred (which, still worse, he sincerely depicted as virtuous).[101]

Brody also argued that Griffith unintentionally undercut his own thesis in the film, citing the scene before the Civil War when the Cameron family offers up lavish hospitality to the Stoneman family who travel pass mile after mile of slaves working the cotton fields of South Carolina to reach the Cameron home-maintaining that a modern audience can see that the wealth of the Camerons comes from the slaves forced to do back-breaking work picking the cotton.[102] Likewise, Brody argued that the scene where people in South Carolina celebrate the Confederate victory at the Battle of Bull Run by dancing around the "eerie flare of a bonfire" which imply "a dance of death", foreshadowing the destruction of Sherman's March that was to come.[101] In the same way, Brody wrote that the scene where the Klan dumps Gus's body off at the doorstep of Lynch is meant to have the audience cheering, but modern audiences find the scene "obscene and horrifying".[101] Finally, Brody argued that the end of the film, where the Klan prevents defenseless African-Africans from exercising their right to vote by pointing guns at them today seems "unjust and cruel".[101]

In an article for The Atlantic, film critic Ty Burr deemed The Birth of a Nation the most influential film in history while criticizing its portrayal of black men as savage.[103] Richard Corliss of Time wrote that Griffith "established in the hundreds of one- and two-reelers he directed a cinematic textbook, a fully formed visual language, for the generations that followed. More than anyone else—more than all others combined—he invented the film art. He brought it to fruition in The Birth of a Nation." Corliss praised the film's "brilliant storytelling technique" and noted that "The Birth of a Nation is nearly as antiwar as it is antiblack. The Civil War scenes, which consume only 30 minutes of the extravaganza, emphasize not the national glory but the human cost of combat. ... Griffith may have been a racist politically, but his refusal to find uplift in the South's war against the Union—and, implicitly, in any war at all—reveals him as a cinematic humanist."[68] In his review of The Birth of a Nation in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die, Jonathan Kline writes that "with countless artistic innovations, Griffith essentially created contemporary film language ... virtually every film is beholden to [The Birth of a Nation] in one way, shape or form. Griffith introduced the use of dramatic close-ups, tracking shots, and other expressive camera movements; parallel action sequences, crosscutting, and other editing techniques". He added that "the fact that The Birth of a Nation remains respected and studied to this day-despite its subject matter-reveals its lasting importance."[104] The film holds a 100% approval rating on Rotten Tomatoes.[105]

New opening titles on re-release

One famous part of the film was added by Griffith only on the second run of the film[106] and is missing from most online versions of the film (presumably taken from first run prints).[107]

These are the second and third of three opening title cards which defend the film. The added titles read:

A PLEA FOR THE ART OF THE MOTION PICTURE:

We do not fear censorship, for we have no wish to offend with improprieties or obscenities, but we do demand, as a right, the liberty to show the dark side of wrong, that we may illuminate the bright side of virtue – the same liberty that is conceded to the art of the written word – that art to which we owe the Bible and the works of Shakespeare

and

If in this work we have conveyed to the mind the ravages of war to the end that war may be held in abhorrence, this effort will not have been in vain.

Various film historians have expressed a range of views about these titles. To Nicholas Andrew Miller, this shows that "Griffith's greatest achievement in The Birth of a Nation was that he brought the cinema's capacity for spectacle... under the rein of an outdated, but comfortably literary form of historical narrative. Griffith's models... are not the pioneers of film spectacle... but the giants of literary narrative".[108] On the other hand, S. Kittrell Rushing complains about Griffith's "didactic" title-cards,[109] while Stanley Corkin complains that Griffith "masks his idea of fact in the rhetoric of high art and free expression" and creates film which "erodes the very ideal" of liberty which he asserts.[110]

Home media and restorations

For many years, The Birth of a Nation was poorly represented in home media and restorations. This stemmed from several factors, one of which was the fact that Griffith and others had frequently reworked the film, leaving no definitive version. According to the silent film website Brenton Film, many home media releases of the film consisted of "poor quality DVDs with different edits, scores, running speeds and usually in definitely unoriginal black and white".[111]

One of the earliest high-quality home versions was film preservationist David Shepard's 1992 transfer of a 16mm print for VHS and laserdisc release via Image Entertainment. A short documentary, The Making of The Birth of a Nation, newly produced and narrated by Shepard, was also included. Both were released on DVD by Image in 1998 and the UK's Eureka Entertainment in 2000.[111]

In the UK, Photoplay Productions restored the Museum of Modern Art's 35mm print that was the source of Shepard's 16 mm print, though they also augmented it with extra material from the British Film Institute. It was also given a full orchestral recording of the original Breil score. Though broadcast on Channel 4 television and theatrically screened many times, Photoplay's 1993 version was never released on home video.[111]

Shepard's transfer and documentary were reissued in the US by Kino Video in 2002, this time in a 2-DVD set with added extras on the second disc. These included several Civil War shorts also directed by D.W. Griffith.[111] In 2011, Kino prepared a HD transfer of a 35 mm negative from the Paul Killiam Collection. They added some material from the Library of Congress and gave it a new compilation score. This version was released on Blu-ray by Kino in the US, Eureka in the UK (as part of their "Masters of Cinema" collection) and Divisa Home Video in Spain.[111]

In 2015, the year of the film's centenary, Photoplay Productions' Patrick Stanbury, in conjunction with the British Film Institute, carried out the first full restoration. It mostly used new 4K scans of the LoC's original camera negative, along with other early generation material. It, too, was given the original Breil score and featured the film's original tinting for the first time since its 1915 release. The restoration was released on a 2-Blu-ray set by the BFI, alongside a host of extras, including many other newly restored Civil War-related films from the period.[111]

In popular culture

- The Birth of a Nation's reverent depiction of the Klan was lampooned in Mel Brooks' Blazing Saddles (1974).[112]

- Ryan O'Neal's character in Peter Bogdanovich's Nickelodeon (1976) attends the premiere of The Birth of a Nation, and realizes that it will change the course of American cinema.[112]

- Clips from Griffith's film are shown in

- Robert Zemeckis' Forrest Gump (1994),[113]

- The closing montage of Spike Lee's Bamboozled (2000)[75]

- Lee's BlacKkKlansman (2018)[114]

- Director Kevin Willmott's mockumentary C.S.A.: The Confederate States of America (2004) portrays a imagined history where the Confederacy won the Civil War. It shows part of an imagined Griffith film, The Capture of Dishonest Abe, which resembles The Birth of a Nation and was supposedly adapted from Thomas Dixon's The Yankee .[115]

- In Justin Simien's Dear White People (2014), Sam (Tessa Thompson) screens a short film called The Rebirth of a Nation which portrays white people wearing whiteface while criticizing Barack Obama.[75]

- In 2016, Nate Parker produced and directed the film The Birth of a Nation, based on Nat Turner's slave rebellion; Parker clarified:

I've reclaimed this title and re-purposed it as a tool to challenge racism and white supremacy in America, to inspire a riotous disposition toward any and all injustice in this country (and abroad) and to promote the kind of honest confrontation that will galvanize our society toward healing and sustained systemic change.[116]

- Dinesh D'Souza's 2016 film Hillary's America: The Secret History of the Democratic Party depicts President Wilson and his cabinet viewing The Birth of a Nation in the White House before a Klansman comes out of the screen and into the real world.[117]

- The title of D'Souza's 2018 film Death of a Nation: Can We Save America a Second Time? is a reference to Griffith's film.[117]

See also

- List of films featuring slavery

- List of films with a 100% rating on Rotten Tomatoes, a film review aggregator website

Notes

- ↑ Runtime depends on projection speed ranging 16 to 24 frames per second

References

- ↑ "D. W. Griffith: Hollywood Independent". Cobbles.com. June 26, 1917. Archived from the original on August 24, 2013. Retrieved July 3, 2013.

- ↑ "THE BIRTH OF A NATION (U)". Western Import Co. Ltd. British Board of Film Classification. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved August 20, 2013.

- 1 2 Hall, Sheldon; Neale, Stephen (2010). Epics, spectacles, and blockbusters: a Hollywood history. Contemporary Approaches to Film and Television. Wayne State University Press. p. 270 (note 2.78). ISBN 978-0-8143-3697-7.

In common with most film historians, he estimates that The Birth of Nation cost "just a little more than $100,000" to produce...

- 1 2 Monaco, James (2009). How to Read a Film:Movies, Media, and Beyond. Oxford University Press. p. 262. ISBN 978-0-19-975579-0.

The Birth of a Nation, costing an unprecedented and, many believed, thoroughly foolhardy $110,000, eventually returned $20 million and more. The actual figure is hard to calculate because the film was distributed on a "states' rights" basis in which licenses to show the film were sold outright. The actual cash generated by The Birth of a Nation may have been as much as $50 million to $100 million, an almost inconceivable amount for such an early film.

- ↑ Gallen, Ira H. & Seymour Stern (2014). D.W. Griffith's 100th Anniversary The Birth of a Nation Archived February 7, 2018, at the Wayback Machine.. Victoria, BC, Canada: FriesenPress. p. 1. ISBN 9781460236536.

- ↑ MJ Movie Reviews – Birth of a Nation, The (1915) by Dan DeVore Archived July 7, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Armstrong, Eric M. (February 26, 2010). "Revered and Reviled: D.W. Griffith's 'The Birth of a Nation'". The Moving Arts Film Journal. Archived from the original on May 29, 2010. Retrieved April 13, 2010.

- 1 2 ""The Birth of a Nation" Sparks Protest". Mass Moments. Archived from the original on May 12, 2013. Retrieved July 3, 2013.

- ↑ "Top Ten – Top 10 Banned Films of the 20th century – Top 10 – Top 10 List – Top 10 Banned Movies – Censored Movies – Censored Films". Alternativereel.com. Archived from the original on May 12, 2012. Retrieved July 3, 2013.

- ↑ Stokes 2007, p. 111

- ↑ The Worst Thing About "Birth of a Nation" Is How Good It Is: The New Yorker Archived May 20, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. retrieved May 19, 2014

- ↑ "The Birth of a Nation (1915)". filmsite.org. Archived from the original on September 3, 2011.

- ↑ ...(the) portrayal of "Austin Stoneman" (bald, clubfoot; mulatta mistress, etc.) made no mistaking that, of course, Stoneman was Thaddeus Stevens..." Robinson, Cedric J.; Forgeries of Memory and Meaning. University of North Carolina, 2007; p. 99.

- ↑ Garsman, Ian; "The Tragic Era Exposed." Archived April 24, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Website: Reel American History; Lehigh University Digital Library, 2011–2012; Accessed January 23, 2013.

- ↑ Griffith followed the then-dominant Dunning School or "Tragic Era" view of Reconstruction presented by early 20th-century historians such as William Archibald Dunning and Claude G. Bowers. Stokes 2007, pp. 190–191.

- ↑ Leistedt, Samuel J.; Linkowski, Paul (January 2014). "Psychopathy and the Cinema: Fact or Fiction?". Journal of Forensic Sciences. American Academy of Forensic Sciences. 59 (1): 167–174. doi:10.1111/1556-4029.12359. PMID 24329037. Archived from the original on January 22, 2014. Retrieved January 17, 2014.

- 1 2 3 Franklin, John Hope "The Birth of a Nation: Propaganda as History" pages 417–434 from The Massachusetts Review Volume 20, No. 3, Autumn 1979 page 421.

- ↑ Lynskey, Dorian (March 31, 2015). "Still lying about history". Slate. Retrieved February 27, 2018.

- ↑ Franklin, John Hope "The Birth of a Nation: Propaganda as History" pages 417–434 from The Massachusetts Review Volume 20, No. 3, Autumn 1979page 421.

- ↑ Norton, Mary Beth (2015). A People and a Nation, Volume II: Since 1865, Brief Edition. Cengage Learning. p. 487. ISBN 1-305-14278-0.

- 1 2 3 Stokes, Melvyn (2007). D.W. Griffith's the Birth of a Nation: A History of "the Most Controversial Motion Picture of All Time". Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. pp. 105, 122, 124, 178. ISBN 978-0-19-533678-8.

- ↑ Franklin, John Hope "The Birth of a Nation: Propaganda as History" pages 417–434 from The Massachusetts Review Volume 20, No. 3, Autumn 1979 pages 422–423.

- ↑ Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Community Development Project. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Retrieved January 2, 2018.

- ↑ Seelye, Katharine Q. "When Hollywood's Big Guns Come Right From the Source", The New York Times, June 10, 2002.

- ↑ Moreland, George M. (January 18, 1925). "Rambling in Mississippi". The Memphis Commercial Appeal.

- ↑ Dirks, Tim, The Birth of a Nation, filmsite.org Archived September 3, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved May 27, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 Hickman 2006, p. 77.

- ↑ Hickman 2006, pp. 68–69.

- 1 2 Hickman 2006, p. 78.

- 1 2 Marks, Martin Miller (1997). Music and the Silent Film : Contexts and Case Studies, 1895–1924. Oxford University Press. pp. 127–135. ISBN 978-0-19-536163-6.

- ↑ Qureshi, Bilal (September 20, 2018). "The Anthemic Allure Of 'Dixie,' An Enduring Confederate Monument".

- ↑ Eder, Bruce. "Birth of a Nation [Original Soundtrack]". AllMusic. All Media Network, LLC. Retrieved February 6, 2014.

- ↑ Capps, Kriston (May 23, 2017). "Why Remix The Birth of a Nation?". The Atlantic. Retrieved February 28, 2018.

- ↑ Copeland, David (2010). The Media's Role in Defining the Nation: The Active Voice. Peter Lang Publisher. p. 168.

- ↑ NAACP – Timeline Archived January 5, 2010, at WebCite

- ↑ Nerney, Mary Childs. "An NAACP Official Calls for Censorship of The Birth of a Nation". History Matters. Archived from the original on May 24, 2015. Retrieved May 9, 2015.

- 1 2 Stokes 2007, p. 432.

- 1 2 Franklin, John Hope "The Birth of a Nation: Propaganda as History" pages 417–434 from The Massachusetts Review Volume 20, No. 3, Autumn 1979 page 426.

- ↑ Lehr, Dick (October 6, 2016). "When 'Birth of a Nation' sparked a riot in Boston". The Boston Globe. Retrieved February 28, 2018.

- 1 2 Franklin, John Hope "The Birth of a Nation: Propaganda as History" pages 417–434 from The Massachusetts Review Volume 20, No. 3, Autumn 1979 page 427.

- ↑ Gallen, Ira H. & Stern Seymour. D.W. Griffith's 100th Anniversary The Birth of a Nation (2014) p.47f.

- ↑ Gaines, Jane M. (2001). Fire and Desire: Mixed-Race Movies in the Silent Era. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 334.

- ↑ Christensen, Terry (1987). Reel Politics, American Political Movies from Birth of a Nation to Platoon. New York: Basil Blackwell Inc. p. 19. ISBN 0-631-15844-8.

- 1 2 3 4 Rylance, Mark "Breech Birth: The Receptions To D.W. Griffith's The Birth Of A Nation" page 1-20 from Australasian Journal of American Studies, Volume 24, No. 2, December 2005 page 15.

- ↑ Mayer, David (2009). Stagestruck Filmmaker: D.W. Griffith & the American Theatre. University of Iowa Press. p. 166. ISBN 1587297906.

- 1 2 Rylance, Mark "Breech Birth: The Receptions To D.W. Griffith's The Birth Of A Nation" page 1-20 from Australasian Journal of American Studies, Volume 24, No. 2, December 2005 page 16.

- ↑ Lennig, Arthur (April 2004). "Myth and Fact: The Reception of The Birth of a Nation". Film History. Archived from the original on December 22, 2014. Retrieved February 16, 2016.

- 1 2 3 Franklin, John Hope "The Birth of a Nation: Propaganda as History" pages 417–434 from The Massachusetts Review Volume 20, No. 3, Autumn 1979 page 430.

- ↑ Franklin, John Hope "The Birth of a Nation: Propaganda as History" pages 417–434 from The Massachusetts Review Volume 20, No. 3, Autumn 1979 pages 430–431.

- 1 2 Woodrow Wilson to Joseph P. Tumulty, April 28, 1915 in Wilson, Papers, 33:86.

- ↑ McEwan, Paul (2015). The Birth of a Nation. London: Palgrave. pp. 80–81. ISBN 978-1-84457-657-9.

- ↑ Letter from J. M. Tumulty, secretary to President Wilson, to the Boston branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, quoted in Link, Wilson.

- 1 2 3 Franklin, John Hope "The Birth of a Nation: Propaganda as History" pages 417–434 from The Massachusetts Review Volume 20, No. 3, Autumn 1979 page 425.

- ↑ Franklin, John Hope "The Birth of a Nation: Propaganda as History" pages 417–434 from The Massachusetts Review Volume 20, No. 3, Autumn 1979 page 424.

- ↑ Yellin, Eric S. (2013). Racism in the Nation's Service: Government Workers and the Color Line in Woodrow Wilson's America Archived February 7, 2018, at the Wayback Machine.. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina. p. 127. ISBN 9781469607207

- 1 2 Rylance, Mark "Breech Birth: The Receptions To D.W. Griffith's The Birth Of A Nation" page 1-20 from Australasian Journal of American Studies, Volume 24, No. 2, December 2005 pages 11–12.

- ↑ McEwan, Paul (2015). The Birth of a Nation. London: Palgrave. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-84457-657-9.

- ↑ Rylance, Mark "Breech Birth: The Receptions To D.W. Griffith's The Birth Of A Nation" page 1-20 from Australasian Journal of American Studies Volume 24, No. 2, December 2005 page 1.

- ↑ "A 1905 Silent Movie Revolutionizes American Film—and Radicalizes American Nationalists". Southern Hollows podcast. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- 1 2 Rylance, Mark "Breech Birth: The Receptions To D.W. Griffith's The Birth Of A Nation" page 1-20 from Australasian Journal of American Studies, Volume 24, No. 2, December 2005 page 3.

- ↑ Leiter, Andrew (2004). "Thomas Dixon, Jr.: Conflicts in History and Literature". Documenting the American South. Archived from the original on February 28, 2017. Retrieved July 21, 2017.

- ↑ Aberdeen, J. A. Distribution: States Rights or Road Show" Archived March 20, 2015, at the Wayback Machine., Hollywood Renegades Archive. Retrieved May 2, 2014.

- ↑ Thomas Doherty (February 8, 2015). "'The Birth of a Nation' at 100: "Important, Innovative and Despicable" (Guest Column)". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved February 8, 2015.

- 1 2 3 Schickel, Richard (1984). D.W. Griffith: An American Life. Simon and Schuster. p. 281. ISBN 0-671-22596-0. Archived from the original on January 6, 2017.

- 1 2 Wasko, Janet (1986). "D.W. Griffiths and the banks: a case study in film financing". In Kerr, Paul. The Hollywood Film Industry: A Reader. Routledge. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-7100-9730-9.

Various accounts have cited $15 to $18 million profits during the first few years of release, while in a letter to a potential investor in the proposed sound version, Aitken noted that a $15 to $18 million box-office gross was a 'conservative estimate'. For years Variety has listed The Birth of a Nation's total rental at $50 million. (This reflects the total amount paid to the distributor, not box-office gross.) This 'trade legend' has finally been acknowledged by Variety as a 'whopper myth', and the amount has been revised to $5 million. That figure seems far more feasible, as reports of earnings in the Griffith collection list gross receipts for 1915–1919 at slightly more than $5.2 million (including foreign distribution) and total earnings after deducting general office expenses, but not royalties, at about $2 million.

- ↑ Kindem, Gorham Anders (2000). The international movie industry. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press. p. 314. ISBN 0-8093-2299-4. Archived from the original on January 6, 2017.

- ↑ "Show Business: Record Wind". Time. February 19, 1940. Archived from the original on February 2, 2010. Retrieved April 29, 2014.

- 1 2 Corliss, Richard (March 3, 2015). "D.W. Griffith's The Birth of a Nation 100 Years Later: Still Great, Still Shameful". Time. Retrieved March 4, 2018.

- ↑ McEwan, Paul (2015). The Birth of a Nation (BFI Film Classics). London: BFI/Palgrave Macmillan. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-84457-657-9.

- ↑ Williams, Gregory Paul. The Story of Hollywood: An Illustrated History. p. 87. Archived from the original on February 7, 2018.

- ↑ Slide, Anthony (2004). American Racist: The Life and Films of Thomas Dixon. University Press of Kentucky. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-8131-2328-8. Archived from the original on January 6, 2017.

- ↑ Slide, Anthony (2004). "American Racist: The Life and Films of Thomas Dixon (review)". Project MUSE. Retrieved September 16, 2018.

- ↑ Kemp, Bill (February 7, 2016). "Notorious silent movie drew local protests". The Pantagraph. Archived from the original on February 8, 2016. Retrieved April 11, 2016.

- ↑ Stokes 2007, p. 166

- 1 2 3 Clark, Ashley (March 5, 2015). "Deride the lightning: assessing The Birth of a Nation 100 years on". The Guardian. Retrieved February 24, 2018.

- ↑ "Rebirth of a Nation at Paula Cooper Gallery". Paulacoopergallery.com. June 18, 2004. Archived from the original on April 1, 2012. Retrieved July 3, 2013.

- ↑ Brody, Richard. "The Worst Thing About "Birth of a Nation" Is How Good It Is". The New Yorker. Retrieved February 26, 2018.

- ↑ UG.edu Archived December 12, 2005, at the Wayback Machine., Digital History.

- ↑ Stokes 2007, p. 184.

- ↑ Stokes 2007, pp. 190–91.

- ↑ Leiter, Andrew (2004). "Thomas Dixon, Jr.: Conflicts in History and Literature". Documenting the American South. Archived from the original on February 28, 2017. Retrieved July 21, 2017.

- ↑ Stokes 2007, p. 188.

- ↑ "The Birth of a Nation: The Significance of Love, Romance, and Sexuality". Weebly. March 6, 2015. Archived from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved August 22, 2015.

- ↑ Salter, Richard C. (October 2004). "The Birth of a Nation as American Myth". The Journal of Religion and Film. Vol. 8, No. 2. Archived from the original on June 22, 2015. Retrieved August 22, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Franklin, John Hope "The Birth of a Nation: Propaganda as History" pages 417–434 from The Massachusetts Review Volume 20, No. 3, Autumn 1979 pages 432.

- ↑ Ebert, Roger (January 23, 2000). "Great Movies: 'Broken Blossoms'". Rogerebert.suntimes.com. Archived from the original on October 4, 2012. Retrieved July 3, 2013.

- ↑ Marc Egnal, Clash of Extremes, 2009.

- ↑ BoothieBarn (June 15, 2013). "The Assassination in "The Birth of a Nation"". BoothieBarn. Archived from the original on July 15, 2017. Retrieved June 22, 2017.

- ↑ University, Library and Technology Services, Lehigh. "Reel American History – Films – List". digital.lib.lehigh.edu. Archived from the original on October 15, 2015. Retrieved June 22, 2017.

- 1 2 Franklin, John Hope "The Birth of a Nation: Propaganda as History" pages 417–434 from The Massachusetts Review Volume 20, No. 3, Autumn 1979 pages 427–428.

- ↑ West, Jerry Lee. The Reconstruction Ku Klux Klan in York County, South Carolina, 1865–1877 (2002) p. 67

- ↑ Nicholas Lemann, Redemption: The Last Battle of the Civil War. New York: Farrar Straus and Giroux, 2006, p. 150-154

- ↑ Brownlow, Kevin (1968). The Parade's Gone By.... University of California Press. p. 78. ISBN 0520030680.

- 1 2 Ebert, Roger (March 30, 2003). "The Birth of a Nation (1915)". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on February 24, 2011. Retrieved February 21, 2011.

- ↑ Howe, Herbert (January 1924). "Mary Pickford's Favorite Stars and Films". Photoplay. New York: Photoplay Publishing Company. Retrieved September 4, 2015.

- ↑ Finler, Joel Waldo (2003). The Hollywood Story. Wallflower Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-1-903364-66-6.

- ↑ Kindem, Gorham Anders. The international movie industry.

- ↑ Hartford-HWP.com Archived February 1, 2017, at the Wayback Machine., A Painful Present as Historians Confront a Nation's Bloody Past.

- ↑ "Birth of A Nation Opens". history.com. A+E Networks. Archived from the original on November 29, 2016.

- ↑ "100 Years Later, What's The Legacy Of 'Birth Of A Nation'?". NPR. February 8, 2015. Retrieved February 26, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Brody, Richard (February 1, 2013). "The Worst Thing About "Birth of a Nation" Is How Good It Is". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on February 8, 2016. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

- ↑ Brody, Richard (February 1, 2013). "The Worst Thing About "Birth of a Nation" Is How Good It Is". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on February 8, 2016. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

- ↑ "What Was the Most Influential Film in History?". The Atlantic. March 2017. Retrieved February 26, 2018.

- ↑ Schneider, Steven Jay, ed. (2014). 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die. Quintessence Editions (7th ed.). Hauppauge, New York: Barron's Educational Series. p. 24. ISBN 978-1844037339. OCLC 796279948.

- ↑ "The Birth of a Nation". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 14 December 2014.

- ↑ Richard Schickel (1984). D. W. Griffith: An American Life. New York: Limelight Editions, p. 282

- ↑ This includes the one at the Internet Movie Archive and the Google video copy Archived August 13, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. and Veoh Watch Videos Online | The Birth of a Nation | Veoh.com Archived June 9, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.. However, of multiple YouTube copies one which has the full opening titles is DW GRIFFITH THE BIRTH OF A NATION PART 1 1915 on YouTube

- ↑ Miller, Nicholas Andrew (2002). Modernism, Ireland and the erotics of memory. Cambridge University Press. p. 226. ISBN 0-521-81583-5.

- ↑ Rushing, S. Kittrell (2007). Memory and myth: the Civil War in fiction and film from Uncle Tom's cabin to Cold mountain. Purdue University Press. p. 307. ISBN 1-55753-440-3.

- ↑ Corkin, Stanley (1996). Realism and the birth of the modern United States:cinema, literature, and culture. University of Georgia Press. pp. 144–145. ISBN 0-8203-1730-6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "The Birth of a Nation: Controversial Classic Gets a Definitive New Restoration". Brenton Film. Archived from the original on February 25, 2016. Retrieved February 23, 2016.

- 1 2 Lumenick, Lou (February 7, 2015). "Why 'Birth of a Nation' is still the most racist movie ever". New York Post. Retrieved February 26, 2018.

- ↑ Isenberg, Nancy; Burnstein, Andrew (February 17, 2011). "Still lying about history". Salon. Retrieved February 26, 2018.

- ↑ Edelstein, David (August 11, 2018). "Review: Spike Lee's provocative "BlacKkKlansman"". CBS News. Retrieved August 12, 2018.

- ↑ Brody, Richard (February 15, 2017). ""C.S.A.: The Confederate States of America," a Faux Documentary Skewers Real White Supremacy". The New Yorker. Retrieved February 26, 2018.

- ↑ Rezayazdi, Soheil (January 25, 2016). "Five Questions with the Birth of a Nation director Nate Parkr". Filmmaker magazine. Archived from the original on January 28, 2016.

- 1 2 Rizov, Vadim (May 25, 2017). ""Hitler was liberal" is just one insight offered by Dinesh D'Souza's fraudulent Death Of A Nation". The A.V. Club. Retrieved August 4, 2018.

Bibliography

- Addams, Jane, in Crisis: A Record of Darker Races, X (May 1915), 19, 41, and (June 1915), 88.

- Bogle, Donald. Toms, Coons, Mulattoes, Mammies and Bucks: An Interpretive History of Blacks in American Films (1973).

- Brodie, Fawn M. Thaddeus Stevens, Scourge of the South (New York, 1959), p. 86–93. Corrects the historical record as to Dixon's false representation of Stevens in this film with regard to his racial views and relations with his housekeeper.

- Chalmers, David M. Hooded Americanism: The History of the Ku Klux Klan (New York: 1965), p. 30 *Cook, Raymond Allen. Fire from the Flint: The Amazing Careers of Thomas Dixon (Winston-Salem, N.C., 1968).

- Franklin, John Hope. "Silent Cinema as Historical Mythmaker". In Myth America: A Historical Anthology, Volume II. 1997. Gerster, Patrick, and Cords, Nicholas. (editors.) Brandywine Press, St. James, NY. ISBN 978-1-881089-97-1

- Franklin, John Hope, "Propaganda as History" pp. 10–23 in Race and History: Selected Essays 1938–1988 (Louisiana State University Press, 1989); first published in The Massachusetts Review, 1979. Describes the history of the novel The Clan and this film.

- Franklin, John Hope, Reconstruction After the Civil War (Chicago, 1961), p. 5–7.

- Hickman, Roger. Reel Music: Exploring 100 Years of Film Music (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2006).

- Hodapp, Christopher L., and Alice Von Kannon, Conspiracy Theories & Secret Societies For Dummies (Hoboken: Wiley, 2008) p. 235–6.

- Korngold, Ralph, Thaddeus Stevens. A Being Darkly Wise and Rudely Great (New York: 1955) pp. 72–76. corrects Dixon's false characterization of Stevens' racial views and of his dealings with his housekeeper.

- Leab, Daniel J., From Sambo to Superspade (Boston, 1975), p. 23–39.

- New York Times, roundup of reviews of this film, March 7, 1915.

- The New Republica, II (March 20, 1915), 185

- Poole, W. Scott, Monsters in America: Our Historical Obsession with the Hideous and the Haunting (Waco, Texas: Baylor, 2011), 30. ISBN 978-1-60258-314-6

- Simkins, Francis B., "New Viewpoints of Southern Reconstruction", Journal of Southern History, V (February 1939), pp. 49–61.

- Stokes, Melvyn (2007), D. W. Griffith's The Birth of a Nation: A History of "The Most Controversial Motion Picture of All Time", New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-804436-4 . The latest study of the film's making and subsequent career.

- Williamson, Joel, After Slavery: The Negro in South Carolina During Reconstruction (Chapel Hill, 1965). This book corrects Dixon's false reporting of Reconstruction, as shown in his novel, his play and this film.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Birth of a Nation. |

- The Birth of a Nation on IMDb

- The Birth of a Nation: Controversial Classic Gets a Definitive New Restoration Detailed Brenton Film article by Patrick Stanbury on his 2015 restoration, including a history of the film on home video

- A 1905 Silent Movie Revolutionizes American Film — and Radicalizes American Nationalists; episode of the Southern Hollows history podcast

- The Birth of a Nation at 100 discussion on the BFI's YouTube channel

- The Birth of a Nation is available for free download at the Internet Archive

- The Birth of a Nation at the TCM Movie Database

- The Birth of a Nation at AllMovie

- The Birth of a Nation at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Birth of a Nation on Roger Ebert's list of great movies

- Souvenir Guide for The Birth of a Nation, hosted by the Portal to Texas History