Scent of a Woman (1992 film)

| Scent of a Woman | |

|---|---|

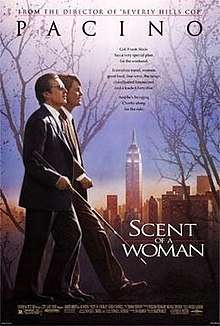

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Martin Brest |

| Produced by | Martin Brest |

| Screenplay by | Bo Goldman |

| Suggested by | |

| Based on |

Il buio e il miele by Giovanni Arpino |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Thomas Newman |

| Cinematography | Donald E. Thorin |

| Edited by |

|

Production company |

City Light Films |

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 156 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $31 million[1] |

| Box office | $134.1 million |

Scent of a Woman is a 1992 American drama film produced and directed by Martin Brest that tells the story of a preparatory school student who takes a job as an assistant to an irritable, blind, medically retired Army officer. The film is a remake of Dino Risi's 1974 Italian film Profumo di donna, adapted by Bo Goldman from the novel Il buio e il miele (Italian: Darkness and Honey) by Giovanni Arpino and from the 1974 screenplay by Ruggero Maccari and Dino Risi. The film stars Al Pacino and Chris O'Donnell, with James Rebhorn, Philip Seymour Hoffman and Gabrielle Anwar.

Pacino won the Academy Award for Best Actor for his performance and the film was nominated for Best Director, Best Picture and Best Screenplay Based on Material Previously Produced or Published. The film won three major awards at the Golden Globe Awards: Best Adapted Screenplay, Best Actor and Best Motion Picture – Drama.[2]

The film was shot primarily around New York state, and also on location at Princeton University, at the Emma Willard School, an all-girls school in Troy, New York, and at the Ethical Culture Fieldston School in New York City.

Plot

Charlie Simms is a student at the Baird School, an exclusive New England prep school. Unlike most of his peers, Charlie was not born into a wealthy family, and attends the school on a scholarship. To pay for a flight home to Oregon for Christmas, Charlie accepts a temporary job over Thanksgiving weekend looking after retired Army Ranger Lieutenant Colonel Frank Slade, whom Charlie discovers to be a cantankerous, blind alcoholic.

Charlie and George Willis, Jr., another student at the Baird School, witness three students setting up a prank that publicly humiliates the headmaster, Mr. Trask. Incensed over the prank, Trask quickly learns of the two student witnesses and presses Charlie and George to divulge the names of the perpetrators. Once George has left the office, Trask offers Charlie a bribe: a letter of recommendation that would virtually guarantee his acceptance to Harvard. Charlie remains silent, but is conflicted about what to do.

Shortly after Charlie arrives, Frank unexpectedly whisks Charlie off on a trip to New York City. Frank reserves a room at the Waldorf-Astoria. During dinner at the Oak Room, Frank glibly states the goals of the trip, which involve enjoying luxurious accommodations in New York before committing suicide. Charlie is taken aback and does not know if Frank is serious.

They pay an uninvited visit to Frank's brother's home in White Plains for Thanksgiving dinner. Frank is an unpleasant surprise for the family, as he deliberately provokes everyone and the night ends in acrimony. During this time, the cause of Frank's blindness is also revealed: he was juggling live hand grenades, showing off for a group of second lieutenants, and one of the grenades exploded.

As they return to New York City, Charlie tells Frank about his complications at school. Frank advises Charlie to inform on his classmates and go to Harvard, warning him that George will probably give in to the pressure to talk, and Charlie had better cash in before George does. Later at a restaurant, Frank is aware of Donna, a young woman waiting for her date. Although blind, Frank leads Donna in a spectacular tango ("Por una Cabeza") on the dance floor. That night, he hires a female escort.

Deeply despondent the next morning, Frank is initially uninterested in Charlie's proposals for something to do until he suggests they test drive a Ferrari Mondial t. Frank smooth-talks the initially-reluctant Ferrari dealership salesman into letting Charlie, who Frank says is his son, test-drive the car. Once on the road, Frank is unenthusiastic until Charlie allows him to drive, quickly getting the attention of a police officer. Once again being calm and charming in a potentially difficult situation, Frank talks the officer into letting them go without giving away his blindness.

When they return to the hotel, Frank sends Charlie out on a list of errands. Charlie initially leaves the room but quickly becomes suspicious. Charlie returns to find Frank in his full dress blues uniform, preparing to commit suicide with a pistol from which Charlie had made Frank promise to remove the bullets earlier. Frank simply says "I lied" as he loads the sidearm. Charlie intervenes and attempts to grab Frank's pistol. Frank, however, easily overpowers him, threatening to shoot Charlie before himself. They enter a tense fight, with both grappling for the gun; however, Frank backs down after Charlie bravely calms him. The two return to New England.

At school, Charlie and George are subjected to a formal inquiry in front of the entire student body and the student/faculty disciplinary committee. As Headmaster Trask is opening the proceedings, Frank unexpectedly returns to the school, joining Charlie on the auditorium stage for support. For his defense, George has enlisted the help of his wealthy father, using his poor vision as an excuse before naming all three of the perpetrators. When pressed for more details, George passes the burden to Charlie. Although struggling with his decision, Charlie gives no information, so Trask recommends Charlie's expulsion.

Frank cannot contain himself and launches into a passionate speech defending Charlie and questioning the integrity of a school that punishes students for defending their classmates and rewards those for snitching. Frank reveals that there was an attempt to buy Charlie's testimony and that regardless of whether his silence is right or wrong, Charlie refuses to sell anybody out to advance his future. Frank tells the committee that Charlie has shown integrity in his actions and insists they don't expel him because this is what great leaders are made of, and promises that if allowed to continue on, Charlie will make them proud in the future. After brief deliberations, the disciplinary committee decide to place the students named by George on probation, deny George of any accolades for his testimony and excuse Charlie from punishment, allowing him to have no further involvement in the proceedings. On this announcement, the hall erupts to thunderous applause from the students.

As Charlie escorts Frank to his limo, a female political science teacher, Christine Downes, who is part of the disciplinary committee, approaches him, commending him for his speech. Seeing a spark between them, Charlie tells Downes that Frank served on President Lyndon Johnson's staff. In their brief encounter, Frank deftly establishes Downes is single and surprises her by correctly identifying her perfume scent as Fleurs de Rocaille; they agree to get together sometime and "talk politics".

Charlie takes Frank home. The colonel walks towards his house and happily greets his niece's young children as Charlie watches by the limo.

Cast

- Al Pacino as Lieutenant Colonel Frank Slade

- Chris O'Donnell as Charlie Simms

- James Rebhorn as Mr. Trask

- Gabrielle Anwar as Donna

- Philip Seymour Hoffman as George Willis, Jr.

- Gene Canfield as Manny

- Richard Venture as William "W.R." Slade

- Bradley Whitford as Randy Slade

- June Squibb as Mrs. Hunsaker

- Frances Conroy as Christine Downes

- Rochelle Oliver as Gretchen Slade

- Tom Riis Farrell as Garry Slade

- Nicholas Sadler as Harry Havemeyer

- Todd Louiso as Trent Potter

- Matt Smith as Jimmy Jameson

- Ron Eldard as Officer Gore

- Margaret Eginton as Gail

- Sally Murphy as Karen Rossi

- Michael Santoro as Donny Rossi

- Julian and Max Stein as Willie Rossi

- Leonard Gaines as Freddie Bisco

Production

Scent of a Woman was filmed in the following US locations.[3]

- Brooklyn, New York City, New York

- Dumbo, Brooklyn, New York City, New York

- Emma Willard School, 285 Pawling Avenue, Troy, New York

- Hempstead House, Sands Point Preserve, 95 Middleneck Road, Port Washington, Long Island, New York (school)

- Kaufman Astoria Studios, 3412 36th Street, Astoria, Queens, New York City, New York (studio)

- Long Island, New York

- Manhattan, New York City, New York

- Newark Liberty International Airport, Newark, New Jersey

- New York City, New York

- Pierre Hotel, Fifth Avenue & 61st Street, Manhattan, New York City, New York (ballroom where Frank and Donna dance the tango)

- Port Washington, Long Island, New York

- Prince's Bay, Staten Island, New York City, New York

- Princeton, New Jersey

- Queens, New York City, New York

- Rockefeller College—Upper Madison Hall, Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey

- Staten Island, New York City, New York

- The Oak Room, The Plaza Hotel, 5th Avenue, Manhattan, New York City, New York (where Frank and Charlie have dinner)

- Troy, New York

- Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, 301 Park Avenue, Manhattan, New York City, New York

Pacino painstakingly researched his part in Scent of a Woman. To understand what it feels like to be blind, he met with clients of New York's Associated Blind, being particularly interested in hearing from those who had lost their sight due to trauma. Clients traced the entire progression for him—from the moment they knew they would never see again to the depression and through to acceptance and adjustment. The Lighthouse, also in New York, schooled him in techniques a blind person might use to find a chair and seat themselves, pour liquid from a bottle and light a cigar.[4]

Screenplay writer for Scent of a Woman, Bo Goldman, said, "If there is a moral to the film, it is that if we leave ourselves open and available to the surprising contradictions in life, we will find the strength to go on."[4]

Reception

Scent of a Woman holds an 88% approval rating on review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes,[5] and a score of 59 out of 100 on Metacritic, based on 14 critic reviews.[6]

Pacino won an Academy Award for Best Actor, the first of his career after four previous nominations, which is his eighth overall nomination.

Some criticized the film for its length.[7] Variety's Todd McCarthy said it "goes on nearly an hour too long".[8] Newsweek's David Ansen believes that the "two-character conceit doesn't warrant a two-and-a-half-hour running time".[9]

The film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 2005: AFI's 100 Years...100 Movie Quotes:

- 2006: AFI's 100 Years...100 Cheers – Nominated[11]

Box office

The film earned US$63,095,253 in the US and $71 million internationally, totaling $134,095,253 worldwide.[12][13][14]

See also

References

- ↑ Box Office Information for Scent of a Woman Archived 2013-06-28 at the Wayback Machine.. The Wrap. Retrieved April 4, 2013.

- ↑ Fox, David J. (1993-01-25). "Pacino Gives Oscar Derby a New Twist : Awards: Actor wins Golden Globe for role in 'Scent of a Woman,' which also wins as best dramatic picture, surprising Academy Awards competitors". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2010-11-14.

- ↑ "A Sight for Sore Eyes". Newsweek. 29 March 1992. Retrieved 2010-11-14.

- 1 2 Brest, Martin (director) (2006). "Production notes". Scent of a Woman (DVD). United Kingdom: Universal Pictures (UK).

- ↑ "Scent of a Woman". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 2012-03-23.

- ↑ Scent of a Woman on IMDb

- ↑ Wells, Jeffrey (1993-01-03). "LENGTH OF 'A WOMAN' : Minutes, Shminutes--Does It Play?". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2010-11-14.

- ↑ "Scent of a Woman". Variety. 1991-12-31. Retrieved 2010-11-14.

- ↑ "Not A Season To Be Jolly". Newsweek. Retrieved 2010-11-14.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Movie Quotes Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved 2016-08-14.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Cheers Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved 2016-08-14.

- ↑ Fox, David J. (1992-12-29). "Weekend Box Office Holiday Take a Nice Gift for the Studios". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2010-11-14.

- ↑ Fox, David J. (1993-01-26). "Weekend Box Office `Aladdin's' Magic Carpet Ride". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2010-11-18.

- ↑ Welkos, Robert W. (1993-02-02). "Weekend Box Office `Sniper' Takes Aim at `Aladdin'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2010-11-18.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Scent of a Woman |