Staten Island Railway

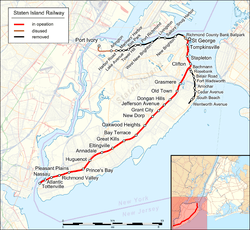

The Staten Island Railway (SIR) is the only rapid transit line in the New York City borough of Staten Island. It is operated by the Staten Island Rapid Transit Operating Authority (SIRTOA),[2] a unit of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Although the railway is considered a standard rail line, only the western portion of the North Shore Branch (which is used by freight) is connected to the national rail system.

SIR operates 24 hours a day, seven days a week with modified R44 New York City Subway cars,[3] and is run by the New York City Transit Authority, an agency of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority and operator of the New York City Subway. However, there is no direct rail link between the SIR and the subway system. SIR riders receive a free transfer to New York City Subway lines, and the line is included on official New York City Subway maps.[4] Commuters on the railway typically use the Staten Island Ferry to reach Manhattan; the line is accessible from within the Ferry Terminal, and most of its trains connect with the ferry.

The Staten Island Railway provides full-time local service between Saint George and Tottenville, along the east side of the borough. Although there is no subway service for residents of the western or northern Staten Island, light rail has been proposed for these corridors. The MTA is planning to implement bus rapid transit on the North Shore, and a study is underway to determine whether light rail should be implemented on Staten Island's West Shore. The line has a route bullet similar to other subway routes: the letters SIR in a blue circle. It is used on timetables, the MTA website and some signage,[lower-alpha 1] but not on trains. The line runs 24 hours a day every day of the year,[5] (since May 10, 2015, the overnight service is on a 30-minute headway[6][7]) and is one of only seven 24/7 mass-transit rail lines in the United States; the others are the PATCO Speedline, the Red and Blue Lines of the Chicago "L", the Green Line of the Minneapolis-St. Paul Metro, the PATH lines, and the New York City Subway.

In addition to full-time local service, the Staten Island Railway also runs a weekday peak-direction express service. On weekdays, express service to St. George is provided from 6:15 to 8:15 a.m. and to Tottenville from 7:01 to 8:01 a.m. and 4:01 to 7:51 p.m. Morning express trains run non-stop in both directions between New Dorp and St. George; afternoon express trains run non-stop southbound from St. George to Great Kills.[6] Express service is noted on trains by a red marker with the terminal and "Express" underneath it.[lower-alpha 2]

History

19th century

The Staten Island Rail Road was incorporated on August 2, 1851, after Perth Amboy and Staten Island residents petitioned for a Tottenville-to-Stapleton rail line. The railroad was financed with a loan from Cornelius "Commodore" Vanderbilt, the sole Staten Island-to-Manhattan ferry operator on the East Shore, his first involvement in a railroad.[8] The line was completed to Tottenville on June 2, 1860.[9]:7[10]:225 Many stations were named after large nearby farms, such as Garretson's and Gifford's. The stations at Eltingville and Annadale, whose namesakes (the Eltings family and Anna Seguine) were influential in constructing the rail line, were the most elaborate.[11]

Under the leadership of Commodore Vanderbilt's brother, Jacob H. Vanderbilt, the Staten Island Rail Road took over several independent ferries and train service improved.[11] The Staten Island Railway and ferry line made a modest profit until the explosion of the ferry Westfield at Whitehall Street Terminal on July 30, 1871.[9]:7[12]:36 By July 1872, the railroad and ferry were in receivership. On September 17, 1872, the company was sold to George Law in foreclosure.[8][10]:225–228[13]:462 The following April 1, the Staten Island Rail Road was transferred to the Staten Island Railway Company.[14]:1255

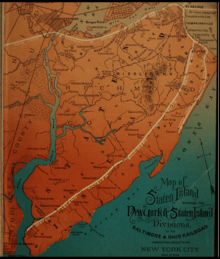

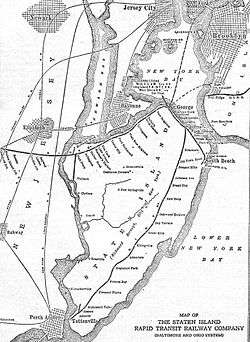

Erastus Wiman, known as "the duke of Staten Island," was one of its most prominent residents after he moved to a mansion on the island. By 1880 the railway was barely operational, and New York State sued (through Attorney General Hamilton Ward) to dissolve the company in May of that year.[10]:229[15] Wiman organized the Staten Island Rapid Transit Company (SIRT) on March 25, 1880, and partnered with the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad to build a large rail terminal on the island and centralize the six-to-eight ferry landings.[9]:7[10]:7[12]:37 He secured an extension on a land-purchase option from George Law by offering to name it "St. George" after him.[16]:4[17]:8

Construction of the Vanderbilt's Landing-to-Tompkinsville portion of the North Shore Branch began on March 17, 1884,[10]:230[12]:37[18] and the line opened for passenger service on August 1 of that year.[19] The lighthouse just above Tompkinsville impeded the line's extension to St. George but, after the SIRT lobbied for an act of Congress, construction of a two-track, 580-foot (180 m) tunnel under the lighthouse began in 1885 for about $190,000.[20]:690 The SIR was leased to the B&O for 99 years in 1885.[9]:7–8[10]:230[12]:37 Proceeds of the lease were used to complete the terminal at Saint George, pay for two miles of waterfront property, complete the Rapid Transit Railroad, build a bridge over the Kill Van Kull at Elizabethport, and build other terminal facilities.[21] The North Shore Branch opened for service on February 23, 1886, to Elm Park.[20]:690 The Saint George terminal opened on March 7, 1886, and all SIR lines were extended to the station.[10]:231[12]:37 On March 8, 1886, the South Beach Branch opened for passenger service to Arrochar.[8][10]:231[13]:463[22] The remainder of the North Shore Branch, to its terminus at Erastina, was opened in the summer of 1886.[9] The new lines opened by the B&O were known as the Staten Island Rapid Transit Railway, and the original line (from Clifton to Tottenville) was called the Staten Island Railway.[23]

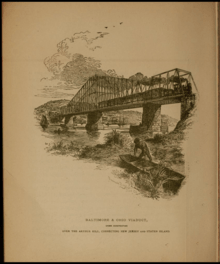

Several proposals were made by the B&O for a rail line between Staten Island and New Jersey. The accepted proposal was a 5.25-mile-mile (8.45 km) line from Arthur Kill to the Jersey Central at Cranford, through Union County and the communities of Roselle and Linden. Construction of the line began in 1889, and was finished later in the year.[9][24] Congress passed a law on June 16, 1886, authorizing the construction of a 500-foot (150 m) swing bridge over Arthur Kill, after three years of effort by Erastus Wiman.[12][25] The start of construction was delayed for nine months by the need for approval of the Secretary of War, and another six months due to an injunction by the State of New Jersey.[9] This required construction to continue through the harsh winter of 1888 because Congress had set a completion deadline of June 16, 1888, two years after signing the bill.[12] The bridge was completed three days early, on June 13, 1888 at 3 p.m.[8][13][26] The Arthur Kill Bridge was the world's largest drawbridge when it opened, and there were no fatalities in its construction.[25] On January 1, 1890, the first train operated from St. George Terminal to Cranford Junction.[9][27] When the Arthur Kill Bridge was completed, the United States War Department was unsuccessfully pressured by the Lehigh Valley and Pennsylvania Railroads to have the newly-built bridge replaced with a bridge with a different design; according to the railroads, it was an obstruction to navigation of the large numbers of coal barges past Holland Hook on Arthur Kill.[12][24]

In 1889, the South Beach Branch was extended from Arrochar to a new terminal at South Beach.[11] Eight years later, the terminal at Saint George (which served the railroad and the ferry to Manhattan) was completed.[10]

20th century

Improvements were made to the SIRT after the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) took control of the B&O in 1900. After its acquisition by the PRR, the B&O became profitable again.[24] On October 25, 1905, New York City took ownership of the ferry and terminals and evicted the B&O from the Whitehall Street terminal. The St. George Terminal was then built by the city for $2,318,720.[28]:29

In anticipation of a tunnel under the Narrows to Brooklyn and a connection there with the BMT Fourth Avenue Line of the New York City Subway, the SIRT electrified its lines with third rail power distribution and cars similar to those of the Brooklyn–Manhattan Transit Corporation (BMT).[29] The first electric train was operated on the South Beach Branch between South Beach and Fort Wadsworth on May 30, 1925, and the other branches were electrified by November of that year.[29][30][31]:7805 The promise of faster, more-reliable service with electrification spurred developers and other investors to purchase land along the SIRT lines to build housing for future residents of the island.[32] Electrification did not greatly increase traffic, and the tunnel was never built.[33] During the 1920s, a branch line along Staten Island's West Shore was built to haul building materials for the Outerbridge Crossing. The branch was cut back to a point south of the crossing after the bridge was built. The Gulf Oil Corporation opened a dock and tank farm along Arthur Kill in 1928; to serve it, the Travis Branch was built south from Arlington Yard into the marshes of the island's western shore to Gulfport.[9]:41[11][34]

| Year | Traffic |

|---|---|

| 1925 | 67 |

| 1944 | 81 |

| 1960 | 37 |

| 1967 | 38 |

The Port Richmond–Tower Hill viaduct, the nation's largest grade-crossing-elimination project, was completed on February 25, 1937. The viaduct, more than a mile long, spanned eight grade crossings on the SIRT's North Shore Branch and was the final part of a $6,000,000 grade-crossing-elimination project on the island which eliminated thirty-four crossings on its north and south shores.[35]

Freight and World War II traffic helped pay some of the SIRT's accumulated debt, and the line was briefly profitable in the 1940s. All East Coast military-hospital trains were handled by the SIRT during the war, and some trains stopped at Staten Island's Arlington station to transfer wounded soldiers to a large military hospital. The need to transport war materiel, POW trains and troops made the stretch of the Baltimore & New York Railway between Cranford Junction and Arthur Kill extremely busy. The B&O also operated special trains for important officials, such as Winston Churchill.[24] On June 25, 1946, a fire destroyed the St. George Terminal; three people were killed, twenty-two were injured and damage totaled $22 million.[10]:239[12] The fire destroyed the ferry terminal, the four slips used for service to Manhattan and the SIRT terminal.[36][37] Normal service was not restored until July 13, 1946, and a request for bids to build a temporary terminal was issued on August 21 of that year. On February 10, 1948, a replacement terminal was promised by Mayor William O'Dwyer. The new terminal opened on June 8, 1951, with ferry, bus and rail service in one building;[10]:240 portions of the new terminal were phased into service earlier.[38] It cost $23 million.[39]:55

The number of SIRT passengers decreased from 12.3 million in 1947 to 4.4 million in 1949 as passengers switched from the rail line to city-operated buses due to a bus-fare reduction.[40] On September 5, 1948, 237 of the line's 492 weekday trains were cut; express service would be reduced during rush hours, and all night trains after 1:29 a.m. would be cancelled. Thirty percent of the company's employees were laid off.[41][42] On September 7, 1948, Staten Island Borough President Cornelius Hall continued to rally against the SIRT cuts at a Public Service Commission hearing in Manhattan. Commuters testified that trains were missing ferry connections and being held at the St. George Terminal during rush hour to wait for double boatloads of passengers; the trains had previously pulled out after each ferry unloaded.[43] On September 13, 1948, the SIRT agreed to add four trains and extend the schedule of four others.[44] Nine days later the Interstate Commerce Commission allowed the SIRT to abandon the ferry it had operated for 88 years between Tottenville and Perth Amboy, New Jersey, and the ferry operation was transferred to Sunrise Ferries of Elizabeth, New Jersey on October 16.[45][46]

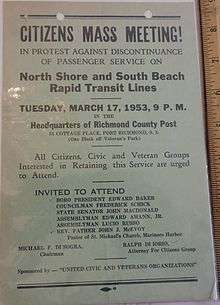

SIRT discontinued passenger service on the North Shore Branch (to Arlington) and the South Beach Branch (to Wentworth Avenue) at midnight on March 31, 1953 due to competition from city-operated buses; the South Beach Branch was abandoned shortly afterwards, and the North Shore Branch continued to carry freight.[47][48] By 1955, the third rails on both lines were removed.[9]:8 On September 7, 1954, SIRT applied to discontinue passenger service on the Tottenville Branch on October 7 of that year;[49] a large city subsidy allowed passenger service on the branch to continue.[8]

The Arthur Kill swing bridge was damaged by an Esso oil tanker in November 1957, and was replaced by a single-track, 558-foot (170 m) vertical-lift bridge in 1959.[24] The prefabricated, 2,000-ton bridge was floated into place.[9]:8 The new bridge could rise 135 feet (41 m) and, since it aided navigation on Arthur Kill, the federal government assumed 90 percent of the project's $11 million cost. Freight trains started crossing the bridge when it opened on August 25, 1959.[50]:349 The Travis Branch was extended in 1958 to a new Consolidated Edison power plant in Travis (on the West Shore), allowing coal trains from West Virginia to serve the plant.[9]:8 The B&O continued to invest in its properties in New Jersey and Staten Island into the late 1950s.[24]

SIRT lost money until the 1970s as it rebuilt stations between Jefferson Avenue and New Dorp. Rail traffic across the Arthur Kill Bridge dropped dramatically with the closing of Bethlehem Steel in 1960 and U.S. Gypsum in 1972. Operation of the Tottenville line was turned over to the Staten Island Rapid Transit Operating Authority (a division of the state's Metropolitan Transportation Authority) on July 1, 1971, and the line was purchased by the city of New York.[24] As part of the agreement, freight on the line would continue to be handled by the B&O.[24] The first six R44 cars (the same as the newest cars then in use on the subway lines in the other boroughs) were put into SIRT service on February 28, 1973, replacing the ME-1 cars which had been in service since 1925.[51] Between 1971 and 1973, a project began to extend the high-level platforms at six stations.[52]:11–12, 49, 52 A station-rebuilding program began in 1985, and the line's R44s were overhauled starting in 1987.[53]

The B&O became part of the larger C&O system in a merger with the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway, and the island's freight operation was renamed the Staten Island Railroad Corporation in 1971. The B&O and C&O became isolated from their other properties in New Jersey and Staten Island with the creation of Conrail on April 1, 1976 in a merger of bankrupt lines in the northeastern U.S. Their freight service now terminated in Philadelphia, but for several years afterward B&O locomotives and one B&O freight train a day ran to Cranford Junction. By 1973, the Jersey Central's car float yard was closed; however, the B&O's car-float operation was later brought back to Staten Island at Saint George Yard. This car-float operation was taken over by the New York Dock Railway in September 1979, and ended the following year. Only a few isolated industries on Staten Island used rail freight, and the yard at Saint George was essentially abandoned.[9]:9[24] The C&O system sold the Staten Island Railroad to the New York, Susquehanna & Western Railroad, owned by the Delaware Otsego Corporation, in April 1985 due to a lack of business.[47] The Susquehanna then embargoed the track east of Elm Park on the North Shore Branch, ending rail freight to Saint George. Procter & Gamble (the line's largest customer) closed in 1990, leading to a large drop in freight traffic. The last freight train crossed the bridge in 1990 and the operation ended on July 25, 1991, when the Arthur Kill Bridge was taken out of service. The North Shore Branch and the Arthur Kill Bridge were then taken over by CSX. The line and bridge were purchased in 1994 by the New York City Economic Development Corporation (NYCEDC), followed by a decade of false starts.[9]:9

SIRT was transferred from the New York City Transit Authority's Surface Transit Division to its Department of Rapid Transit on July 26, 1993,[54] and that year the Dongan Hills station became accessible under the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990.[55] MetroCards were accepted for fare payment at the St. George station beginning on March 31, 1994, and the station became the 50th MTA rapid transit station to accept them.[56] The Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) restored the line's original name on April 2 of that year as the MTA Staten Island Railway (SIR).[9]:9[57] On July 4, 1997, the MTA eliminated fares for travel between Tompkinsville and Tottenville as part of the year's "One City, One Fare" fare reductions.[58] United Transportation Union Local 1440, the union representing SIR employees, was concerned about the fare reduction in part because of an expected increase in ridership.[59][60] No turnstiles were installed at the other stations on the line, and passengers at St. George began paying when entering and exiting;[61] fares had previously been collected on board by the conductor.[62] The removal of fares was blamed for an immediate spike in crime along the line.[63] Three afternoon express trains were added to the schedule on April 7, 1999, nearly doubling the previous express service. The express trains skipped stops between St. George and Great Kills.[64] A new station building at Tompkinsville opened on January 20, 2010, with turnstiles installed to prevent passengers from exiting (free of charge) at Tompkinsville and walking the short distance to the St. George ferry terminal.[65][66]

Current use

Passenger service

.png)

Although the Staten Island Railway originally consisted of three lines, only the north-south Main Line is in passenger service. The terminus at St. George provides a direct connection with the Staten Island Ferry.[7] St. George has twelve tracks, ten of which are in service. Tottenville has a three-track yard, with two tracks on each side of a concrete station platform.[67]:102

The SIR resembles an outdoor line of the New York City Subway. Although the railway has been grade-separated from all roads since the 1960s, it runs more or less at street level for a brief stretch north of Clifton (between the Grasmere and Old Town stations) and from south of the Pleasant Plains station to Tottenville—the end of the line. It uses NYC Transit-standard 600 V DC third-rail power.[68] Rolling stock consists of modified R44 subway-type cars with headlight dimmers, electric windshield defrosters, Federal Railroad Administration (FRA)-compliant cab signals and horns, FRA regulation 223-required shatterproof glazing, and exterior-mounted grab rails near the side doors. The cars were built in early 1973, at the end of the R44 order of subway cars for New York City Transit, and were the last cars built by the St. Louis Car Company. Heavy maintenance is performed at NYCT's Clifton Shops, and any work unable to be done at Clifton requires the cars to be trucked over the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge to the subway's Coney Island Complex in Brooklyn. The right-of-way includes elevated, embankment and open-cut sections, and a tunnel near St. George.[67]:102–103

The last passenger trains on the railway's North Shore and South Beach Branches ran on March 31, 1953.[9]:8[47][48] The South Beach Branch right-of-way was removed from maps, and its tracks have been pulled up. A several-hundred-foot section of the easternmost portion of the North Shore Branch was reopened for passenger service to the Richmond County Bank Ballpark, home of the Staten Island Yankees minor-league baseball team, on June 24, 2001; the service was discontinued on June 18, 2010.[69]

Before 2007, the Staten Island Railway used Baltimore & Ohio Railroad-style color position light signals dating back to its B&O days. That year, a $72-million project to replace the old signal system was completed. The system was replaced with an FRA-compliant 100 Hz, track-circuit-based automatic train control (ATC) signal system. As part of the project, forty R44 subway cars and four locomotives were modified with onboard cab signaling equipment for ATC bi-directional movement. A new rail control center and backup control center were built as part of the project.[70]

Arthur Kill, an ADA-compliant station near the line's southern terminus, opened on January 21, 2017 after a number of delays. The station is between (and replaced) the Atlantic and Nassau stations, which were in the poorest condition of all the stations on the line.[71][72] The Arthur Kill station is able to accommodate a four-car train.[73] The MTA has provided parking for 150 automobiles across the street from the station. Ground was broken for the $15.3 million station on October 18, 2013.[74] Its builder, John P. Picone, received the contract on July 31, 2013.[75]

Only the Dongan Hills, St. George, Great Kills and Tottenville stations have been renovated to comply with the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990; these stations have elevators and/or ramps.[5][76] The Prince's Bay, Huguenot, Annadale, Great Kills and Dongan Hills stations have park-and-ride facilities.[6]

Sally Librera has been the railway's vice-president and chief officer since her appointment in May 2017.[77] The workforce, about 200 hourly employees, is represented by United Transportation Union Local 1440.[78]

Police

On June 1, 2005, the Staten Island Rapid Transit Police Department was disbanded and its 25 railroad police officers became part of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority Police. The MTA Police department was created in 1998 with the merger of the Long Island Rail Road Police and the Metro-North Railroad Police Department. The MTA Police Department then opened its newest patrol district, Police District #9, which began covering the Staten Island Railway.[79]

Fare

The cash fare is $2.75, the same fare as the New York City Subway and MTA Regional Bus Operations. Fares are paid on entry and exit only at St. George and Tompkinsville. Rides not originating or terminating at St. George or Tompkinsville are free. Fares are payable by MetroCard. Since the card enables free transfers for a continuous ride on the subway and bus systems, for many more riders there is effectively no fare for riding the SIR. Riders can also transfer between a Staten Island bus, the SIR and a Manhattan bus (or subway) near South Ferry.[80] Because of this, the SIR's 2001 farebox recovery ratio was 0.16; for every dollar of expense, 16 cents was recovered in fares (the lowest ratio of MTA agencies). The low farebox recovery ratio is part of the reason the MTA wants to merge the SIR with the subway: to simplify accounting and subsidy of (essentially) a single line.[81]

Before the 1997 introduction of "one-fare zone",[82] with the MetroCard's free transfers from the SIR to the subway system and MTA buses, fares were collected from passengers boarding at stops other than St. George by onboard conductors.[83] In the past, passengers had avoided paying the fare by exiting at Tompkinsville and walking a short distance to the St. George ferry terminal. The MTA installed turnstiles at Tompkinsville and a new station building, which opened on January 20, 2010.[65][66]

Freight service

During the early 2000s, plans to reopen the Staten Island Rapid Transit line in New Jersey were announced by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. Since the Central Railroad of New Jersey became a New Jersey Transit line, a new junction would be built to the former Lehigh Valley Railroad. So all New England and southern freight could pass through the New York metropolitan area, two rail tunnels from Brooklyn (one to Staten Island and the other to Greenville, New Jersey) were planned.[24] On December 15, 2004, a $72 million project to reactivate freight service on Staten Island and repair the Arthur Kill Vertical Lift Bridge was announced by the New York City Economic Development Corporation (NYCEDC) and the Port Authority. Projects on the Arthur Kill bridge included repainting the steel superstructure and rehabilitating its lift mechanism.[84] The freight-line connection from New Jersey to the Staten Island Railway was completed and became operational in part by the Morristown and Erie Railway, under contract with the State of New Jersey and other companies, in June 2006.[85]

The Arthur Kill Vertical Lift Bridge was renovated in 2006 and returned to regular service on April 2, 2007, sixteen years after it closed.[86] A portion of the North Shore Branch was rehabilitated, the Arlington Yard was expanded and 6,500 feet (1,981 m) of new track was laid along the Travis Branch to Fresh Kills as part of the project.[87] Soon after service resumed on the line, Mayor Michael Bloomberg commemorated the reactivation on April 17, 2007.[88] Service was provided by CSX Transportation, Norfolk Southern Railway and Conrail on the Travis Branch to haul waste from the Staten Island Transfer Station at Fresh Kills and ship container freight from the Howland Hook Marine Terminal and other industrial businesses. Tracks and overpasses remain on other, unused sections of the North Shore Branch.[89][90][91][92][93]

Future plans

Elected officials on Staten Island, including Diane Savino, have demanded the replacement of the railway's aging R44 cars.[94] Although the Metropolitan Transportation Authority initially planned to order R179s for the Staten Island Railway, it decided to overhaul R46s to replace the R44s.[95] The plan was dropped, and 75 R211S cars will replace the R44s.[96][97] In the meantime, the R44s are receiving intermittent rounds of scheduled maintenance to extend their usefulness until at least 2022-2023.[98][99]

Several proposals have been made to connect the SIR to the subway system, including the abandoned, unfinished Staten Island Tunnel and a line along the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge using B Division cars and loading gauge, but economic, political and engineering difficulties have prevented the bridge line from realization.[100] There is also discussion of rebuilding a Rosebank station, which would bridge the longest gap between two stations (Grasmere and Clifton). A Rosebank station existed on the railway's now-defunct South Beach Branch.[101]

Possible light rail and branch restoration

In a 2006 report, the Staten Island Advance explored the restoration of passenger service on 5.1 miles (8.2 km) of the North Shore Branch between St. George and Arlington. Completion of a study is necessary to qualify the project for an estimated $360 million. A preliminary study found that ridership could reach 15,000 daily.[102] U.S. Senator Chuck Schumer of New York requested $4 million of federal funding for a detailed feasibility study.[103] In 2012, the MTA released an analysis of North Shore transportation solutions which included proposals for the reintroduction of heavy rail, light rail or bus rapid transit using the North Shore line's right-of-way. Other options included system management, which would improve existing bus service, and the possibility of future ferry and water-taxi service. Bus rapid transit was preferred for its cost ($352 million in capital investment) and relative ease of implementation. In January 2018, the project had yet to receive funding.[104]:61 As part of the 2015–2019 MTA Capital Program, $4 million has been allocated for an analysis of light rail on Staten Island's West Shore.[105]

Branches and stations

Main Line stations

| Station service legend | |

|---|---|

| Stops all times | |

| Stops rush hours only | |

| Stops rush hours in the peak direction only | |

| Future station | |

| Time period details | |

| Station is compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act | |

| Station is compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act in the indicated direction only | |

| Elevator access to mezzanine only | |

- * Some local trains start at Huguenot during morning rush hours.

| Off-peak | Lcl | AM exp | PM exp | Station | Minutes from St. George[6] | Opened | Closed | Connections, notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| St. George Terminal |

0 | March 7, 1886[106] | ||||||

| Tompkinsville | 3 | July 31, 1884[8] | ||||||

| Stapleton | 5 | July 31, 1884[8] | ||||||

| Clifton | 7 | April 23, 1860[8] | Originally Vanderbilt's Landing; access via first three cars northbound[6] | |||||

| Grasmere | 10 | 1886 | ||||||

| Old Town | 12 | 1937 | Originally Old Town Road | |||||

| Dongan Hills |

14 | April 23, 1860[8] | Originally Garretson's | |||||

| Jefferson Avenue | 16 | 1937 | ||||||

| Grant City | 17 | April 23, 1860[8] | ||||||

| New Dorp | 19 | April 23, 1860[8] | ||||||

| Oakwood Heights | 21 | April 23, 1860[8] | Originally Richmond,[107] then Court House,[108] then Oakwood | |||||

| Bay Terrace | 23 | Early 1900s | Originally Whitlock | |||||

| Great Kills |

25 | April 23, 1860[8] | Southern terminus for select trains Originally Gifford's | |||||

| * | Eltingville | 27 | April 23, 1860[8] | |||||

| Woods of Arden | 1886 | c.1894-1895 | Closed | |||||

| * | Annadale | 29 | May 14, 1860[8] | |||||

| * | Huguenot | 31 | June 2, 1860[8] | Southern terminus for select northbound trains Originally Bloomingview, then Huguenot Park | ||||

| Prince's Bay | 33 | June 2, 1860[8] | Originally Lemon Creek, then Princes Bay | |||||

| Pleasant Plains | 35 | June 2, 1860[8] | ||||||

| Richmond Valley | 37 | June 2, 1860[8] | Access via first three cars[109] | |||||

| Nassau | (39) | c. 1924[8] | January 21, 2017[110] | Closed when Arthur Kill opened.[110] | ||||

| Arthur Kill |

39 | January 21, 2017[110] | Replacement for Nassau & Atlantic, which closed the same day[71] | |||||

| Atlantic | (40) | c.1909–1911[111] | January 21, 2017[110] | Closed when Arthur Kill opened.[110] | ||||

| Tottenville |

42 | June 2, 1860[8] |

Former stations

North Shore Branch

The North Shore Branch closed to passenger service at midnight on Tuesday, March 31, 1953.[8][112][113] A small portion of the western end is used for freight service as part of the ExpressRail intermodal network at the Howland Hook Marine Terminal. The network, which opened in 2007, connects to the Chemical Coast after crossing the Arthur Kill Vertical Lift Bridge.[88][114] A smaller eastern portion, which provided seasonal passenger service to the Richmond County Bank Ballpark station (where the Staten Island Yankees play, operated from June 24, 2001 to June 18, 2010.[115] In 2008, restoration was discussed along the mostly-abandoned 6.1-mile (9.8 km) line as part of the island's light-rail plan.[116] The North Shore Branch served Procter & Gamble, United States Gypsum, shipbuilders and a car float at Saint George Yard.[24]

| Miles | Name | Opened | Closed | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | St. George | March 7, 1886 | ||

| 0.1 | RCB Ballpark | June 24, 2001 | June 18, 2010[115] | |

| 0.7 | New Brighton | February 23, 1886 | March 31, 1953[113] | |

| 1.2 | Sailors' Snug Harbor | February 23, 1886 | March 31, 1953[113] | |

| 1.8 | Livingston | February 23, 1886 | March 31, 1953[113] | |

| 2.4 | West Brighton | February 23, 1886 | March 31, 1953[113] | |

| 3.0 | Port Richmond | February 23, 1886 | March 31, 1953[113] | |

| 3.4 | Tower Hill | February 23, 1886 | March 31, 1953[113] | |

| 3.9 | Elm Park | February 23, 1886 | March 31, 1953[113] | |

| 4.3 | Lake Avenue | 1937 | March 31, 1953[113] | |

| 4.6 | Mariners Harbor | Summer 1886 | March 31, 1953[113] | Originally named Erastina |

| 4.9 | Harbor Road | 1935–1937 | March 31, 1953[113] | |

| 5.2 | Arlington | 1889–1890 | March 31, 1953[113] | |

| 6.1 | Port Ivory | 1906 | 1948 |

South Beach Branch

The South Beach Branch opened on March 8, 1886 to Arrochar, and was extended to South Beach in 1889.[11][26] The branch closed at midnight on Tuesday, March 31, 1953.[112][113] It was abandoned and demolished, except for three segments: a concrete embankment at Clayton Street and Saint John's Avenue,[117] a trestle over Robin Road in Arrochar[118] and a filled-in bridge under McClean Avenue.[119][120] This 4.1-mile (6.6 km) line left the Main Line at 40°37′08″N 74°04′18″W / 40.61889°N 74.07167°W (south of the Clifton station), and was east of the Main Line. Although the right-of-way has been redeveloped, most of it is still traceable on maps; the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge toll plaza is on the former right-of-way.[121]

The Robin Road trestle is the only remaining intact trestle along the former line. Developers purchased the land on either side of its abutments during the early 2000s, and the developers, the New York City Department of Transportation, and the New York City Transit Authority all claimed ownership. Townhouses have been built on both sides of the trestle.[121][122]

| Miles | Name | Opened | Closed | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.0 | Bachmann | March 8, 1886 | 1937 | |

| 2.1 | Rosebank | March 8, 1886 | March 31, 1953[113] | |

| 2.5 | Belair Road | March 8, 1886 | March 31, 1953[113] | |

| 2.7 | Fort Wadsworth | March 8, 1886 | March 31, 1953[113] | |

| 3.2 | Arrochar | March 8, 1886 | March 31, 1953[113] | |

| 3.5 | Cedar Avenue | 1934[123] | March 31, 1953[113] | |

| 3.9 | South Beach | 1889[11] | March 31, 1953[113] | |

| 4.1 | Wentworth Avenue | 1925 | March 31, 1953[113] |

Freight lines

Mount Loretto Spur

The Mount Loretto Spur is an abandoned branch whose purpose was to serve the Mount Loretto Children's Home. The spur diverged from the Main Line south of Pleasant Plains.[9]:110 The B&O Railroad served the non-electrified branch, which had some industry and a passenger station, until 1950. Although its track was removed during the 1960s and 1970s, some ties were visible until the 1980s. A coal trestle is all that remains of the branch.[8]:15

West Shore Line

South of the Richmond Valley station, a non-electrified spur branched off the Tottenville-bound track (which once ran to Arthur Kill). The spur, built in 1928, was called the West Shore Line by the B&O Railroad and delivered building materials to the Outerbridge Crossing construction site near Arthur Kill.[124] Years later, the track was used to serve a scrapyard owned by the Roselli Brothers.[125] The track was intact to Page Avenue until 2013, with the right-of-way ballasted[126] and the switch in working condition to allow trains to be stored (evidenced by the fouling-point sign).[127] The rails are still present past the old connection, west of the right-of-way.[128] The track divided in two under Page Avenue, with the rails still in place.[129][130] The line's right-of-way, an easement on property owned by Nassau Metals, was later used by CSX.[129]:1-2 Although sections of the old tracks have been removed, others remain in the overgrowth.[131]

Travis Branch

The Travis Branch, from Arlington Yard to Fresh Kills, runs along the island's West Shore. The branch was built in 1928 to serve Gulf Oil along the Arthur Kill, south from Arlington Yard into the marshes to Gulfport. It was extended to Travis to serve the new Consolidated Edison power plant in 1957.[9]:47[34] In 2005, the branch was being renovated and was extended from the old Con Edison plant to the Staten Island Transfer Station at Fresh Kills; regular service to the transfer station began in April 2007.[88]

See also

Notes

References

- 1 2 "The MTA Network". mta.info. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Retrieved February 22, 2018.

- ↑ "Metropolitan Transportation Authority Description and Board Structure Covering Fiscal Year 2010" (PDF). mta.info. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. 2010. Retrieved August 10, 2017.

- ↑ Sansone, Gene (October 25, 2004). New York Subways: An Illustrated History of New York City's Transit Cars. JHU Press. p. 257. ISBN 9780801879227.

- ↑ "Subway Map" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. January 18, 2018. Retrieved January 18, 2018.

- 1 2 "MTA/New York City Transit- Staten Island Railway". mta.info. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Retrieved October 8, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "MTA Staten Island Railway Timetable, Effective October 4, 2015" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Retrieved June 24, 2018.

- 1 2 "The Railway and the Ferry Connection". mta.info. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. October 2015. Retrieved August 10, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 Leigh, Irvin; Matus, Paul (January 2002). "Staten Island Rapid Transit: The Essential History". thethirdrail.net. The Third Rail Online. Archived from the original on May 30, 2015. Retrieved June 27, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Pitanza, Marc (2015). Staten Island Rapid Transit Images of Rail. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4671-2338-9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Roess, Roger P.; Sansome, Gene (2013). The Wheels That Drove New York: A History of the New York City Transit System. Springer. ISBN 978-3-642-30484-2. Retrieved October 4, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Bommer, Edward. "History of the Staten Island Railway by Ed Bommer through correspondence". docs.google.com. Retrieved August 29, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Harwood, Herbert H. (2002). Royal Blue Line: The Classic B&O Train Between Washington and New York. JHU Press. ISBN 9780801870613. Retrieved November 17, 2015.

- 1 2 3 Morris, Ira (1900). Morris's Memorial History of Staten Island, New York. 2. Memorial Publishing Company.

- ↑ Report of the Public Service Commission For the First District of the State of New York For the Year Ending December 31, 1913. Public Service Commission. 1913.

- ↑ "A Railroad Charter in Peril". The New York Times. May 14, 1880. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- ↑ St. GEORGE HISTORIC DISTRICT STATEN ISLAND (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. July 19, 1994.

- ↑ Goldfarb, David; Ferreri, James G. (2009). St. George. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 9780738562520.

- ↑ "City and Suburban News; New-York. Brooklyn. Long Island. Staten Island. Westchester County. New-Jersey". The New York Times. March 18, 1884. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- ↑ "City and Suburban News; New-York. Brooklyn. Long Island. Staten Island. New-Jersey". The New York Times. August 13, 1884. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- 1 2 Preston, L. E. (1887). History of Richmond County (Staten Island), New York: From Its Discovery to the Present Time, Part 1. Memorial Publishing Company.

- ↑ "Affairs of Railroads; the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad to Enter New-York. Mr. Garrett Leases the Staten Island Rapid Transit Railroad and Will Connect His Road with That System". The New York Times. November 22, 1885. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- ↑ "Staten Island Improvements". The New York Times. September 1, 1888. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- ↑ Moody's Manual of Investments: American and Foreign: Transportation. Moody's Investors Service. 1905. Retrieved November 3, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Bommer, Edward (July 3, 2004). "The Baltimore & Ohio Railroad in New Jersey". jcrhs.org. Jersey Central Railway Historical Society Chapter. Retrieved December 17, 2015.

- 1 2 "The Largest Drawbridge: Completion of the Big Span Across the Arthur Kill" (PDF). The New York Times. June 14, 1888. Retrieved July 3, 2015.

- 1 2 "Staten Island Improvement" (PDF). The New York Times. September 1, 1888. Retrieved July 3, 2015.

- ↑ "Over The New Bridge: A Train Runs From Staten Island to New Jersey" (PDF). The New York Times. January 2, 1890. Retrieved July 3, 2015.

- ↑ Hilton, George Woodman (1964). The Staten Island Ferry. Howell-North Books.

- 1 2 "OPENS NEW SERVICE ON ELECTRIFIED LINE; Staten Island Marks End of Steam Locomotives on Perth Amboy Division. LYNCH LEADS CEREMONY Commends B. & O. for Prompt Action in Obeying the Law -- Galloway Asks Cooperation". The New York Times. July 2, 1925. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 13, 2017.

- ↑ "Electrical Rapid Transit Begins On Staten Island" (PDF). The New York Times. May 31, 1925. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

- ↑ Official Proceedings of the New York Railroad Club, Volume 36. New York Railroad Club. 1925.

- ↑ "Eltingville Celebrates Electrification of SIRT, 1925". Secret Staten Island. Archived from the original on February 1, 2013. Retrieved August 13, 2017.

- ↑ "Baltimore and Ohio to Operate on Staten Island" (PDF). The New York Times. October 23, 1895. Retrieved July 14, 2011.

- 1 2 Bommer, Edward. "West Shore Branch". Retrieved November 22, 2015.

- ↑ "Staten Island Opens Mile-Long Viaduct; Thirty-Four Grade Crossings Are Eliminated" (PDF). The New York Times. February 26, 1937. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

- ↑ "Staten Island Fire Wrecks Ferry Terminal, Kills 3; Damage Put at $2,000,000: 22 Go to Hospitals" (PDF). The New York Times. June 26, 1946. Retrieved July 5, 2015.

- ↑ "Staten Island Fire Still Smoldering: City Acts to Vote $3,000,000 to Start Work on Terminal Costing $12,000,000" (PDF). The New York Times. June 27, 1946. Retrieved July 5, 2015.

- ↑ Cudahy, Brian J. (January 1, 1990). Over and Back: The History of Ferryboats in New York Harbor. Fordham University Press. p. 282. ISBN 0-8232-1245-9. Retrieved October 12, 2015.

- ↑ Museum, Staten Island (September 1, 2014). Staten Island Ferry. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 9781439647066.

- ↑ "Staten Island–Laboratory Experiment In Socialized Transportation: how below-cost competition from money-losing city buses has made impossible continued private operation of rail passenger service in New York's island borough". Railway Age. Simmons-Boardman Publishing Company: 58–63. August 11, 1952 – via Google Books.

- ↑ "PSC Fails to Prevent S.I. Rail Service Cut" (PDF). The New York Times. September 3, 1948. Retrieved July 5, 2015.

- ↑ "Road Cuts Service On Staten Island: Non-Rush-Hour Schedules Are Reduced by 50 % – Some Night Trains Taken Off" (PDF). The New York Times. September 6, 1948. Retrieved July 5, 2015.

- ↑ "Staten Islanders Protest Train Cuts: Led by Borough President Hall, They Charge Overcrowding With Curtailed Service" (PDF). The New York Times. September 9, 1948. Retrieved July 5, 2015.

- ↑ "Train Service Added For Staten Island" (PDF). The New York Times. September 14, 1948. Retrieved July 5, 2015.

- ↑ "Ferry To Change Hands: Staten Island Rapid Transit Facility to be Run by Lessee" (PDF). The New York Times. September 23, 1948. Retrieved July 5, 2015.

- ↑ "Ferry Line To Change Hands" (PDF). The New York Times. September 30, 1948. Retrieved July 5, 2015.

- 1 2 3 Drury, George H. (1994). The Historical Guide to North American Railroads: Histories, Figures, and Features of more than 160 Railroads Abandoned or Merged since 1930. Waukesha, Wisconsin: Kalmbach Publishing. pp. 312–314. ISBN 0-89024-072-8.

- 1 2 "The Old Order Passeth: Rails Surrender To Roads: Passenger Runs on Two Lines of SIRT Will End at Midnight". Staten Island Advance. March 31, 1953. p. 1. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- ↑ Ingalls, Leonard (September 8, 1954). "Staten Island Line Would Cease Runs: Railway Renews Bid to End All Passenger Service–Rejects Transit Union Plan" (PDF). The New York Times. Retrieved October 11, 2015.

- ↑ Stover, John F. (1995). History of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. Purdue University Press. ISBN 9781557530660. Retrieved November 1, 2015.

- ↑ "S.I 'Toonerville Trolley' Gets New Cars" (PDF). The New York Times. March 1, 1973. Retrieved July 8, 2015.

- ↑ 1968-1973, the ten-year program at the halfway mark. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. 1973.

- ↑ "SIRT KEEPS ROLLING ALONG REBUILDING PROGRAM NEARING COMPLETION". Staten Island Advance. April 18, 1993. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ↑ "SIRT SWITCHED FROM ONE DIVISION TO ANOTHER T.A. REORGANIZATION LEAVES BUS SERVICE WITHOUT MANAGER". Staten Island Advance. July 27, 1993. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ↑ "ISLAND DISABLED SUBJECT OF SIRT STATION HEARING MTA TO DISCUSS DONGAN HILLS PLANS". Staten Island Advance. April 25, 1992. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ↑ "METROCARD CHRISTENED AT ST. GEORGE STATION TRANSIT OFFICIALS SAY FERRY IS NEXT IN LINE FOR NEW FARE SYSTEM Advance Photo by Robert Sollett". Staten Island Advance. April 1, 1994. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ↑ "IT'S ISLAND RAILWAY, NOT RAPID TRANSIT MTA HAS NEW NAMES FOR ITS TRANSPORTATION SYSTEMS Out with the old In with the new". Staten Island Advance. April 2, 1994. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ↑ "Staten Island Railway traverses our borough TRANSPORTATION". Staten Island Advance. April 29, 2001. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ↑ "S.I. RAILWAY: MORE MAY RIDE TRAIN FOR FREE AND THAT HAS WORKERS WORRIED". Staten Island Advance. April 10, 2017. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ↑ "S.I. RAILWAY: MORE MAY RIDE TRAIN FOR FREE AND THAT HAS WORKERS WORRIED". Staten Island Advance. April 10, 1997. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ↑ "FREE RIDES TO MOST STATIONS ON STATEN ISLAND RAILWAY ONLY THOSE WHO ENTER AND LEAVE AT ST. GEORGE PAY FOR THE COMMUTE". Staten Island Advance. April 26, 1998. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ↑ "RAILWAY RIDERS WILL PAY ONLY AT ST. GEORGE ON-BOARD COLLECTION WILL BE ELIMINATED AS LINE JOINS THE CITY'S ONE-FARE SYSTEM JULY 4". Staten Island Advance. May 14, 1997. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ↑ "Free ride to commit a crime Elimination of fare for most on the Staten Island Railway allows trouble-causing youths to get on and off at will". Staten Island Advance. August 22, 1999. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ↑ "3 additional express runs begin tonight on Railway New trains almost double the evening express service from St. George to Great Kills". Staten Island Advance. April 7, 1999. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- 1 2 Mooney, Jake (September 7, 2008). "Soon, It Won't Even Pay to Walk". The New York Times. Retrieved October 8, 2015.

- 1 2 "Fare-saving walk now less of a bargain for Staten Island commuters". silive.com. August 28, 2008. Retrieved August 11, 2017.

- 1 2 Dougherty, Peter (2018). Tracks of the New York City Subway 2018 (16th ed.). Dougherty.

- ↑ "Staten Island Line to Electrify". Electric Railway Journal. 63 (20): 776–777. May 17, 1924 – via archive.org.

- ↑ "Evaluation of 2010 Service Reductions" (PDF). mta.info. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. September 23, 2011. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- ↑ "Staten Island Signal Modernization" (PDF). Transit Resources. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- 1 2 "Groundbreaking for New MTA Staten Island Railway Arthur Kill Station in Tottenville". mta.info. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. October 18, 2013. Archived from the original on February 26, 2014. Retrieved August 11, 2017.

- ↑ "Capital Program Oversight Committee Meeting June 2016" (PDF). mta.info. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. June 17, 2016. Retrieved June 17, 2016.

- ↑ "Staten Island Railway Celebrates 1st New Station in 20 Years". mta.info. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. January 20, 2017. Retrieved April 22, 2018.

- ↑ Stein, Mark D. (October 18, 2013). "Photos, video: Groundbreaking for new Arthur Kill Staten Island Railway station, set to open in 2015". silive.com. Archived from the original on 2013-10-19. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- ↑ Stein, Mark D. (September 27, 2012). "It's official: New Staten Island Railway access for Tottenville". silive.com. Archived from the original on 2012-10-05. Retrieved October 8, 2015.

- ↑ "MTA Guide to Accessible Transit". mta.info. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Retrieved April 22, 2018.

- ↑ "Sally Librera Appointed Chief Officer, MTA Staten Island Railway". mta.info. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. May 25, 2017. Retrieved May 26, 2017.

- ↑ "Proudly serving the riders of the MTA Staten Island Railway (SIRTOA)!". 1440.utu.org. UTU Local 1440. Archived from the original on February 28, 2015. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- ↑ "MTA Staten Island Railway 2006 Preliminary Budget July Financial Plan 2006-2009" (PDF). mta.info. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. July 2006. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ↑ "MTA Staten Island Railway Fare and Transfer Information". mta.info. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Retrieved October 8, 2015.

- ↑ "MTA to merge agencies into five companies". progressiverailroading.com. October 11, 2002. Retrieved March 7, 2009.

- ↑ Giuliani, Rudolph (June 29, 1997). "Archives of Rudolph W. Giuliani Mayor's Message". nyc.gov. Retrieved December 5, 2011.

- ↑ Linder, Bernard (January 2018). "Staten Island's 157-Year-Old Railroad" (PDF). Bulletin. Electric Railroaders' Association. 61 (1): 1.

- ↑ "Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg and Governor George E. Pataki Announce Reactivation of Staten Island Railroad". nyc.gov. Office of the Mayor. December 15, 2004. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- ↑ "New Jersey short line to operate county-owned lines". progressiverailroading.com. July 8, 2002. Retrieved March 7, 2009.

- ↑ "New York City welcomes back Staten Island Railroad". progressiverailroading.com. April 19, 2007. Retrieved March 7, 2009.

- ↑ "Staten Island Railroad Reactivation". New York City Economic Development Corporation. April 17, 2007. Retrieved March 7, 2009.

- 1 2 3 "Mayor Bloomberg Officially Reactivates the Staten Island Railroad" (Press release). New York City Mayor's Office. April 17, 2007. Retrieved January 28, 2010. Archived on December 23, 2007.

- ↑ "North Shore Alternatives Analysis: Rail Alignment Drawings Arlington-St. George" (PDF). mta.info. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. September 2010. Retrieved July 20, 2015.

- ↑ "North Shore Alternatives Analysis: Public Meeting THURSDAY, APRIL 22, 2010 7:00 p.m." (PDF). zetlin.com. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. April 22, 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 6, 2015. Retrieved July 31, 2015.

- ↑ "NYCT NORTH SHORE ALTERNATIVES ANALYSIS: Alternatives Analysis Report" (PDF). mta.info. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. August 2012. Retrieved July 20, 2015.

- ↑ "Feasibility Study of the North Shore Railroad Right-of-Way Project Assessment Report March 2004" (PDF). library.wagner.edu. Office of the Staten Island Borough President, Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, URS, SYSTRA,. March 2004. Retrieved August 6, 2015.

- ↑ McIntosh, Elise G. (August 15, 2009). "Bloomberg optimistic about North Shore rail". silive.com. Staten Island Advance. Retrieved July 31, 2015.

- ↑ Savino, Diane J. "Staten Island Railway Rider Report" (PDF). nysenate.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 17, 2014. Retrieved October 8, 2015.

- ↑ "MTA Capital Program Milestones Report" (PDF). mta.info. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. November 2010. Archived from the original on January 3, 2011. Retrieved September 12, 2016.

- ↑ "R34211 NOTICE -OF- ADDENDUM ADDENDUM #3" (PDF). mta.info. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. August 11, 2016. Retrieved August 15, 2016.

- ↑ "MTA Capital Program 2015–2019" (PDF). mta.info. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. October 28, 2015. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- ↑ "MTA Twenty-Year Capital Needs Assessment 2015-2034" (PDF). mta.info. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. October 2013. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- ↑ "R44 Maintenance Requirements". Flickr - Photo Sharing!. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. November 2013. Retrieved August 11, 2017.

- ↑ Raskin, Joseph B. (November 1, 2013), The Routes Not Taken: A Trip Through New York City's Unbuilt Subway System, Fordham University Press, ISBN 978-0-8232-5369-2

- ↑ Platt, Tevah (May 15, 2008). "A rail station for Rosebank?". silive.com. Archived from the original on 2008-10-08. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- ↑ Paulsen, Ken (July 12, 2018). "Reality check for Staten Island's rail plans". silive.com. Archived from the original on 2008-10-03. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- ↑ "Schumer Throws Support Behind S.I. Light Rail System". ny1.com. June 16, 2006. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- ↑ "NYCT North Shore Alternatives Analysis: Alternatives Analysis Report" (PDF). mta.info. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. August 2012. Retrieved July 20, 2015.

- ↑ "MTA Capital Program 2015-2019 Renew. Enhance. Expand.Amendment No. 2 As Proposed to the MTA Board May 2017" (PDF). mta.info. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. May 24, 2017. Retrieved May 24, 2017.

- ↑ "Staten Island's Rapid Transit: The New System Which Lessens Time and Increases Facilities" (PDF). The New York Times. March 9, 1886. Retrieved July 24, 2015.

- ↑ File:Staten Island Railway 1867.jpg. wikipedia.org.

- ↑ File:A Map of the Staten Island Rapid Transit Company from 1885.png. wikimedia.org.

- ↑ "Please use the first three cars to enter or exit the train at the following stations:". mta.info. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Retrieved August 14, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "New Arthur Kill Station" (Press release). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. January 20, 2017. Retrieved January 20, 2017.

- ↑ "Staten Island Rapid Transit 1921 – 1922 timetable". gretschviking.net. Staten Island Rapid Transit. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- 1 2 Drury, George H. (1994). The Historical Guide to North American Railroads: Histories, Figures, and Features of more than 160 Railroads Abandoned or Merged since 1930. Waukesha, Wisconsin: Kalmbach Publishing. pp. 312–314. ISBN 0-89024-072-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 "The Old Order Passeth: Rails Surrender To Roads: Passenger Runs on Two Lines of SIRT Will End at Midnight". Staten Island Advance. March 31, 1953. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- ↑ "STATEN ISLAND RAILROAD: CHEMICAL COAST LINE CONNECTOR" (PDF). American Association of Port Authorities. June 14, 2007. Retrieved December 16, 2014.

- 1 2 "MTA Board Approves Service Changes". mta.info. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. March 2010. Archived from the original on March 28, 2010. Retrieved August 14, 2017.

- ↑ Paulsen, Ken (July 12, 2008). "Reality check for Staten Island's rail plans". Staten Island Live. Archived from the original on 2008-10-03. Retrieved July 12, 2008.

- ↑ "Saint John's Avenue Embankment". railfanning.org. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- ↑ "Robin Road Trestle in 2018". gretschviking.net. 2018. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- ↑ "An aerial view of the filled in right of way and the new housing". gretschviking.net. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- ↑ "The abandoned ROW at the McClean Avenue bridge with the Major Avenue overpass in the distance". gretschviking.net. 1964. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- 1 2 Shore Front Drive, North Shore Section, Richmond, New York City: Environmental Impact Statement. 1973. pp. 25, 36, 53–54.

- ↑ Dominowski, Michael (December 7, 2008). "Permission to dream". silive.com. Retrieved October 8, 2015.

- ↑ Bommer, Edward (2003). Stations and Places Along the Staten Island Rapid Transit. Retrieved November 19, 2015.

- ↑ Ninth Annual Report December 31, 1929 (PDF). Port of New York Authority. 1929. p. 16.

- ↑ Pitanza, Marc (June 22, 2015). Staten Island Rapid Transit. Arcadia Publishing. p. 111. ISBN 9781439652039.

- ↑ Pitanza, Marc (January 28, 2007). "Ballasted Spur". nycsubway.org. Retrieved December 14, 2017.

- ↑ Pitanza, Marc (January 28, 2007). "Richmond Valley Spur". nycsubway.org. Retrieved December 14, 2017.

- ↑ Rosenfeld, Robbie (October 16, 2013). "Richmond Valley Spur". nycsubway.org. Retrieved December 14, 2017.

- 1 2 "236 Richmond Valley Road – Staten Island, New York Environmental Assessment Statement – Analyses" (PDF). Department of City Planning. August 29, 2014. Retrieved December 14, 2017.

- ↑ Pitanza, Marc (January 28, 2007). "Page Avenue Switch". nycsubway.org. Retrieved December 14, 2017.

- ↑ Kensinger, Nathan (June 23, 2016). "Exploring Staten Island's changing Mill Creek". Curbed NY. Retrieved December 14, 2017.

- ↑ Weinberg, Brian (July 12, 2007). "Tottenville express". nycsubway.org. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

External links

Route map:

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Staten Island Railway. |

- Official website

- MTA Subway Time – Staten Island Railway

- nycsubway.org - SIRT: Staten Island Rapid Transit

- SIRT artifacts in the Staten Island Historical Society Online Collections Database

- TrainsAreFun.com - Staten Island Rapid Transit

- Industrial & Offline Terminal Railroads of Brooklyn, Queens, Staten Island, Bronx & Manhattan - American Dock Company

- Industrial & Offline Terminal Railroads of Brooklyn, Queens, Staten Island, Bronx & Manhattan - Pouch Terminal

- Industrial & Offline Terminal Railroads of Brooklyn, Queens, Staten Island, Bronx & Manhattan - Procter & Gamble