New York Public Library

Coordinates: 40°45′10″N 73°58′54″W / 40.75270°N 73.98180°W

| |

|

| |

| Established | 1895 |

|---|---|

| Location | New York City |

| Branches | 92[1] |

| Collection | |

| Size | 53,000,000 books and other items[2] |

| Access and use | |

| Population served | 3,500,000 (Manhattan, The Bronx and Staten Island) |

| Other information | |

| Budget | US$302,208,000 (2017)[3] |

| Director |

Anthony Marx, President and CEO William P. Kelly, Andrew W. Mellon Director of the Research Libraries[4] |

| Staff | 3,150 |

| Website |

www |

The New York Public Library (NYPL) is a public library system in New York City. With nearly 53 million items and 92 locations, the New York Public Library is the second largest public library in the United States (behind the Library of Congress) and the third largest in the world.[5] It is a private, non-governmental, independently managed, nonprofit corporation operating with both private and public financing.[6] The library has branches in the boroughs of Manhattan, the Bronx, and Staten Island and affiliations with academic and professional libraries in the metropolitan area of New York State. The City of New York's other two boroughs, Brooklyn and Queens, are served by the Brooklyn Public Library and the Queens Library, respectively. The branch libraries are open to the general public and consist of circulating libraries. The New York Public Library also has four research libraries, which are also open to the general public.

The library, officially chartered as The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations, was developed in the 19th century, founded from an amalgamation of grass-roots libraries and social libraries of bibliophiles and the wealthy, aided by the philanthropy of the wealthiest Americans of their age.

The New York Public Library Main Branch building, which is easily recognizable by its lion statues named Patience and Fortitude that sit either side of the entrance, was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1965,[7] listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1966,[8] and designated a New York City Landmark in 1967.[9] It has also been featured in many television shows, including Seinfeld and Sex and the City, as well as films such as The Wiz in 1978, Ghostbusters in 1984, and The Day After Tomorrow in 2004.

History

Founding

At the behest of Joseph Cogswell, John Jacob Astor placed a codicil in his will to bequeath $400,000 (equivalent of $11.3 million in 2017) for the creation of a public library.[10] After Astor's death in 1848, the resulting board of trustees executed the will's conditions and constructed the Astor Library in 1854 in the East Village.[11] The library created was a free reference library; its books were not permitted to circulate.[12] By 1872, the Astor Library was described in a New York Times editorial as a "major reference and research resource",[13] but, "Popular it certainly is not, and, so greatly is it lacking in the essentials of a public library, that its stores might almost as well be under lock and key, for any access the masses of the people can get thereto".[14]

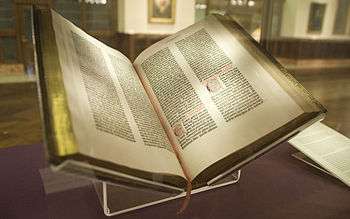

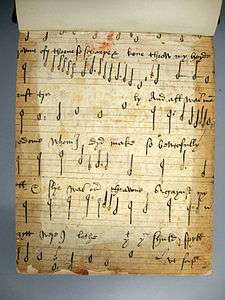

An act of the New York State Legislature incorporated the Lenox Library in 1870.[15][16] The library was built on Fifth Avenue, between 70th and 71th Streets, in 1877. Bibliophile and philanthropist James Lenox donated a vast collection of his Americana, art works, manuscripts, and rare books,[17] including the first Gutenberg Bible in the New World.[13] At its inception, the library charged admission and did not permit physical access to any literary items.[18]

Former Governor of New York and presidential candidate Samuel J. Tilden believed that a library with citywide reach was required, and upon his death in 1886, he bequeathed the bulk of his fortune—about $2.4 million (equivalent of $65 million in 2017)—to "establish and maintain a free library and reading room in the city of New York".[13] This money would sit untouched in a trust for several years, until John Bigelow, a New York attorney, and Andrew Haswell Green, both trustees of the Tilden fortune, came up with an idea to merge two of the city's largest libraries.[19]

Both the Astor and Lenox libraries were struggling financially. Although New York City already had numerous libraries in the 19th century, almost all of them were privately funded and many charged admission or usage fees. Bigelow, the most prominent supporter of the plan to merge the libraries found support in Lewis Cass Ledyard, a member of the Tilden Board, as well as John Cadwalader, on the Astor board. Eventually, John Stewart Kennedy, president of the Lenox board came to support the plan as well. On May 23, 1895, Bigelow, Cadwalader, and George L. Rives agreed to create "The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations".[19] The plan was hailed as an example of private philanthropy for the public good.[13] On December 11, John Shaw Billings was named as the library's first director.[19] The newly established library consolidated with the grass-roots New York Free Circulating Library in February 1901.[20]

In March, Andrew Carnegie tentatively agreed to donate $5.2 million (equivalent of $153 million in 2017) to construct sixty-five branch libraries in the city, with the requirement that they be operated and maintained by the City of New York.[21][22] The Brooklyn and Queens public library systems, which predated the consolidation of New York City, eschewed the grants offered to them and did not join the NYPL system; they believed that they would not get treatment equal to the Manhattan and the Bronx counterparts. Later in 1901, Carnegie formally signed a contract with the City of New York to transfer his donation to the city in order to enable it to justify purchasing the land for building the branch libraries.[23] The NYPL Board of trustees hired consultants for the planning, and accepted their recommendation that a limited number of architectural firms be hired to build the Carnegie libraries: this would ensure uniformity of appearance and minimize cost. The trustees hired McKim, Mead & White, Carrère and Hastings, and Walter Cook to design all the branch libraries.[24]

Collection development

The notable New York author Washington Irving was a close friend of Astor for decades and had helped the philanthropist design the Astor Library. Irving served as President of the library's Board of Trustees from 1848 until his death in 1859, shaping the library's collecting policies with his strong sensibility regarding European intellectual life.[25] Subsequently, the library hired nationally prominent experts to guide its collections policies; they reported directly to directors John Shaw Billings (who also developed the National Library of Medicine), Edwin H. Anderson, Harry M. Lydenberg, Franklin F. Hopper, Ralph A. Beals, and Edward Freehafer (1954–70).[26] They emphasized expertise, objectivity, and a very broad worldwide range of knowledge in acquiring, preserving, organizing, and making available to the general population nearly 12 million books and 26.5 million additional items.[27] The directors in turn reported to an elite board of trustees, chiefly elderly, well-educated, philanthropic, predominantly Protestant, upper-class white men with commanding positions in American society. They saw their role as protecting the library's autonomy from politicians as well as bestowing upon it status, resources, and prudent care.[28]

Representative of many major board decisions was the purchase in 1931 of the private library of Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich (1847–1909), uncle of the last tsar. This was one of the largest acquisitions of Russian books and photographic materials; at the time, the Soviet government had a policy of selling its cultural collections abroad for gold.[29]

The military drew extensively from the library's map and book collections in the world wars, including hiring its staff. For example, the Map Division's chief Walter Ristow was appointed as head of the geography section of the War Department's New York Office of Military Intelligence from 1942 to 1945. Ristow and his staff discovered, copied, and loaned thousands of strategic, rare or unique maps to war agencies in need of information not available through other sources.[30]

Research libraries

Main branch building

The organizers of the New York Public Library, wanting an imposing main branch, chose a central site available at the two-block section of Fifth Avenue between 40th and 42nd Streets. It was occupied by the defunct Croton Reservoir. Dr. John Shaw Billings, the first director of the library, created an initial design that became the basis of the new building (now known as the Schwarzman Building) on Fifth Avenue. Billings' plan called for a huge reading room on top of seven floors of book stacks, combined with a system that was designed to get books into the hands of library users as fast as possible.[13] Following a competition among the city's most prominent architects, Carrère and Hastings was selected to design and construct the building.[31] The cornerstone was laid in May 1902,[32] and the building's completion was expected to be in three years. In 1910, 75 miles (121 km) of shelves were installed, and it took a year to move and install the books that were in the Astor and Lenox libraries.[13]

On May 23, 1911, the main branch of the New York Public Library was officially opened in a ceremony presided over by President William Howard Taft. After a dedication ceremony, attended by 50,000 people, the library was open to the general public that day.[33] The library had cost $9 million to build, and its collection consisted of more than 1,000,000 volumes.[34] The library structure was a Beaux-Arts design and was the largest marble structure up to that time in the United States.[35] The two stone lions guarding the entrance were sculpted by E.C. Potter[36] and carved by the Piccirilli Brothers.[37] Its main reading room was contemporaneously the largest of its kind in the world at 77 ft (23 m) wide by 295 ft (90 m) long, with 50-foot-high (15 m) ceilings.[32] It is lined with thousands of reference books on open shelves along the floor level and along the balcony.

The building was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1965.[7] Over the decades, the library system added branch libraries, and the research collection expanded. By the 1970s, it was clear the collection eventually would outgrow the existing Fifth Avenue structure. In the 1980s, the central research library added more than 125,000 square feet (11,600 m2) of space and literally miles of bookshelf space to make room for future acquisitions. This expansion required a major construction project in which Bryant Park, directly west of the library, was closed to the public and excavated. The new library facilities were built below ground level and the park was restored above it.

In the three decades before 2007, the building's interior was gradually renovated.[35] On December 20, 2007, the library announced it would undertake a three-year, $50 million renovation of the building exterior, which has suffered damage from weathering and pollution.[38] The renovation was completed on time, and on February 2, 2011, the refurbished facade was unveiled.[39] The restoration design was overseen by Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates, Inc., whose previous projects include the Metropolitan Museum of Art's limestone facades and the American Museum of Natural History, made of granite.[40] These renovations were underwritten by a $100 million gift from philanthropist Stephen A. Schwarzman, whose name was to be inscribed at the bottom of the columns framing the building's entrances.[41] Today, the main reading room is equipped with computers with access to library collections and the Internet as well as docking facilities for laptops. A Fellows program makes reserved rooms available for writers and scholars, selected annually, and many have accomplished important research and writing at the library.[13]

Other research branches

In the 1990s, the New York Public Library decided to relocate that portion of the research collection devoted to science, technology, and business to a new location. The library purchased and adapted the former B. Altman department store on 34th Street. In 1995, the 100th anniversary of the founding of the library, the $100 million Science, Industry and Business Library (SIBL), designed by Gwathmey Siegel & Associates of Manhattan, opened to the public. Upon the creation of the SIBL, the central research library on 42nd Street was renamed the Humanities and Social Sciences Library.

Today there are four research libraries that comprise the NYPL's research library system; together they hold approximately 44,000,000 items. Total item holdings, including the collections of the Branch Libraries, are 50.6 million. The Humanities and Social Sciences Library on 42nd Street is still the heart of the NYPL's research library system. The SIBL, with approximately 2 million volumes and 60,000 periodicals, is the nation's largest public library devoted solely to science and business.[42] The NYPL's two other research libraries are the Schomburg Center for Research and Black Culture, located at 135th Street and Lenox Avenue in Harlem, and the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, located at Lincoln Center. In addition to their reference collections, the Library for the Performing Arts and the SIBL also have circulating components that are administered as ordinary branch libraries.

Recent history

The New York Public Library was not created by government statute. From its earliest days, the library was formed from a partnership of city government with private philanthropy.[13] As of 2010, the research libraries in the system are largely funded with private money, and the branch or circulating libraries are financed primarily with city government funds. Until 2009, the research and branch libraries operated almost entirely as separate systems, but that year various operations were merged. By early 2010, the NYPL staff had been reduced by about 16 percent, in part through the consolidations.[43]

In 2010, as part of the consolidation program, the NYPL moved various back-office operations to a new Library Services Center building in Long Island City. A former warehouse was renovated for this purpose for $50 million. In the basement, a new, $2.3 million book sorter uses bar codes on library items to sort them for delivery to 132 branch libraries. At two-thirds the length of a football field, the machine is the largest of its kind in the world, according to library officials. Books located in one branch and requested from another go through the sorter, which use has cut the previous waiting time by at least a day. Together with 14 library employees, the machine can sort 7,500 items an hour (or 125 a minute). On the first floor of the Library Services Center is an ordering and cataloging office; on the second, the digital imaging department (formerly at the Main Branch building) and the manuscripts and archives division, where the air is kept cooler; on the third, the Barbara Goldsmith Preservation Division, with a staff of 10 (as of 2010) but designed for as many as 30 employees.[43]

The NYPL maintains a force of NYC special patrolmen, who provide security and protection to various libraries, and NYPL special investigators, who oversee security operations at the library facilities. These officials have on-duty arrest authority granted by the New York Penal Law. Some library branches contract for security guards.

BookOps

In February 2013, the New York and Brooklyn public libraries announced that they would merge their technical services departments. The new department is called BookOps. The proposed merger anticipates a savings of $2 million for the Brooklyn Public Library and $1.5 million for the New York Public Library. Although not currently part of the merger, it is expected that the Queens Library will eventually share some resources with the other city libraries.[44][45] As of 2011, circulation in the New York Public Library systems and Brooklyn Public Library systems has increased by 59%. Located in Long Island City, BookOps was created as a way to save money while improving patrons service.[46] The services of BookOps include the Selection Team which "acquires, describes, prepares, and delivers new items for the circulating collections of Brooklyn Public Library (BPL) and New York Public Library, and for the general collections of NYPL's research libraries." Under the Selection Team are the Acquisitions Department, the Cataloging Department, The Collections Processing Unit, and the Logistics Department.[47] Before this facility opened, all the aforementioned departments were housed in different locations with no accountability between them, and items sometimes taking up to two weeks to reach their intended destination. BookOps now has all departments in one building and in 2015 sorted almost eight million items.[48] The building has numerous rooms, including a room dedicated to caring for damaged books.[49]

Controversies

The consolidations and changes in collections have promoted continuing debate and controversy since 2004 when David Ferriero was named the Andrew W. Mellon Director and Chief Executive of the Research Libraries.[50] NYPL had engaged consultants Booz Allen Hamilton to survey the institution, and Ferriero endorsed the survey's report as a big step "in the process of reinventing the library".[51] The consolidation program has resulted in the elimination of subjects such as the Asian and Middle East Division (formerly named Oriental Division), as well as the Slavic and Baltic Division.[52]

A number of innovations in recent years have been criticized. In 2004 NYPL announced participation in the Google Books Library Project. By agreement between Google and major international libraries, selected collections of public domain books would be scanned in their entirety and made available online for free to the public.[53] The negotiations between the two partners called for each to project guesses about ways that libraries are likely to expand in the future.[54] According to the terms of the agreement, the data cannot be crawled or harvested by any other search engine; no downloading or redistribution is allowed. The partners and a wider community of research libraries can share the content.[55]

The sale of the separately endowed former Donnell Library in midtown provoked controversy.[56] The elimination of Donnell was a result of the dissolution of children's, young adult and foreign language collections. The Donnell Media Center was also dismantled, the bulk of its collection relocated at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts as the Reserve Film and Video Collection, with parts of its collection redistributed.[57][58] The site was redeveloped for a luxury hotel.

Several veteran librarians have retired, and the number of age-level specialists in the boroughs have been cut back.[59]

Branch libraries

The New York Public Library system maintains commitment as a public lending library through its branch libraries in The Bronx, Manhattan and Staten Island, including the Mid-Manhattan Library, the Andrew Heiskell Braille and Talking Book Library, the circulating collections of the Science, Industry and Business Library, and the circulating collections of the Library for the Performing Arts. The branch libraries comprise the third-largest library in the United States.[60] These circulating libraries offer a wide range of collections, programs, and services, including the renowned Picture Collection at Mid-Manhattan Library and the Media Center, redistributed from Donnell.

The system has 39 libraries in Manhattan, 35 in the Bronx, and 13 in Staten Island. The newest is the 53rd Street Branch Library, located in Manhattan, which opened on June 26, 2016.[61]

As of 2016, the New York Public Library consisted of four research centers and 88 neighborhood branch libraries in the three boroughs served.[62] All libraries in the NYPL system may be used free of charge by all visitors. As of 2010, the research collections contain 44,507,623 items (books, videotapes, maps, etc.). The Branch Libraries contain 8,438,775 items.[63] Together the collections total nearly 53 million items, a number surpassed only by the Library of Congress and the British Library.

Taken as a whole, the three library systems in the city have 209 branches with 63 million items in their collections.

Services

ASK NYPL

Telephone Reference, known as ASK NYPL,[64] answers 100,000 questions per year, by phone and online,[65] as well as in The New York Times.[66][67]

Website and digital holdings

The Library website provides access to the library's catalogs, online collections and subscription databases. It also has information about the library's free events, exhibitions, computer classes and English as a Second Language (ESL) classes.[68] The two online catalogs, LEO[69] (which searches the circulating collections) and CATNYP (which searches the research collections) allow users to search the library's holdings of books, journals and other materials. The LEO system allows cardholders to request books from any branch and have them delivered to any branch.

The NYPL gives cardholders free access from home to thousands of current and historical magazines, newspapers, journals and reference books in subscription databases, including EBSCOhost, which contains full text of major magazines; full text of the New York Times (1995–present), Gale's Ready Reference Shelf which includes the Encyclopedia of Associations and periodical indexes, Books in Print;[70] and Ulrich's Periodicals Directory. The New York Public Library also links to outside resources, such as the Bureau of Labor Statistics' Occupational Outlook Handbook, and the CIA's World Factbook. Databases are available for children, teenagers, and adults of all ages.[71]

The NYPL Digital Collections (formerly named Digital Gallery)[72] is a database of over 700,000 images digitized from the library's collections. The Digital Collections was named one of Time Magazine's 50 Coolest Websites of 2005[73] and Best Research Site of 2006[74] by an international panel of museum professionals.

The Photographers' Identities Catalog (PIC) is an experimental online service of the Photography Collection in the Stephen A. Schwarzman Building.[75]

Other databases available only from within the library include Nature, IEEE and Wiley science journals, Wall Street Journal archives, and Factiva. Overall, the digital holdings for the Library consist of more than a petabyte of data as of 2015.[76]

One NYPL

In 2006, the library adopted a new strategy that merged branch and research libraries into "One NYPL". The organizational change developed a unified online catalog for all the collections, and one card to that could be used at both branch and research libraries.[57] The 2009 website and online-catalog transition had some initial difficulties, but ultimately the catalogues were integrated.[77]

Community outreach

The New York Public Library offers many services to its patrons. Some of these services include services for immigrants. New York City is known for having a welcoming environment when its comes to people of diverse backgrounds. The library offers free work and life skills classes. These are offered in conjunction with volunteers and partnerships at the library. In addition, the library offers non-English speakers materials and coaching for them to acclimate to the U.S. For these non-English speakers, the library offers free ESOL classes. An initiative was taken in July 2018, NYC library card holders are allowed to visit Whitney Museum, the Guggenheim and 31 other prominent New York cultural institutions for free.[78]

Governance

The NYPL, like all public libraries in New York, is granted a charter from the Board of Regents of the University of the State of New York and is registered with the New York State Education Department.[79] The basic powers and duties of all library boards of trustees are defined in the Education Law and are subject to Part 90 of Title 8 of the New York Codes, Rules and Regulations.[79]

The NYPL's charter, as restated and granted in 1975, gives the name of the corporation as The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations. The library is governed by a board of trustees, composed of between 25–42 trustees of several classes who collectively choose their own successors, including ex officio the New York City Mayor, New York City Council Speaker and New York City Comptroller.[80]

In popular culture

The historian David McCullough has described the New York Public Library as one of the five most important libraries in the United States; the others are the Library of Congress, the Boston Public Library, and the university libraries of Harvard and Yale.[81]

The New York Public Library has been referenced numerous times in popular culture. The library has appeared as a setting and topic multiple times in film, poetry, music, television, and music.

Other New York City library systems

The New York Public Library, serving Manhattan, the Bronx, and Staten Island, is one of three separate and independent public library systems in New York City. The other two library systems are the Brooklyn Public Library and the Queens Library.

According to the 2006 Mayor's Management Report, New York City's three public library systems had a total library circulation of 35 million: the NYPL and BPL (with 143 branches combined) had a circulation of 15 million, and the Queens system had a circulation of 20 million through its 62 branch libraries. Altogether the three library systems hosted 37 million visitors in 2006.

Other libraries in New York City, some of which can be used by the public, are listed in the Directory of Special Libraries and Information Centers.[82]

In June 2017 Subway Library was announced.[83] It was an initiative between The New York Public Library, Brooklyn Public Library, and Queens Library, the MTA, and Transit Wireless. The Subway Library gave riders access to e-books, excerpts, and short stories. Subway Library has since ended, but riders can still download free e-books via the SimplyE app or by visiting SimplyE.net.

See also

- Education in New York City

- Google Books Library Project

- List of museums and cultural institutions in New York City

- Benjamin Miller Collection NYPL Collection of Postage Stamps

- Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs

- The New York Public Library Desk Reference

- List of New York Public Library Branches

References

- ↑ About The New York Public Library

- ↑ "New York Public Library General Fact Sheet" (PDF). Nypl.org. Retrieved 2012-11-24.

- ↑ "New York Public Library Annual Report 2017" (PDF). Nypl.org. Retrieved 2018-09-19.

- ↑ "President and Leadership". Nypl.org. Retrieved 2016-12-29.

- ↑ Burke, Pat (July 2, 2015). "CTO Takes the New York Public Library Digital". CIO Insight. Quinstreet Enterprise. Retrieved 2015-07-12.

- ↑ The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations. Financial Statements and Supplemental Schedules, June 2016, page 8.

- 1 2 "New York Public Library". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. September 16, 2007. Archived from the original on December 5, 2007.

- ↑ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. January 23, 2007. Archived from the original on October 2, 2007.

- ↑ "New York Public Library" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. January 11, 1967. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ↑ Lydenberg 1916a, pp. 556–563

- ↑ Lydenberg 1916a, pp. 563–573

- ↑ Lydenberg 1916a, pp. 573–574

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "History of the New York Public Library". nypl.org. Retrieved June 12, 2011.

- ↑ "Editorial: Free Public Libraries". The New York Times. January 14, 1872. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ↑ An Act to Incorporate the Trustees of the Lenox Library (L. 1870, ch. 2; L. 1892, ch. 166)

- ↑ Lydenberg 1916b, p. 688; A Superb Gift

- ↑ Lydenberg 1916b, pp. 685–689

- ↑ Lydenberg 1916b, pp. 690, 694–695

- 1 2 3 Reed 2011, pp. 1–10

- ↑ "Lent Eleven Million Books". New-York Tribune. April 14, 1901. p. 16.

- ↑ "CITY WILL ACCEPT MR. CARNEGIE'S LIBRARIES; Formal Action by the Board of Estimate to Be Taken To-morrow". The New York Times. 1901-03-17. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-07-25.

- ↑ "Carnegie Offers City Big Gift". New-York Tribune. March 16, 1901. pp. 1–2.

- ↑ "Library Plans All Right Now: Carnegie Approves Controller Coler Contracts". The Evening World. September 9, 1901. p. 3. ; Carnegie Approves the Contracts, Mr. Carnegie's Libraries (New York Times September 10, 1901)

- ↑ Van Slyck (1995), pp. 113–114

- ↑ Myers, Andrew (1968). "Washington Irving and the Astor Library". Bulletin of the New York Public Library. 72 (6): 378–399.

- ↑ Chapman, Gilbert W. (1970). "Edward G. Freehafer: An Appreciation". Bulletin of the New York Public Library. 74 (10): 625–628.

- ↑ Dain, Phyllis (1995). "'A Coral Island': A Century of Collection Development in the Research Libraries of the New York Public Library". Biblion. 3 (2): 5–75.

- ↑ Dain, Phyllis (March 1991). "Public Library Governance and a Changing New York City". Libraries & Culture. 26 (2): 219–250.

- ↑ Kasinec, Edward; Davis, Jr., Robert H. (1990). "Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich (1847–1909) and His Library". Journal of the History of Collections. 2 (2): 135–142.

- ↑ Hudson, Alice C. (1995). "The Library's Map Division Goes to War, 1941–45". Biblion. 3 (2): 126–147.

- ↑ "Public Library Plans". New-York Tribune. December 5, 1897. p. 13. ; 'Winners of the Prize'

- 1 2 "The New York Public Library". The Sun. April 9, 1911. p. 9.

- ↑ "50,000 People at the Dedication of the City's Great Library; Taft and Dix Take Part". The Evening World. May 23, 1911. p. 1. ; New Public Library Formally Dedicated

- ↑ "Our New Library Dedicated". The New York Sun. May 24, 1911. p. 5.

- 1 2 Pogrebin, Robin (December 20, 2007). "A Centennial Face-Lift for a Beaux-Arts Gem". New York Times. Archived from the original on January 8, 2012. Retrieved January 6, 2012.

- ↑ "Sculptor Potter Hurt". The Evening World. November 2, 1911. p. 9. ; cf. Cupid Turns Him from Study of Theology to Art, The Library Lions

- ↑ Potter, Edward Clark (1910). Lions. Carrere & Hastings, Piccirilli Brothers Marble Carving Studios.

- ↑ "The New York Public Library Will Restore its Fifth Avenue Building's Historic Facade / Project to be Completed in Time for Building's 2011 Centennial", 2007-12-20, New York Public Library Web site, accessed December 20, 2007.

- ↑ "New York Public Library gets a 50M facelift for 100th birthday" Archived February 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine., New York Daily News, 2011-02-02, accessed February 5, 2011.

- ↑ Pogrebin, Robin (20 December 2007). "A Centennial Face-Lift for a Beaux-Arts Gem". New York Times. Retrieved March 30, 2009.

- ↑ Santora, Marc (April 23, 2008). "After Big Gift, a New Name for the Library". New York Times.

- ↑ "Science, Industry and Business Library", June 19, 2003 Press Release, New York Public Library. Retrieved June 13, 2010.

- 1 2 Taylor, Kate, "That Mighty Sorting Machine Is Certainly One for the Books", New York Times, April 21, 2010, retrieved same day

- ↑ Meredith Schwartz, "NYPL, Brooklyn Merge Technical Services", Library Journal, February 22, 2013

- ↑ "BookOps". Retrieved 2015-09-20.

- ↑ "BookOps - Shared Technical Services between BPL & NYPL | Urban Libraries Council". www.urbanlibraries.org. Retrieved 2017-09-25.

- ↑ "SERVICES - BookOps.org". sites.google.com. Retrieved 2017-09-25.

- ↑ "Behind the Scenes at BookOps, the New York Public Library's Laser Sorting Facility". Viewing NYC. 2016-02-03. Retrieved 2017-09-25.

- ↑ "Keepers of the Secrets | Village Voice". Retrieved 2017-09-25.

- ↑ Norman Oder, "One NYPL," Many Questions, Library Journal, November 1, 2007 Archived July 4, 2008, at the Wayback Machine..

- ↑ Oder, Norman. "NYPL Reorganization Coming", Library Journal (October 1, 2007). Vol. 132, Issue 16, p. 12.

- ↑ Sherman, Scott (December 19, 2011). "Upheaval at the New York Public Library". The Nation.

- ↑ New York Public Library + Google

- ↑ Rothstein, Edward. "If Books Are on Google, Who Gains and Who Loses?" New York Times. November 14, 2005.

- ↑ "LITA PreConference: Contracting for Content in a Digital World". LITA Blog.

- ↑ Chan, Sewell. "Sale of Former Donnell Library Is Back on Track", New York Times. July 9, 2009.

- 1 2 LeClerc, Paul. "Answers About the New York Public Library, Part 3", New York Times. December 12, 2008.

- ↑ "Reserve Film and Video Collection," New York Public Library website (accessed 2 February 2016).

- ↑ "NYPL head = Natl. archivist; New Catalog, Restructuring". Library Journal. 134 (13). August 1, 2009.

- ↑ "American Library Association: The Nation's Largest Libraries". Ala.org. Archived from the original on April 13, 2009. Retrieved March 17, 2009.

- ↑ "About the 53rd Street Library". NYPL. Jan. 2, 2017.

- ↑ "NYPL Facts at a Glance" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on November 7, 2016. Retrieved November 7, 2016.

- ↑ "2010 Annual Report" (PDF). Annualreports.nypl.org. Retrieved 2012-11-24.

- ↑ The New York Public Library. "Get Help / Ask NYPL | The New York Public Library". Nypl.org. Retrieved 2012-11-24.

- ↑ "Before Google Search There Was the Library". Retrieved 2015-04-08.

- ↑ Study, C. "At Your Service: Information Sleuth at the New York Public Library". Retrieved 2015-04-07.

- ↑ "Library Phone Answerers Survive the Internet". The New York Times. June 19, 2006.

- ↑ The New York Public Library. "Welcome to The New York Public Library". Nypl.org. Retrieved 2012-11-24.

- ↑ "New York Public Library Catalog". Leopac.nypl.org. Retrieved 2012-11-24.

- ↑ The New York Public Library (2012-11-13). "Articles and Databases | The New York Public Library". Nypl.org. Retrieved 2012-11-24.

- ↑ The New York Public Library (2012-11-13). "Articles and Databases | The New York Public Library". Nypl.org. Retrieved 2016-05-05.

- ↑ "NYPL Digital Gallery | Home". Digitalgallery.nypl.org. Retrieved 2012-11-24.

- ↑ Archived July 21, 2006, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Best of the Web: Categories: Research (Best Research Site)". Archimuse.com. Retrieved 2012-11-24.

- ↑ David Lowe (2016). "Photographers' Identities Catalog". The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs. Retrieved 2018-01-11.

- ↑ Archived February 8, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Slotnik, Daniel E. "Library System Resolves Catalog Problems", New York Times. July 20, 2009.

- ↑ "A Library Card Will Get You Into the Guggenheim (and 32 Other Places)". Retrieved 2018-07-17.

- 1 2 Nichols, Jerry, Handbook for Library Trustees of New York State (2015 ed.), New York State Library

- ↑ Woodrum, Pat (1989). Managing Public Libraries in the 21st Century. pp. 84–85. ISBN 0-86656-945-6. LCCN 89-20016.

- ↑ "Simon & Schuster:David McCullough". Archived from the original on September 29, 2006. Retrieved October 12, 2007.

- ↑ The New York Public Library (2012-11-13). "Directory of Special Libraries and Information Centers | The New York Public Library". Nypl.org. Retrieved 2012-11-24.

- ↑ "Announcing #SubwayLibrary: Free E-Books for Your Commute". The New York Public Library. Retrieved 2018-03-19.

Bibliography

- Chapman, Carleton B. Order out of Chaos: John Shaw Billings and America's Coming of Age (1994)

- Dain, Phyllis. The New York Public Library: A History of Its Founding and Early Years (1973)

- Davis, Donald G. Jr and Tucker, John Mark (1989). American Library History: a comprehensive guide to the literature. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, Inc. ISBN 0-87436-142-7

- Glynn, Tom, Reading Publics: New York City's Public Libraries, 1754-1911 (Fordham University Press, 2015). xii, 447 pp.

- Harris, Michael H. and Davis, Donald G. Jr. (1978). American Library History: a bibliography. Austin: University of Texas ISBN 0-292-70332-5

- Lydenberg, Harry Miller (1916a). "History of the New York Public Library: Part I". Bulletin of the New York Public Library. 20: 555–619.

- Lydenberg, Harry Miller (1916b). "History of the New York Public Library: Part III". Bulletin of the New York Public Library. 20: 685–734.

- Lydenburg, Harry Miller (1923). History of the New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations. The New York Public Library.

- Myers, Andrew B. The Worlds of Washington Irving: 1783–1859 (1974)

- Reed, Henry Hope. The New York Public Library: Its Architecture and Decoration (1986)

- Reed, Henry Hope (2011). The New York Public Library: The Architecture and Decoration of the Stephen A. Schwarzman Building. 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY: W.W. Norton and Company. ISBN 978-0-393-07810-7.

- Sherman, Scott (2015). Patience and fortitude : power, real estate, and the fight to save a public library, Brooklyn ; London : Melville House, ISBN 978-1-61219-429-5

- Van Slyck, Abigail A. (1995). Free to All: Carnegie Libraries & American Culture, 1890–1920. Chicago: IL: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-85031-5.

Further reading

- Rabina, Debbie; Peet, Lisa (2014). "Meeting a Composite of User Needs Amidst Change and Controversy: The Case of the New York Public Library". Reference & User Services Quarterly. 54 (2): 52–59. ISSN 1094-9054. JSTOR refuseserq.54.2.52.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to New York Public Library. |