Columbus County, North Carolina

| Columbus County, North Carolina | |

|---|---|

Columbus County Courthouse, Whiteville | |

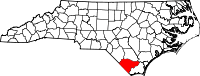

Location in the U.S. state of North Carolina | |

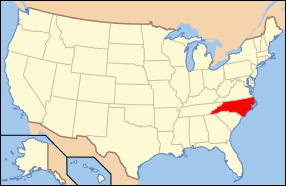

North Carolina's location in the U.S. | |

| Founded | 1808 |

| Named for | Christopher Columbus |

| Seat | Whiteville |

| Largest city | Whiteville |

| Area | |

| • Total | 954 sq mi (2,471 km2) |

| • Land | 937 sq mi (2,427 km2) |

| • Water | 16 sq mi (41 km2), 1.7% |

| Population | |

| • (2010) | 58,098 |

| • Density | 160/sq mi (62/km2) |

| Congressional district | 7th |

| Time zone | Eastern: UTC−5/−4 |

| Website |

www |

Columbus County is a county located in the U.S. state of North Carolina. As of the 2010 census, the population was 58,098.[1] Its county seat is Whiteville.[2]

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 954 square miles (2,470 km2), of which 937 square miles (2,430 km2) is land and 16 square miles (41 km2) (1.7%) is water.[3] It is the third-largest county in North Carolina by land area. There are several large lakes within the county, including Lake Tabor and Lake Waccamaw.

One of the most significant geographic features is the Green Swamp, a 15,907-acre area along highway 211 in the north-eastern portion of the county. It contains several unique and endangered species, such as the venus flytrap. The area contains the Brown Marsh Swamp, and has a remnant of the giant longleaf pine forest that once stretched across the Southeast from Virginia to Texas.[4]

Major highways

History

The county was formed in 1808 in the early federal period from parts of Bladen and Brunswick counties. It was named for Christopher Columbus.[5]

Waccamaw Siouan Indian tribe

The Waccamaw Siouan Indians are one of eight state-recognized tribes. Their homeland territory is at the edge of Green Swamp in present-day Columbus County. Historically, the "eastern Siouans" had territories extending through the area of Columbus County prior to any European exploration or settlement in the 16th century.

English colonial settlement in what was known as Carolina did not increase until the late 17th and early 18th centuries. Following epidemics of infectious disease, the indigenous peoples also suffered disruption and fatalities during the colonial Tuscarora and Yamasee wars. Afterward most of the Tuscarora people migrated north, joining other Iroquoian-speaking peoples of the Iroquois Confederacy in New York State by 1722, when they declared their migration ended and official tribe relocated to that area.

The Waccamaw Siouan ancestors retreated for safety to an area of Green Swamp near Lake Waccamaw.[6] Throughout the 19th century, the Waccamaw Siouan were seldom mentioned in the historical record. Toward the end of the century, the U.S. Census recorded common Waccamaw surnames among individuals in the small isolated communities of this area.[7]

In 1910, the earliest-known governmental body of the Waccamaw Indians was officially created, named the Council of Wide Awake Indians. At a time of racial segregation in North Carolina schools, the council sought to gain public funding for Indian schools, as the Lumbee (then known as Croatan Indians) had achieved in the late 19th century. They also hoped to gain federal recognition as a tribe, but it was rare for landless Indians and was associated with the tribes that had official treaties with the United States, typically those on reservations. The Council opened its first publicly funded school in 1933, founding others soon after. They continued to have difficulty in getting state funding for schools, as minorities had been disenfranchised in North Carolina since passage of a suffrage amendment in 1900 that created barriers to voter registration. The Council campaigned for federal recognition in 1940 during the President Franklin D. Roosevelt administration, which had passed the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, encouraging tribes to re-establish self-government.[7]

The name Waccamaw Siouan was first officially used in US government documents in 1949, when a bill intended to grant the tribe federal recognition was introduced in Congress by the representative of this district.[7] The bill was defeated in committee the following year. But changes in federal policy following Native American activism in the 1960s and 1970s enabled the Waccamaw Indians to obtain more public funding and economic assistance even without federal recognition.[7]

The Waccamaw Siouan have been recognized by the North Carolina Commission of Indian Affairs since 1971, as one of eight state-recognized tribes. The tribe organized as the Waccamaw Siouan Development Association (WSDA), a nonprofit group founded in 1972. The group is headed by a nine-member board of directors, elected by secret ballot in elections open to all enrolled tribal members over the age of 18; in addition, the board includes a chief, whose role is largely symbolic.[7]

COLCOR

From January 1979 through December 1982 [8], State and Federal Investigators conducted Operation NC Gateway, an investigation into the activities of several elected officials in Brunswick and Columbus counties. Law enforcement seized 37 million dollars of illegal drugs, and arrested several leading citizens in the area. The scandal was labeled "COLCOR" in the press, shorthand for Columbus Corruption.[9] The federal investigation culminated in federal convictions of former sheriff Herman Strong and former Shallotte Police Chief Hoyal Varnum Jr. among other government officials.[10] The 1983 street value of the narcotics in Strong and his co-conspirators’ criminal enterprise was $180 million.[11]

COLCOR's success was largely due to the deep undercover work by FBI Special Agent Robert Drdak who's testimony to the Grand Jury led to the arrest of a long list of prominent Brunswick and Columbus County citizens. In addition, former U.S. Attorney, Samuel Currin, was the force behind operations ColCor and Operation Gateway. The special investigative grand jury in Brunswick County handed down 22 indictments . [11], and 35 indictments in Columbus County. [8] Among those indicted were [8], [12] [13] :

- Brunswick County Sheriff Herman Strong (numerous charges of conspiring to smuggle drugs, providing protection to drug smugglers, accepting bribes and 2 incidents of drug smuggling marijuana and methaqualone tablets) Strong was released June 17, 1987, after serving less than four years [11]

- Shallotte Police Chief Hoyal "Red" Varnum (conspiring to possess with intent to distribute 1,100 to 1,400 pounds of marijuana)

- Hoyal's brother Steve Varnum (a past Chairman of the Brunswick County Commissioners),

- Lake Waccamaw Police Chief L. Harold Lowery, (racketeering in connection with taking $1,650 in bribes for protection money)

- Former Columbus County Commissioner Edward Walton Williamson (who gave the undercover agent money to deal with Star News reporter Judith Tillman and send her back to Alabama)[14]

- District Court Judge J. Wilton Hunt (racketeering and interstate gambling) A federal judge sentenced Hunt to 14 years in prison and a $10,000 for his role in the corruption ring.[11]

- State Rep. G. Ronald Taylor, (burning three warehouses belonging to another state senator who was Taylor's competition in the farm-implement business)

- Lt. Governor James C. Green (charged with taking a $2,000 bribe and conspiring to take $10,000 in bribes a month) [12] [13] The jury found insufficient evidence for the charges and acquitted Green. [15]

- NC State Senator R C Soles was indicted on federal charges of aiding and abetting a former Columbus County commissioner in obtaining bribes from undercover FBI agents, conspiracy, vote-buying and perjury, but these charges were later dismissed. [16]

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1810 | 3,022 | — | |

| 1820 | 3,912 | 29.5% | |

| 1830 | 4,141 | 5.9% | |

| 1840 | 3,941 | −4.8% | |

| 1850 | 5,909 | 49.9% | |

| 1860 | 8,597 | 45.5% | |

| 1870 | 8,474 | −1.4% | |

| 1880 | 14,439 | 70.4% | |

| 1890 | 17,856 | 23.7% | |

| 1900 | 21,274 | 19.1% | |

| 1910 | 28,020 | 31.7% | |

| 1920 | 30,124 | 7.5% | |

| 1930 | 37,720 | 25.2% | |

| 1940 | 45,663 | 21.1% | |

| 1950 | 50,621 | 10.9% | |

| 1960 | 48,973 | −3.3% | |

| 1970 | 46,937 | −4.2% | |

| 1980 | 51,037 | 8.7% | |

| 1990 | 49,587 | −2.8% | |

| 2000 | 54,749 | 10.4% | |

| 2010 | 58,098 | 6.1% | |

| Est. 2016 | 56,505 | [17] | −2.7% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[18] 1790-1960[19] 1900-1990[20] 1990-2000[21] 2010-2013[1] | |||

As of the census[22] of 2000, there were 54,749 people, 21,308 households, and 15,043 families residing in the county. The population density was 58/sq mi (23/km²). As of 2004, there were 24,668 housing units at an average density of 26/sq mi (10/km²). The racial makeup for the county was 68.9% White, 23.1% Black or African American, 5.1% Native American, 0.2% Asian, 4.7% from other races, and 0.6% from two or more races. 2.7% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

By 2005 62.3% of the county population was White. 31.1% of the population was African-American. 3.2% of the population was Native American. According to the 2010 census, 1,025 people in Columbus County self-identify as Waccamaw Siouan.[23] 2.8% of the population was Latino.

There were 21,308 households out of which 31.50% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 50.80% were married couples living together, 15.80% had a female householder with no husband present, and 29.40% were non-families. 26.50% of all households were made up of individuals and 11.70% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.50 and the average family size was 3.01.

In the county, the population was spread out with 25.70% under the age of 18, 8.70% from 18 to 24, 27.40% from 25 to 44, 24.40% from 45 to 64, and 13.80% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 37 years. For every 100 females there were 92.60 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 89.40 males.

The 2003 median income for a household in the county was $27,659, and the median income for a family was a little more than $33,800. Males had a median income of $28,494 versus $19,867 for females. The per capita income for the county was $14,415. About 17.60% of families and 20.30% of the population were below the poverty line, including 30.00% of those under age 18 and 25.50% of those age 65 or over.

Economics

The economy of Columbus County centers on two different industries: agriculture and manufacturing. Columbus farmers produce crops such as pecans and peanuts along with soybeans, potatoes, and corn. Cattle, poultry, and catfish are other agricultural products in Columbus County. Factories in the region focus on textiles, tools, and plywood. Household products such as doors, furniture, and windows are other manufactured goods produced in Columbus.[24]

Carolina Southern stopped railroad service to the county in 2012, and efforts to restore service have proven difficult.[25] However, as of July 2014, positive developments were reported to return railroad service to the area, a move considered necessary for spurring economic development in the area.[26] Carolina Southern agreed, in July 2014, to begin the process allowing the counties of Horry County, South Carolina, Marion, South Carolina and Columbus County, NC to assume control of the area rail lines with the hopes repairing the railroad tracks and bridges and then finding a buyer to re-establish service to the area.[27] A public hearing on the matter was held on October 6, 2014.[28] During the October 6th meeting, the Columbus County Commissioners voted to support the initiative to restart rail service with a 10-year grant for the program. Some of the commissioners may not have revealed that they will benefit from the re-establishment of rail service.[29] The Horry County Council, in a vote on October 7, 2014 also voted to provide funding to reestablish railroad service to the area.[30] Although originally it was thought service could be restored as early as spring 2015,[31] however, the sale of the railroad was not completed until August, 2015 to R.J. Coleman Railroad..[32] A new target date of February 2016 was announced, as millions of dollars are expected to be spent repairing the rail lines that have been idle since 2011.[33]

Law and government

Columbus County is a member of the regional Cape Fear Council of Governments. The county is governed by a board of seven Commissioners.

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 60.1% 14,272 | 38.2% 9,063 | 1.7% 397 |

| 2012 | 53.4% 12,941 | 45.6% 11,050 | 1.0% 252 |

| 2008 | 53.5% 12,994 | 45.6% 11,076 | 0.9% 212 |

| 2004 | 50.8% 10,773 | 48.8% 10,343 | 0.4% 75 |

| 2000 | 45.3% 8,342 | 54.2% 9,986 | 0.5% 97 |

| 1996 | 37.0% 6,017 | 55.4% 9,019 | 7.6% 1,244 |

| 1992 | 28.9% 5,462 | 60.6% 11,469 | 10.5% 1,985 |

| 1988 | 41.9% 6,659 | 57.8% 9,172 | 0.3% 51 |

| 1984 | 51.1% 9,150 | 48.8% 8,728 | 0.2% 26 |

| 1980 | 34.6% 5,522 | 64.1% 10,212 | 1.3% 206 |

| 1976 | 22.1% 3,184 | 77.4% 11,148 | 0.5% 69 |

| 1972 | 70.6% 8,468 | 27.6% 3,305 | 1.8% 214 |

| 1968 | 26.2% 3,881 | 28.6% 4,243 | 45.2% 6,693 |

| 1964 | 33.2% 4,471 | 66.8% 9,004 | |

| 1960 | 25.9% 3,655 | 74.1% 10,455 | |

| 1956 | 22.8% 2,300 | 77.2% 7,805 | |

| 1952 | 30.2% 3,001 | 69.8% 6,941 | |

| 1948 | 15.0% 1,105 | 74.8% 5,511 | 10.2% 753 |

| 1944 | 21.4% 1,552 | 78.7% 5,717 | |

| 1940 | 13.7% 934 | 86.3% 5,900 | |

| 1936 | 16.0% 1,214 | 84.0% 6,359 | |

| 1932 | 12.6% 739 | 86.6% 5,098 | 0.9% 53 |

| 1928 | 55.3% 3,533 | 44.7% 2,854 | |

| 1924 | 36.9% 1,629 | 62.5% 2,757 | 0.6% 26 |

| 1920 | 36.4% 1,783 | 63.6% 3,111 | |

| 1916 | 38.2% 1,327 | 61.7% 2,143 | 0.1% 2 |

| 1912 | 5.7% 155 | 61.4% 1,668 | 32.9% 892 |

Columbus County Animal Shelter

Columbus County maintains an animal shelter at 288 Legion Drive in Whiteville, NC. It has been a target both from government regulators as well as activist [35] with problems present for "years and years and years" [36] In the past, the shelter has been fined [37] as well as receiving warning from state regulators for various issues.[38]

In September 2015, a new manager was hired to combat these issues,[39] and he announced an ambitious plan to improve the shelter. In late October 2015, WECT ran a story showing that things at the shelter were indeed improving, highlighting a large donation from Austria that was made possible by coordination on Facebook. The story also enumerated more changes that the new director has made to improve conditions.[35] As of November 2015, the volunteers maintain a Facebook page showing the animals the shelter has available for adoption.[40]

Libraries

The county maintains a system of 6 libraries. The first public library for the county opened in 1921.[41]

Prisons

There are two state prisons in the county, one at Tabor City, the Tabor City Correctional Institution, and one at Brunswick,[42]

Sheriff Department

The Sheriff's office provides law enforcement services for the county as well as operating the Columbus County Detention Center. As of January 2016, the current sheriff is Lewis Hatcher.[43]

Communities

Cities

- Tabor City

- Whiteville (named county seat in 1832 [38])

Towns

Townships

- Bogue

- Bolton

- Bug Hill

- Cerro Gordo

- Chadbourn

- Fair Bluff

- Lees

- Ransom

- South Williams

- Tatums

- Waccamaw

- Welch Creek

- Western Prong

- Williams

- Whiteville

Census-designated places

Unincorporated areas

See also

References

- 1 2 "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 18, 2013.

- ↑ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on 2011-05-31. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- ↑ "2010 Census Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. August 22, 2012. Archived from the original on January 12, 2015. Retrieved January 13, 2015.

- ↑ "The Green Swamp", My Reporter, April 2009

- ↑ Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. Govt. Print. Off. p. 88.

- ↑ William S. Powell, Encyclopedia of North Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), 1170.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Powell, Encyclopedia of North Carolina, 1170.

- 1 2 3

- ↑ "COLCOR REDUX". crime.blogs.com. Retrieved 2017-07-26.

- ↑ "Operation N.C. Gateway stings Brunswick's former sheriff in early 80s". brunswickbeacon.com. Retrieved 2017-07-26.

- 1 2 3 4 "Under investigation: A tale of three decades - BrunswickBeacon.com". www.brunswickbeacon.com. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- 1 2 "COLCOR REDUX". CRIME REPORT. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- 1 2 AP. "GRAND JURY INDICTS LIEUT. GOV. GREEN OF NORTH CAROLINA". Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ↑ Then, Scott Nunn Back. "1982: FBI arrests Waccamaw police chief, 20 others". Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ↑ "Political Grudges Are Nothing New". Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ↑ "Timeline of R.C. Soles' career". Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ↑ "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved June 9, 2017.

- ↑ "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on April 22, 2013. Retrieved January 13, 2015.

- ↑ "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved January 13, 2015.

- ↑ Forstall, Richard L., ed. (March 27, 1995). "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 13, 2015.

- ↑ "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. April 2, 2001. Retrieved January 13, 2015.

- ↑ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2013-09-11. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ Commission on Indian Affairs, North Carolina Department of Administration. (2010). "Total Population by Tribe by County in North Carolina." "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-04-02. Retrieved 2015-04-01.

- ↑ http://mangowebdesign.com, Website design and web development by Mango Web Design. "Columbus County (1808) - North Carolina History Project". North Carolina History Project. Retrieved 2018-03-15.

- ↑ Jones, Steve. "STB filing: Railroad revenue not important in reaching a decision | Business". MyrtleBeachOnline.com. Archived from the original on 2014-04-16. Retrieved 2014-04-22.

- ↑ "Tabor-Loris Tribune – July 16, 2014". tabor-loris.com. Archived from the original on July 27, 2014. Retrieved December 6, 2014.

- ↑ "Local news from The Sun News in Myrtle Beach SC | MyrtleBeachOnline.com". myrtlebeachonline.com. Retrieved 2014-12-06.

- ↑ "Tabor-Loris Tribune – September 17, 2014". tabor-loris.com. Archived from the original on October 12, 2014. Retrieved December 6, 2014.

- ↑ Justin Smith (2014-10-07). "Commissioner could benefit from railroad receiving county incent – WECT TV6-WECT.com:News, weather & sports Wilmington, NC". wect.com. Retrieved 2014-12-06.

- ↑ "CONWAY: Horry County Council approves $1.8 m commitment to help purchase Carolina Southern Railroad | Local News | MyrtleBeachOnline.com". myrtlebeachonline.com. Archived from the original on 2014-10-13. Retrieved 2014-12-06.

- ↑ "Carolina Southern could roll again by next spring | Business | MyrtleBeachOnline.com". myrtlebeachonline.com. Archived from the original on 2014-10-16. Retrieved 2014-12-06.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-09-10. Retrieved 2015-11-04.

- ↑ "Done Deal: Railroad that serves Columbus County changes hands". Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ↑ Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved 2018-03-15.

- 1 2 http://www.wect.com/clip/11957953/new-animal-control-director-seeks-to-improve-columbus-co-shelter%5Bpermanent+dead+link%5D

- ↑ "Columbus County > Departments > Animal Control". columbusco.org. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ↑ TV3, WWAY (24 June 2015). "Columbus County Animal Shelter fined again - WWAY TV". Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- 1 2 "NCDA&CS Veterinary Division Animal Welfare Section Civil Penalties and Other Legal Issues". www.ncagr.gov. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ↑

- ↑ "Log In or Sign Up to View". www.facebook.com. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ↑ "Columbus County Public Library System Copy". Columbus County Public Library System Copy. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ↑ "North Carolina Division of Prisons". www.doc.state.nc.us. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ↑ Office, Columbus County Sheriff's. "Home". columbuscountysheriff.com. Retrieved 15 March 2018.