New Belgrade

| New Belgrade Нови Београд Novi Beograd | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Municipality | |||

New Belgrade at night | |||

| |||

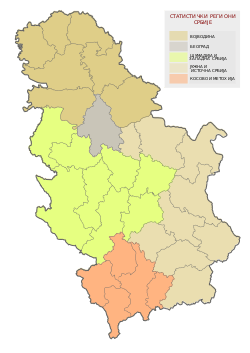

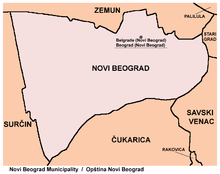

Location of New Belgrade within the city of Belgrade | |||

| Country |

| ||

| City | Belgrade | ||

| Status | Municipality | ||

| Settlements | 1 | ||

| Government | |||

| • Type | Municipality of Belgrade | ||

| • Mun. president | Aleksandar Šapić (Ind.) | ||

| • Ruling coalition | Šapić list - SRS (supported also by DS) | ||

| Area | |||

| • Total | 40.96 km2 (15.81 sq mi) | ||

| Population (2011) | |||

| • Total | 212,104 | ||

| • Density | 5,200/km2 (13,000/sq mi) | ||

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) | ||

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) | ||

| Postal code | 11070 | ||

| Area code(s) | +381(0)11 | ||

| Car plates | BG | ||

| Website |

www | ||

New Belgrade (Serbian: Нови Београд/Novi Beograd, pronounced [nôʋiː beǒɡrad]) is a municipality of the city of Belgrade. It is the central business district in Serbia and one of the major ones in Southeast Europe. It was a planned municipality, built since 1948 in a previously uninhabited area on the left bank of the Sava river, opposite old Belgrade. In recent years, it has become the central business district of Belgrade and its fastest developing area, with many businesses moving to the new part of the city, due to more modern infrastructure and larger available space. With 212,104 inhabitants,[1] it is the second most populous municipality of Serbia after Novi Sad.

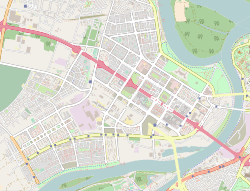

Geography

New Belgrade is located on the left bank of the Sava River, in the easternmost part of the Srem region. Administratively, its northeastern section touches the right bank of the Danube, right before the Sava's confluence. It is generally located west of the 'Old' Belgrade to which it is connected by six bridges (Gazela, Branko's Bridge, Old Railway Bridge, New Railway Bridge and Ada Bridge). European route E75, with five grade separations, including a new double-looped one at the Belgrade Arena, goes right through the middle of the settlement.

The municipality of New Belgrade covers an area of 40.74 square kilometres (15.73 sq mi). Its terrain is flat, which poses a high contrast to the old Belgrade, built on 32 hills total. Except for its western section, Bežanija, New Belgrade is built on a terrain that was essentially a swamp when construction of the new city began in 1948. For years, kilometers-long conveyor belts were transporting sand from the Danube's island of Malo Ratno Ostrvo, almost completely destroying it in the process, and only a small, narrow strip of wooded land remains today. Thus, it is romantically said that New Belgrade is actually built on an island.

Other geographic features are the peninsula of Mala Ciganlija and the island of Ada Međica, both on the Sava and the bay of Zimovnik (winter shelter), engulfed by Mala Ciganlija, with the facilities of the Beograd shipyard. The loess slope of Bežanijska Kosa is located in the western part of the municipality, while in the southern, the Galovica river canal flows into the Sava.

Though it has no forests in the real sense, of all municipalities of Belgrade, Novi Beograd has the largest green areas, with a total of 3.47 square kilometres (1.34 sq mi), or 8.5% of the territory.[2] Majority of these are made up of the large Ušće park. The latest addition to Belgrade parks, Park Republika Srpska from 2008, is also located in the municipality.

There are no separate settlements within the municipality, as the entire area administratively belongs to the Belgrade City proper and is statistically classified as part of Belgrade (Beograd-deo). The area located around the municipal assembly building and the nearby roundabout is considered to be New Belgrade's center.

As it was planned and constructed, New Belgrade was divided into blocks. Currently, there are 72 blocks (with several sub-blocks, like 70-a, etc.). Old core of the village of Bežanija, Ada Međica, and Mala Ciganlija, as well as the area along the highway west of Bežanijska Kosa are not divided into blocks, while due to the administrative borders changes, some of the blocks (9, 9-a, 9-b, 11, 11-c and 50) belong to the municipality of Zemun, extending north of New Belgrade as one continuous built-up area.

In September 2018, Belgrade's mayor Zoran Radojičić announced that the construction of a dam on the Danube, in the Zemun-New Belgrade area, will start soon. The dam should protect the city during the high water levels.[3][4] Such project was never mentioned before, nor it was clear how and where it will be constructed, or if it's feasible at all. Radojičić clarified after a while that he was referring to the temporary, mobile flood wall. The wall will be 50 cm (20 in) high and 5 km (3.1 mi) long, stretching from the Branko's Bridge across the Sava and the neighborhood of Ušće, to the Radecki restaurant on the Danube's bank in the Zemun's Gardoš neighborhood. In case of emergency, the panels will be placed on the existing construction. The construction is scheduled to start in 2019 and to finish in 2020.[5]

History

Early history

Bežanija is the oldest part of today's New Belgrade, where a settlement existed from the neolithic to the Roman period.

In the book Kruševski pomenik from 1713, which is kept in the Dobrun monastery near Višegrad, settlement of Bežanija was mentioned for the first time under its present name as far as 1512, as a small village with 32 houses, populated by Serbs.[6] In this time, the village was under the administration of the medieval Kingdom of Hungary, and was part of the Syrmia County. The inhabitants of the village crossed the Sava river and settled in Syrmia after fleeing the fall of the medieval Serbian Despotate under the hands of the Ottoman Empire (hence the name bežanija, "refugee camp" in archaic Serbian).

In 1521, the village became part of the Ottoman Empire. From 1527 to 1530, Bežanija was part of Radoslav Čelnik's Duchy of Syrmia, an Ottoman vassal, until its subsequent organization into the Ottoman Sanjak of Syrmia. The Habsburg Monarchy conquered it temporarily during the Great Turkish War (1689-1691), but it remained under Ottoman administration until 1718. In 1718, the village became part of the Habsburg Monarchy and was placed under military administration. It was part of the Habsburg Military Frontier (Petrovaradin regiment of Slavonian Krajina). During the 17th and 18th century, hunger and constant Turkish intrusions devastated the village, but it was constantly being repopulated by the refugees from central Serbia. In 1810, population census counted 115, mostly Serbian households. By the 1850s, Austrians colonized a large number of Germans in Bežanija.[6] In 1848-1849 it was part of the Serbian Vojvodina, an ethnic Serb autonomous region within the Austrian Empire, but in 1849 was again placed under administration of the Military Frontier.

As the Frontier was abolished in 1881-1882, it became part of the Syrmia County within the autonomous Habsburg kingdom Croatia-Slavonia, which was located within the Hungarian part of the Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary. In 1910, the largest ethnic group in the village were Serbs,[7] while other sizable ethnic groups were Germans, Hungarians and Croats. After dissolution of Austria-Hungary, in autumn of 1918, Bežanija became part of the newly formed State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs. On 24 November 1918, as part of Syrmia region, the village became part of the Kingdom of Serbia, and on December 1, it became part of the newly formed Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (future Yugoslavia).

From 1918 to 1922, the village was part of the Syrmia County and from 1922 to 1929 part of the Syrmia Oblast. Bežanija became part of the wider Belgrade area for the first time in 1929 after coup d'état conducted by the king Alexander I of Yugoslavia, who, among other things, draw a new map of Yugoslavia's administrative division creating a new administrative unit Uprava grada Beograda or Administration of the City of Belgrade which comprised Belgrade, Zemun (with Bežanija) and Pančevo.

Inter-war period

Between the two world wars of the 20th century, communities sprung up closer to the Sava river in Staro Sajmište and Novo Naselje. The idea of building a new settlement across the Sava was officially presented in 1922 and the first urbanization plans for Belgrade's expansion to the Sava's left bank were drawn up in 1923, but a lack of either funds or the manpower needed to drain out the swampy terrain put them on hold indefinitely. The project was conceived by Đorđe Kovljanski and it included an idea of creating an island from the Savamala neighborhood (he coined the term "Sava amphitheatre") in old Belgrade.[8] He even envisioned the bridge across the northern tip of Ada Ciganlija, across the Sava, which realized in 2012.[9] In 1924 Petar Kokotović opened a kafana on Tošin Bunar with the prophetic name Novi Beograd. After 1945 Kokotović was president of the local community of Novo Naselje–Bežanija which later grew into the municipality of Novi Beograd.[10] In 1924 an airport was built in Bežanija and in 1928 the Rogožerski factory was constructed. In 1934 plans were expanded to include the creation of a new urban tissue which connected Belgrade and Zemun, as Zemun was administratively annexed to the city of Belgrade in 1929, losing separate city status in 1934. A King Alexander Bridge was also built over the Sava River and a tram line connecting Belgrade and Zemun was established. Also, a Zemun airport was built.

A sandy beach with the cabins, kafanas and barracks, used as sheds by the fishermen, occupied the area of the modern Ušće quay, north of the Branko's Bridge. It was one of the favorite vacation spots of Belgraders during Interbellum. People were transported from the city by small boats and the starting point was a small kafana "Malo pristanište" in Savamala. Occupying the left bank of the Sava, it was on the location of the access ramp for the future King Alexander Bridge so it had to be removed. The objects were demolished manually, including numerous kafanas: "Ostend", "Zdravlje", "Abadžija", "Jadran", "Krf", "Dubrovnik", "Adrija", etc. The only one that wasn't demolished was "Nica", predecessor of the modern Ušće restaurant. In total, 20 proper objects and 2,000 cabins, barracks, sheds, etc. were demolished, jointly by the municipalities of Zemun and Bežanija, which owned half of the land each, and the proprietors of the objects. The plan was to build an embankment instead. However, the beach itself survived the construction of the bridge in 1934 as it only made access easier. The beach was finally closed in 1938 when the construction of the embankment began.[11] The beach itself was called Nica (Serbian for Nice, in France) after one of the kafanas.[12]

A group of Danish investors offered to the city government their project of constructing a new settlement between Belgrade and Zemun, on the left bank of the Sava. In February 1937 they sent a very elaborate proposal with maps to the then mayor of Belgrade, Vlada Ilić. Danes offered to do it for 94 million 1937 dinars and the city administration replied that the project got their fullest attention, but that citizens of Belgrade and Zemun should have a say, too, about this new settlement.[13] In August Danish investors held a meeting with mayor Ilić. This time, they offered to build the entire modern neighborhood for free, but to retain the right to sell the lots to private buyers who are interested into building houses in the neighborhood, in the total amount of over 80 million dinars, while the city would remain the owner of the land.[14] A contract was signed on 24 February 1938. Danish representatives announced that their ships will reach Belgrade by 12 to 15 May 1938. Among them, there was one special ship. It was to dredge the bottom of the Danube in the vicinity of Great War Island and to eject the dredged earthy materials through pipes in the swamp, filling it. It was planned to fill the area on the right side of the Zemun road, which extended across the King Alexander Bridge across the Sava. It was expected that the work, estimated at 30 million dinars, will be finished by 1940 when the area was to become a nice, dried and elevated filled terrain suitable for the start of the construction of the "newest Belgrade". The project was described as the "displacement of the Sava's confluence into the Danube".[15] Ultimately, the deal never materialized.

In 1930s members of Belgrade's affluent elite began to buy land from the villagers of Bežanija, which at that time, administratively spread all the way to the King Alexander Bridge, which was a dividing point between Bežanija and Zemun. From 1933 a settlement, consisting mostly of individual villas, began to develop. Also, a group of Belarus emigrants built several small buildings, mostly rented by the carters who carried goods across the river. As the settlement, which became known as New Belgrade, was built without building permits, authorities threatened to demolish it, but in 1940 government officially "legalized the informal settlement of New Belgrade".[16] Prior to that, the city already semi-officially recognized the new settlement, as it helped with building its streets and pathways. By 1939 it already had several thousands inhabitants, a representative in the city hall, and was unofficially called New Belgrade.[17]

In 1938, for the purpose of hosting Belgrade Fair, a complex of buildings was erected next to the already existing community. Spread over 15 thousand square metres, it hosted fairs and exhibitions designed to show off the Kingdom of Yugoslavia's developing economy. Also this year, the municipality of Belgrade signed a contract with two Danish construction companies, Kampsax and Højgaard & Schultz, to build the new neighbourhood. Engineer Branislav Nešić was entrusted with leading the project. He even continued his involvement on the project after 1941 when the Nazis conquered, occupied, and dissolved the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. Because of this, the new communist authorities who came to power after 1945 put Nešić on trial as a collaborator. As the complex never hosted any fairs again and the new Belgrade Fair was built across the river, the area became known as Staro Sajmište ("Old Fairground").

On 22 February 1941, mayor of Belgrade Jovan Tomić and architect Dragiša Brašovan held a press conference, announcing plans for the future. The plans were made for New Belgrade and the Sava's bank in "Old" Belgrade. The new town was to be built on 6 km2 (2.3 sq mi) and have 500,000 inhabitants, even though the entire Belgrade at that time had a bit over 350,000 people. Tomić issued a ban for the private owners to purchase the land, so that all land designated for the future town will remain city owned. He also asked from the state government to banish all private land owners on the Sava's right bank, located between the Belgrade Main railway station and the river and to confiscate the land. Further plans included the filling of the arm of the Danube and turning the Great War Island into the peninsula and erection of the monumental memorial on it. The project also included two new bridges across the Sava, which would connect the old and the new part of the city, one on the location of the modern Gazela bridge (which was built in 1970) and another in the continuation of the Nemanjina Street. Because of the latter bridge, Tomić planned to demolish the building of the Belgrade Main railway station and relocate the facility in the neighborhood of Prokop, thus clearing further 1 km2 (0.39 sq mi) of space for the commercial facilities.[18] Construction of the new railway station in Prokop indeed began, but in 1977 and as of 2018 is still not finished, though in 2017 it took over the domestic transportation.

World War II

In 1941, German forces occupied much of Yugoslavia. Nazi secret police, Gestapo, took over the fairgrounds (Sajmište). They encircled it with several rings of barbed wire turning it into a "collection centre". It eventually became an extermination camp, the Sajmište concentration camp. Until May 1942 it was mostly used to kill off Jews from Belgrade and other parts of Serbia, and from April 1942 onwards, it also held political prisoners. Executions of captured prisoners lasted as long as the camp existed. November 1946 report released by the Yugoslav State Commission for Crimes of Occupiers and their Collaborators claims that close to 100,000 prisoners came through the Sajmište's gates. It is estimated that around 48,000 people perished inside the camp.

Rapid development

First sketches of urbanistic plans were developed by Nikola Dobrović in 1946 and preparations began in 1947.[8] Architect Mihajlo Mitrović called New Belgrade "an obsessive vision of Dobrović".[19] A monograph on the construction of New Belgrade by Slobodan Ristanović described what the area looked liked before the city was built: "In the thick reeds and bulrush there were many snakes and frogs, fishes and leeches. Above this swamp, flocks of birds were circling and the swarms of mosquitos and other insects were going up and down. Just few houses and occasional shack in the marsh around the Zemun airport, so as the derelict neighborhood of Staro Sajmište attested the human presence in that inhospitable ambience."[20]

It was on 11 April 1948, three years after World War II ended, that the ground was broken on a huge construction project, which would give birth to what is known today as New Belgrade. During first three years of construction alone, over 200,000 workers and engineers from all over the freshly liberated country took part in the building process. Work brigades, parts of the Youth work actions made up of villagers brought in from rural Serbia provided most of the manual labour. Even high school and university student volunteers took part. It was backbreaking labour that went on day and night. With no notable technological tools to speak of, mixing of concrete and spreading of sand were done by hand with horse carriages only used for extremely heavy lifting. The concept of Youth work actions continued up to 1990 and the objects built this way include the Studentski Grad, Block 7, Block 7a, Paviljoni, Gazela Bridge, Hospital Bežanijska Kosa, SIV, etc.[20]

Before the actual construction started, the terrain was evenly covered with sand from the Sava and the Danube rivers in an effort to dry out the land and raise it above the reach of flooding and underground streams.

Among the first to go up was the SIV 1 building, which housed the Federal Executive Council (SIV). The building has 75,000 square metres of usable space. Built during the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, it was also used during the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia before its dissolution. The building was renamed to Palata Srbije, and now houses some departments of the Serbian government.

First buildings for classic residential purposes were built as pavilions close to the area known as Tošin Bunar (Toša's Well). Studentski Grad (Student City) complex was also built around the same time to meet the residence needs of the growing University of Belgrade student body that came from other parts of Yugoslavia.

Buildings sprung up one after another and by 1952, New Belgrade was officially a municipality. In 1955 the municipality of Bežanija was annexed to New Belgrade. It was for years the biggest construction site in Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia and a huge source of pride for country's communist authorities that oversaw the project.

In general, development of New Belgrade is divided in four major phases, all of which have a landmark buildings constructed in that periods:[8]

a) First phase (1948-1958)

- completion of the first residential blocks, 7 and 7a;

- founding of the first local community “Pionor” (now Paviljoni);

- completion of the Studentski Grad (1949-1955).

b) Second phase (1958-1968)

- Friendhip Park and SIV completed in 1961;

- Building of the Municipality of New Belgrade finished (1961–64);

- Museum of Contemporary Art finished in 1965;

- Ušće Tower, completed in 1964

- Hotel Jugoslavija Opened 1968

c) Third phase (1968-2000)

- Residential blocks 21, 22, 23, 24, 28, 29, 30, 45 and 70 (first half of the 1970s)

- Sava Centar with Hotel Intercontinental (now Crowne Plaza Belgrade) opened in 1977.

- Western City Gate finished in 1980

d) Modern period (from 2000)

- Belgrade Arena, finished in 2004

- Delta City, opened in 2007

- Belville Complex, opened in 2009

- Sava City Opened in 2009

- Airport City Belgrade

- Ušće Shopping Mall, opened in 2009

Neighbourhoods

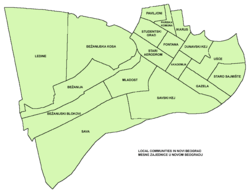

Just like other municipalities of Serbia, New Belgrade is further divided into local communities (Serbian: mesna zajednica). Apart from Bežanija and Staro Sajmište, no other neighbourhoods have historical or traditional names, as Novi Beograd did not exist as such. However, in the five decades of its existence, some of its parts gradually became known as distinct neighborhoods of their own.

List of the neighborhoods of New Belgrade:

|

|

Architecture

Ikarus building

As of 2018, one of the oldest surviving buildings in New Belgrade is the former administrative building of the Ikarus company, built in 1938. It is located in the modern Block 9-a, at 3-a Gramšijeva street. In June 2017 it was announced that the building will be demolished so that private investor can build a highrise instead. Locals organized in an effort to adapt the building into the museum instead.[21] City government, which in 2015 stated that the building will not be demolished, issued a demolition permit in February 2018. Citizen protested, demolished the construction hoarding and physically preventing the investor to destroy the building, so police intervened.[22] Investor then posted a board which showed that the original building will be preserved but vastly expanded and superstructured (total of 8.500 m2 (91.49 sq ft) floor area). Still, a heavy demolition machinery was brought so citizens protested again in March. Inheritors of the pre-World War II owners of the "Ikarus" company, which was nationalized after 1945, applied for the restitution.[23]

The administrative building of the former airplane factory was a symbol of the industrial development of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia during the Interbellum. Apart from being one of the oldest preserved objects in New Belgrade, it was the only representative of the Art Deco in the municipality. Citizens proposed that the building might be adapted into the Museum of New Belgrade or a branch of the Museum of Aviation. The building was not protected by the law.[23] Still, the building was demolished in July 2018.[24]

After 1945

Architects who are most deserving for New Belgrade's development are Uroš Martinović, Milutin Glavički, Milosav Mitić, Dušan Milenković and Leonid Lenarčić. They drafted the city's regulatory plan in 1962 which encompassed all the previous ideas, solutions and propositions.[8]

New Belgrade developed on Le Corbusier's principles of the "sun city", which includes lots of green areas and infrastructure which can easily be upgraded. In general, city developed in the style of urban modern architecture and is considered to be a major representative of that style, along with Brasilia in Brazil, Chandigarh in India and Velenje in Slovenia.[8]

Characteristic for the buildings in New Belgrade is that many of them got nicknames. Best known ones include:[8]

- "Šest kaplara" (Six corporals), Block 21, as most apartments were settled by the military personnel and their families;

- "Televizorka" (TV-screen building), Block 28, due to the look of its windows;

- "Tri sestre" (Three sisters), Fontana, three identical buildings;

- "Potkovica" (Horseshoe), Block 28, due to its shape;

- "Pendrek", "Sirotica" and "Besna kobila" (Police baton, Poor girl and Mad mare), near Studentski Grad, as the first was populated by the policemen's families, second by the socially endangered and third by the well-to-do members of the Communist party;

- "Mercedes", Block 38, three connected buildings in the shape of the car's logo;

- "Lamela" or "Meander", Block 21; next to "Šest kaplara", with 972.5 m (3,191 ft) it is the longest residential building in former Yugoslavia. It was built from 1960 to 1966 and officially named "B-7";[25]

Demographics

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1948 | 9,195 | — |

| 1953 | 11,339 | +23.3% |

| 1961 | 33,347 | +194.1% |

| 1971 | 92,500 | +177.4% |

| 1981 | 173,541 | +87.6% |

| 1991 | 218,633 | +26.0% |

| 2002 | 217,773 | −0.4% |

| 2011 | 212,104 | −2.6% |

| 2014 | 214,506 | +1.1% |

| Source: [26] | ||

Ever since the construction began in 1948, New Belgrade experienced explosive population growth, but this trend stopped during the 1990s and became negative. As of 2011, the municipality of New Belgrade has a population of 212,104 inhabitants.

Ethnic groups

The ethnic composition of the municipality (as of 2011):[27]

| Ethnic group | Population |

|---|---|

| Serbs | 190,834 |

| Romani | 3,020 |

| Montenegrins | 2,115 |

| Croats | 1,812 |

| Yugoslavs | 1,706 |

| Macedonians | 1,221 |

| Muslims | 813 |

| Slovenians | 394 |

| Bosniaks | 343 |

| Hungarians | 322 |

| Gorani | 304 |

| Russians | 263 |

| Albanians | 223 |

| Slovaks | 177 |

| Bulgarians | 111 |

| Romanians | 90 |

| Others | 8,356 |

| Total | 212,104 |

Economy

As all of the socialist governments considered heavy industry to be the driving force of the entire economy, it for decades dominated New Belgrade's economy too: Industry of Machinery and Tractors (IMT), Metallic cast iron factory (FOM), shipyard "Beograd" (formerly "Tito"), large heating plant in Savski Nasip, "MINEL" electro-construction company, etc. All of these complexes will be removed and develop in business and residential areas.

In the 1990s with the collapse of gigantic state-owned companies, New Belgrade's local economy bounced back by switching to commercial facilities, with dozens of shopping malls and entire commercial sections such as Mercator Center Belgrade, Ušće Mall, Delta City Belgrade etc. These activities are further enhanced in the 2000s (decade). The 'Open Shopping Mall' or the Belgrade's flea market is also located in New Belgrade.

New Belgrade became the main business district in Serbia and one of major in Southeast Europe. Many companies choose New Belgrade for regional centers such as IKEA, Energoprojekt holding, Delta Holding, MK Group, DHL, Air Serbia, OMV, Siemens, Société Générale, Telekom Srbija, Telenor Serbia, Unilever, Vip mobile, Yugoimport SDPR, Ericsson, Colliers International, CB Richard Ellis, SNC-Lavalin, Hewlett-Packard, Huawei, Ernst & Young and Arabtec.[28] The Belgrade Stock Exchange is also located in New Belgrade. Other notable structures built not too long afterwards include convention and congress hall Sava Center, Hotel Jugoslavija, Genex condominium, Genex Tower sports and concert venues Hala Sportova and Belgrade Arena, and 4 and 5-star hotels Crowne Plaza Belgrade, Holiday Inn, Hyatt Regency, Tulip Inn etc., with around 1700 rooms,... Many structures are currently under construction like Airport City Belgrade, Elektroprivreda Srbije HQ., West 65 business-residential complex, etc.

Many IT companies choose New Belgrade as regional center like NCR Corporation, Cisco Systems, SAP AG, Acer, ComTrade Group, Hewlett-Packard, Huawei, Samsung. One of Microsoft's development centers is also located in New Belgrade.

Currently finished projects in New Belgrade are Delta City, Sava City, Univerzitetsko Selo, Ada Bridge, Intesa HQ and Ušće Tower.

The following table gives a preview of total number of employed people per their core activity (as of 2016):[29]

| Activity | Total |

|---|---|

| Agriculture, forestry and fishing | 551 |

| Mining | 269 |

| Processing industry | 6,766 |

| Distribution of power, gas and water | 1,524 |

| Distribution of water and water waste management | 548 |

| Construction | 7,260 |

| Wholesale and retail, repair | 28,377 |

| Traffic, storage and communication | 6,611 |

| Hotels and restaurants | 4,462 |

| Media and telecommunications | 10,351 |

| Finance and insurance | 10,682 |

| Property stock and charter | 852 |

| Professional, scientific, innovative and technical activities | 14,452 |

| Administrative and other services | 17,814 |

| Administration and social assurance | 10,996 |

| Education | 3,504 |

| Healthcare and social work | 4,347 |

| Art, leisure and recreation | 1,763 |

| Other services | 2,187 |

| Total | 133,319 |

Transportation

Railways and trams in New Belgrade | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Several important thoroughfares run through New Belgrade, along with numerous wide boulevards that criss-cross most of its territory.

The A3 motorway (carrying E70 and E75) runs northwest to southeast, with five exits. It crosses the Sava River via Gazela Bridge. New Belgrade is served by two more road bridges – Branko's Bridge and Ada Bridge, and by the road-tram Old Sava Bridge.

With services started in 1985, tram transportation plays an important role in New Belgrade transportation, despite it having just two tracks which mostly run along the several kilometers long Jurija Gagarina street. Four tram lines serve the municipality (7, 9, 11 and 13) and there is a tram depot in Đorđa Stanojevića street.

Since the 1970s, New Belgrade has been served by two railway lines connecting it to the city center and by one line to Zemun. Virtually the entire length of these lines is on an embankment, with an elevated segment on the approach to the New Railroad Bridge, and a tunnel toward Zemun. Two railway stations exist, the larger being the Novi Beograd which is located above the Antifašističke borbe street and is served by BG Voz and other local and international lines. The other railway station is Tošin Bunar which is a 2-track stop located just outside Bežanija tunnel.

The international fairway on the Sava runs along the banks of New Belgrade. The only public river transportation is run by two seasonal boat lines from Blok 70 to Ada Ciganlija, and by another one connecting Blok 44 to Ada Međica.

Belgrade's main shipyard is located on New Belgrade's Sava bank. On the Danube, the base of the 2nd River Squadron of Serbian River Flotilla is located next to the confluence of the Sava, which restricts navigation around Little War Island.

From 1927 to 1964 the international Dojno polje Airport was located on the territory of today's New Belgrade.

Politics

Historical Presidents of the Municipal Assembly since 1952:[30]

- 1952–1953: Stevan Galogaža

- 1953–1955: Mile Vukmirović

- 1955–1956: Živko Vladisavljević

- 1956–1957: Ilija Radenko

- 1957–1962: Ljubinko Pantelić

- 1962–1965: Jova Marić

- 1965–1969: Pero Kovačević (born 1923)

- 1969–1979: Novica Blagojević (died 1979)

- 1979–1982: Milan Komnenić

- 1982–1986: Andreja Tejić

- 1986–1989: Toma Marković

- 1989–2000: Čedomir Ždrnja (born 1936)

- 2000–2008: Željko Ožegović (born 1962)

- 2008–2012: Nenad Milenković (born 1972)

- 2012–present: Aleksandar Šapić (born 1978)

Culture and education

For a settlement of such size, New Belgrade has some unusual cultural characteristics, influenced by the Yugoslav communists' ideas how a new and modern city should look like. If it can be understood why there were no churches built, a fact that a city of 250,000 has no theaters and only one museum (out of the residential area) is much less comprehensible, underlying the decades long Belgrader's feel of New Belgrade being nothing more but a big dormitory.

Museum of Contemporary Art is located in Ušće which is also projected by the city government as the location of the future Belgrade Opera. The issue became highly controversial in the 2000s (decade) as the general feel of the population, ensemble of the opera and most prominent architects and artists is that it is a very bad location for the opera, while the city government stubbornly insists against the popular wishes.

For decades, the only church in the municipality was an old Church of Saint George in Bežanija. Construction of the new church in Bežanijska Kosa, the Church of Saint Basil of Ostrog, began in 1996, while the construction of the Church of Saint Demetrius of Salonica, which is considered the first church in New Belgrade, began in 1998. Both are still not completed.

Schools

Education fared much better than culture, as there are numerous elementary and high schools, as well as University of Belgrade's residential campus - Studentski Grad.

List of schools in New Belgrade:

- Ninth Belgrade Gymnasium

- Tenth Belgrade Gymnasium

- University of Arts' Faculty of Dramatic Arts (FDU)

- Megatrend University

- Graphic Design Secondary School

- Polytechnical Academy

- Technical School

- Russian School

Night life

New Belgrade offers rich night life along the banks of Sava and Danube, right up to the point where the two rivers meet. What started mostly as raft-like social clubs for river fishermen in the 1980s expanded into large floats offering food and drink with live turbo folk performances during the 1990s.

Today, it is unlikely that one would walk a 100-metre (330-foot) stretch along the rivers without encountering a float. Some of them grew into entire entertainment complexes rivaling clubs in Belgrade's downtown core. While most of the floats used to be synonymous with turbo folk in what was essentially a stereotypical kafana setting, a recent trend saw many turned into full-fledged clubs on water with elaborate events involving world-famous DJs spinning live music.

Public image

Not much attention was paid to detail and subtlety when New Belgrade was being built during the late 1940s and early 1950s. The objective was clearly to put up as many buildings as fast as possible, in order to accommodate a displaced and growing post-World War II population that was in the middle of a baby boom. This across-the-board brutalist architectural approach led to many apartment buildings and even entire residential blocks looking monumental in an awkward way. Although the problem has been alleviated to certain extent in recent decades by addition of some modern expansion (Hyatt and Intercontinental hotels, luxury Genex condos, Ušće Tower, Belgrade Arena, Delta City, etc.), many still complain about what they see as New Belgrade's "grayness" and "drabness". They often use the derisive term "spavaonica" ("dormitory") to underscore their view of New Belgrade as a place that does not inspire creative living nor encourage healthy human interaction, and is only good for overnight sleep at the end of the hard day's work. This opinion has found its way into Serbian pop culture as well.

In an early 1980s track called 'Neću da živim u Bloku 65', popular Serbian band Riblja čorba sings about a depressed individual who hates the world because he's surrounded by the concrete of New Belgrade, while a more recent local cinematic trend sees New Belgrade presented somewhat clumsily as the Serbian version of New York ghettos like those found in Harlem, Brooklyn and The Bronx. The most obvious example of the latter would be 2002 movie 1 na 1, which portrays a bunch of Serbian teenagers who rap, shoot guns, play street basketball and seem to blame many of their woes on living in New Belgrade. Other films like Apsolutnih 100 and The Wounds also implicitly paint New Belgrade in the negative light but they have a more coherent point of view and place their stories within the context of the 1990s when war and international isolation truly did push some Serbs, including those inhabiting New Belgrade, to desperate acts.

Twin towns – sister cities

New Belgrade is twinned with the following cities and municipalities:[31]

Notable people

- Aleksandar Vučić, politician

- Zoran Đinđić, politician

- Nemanja Bjelica, basketballer

- Aleksandar Šapić, politician, former waterpoloist

- Branka Katić, actress

See also

References

Bibliography

Notes

- ↑ "Microsoft Word - Tab-2_10112011.doc" (PDF). Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- ↑ Daliborka Mučibabić (26 April 2008). "Srpska prestonica u brojkama" (in Serbian). Politika. Retrieved 25 April 2014.

- ↑ J.D. (18 September 2018). "Gradiće se brana na Dunavu!" [A dam will be built on the Danube]. Večernje Novosti (in Serbian).

- ↑ Tanjug (17 September 2018). "Uskoro gradnja brane na Dunavu kod Novog Beograda" [Soon building of the dam on the Danube at New Belgrade]. Blic (in Serbian).

- ↑ Dejan Aleksić (22 September 2018). "Umesto džakova, mobilna brana protiv poplava" [Mobile dam against the flood, instead of sandbags]. Politika (in Serbian).

- 1 2 Nikola Belić (11 June 2012). "Bežanija, od imperije do tranzicije" (in Serbian). Politika.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-10-07. Retrieved 2011-06-28.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Daliborka Mučibabić, Nikola Belić (11 April 2013), "Ponos socijalističke gradnje – centar biznisa i trgovine", Politika (in Serbian), p. 19

- ↑ Nikola Belić (4 January 2012), "Gorostasi nad rekama kao svedoci istorije", Politika (in Serbian)

- ↑ "Bitka za Beograd", Politika (in Serbian), p. 11, 2008-04-11

- ↑ Zoran Nikolić (14 January 2015). "Beogradske priče: Seoba sa savskog kupališta" [Belgrade stories: Moving out from the Sava beach] (in Serbian). Večernje Novosti.

- ↑ Daliborka Mučibabić & Nikola Belić (11 April 2013), "Ponos socijalističke gradnje – centar biznisa i trgovine", Politika (in Serbian), p. 19

- ↑ "Danci nude da naspu i urede Novi Beograd između Beograda i Zemuna", Politika (in Serbian), 4 March 1937

- ↑ "Danci i dalje nude da podignu naselje između Zemunskog mosta i Zemuna", Politika (in Serbian), 29 August 1937

- ↑ "Premešta se ušće Save u Dunav", Politika (in Serbian), 17 April 1938

- ↑ Zoran Nikolić (9 March 2016). "Beogradske priče – Novi Beograd rođen na Starom sajmu" (in Serbian). Večernje Novosti.

- ↑ ""Elitno" naselje "Novi Beograd" napreduje", Politika (in Serbian), 12 June 1939

- ↑ Nenad Novak Stefanović (29 December 2017), "Dom oca Novog Beograda" [Home of the New Belgrade's father], Politika-Moja kuća (in Serbian), p. 1

- ↑ Mihajlo Mitrović (15 October 2010), "Savograd: helidrom za ptice i feniksa", Politika (in Serbian)

- 1 2 Ana Vuković, Dejan Aleksić (11 April 2018). "Sedam decenija grada brigadira" [Seven decades of the brigadiers' city]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 14.

- ↑ Ana Vuković (21 June 2017), "Stanari sanjaju muzej, investitor planira šestospratnicu", Politika (in Serbian), p. 17

- ↑ U. Miletić (22 February 2018). "Inicijativa Ne da(vi)mo Beograd : Nećemo dozvoliti da zgradu Ikarusa sruše" [Initiative "Ne da(vi)mo Beograd": We will not allow the demolition of the "Ikarus" building] (in Serbian). Danas.

- 1 2 Ana Vuković, Daliborka Mučibabić (5 March 2018). "Komšije uplašene za sudbinu zgrade "Ikarusa"" [Neighbors afraid for the future of the "Ikarus" building]. Politika (in Serbian).

- ↑ "Београд: Срушена управна зграда Икаруса, некадашње фабрике авиона и једна од најстаријих зграда на Новом Београду" [Belgrade: the administrative building of Ikarus, former airplane factory and one of the oldest buildings in New Belgrade, was demolished] (in Serbian). Nova srpska politička misao. 3 July 2018.

- ↑ Goran V. Anđelković (2 June 2017), "U odbranu meandra", Politika (in Serbian)

- ↑ "2011 Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in the Republic of Serbia" (PDF). stat.gov.rs. Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- ↑ "ETHNICITY Data by municipalities and cities" (PDF). stat.gov.rs. Statistical Office of Serbia. Retrieved 1 March 2018.

- ↑ "Iz Beograda osvajaju Balkan" (in Serbian). Večernje novosti. 25 January 2014.

- ↑ "ОПШТИНЕ И РЕГИОНИ У РЕПУБЛИЦИ СРБИЈИ, 2017" (PDF). stat.gov.rs (in Serbian). Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ↑ "Od močvare do poslovnog centra".

- ↑ "Međunarodna saradnja" (in Serbian). novibeograd.rs.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to New Belgrade. |