Studentski Trg

| Studentski Trg Студентски Трг | |

|---|---|

| Urban neighbourhood | |

| |

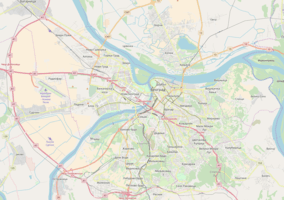

Studentski Trg Location within Belgrade | |

| Coordinates: 44°49′08″N 20°27′27″E / 44.818918°N 20.457442°ECoordinates: 44°49′08″N 20°27′27″E / 44.818918°N 20.457442°E | |

| Country |

|

| Region | Belgrade |

| Municipality | Stari Grad |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Area code | +381(0)11 |

| Car plates | BG |

Studentski Trg or Students Square (Serbian Cyrillic: Студентски Трг) is one of the central town squares and an urban neighborhood of Belgrade, the capital of Serbia. It is located in Belgrade's municipality of Stari Grad.

Location

Studentski Trg is located halfway between the Republic Square (to the east) and the Kalemegdan park-fortress (to the west). It is adjacent to the Academy Park. To the north it extends into the neighborhood of (Upper) Dorćol, while the pedestrian zone of Knez Mihailova is located to the south.[1][2]

History

Roman period

Northern section of the Academy Park was excavated in 1968 in the project of building a furnace oil tank for the boiler room of the Belgrade's City Committee of the League of Communists located nearby. Under the lawn, the remnants of the ancient Roman thermae were discovered, including the frigidarium (room with the cold water), laconicum (room with the warm water where people would sweat and prepare) and caldarium (room with the two pools of hot water). The site became an archaeological dig in 1969 and 8 rooms in total were discovered, including the remains of the brick furnace which heated the water. It was a public unisex bath dated to 3rd or 4th century. The entire area of the park is actually within the borders of the "Protected zone of Roman Singidunum". It is situated in the area that used to be the civilian sector of the city, outside the fortress. The remnants were visible until 1978 and due to the lack of funds to continue excavations or to cover it with the roof or a marquee, the remains were conserved and buried again.[3][4]

Great Market

At the place of the modern square, there was an open green marketplace for over a century. At the beginning of the 19th century, farmers were selling goods at the entrances to the city. However, Turkish soldiers would often forcibly buy goods from them at the small prices, and then sell it themselves in the city for much higher amounts. After constant complaints from the farmers, vizier of Belgrade, after counseling with the city merchants, agreed to choose one place for the market: da se učini u Beogradu jedno pazarište ili Toržište ("a bazar or a marketplace is to be founded in Belgrade").[5][6][7]

Also, in 1821, the state government decided to put the food trade in order and to establish the quantity and quality of the goods imported to the city. Part of the project was introduction of the excise on the goods (in Serbian called trošarina) and setting of a series of excise check points on the roads leading to the city. That same year, the city's first proper greenmarket became operational. Originally, it opened in 1824 right across the Belgrade Fortress, in the modern Pariska street, stretching between the Uzun Mirkova and Knez Mihailova streets, where the City Library is today. Only 4 days later, it was moved to the location above the old, defunct Turkish cemetery. The chosen location was situated above the Tekija building and the Kizlar Aga's Mosque, close to the starting section of the Tsarigrad Road. The market was soon equipped with market stalls for selling fruits and vegetables and barracks for the dairy products, eggs and dried meat. Raw meat was not allowed at the market. Poultry was sold alive and only in pairs. Other meat was prepared and sold in butcher shops and, since there were no refrigerators, had to be sold by noon. Apart from being the first arranged and planned market in the city, it also was the first to have a sanitary inspection which checked the hygiene, quality and freshness of the goods.[7][8][9]

As per Serbian-Turkish agreement anyone could bring and sell goods, the market quickly grew and became city’s commercial center. Though it was officially named "Saint Andrew's Market" it becamne known as the Great Market (Serbian: Velika pijaca or Veliki pijac).[5][7]

Formation of the square

The square developed around the market, also occupying parts of the former Turkish graveyard. It was originally called Veliki trg ("Great Square"). As the ceremony of proclamation of Serbia into the kingdom in 1882 was held here, the square was renamed to Kraljev trg ("King's Square").[7] In 1863 the Captain Miša's Mansion was built and the Great School moved in. In the direction of Kalemegdan, municipal administration of Belgrade was located and the building was later used for the municipal court. Later city administration building was also located here, just on the northern side. At the corner with the Zmaja od Noćaja Street, the fire brigade was situated. They used the lookout on the top of the Captain Miša's Mansion to inspect the city.[9] In the kafana Kod Rajića junaka serbskog, prince Mihajlo Obrenović organized festivities after he was handed over the keys to the city from the Ottomans, who had to evacuate the Belgrade Fortress.[10]

First modern Belgrade’s urbanist Emilijan Josimović suggested dislocation of the market in 1887, as it was placed in the sole center of the city. Plus, he deemed it inappropriate for the Great School to be across the market. But when the horse-drawn tram was introduced in Belgrade 1892, and it passed through this part of the city, the market actually bloomed even more. Josimović met with lots of resistance and only some time before his death, he managed for the city to decide to split the market in two and form a park in one of the sections. The open space area around the market, which was now a defunct Turkish cemetery, and the northwestern section were turned into the park. It was open on 11 May 1897, just two weeks before Josimović's death. On the same day, the monument to Josif Pančić, work of sculptor Đorđe Jovanović was erected in the park. As the monument was covered with cloth for a long time, citizens colloquially nicknamed the square a "plateau of the bagged man".[5][6][7][9]

The market itself continued to operate until 1926 when was finally closed. With the closing of the Great Market, city government built several other markets in the city, bit further from the downtown: Zeleni Venac, Kalenić market, Bajloni market and Jovanova market. The park that was created was named Pančićev Park, after his monument in the park, and is today known as the Akademski Park. Pančić's monument was coupled with the monument dedicated to Dositej Obradović in 1914, which was transferred to the Akadameski park in the early 1930s from his previous location at the end of the Knez Mihailova street.[5][6] The square was finally formed in its preset shape by 1927, with the park in the central part. Park was planned by architect Đorđe Kovaljski while the recognizable enclosure and the gates were added in 1929, on the project of Milutin Borisavljević.[9]

Characteristics

Studentski Trg was projected as the first in a succession of squares around Belgrade's central route from Kalemegdan to Slavija: Studentski Trg-Trg Republike-Terazije-Cvetni Trg-Slavija.

In time, Studentski Trg and Terazije pretty much lost their square functions, becoming streets, while Cvetni Trg, with final changes in early 2000s, is completely defunct as a traffic object. Studentski Trg is turned into the turning point and terminal station for bus line number 31 and majority of Belgrade's trolleybus lines (19, 21, 22, 22L, 28, 29 and 41).

Studentski Trg is location of many educational and cultural institutions, thus the names (Students Square, Academy Park, etc.). They include:

- Rectorate of the University of Belgrade in the representative Captain Miša's Mansion;

- Faculty for Natural Sciences and Mathematics ( University of Belgrade);

- University of Belgrade Faculty of Philosophy;

- University of Belgrade Faculty of Philology;

- Kolarac Public University, with concert hall

- Ethnographic museum

- A monument to Petar II Petrović Njegoš

Faculty of Philosophy Plateau

In the 19th century, before hotels in Belgrade were founded, numerous khans existed in the city. Oriental variant of the roadside inn, they provided travelers with food, drink and resting facilities. One of the largest in Belgrade at the time was the Turkish Khan (Turski han), located where the modern plateau is.[11]

In 1964 the request for tender for the new building of the Faculty of Philosophy on the location of the former hotel "Grand" was announced. As the several surrounding small houses were also demolished, one of the propositions was the wide space between the new faculty building and the Captain Miša's Mansion. Svetislav Ličina, only 34 at the time, won, despite many distinguished architects took part in the tendering. The work was finished in 1974. Ličina projected an elevated four-storeys connection between the new and the old building, leaving a wide open connection between the Studentski Trg and Knez Mihailova Street. That way, the small square, piazzetta, formed by the streets of Knez Mihailova and Čika Ljubina, with the drinking fountain, continued into the newly formed plateau on Studentski Trg.[12]

Future

In July 2016 city administration announced the complete reconstruction of Studentski Trg and its adaptation into the pedestrian zone, construction of the underground garage and erection of a monument to the assassinated prime minister Zoran Đinđić.[13] The project of the reconstruction was designed by Boris Podrecca, but it was met with almost universal criticism from the architects, urbanists and public alike.

Architects opposed the general redesign of the square which appears to be planned with the absolute liberty, as if there aren't any cultural, architectural, archaeological or legal limitations due to the protection of the area and that, as such, damages and violates the cultural-monumental protection of the square. Creation of one single, large pedestrian zone from the Republic Square to Kalemegdan and the ban of the traffic was deemed "not realistic".[14] The project was labeled as the pompous, undeveloped designing intervention based solely on the aesthetic principle and the superficial interpretation of projects seen elsewhere. Other descriptions include the total lack of cultural arguments, lack of ideas, spirit, style and other things which marks the culture and identity of Belgrade.[15]

Part of the criticism concerns the public and professional debate on the project, that is, almost complete lack of it. The process of the architectural design competition has been described as "we draw the project, without previous thorough analysis and propositions, we win the award and the realization begins!".[15]

Podrecca was directly criticized for some of his previous problematic projects (Maribor, Trieste, etc.) and his construction of the lifeless and soulless squares. Decision on the removal of the traffic was brought without any proper idea what to do with it and where to conduct it, in the manner of "sweeping it under the rug". The removal of traffic from this section of the city needs a systematic solution on a much wider city area but the city government didn't provide any. Apparently, by the propositions, author of the project had no obligation to take care of the traffic, so he didn't.[15] The position of Podrecca to decide what will be turned into the pedestrian zone instead of just projecting the square, and the city's decision to close for the traffic streets in downtown has been disputed.[16]

Construction of the two-level underground garage is also criticized.[17] As if there is no archaeological locality beneath the park, while the protruding Roman elements, visible on the Faculty of Philosophy Plateau, remain isolated. Handling of these two localities is described as the typical indifference towards the archaeological remains and lack of concern for the cultural heritage. Area of the modern square is the first among the most important urban zones of old Belgrade and is especially important as the locality of ancient Singidunum which developed along the Terazije ridge. The locality has not been properly explored, historically or archaeologically, and now all the Roman and later Byzantine remains will be permanently destroyed.[14] The area of the square was described as having the deepest "cultural and historical sedimentation" in the city and the original source of the urban culture of Belgrade.[15]

It was pointed out that Studentski Trg is one of such ambient spaces which is defined by the elements important for the collective memory. aesthetic, spiritual or emotional experience of the majority of the citizens. That way, such spaces, especially in large cities, have public importance and with preserving the deeper historical layers in time achieve a status of specific historical, social or cultural identity and character.[15] Despite all the criticism, deputy mayor Goran Vesić announced in September 2018 that the construction will start "in the fall".[18]

Monument to Zoran Đinđić

The look of the future monument to the assassinated prime minister was announced on 21 October 2017. A modernist installation, work of sculptor Mrđan Bajić and dramatist Biljana Srbljanović, represents a "bent arrow, broken in the middle, but then continued to unstoppably fly to the skies". The arrow will be accompanied by the sound installations, with the recorded voice of Đinđić.[19] The overwhelmingly negative reaction from the public and professionals resulted in a heated debate, which tackled not only architectural, cultural and visual sides of the project, but also the morality of the idea.

Location of the Đinđić monument, across the Njegoš monument, has been labeled as the politically opportune,[14] while the monument itself is described as "appearing poor and unsustainable."[15] The design competition was said to be a "missed opportunity" and the direction of the arrow as wrong, as it directs the pedestrians to the sky, instead to Europe, where Đinđić was leading Serbia. The installation was depicted as inferior compared to the classical Prince Mihailo Monument on the Republic Square and denied its symbolism as "Đinđić himself, as a personality, was a symbol of the future".[20] It was suggested that probably the better place for such installation would be the vicinity of the Building of the General Staff, demolished in 1999 NATO bombing of Serbia.[21] Author and artist Mileta Prodanović, on the other hand, liked the proposition.[22] Opposing voices also mentioned a fact that a monument, which represents a person or an event, in order to remain in the permanent memory, must associate on that person or an event. That passers-by and tourists can't have with them dictionary of symbols all the time. Also, was it a competition for a monument or an installation, in which case the jury missed the point.[23]

Association of the Serbian Architects (ASA) asked for the competition to be annulled, citing procedural reasons. They claim the jury digressed from the basic propositions. It includes the anonymity as Bajić directly collaborates with two jury members (Vladimir Veličković and Dušan Otašević), while he circled his cipher on the presented work, by which, they allege, he indicated to the jury that it was his work. The ASA also accused Podrecca of the conflict of interest. As a "financially interested party", being the author of the square reconstruction, he shouldn't serve as the jury president.[24]

References

- ↑ Tamara Marinković-Radošević (2007). Beograd - plan i vodič. Belgrade: Geokarta. ISBN 86-459-0006-8.

- ↑ Beograd - plan grada. Smedrevska Palanka: M@gic M@p. 2006. ISBN 86-83501-53-1.

- ↑ Branka Vasiljević (14 November 2011), "Počinje uređenje Akademskog parka", Politika (in Serbian)

- ↑ Branka Vasiljević (27 May 2009), "Rimske terme ispod Akademskog parka", Politika (in Serbian)

- 1 2 3 4 D.J.S. (13 December 2014), "Pijace slave Svetog Andreja Prvozvanog", Politika (in Serbian), p. 15

- 1 2 3 Dragan Perić (23 April 2017), "Šetnja pijacama i parkovima", Politika-Magazin No 1021 (in Serbian), pp. 28–29

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ana Vuković (25 May 2018). "Oživljava "Velika pijaca" na Studentskom trgu" ["Great Market" on Studentski Trg is coming back to life]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 14.

- ↑ Dragan Perić (22 October 2017), "Beogradski vremeplov - Pijace: mesto gde grad hrani selo" [Belgrade chronicles - Greenmarkets: a place where village feeds the city], Politika-Magazin, No. 1047 (in Serbian), pp. 26–27

- 1 2 3 4 Dragan Perić (20 May 2018). "Od pijace do Studentskog parka" [From green market to Student's park]. Politika-Magazin, No. 1077 (in Serbian). p. 29.

- ↑ Goran Vesić (14 September 2018). "Прва европска кафана - у Београду" [First European kafana - in Belgrade]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 12.

- ↑ Dragan Perić (2 September 2018). "Kada su svi putevi vodili u Beograd" [When all roads were leading to Belgrade]. Politika-Magazin, No. 1092 (in Serbian). pp. 28–29.

- ↑ Milorad H. Jevtić (18 January 2012), "Urbano pulsiranje platoa", Politika (in Serbian)

- ↑ "Ovako će izgledati Studentski trg" [This is how Studentski Trg will look like] (in Serbian). B92. 13 July 2016.

- 1 2 3 Miroljub Kojović (30 October 2017), "Istoriju Singidunuma prepuštamo zaboravu" [We leave he history of Singidunum to the oblivion], Politika (in Serbian)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Borislav Stojkov (4 November 2017), "Da li se građani za nešto pitaju" [Are citizens being asked about anything?], Politika-Kulturni dodatak (in Serbian), p. 07

- ↑ Sandra Petrušić (10 May 2018). "Темељна бетонизација – Напредњачка хуманизација града" [Thorough concreting - Progressive's humanization of the city]. NIN, No. 3515 (in Serbian).

- ↑ Aleksandra Pavićević (7 July 2018). "Нажалост, (пре)познајемо се" [Unfortunately, we know (recognize) us]. Politika-Kulturni dodatak, Year LXII, No. 13 (in Serbian). pp. 06–07.

- ↑ Dejan Aleksić (5 September 2018). "Majstori uskoro u Karađorđevoj i Marka Kraljevića" [Workers soon in the Karađorđeva and Marka Kraljevića streets]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 15.

- ↑ N1, Beoinfo (21 October 2017). "Izabrano idejno rešenje za spomenik Đinđiću u Beogradu" [The conceptual idea for the Đinđić monument in Belgrade has been selected] (in Serbian). N1.

- ↑ Aleksandar Rudnik Milanović (27 October 2017), "Skulptura, simbol i lokacija" [Sculpture, symbol and location], Politika (in Serbian)

- ↑ Miroljub Kojović (7 November 2017), "Još jedan apel za stari Beograd" [One more appeal for the old Belgrade], Politika (in Serbian), p. 27

- ↑ Mileta Prodanović (7 November 2017). "Dve greške Borisa Tadića" [Two errors of Boris Tadić] (in Serbian). Danas.

- ↑ Branislav Simonović (30 November 2017), "Spomenik i tumačenje" [A monument and an interpretation], Politika (in Serbian), pp. 24–25

- ↑ Miroslav Simeunović (7 December 2017), "Proceudralne manjakovsti konkursa za spomenik Đinđiću" [Procedural inadequacy of the competition fort the Đinđić's monument], Politika (in Serbian)