Autonomous Province of Kosovo and Metohija

| Autonomous Province of Kosovo and Metohija Аутономна Покрајина Косово и Метохиja Autonomna Pokrajina Kosovo i Metohija Krahina Autonome e Kosovës dhe Metohisë | |

|---|---|

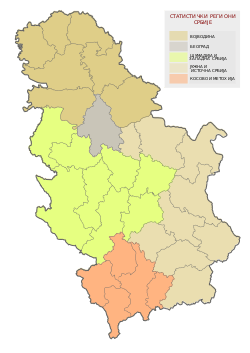

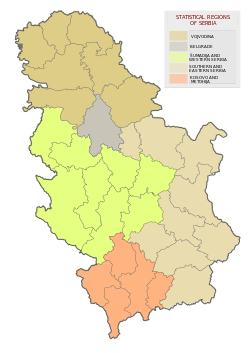

Map of Kosovo and Metohija within Serbia | |

| Status |

Autonomous province (UNSC 1244) |

| Capital and largest city |

Pristina 42°40′N 21°10′E / 42.667°N 21.167°E |

| Official languages | |

| Recognised regional languages | |

| Autonomy | |

• Formation of Serbia and Montenegro | 1992 |

| 1999 | |

| 2008 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 10,908 km2 (4,212 sq mi) |

• Water (%) | n/a |

| Population | |

• 2007 estimate | 1,804,838[Note 1] |

• 2011 census | 1,780,021 |

• Density | 220/km2 (569.8/sq mi) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2009 estimate |

• Total | $5.352 billion[3] |

• Per capita | $2,965 |

| Currency |

Euro (EUR) Serbian dinar (RSD) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| UTC+2 (CEST) | |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +383 |

| Internet TLD | .rs |

Kosovo and Metohija (Serbian: Косово и Метохија / Kosovo i Metohija (КиМ / KiM), Albanian: Kosova dhe Dukagjini), officially the Autonomous Province of Kosovo and Metohija (Serbian: Аутономна Покрајина Косово и Метохиja / Autonomna Pokrajina Kosovo i Metohija, Albanian: Krahina Autonome e Kosovës dhe Metohisë), known as short Kosovo (Serbian Cyrillic: Косово, Albanian: Kosova) or simply Kosmet (from Kosovo and Metohija; Serbian Cyrillic: Космет),[4] refers to the region of Kosovo[5] as defined in the Constitution of Serbia. The territory of the province is disputed between Serbia and the self-proclaimed Republic of Kosovo, the latter of which has de facto control. The region had functioned as part of Serbia (mainly while Serbia had been part of a Yugoslav state) for most of the period between 1912 and 1999.

The territory of the province, as recognized by Serbian laws, lies in the southern part of Serbia and covers the regions of Kosovo and Metohija. The capital of the province is Pristina. The territory was previously an autonomous province of Serbia during Socialist Yugoslavia (1946–1990), and acquired its current status in 1990. The province was governed as part of Serbia until the Kosovo War (1998–99), when it became United Nations (UN) protectorate in accordance with United Nations Security Council Resolution 1244, but still internationally recognized as part of Serbia. The control was then transferred to the UN administration of UNMIK. In 2008, Kosovo authorities unilaterally declared independence, which is recognized by 111 UN members, but not by Serbia which still regards it as its province.

Overview

In 1990, the Socialist Autonomous Province of Kosovo, an autonomous province of Serbia within Yugoslavia, had undergone the Anti-bureaucratic revolution by Slobodan Milošević's government which resulted in the reduction of its powers, effectively returning it to its constitutional status of 1971–74. The same year, its Albanian majority – as well as the Republic of Albania – supported the proclamation of an independent Republic of Kosova. Following the end of the Kosovo War 1999, and as a result of NATO intervention,[6][7] Serbia and the federal government no longer exercised de facto control over the territory.

In February 2008, the Republic of Kosovo declared independence.[8][9] While Serbia has not recognised Kosovo's independence, in the Brussels agreement of 2013, it abolished all its institutions in the Autonomous Province. Kosovo's independence has been recognised by 113 UN member states (with two withdrawals to date).[6][10] In 2013, the Serbian government announced it was dissolving the Serb minority assemblies it had created in northern Kosovo, in order to allow the integration of the Kosovo Serb minority into the general population of Kosovo.[11]

History

Constitutional changes were made in Yugoslavia in 1990. The parliaments of all Yugoslavian republics and provinces, which until then had MPs only from the League of Communists of Yugoslavia, were dissolved and multi-party elections were held within them. Kosovar Albanians refused to participate in the elections so they held their own unsanctioned elections instead. As election laws required (and still require) turnout higher than 50%, a parliament in Kosovo could not be established.

The new constitution abolished the individual provinces' official media, integrating them within the official media of Serbia while still retaining some programs in the Albanian language. The Albanian-language media in Kosovo were suppressed. Funding was withdrawn from state-owned media, including those in the Albanian language in Kosovo. The constitution made the creation of privately owned media possible, however their operation was very difficult because of high rents and restrictive laws. State-owned Albanian language television or radio was also banned from broadcasting from Kosovo.[12] However, privately owned Albanian media outlets appeared; of these, probably the most famous is "Koha Ditore", which was allowed to operate until late 1998 when it was closed after publishing a calendar glorifying ethnic Albanian separatists.

The constitution also transferred control over state-owned companies to the Yugoslav central government. In September 1990, up to 123,000 Albanian workers were dismissed from their positions in government and media, as were teachers, doctors, and civil servants,[13] provoking a general strike and mass unrest. Some of those who were not sacked quit in sympathy, refusing to work for the Serbian government. Although the sackings were widely seen as a purge of ethnic Albanians, the government maintained that it was removing former communist directors.

Albanian educational curriculum textbooks were withdrawn and replaced by new ones. The curriculum was (and still is, as this is the curriculum used for Albanians in Serbia outside Kosovo) identical to its Serbian counterpart and that of all other nationalities in Serbia except that it had education on and in the Albanian language. Education in Albanian was withdrawn in 1992 and re-established in 1994.[14] At the Priština University, which was seen as a centre of Kosovo Albanian cultural identity, education in the Albanian language was abolished and Albanian teachers were also dismissed in large numbers. Albanians responded by boycotting state schools and setting up an unofficial parallel system of Albanian-language education.[15]

Kosovo Albanians were outraged by what they saw as an attack on their rights. Following mass rioting and unrest from Albanians as well as outbreaks of inter-communal violence, in February 1990, a state of emergency was declared and the presence of the Yugoslav Army and police was significantly increased to quell the unrest.

Unsanctioned elections were held in 1992, which overwhelmingly elected Ibrahim Rugova as "president" of a self-declared Republic of Kosova; Serb authorities rejected the election results, and tried to capture and prosecute those who had voted.[16] In 1995, thousands of Serb refugees from Croatia were settled in Kosovo, which further worsened relations between the two communities.

Albanian opposition to the sovereignty of Yugoslavia and especially Serbia had previously surfaced in rioting (1968 and March 1981) in the capital Pristina. Rugova initially advocated non-violent resistance, but later opposition took the form of separatist agitation by opposition political groups and armed action from 1996 by the "Kosovo Liberation Army" (Ushtria Çlirimtare e Kosovës, or UÇK) whose activities led to the Kosovo War ending with the 1999 NATO bombing of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and the eventual creation of the UN Kosovo protectorate (UNMIK).

In 2003, the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia was renamed the State Union of Serbia and Montenegro (Montenegro left the federation in 2006 and recognised Kosovo's independence in 2008).[17]

Violent 2004 unrest in Kosovo broke out on 17 March 2004. Kosovo Albanians, numbering over 50,000, took part in wide-ranging attacks on the Kosovo Serb minority. It was the largest violent incident in Kosovo since the Kosovo War of 1998–1999. According to reports by news sources in Serbia, during the unrest, civilians were killed, thousands of Serbs were forced to leave their homes. In Serbia the events were also called the March Pogrom.

Politics and government

Since 1999, the Serb-inhabited areas of Kosovo have been governed as a de facto independent region from the Albanian-dominated government in Pristina. They continue to use Serbian national symbols and participate in Serbian national elections, which are boycotted in the rest of Kosovo; in turn, they boycott Kosovo's elections. The municipalities of Leposavić, Zvečan and Zubin Potok are run by local Serbs, while the Kosovska Mitrovica municipality had rival Serbian and Albanian governments until a compromise was agreed in November 2002.[18]

The Serb areas have united into a community, the Union of Serbian Districts and District Units of Kosovo and Metohija established in February 2003 by Serbian delegates meeting in Kosovska Mitrovica, which has since served as the de facto "capital." The Union's president is Dragan Velić. There is also a central governing body, the Serbian National Council for Kosovo and Metohija (SNV). The President of SNV in North Kosovo is Dr Milan Ivanović, while the head of its Executive Council is Rada Trajković.[19]

Local politics are dominated by the Serbian List for Kosovo and Metohija. The Serbian List was led by Oliver Ivanović, an engineer from Kosovska Mitrovica.[20]

In February 2007 the Union of Serbian Districts and District Units of Kosovo and Metohija has transformed into the Serbian Assembly of Kosovo and Metohija presided by Marko Jakšić. The Assembly strongly criticised the secessionist movements of the Albanian-dominated PISG Assembly of Kosovo and demanded unity of the Serb people in Kosovo, boycott of EULEX and announced massive protests in support of Serbia's sovereignty over Kosovo. On 18 February 2008, day after Kosovo's unilateral declaration of independence, the Assembly declared it "null and void".[21][22]

Also, there was a Ministry for Kosovo and Metohija within the Serbian government, with Goran Bogdanović as Minister for Kosovo and Metohija. In 2012, that ministry was downgraded to the Office for Kosovo, with Aleksandar Vulin as the head of the new office.[23] However, in 2013, Aleksandar Vulin post was raised into being a Minister without portfolio in charge of Kosovo and Metohija.

Administrative divisions

Five Serbian Districts are in the territory of Kosovo, comprising 28 municipalities and 1 city. In 2000, UNMIK created 7 new districts and 30 municipalities. Serbia does not exercise sovereignty over this polity. For the UNMIK districts and the districts of Kosovo, see Districts of Kosovo.

| District | Seat | Population in 2016 (rank) | Municipalities and cities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kosovo District (Kosovski okrug) |

Pristina | 672,292 | |

| Kosovo-Pomoravlje District (Kosovsko-Pomoravski okrug) |

Gnjilane | 166,212 | |

| Kosovska Mitrovica District (Kosovskomitrovički okrug) |

Kosovska Mitrovica | 225,212 | |

| Peć District (Pećki okrug) |

Peć | 178,326 | |

| Prizren District (Prizrenski okrug) |

Prizren | 376,085 |

See also

Notes

- ↑ Kosovo’s population estimates range from 1.9 to 2.4 million. The last two population censuses conducted in 1981 and 1991 estimated Kosovo’s population at 1.6 and 1.9 million respectively, but the 1991 census probably under-counted Albanians. The latest estimate in 2001 by OSCE puts the number at 2.4 million.[1] The World Factbook gives an estimate of 1,847,708 for July 2013.[2]

References

- ↑ Kosovo Population

- ↑ "Kosovo". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

- ↑ "Kosovo". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 2010-04-21.

- ↑ Heike Krieger (12 July 2001). The Kosovo Conflict and International Law: An Analytical Documentation 1974-1999. Cambridge University Press. pp. 282–. ISBN 978-0-521-80071-6.

- ↑ "Šta donosi predlog novog ustava Srbije" (in Serbian). 30 September 2006.

- 1 2 "NATO – Topic: NATO's role in Kosovo". Nato.int. 31 August 2012.

- ↑ Steven Beardsley. "Kosovo aims to form military force and join NATO – News". Stripes.

- ↑ "Kosovo's declaration of independence did not violate international law – UN court". UN News Centre. 22 July 2010. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- ↑ "ICJ,International Court of Justice:Declaration of independence of Kosovo from Serbia is not a violation of international law". Bbc newsamerica.com. Retrieved 2 January 2011.

- ↑ Steven Beardsley. "Kosovo aims to form military force and join NATO – News". Stripes. Retrieved 2013-08-18.

- ↑ Serbia Pulls Plug on North Kosovo Assemblies

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 8 June 2006. Retrieved 2006-06-09.

- ↑ ON THE RECORD: //Civil Society in Kosovo// - Volume 9, Issue 1 - August 30, 1999 - THE BIRTH AND REBIRTH OF CIVIL SOCIETY IN KOSOVO - PART ONE: REPRESSION AND RESISTANCE

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 11 April 2005. Retrieved 2006-06-09.

- ↑ Clark, Howard. Civil Resistance in Kosovo. London: Pluto Press, 2000. ISBN 0-7453-1569-0

- ↑ Noel Malcolm, A Short History of Kosovo, p.347

- ↑ Lonely Planet Montenegro. Lonely Planet. 2009. p. 15. ISBN 9781741794403.

- ↑ Day, Matthew (11 November 2010). "Serbia calls for boycott of Kosovo elections". The Daily Telegraph.

- ↑ Declaration of Establishing the Assembly of the Community of Municipalities of the Autonomous Province of Kosovo and Metohija (in English)

- ↑ "Ivanović: Frustracija Kosovom uzrok nestabilnosti". Blic.rs. Retrieved 2013-08-18.

- ↑ Vesna Peric Zimonjic (29 June 2008). "Kosovo Serbs set up rival assembly". The Independent. UK. Archived from the original on 30 June 2008. Retrieved 2008-06-29.

- ↑ Ben Cahoon. "Kosovo". Worldstatesmen.org. Retrieved 2011-03-31.

- ↑ "Closure of Serbian ministry sparks debate". Southeast European Times. 14 August 2012.