Kragujevac

| Kragujevac Крагујевац | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| City | |||

| City of Kragujevac | |||

Kragujevac photomontage | |||

| |||

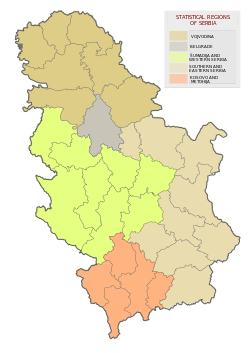

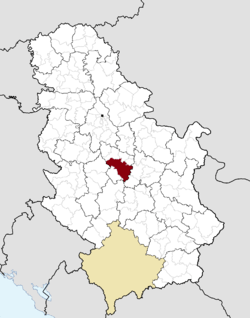

Location of the city of Kragujevac within Serbia | |||

| Coordinates: 44°00′40″N 20°54′40″E / 44.01111°N 20.91111°ECoordinates: 44°00′40″N 20°54′40″E / 44.01111°N 20.91111°E | |||

| Country |

| ||

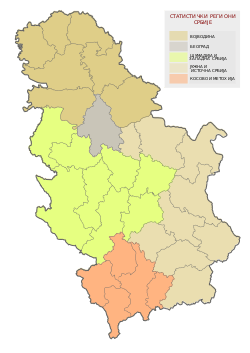

| Region | Šumadija and Western Serbia | ||

| District | Šumadija | ||

| Founded | 1476 | ||

| Government | |||

| • Mayor | Radomir Nikolić (SNS) | ||

| Area[1] | |||

| Area rank | 22nd in Serbia | ||

| • Urban | 82.83 km2 (31.98 sq mi) | ||

| • Administrative | 835 km2 (322 sq mi) | ||

| Elevation | 173 m (568 ft) | ||

| Population (2011 census)[2] | |||

| • Rank | 4th in Serbia | ||

| • Urban | 150,835 | ||

| • Urban density | 1,800/km2 (4,700/sq mi) | ||

| • Administrative | 179,417 | ||

| • Administrative density | 210/km2 (560/sq mi) | ||

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) | ||

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) | ||

| Postal code | СРБ-34 000 | ||

| Area code(s) | +381 34 | ||

| ISO 3166 code | SRB | ||

| Licence plates | KG | ||

| Website |

www | ||

Kragujevac (Serbian Cyrillic: Крагујевац, pronounced [krǎɡujeʋats] (![]()

Kragujevac was the first capital of modern Serbia (1818–1841); the first constitution in the Balkans was proclaimed in the city in 1835. The city's first grammar school and printworks were both established in 1833, followed by the professional National theatre (1835), Military academy (1837) and the first full-fledged university in the newly independent Serbia (1838). Kragujevac was the site of a massacre by the Nazis (1941), in which 2,778 Serb men and boys were murdered. Contemporary Kragujevac is known for its munitions (Zastava Arms) and automobile industry (Fiat Automobili Srbija).

As an important university center, the University of Kragujevac was established on 21 May 1976, from departments of the University of Belgrade Faculty of Mechanical Engineering and Faculty of Economics, which began to work in late 1960s. The University of Kragujevac includes twelve schools, six located in Kragujevac with others located in Čačak, Kraljevo, Jagodina, Užice and Vrnjačka Banja. The city has two scientific research institutes: the Institute for Field Crops in Kragujevac and Fruit and Grape Research Institute in Čačak.

The name Kragujevac derives from the archaic Serbian word "kraguj", describing a particular species of hawk. Thus, Kragujevac means "hawk's nesting place".[3]

History

Early and medieval

Kragujevac has experienced significant historical turbulence, often with severe casualties. Over 200 archaeological sites in Šumadija confirm that the region's first human settlements occurred 40,000 years ago, during the Paleolithic era. The "Jerina Cave", located near the village of Gradac in the direction of Batočina, was inhabited from 37,000 to 27,000 BP. The dugouts and the first constructions above the ground were built in 5,500-4,800 BC in the surrounding villages of Grivac, Kusovac, Divostin, Donje Grbice and Dobrovodica.[4]

Before the arrival of the Slavs, the territory of present city was inhabited by the Illyrians, Celts and Romans. Illyrian tribe of Dardani and Celtic tribe of Scordisci occupied the region, before the area was conquered by the Roman Empire in 9 AD.[4] This territory was captured from Byzantium by Stefan Nemanja in 1198-99, who consolidated the Serbian state in the twelfth century. In the Middle Ages, the area of modern Kragujevac was part of several Serbian states. Kragujevac was first mentioned in the medieval period as related to the public square built in a settlement, while the first written mention of the city was in the Ottoman Tapu-Defter of Smederevo in 1476.[4][5]

Ottoman documents from the 15th century refer to it as a "village of Kragujevdza". In 1536 census, Ottoman authorities name that Kragujevac kasaba (town in Turkish) has 7 Muslim mahalas with 56 houses in total, and a Christian community, jamia, with 29 houses. The town itself gained prominence during the Ottoman period (1459–1804) as the central point in the Belgrade Pashaluk (Sanjak of Smederevo).[4][6]

Kragujevac was shortly occupied by the Austrian army in 1689, when it was conquered by Louis of Baden. In 1718–39, the town was again controlled by the Habsburg Monarchy and was part of the Habsburg Kingdom of Serbia, this time taken by Prince Eugene of Savoy. In 1788, it was part of Kočina Krajina, an area controlled by the Serb rebels, while in 1789–90 it was again controlled by the Habsburg Monarchy.[4][7]

Early modern period

The city has been devastated many times and has suffered great losses of life in a number of wars throughout history. Kragujevac was liberated from the Ottomans on 5 April 1804, during the First Serbian Uprising. It began to prosper after the factual Serbia's liberation from Turkish rule in 1815, especially when Prince Miloš Obrenović proclaimed it the capital of the new Serbian State on 6 May 1818 during the May Assembly in the Vraćevšnica monastery. To mark the occasion, he then built the Amidža Konak.[8] The first Serbian constitution was proclaimed here on 15 September 1835 and the first idea of independent electoral democracy.[4]

The first law on the printing press was passed in Kragujevac in 1870. Kragujevac, the capital, was developing and cherishing modern, progressive, free ideas and resembled many European capitals of that time.[9]

The complex of the old foundry, which expanded in time, is called Vojnotehnički zavod u Kragujevcu or VTZ ("Military and technical institute in Kragujevac"). Colloquially styled "Prince's arsenal" (Knežev arsenal), it originates from 1836, when Prince Miloš ordered construction of the first military plants. In 1850 the government established an entire complex of the military factories. First director was Charles Loubry, a French engineer who was especially authorized to take over this duty in 1853 by the Emperor of France, Napoleon III.[10]

VTZ is the jumping-off place of the entire Serbian industry in an effort to distance Serbia from the Ottoman heritage and bring it closer to the Western Europe, the most important industrial heritage of Serbia and the unique complex in Southeast Europe. As only workers were allowed to enter the complex for decades, the citizens of Kragujevac called it the "Forbidden City" (Zabranjeni grad). The city purchased 4 ha (9.9 acres) of the complex in 2005, which marked the beginning of the opening of the Lepenica's right bank for the civilians. In March 2014, the entire complex, covering 52.8 ha (130 acres), was placed under the state protection.[10] As of 2017, the complex consists of 151 individual objects, of which 31 are protected as the unique heritage: old foundry, machine workshop, chimney, fire lookout tower, railway bridge over the Lepenica river, cartridge factory.[10]

Apart from contemporary political influence, Kragujevac became the cultural and educational center of Serbia. Important institutions built during that time include Serbia's first secondary school (Gimnazija), first pharmacy, and first printing press.[11]

The turning point in the overall development of Kragujevac was in 1851 when the Cannon Foundry began production, beginning a new era in the city's economic development. The first telephone exchange was installed in 1858 and in 1868 the first industrial brewery was opened by Nikola Mesarović.[4] The main industry of the 19th and 20th century was military production. The city became one of Serbia's largest exporters in 1886, when the main Belgrade–Niš railway connected through Kragujevac.[4]

The first workers' demonstrations, Crveni barjak ("Red flag"), were held on 27 February 1876. In 1878, the National Assembly of Serbia, seated in Kragujevac, accepted the stipulations of the Berlin Congress by which Serbia was officially recognized as an independent state. The Šumadija Division Oblast of the Serbian army, seated in Kragujevac, was formed in 1883.[4]

In 1891, the first regulatory urban plan for the town of Kragujevac was drafted and in the same year, the Higher Girl School was opened. In 1894, the first surgery section within the District Hospital was formed. The Upper (or Great) Park was finished in 1898 and the first cinema became operational in 1909 in the "Talpara" kafana.[4]

During World War I, Kragujevac again became the capital of Serbia (1914–1915), and the seat of many state institutions; even the Supreme Army Command was housed within the court house building.[4][12]

During the war, Kragujevac lost 15% of its population. On the night of 2 June 1918, a group of occupying Slovak soldiers from the Austro-Hungarian 71st infantry regiment mutinied in the city center. The soldiers, led by Viktor Kolibik, had recently returned from captivity in Russia and were to be immediately deployed to the Italian Front. The mutiny failed and 44 mutineers were executed.[13]

Interbellum period

The first cultural event in liberated Kragujevac occurred in 1918, which was the establishment of the Theater Gundulic; it lasted only one season and moved to Belgrade.[14] The Communists won the local elections in 1920, as they did in Belgrade. In 1935, the first bus line Kragujevac-Belgrade was established.[4] Following the model of Academic Theater in Belgrade, the Kragujevac Scholars Academic Theater was founded in 1924. It was a theater that supported contemporary ideas, modern approach to stage, live word and repertoire, thus gaining the reputation of a serious art organization.[15]

World War II

Kragujevac underwent a number of ordeals during World War II, the worst probably having been the Kragujevac massacre between 19 and 21 October 1941, in which nearly 2,800 men and boys were killed.[16][17] The shootings were conducted in retaliation for a joint Partisan-Chetnik attack on German soldiers. Fifty people were to be shot for every German soldier wounded and 100 for every German soldier killed. Among the dead was a class of pupils from the city's First Grammar School. A monument for the executed pupils is a symbol of the city.[18] This atrocity inspired a poem titled Krvava Bajka (A Bloody Fairy Tale) by Desanka Maksimović.[19] The site of the shootings was turned into a memorial park in 1953, which covers an area of 352 hectares. At the entrance to the memorial park, a monumental museum "21st October" dedicated to the victims was built in 1976.[20] The city was liberated from Germans on 21 October 1944.[4]

Post-war city

In the post-war period, Kragujevac developed more industry. Its main exports were passenger cars, trucks and industrial vehicles, hunting arms, industrial chains, leather, and textiles. The biggest industry, and the city's main employer was Zastava, which employed tens of thousands people.[21]

The first product of the Zastava Automobiles car company, the FIAT 750, was manufactured in 1955 under license to Fiat Automobiles (now FCA). In the following three decades, more than five million passenger cars (FIAT 750, Zastava 1300, Zastava 101, Zastava 128, Zastava Jugo, Jugo Florida, Fiat 500L))have been manufactured and marketed in 74 countries worldwide.[22]

The city industry suffered under United Nations economic sanctions during the Milošević era, and some parts reduced to rubble by the 1999 NATO bombing campaign.[23]

Future

In 2010 city signed a memorandum with the German development agency GIZ and in 2012 city hall adopted the strategy of urban development of the central city zone to 2030. Both documents were used as the basis for the detailed regulatory plan for the former military complex, VTZ, protected by the state. The plan, zaled "Zone 1" was endorsed by the city hall in December 2017 and covers 36.7 ha (91 acres), or 70% of the protected area, and consists of 4 sections: Zastava, Milošev venac, Vojnotehnički zavod and Pirotehnika. The project, which will be conducted in the next 20 years, is a realization of the decades-old aspirations of the city to spread over its central section onto the right bank of the Lepenica river. By December 2017, many objects within the complex deteriorated and the right bank of the Lepenica was urbanistically neglected. The authenticity and representative values of the complex must be preserved, but where it is allowed, the industrial and workers quarters will be transformed into the residential and commercial areas, traffic corridors and used for the numerous educational and cultural institutions.[10]

Geography and infrastructure

Kragujevac lies 180 metres (591 feet) above sea level. The coordinates of Kragujevac are 44°00'40 of northern latitude and 20°54'40 of eastern longitude. It is located in the valley of the river Lepenica. The city covers an area of 835 square kilometres (322 sq mi), surrounded with slopes of mountains Rudnik, Crni Vrh and Gledić mountains. Kragujevac is administrative center of Šumadija, region characterized by hilly – mountainous land.

Kragujevac is center of Šumadija region

Kragujevac is center of Šumadija region National Reserve Veliki Sturac, Mountain Rudnik

National Reserve Veliki Sturac, Mountain Rudnik

Cityscape

The architecture of Kragujevac displays a fusion of two different styles—traditional Turkish (nowadays almost completely gone) and 19th century Vienna Secession style.[24]

Modern conceptions also appear throughout the city, firstly in the shape of post-war concrete (usually apartments designed to house those left homeless during World War II), and secondly the up-to-date glass offices reflecting the ambitious business aspects of modern architects. Some important buildings in Kragujevac include:

- The old church of Descent of the Holy Spirit was built in 1818, as a part of Prince Miloš' court. Its interior was decorated from 1818 to 1822. The new belfry was built in 1907.

- The Old Parliament was built in the court of the church where the first parliamentary meeting was held in 1859. Many events of great historical importance, such as verifying the Berlin Congress decision about the independence of Serbia, took place there. After undergoing reconstruction in 1992, the building was converted into a museum.

- The Amidža Konak was built by Prince Miloš in 1820 as a residential house. It is one of the finest examples of regional architecture in Serbia. It now houses an exhibition from the National Museum.

- The Prince Mihailo Konak was built in 1860. Its architecture blends local tradition with European architectural concepts. The building is now the National Museum.

- The High School (Gimnazija) was built between 1885–87 according to designs from the Ministry of Civil Engineering. It is one of the city's oldest edifices designed in a European style, in the tradition of the oldest Serbian Gimnazija from 1833. Such famous Serbian scientists, artists and politicians as Svetozar Marković, Nikola Pašić, and Vojvoda Radomir Putnik, were educated in this school.

The Upper (Great) Park is the greatest park in Kragujevac. It was established in 1898. It is covered with more than 10 hectares (25 acres) of greeenery, and a dense canopy of century-old trees, renovated walkways and benches are the right place for rest, walk and relaxation. In the park and its immediate vicinity there are sports facilities for basketball, football, volleyball, tennis, as well as indoor and outdoor swimming pools. Lower (Small) Park is located in the city center, within the Milos Wreath complex. At its center there is a monument to the Fallen People of Šumadija. The Ilina Voda park, a legacy of Svetozar Andrejević, was established in 1900. It covers an area of 7 hectares (17 acres).

There is a fountain with a small waterfall, five mini lakes connected by a small stream, and a small zoo with about 100 animals and a garden with various types of trees characteristic of Šumadija. The curiosity in the park is the largest sculpture of Easter eggs (3 metres (10 ft) high) in Europe and the second in the world; made from recycled metal, set in 2004.[25] Scenic attractions nearby include the Aranđelovac, Gornji Milanovac, Vrnjačka Banja, and Mataruška Banja, Karađorđe's castle, the Church of Saint George in Topola 40 kilometres (25 miles) away, the Old Kalenić monastery 55 kilometres (34 miles) away, the resorts of Rogot (28 km (17 mi)) and Stragari (34 km (21 mi)) with the old Blagoveštenje and Voljavča monasteries.

- View of Kragujevac

Kragujevac Cathedral

Kragujevac Cathedral Pedestrian zone

Pedestrian zone Amidžin Konak

Amidžin Konak

Transportation

Kragujevac has developed transportation infrastructure. It can be reached by five important roadways from: a) Belgrade, via Batocina, by State road (clas 1b) number 15; b) the Montenegrin border, via Novi Pazar and Kraljevo, by State road (clas 1b) number 15; c) Belgrade, via Mladenovac and Topola, by State road (clas 1b) number 16; d) Jagodina, via Donja Sabanta, by State road (class 2) number 170; e) Gornji Milanovac, via Bare, by State road (class 2) number 176.[26]

Kragujevac is connected by bus lines with almost all cities in the country. The most frequent departures (every half-hour) are to Belgrade. The central bus station is about a kilometer away from the city center. Kragujevac can also be reached by train, although the city is located outside the main railway lines. The central train Station is located close to the central bus station.[27]

Company responsible for public transportation in Kragujevac is City Traffic Agency. The integrated public transport is performed by three companies: Lasta, Arriva Litas and Vulovic Transport. There are 25 bus lines operating according to established timetable.[28] There are also 7 Taxi and 3 rent-a-car companies operating in Kragujevac.[29] Car parking system with 10 parking lots and zoned street parking (three zones with 4,244 parking spaces) is operated by public service company Parking Service Kragujevac.[30]

Climate

Kragujevac has an oceanic climate (Köppen climate classification: Cfb), and with a July mean temperature of 21.9 °C (71.4 °F), falling only 0.1 °C short of a humid subtropical climate (Köppen climate classification: Cfa). Winds most often blow from southwest and northwest, while they often blow from Southeast in January, February and March.[31]

| Climate data for Kragujevac (1981–2010, extremes 1961–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 20.6 (69.1) |

24.2 (75.6) |

29.4 (84.9) |

31.4 (88.5) |

35.4 (95.7) |

39.4 (102.9) |

43.9 (111) |

40.4 (104.7) |

37.4 (99.3) |

32.6 (90.7) |

27.6 (81.7) |

21.0 (69.8) |

43.9 (111) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 5.2 (41.4) |

7.3 (45.1) |

12.5 (54.5) |

17.8 (64) |

23.0 (73.4) |

26.1 (79) |

28.7 (83.7) |

28.8 (83.8) |

24.0 (75.2) |

18.5 (65.3) |

11.6 (52.9) |

6.2 (43.2) |

17.5 (63.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 0.9 (33.6) |

2.3 (36.1) |

6.6 (43.9) |

11.7 (53.1) |

16.7 (62.1) |

20.0 (68) |

21.9 (71.4) |

21.5 (70.7) |

16.9 (62.4) |

11.9 (53.4) |

6.4 (43.5) |

2.1 (35.8) |

11.6 (52.9) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −2.6 (27.3) |

−1.9 (28.6) |

1.8 (35.2) |

5.9 (42.6) |

10.6 (51.1) |

13.8 (56.8) |

15.3 (59.5) |

15.1 (59.2) |

11.3 (52.3) |

7.1 (44.8) |

2.5 (36.5) |

−1.1 (30) |

6.5 (43.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −27.6 (−17.7) |

−23.8 (−10.8) |

−18.3 (−0.9) |

−5.8 (21.6) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

2.7 (36.9) |

7.2 (45) |

4.6 (40.3) |

−2.2 (28) |

−6.6 (20.1) |

−16.4 (2.5) |

−20.7 (−5.3) |

−27.6 (−17.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 37.9 (1.492) |

37.0 (1.457) |

42.3 (1.665) |

53.9 (2.122) |

58.7 (2.311) |

76.4 (3.008) |

57.7 (2.272) |

58.6 (2.307) |

51.6 (2.031) |

48.9 (1.925) |

49.5 (1.949) |

45.8 (1.803) |

618.5 (24.35) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 12 | 12 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 12 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 13 | 132 |

| Average snowy days | 8 | 7 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 7 | 29 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 79 | 75 | 69 | 67 | 68 | 68 | 65 | 67 | 72 | 75 | 77 | 81 | 72 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 71.9 | 94.8 | 144.5 | 180.4 | 234.5 | 257.4 | 293.5 | 275.5 | 200.8 | 152.1 | 93.9 | 63.7 | 2,078.1 |

| Source: Republic Hydrometeorological Service of Serbia[32] | |||||||||||||

Municipalities and settlements

- Defunct city municipalities

From May 2002 until March 2008, the city of Kragujevac was divided into the following city municipalities:

- Settlements

List of settlements in the city of Kragujevac:

|

|

Demographics

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

| 1948 | 85,468 | — |

| 1953 | 93,465 | +1.80% |

| 1961 | 105,711 | +1.55% |

| 1971 | 130,551 | +2.13% |

| 1981 | 164,823 | +2.36% |

| 1991 | 180,084 | +0.89% |

| 2002 | 175,802 | −0.22% |

| 2011 | 179,417 | +0.23% |

| Source: [33] | ||

According to the 2011 census results, the city administrative area has a population of 179,417 inhabitants.

Around 70% (126,312 inhabitants) is of working age (aged 15 to 64). Average number of employees in 2014 was 42,148 (47.0% of women), most of who worked in metalworking industry (22%) and medical and social services (13%). Majority of persons aged more than 15 (154,290) have secondary education (54.6%), while 17.7%% hold a college or university degree.[34]

Around 93% of total city area is covered with water supply system, 78% with sewage system, 72% with natural gas supply network, and 92% with cell phone networks.[35]

Ethnic groups

| Ethnic group | Population 2011[36] |

|---|---|

| Serbs | 172,052 |

| Romani | 1,482 |

| Montenegrins | 645 |

| Macedonians | 297 |

| Croats | 192 |

| Yugoslavs | 175 |

| Gorani | 101 |

| Muslims | 97 |

| Others | 4,376 |

| Total | 179,417 |

Politics

Results of the 2012 local elections (there are 87 seats in local assembly) are the following:[37]

Economy

Kragujevac has been an important industrial and trading center of Serbia for more than two centuries, known for its automotive and firearms industries. The former state-owned Zastava Automobiles company was purchased by Fiat in 2008, and new company was established - FCA Srbija. Fiat was joined by partners Magneti Marelli (exhaust systems and control panels), Johnson Controls (car seats and interiors), Sigit (thermoplastic and rubber components) and HTL (wheels).

Weapons manufacturing in Kragujevac began with foundation of Kragujevac Cannon Foundry in 1853 and has since grown to become Serbia's primary supplier of firearms through the Zastava Arms corporation.[38] Today, Zastava Arms exports more than 95% of its products to over forty countries in the world. By the decisions of the Ministry of Defence of Serbia, Zastava Arms became a part of the Defense Industry of Serbia in 2003. The most important partners of Zastava Arms are Yugoimport SDPR, Army and Police of Serbia, Century Arms, and International Golden Group.

Rapp Marine Group (components for ships, oil platforms and machines), Meggle AG (dairy products), Unior Components (broaches, welded construction, thermal treatment), Metro Cash and Carry, Mercator and Plaza Centers (retail) established their operations in Kragujevac. The most important local companies include Forma Ideale, Blažeks (furniture), KUČ Company (dairy products), Jagger and Valentino (fashion production), Prizma (medical equipment production and distribution), Agromarket (trade of raw materials for agriculture), Budućnost (meat industry), Agrojevtic (production of bread and pastry), Flores (brandy), and Trnava Promet (retail).

According to National Bank of Serbia, there were 30 commercial banks operating in Serbia as of December 2016,[39] of which Direktna Banka has its headquarters in Kragujevac. Direktna banka has had a long tradition of operating in Central Serbia dating back to the second half of the 21st century.[40]

The Kragujevac Fair was established in 2005 thanks to the project "Support to the development and promotion of regional economy through development of City Fair". It comprises 1,600 square metres (17,222 sq ft) of area dedicated to trade and exhibitions and 1,000 square metres (10,764 sq ft) of area for other activities (administration, Media center, restaurant etc.).[41]

The following table gives a preview of total number of employed people per their core activity (as of 2016):[42]

| Activity | Total |

|---|---|

| Agriculture, forestry and fishing | 119 |

| Mining | 10 |

| Processing industry | 13,746 |

| Distribution of power, gas and water | 1,031 |

| Distribution of water and water waste management | 783 |

| Construction | 1,831 |

| Wholesale and retail, repair | 7,501 |

| Traffic, storage and communication | 2,199 |

| Hotels and restaurants | 1,652 |

| Media and telecommunications | 1,144 |

| Finance and insurance | 1,074 |

| Property stock and charter | 143 |

| Professional, scientific, innovative and technical activities | 1,802 |

| Administrative and other services | 1,755 |

| Administration and social assurance | 2,702 |

| Education | 4,202 |

| Healthcare and social work | 4,959 |

| Art, leisure and recreation | 889 |

| Other services | 1,016 |

| Total | 48,560 |

Society and culture

Education

There are 22 primary and 8 secondary schools in Kragujevac.[43] There are also 3 special schools: School for hearing impaired children,[44] Music school Dr Miloje Milojevic,[45] and the Vukasin Markovic School (for children with disabilities).[46]

The University of Kragujevac was established on 21 May 1976 although the first higher education institutions started with operations in 1960 as departments of the University of Belgrade. It is fourth largest university in Serbia and is organized in 12 faculties and two institutes which are spread over six cities (Kragujevac, Čačak, Kraljevo, Užice, Jagodina and Vrnjačka Banja) of the Central Serbia region which covers an area populated by 2,500,000 people. Around 16,000 students is currently enrolled at the university. It has around 1,350 employees out of which 900 is teaching and research staff.[47]

The University Library in Kragujevac is of generally scientific character, and its primary users are university teaching staff and students. Its area is 1,500 square metres (16,000 square feet) and includes several storage rooms, reading area and University Gallery. The library takes care of around 100,000 copies of books, 2,500 doctoral and master thesis, 450 titles of domestic journals and 105 titles of foreign journals.[48]

Culture

There are many cultural institutions in Kragujevac that have gained regional, and some of them even national significance in the field of arts and culture. The most important of these institutions are:

- Knjaževsko-srpski teatar (founded in 1835),

- National Library "Vuk Karadžić" (1866),

- Cultural and Artistic Group "Abrasević" (1904).

- The "Kragujevac October" Memorial Park, located in Šumarice, commemorates the tragic events of 21 October 1941.

- The National Museum has various displays including those pertaining to archeology, ethnic diversity, the history of Kragujevac and Šumadija and many paintings. The archeology department has a rich collection of 10,000 display items and over 100,000 study items. The painting department has over 1,000 pieces of prominent Serbian art of extraordinary value.[49]

- The "Old Foundry Museum" is located within the old gun foundry, the oldest surviving part of the military factory with military – artisan school, the first of its kind in the principality of Serbia. Museum is founded in 1953 and exhibits the history of industrial development in Kragujevac and Serbia. It has the collection of 5,800 pieces: weapons and equipment, machines and tools, archive material, photos, paintings, trophies and medals.[50]

- The Historical Archives of Šumadija collects and files the archives and issues of the seven municipalities of Šumadija and has at its disposal 700 metres (2,297 feet) of archive issues with 780 registries and hundreds of thousands of original historical documents.

There are three fine and applied arts associations in Kragujevac: the Art KG, the branch of the Serbian Association of Painters ULUS and the Association of Painters of Kragujevac (ULUK). The most important annual and biannual cultural events include:

- International Festival of Chamber Choir Music

- International Festival of Chamber Music

- The Best Serbian Theatrical Performances Festival

- International Small Forms Theatre Festival

- "Arsenal Fest" (a music festival)

- International Saloon of Antiwar Cartoons

- International Art Workshop "Balkan Bridges"

- International Jazz Festival

- International Puppet Theatre Festival

Sports

Kragujevac is home to Čika Dača Stadium, which is the third largest stadium in Serbia by seat capacity. The largest and most important sports association in Kragujevac is Radnički, which brings together 19 clubs: football, athletics, volleyball, handball, boxing, wrestling etc. FK Radnički 1923 is the city's most successful football club and competes in the Serbian SuperLiga. Kragujevac is also known for having the oldest Serbian football club FK Šumadija 1903. It should be noted that FK Bačka 1901 is the oldest club in present-day Serbia. FK Bačka 1901 was founded in Subotica, which at the time was located in Austro-Hungary, while Kragujevac was in Serbia. Therefore, Šumadija is considered the oldest Serbian football club, while Bačka is the oldest football club in Serbia.[51]

KK Radnički is the city's premier basketball team which. Besides the Basketball League of Serbia it also competes in the Adriatic Basketball League. Volleyball club Radnički is one of strongest volleyball teams in Serbia, and water polo club VK Radnički Kragujevac competes in the Serbian Water polo League A and has won the domestic league and the LEN Trophy in 2013. The city is home to the CROSS OVER Basketball Summer Camp, and Bandy Federation of Serbia.[52] The team of Kragujevac plays against the one from Subotica.

Faculty of Economics of the University in Kragujevac is founder of the futsal club KMF Ekonomac. The club was founded by Professor Veroljub Dugalić, several teaching assistants and a group of Faculty of Economics students on 7 November 2000. The club is playing in the Prva Futsal Liga and has won the Serbian championship eight times and Serbian Futsal Cup twice.

Local media

|

Radio stations

|

TV stations |

Newspapers |

Gallery

Description Monument to slain people from Šumadija in the wars

Description Monument to slain people from Šumadija in the wars Stone lion in Šumarice park, World War I memorial

Stone lion in Šumarice park, World War I memorial Zastava main gate

Zastava main gate.jpg) Densely populated city quarters

Densely populated city quarters City center

City center Main street

Main street

Notable people

- Milan Obrenović II, Prince of Serbia (1839)

- Mihailo Obrenović III, Prince of Serbia (1839–1842 and 1860–1868)

- Tomislav Nikolić, President of Serbia (2012–2017)

- Radomir Putnik, first Serbian Field Marshal (Voivoda), Chief of the General Staff (1890–1892, 1903–1905, 1908–1915), and Minister of Defense (1904–1905, 1906–1908, 1912)

- Jovan Ristić, President of the Ministry of Serbia (1867, 1873, 1878–1880, 1887–1888), Minister of Foreign Affairs (1867, 1872–1873, 1875, 1876–1880, 1887), and President of Serbian Academy of Science and Arts (1899)

- Dušan Simović, Chief of General Staff (1938–1940)

- Nikola Koka Janković, sculptor and full member of Serbian Academy of Science and Arts

- Radoje Domanović, writer and teacher

- Zoran Spasojević, writer

- Dragan Todorović, writer and multimedia artist

- Draginja Adamović, poet

- Dragiša Nedović, songwriter, composer and musician

- Vidosav Stevanović, novelist, story writer, poet, playwright and publicist

- Dragoslav Srejović, archaeologist and historian

- Nataša Kandić, founder of the Humanitarian Law Center

- Mirko Babić, actor

- Dragomir Bojanić Gidra, actor

- Branislav Jerinić, actor

- Gorica Popović, actor

- Nikola Rakočević, actor

- Milovan "Minimaks" Ilić, radio and television host

- Bora Dugić, flautist

- Cune Gojković, singer

- Marija Šerifović, singer, Eurovision Song Contest winner of 2007

- Jelena Tomašević, singer

- Vesna Despotović, Serbian basketball player, Olympic bronze medalist (1980), and EuroBasket bronze medalist (1980)

- Stevan Pletikosić, Serbian sport shooter, six time Olympic participant, Olympic bronze medalist (1992), two time ISSF World Shooting Championships silver medalist (1994, 2006), and European Shooting Championship silver medalist (1995)

- Nikola Lončar, Serbian basketball player, Olympic silver medalist (1996), FIBA World Championship gold medalist (1998), FIBA European Championship gold (1997) and bronze medalist (1999), and Euroleague champion with KK Partizan (1992)

- Katarina Bulatović, Montenegrin handball player, Olympic silver medalist (2012) and European Women's Handball Championship gold medalist (2012)

- Marija Lojpur, handball player, 2013 World Championship silver medalist

- Jelena Milovanović, basketball player, Olympic bronze medalist (2016) and EuroBasket Women 2015 gold medalist (2015)

- Predrag Đorđević, footballer

- Danko Lazović, footballer

- Stefan Ilić, footballer, World U-20 champion

- Ana Mihajlović, fashion model, winner of the 2002 Elite Model Look

- Aleksa Ristić, basketball player Fiba 3x3 Debrecen masters

- Đorđe Kostić, basketball player Fiba 3x3 Debrecen masters

- Ivan Nedeljković, basketball player Fiba 3x3 Debrecen masters

- Filip Popović, basketball player Fiba 3x3 Debrecen masters

International relations

Twin towns – Sister cities

Kragujevac is twinned with:[53]

|

Partnerships and cooperation

The town has other forms of cooperation and city friendship similar to the twin/sister city programmes with:

|

See also

Notes and references

- Notes

- Spasić, Živomir. Prestonica Kragujevac: prilozi istoriji Kneževine Srbije: 1818-1841. Prizma, 1998.

- References

- ↑ "Municipalities of Serbia, 2006". Statistical Office of Serbia. Retrieved 2010-11-28.

- ↑ "2011 Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in the Republic of Serbia: Comparative Overview of the Number of Population in 1948, 1953, 1961, 1971, 1981, 1991, 2002 and 2011, Data by settlements" (PDF). Statistical Office of Republic Of Serbia, Belgrade. 2014. ISBN 978-86-6161-109-4. Retrieved 2014-06-27.

- ↑ Archived 27 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Brane Kartalović (22 August 2017), "Kragujevac od paleolita do oslobođenja", Politika (in Serbian), p. 14

- ↑ "Tapu Tahrir Defteri 491: Ottoman government: Free Download & Streaming Internet Archive". Archive.org. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ↑ "Map of the Belgrade Pashaluk" (GIF). Terkepek.adatbank.transindex.ro. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ↑ "Kočina Krajina". Projekat Rastko. Retrieved 6 January 2016.

- ↑ "Photos of San Antonio – Images of San Antonio, Texas, USA". Members.virtualtourist.com. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ↑ "Kragujevac | Beautiful Serbia". Voiceofserbia.org. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Brane Kartalović (29 December 2017). "Kragujevac se seli na desnu obalu Lepenice" [Kragujevac moves over to the right bank of the Lepenica]. Politika (in Serbian).

- ↑ "History of Serbian Culture". Srpskoblago.org. 4 January 1994. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ↑ "Kragujevac (Stadt)". En.europeonline-magazine.eu. 21 October 1941. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ↑ "Kragujevac 1918". telecom.gov.sk. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- ↑ "Knjaževsko-Srpski Teatar". Joakimvujic.com. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ↑ "Kragujevac: Bed and breakfast in Kragujevac, Serbia". Hotel LAMA. 21 October 1941. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ↑ "Blic Online: "Engleska krvava bajka" u Kragujevcu". Blic.co.rs. Retrieved 16 September 2011.

- ↑ Stevan K. Pavlowitch (2008). Hitler's new disorder: the Second World War in Yugoslavia. Columbia University Press. p. 62. ISBN 0-231-70050-4.

- ↑ "Monument to the executed pupils (Kragujevac, Serbia): Address, Attraction Reviews". TripAdvisor. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ↑ Krvava Bajika profile, sites.google.com; accessed 2 August 2015.

- ↑ "Kragujevačka tragedija 1941". Spomen-park Kragujevački oktobar. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- ↑ "About Zastava Kragujevac". Voice of Serbia. Retrieved 6 January 2016.

- ↑ "Welcome to Zastava-arms". Zastava-arms.rs. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ↑ ""Collateral damage" and the workers of the Zastava factory". Marxist.com. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ↑ "Kragujevac-City Tour – Kuća Čolovića". Kucacolovica.com. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ↑ "Parks in Kragujevac". Tourist Organization of Kragujevac. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- ↑ "How to Arrive to Kragujevac?". Tourist Organization of Kragujevac. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- ↑ "How to arrive to Kragujevac". Tourist Organization of Kragujevac. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- ↑ "Public Transportation in Kragujevac". City Traffic Agency. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- ↑ "Public Transportation in Kragujevac". Tourist Organization of Kragujevac. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- ↑ "Parking in Kragujevac". Parking Service Kragujevac. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- ↑ "Statistical data for Kragujevac". City of Kragujevac. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- ↑ "Monthly and annual means, maximum and minimum values of meteorological elements for the period 1981–2010" (in Serbian). Republic Hydrometeorological Service of Serbia. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- ↑ "2011 Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in the Republic of Serbia" (PDF). stat.gov.rs. Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

- ↑ "Statistical Yearbook" (PDF). Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- ↑ "Инфраструктура: Званичан сајт града Крагујевца". Kragujevac.rs. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ↑ "Попис становништва, домаћинстава и станова 2011. у Републици Србији" (PDF). stat.gov.rs. Republički zavod za statistiku. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 August 2014. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- ↑ "24. седница ГИК-а – Седнице: Званичан сајт града Крагујевца". Kragujevac.rs. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ↑ "About Zastava Arms". Zastava Arms. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- ↑ "List of Bank in Serbia". National Bank of Serbia. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- ↑ "About Direktna Banka". Direktna Banka Kragujevac. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- ↑ "About Šumadija Sajam". Šumadija Sajam. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- ↑ "ОПШТИНЕ И РЕГИОНИ У РЕПУБЛИЦИ СРБИЈИ, 2017" (PDF). stat.gov.rs (in Serbian). Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- ↑ "Образовање: Званичан сајт града Крагујевца". Kragujevac.rs. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ↑ "Dobrodošli na skolazagluve.edu.rs – Škola za gluve Kragujevac". Skolazagluve.edu.rs. 27 January 2015. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ↑ "Музичка школа "др Милоје Милојевић"". Muzicka-kg.com. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ↑ "Škola Vukašin Marković". Sosovukasinmarkovickg.edu.rs. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ↑ "University of Kragujevac". Kg.ac.rs. 21 May 1976. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ↑ "Introduction". Ub.kg.ac.rs. 5 June 1985. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ↑ "National Museum of Kragujevac". Retrieved 6 January 2016.

- ↑ "Old Foundry Museum". Retrieved 6 January 2016.

- ↑ "History of Football Association of Serbia". Football Association of Serbia. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- ↑ "Federation of International Bandy-About-About FIB-National Federations-Serbia-Serbia". Archived from the original on 4 October 2009.

- ↑ "Kragujevac Twin Cities". © 2009 Information service of Kragujevac City. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- ↑ Yugoslav Survey. 19. Belgrade: Jugoslavija Publishing House. 1978. p. 146. ISSN 0044-1341.

- ↑ "Bielsko-Biała – Partner Cities". © 2008 Urzędu Miejskiego w Bielsku-Białej. Retrieved 10 December 2008.

- ↑ "Mostar Gradovi prijatelji" [Mostar Twin Towns]. Mostar Official City Website (in Macedonian). Archived from the original on 30 October 2013. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- ↑ "Opole Official Website – Twin Towns". (in English and Polish) © 2007–2009 Urząd Miasta Opola. Retrieved 18 June 2009.

- ↑ Vacca, Maria Luisa. "Comune di Napoli-Gemellaggi" [Naples – Twin Towns]. Comune di Napoli (in Italian). Archived from the original on 22 July 2013. Retrieved 8 August 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kragujevac. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Kragujevac. |

.jpg)