Savamala

| Savamala Савамала | |

|---|---|

| Urban neighbourhood | |

Savamala and new Sava Promenade | |

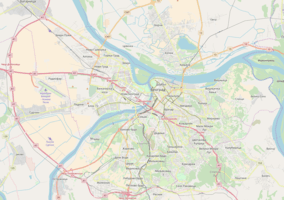

Savamala Location within Belgrade | |

| Coordinates: 44°48′48.6″N 20°27′08.3″E / 44.813500°N 20.452306°ECoordinates: 44°48′48.6″N 20°27′08.3″E / 44.813500°N 20.452306°E | |

| Country |

|

| Region | Belgrade |

| Municipality | Savski Venac/Stari Grad |

| Population (2011) | |

| • Total | 18,950 |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Area code | +381(0)11 |

| Car plates | BG |

Savamala (Serbian Cyrillic: Савамала) is an urban neighborhood of Belgrade, the capital of Serbia. It is located in Belgrade's municipalities of Savski Venac and Stari Grad.

Location

Savamala is located south of the Kalemegdan fortress and the neighborhood of Kosančićev Venac, and stretches along the right bank of the Sava river. Its northern section belongs to the municipality of Stari Grad, while central and southern sections belong to the municipality of Savski Venac. The central street in the neighborhood is Karađorđeva.

Originally, the entire western section (Terazije slopes) of today's city center was called Savamala, roughly bounded by the modern streets and squares of Terazije, King Milan's, Slavija, Nemanjina and Prince Miloš'. The entire area was known as Zapadni Vračar, but that name completely disappeared from usage, while as Savamala today is considered only a section along the Karađorđeva street.

Today, the zone of “preventive protection Savamala” is bounded by the steeets: Brankova, Kraljice Natalije, Dobrinjska, Admirala Geprata, Balkanska, Hajduk Veljkov venac, Sarajevska, Vojvode Milenka, Savska, Karađorđeva, Zemunski put and the Branko's bridge.[1] That means it encompasses the neighborhoods of Zeleni Venac and Terazijska Terasa.

History

First inhabitants were settled in the early 18th century, during the Austrian occupation of the northern Serbia 1717-39, when Austrians moved Christian population out of the Belgrade Fortress.[2]

The area was originally a bog called Ciganska bara (Serbian for "Gypsy pond"). The bog was charted for the first time in an Austrian map from 1789. It was a marsh which covered a wide area from modern Karađorđeva street to the mouth of the Topčiderska Reka into the Sava, across the northern tip of Ada Ciganlija. Marshy area covered modern location of the Belgrade Main railway station and parts of the Sarajevska and Hajduk-Veljkov venac streets. Ciganska bara drained two other bogs. One was located on Slavija, which drained through the creek which flew down the area of the modern Nemanjina street. Other pond whose water drained into the Ciganska bara was Zeleni Venac. Romanies who lived in the area, used the mud from the bog to make roof tiles. They lived in small huts or caravans (called "čerge"), between the high grass and rush, with their horses and water buffaloes grazing freely in the area. As most of the huts were actually stilt houses, built on piles due to the marshy land, the area was gradually named Bara Venecija ("Venice pond"). By 1884 the bog was drained and buried under the rubble from all parts of the city and especially from Prokop, because of the construction of the Belgrade Main railway station.[3]

Savamala was the first new settlement constructed outside the fortress walls of Kalemegdan. Construction began in the 1830s as ordered by the prince of Serbia, Miloš Obrenović, after a popular pressure to build a Serbian settlement outside the fortress and the Turkish settlement. Prince Miloš relocated the city’s port from the Danube to the Sava river and the customs house, called Đumrukana was built around 1835. The prince issued a decree that “merchants and trade agents must settle along the Sava”. By 1841, when Đumrukana was adapted into the first regular theatre house in Belgrade, the commerce blossomed and the „Kovačević Han“ was built where the modern Hotel Bristol is. „Beogradski mali pijac“ (Belgrade’s Little Greenmarket) was established at the center of Savamala and with the Karađorđeva street, became the focal point of city’s commerce. Storages and shops were abundant and the most esteemed merchants in Belgrade began buying lots and building houses: the Krsmanović brothers, Rista Paranos, Konstantin Antul, Luka Ćelović and Đorđe Vučo. State financially supported the construction of 46 shops, administrative building of the State Council (future “Odeon” cinema), building of the Ministry of Finance with the Financial Park (since 2017 Park Gavrilo Princip) and the Assencion Church. The first foreign consulate in Belgrade was opened in Savamala. It is recorded that in 1854, at the Liman section of Savamala (where the pillars of the Branko's Bridge are today), a trading caravan arrived with 550 big and 105 small camels. By the late 19th century, a tram line connected the peer with the Slavija Square.[1][2]

In the late 1820s, a popular Cannoneer's Greenmarket (Tobdžijska pijaca) was established, when Prince Miloš partially resettled inhabitants of Savamala to Palilula. It was located where the park on Hajduk Veljkov Venac is today. A building of the Ministry of Transportation was later built next to it. For the most part it had no permanent market stalls and the goods were sold directly of the carts.[4]

When Belgrade was divided into six quarters in 1860, Savamala was one of them.[5] By the census of 1883 it had a population of 5,547.[6] According to the further censuses, the population of Savamala was 6,981 in 1890, 6,516 in 1895, 8,033 in 1900, 9,504 in 1905, 9,567 in 1910 and 11,924 in 1921.[7][8]

Early 20th century was Savamala’s golden age. Through neighborhood, the spirit of modern Europe was rapidly arriving in Belgrade.[9] In 1900, the first ice rink in Belgrade was built near the railway station.[10] By 1914, it was the most densely populated area of Belgrade with arranged streets, primary school, first bank in Serbia and a quay along the bank of Sava was under construction. The area around the “Mali pijac” became to most prestigious one in the entire city and was affordable only to the wealthiest ones.[1] Having both the port and the railway by which visitors arrived, soon numerous hotels were built, both in Savamala and the Kosančićev Venac above it. Hotels Bosna and Bristol were built close to the port. There were also the hotels Solun and Petrograd, which was built on the Wilson's Square. Hotel Orient was located at the corner of the Hajduk-Veljkov Venac and Nemanjina streets, close to the Financial Park.[11]

Savamala was heavily bombarded in both world wars and partially demolished in the World War II. After 1948, state and city authorities favored the construction of New Belgrade so Savamala lost the importance it had. It became a transport hub and a transit route for commercial traffic which made it even less desirable neighborhood to live in due to the noise and air pollution. As a neglected neighborhood, in the 1960s Savamala became known for its local rascals, typical for the Belgrade at that time, when each neighborhood had ones. It had such a bad reputation that mothers would warn their misbehaving daughters that if they don’t act nice, they will “marry them into Savamala”.[1]

Characteristics

The name comes from the name of the Sava river and mahala, contracted usually to ma('a)la in Serbian, one of the Turkish words for neighbourhood or block of houses.

Due to its relative low altitude toward the Sava, and lack of any protection, Savamala is the only part of the central urban area of Belgrade that gets flooded during the extremely high waters of the river. It was almost completely flooded in 1984 and during the major floods in 2006.

Although considered as one of the most neglected parts of downtown Belgrade (mostly due to the very bad maintenance of the Karađorđeva street and surrounding buildings), Savamala is the location of many important traffic features in the city: the Karađorđeva street itself (with a railway parallel to it and the tram tracks), two bridges over the Sava (Brankov most and (Stari) Savski most), Belgrade Main Bus Station and bus station of the Lasta transportation company, Belgrade Main railway station and the Sava port (Savsko pristanište). The area (squares and parks) around the bus and train stations is known for prostitution and pornographic cinemas, further contributing to the already poor image of the neighborhood.

Out of many kafanas and shops, only few survived today. Kafana “Zlatna moruna” (Golden Beluga), built in the late 19the century, at the corner of the Kamenička and Kraljice Natalije streets, is one of the rare. Meeting point for the members of the revolutionary movement Young Bosnia prior to the World War I, it was restored in 2013. Confectionery store “Bosiljčić” in the Gavrila Principa street is the only one in Belgrade that still produces handmade candies.[1] University of Belgrade’s Faculty of Economics is located in Savamala.

Lagums, underground corridors beneath the Savamala, which were used as wine cellars, and the little known Armenian cemetery which was located on the slope beneath the Hotel Moskva, fell into oblivion.[2] Lagums are located along the Karađorđeva Street, being dug into the hill below Kosančićev Venac so that goods could be stored directly after being loaded off the boats in the port.[12]

One of the tallest edifices in the neighborhood is a nine-floor building of the Palace of Justice (Palata pravde), with a total floor area of 28,700 m2 (309,000 sq ft). A judiciary center, with several courts, prosecutors offices and detention rooms, it was built from 1969 to 1973. The building was closed in 2017 and all the judicial offices relocated due to the massive reconstruction which will be finished in 2019. In front of the Palace there is a monument to Emperor Dušan, holding Dušan's Code, a legal codification compiled in 1349.[13]

Sava Square

After the Main railway station was built in 1884, the area to the east developed into the square which, due to its location close both to the railway and the port, served for the transshipment of the goods, especially the cereals and grains, so in time it was named Žitni trg ("Grains square"). It was also well connected with the roads which lead outside of the city. It was directly connected with the road which is today the Savska Street in the direction of the Mostar neighborhood. There, it was splitting in two directions, one to the east (later neighborhoods of Jatagan Mala and Prokop) in the direction of Kragujevac in central Serbia, and the other to the south (neighborhoods of Senjak, Čukarica, Žarkovo) and further to the west Serbia.[14]

The square was renamed Vilsonov trg ("Wilson's Square") after World War I, in honor of the US president Woodrow Wilson and today in named Savski trg ("Sava Square"). Hotel "Petrograd" was built at the square and was mostly occupied by the visitors which stayed only for a few days in the city. It was especially popular among the travelers who arrived by the Orient Express. In the 1930s, the city developed further, as a series of new buildings stretching from the "Petrograd" were built along the Nemanjina Street, including the "Beograd" hotel and the Home of the Invalids.[14][11]

Landmarks

Some of the best-known landmarks of the neighborhood include:[1]

| Edifice | Address | Built | Architects | Protected | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manak's House | corner of Gavrila Principa 7 and Kraljevića Marka 12 | 1830 | cultural monument of exceptional importance from 1979 | named after its owner, merchant Manak Mihailović; today part of Ethnography Museum | |

| Mala Pijaca’s Cross | Park Bristol | 1862 | cultural monument from 1987 | merchant Ćira Hristić erected the black marble cross in memory of the fighters who died during the liberation of Belgrade from the Turks in 1806 | |

| Spanish House | Braće Krsmanović 2 | 1880 | formerly one of the most representative buildings in Belgrade, in the Academism style; belonged to the Belgrade port, Serbian shipping society and was a Museum of the river shipping; today in ruins with only the outer skeleton of side walls existing.[15] During World War I, in 1915 part of the building was adapted into the quarantine due to the outbreak of the typhus fever. After the war, the entire building was turned into a quarantine for the patients with Spanish flu, which gave the building its modern name.[16] | ||

| Belgrade Main railway station | Savski trg 1 | 1884 | Von Vlatich, Dragutin Milutinović | cultural monument of exceptional importance from 1983 | |

| Belgrade Cooperative | Karađorđeva 48 | 1905-1907 | Andra Stevanović, Nikola Nestorović | cultural monument of exceptional importance from 1979 | often cited as one of the most beautiful buildings in Belgrade; fully restored in 2014 |

| The House of Đorđe Vučo | Karađorđeva 61-61a | 1908 | Dimitrije T. Leko | cultural monument from 1997 | |

| Hotel Bristol | Karađorđeva 50 | 1910-1912 | Nikola Nestorović | cultural monument from 1987 | |

Population

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1981 | 26,585 | — |

| 1991 | 24,471 | −8.0% |

| 2002 | 23,781 | −2.8% |

| 2011 | 18,950 | −20.3% |

| Source: [17][18][19][20] | ||

The population of Savamala (local communities of West Vračar, Gavrilo Princip, Zeleni Venac and Slobodan Penezić Krcun) was 18,950 in 2011. It is estimated that in 2015, population of Savamala in its widest sense was around 35,000, which is only third of the population that lived in it in the 1950s.[1] The population of all three central Belgrade municipalities, Savski Venac, Stari Grad and Vračar, is steadily declining since the 1960s.

Artistic revitalization

In the 2010s few artistic enthusiasts began transforming Savamala into the new creative hub of Belgrade. Formerly representative buildings, but now completely dilapidated, became headquarters of the cultural organizations like Mixer house, Cultural Center “City” and Urban Incubator. They chronicled stories from the inhabitants about old Savamala and employed artists and designers to revitalize the area who painted many murals, renovated parks and set ice rinks. Also, they invited artists, architects and chefs from all over the world and organized exhibitions, work shops, concerts and lectures which are now held in Savamala almost on daily basis. With all this development, Savamala began attracting tourists and the night life was invigorated with many new performances, galleries, clubs and restaurants.[1] They were joined by the Society for the ambiental protection of Savamala which organizes yearly celebration of the Savamala Day.[2]

Mixer House, moved to Savamala in 2012 from the neighborhood of Dorćol and organize regular Mixer House Festival which has over 10,000 visitors. The festival consists of movies, musical and artistic performances, lectures and exhibitions. The Urban Incubator turned the “Spanish House” into a pavilion where they coordinated workshops, exhibitions, literary nights and seminars about architecture, urbanism, design, arts and culture.[1] Mixer House announced that it will move back to Dorćol in May 2017.[21] The reason they cited was the frequent pressure from the state authorities. It included constant demolition orders, politically instigated inspections of all kinds and ever-growing fiscal imposts. Finally, after being presented with an ultimatum by their landlord that in order to keep renting the Savamala premises they have to close "Miкsalište", humanitarian center for the refugees, Mixer House held a final performance on 27 April 2017.[22] After that, Mixer House moved to Sarajevo in September of the same year.

Savamala received worldwide attention due to its cultural renaissance. Articles about it were published in Financial Times and Wallstreet Journal, CNN devoted several reports to it, while The Guardian regularly follows the happenings in Savamala, placing it among top ten most inspirational places in the world.[1][21][23]

Future

Proposed projects

Savamala is the main section of the "Sava amphitheater" (Savski amfiteatar). It is a section bordered by the Karađorđeva and Savska streets (extending a bit outside of the Branko's Bridge and the Gazela bridge) in the old part of the city, and by the Vladimira Popovićа street in New Belgrade. It covers an area of 185 ha (460 acres), out of which 107 ha (260 acres) in the old section, 47 ha (120 acres) in New Belgrade and 31 ha (77 acres) of the water surface of the Sava. The term "Sava amphitheater" was coined by the architect Đorđe Kovljanski in 1923 when he projected a plan by which Savamala would be turned into an island.[24] Savamala was tackled by the 1985 International Competition for the enhancement of the structure of New Belgrade. Aleksandar Despić, vice president of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts at the time, authorized architect Miloš Perović to organize the teams of architects and create a new vision for Savamala. The conditions of the project included the reconstruction and revitalization of the neighborhood into the Belgrade's cultural hub, keeping the "historical matrix" and "nosatalgia of history". The project was presented in the gallery of the academy.[25]

In 1991 Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts held non-competitive contest and the most popular solution was a project by which Savamala and New Belgrade will be connected by the web of canals and an artificial island in the middle of the river, with residential, commercial and catering facilities. Another project, strongly pushed by the government at that time but highly unpopular as a concept, was the 1995 "Europolis project" which planned to cover entire section of Belgrade from Terazije to the Sava river with glass. In 2008 city began preparatory work on the first official urban plan for Savamala, but it was going slow. Propositions included the turning of the Main Railway Station into the museum and Savamala as the location of the future opera house or the building of the Belgrade Philharmonic Orchestra. Any project would have to include the removal of the railways and the main train and bus stations. One of the thing that the urbanists put in the plans as mandatory is a ban on highrise due to the panoramic view of Belgrade from the river (hence the "amphitheater" appearance). In its strategy, city government banned tall buildings in the old section of Belgrade.[26]

In July 2017, city urbanist MIlutin Folić announced the reconstruction of the Karađorđeva street from the Beton-Hala to the Branko's Bridge, along the southern border of Kosančićev Venac. The works, projected by Boris Podrecca, should start at the end of 2017 and will include: widening of the sidewalks, planting of the avenue, further reconstruction of the façades, relocation of the tramway closer to the river and placing them on the cobblestones and construction of the parking for the buses which pick up the tourists from the port.[27] Works were postponed for the summer of 2018. It was announced that the idea was to transform the entire section into the linear park, patterned after the High Line park in New York City, which would extend around the Belgrade Fortress and Dorćol, all the way to the Pančevo Bridge.[28] The planned 14-months long reconstruction was then postponed to September 2018, but it didn't start then either. The area set for reconstruction is 682 m (2,238 ft) long and covers 1 ha (2.5 acres).[9]

Fortress footbridge

In 2008 city administration announced that a footbridge (pasarela), which would directly connect the promenade and the port section at Beton-hala to the Belgrade Fortress, will be constructed. The idea of building panoramic elevators or establishing a cable car line was also considered. On the international architectural design competition "Center on the water", held in 2011, first prize was divided between the Japanese architect Sou Fujimoto and Serbian Branislav Redžić. Fujimoto's project, a spiral concrete object called "Cloud" (Oblak), was universally panned by the architects and citizens, but the mayor of Belgrade Dragan Đilas pushed the project. The experts called the Cloud aggressive and invasive: "it attacks the fortress and hides its beauty" and "invasive project which pushes the Belgrade Fortress into the background". Additionally, the price was €25.7 million. The administration wanted to combine the two projects, but Fujimoto vetoed it. After Đilas was removed from office in 2013, the project, which always remained only on paper, was abandoned. New administration signaled that they might use Redžić's project, but that didn't happen. In May 2015, a 2006-09 project of Mrđan Bajić and Richard Deacon with additional help from Branislav Mitrović, was chosen by the city. The project consists of a pedestrian bridge, panoramic glass elevator (just to the top of the stairs, not to the fortress) and a sculpture called "From there to here" (Odavde donde) around which the stairs will spiral. Between the stairs and the "Bella Vista" restaurant on the Sava bank a park will be formed, with a mini-fountain. The works began in October 2017 and are projected to last 14 months and cost 200 million dinars (€1.66 million).[29][30]

City architect Folić announced that the project will represent a city's symbolic river gate, as Belgrade already has Eastern City Gate and Western City Gate, while the sculpture "Tripod" in the neighborhood of Bogoslovija, announced in November 2017, will symbolize the northern gate.[31][32] When construction began, mayor Siniša Mali said that it will be finished by summer of 2018. President of the City Hall, Nikola Nikodijević, said in May that it will be open in August 2018. In August it was obvious that the works are not close to being complete and the city extended the deadline to November.[33] In September 2018, city announced that this is just phase 1 of the project. The footbridge won't be operational until 2019 and in the spring of that year the phase 2, or arrangement of the area below the footbridge will start. The price rose to 214 million dinars (€1.8 million). The sculpture itself weights 5 tons and is 7 m (23 ft) tall. It consists of two parts, the upper one made from stainless steel, work of Deacon, and the aluminum-made lower part, work of Bajić.[34]

Belgrade Waterfront

2016 Savamala incident

In April 2016 a controversy started about buildings that were suddenly demolished overnight in Savamala.[35] It is believed that this happened in order to make space for an Arabian-financed project on the Belgrade Waterfront.[36]

Savamala-Palilula tunnel

The idea of digging a tunnel which would connect Belgrade's section on the Sava slope with the area on the Danube slope existed for decades. In the late 1940s, the future entry point was even built near the crossroads of the Kamenička and Gavrila Principa streets. However the works had to be halted as, since the area is very prone to the mass wasting, the houses began sliding down towards the river. The hole was closed and concreted.[37]

Pushing their pet project, Belgrade Watefront, the city government announced in May 2017 that it has decided on the future route of the tunnel. From the direction of Savamala, it will enter underground apparently at the same place as planned before, near the Park Luka Ćelović and the University of Belgrade Faculty of Economics and will come out at the Stefan Bulevar Despota Stefana, near the building of the Belgrade City Police, with the total length of 1,993 m (6,539 ft). It will pass beneath Terazije (where it will reach its lowest, 38 m (125 ft) below ground) and Nikola Pašić Square. The tunnel will have two separate tubes for each direction. Each tube will be 9.56 m (31.4 ft) wide, with two 3.5 m (11 ft) wide lanes, two pedestrian pathways of 0.93 m (3 ft 1 in) and two evacuation exits for the vehicles. At the entry and exit points, 21 objects would have to be demolished, with the total area of 4,671 m2 (50,280 sq ft). Also, the Palilula exit section, streets of Cvijićeva and Dunavska, would have to be widened and adapted for the future traffic coming out of the tunnel. Analysis showed that the ground traffic will be relieved of 3,120 vehicles per hour, which will result in the reduction of the vehicle number in downtown by 10–15%, and driving time and carbon-dioxide emission by 10%. At Savamala entry point, there will be constructed a roundabout in Karađorđeva street to accommodate both the tunnel and the future new bridge on the Sava, after the surprising decision by the city authorities to demolish the Old Sava Bridge and build a new one. It is expected for the construction of the tunnel to begin in late 2018 and to be finished in 30 months, i.e., by the mid-2021. Original estimates placed the price of the project between 100 and 130 million euros, but the city government now claims that it will cost only 78 millions. Still, it is more of a conceptual design for now, as the full plans and projects are yet to be done.[38]

A detailed regulatory plan was made public in February 2018. It met with the disapproval of experts. Major objections include: lack of any cost or exploitation numbers in the plan; projected usage by personal cars only and general favoring of cars at the expense of pedestrians, cyclists and public transportation; lack of explanations and basis of the claims; assumed high price but lower commuting numbers, compared to the rail tunnels; confusion with the names of the neighborhood and the street where the tunnel ends; envisioned 90 degrees turn in the tunnel itself; provision that, "if necessary", the polluted air and smoke will be released in the city public areas above the tunnel (streets, parks); planned demolition of the wider urban tissue at the entry point; suggestion that, since the underground of Belgrade is plagued by groundwaters, the work should be done "during the dry season, when possible".[39]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Daliborka Mučibabić & Dejan Aleksić (15–16 February 2015). "Savamala – četvrt umetnosti I tri četvrti noćnog života" (in Serbian). Politika. p. 21.

- 1 2 3 4 Jelena Beoković, "Zaboravljeni život Savamale", Politika (in Serbian)

- ↑ Dragoljub Acković (December 2008), "Šest vekova Roma u Beograde – part XV, Veselje do kasno u noć", Politika (in Serbian)

- ↑ Dragan Perić (22 October 2017), "Beogradski vremeplov - Pijace: mesto gde grad hrani selo" [Belgrade chronicles - greenmarkets: a place where village feeds the city], Politika-Magazin, No. 1047 (in Serbian), pp. 26–27

- ↑ Dejan Aleksić (9 May 2017), "Šest decenija opštine Palilula - Nekad selo, a danas urbana celina grada", Politika (in Serbian)

- ↑ Belgrade by the 1883 census

- ↑ Претходни резултати пописа становништва и домаће стоке у Краљевини Србији 31 декембра 1910 године, Књига V, стр. 10 [Preliminary results of the census of population and husbandry in Kingdom of Serbia on 31 December 1910, Vol. V, page 10]. Управа државне статистике, Београд (Administration of the state statistics, Belgrade). 1911.

- ↑ Final results of the census of population from 31 January 1921, page 4. Kingdom of Yugoslavia - General State Statistics, Sarajevo. June 1932.

- 1 2 Dejan Aleksić (18 September 2018). "Бира се најповољнији понуђач, радови не пре октобра" [The most favorable contractor is being picked, works not before October]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 15.

- ↑ Nikola Belić (28 November 2010), "Led kreće, klizaljke na gotovs", Politika (in Serbian)

- 1 2 Dragan Perić (2 September 2018). "Kada su svi putevi vodili u Beograd" [When all roads were leading to Belgrade]. Politika-Magazin, No. 1092 (in Serbian). pp. 28–29.

- ↑ Nada Kovačević (2014), "Beograd ispod Beograda" [Belgrad beneath Belgrade], Politika (in Serbian)

- ↑ Aleksandra Petrović (6 August 2018). "Crvena opeka ostaje i u novom ruhu Palate pravde" [Red bricks remain in the new look of the Palace of Justice]. Politika (in Serbian). pp. 01 & 09.

- 1 2 Dragan Perić (20 May 2018). "Žitni trg ispred stanice" [Grains Square in front of the station]. Politika-Magazin, No. 1077 (in Serbian). p. 29.

- ↑ Daliborka Mučibabić (12 April 2013), "Španska kuća simbol preporoda Savamale", Politika (in Serbian), p. 19

- ↑ Borivoj B. Milaković (22 March 2018). "Otkud "španska" kuća u Beogradu" [How a "Spanish" house came to be in Belgrade]. Politika (in Serbian).

- ↑ Osnovni skupovi stanovništva u zemlji – SFRJ, SR i SAP, opštine i mesne zajednice 31.03.1981, tabela 191. Savezni zavod za statistiku (txt file). 1983.

- ↑ Stanovništvo prema migracionim obeležjima – SFRJ, SR i SAP, opštine i mesne zajednice 31.03.1991, tabela 018. Savezni zavod za statistiku (txt file). 1983.

- ↑ Popis stanovništva po mesnim zajednicama, Saopštenje 40/2002, page 4. Zavod za informatiku i statistiku grada Beograda. 26 July 2002.

- ↑ Stanovništvo po opštinama i mesnim zajednicama, Popis 2011. Grad Beograd – Sektor statistike (xls file). 23 April 2015.

- 1 2 "Doviđenja, Savamala: Mixer House se seli na Dorćol" (in Serbian). Blic. 24 January 2017.

- ↑ A.K. (28 April 2017), "Mikser iz Savamale ide na Dorćol", Politika (in Serbian), p. 20

- ↑ Will Coldwell (7 February 2015). "Belgrade's Savamala district: Serbia's new creative hub". The Guardian.

- ↑ Daliborka Mučibabić & Nikola Belić (11 April 2013), "Ponos socijalističke gradnje – centar biznisa i trgovine", Politika (in Serbian), p. 19

- ↑ Mihajlo Mitrović (15 June 2012), "Najzad, Savamala", Politika (in Serbian)

- ↑ Daliborka Mučibabić (7 May 2011), "Dragulj sapet kolosecima", Politika (in Serbian)

- ↑ Daliborka Mučibabić (22 July 2017), "Karađorđeva ulica čeka majstore", Politika (in Serbian), p. 15

- ↑ Daliborka Mučibabić (6 March 2018). "Linijski park po uzoru na njujorški Haj lajn" [Linear park tailored after the New York's High Line]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 15.

- ↑ Daliborka Mučibabić (3 October 2017), "Pešački most spaja reku i tvrđavu", Politika (in Serbian), p. 17

- ↑ Ričard Dikon i Mrđan Bajić predstavljaju projekat Most na Kalemegdanu, 27 May 2015

- ↑ Branka Vasiljević (16 November 2017), "Vizantijsko plavi "Tripod" kod Bogoslovije" [Byzantine blue 'Tripod" in Bogoslovija], Politika (in Serbian), p. 19

- ↑ "Beograd dobio Bulevar heroja sa Košara" [Belgrade got a Boulevard of the Heroes from Košare] (in Serbian). City of Belgrade. 7 November 2017.

- ↑ Istinomer team (6 September 2018). "Kalemegdansku pasarelu otvaramo u avgustu" [We open Kalemegdan footbridge in August] (in Serbian). Istinomer.

- ↑ Dejan Aleksić (25 September 2018). "Susret tvrđave i Save početkom novembra" [Meeting of the Sava and the fortress in early November]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 14.

- ↑ The Collapse of the Rule of Law in Serbia: the “Savamala” Case, Pointpulse

- ↑ Belgrade Waterfront, The Guardian

- ↑ Radoslav Ćebić (31 May 2018). "Tiranija Beograda na void" [Tyranny of the Belgrade Waterfront]. Vreme, No. 1430 (in Serbian).

- ↑ Dejan Aleksić, Daliborka Mučibabić (19 May 2017). "Tunel od 1,9 kilometara povezaće "Beograd na vodi" i Palilulu" (in Serbian). Politika. p. 17.

- ↑ Mihailo Maletin, et al., Academy of the engineering sciences of Serbia (23 February 2018). "Tunel za razmišljanje" [A tunnel to think about]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 23.