Vršac

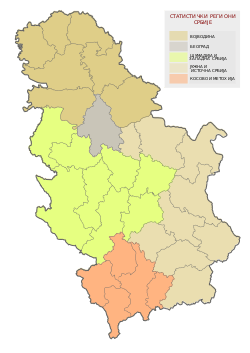

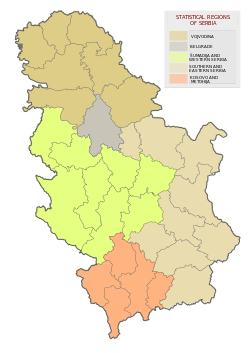

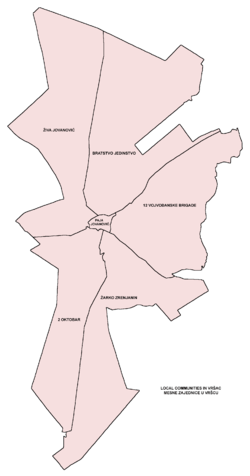

| Vršac Град Вршац | ||

|---|---|---|

| City | ||

| City of Vršac | ||

Panoramic view of Vršac | ||

| ||

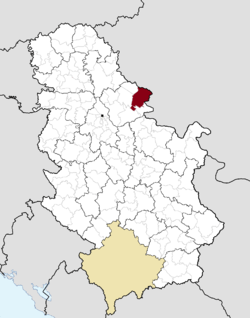

Location of Vršac within Serbia | ||

| Coordinates: 45°7′0″N 21°18′12″E / 45.11667°N 21.30333°ECoordinates: 45°7′0″N 21°18′12″E / 45.11667°N 21.30333°E | ||

| Country |

| |

| Province |

| |

| District | South Banat | |

| City status | March 2016 | |

| Government | ||

| • Mayor | Dragana Mitrović (SNS) | |

| Area | ||

| Area rank | 4th in Serbia | |

| • Area | 1,324 km2 (511 sq mi) | |

| Elevation | 93 m (305 ft) | |

| Population (2011) | ||

| • Urban | 35,701 | |

| • Rank | 30th in Serbia | |

| • Metro | 52,026 | |

| Demonym(s) | Vrščani, Vrščanka (sr) | |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) | |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) | |

| Postal code | 26300 | |

| Area code(s) | +381(0)13 | |

| Car plates | VŠ | |

| Website |

www | |

Vršac (Serbian Cyrillic: Вршац pronounced [ʋr̩̂ʃat͡s]) is a city located in the South Banat District of the autonomous province of Vojvodina, Serbia. As of 2011, the city urban area has a population of 35,701, while the city administrative area has 52,026 inhabitants. It is located in the geographical region of Banat.

Name

The name Vršac is of Serbian origin. It derived from the Slavic word vrh, meaning "summit".

In Serbian, the city is known as Вршац or Vršac, in Romanian as Vârșeț, in Hungarian as Versec or Versecz, in German as Werschetz, and in Turkish as Virșac or Verşe.

History

There are traces of human settlement in this area from paleolithic and neolithic times. Remains from two types of neolithic cultures have been discovered in the area: an older one, known as the Starčevo culture, and a newer one, known as the Vinča culture. From the Bronze Age, there are traces of the Vatin culture and Vršac culture, while from the Iron Age, there are traces of the Hallstatt culture and La Tène culture (which is largely associated with the Celts).

The Agathyrsi (people of mixed Scythian-Thracian origin) are the first people known to have lived in this region. Later, the region was inhabited by Getae and Dacians. It belonged to the Dacian kingdoms of Burebista and Decebalus, and then to the Roman Empire from 102 to 271. In Vršac, archaeologists have found traces of ancient Dacian and Roman settlements. Later, the region belonged to the Empire of the Huns, the Gepid and Avar kingdoms, and the Bulgarian Empire.

The Slavs settled in this region in the 6th century, and the Slavic tribe known as the Abodrites (Bodriči) was recorded as living in the area. The Slavs from the region were Christianized during the rule of the duke Ahtum in the 11th century. When duke Ahtum was defeated by the Kingdom of Hungary, the region was included in the latter state.

Information about the early history of the town is scant. According to Serbian historians, medieval Vršac was founded and inhabited by Serbs in 1425,[1][2] although it was under administration of the Kingdom of Hungary. The original name of the town is unknown. There are several theories that its first name was Vers, Verbeč, Veršet or Vegenje, but these theories are not confirmed. The name of the town appears for the first time in 1427 in the form Podvršan. The Hungarian 12th century chronicle known as Gesta Hungarorum mention the castle of Vrscia in Banat, which belonged to Romanian duke Glad in the 9th century. According to some interpretations, Vrscia is identified with modern Vršac,[3] while according to other opinions, it is identified with Orşova. According to some claims, the town was at first in the possession of the Hungarian kings, and later became property of a Hungarian aristocrat, Miklós Peréyi, ban of Severin. In the 15th century, the town was in the possession of the Serbian despot Đurađ Branković. According to some claims, it was donated to the despot by Hungarian king Sigismund in 1411. According to other sources, Vršac fortress was built by Đurađ Branković after the fall of Smederevo.[2]

The Ottomans destroyed the town in the 16th century, but it was soon rebuilt under Ottoman administration. In 1590/91, the Ottoman garrison in Vršac fortress was composed of one aga, two Ottoman officers and 20 Serb mercenaries. The town was seat of the local Ottoman authorities and of the Serbian bishop. In this time, its population was composed of Muslims and Serbs.[4]

In 1594, the Serbs in the Banat started large uprising against Ottoman rule, and Vršac region was centre of this uprising. The leader of the uprising was Teodor Nestorović, the bishop of Vršac. The size of this uprising is illustrated by the verse from one Serbian national song: "Sva se butum zemlja pobunila, Šest stotina podiglo se sela, Svak na cara pušku podigao!" ("The whole land has rebelled, a six hundred villages arose, everybody pointed his gun against the emperor").

The Serb rebels bore flags with the image of Saint Sava, thus the rebellion had a character of a holy war. The Sinan-paša that lead the Ottoman army ordered that green flag of Muhammad should be brought from Damascus to confront this flag with image of Saint Sava. Furthermore, the Sinan-paša also burned the mortal remains of Saint Sava in Belgrade, as a revenge to the Serbs. Eventually, the uprising was crushed and most of the Serbs from the region escaped to Transylvania fearing the Ottoman retaliation. However, since the Banat region became deserted after this, which alarmed the Ottoman authorities who needed people in this fertile land, the authorities promised to spare everyone who came back. The Serb population came back, but the amnesty did not apply to the leader of the rebellion, Bishop Teodor Nestorović, who was flayed as a punishment. The Banat uprising was one of the three largest uprisings in Serbian history and the largest before the First Serbian Uprising led by Karađorđe.

In 1716, Vršac passed from Ottoman to Habsburg control, and the Muslim population fled the town. In this time, Vršac was mostly populated by Serbs, and in the beginning of the Habsburg rule, its population numbered 75 houses. Soon, German colonists started to settle here. They founded a new settlement known as Werschetz, which was located near the old (Serbian) Vršac. Serbian Vršac was governed by a knez, and German Werschetz was governed by a schultheis (mayor). The name of the first Serbian knez in Vršac in 1717 was Jovan Crni. In 1795, the two towns, Serbian Vršac and German Werschetz, were officially joined into one single settlement, in which the authority was shared between Serbs and Germans. It was occupied by Ottomans between 1787-1788 during Russo-Turkish War (1787–1792).

The 1848/1849 revolution disrupted the good relations between Serbs and Germans, since Serbs fought on the side of the Austrian authorities and Germans fought on the side of the Hungarian revolutionaries. In 1848-1849, the town was part of autonomous Serbian Vojvodina, and from 1849 to 1860, it was part of the Voivodeship of Serbia and Temes Banat, a separate Austrian province. After the abolition of the voivodship, Vršac was included in Temes County of the Kingdom of Hungary, which became one of two autonomous parts of Austria-Hungary in 1867. The town was also a district seat. In 1910, the population of the town numbered 27,370 inhabitants, of whom 13,556 spoke German language, 8,602 spoke Serbian, 3,890 spoke Hungarian and 879 spoke Romanian.[5][6] On the other side, the Diocese of Vršac numbered 260.000 Romanians in 1847.

From 1918, the town was part of the newly formed Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (later renamed Yugoslavia). According to the 1921 census, speakers of German language were most numerous in the town, while the 1931 census recorded 13,425 speakers of Yugoslav languages and 11,926 speakers of German language. During the Axis occupation (1941–1944), Vršac was part of autonomous Banat region within the area governed by the Military Administration in Serbia. Many Danube Swabians collaborated with the Nazi authorities and many men were conscripted into the Waffen SS. Letters were sent to German men requesting their "voluntary service" or they would face court martial. In 1944, one part of Vršac citizens of German ethnicity left from the city, together with defeated German army.[7] Those who remained in Vršac were sent to local communist prison camps, where some of them died from disease and malnutrition. According to some claims, some were tortured or killed by the partisans. Since 1944 when it was liberated by the Red Army's 46th Army, the town was part of the new Socialist Yugoslavia. After prison camps were dissolved (in 1948) and Yugoslav citizenship was returned to the Germans, the remaining German population left Yugoslavia due to being forced out by the Russians. Homes that had been in their families for decades were simply taken over by the Serbs.[8]

Vršac was granted city status in February 2016.[9]

Inhabited places

The city of Vršac includes the settlement of Vršac and the following villages:

- Vatin

- Veliko Središte

- Vlajkovac

- Vojvodinci (Romanian: Voivodinţ)

- Vršački Ritovi

- Gudurica

- Zagajica

- Izbište

- Jablanka (Romanian: Iabuca)

- Kuštilj (Romanian: Coştei)

- Mali Žam (Romanian: Jamu Mic)

- Malo Središte (Romanian: Srediştea Mică)

- Markovac (Romanian: Mărcovăţ, Mărculești))

- Mesić (Romanian: Mesici)

- Orešac (Romanian: Oreşaţ)

- Pavliš (Romanian: Păuliş)

- Parta (Romanian Parța)

- Potporanj

- Ritiševo (Romanian: Râtişor)

- Sočica (Romanian: Sălciţa)

- Straža (Romanian: Straja)

- Uljma

- Šušara (Hungarian: Fejértelep)

Note: For the places with Romanian and Hungarian ethnic majorities, the names are also given in the language of the concerned ethnic group.

Demographics

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

| 1948 | 51,792 | — |

| 1953 | 55,594 | +1.43% |

| 1961 | 61,284 | +1.23% |

| 1971 | 60,528 | −0.12% |

| 1981 | 61,005 | +0.08% |

| 1991 | 58,228 | −0.46% |

| 2002 | 54,369 | −0.62% |

| 2011 | 52,026 | −0.49% |

| Source: [10] | ||

According to the 2011 census, the total population of the city of Vršac was 52,026 inhabitants.

Ethnic groups

Within the city, the settlements with a Serb ethnic majority are: Vršac (the city itself), Vatin, Veliko Središte, Vlajkovac, Vršački Ritovi, Gudurica, Zagajica, Izbište, Pavliš, Parta, Potporanj, and Uljma. The settlements with a Romanian ethnic majority are: Vojvodinci, Jablanka, Kuštilj, Mali Žam, Malo Središte, Markovac, Mesić, Ritiševo, Sočica, and Straža. Šušara has a Hungarian ethnic majority (Seklers collonised from Bukowina during the World War I), while Orešac is an ethnically mixed settlement with a Romanian plurality.

Vršac is the seat of the Serb Orthodox Eparchy of Banat. Some of the Serb cultural-artistic societies in Vršac are named "Laza Nančić", "Penzioner" and "Grozd". The city's Romanian minority have a Romanian-language theater, schools and a museum. Romanian-language instruction takes place at a kindergarten, an elementary school, a high school and a teachers' university. The cultural organization and folklore group "Luceafarul" hold many cultural events in Vršac and nearby Romanian-populated villages.[11][12] In 2005, Romania opened a consulate in Vršac.[13]

The population of the city (52,026 people) is composed of the following ethnic groups (2011 census):[14]

| Ethnic group | Population |

|---|---|

| Serbs | 37,595 |

| Romanians | 5,420 |

| Hungarians | 2,263 |

| Roma | 1,368 |

| Macedonians | 472 |

| Yugoslavs | 302 |

| Others | 4,606 |

| Total | 52,026 |

Economy and industry

Vršac is a city famous for well-developed industry, especially pharmaceuticals, wine and beer, confectioneries and textiles. The leading pharmaceutical company in Vršac (and nationwide) is the Hemofarm, which helped start the city's Technology Park.

Vršac is considered to be one of the most significant centers of agriculture in the region of southern Banat, which is the southern part of the province of Vojvodina. It is mainly because it has 54,000 hectares of arable and extremely fertile land in its possession.

The city itself together with 22 surrounding communities has some 52,000 residents, whose lives are closely connected with agriculture.

The following table gives a preview of total number of employed people per their core activity (as of 2016):[15]

| Activity | Total |

|---|---|

| Agriculture, forestry and fishing | 275 |

| Mining | 11 |

| Processing industry | 4,356 |

| Distribution of power, gas and water | 127 |

| Distribution of water and water waste management | 359 |

| Construction | 452 |

| Wholesale and retail, repair | 1,849 |

| Traffic, storage and communication | 713 |

| Hotels and restaurants | 515 |

| Media and telecommunications | 188 |

| Finance and insurance | 238 |

| Property stock and charter | 16 |

| Professional, scientific, innovative and technical activities | 501 |

| Administrative and other services | 357 |

| Administration and social assurance | 718 |

| Education | 940 |

| Healthcare and social work | 1,420 |

| Art, leisure and recreation | 176 |

| Other services | 188 |

| Total | 13,401 |

Transportation

Railways in the Vršac area | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

State Road 10 (which is part of European route E70) connects Vršac to Belgrade and to the nearby border with Romania.

Vršac is also connected to Belgrade by the Srbija voz railway line 44, and with a local train to Timişoara.

Tourist destinations

The Millennium sport center, opened in early-April 2001, is located in Vršac. The region around Vršac is famed for its vineyards.

Vršac Castle

The symbol of the town is the Vršac Castle (Vršačka kula), which dates back to the mid 15th century. It stands at the top of the hill (399m) overlooking Vršac.

There are two theories about origin of this fortress. According to the Turkish traveler, Evliya Çelebi, the fortress was built by the Serbian despot Đurađ Branković. The historians consider that Branković built the fortress after the fall of Smederevo in 1439. The fortress in its construction had some architectural elements similar to those in the fortress of Smederevo or in the fortress around monastery Manasija.

The other theory claim that Vršac Castle is a remain of the medieval fortress known as Erdesumulu (Hungarian: Érdsomlyó or Érsomlyó, Serbian: Erd-Šomljo / Ерд-Шомљо or Šomljo / Шомљо). However, the other sources do not identify Erdesumulu with Vršac, but claim that these two were separate settlements and that location of town and fortress of Erdesumulu was further to the east, on the Karaš River, in present-day Romanian Banat.

Monasteries

There are two Serbian Orthodox monasteries in the city: Mesić monastery from the 13th century and Središte monastery, which is currently under construction.

Churches

- The Serbian Orthodox Cathedral, completed in 1728.[16]

- The Romanian Orthodox Cathedral, completed in 1912.[17][18]

- The Roman Catholic Church, completed in 1863.[19]

Winery

One of interesting places to visit in Vršac is the family winery, Vinik, which produces the Vržole Red, Vržole White and Bermetto wine.

Gallery

Vršac town center

Vršac town center Vršac townhall

Vršac townhall Saint Nicholas Serbian Orthodox Cathedral in Vršac

Saint Nicholas Serbian Orthodox Cathedral in Vršac The Chapel Hill with the new Orthodox church and the old Exaltation of the Holy Cross Catholic Church.

The Chapel Hill with the new Orthodox church and the old Exaltation of the Holy Cross Catholic Church. The St. Gerhard Bishop and Martyr Catholic Church

The St. Gerhard Bishop and Martyr Catholic Church The Exaltation of the Holy Cross Catholic Church by night.

The Exaltation of the Holy Cross Catholic Church by night. Vrsac tower pictured from a nearby hill

Vrsac tower pictured from a nearby hill

Vinik winery in Vršac

Vinik winery in Vršac

Famous residents

- Marie von Augustin (1807–1886), Austrian female writer (de)

- Dragiša Brašovan, Serbian modernist architect

- Sultana Cijuk, an opera singer

- József Dietrich (1852–1884), Hungarian geographer and chemist of German (Danube Swabian) descent

- Robert Hammerstiel (born 1933), painter, artist (de)

- Ferenc Herczeg (1863–1954), Hungarian writer

- Milan Jovanović, photographer

- Paja Jovanović (1859–1957), famous Serbian painter

- Boris Kostić, chess player

- Felix Milleker, curator and first director of City Museum

- Dragan Mrđa, Serbian football player

- Teodor Nestorović, the bishop of Vršac and leader of the Serb uprising in Banat in 1594

- Nikola Nešković (1739–1775), Serbian painter

- Marijana Matthäus, Miodrag Kostić and Lothar Matthäus ex-wife

- Jovan Sterija Popović (1806–1856), Serbian playwright, dramatist, comediographer, and pedagogue of mixed Aromanian-Serb descent

- Nedeljko Popović Serba, painter

- Döme Sztójay (native name: Dimitrije Stojaković; 1883–1946), Hungarian Prime Minister and diplomat of Serb descent

- Zorana Todorović (1989-), basketball player

- Jenő Vincze (1908–1988), Hungarian international football player, most famous for playing for the Hungarian national team in the 1938 World Cup Final

- Nikola Cuculj (1958-), Wine maker of famous Vrzole wine and Great Knight of "Banat Wine Order St. Theodor"

- József Wodetzky (1872–1956), Hungarian astronomer of Polish descent[20]

- Tamara Radočaj (1987-), Serbian basketball player, Olympic bronze medalist and European champion

International relations

Consulate

Twin towns — sister cities

Vršac is twinned with:

Notes

- ↑ Dušan Belča, Mala istorija Vršca, Vršac, 1997, page 38.

- 1 2 "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 29 April 2011.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 19 June 2011.

- ↑ Dušan Belča, Mala istorija Vršca, Vršac, 1997, page 48.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 9 March 2006. Retrieved 27 March 2007.

- ↑ http://www.megaupload.com/?d=YKE9MH4B%5Bpermanent+dead+link%5D

- ↑ Dragomir Jankov, Vojvodina – propadanje jednog regiona, Novi Sad, 2004, page76, Quotation (English translation): "After the war, property of Germans in Vojvodina (where about 350,000 of them lived) was confiscated. Most of the Germans (about 200,000) left from Vojvodina together with German army....About 140,000 Germans was sent to camps".

- ↑ Nenad Stefanović, Jedan svet na Dunavu, Beograd, 2003, pages 174-176.

- ↑ "Pirot, Kikinda i Vršac dobili status grada" [Pirot, Kikinda and Vršac Granted City Status]. B92. 29 February 2016. Retrieved 26 June 2016.

- ↑ "2011 Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in the Republic of Serbia" (PDF). stat.gov.rs. Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

- ↑ 1ROMANII%20DIN%20BANATUL%20SARBESC.doc "Românii din Banatul Sârbesc"

- ↑ "comunitatea-romanilor.org.rs". www.comunitatea-romanilor.org.rs. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ↑ (in Romanian) Anca Alexe, "Consulat Nou" ("New Consulate"), Jurnalul Național, 22 January 2005

- ↑ "Population by ethnicity". Republic of Serbia Republic Statistical Office. Archived from the original on 16 April 2013. Retrieved 5 January 2014.

- ↑ "ОПШТИНЕ И РЕГИОНИ У РЕПУБЛИЦИ СРБИЈИ, 2017" (PDF). stat.gov.rs (in Serbian). Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ↑ "Saborna crkva u Vršcu". travel.rs. 14 November 2009. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ↑ "Sărbătoare românească la hramul catedralei din Vârşeţ". Archived from the original on 13 January 2013. Retrieved 10 March 2012.

- ↑ Biserica – Catedrala Înălţarea Domnului din Vârşeţ − monument al artei bizantine Archived 30 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Rimokatolička crkva u Vršcu". travel.rs. 14 November 2009. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 8 May 2007.

Further reading

- Dušan Belča, Mala istorija Vršca, Vršac, 1997.

- Dr. Dušan J. Popović, Srbi u Vojvodini, knjige 1-3, Novi Sad, 1990.

- Slobodan Ćurčić, Broj stanovnika Vojvodine, Novi Sad, 1996.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vršac. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Vršac. |