Smederevo

| Smederevo Град Смедерево | ||

|---|---|---|

| City | ||

| City of Smederevo | ||

| ||

| ||

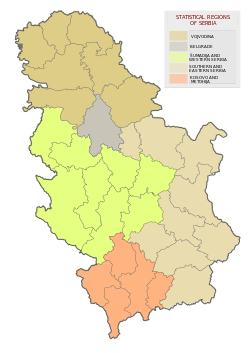

Location of the city of Smederevo within Serbia | ||

| Coordinates: 44°40′N 20°56′E / 44.667°N 20.933°ECoordinates: 44°40′N 20°56′E / 44.667°N 20.933°E | ||

| Country | Serbia | |

| Region | Southern and Eastern Serbia | |

| District | Podunavlje | |

| Settlements | 28 | |

| Government | ||

| • Mayor | Jasna Avramović (SNS) | |

| Area | ||

| • Urban | 42.03 km2 (16.23 sq mi) | |

| • Administrative | 484.30 km2 (186.99 sq mi) | |

| Elevation | 72 m (236 ft) | |

| Population (2011 census)[1] | ||

| • Rank | 13th in Serbia | |

| • Urban | 64,175 | |

| • Urban density | 1,500/km2 (4,000/sq mi) | |

| • Administrative | 108,209 | |

| • Administrative density | 220/km2 (580/sq mi) | |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) | |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) | |

| Postal code |

11300 11303 11304 11305 11330 | |

| Area code | +381(0)26 | |

| Car plates | SD | |

| Website |

www | |

Smederevo (Serbian Cyrillic: Смедерево, pronounced [smêdereʋo] (![]()

According to official results of the 2011 census, the city has a population of 64,105, and 108,209 people live in its administrative area.

Its history starts in the 1st century BC, with the conquerings of the Roman Empire, when there existed a town called Vinceia. The modern city traces its roots back to the late Middle Ages when it was the capital (1430–39, and 1444–59) of the last independent Serbian state before the Ottoman conquest.

Smederevo is said to be the city of iron (Serbian: gvožđe) and grapes (grožđe).

Names

In Serbian, the city is known as Smederevo (Смедерево), in Latin, Italian, Romanian and Greek as Semendria, in Hungarian as Szendrő or Vég-Szendrő, in Turkish as Semendire.

The name of Smederevo was first recorded in the Charter of the Byzantine Emperor Basil II from 1019, in the part related to the Eparchy of Braničevo (a suffragan diocese of the Archdiocese of Ochrid. Another written record is found in the Charter of Duke Lazar of Serbia from 1381, by which he bestowed the Monastery of Ravanica and villages and properties ’to the Great Bogosav with the commune and heritage’’.

The Latin-Italian name also occurs in Belogradum et Semendria and Belgrado e Semendria, two of the short-lived 20th-century synonyms of the Latin titular bishopric of Belgrade, which was suppressed in 1948 in favor of the residential Latin Archdiocese of Belgrade (Beograd) and 'newly' established titular bishopric of Alba marittima.

Coat of arms

Smederevo Coat of Arms uses two shades of blue, which deviates from the heraldic principles (only one shade of every color, contrasting those). Also, the bar with the year 1430 is placed over the shield. Emblem elements are six white discs arranged 3 + 2 + 1, which represents grapes, Smederevo fortress, dark blue and white horizontal lines (representing the Danube).

History

Early

In the 7th millennium BC, the Starčevo culture existed for a millennia, succeeded by the 6th millennium BC Vinča culture that prospered in the region. The Paleo-Balkan tribes of Dacians and Thracians emerged in the area in the 2nd millennia BC, with the Celtic Scordisci raiding the Balkans in the 3rd century B.C.

The Roman Empire conquered Vinceia in the 1st century BC. It was organized into Moesia, later Moesia Superior,[2] and in the administrative reforms of Diocletian (244–311) it was part of the Diocese of Moesia, then the Diocese of Dacia. It was a principal town of Moesia Superior, near the confluence of Margus and Brongus rivers.[3][4]

Middle Ages

The modern founder of the city was the Serbian prince Đurađ Branković in the 15th century, who built Smederevo Fortress in 1430 as the new Serbian capital. Smederevo was the residence of Branković and the capital of Serbia from 1430 until 1439, when it was conquered by the Ottoman Empire after a siege lasting two months.

Sanjak of Smederevo

In 1444, in accordance with the terms of the Peace of Szeged between the Kingdom of Hungary and the Ottoman Empire the Sultan returned Smederevo to Đurađ Branković, who was allied to John Hunyadi. On 22 August 1444 the Serb prince peacefully took possession of the evacuated town. When Hunyadi broke the peace treaty, Đurađ Branković remained neutral. Serbia became a battleground between the Kingdom of Hungary and the Ottomans, and the angry Branković captured Hunyadi after his defeat at the Second Battle of Kosovo in 1448. Hunyadi was imprisoned in Smederevo fortress for a short time.

In 1454 Sultan Mehmed II besieged Smederevo and devastated Serbia. The town was liberated by Hunyadi. In 1459 Smederevo was again captured by the Ottomans after the death of Branković. The town became a Turkish border-fortress, and played an important part in Ottoman–Hungarian Wars until 1526. Due to its strategic location, Smederevo was gradually rebuilt and enlarged. For a long period, the town was the capital of the Sanjak of Smederevo.

In autumn 1476, a joint army of Hungarians and Serbs tried to capture the fortress from the Ottomans. They built three wooden counter-fortresses, but after months of siege Sultan Mehmed II himself came to drive them away. After fierce fighting the Hungarians agreed to withdraw. In 1494 Pál Kinizsi tried to capture Smederevo from the Ottomans but he was stricken with palsy and died. In 1512 John Zápolya unsuccessfully laid siege to the town.

Modern

During the First Serbian Uprising in 1806, the city became the temporary capital of Serbia, as well as the seat of the Praviteljstvujušči sovjet, a government headed by Dositej Obradović. The first basic school was founded in 1806. During World War II, the city was occupied by German forces, who stored ammunition in the fortress. On 5 June 1941, a catastrophic explosion severely damaged the fortress, killing nearly 2,000 residents.

After World War II, Smederevo became an industrial and cultural center of Podunavlje district. Under the overall industrial development of Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, the city received a boost in infrastructure. Due to the ideal geographical position of Smederevo, socialist government supported building of roads, apartment buildings and tens of factories.

Some of the most notable factories built and renewed in period between 1950s until the end of 1980s were Zelvoz (Heroj Srba during the period of SFRJ), renewed in 1966. and a new steel plant built on outskirts of Smederevo at that time, Sartid (MKS during the period of SFRJ) which was completely operational in 1971.

Settlements

Aside the city of Smederevo, the administrative area includes the following 27 settlements (number of population according to 2011 census in bracket[1]):

|

Economy

Smederevo has a recent history of heavy industry and manufacturing, which is a result of active and aggressive industrialization of the region conducted by Tito's regime during the 1950s-1960s era. Previously, this entire geographical region had a heavy focus on agricultural production.

The city is home to the only operating steel mill in the country - Železara Smederevo, previously known as Sartid, which is situated in the suburb of Radinac. This was privatized and sold to U.S. Steel in 2003 for $33 million.[5] Following the global economic crisis, U.S. Steel sold the plant to the government of Serbia for a symbolic $1 to avoid closing the plant. The plant was renamed Železara Smederevo and at the time employed 5,400 workers.[6] In 2016, the Serbian government managed to strike a deal with a Chinese conglomerate Hesteel Group, which purchased the effective assets for $46 million.[7]

The "Milan Blagojević" home appliance factory is the second largest industry company in the city. Smederevo is also an agricultural area, with significant production of fruit and vines. However, the large agricultural combine "Godomin" has been in financial difficulty since the 1990s and is almost defunct as of 2005. The grape variety known as Smederevka is named after the city. The "Ishrana" factory is an important supplier of bakery products in northern and eastern Serbia.

A U.S.-Dutch consortium, Comico Oil, planned to build a $250 million oil refinery in the industrial zone of the city in 2012.[8] However, the consortium lost its permit to build the refinery after it failed to meet payment deadlines for the land lease a year later.[9]

- Economic preview

The following table gives a preview of total number of employed people per their core activity (as of 2016):[10]

| Activity | Total |

|---|---|

| Agriculture, forestry and fishing | 190 |

| Mining | 13 |

| Processing industry | 8,761 |

| Distribution of power, gas and water | 210 |

| Distribution of water and water waste management | 531 |

| Construction | 667 |

| Wholesale and retail, repair | 3,352 |

| Traffic, storage and communication | 1,160 |

| Hotels and restaurants | 538 |

| Media and telecommunications | 237 |

| Finance and insurance | 393 |

| Property stock and charter | 77 |

| Professional, scientific, innovative and technical activities | 573 |

| Administrative and other services | 387 |

| Administration and social assurance | 1,386 |

| Education | 1,808 |

| Healthcare and social work | 1,519 |

| Art, leisure and recreation | 235 |

| Other services | 512 |

| Total | 22,549 |

River traffic

Infrastructure of the river traffic of the city of Smederevo consists of Danube waterway, old port, marina, new port, terminal for liquid Jugopetrol loads, as well as smaller piers (gravel pits) which are located along the bank in the industrial zone. The port is registered for international traffic and is located in the very center of the City. It has reloading capacities which can realize 1.5 millions of freight tons a year. The city has significant development options in the area of river traffic, freight and passenger alike.

Tourism

Among the main tourist attractions in the city are the Smederevo Fortress and the Obrenović Villa.

There is an old white mulberry tree in the center of Smederevo. Called Karađorđev dud ("Karađorđe's mulberry"), it is estimated to be over 300 years old. Though there are no historical sources to specifically confirm that, it is believed that under this tree dizdar Muharem Guša, Ottoman commander of the fortress, handed over the keys to the city to Karađorđe on 8 November 1805, after the city was liberated during the First Serbian Uprising. In May 2018 the tree was declared a natural monument of the III category, as the first "living" monument in Smederevo. The three is supported by metallic pipes, but there is an initiative that two sculptures, shaped like a male and female hand, should be installed instead.[11]

Demographics

In the 2011 census, there was 108,209 residents in the city administrative area,[12] of which 101,908 were Serbs and 2,369 were Romani.[13]

Population change

The historical population for the current area of Smederevo, divided into urban and other is as follows:

1805-1941 (estimate)

| Year | 1805 | 1834 | 1874 | 1884 | 1900 | 1905 | 1910 | 1921 | 1931 | 1941 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban | 4,000 | |||||||||

| Other | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Total | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

1948-present [1]

| Year | 1948 | 1953 | 1961 | 1971 | 1981 | 1991 | 2002 | 2011 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban | ||||||||

| Other | 45,339 | |||||||

| Total | 59,545 |

Ethnicity

The ethnicity by respondent in the 2011 census in Smederevo is shown below:[14]

| Ethnic Group | Urban | Other | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| Serbs | 59,798 | 93.18% | 42,110 | 95.63% | 101,908 | 94.18% |

| Albanians | 45 | 0.07% | 6 | 0.01% | 51 | 0.05% |

| Bosniaks | 6 | 0.01% | 1 | 0.002% | 7 | 0.006% |

| Bulgarians | 18 | 0.03% | 9 | 0.02% | 27 | 0.02% |

| Bunjevci | 2 | 0.003% | 0 | 0% | 2 | 0.002% |

| Vlachs | 6 | 0.01% | 0 | 0% | 6 | 0.006% |

| Goranci | 11 | 0.02% | 0 | 0% | 11 | 0.01% |

| Yugoslavs | 87 | 0.14% | 23 | 0.06% | 110 | 0.1% |

| Hungarians | 99 | 0.15% | 21 | 0.05% | 120 | 0.11% |

| Macedonians | 224 | 0.35% | 167 | 0.38% | 291 | 0.27% |

| Muslims | 44 | 0.07% | 17 | 0.04% | 61 | 0.06% |

| Germans | 12 | 0.02% | 3 | 0.007% | 15 | 0.01% |

| Roma | 1,921 | 2.99% | 448 | 1.02% | 2,369 | 2.19% |

| Romanians | 23 | 0.04% | 44 | 0.1% | 67 | 0.06% |

| Russians | 27 | 0.04% | 10 | 0.02% | 37 | 0.03% |

| Slovaks | 8 | 0.01% | 5 | 0.01% | 13 | 0.01% |

| Slovenians | 17 | 0.03% | 3 | 0.007% | 20 | 0.02% |

| Ukrainians | 8 | 0.01% | 5 | 0.01% | 13 | 0.01% |

| Croats | 131 | 0.2% | 30 | 0.07% | 161 | 0.15% |

| Montenegrins | 235 | 0.37% | 36 | 0.08% | 271 | 0.25% |

| Other | 101 | 0.16% | 38 | 0.09% | 139 | 0.13% |

| Did not declare | 729 | 1.14% | 351 | 0.8% | 1,080 | 1% |

| Regional affiliation | 29 | 0.05% | 6 | 0.01% | 35 | 0.03% |

| Unknown | 591 | 0.92% | 801 | 1.82% | 1,392 | 1.29% |

| Total | 64,175 | 100.00% | 44,034 | 100.00% | 108,209 | 100.00% |

Twin towns

Smederevo is twinned with:

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Comparative overview of the number of population in 1948, 1953, 1961, 1971, 1981, 1991, 2002 and 2011, pod2.stat.gov.rs; accessed 15 October 2016.

- ↑ p. 317. Books.google.com. Retrieved 31 August 2012.

- ↑ p. 1310. Books.google.com. Retrieved 31 August 2012.

- ↑ Aaron Arrowsmith, A grammar of ancient geography: compiled for the use of King's College School (1832), p. 108, Hansard (London)

- ↑ Reuters Editorial. "Serbia looks east for quick steel plant sale". Reuters. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ↑ "Serbia buys U.S. Steel plant; Price: $1". CBSNews. 31 January 2012. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ↑ Insajder. "Zelezara Smederevo steel mill: China's offer accepted". Insajder.net. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ↑ "Comico Oil Wins Permit to Build $250 Million Refinery in Serbia". Bloomberg L.P. 13 March 2012.

- ↑ "Serb City Scraps Comico Oil Refinery Project on Deadline". Bloomberg L.P. 5 February 2013.

- ↑ "ОПШТИНЕ И РЕГИОНИ У РЕПУБЛИЦИ СРБИЈИ, 2017" (PDF). stat.gov.rs (in Serbian). Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. Retrieved 20 February 2018.

- ↑ Olivera Milošević (31 May 2018). "Karađorđev dud postao prirodno dobro" [Karađorđećs mulberry became natural monument]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 12.

- ↑ Census in the city of Smederevo, pop-stat.mashke.org; accessed 15 October 2016. (in Serbian)

- ↑ "Microsoft Word - tekst, REV.GN.doc" (PDF). Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ↑ ETHNICITY Data by municipalities and cities

- ↑ POTPISAN SPORAZUM O BRATIMLJENJU SMEDEREVA I TANGŠANA (latin) / ПОТПИСАН СПОРАЗУМ О БРАТИМЉЕЊУ СМЕДЕРЕВА И ТАНГШАНА (cyrillic) smederevskenovine.rs (in Serbian)

- ↑ Ozvaničena saradnja Tangšana i Smedereva danas.rs (in Serbian)

- ↑ Ozvaničena saradnja Tangšana i Smedereva podunavlje.info (in Serbian)

Sources

![]()

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Smederevo. |

- City of Smederevo www.smederevo.org.rs (in English) (in Serbian)

- Virtual walk through Smederevo www.360serbia.com (in Serbian)

- Visit Smederevo (Tourist Organization City of Smederevo) www.visitsmederevo (in English) (in Serbian)

- Smederevo's Autumn