Caucasus

| Caucasus | |

|---|---|

Topography of the Caucasus | |

| Countries[1] | |

| Partially recognized countries |

|

| Autonomous republics and federal regions | |

| Demonym | Caucasian |

| Time Zones | UTC+02:00, UTC+03:00, UTC+03:30, UTC+4:00, UTC+04:30 |

The Caucasus /ˈkɔːkəsəs/ or Caucasia /kɔːˈkeɪʒə/ is a region located at the border of Eastern Europe and Western Asia, situated between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea and occupied by Russia, Georgia, Azerbaijan, and Armenia.[1] A less common definition includes also portions of northwestern Iran and northeastern Turkey.[1][2][3]

It is home to the Caucasus Mountains including the Greater Caucasus mountain range, which acts as a natural barrier separating Eastern Europe from Western Asia, the latter including the Transcaucasia, Armenian Highland and Anatolia regions. Europe's highest mountain, Mount Elbrus, at 5,642 metres (18,510 ft) is located in the west part of the Greater Caucasus mountain range.

The Caucasus region is separated into northern and southern parts – the North Caucasus (Ciscaucasus) and Transcaucasus (South Caucasus), respectively. The Greater Caucasus mountain range in the north is within the Russian Federation, while the Lesser Caucasus mountain range in the south is occupied by several independent states, namely Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan, and the partially recognised Artsakh Republic.

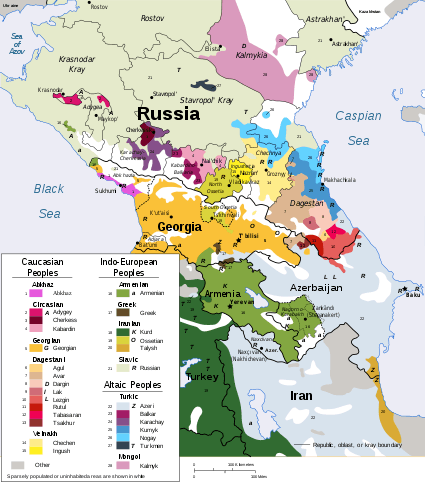

The region is known for its linguistic diversity: aside from Indo-European and Turkic languages, the Kartvelian, Northwest Caucasian, and Northeast Caucasian families are indigenous to the area.

Toponymy

Pliny the Elder's Natural History (77–79 AD) derives the name of the Caucasus from Scythian kroy-khasis ("ice-shining, white with snow").[4] German linguist Paul Kretschmer notes that the Latvian word Kruvesis also means "ice".[5][6]

In the Tale of Past Years (1113 AD), it is stated that Old East Slavic Кавкасийскыѣ горы (Kavkasijskyě gory) came from Ancient Greek Καύκασος (Kaukasos; later Greek pronunciation Kafkasos)),[7] which, according to M. A. Yuyukin, is a compound word that can be interpreted as the "Seagull's Mountain" (καύ-: καύαξ, καύηξ, ηκος ο, κήξ, κηϋξ "a kind of seagull" + the reconstructed *κάσος η "mountain" or "rock" richly attested both in place and personal names.)[8]

According to German philologists Otto Schrader and Alfons A. Nehring, the Ancient Greek word Καύκασος (Kaukasos) is connected to Gothic Hauhs ("high") as well as Lithuanian Kaũkas ("hillock") and Kaukarà ("hill, top").[7][9] British linguist Adrian Room points out that Kau- also means "mountain" in Pelasgian.[10]

The Transcaucasus region and Dagestan were the furthest points of Parthian and later Sasanian expansions, with areas to the north of the Greater Caucasus range practically impregnable. The mythological Mount Qaf, the world's highest mountain that ancient Iranian lore shrouded in mystery, was said to be situated in this region. In Middle Persian sources of the Sasanian era, the Caucasus range was referred to as Kaf Kof.[11] The term resurfaced in Iranian tradition later on in a variant form when Ferdowsi, in his Shahnameh, referred to the Caucasus mountains as Kōh-i Kāf.[11] "Most of the modern names of the Caucasus originate from the Greek Kaukasos (Lat., Caucasus) and the Middle Persian Kaf Kof".[11]

"The earliest etymon" of the name Caucasus comes from Kaz-kaz, the Hittite designation of the "inhabitants of the southern coast of the Black Sea".[11]

It was also noted that in Nakh Ков гас (Kov gas) means "gateway to steppe"[12]

Endonyms and exonyms

The modern name for the region is usually similar in the many languages, and is generally between Kavkaz and Kawkaz.

- Abkhazian: Кавказ Kavkaz

- Adyghe: Къаукъаз/с Kʺaukʺaz/s

- Azerbaijani: Qafqaz

- Arabic: القوقاز al-Qawqāz

- Armenian: Կովկաս Kovkas

- Avar: Кавказ Kawkaz

- Chechen: Кавказ Kavkaz

- Georgian: კავკასია K'avk'asia

- German: Kaukasien

- Greek: Καύκασος Káfkasos

- Hebrew: קווקז Qavqaz

- Ingush: Кавказ Kawkaz

- Karachay-Balkar: Кавказ Kavkaz

- Kumyk: Къавкъаз Qawqaz

- Kurdish: Qefqasya/Qefqas

- Lak: Ккавкказ Kkawkkaz

- Lezgian: Къавкъаз K'awk'az

- Mingrelian: კავკაცია K'avk'acia

- Ossetian: Кавказ Kavkaz

- Persian: قفقاز Qafqāz

- Russian: Кавказ Kavkaz

- Rutul: Qawqaz Kavkaz

- Turkish: Kafkaslar/Kafkasya

- Ukrainian: Кавказ Kavkaz

Political geography

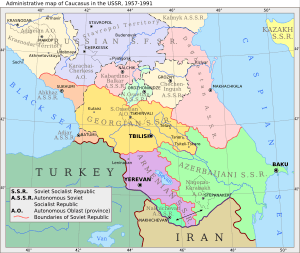

The North Caucasus region is known as the Ciscaucasus, whereas the South Caucasus region is commonly known as the Transcaucasus.

The Ciscaucasus contains most of the Greater Caucasus mountain range. It consists of Southern Russia, mainly the North Caucasian Federal District's autonomous republics, and the northernmost parts of Georgia and Azerbaijan. The Ciscaucasus lies between the Black Sea to its west, the Caspian Sea to its east, and borders the Southern Federal District to its north. The two Federal Districts are collectively referred to as "Southern Russia."

The Transcaucasus borders the Greater Caucasus range and Southern Russia to its north, the Black Sea and Turkey to its west, the Caspian Sea to its east, and Iran to its south. It contains the Lesser Caucasus mountain range and surrounding lowlands. All of Armenia, Azerbaijan (excluding the northernmost parts) and Georgia (excluding the northernmost parts) are in the South Caucasus.

The watershed along the Greater Caucasus range is generally perceived to be the dividing line between Europe and Southwest Asia. The highest peak in the Caucasus is Mount Elbrus (5,642 meters) located in western Ciscaucasus, and is considered as the highest point in Europe.

The Caucasus is one of the most linguistically and culturally diverse regions on Earth. The nation states that comprise the Caucasus today are the post-Soviet states Georgia (including Adjara), Azerbaijan (including Nakhchivan), Armenia, and the Russian Federation. The Russian divisions include Dagestan, Chechnya, Ingushetia, North Ossetia–Alania, Kabardino–Balkaria, Karachay–Cherkessia, Adygea, Krasnodar Krai and Stavropol Krai, in clockwise order.

Three territories in the region claim independence but are recognised as such by only a handful or by no independent UN countries: Artsakh, Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Abkhazia and South Ossetia are recognised by the majority of countries as part of Georgia, and Artsakh as part of Azerbaijan.

Azerbaijan's capital Baku

Azerbaijan's capital Baku

Demographics

The region has many different languages and language families. There are more than 50 ethnic groups living in the region.[14] No fewer than three language families are unique to the area. In addition, Indo-European languages, such as Armenian and Ossetian, and Turkic languages, such as Azerbaijani, Kumyk language and Karachay–Balkar, are spoken in the area. Russian is used as a lingua franca most notably in the North Caucasus.

The peoples of the northern and southern Caucasus tend to be either Sunni Muslims, Eastern Orthodox Christians and Armenian Christians. Twelver Shi'ism has many adherents in the southeastern part of the region, in Azerbaijan which extends into Iran.

History

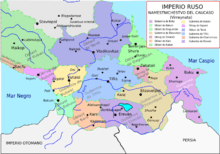

Located on the peripheries of Turkey, Iran, and Russia, the region has been an arena for political, military, religious, and cultural rivalries and expansionism for centuries. Throughout its history, the Caucasus was usually incorporated into the Iranian world.[15] At the beginning of the 19th century, the Russian Empire conquered the territory from Qajar Iran.[15]

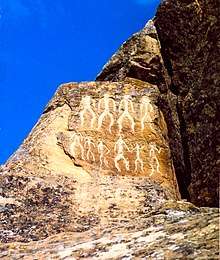

Prehistory

The territory of the Caucasus region was inhabited by Homo erectus since the Paleolithic Era. In 1991, early human (that is, hominin) fossils dating back 1.8 million years were found at the Dmanisi archaeological site in Georgia. Scientists now classify the assemblage of fossil skeletons as the subspecies Homo erectus georgicus.[16]

The site yields the earliest unequivocal evidence for presence of early humans outside the African continent;[17] and the Dmanisi skulls are the five oldest hominins ever found outside Africa, thereby doubling the presumed age of the human migration outside the continent.[18]

Antiquity

Kura–Araxes culture from about 4000 BC until about 2000 BC enveloped a vast area approximately 1,000 km by 500 km, and mostly encompassed, on modern-day territories, the Southern Caucasus (except western Georgia), northwestern Iran, the northeastern Caucasus, eastern Turkey, and as far as Syria.

Under Ashurbanipal (669–627 BC) the boundaries of the Assyrian Empire reached as far as the Caucasus Mountains. Later ancient kingdoms of the region included Armenia, Albania, Colchis and Iberia, among others. These kingdoms were later incorporated into various Iranian empires, including Media, the Achaemenid Empire, Parthia, and the Sassanid Empire, who would altogether rule the Caucasus for many hundreds of years. In 95–55 BC under the reign of Armenian king Tigranes the Great, the Kingdom of Armenia included Kingdom of Armenia, vassals Iberia, Albania, Parthia, Atropatene, Mesopotamia, Cappadocia, Cilicia, Syria, Nabataean kingdom, and Judea. By the time of the first century BC, Zoroastrianism had become the dominant religion of the region; however, the region would go through two other religious transformations. Owing to the strong rivalry between Persia and Rome, and later Byzantium, the latter would invade the region several times, although it was never able to hold the region.

Middle Ages

As the Arsacid dynasty of Armenia (an eponymous branch of the Arsacid dynasty of Parthia) was the first nation to adopt Christianity as state religion (in 301 AD), and Caucasian Albania and Georgia had become Christian entities, Christianity began to overtake Zoroastrianism and pagan beliefs. With the Muslim conquest of Persia, large parts of the region came under the rule of the Arabs, and Islam penetrated into the region.[19]

In the 10th century, the Alans (proto-Ossetians)[20] founded the Kingdom of Alania, that flourished in the Northern Caucasus, roughly in the location of latter-day Circassia and modern North Ossetia–Alania, until its destruction by the Mongol invasion in 1238–39.

During the Middle Ages Bagratid Armenia, Kingdom of Tashir-Dzoraget, Kingdom of Syunik and Principality of Khachen organized local Armenian population facing multiple threats after the fall of antique Kingdom of Armenia. Caucasian Albania maintained close ties with Armenia and the Church of Caucasian Albania shared same Christian dogmas with the Armenian Apostolic Church and had a tradition of their Catholicos being ordained through the Patriarch of Armenia.[21]

In the 12th century, the Georgian king David the Builder drove the Muslims out from Caucasus and made the Kingdom of Georgia a strong regional power. In 1194–1204 Georgian Queen Tamar's armies crushed new Seljuk Turkish invasions from the south-east and south and launched several successful campaigns into Seljuk Turkish-controlled Southern Armenia. The Georgian Kingdom continued military campaigns in the Caucasus region. As a result of her military campaigns and the temporary fall of the Byzantine Empire in 1204, Georgia became the strongest Christian state in the whole Near East area, encompassing most of the Caucasus stretching from Northern Iran and Northeastern Turkey to the North Caucasus.

The Caucasus region was conquered by the Ottomans, Mongols, local kingdoms and khanates, as well as, once again, Iran.

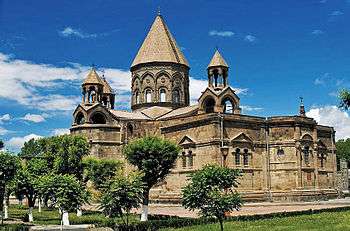

Etchmiadzin Cathedral in Armenia, original building completed in 303 AD, a religious centre of Armenia. It is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

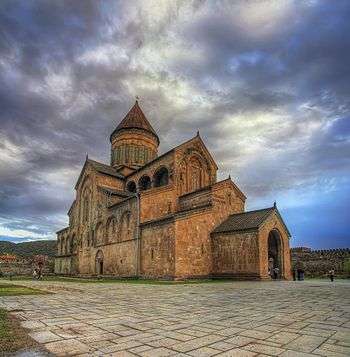

Etchmiadzin Cathedral in Armenia, original building completed in 303 AD, a religious centre of Armenia. It is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Svetitskhoveli Cathedral in Georgia, original building completed in the 4th century. It was a religious centre of monarchical Georgia. It is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Svetitskhoveli Cathedral in Georgia, original building completed in the 4th century. It was a religious centre of monarchical Georgia. It is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Northwest Caucasus caftan, 8-10th century, from the region of Alania.

Northwest Caucasus caftan, 8-10th century, from the region of Alania. Svaneti defensive tower houses

Svaneti defensive tower houses

Modern period

Up to including the early 19th century, the Southern Caucasus and southern Dagestan all formed part of the Persian Empire. In 1813 and 1828 by the Treaty of Gulistan and the Treaty of Turkmenchay respectively, the Persians were forced to irrevocably cede the Southern Caucasus and Dagestan to Imperial Russia.[22] In the ensuing years after these gains, the Russians took the remaining part of the Southern Caucasus, comprising western Georgia, through several wars from the Ottoman Empire.[23][24]

In the second half of the 19th century, the Russian Empire also conquered the Northern Caucasus. In the aftermath of the Caucasian Wars, an ethnic cleansing of Circassians was performed by Russia in which the indigenous peoples of this region, mostly Circassians, were expelled from their homeland and forced to move primarily to the Ottoman Empire.[25][26]

In the 1940s, around 480,000 Chechens and Ingush, 120,000 Karachay–Balkars and Meskhetian Turks, thousands of Kalmyks, and 200,000 Kurds in Nakchivan and Caucasus Germans were deported en masse to Central Asia and Siberia. About a quarter of them died.[27]

The Southern Caucasus region was unified as a single political entity twice – during the Russian Civil War (Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic) from 9 April 1918 to 26 May 1918, and under the Soviet rule (Transcaucasian SFSR) from 12 March 1922 to 5 December 1936. Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, Georgia, Azerbaijan and Armenia became independent nations.

The region has been subject to various territorial disputes since the collapse of the Soviet Union, leading to the Nagorno-Karabakh War (1988–1994), the East Prigorodny Conflict (1989–1991), the War in Abkhazia (1992–93), the First Chechen War (1994–1996), the Second Chechen War (1999–2009), and the 2008 South Ossetia War.

Mythology

In Greek mythology the Caucasus, or Kaukasos, was one of the pillars supporting the world. After presenting man with the gift of fire, Prometheus (or Amirani in Georgian version) was chained there by Zeus, to have his liver eaten daily by an eagle as punishment for defying Zeus' wish to keep the "secret of fire" from humans.

In Persian mythology the Caucasus might be associated with the mythic Mount Qaf which is believed to surround the known world. It is the battlefield of Saoshyant and the nest of the Simurgh.

The Roman poet Ovid placed Caucasus in Scythia and depicted it as a cold and stony mountain which was the abode of personified hunger. The Greek hero Jason sailed to the west coast of the Caucasus in pursuit of the Golden Fleece, and there met Medea, a daughter of King Aeëtes of Colchis.

Ecology

The Caucasus is an area of great ecological importance. The region is included in the list of 34 world biodiversity hotspots.[28][29] It harbors some 6400 species of higher plants, 1600 of which are endemic to the region.[30] Its wildlife includes Persian leopards, brown bears, wolves, bison, marals, golden eagles and hooded crows. Among invertebrates, some 1000 spider species are recorded in the Caucasus.[31][32] Most of arthropod biodiversity is concentrated on Great and Lesser Caucasus ranges.[32]

The region has a high level of endemism and a number of relict animals and plants, the fact reflecting presence of refugial forests, which survived the Ice Age in the Caucasus Mountains. The Caucasus forest refugium is the largest throughout the Western Asian (near Eastern) region.[33][34] The area has multiple representatives of disjunct relict groups of plants with the closest relatives in Eastern Asia, southern Europe, and even North America.[35][36][37] Over 70 species of forest snails of the region are endemic.[38] Some relict species of vertebrates are Caucasian parsley frog, Caucasian salamander, Robert's snow vole, and Caucasian grouse, and there are almost entirely endemic groups of animals such as lizards of genus Darevskia. In general, species composition of this refugium is quite distinct and differs from that of the other Western Eurasian refugia.[34]

The natural landscape is one of mixed forest, with substantial areas of rocky ground above the treeline. The Caucasus Mountains are also noted for a dog breed, the Caucasian Shepherd Dog (Rus. Kavkazskaya Ovcharka, Geo. Nagazi). Vincent Evans noted that minke whales have been recorded from the Black Sea.[39][40][41]

Energy and mineral resources

Caucasus has many economically important minerals and energy resources, such as alunite, gold, chromium, copper, iron ore, mercury, manganese, molybdenum, lead, tungsten, uranium, zinc, oil, natural gas, and coal (both hard and brown).

Tourism

Sport

2014 Winter Olympics venue, Sochi, Russia. Krasnaya Polyana — a popular centre of mountain skiing and a 2015 European Games snowboard venue. The first in the history of the European Games to be held in Azerbaijan.

Mountain-skiing complexes:

- Alpika-Service

- Mountain roundabout

- Rosa Hutor

- Tsaghkadzor Ski Resort in Armenia

- Shahdag Winter Complex in Azerbaijan

The Azerbaijan Grand Prix (motor racing) venue was the first in the history of Formula One to be held in Azerbaijan The Rugby World Cup U20 (rugby) was in Georgia (country) 2017

Cuisine

See also

- Khanates of the Caucasus

- Culture of Armenia

- Culture of Azerbaijan

- Culture of Georgia (country)

- Community for Democracy and Rights of Nations

- Eastern Europe

- Eastern Partnership

- Euronest Parliamentary Assembly

- Eurasian Economic Union

- Islam in Russia

- Prometheism

- Regions of Europe

- Transcontinental nations

- Transcaucasia

References

- 1 2 3 Caucasus in Encyclopedia Britannica

- ↑ "Where Is the Caucasus?"

- ↑ "The South Caucasus Region by the Caspian Sea"

- ↑ "Natural History," book six, chap. XVII

- ↑ Kretschmer, Paul (1928). "Weiteres zur Urgeschichte der Inder" [More about the Pre-History of the Indians]. Zeitschrift für vergleichende Sprachforschung auf dem Gebiete der indogermanischen Sprachen [Journal of Comparative Linguistic Research into Indo-European Philology] (in German). 55: 75–103.

- ↑ Kretschmer, Paul (1930). "Zeitschrift für vergleichende Sprachforschung auf dem Gebiete der indogermanischen Sprachen [Journal of Comparative Linguistic Research into Indo-European Philology]". 57: 251–255.

- 1 2 Vasmer, Max Julius Friedrich (1953–1958). "Russisches etymologisches Wörterbuch" [Russian Etymological Dictionary]. Indogermanische Bibliothek herausgegeben von Hans Krahe. Reihe 2: Wörterbüche [Indo-European Library Edited by Hans Krahe. Series 2: Dictionaries] (in German). 1. Heidelberg: Carl Winter.

- ↑ Yuyukin, M. A. (18–20 June 2012). "О происхождении названия Кавказ" [On the Origin of the Name of the Caucasus]. Индоевропейское языкознание и классическая филология – XVI (материалы чтений, посвященных памяти профессора И. М. Тронского) (in Russian). Saint Petersburg. pp. 893–899 and 919. ISBN 978-5-02-038298-5. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

- ↑ Schrader, Otto (1901). Reallexikon der indogermanischen Altertumskunde: Grundzüge einer Kultur- und Völkergeschichte Alteuropas [Real Lexicon of the Indo-Germanic Antiquity Studies: Basic Principles of a Cultural and People's History of Ancient Europe] (in German). Strasbourg: Karl J. Trübner.

- ↑ Room, Adrian (1997). Placenames of the World: Origins and Meanings of the Names for over 5000 Natural Features, Countries, Capitals, Territories, Cities, and Historic Sites. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-0172-7.

- 1 2 3 4 Gocheleishvili, Iago. "Caucasus, pre-900/1500". Encyclopaedia of Islam, THREE. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- ↑ Bolatojha J. "Древняя родина Кавкасов [The Ancient Homeland of the Caucasus]", p. 49, 2006.

- ↑ "ECMI – European Centre For Minority Issues Georgia". ecmicaucasus.org.

- ↑ "Caucasian peoples". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- 1 2 Multiple Authors. "Caucasus and Iran". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 2012-09-03.

- ↑ Derbyshire, David (9 September 2009). "Ancient Skeletons Discovered in Georgia Threaten to Overturn the Theory of Human Evolution". Mail Online.

Georgia may have been the cradle of the first Europeans...Archaeologists now believe that our ancestors left for Europe at least 1.8 million years ago, before returning to Africa and developing into Homo Sapiens...The Dmanisi bones may have belonged to an early Homo erectus which lived in Georgia before moving on to the rest of Europe.

- ↑ Vekua, A., Lordkipanidze, D., Rightmire, G. P., Agusti, J., Ferring, R., Maisuradze, G., et al. (2002). A new skull of early Homo from Dmanisi, Georgia. Science, 297:85–9.

- ↑ Perkins, Sid (2013). "Skull suggests three early human species were one". nature.com. doi:10.1038/nature.2013.13972.

- ↑ Hunter, Shireen; et al. (2004). Islam in Russia: The Politics of Identity and Security. M.E. Sharpe. p. 3.

(..) It is difficult to establish exactly when Islam first appeared in Russia because the lands that Islam penetrated early in its expansion were not part of Russia at the time, but were later incorporated into the expanding Russian Empire. Islam reached the Caucasus region in the middle of the seventh century as part of the Arab conquest of the Iranian Sassanian Empire.

- ↑ "Яндекс.Словари". yandex.ru.

- ↑ "Caucasian Albanian Church celebrates its 1700th Anniversary". The Georgian Church for English Speakers. 2013-08-09. Retrieved 2018-03-02.

- ↑ Timothy C. Dowling Russia at War: From the Mongol Conquest to Afghanistan, Chechnya, and Beyond pp 728–730 ABC-CLIO, 2 dec. 2014. ISBN 978-1598849486

- ↑ Suny, page 64

- ↑ Allen F. Chew. "An Atlas of Russian History: Eleven Centuries of Changing Borders", Yale University Press, 1970, p. 74

- ↑ Yemelianova, Galina, Islam nationalism and state in the Muslim Caucasus. Caucasus Survey, April 2014. p. 3

- ↑ Memoirs of Miliutin, "the plan of action decided upon for 1860 was to cleanse [ochistit'] the mountain zone of its indigenous population", per Richmond, W. The Northwest Caucasus: Past, Present, and Future. Routledge. 2008.

- ↑ Weitz, Eric D. (2003). A century of genocide: utopias of race and nation. Princeton University Press. p. 82. ISBN 0-691-00913-9.

- ↑ Zazanashvili N, Sanadiradze G, Bukhnikashvili A, Kandaurov A, Tarkhnishvili D. 2004. Caucasus. In: Mittermaier RA, Gil PG, Hoffmann M, Pilgrim J, Brooks T, Mittermaier CG, Lamoreux J, da Fonseca GAB, eds. Hotspots revisited, Earth's biologically richest and most endangered terrestrial ecoregions. Sierra Madre: CEMEX/Agrupacion Sierra Madre, 148–153

- ↑ "WWF – The Caucasus: A biodiversity hotspot". panda.org.

- ↑ "Endemic Species of the Caucasus".

- ↑ "A faunistic database on the spiders of the Caucasus". Caucasian Spiders. Archived from the original on 28 March 2009. Retrieved 17 September 2010.

- 1 2 Chaladze, G.; Otto, S.; Tramp, S. (2014). "A spider diversity model for the Caucasus Ecoregion". Journal of Insect Conservation. 18 (3): 407–416. doi:10.1007/s10841-014-9649-1.

- ↑ van Zeist W, Bottema S. 1991. Late Quaternary vegetation of the Near East. Wiesbaden: Reichert.

- 1 2 Tarkhnishvili, D.; Gavashelishvili, A.; Mumladze, L. (2012). "Palaeoclimatic models help to understand current distribution of Caucasian forest species". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 105: 231. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2011.01788.x.

- ↑ Milne RI. 2004. "Phylogeny and biogeography of Rhododendron subsection Pontica, a group with a Tertiary relict distribution". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 33: 389–401.

- ↑ Kikvidze Z, Ohsawa M. 1999. "Adjara, East Mediterranean refuge of Tertiary vegetation". In: Ohsawa M, Wildpret W, Arco MD, eds. Anaga Cloud Forest, a comparative study on evergreen broad-leaved forests and trees of the Canary Islands and Japan. Chiba: Chiba University Publications, 297–315.

- ↑ Denk T, Frotzler N, Davitashvili N. 2001. "Vegetational patterns and distribution of relict taxa in humid temperate forests and wetlands of Georgia Transcaucasia". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 72: 287–332.

- ↑ Pokryszko B, Cameron R, Mumladze L, Tarkhnishvili D. 2011. "Forest snail faunas from Georgian Transcaucasia: patterns of diversity in a Pleistocene refugium". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 102: 239–250

- ↑ The Status of Cetaceans in the Black Sea and Mediterranean Sea

- ↑ Horwood, Joseph (1989). Biology and Exploitation of the Minke Whale. p. 27.

- ↑ "Current knowledge of the cetacean fauna of the Greek Seas" (pdf). 2003: 219–232. Retrieved 2016-04-21.

http://site.rugby.ge/ka-ge/news-view/?newsid=4416&callerModID=17364

Sources

- Caucasus: A Journey to the Land Between Christianity and Islam, by Nicholas Griffin

- Small Nations and Great Powers: A Study of Ethnopolitical Conflict in the Caucasus, by Svante E. Cornell

- The Caucasus, by Ivan Golovin

- Suny, Ronald Grigor (1994). The Making of the Georgian Nation (2nd ed.). Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-20915-3.

- de Waal, Thomas (2010). The Caucasus: An Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-539977-3

- Coene, Frederick (2009). The Caucasus: An Introduction. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-48660-6

Further reading

- Nikolai F. Dubrovin. The history of wars and Russian domination in the Caucasus (История войны и владычества русских на Кавказе). Sankt-Petersburg, 1871–1888, at Runivers.ru in DjVu and PDF formats.

- Gagarin, G. G. Costumes Caucasus (Костюмы Кавказа). Paris, 1840, at Runivers.ru in DjVu and PDF formats.

- Gasimov, Zaur: The Caucasus, European History Online, Mainz: Institute of European History, 2011, retrieved: November 18, 2011.

- Rostislav A. Fadeev. Sixty years of the Caucasian War (Шестьдесят лет Кавказской войны). Tiflis, 1860, at Runivers.ru in DjVu format.

- Kaziev Shapi. Caucasian highlanders (Повседневная жизнь горцев Северного Кавказа в XIX в.). Everyday life of the Caucasian Highlanders. The 19th Century (In the co-authorship with I. Karpeev). "Molodaya Gvardiy" publishers. Moscow, 2003. ISBN 5-235-02585-7

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Caucasus. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Caucasus. |

- Articles and Photography on Artsakh (Nagorno-Karabakh) from UK Photojournalist Russell Pollard

- Information for travellers and others about Caucasus and Georgia

- Caucasian Review of International Affairs—an academic journal on the South Caucasus

- BBC News: North Caucasus at a glance, 8 September 2005

- United Nations Environment Programme map: Landcover of the Caucasus

- United Nations Environment Programme map: Population density of the Caucasus

- Food Security in Caucasus (FAO)

- Caucasus and Iran entry in Encyclopædia Iranica

- University of Turin-Observatory on Caucasus

- Circassians Caucasus Web (Turkish)

- Georgian Biodiversity Database (checklists for ca. 11,000 plant and animal species)

Coordinates: 42°15′40″N 44°07′16″E / 42.26111°N 44.12111°E