Horn of Africa

| Horn of Africa | |

|---|---|

| |

| Countries and territories |

|

| Major regional organizations | Arab League, Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa, Community of Sahel-Saharan States, Intergovernmental Authority on Development |

| Population | 122,618,170 (2016 est.) |

| Area | 1,882,757 km2 |

| Languages | |

| Religion | Christianity, Islam, traditional faiths, Judaism |

| Time zones | UTC+03:00 |

| Currency | |

| Capitals |

Addis Ababa (Ethiopia) Asmara (Eritrea) Djibouti (Djibouti) Hargeisa (Somaliland) Mogadishu (Somalia) |

| Total GDP (PPP) | $ 247.751 billion (2016) |

| Total GDP (nominal) | $ 102,057 billion (2016) |

The Horn of Africa is a peninsula in East Africa [1] that juts into the Guardafui Channel, lying along the southern side of the Gulf of Aden and the southwest Red Sea. The area is the easternmost projection of the African continent. The Horn of Africa denotes the region containing the countries of Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, and Somalia.[2][3][4][5] Regional studies on the Horn of Africa are carried out, among others, in the fields of Ethiopian Studies as well as Somali Studies.

Names

This peninsula is known by various names. In ancient and medieval times, the Horn of Africa was referred to as the Bilad al Barbar ("Land of the Berbers").[6][7][8] It is also known as the Somali peninsula, or in the Somali language, Geeska Afrika, Jasiiradda Soomaali or Gacandhulka Soomaali.[9] In other languages that are local or adjacent to the Horn of Africa, it is known as የአፍሪካ ቀንድ yäafrika qänd in Amharic, القرن الأفريقي al-qarn al-'afrīqī in Arabic, Gaaffaa Afriikaa in Oromo and ቀርኒ ኣፍሪቃ in Tigrinya. The Horn of Africa is sometimes shortened to HOA.[10] The Horn of Africa is quite commonly designated simply the "Horn", while inhabitants are sometimes colloquially referred to as Horn Africans.[11] Sometimes the term Greater Horn of Africa is used, either to be inclusive of neighbouring northeast African countries, or to distinguish the broader geopolitical definition of the Horn of Africa from narrower peninsular definitions.[12] Ancient Greeks and Romans referred to the Somali peninsula as Regio Aromatica or Regio Cinnamonifora due to the aromatic plants, or Regio Incognita owing to its unchartered territory, while ancient Egyptians referred to it as the Land of Punt.[13]

History

Prehistory

Shell middens 125,000 years old have been found in Eritrea,[14] indicating the diet of early humans included seafood obtained by beachcombing.

According to both genetic and fossil evidence, archaic Homo sapiens evolved into anatomically modern humans solely in Africa between 200,000 and 100,000 years ago and may have dispersed from the Horn of Africa.[15][16]

Today at the Bab-el-Mandeb straits, the Red Sea is about 12 miles (20 kilometres) wide, but 50,000 years ago it was much narrower and sea levels were 70 meters lower. Though the straits were never completely closed, there may have been islands in between which could be reached using simple rafts.

It has been estimated that from a population of 2,000 to 5,000 individuals in Africa,[17] only a small group of possibly as few as 150 to 1,000 people crossed the Red Sea.[18]

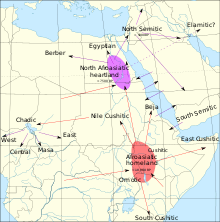

According to linguists, the first Afro-Asiatic-speaking populations arrived in the region during the ensuing Neolithic era from the family's proposed urheimat ("original homeland") in the Nile Valley,[19] or the Near East.[20] Other scholars propose that the Afro-Asiatic family developed in situ in the Horn, with its speakers subsequently dispersing from there.[21] Genetic analysis also indicates that, beginning in the pre-agricultural period, settlers from the Near East founded communities in Northeast Africa. These early settlements eventually gave rise to the Afro-Asiatic-speaking populations in the Horn and Maghreb as the groups spread.[22]

Ancient history

Together with northern Somalia, Djibouti, the Red Sea coast of Sudan and Eritrea is considered the most likely location of the land known to the ancient Egyptians as Punt (or "Ta Netjeru," meaning god's land), whose first mention dates to the 25th century BCE.[23]

Dʿmt was a kingdom located in Eritrea and northern Ethiopia, which existed during the 8th and 7th centuries BCE. With its capital at Yeha, the kingdom developed irrigation schemes, used plows, grew millet, and made iron tools and weapons. After the fall of Dʿmt in the 5th century BCE, the plateau came to be dominated by smaller successor kingdoms, until the rise of one of these kingdoms during the 1st century, the Aksumite Kingdom, which was able to reunite the area.[24]

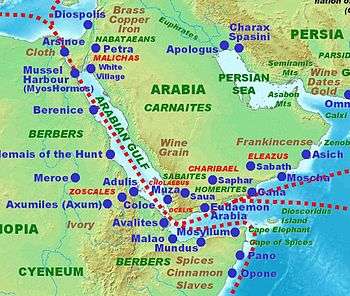

The Kingdom of Aksum (also known as the Aksumite Empire) was an ancient state located in the Eritrean highlands and Ethiopian highlands, which thrived between the 1st and 7th centuries CE. A major player in the commerce between the Roman Empire and Ancient India, Aksum's rulers facilitated trade by minting their own currency. The state also established its hegemony over the declining Kingdom of Kush and regularly entered the politics of the kingdoms on the Arabian peninsula, eventually extending its rule over the region with the conquest of the Himyarite Kingdom. Under Ezana (fl. 320–360), the kingdom of Aksum became the first major empire to adopt Christianity, and was named by Mani as one of the four great powers of his time, along with Persia, Rome and China.

Northern Somalia was an important link in the Horn, connecting the region's commerce with the rest of the ancient world. Somali sailors and merchants were the main suppliers of frankincense, myrrh and spices, all of which were valuable luxuries to the Ancient Egyptians, Phoenicians, Mycenaeans, Babylonians and Romans.[25][26] The Romans consequently began to refer to the region as Regio Aromatica. In the classical era, several flourishing Somali city-states such as Opone, Mosylon and Malao also competed with the Sabaeans, Parthians and Axumites for the rich Indo-Greco-Roman trade.[27]

The birth of Islam opposite the Horn's Red Sea coast meant that local merchants and sailors living on the Arabian Peninsula gradually came under the influence of the new religion through their converted Arab Muslim trading partners. With the migration of Muslim families from the Islamic world to the Horn in the early centuries of Islam, and the peaceful conversion of the local population by Muslim scholars in the following centuries, the ancient city-states eventually transformed into Islamic Mogadishu, Berbera, Zeila, Barawa and Merka, which were part of the Berber civilization.[28][29] The city of Mogadishu came to be known as the "City of Islam"[30] and controlled the East African gold trade for several centuries.[31]

Middle Ages and Early Modern era

During the Middle Ages, several powerful empires dominated the regional trade in the Horn, including the Adal Sultanate, the Ajuran Sultanate, the Warsangali Sultanate, the Zagwe dynasty, and the Sultanate of the Geledi.

The Sultanate of Showa, established in 896, was one of the oldest local Islamic states. It was centered in the former Shewa province in central Ethiopia. The polity was succeeded by the Sultanate of Ifat around 1285. Ifat was governed from its capital at Zeila in northern Somalia and was the easternmost district of the former Shewa Sultanate.[32]

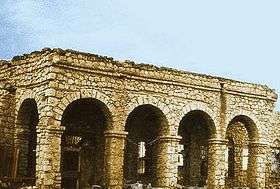

The Adal Sultanate was a medieval multi-ethnic Muslim state centered in the Horn region. At its height, it controlled large parts of Somalia, Ethiopia, Djibouti and Eritrea. Many of the historic cities in the region, such as Amud, Maduna, Abasa, Berbera, Zeila and Harar, flourished during the kingdom's golden age. This period that left behind numerous courtyard houses, mosques, shrines and walled enclosures. Under the leadership of rulers such as Sabr ad-Din II, Mansur ad-Din, Jamal ad-Din II, Shams ad-Din, General Mahfuz and Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi, Adalite armies continued the struggle against the Solomonic dynasty, a campaign historically known as the Conquest of Abyssinia or Futuh al Habash.

The Warsangali Sultanate was a kingdom centered in northeastern and in some parts of southeastern Somalia. It was one of the largest sultanates ever established in the territory, and, at the height of its power, included the Sanaag region and parts of the northeastern Bari region of the country, an area historically known as Maakhir or the Maakhir Coast. The Sultanate was founded in the late 13th century in northern Somalia by a group of Somalis from the Warsangali branch of the Darod clan, and was ruled by the descendants of the Gerad Dhidhin.

Through a strong centralized administration and an aggressive military stance towards invaders, the Ajuran Sultanate successfully resisted an Oromo invasion from the west and a Portuguese incursion from the east during the Gaal Madow and the Ajuran-Portuguese wars. Trading routes dating from the ancient and early medieval periods of Somali maritime enterprise were also strengthened or re-established, and the state left behind an extensive architectural legacy. Many of the hundreds of ruined castles and fortresses that dot the landscape of Somalia today are attributed to Ajuran engineers,[33] including a lot of the pillar tomb fields, necropolises and ruined cities built during that era. The royal family, the House of Gareen, also expanded its territories and established its hegemonic rule through a skillful combination of warfare, trade linkages and alliances.[34]

The Zagwe dynasty ruled many parts of modern Ethiopia and Eritrea from approximately 1137 to 1270. The name of the dynasty comes from the Cushitic-speaking Agaw people of northern Ethiopia. From 1270 onwards for many centuries, the Solomonic dynasty ruled the Ethiopian Empire.

In the early 15th century, Ethiopia sought to make diplomatic contact with European kingdoms for the first time since Aksumite times. A letter from King Henry IV of England to the Emperor of Abyssinia survives.[35] In 1428, the Emperor Yeshaq sent two emissaries to Alfonso V of Aragon, who sent return emissaries who failed to complete the return trip.[36]

The first continuous relations with a European country began in 1508 with Portugal under Emperor Lebna Dengel, who had just inherited the throne from his father.[37] This proved to be an important development, for when Abyssinia was subjected to the attacks of the Adal Sultanate General and Imam Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi (called "Gurey" or "Grañ", both meaning "the Left-handed"), Portugal assisted the Ethiopian emperor by sending weapons and four hundred men, who helped his son Gelawdewos defeat Ahmad and re-establish his rule.[38] This Abyssinian–Adal War was also one of the first proxy wars in the region as the Ottoman Empire, and Portugal took sides in the conflict.

When Emperor Susenyos converted to Roman Catholicism in 1624, years of revolt and civil unrest followed resulting in thousands of deaths.[39] The Jesuit missionaries had offended the Orthodox faith of the local Ethiopians. On June 25, 1632, Susenyos's son, Emperor Fasilides, declared the state religion to again be Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity, and expelled the Jesuit missionaries and other Europeans.[40][41]

During the end of 18th and the beginning of 19th century the Yejju dynasty (more specifically, the Warasek) ruled north Ethiopia changing the official language of Amhara people to Afaan Oromo, including inside the court of Gondar which was capital of the empire. Founded by Ali I of Yejju several successive descendants of him and Abba Seru Gwangul ruled with their army coming from mainly their clan the Yejju Oromo tribe as well as Wollo and Raya Oromo.[42]

The Sultanate of the Geledi was a Somali kingdom administered by the Gobroon dynasty, which ruled parts of the Horn of Africa during the 18th and 19th centuries. It was established by the Ajuran soldier Ibrahim Adeer, who had defeated various vassals of the Ajuran Empire and established the House of Gobroon. The dynasty reached its apex under the successive reigns of Sultan Yusuf Mahamud Ibrahim, who successfully consolidated Gobroon power during the Bardera wars, and Sultan Ahmed Yusuf, who forced regional powers such as the Omani Empire to submit tribute.

The Majeerteen Sultanate (Migiurtinia) was another prominent Somali sultanate based in the Horn region. Ruled by King Osman Mahamuud during its golden age, it controlled much of northeastern and central Somalia in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The polity had all of the organs of an integrated modern state and maintained a robust trading network. It also entered into treaties with foreign powers and exerted strong centralized authority on the domestic front.[43][44] Much of the Sultanate's former domain is today coextensive with the autonomous Puntland region in northeastern Somalia.[45]

The Sultanate of Hobyo was a 19th-century Somali kingdom founded by Sultan Yusuf Ali Kenadid. Initially, Kenadid's goal was to seize control of the neighboring Majeerteen Sultanate, which was then ruled by his cousin Boqor Osman Mahamuud. However, he was unsuccessful in this endeavor, and was eventually forced into exile in Yemen. A decade later, in the 1870s, Kenadid returned from the Arabian Peninsula with a band of Hadhrami musketeers and a group of devoted lieutenants. With their assistance, he managed to establish the kingdom of Hobyo, which would rule much of northeastern and central Somalia during the early modern period.[46]

Modern history

In the period following the opening of the Suez canal in 1869, when European powers scrambled for territory in Africa and tried to establish coaling stations for their ships, Italy invaded and occupied Eritrea. On January 1, 1890, Eritrea officially became a colony of Italy. In 1896 further Italian incursion into the horn was decisively halted by Ethiopian forces. By 1936 however, Eritrea became a province of Italian East Africa (Africa Orientale Italiana), along with Ethiopia and Italian Somaliland. By 1941, Eritrea had about 760,000 inhabitants, including 70,000 Italians.[47] The Commonwealth armed forces, along with the Ethiopian patriotic resistance, expelled those of Italy in 1941,[48] and took over the area's administration. The British continued to administer the territory under a UN Mandate until 1951, when Eritrea was federated with Ethiopia, as per UN resolution 390(A) and under the prompting of the United States adopted in December 1950.

.jpg)

The strategic importance of Eritrea, due to its Red Sea coastline and mineral resources, was the main cause for the federation with Ethiopia, which in turn led to Eritrea's annexation as Ethiopia's 14th province in 1952. This was the culmination of a gradual process of takeover by the Ethiopian authorities, a process which included a 1959 edict establishing the compulsory teaching of Amharic, the main language of Ethiopia, in all Eritrean schools. The lack of regard for the Eritrean population led to the formation of an independence movement in the early 1960s (1961), which erupted into a 30-year war against successive Ethiopian governments that ended in 1991. Following a UN-supervised referendum in Eritrea (dubbed UNOVER) in which the Eritrean people overwhelmingly voted for independence, Eritrea declared its independence and gained international recognition in 1993.[49] In 1998, a border dispute with Ethiopia led to the Eritrean-Ethiopian War.[50]

From 1862 until 1894, the land to the north of the Gulf of Tadjoura situated in modern-day Djibouti was called Obock and was ruled by Somali and Afar Sultans, local authorities with whom France signed various treaties between 1883 and 1887 to first gain a foothold in the region.[51][52][53] In 1894, Léonce Lagarde established a permanent French administration in the city of Djibouti and named the region Côte française des Somalis (French Somaliland), a name which continued until 1967.

In 1958, on the eve of neighboring Somalia's independence in 1960, a referendum was held in the territory to decide whether or not to join the Somali Republic or to remain with France. The referendum turned out in favour of a continued association with France, partly due to a combined yes vote by the sizable Afar ethnic group and resident Europeans.[54] There was also reports of widespread vote rigging, with the French expelling thousands of Somalis before the referendum reached the polls.[55] The majority of those who voted no were Somalis who were strongly in favour of joining a united Somalia, as had been proposed by Mahmoud Harbi, Vice President of the Government Council. Harbi was killed in a plane crash two years later.[54] Djibouti finally gained its independence from France in 1977, and Hassan Gouled Aptidon, a Somali politician who had campaigned for a yes vote in the referendum of 1958, eventually wound up as the nation's first president (1977–1999).[54] In early 2011, the Djiboutian citizenry took part in a series of protests against the long-serving government, which were associated with the larger Arab Spring demonstrations. The unrest eventually subsided by April of the year, and Djibouti's ruling People's Rally for Progress party was re-elected to office.

Mohammed Abdullah Hassan's Dervish State successfully repulsed the British Empire four times and forced it to retreat to the coastal region.[56] Due to these successful expeditions, the Dervish State was recognized as an ally by the Ottoman and German Empires. The Turks also named Hassan Emir of the Somali nation,[57] and the Germans promised to officially recognize any territories the Dervishes were to acquire.[58] After a quarter of a century of holding the British at bay, the Dervishes were finally defeated in 1920 as a direct consequence of Britain's new policy of aerial bombardment.[59] As a result of this bombardment, former Dervish territories were turned into a protectorate of Britain. Italy faced similar opposition from Somali Sultans and armies, and did not acquire full control of parts of modern Somalia until the Fascist era in late 1927. This occupation lasted until 1941, and was replaced by a British military administration. Northern Somalia would remain a protectorate, while southern Somalia became a trusteeship. The Union of the two regions in 1960 formed the Somali Republic. A civilian government was formed, and on July 20, 1961, through a popular referendum, a new constitution that had first been drafted the year before was ratified.[60]

Due to its longstanding ties with the Arab world, Somalia was accepted in 1974 as a member of the Arab League.[61] During the same year, the nation's former socialist administration also chaired the Organization of African Unity, the predecessor of the African Union.[62] In 1991, the Somali Civil War broke out, which saw the collapse of the federal government and the emergence of numerous autonomous polities, including the Puntland administration in the northeast and Somaliland, an unrecognised self-declared sovereign state that is internationally recognised as an autonomous region of Somalia,[63] in the northwest. Somalia's inhabitants subsequently reverted to local forms of conflict resolution, either secular, Islamic or customary law, with a provision for appeal of all sentences. A Transitional Federal Government was subsequently created in 2004.[64] The Federal Government of Somalia was established on August 20, 2012, concurrent with the end of the TFG's interim mandate.[65] It represents the first permanent central government in the country since the start of the civil war.[65] The Federal Parliament of Somalia serves as the government's legislative branch.[66]

Modern Ethiopia and its current borders are a result of significant territorial reduction in the north and expansion in the east and south toward its present borders, owing to several migrations, commercial integration, treaties as well as conquests, particularly by Emperor Menelik II and Ras Gobena.[67] From the central province of Shoa, Menelik set off to subjugate and incorporate ‘the lands and people of the South, East and West into an empire.’[67][68] He did this with the help of Ras Gobena's Shewan Oromo militia, began expanding his kingdom to the south and east, expanding into areas that had not been held since the invasion of Ahmad ibn Ibrihim al-Ghazi, and other areas that had never been under his rule, resulting in the borders of Ethiopia of today.[69] Menelik had signed the Treaty of Wichale with Italy in May 1889, in which Italy would recognize Ethiopia’s sovereignty so long as Italy could control a small area of northern Tigray (part of modern Eritrea).[70] In return Italy, was to provide Menelik with arms and support him as emperor.[71] The Italians used the time between the signing of the treaty and its ratification by the Italian government to further expand their territorial claims. Italy began a state funded program of resettlement for landless Italians in Eritrea, which increased tensions between the Eritrean peasants and the Italians.[71] This conflict erupted in the Battle of Adwa on 1 March 1896, in which Italy’s colonial forces were defeated by the Ethiopians.[72]

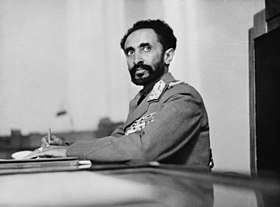

The early 20th century in Ethiopia was marked by the reign of Emperor Haile Selassie I, who came to power after Iyasu V was deposed. In 1935, Haile Selassie's troops fought and lost the Second Italo-Abyssinian War, after which point Italy annexed Ethiopia to Italian East Africa.[73] Haile Selassie subsequently appealed to the League of Nations, delivering an address that made him a worldwide figure and 1935's Time magazine Man of the Year.[74] Following the entry of Italy into World War II, British Empire forces, together with patriot Ethiopian fighters, liberated Ethiopia in the course of the East African Campaign in 1941.[75]

Haile Selassie's reign came to an end in 1974, when a Soviet-backed Marxist-Leninist military junta, the Derg led by Mengistu Haile Mariam, deposed him, and established a one-party communist state, which was called the People's Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. In July 1977, the Ogaden War broke out after the government of President of Somalia Siad Barre sought to incorporate the predominantly Somali-inhabited Ogaden region into a Pan-Somali Greater Somalia. By September 1977, the Somali army controlled 90% of the Ogaden, but was later forced to withdraw after Ethiopia's Derg received assistance from the USSR, Cuba, South Yemen, East Germany[76] and North Korea, including around 15,000 Cuban combat troops.

In 1989, the Tigrayan Peoples' Liberation Front (TPLF) merged with other ethnically based opposition movements to form the Ethiopian Peoples' Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), and eventually managed to overthrow Mengistu's dictatorial regime in 1991. A transitional government, composed of an 87-member Council of Representatives and guided by a national charter that functioned as a transitional constitution, was then set up. The first free and democratic election took place later in 1995, when Ethiopia's longest-serving Prime Minister Meles Zenawi was elected to office. As with other nations in the Horn region, Ethiopia maintained its historically close relations with countries in the Middle East during this period of change.[77] Zenawi died in 2012, but his Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) party remains the ruling political coalition in Ethiopia.

Geography

Geology and climate

The Horn of Africa is almost equidistant from the equator and the Tropic of Cancer. It consists chiefly of mountains uplifted through the formation of the Great Rift Valley, a fissure in the Earth's crust extending from Turkey to Mozambique and marking the separation of the African and Arabian tectonic plates. Mostly mountainous, the region arose through faults resulting from the Rift Valley.

Geologically, the Horn and Yemen once formed a single landmass around 18 million years ago, before the Gulf of Aden rifted and separated the Horn region from the Arabian Peninsula.[78][79] The Somali Plate is bounded on the west by the East African Rift, which stretches south from the triple junction in the Afar Depression, and an undersea continuation of the rift extending southward offshore. The northern boundary is the Aden Ridge along the coast of Saudi Arabia. The eastern boundary is the Central Indian Ridge, the northern portion of which is also known as the Carlsberg Ridge. The southern boundary is the Southwest Indian Ridge.

Extensive glaciers once covered the Simien and Bale Mountains but melted at the beginning of the Holocene. The mountains descend in a huge escarpment to the Red Sea and more steadily to the Indian Ocean. Socotra is a small island in the Indian Ocean off the coast of Somalia. Its size is 3,600 km2 (1,390 sq mi) and it is a territory of Yemen.

The lowlands of the Horn are generally arid in spite of their proximity to the equator. This is because the winds of the tropical monsoons that give seasonal rains to the Sahel and the Sudan blow from the west. Consequently, they lose their moisture before reaching Djibouti and Somalia, with the result that most of the Horn receives little rainfall during the monsoon season.

In the mountains of Ethiopia, many areas receive over 2,000 mm (80 in) per year, and even Asmara receives an average of 570 mm (23 in). This rainfall is the sole source of water for many areas outside Ethiopia, including Egypt. In the winter, the northeasterly trade winds do not provide any moisture except in mountainous areas of northern Somalia, where rainfall in late autumn can produce annual totals as high as 500 mm (20 in). On the eastern coast, a strong upwelling and the fact that the winds blow parallel to the coast means annual rainfall can be as low as 50 mm (2 in).

The climate in Ethiopia varies considerably between regions. It is generally hotter in the lowlands and temperate on the plateau. At Addis Ababa, which ranges from 2,200 to 2,600 m (7,218 to 8,530 ft), maximum temperature is 26 °C (78.8 °F) and minimum 4 °C (39.2 °F). The weather is usually sunny and dry, but the short (belg) rains occur from February to April and the big (meher) rains from mid-June to mid-September. The Danakil Desert stretches across 100,000 km2 of arid terrain in northeast Ethiopia, southern Eritrea, and northwestern Djibouti. The area is known for its volcanoes and extreme heat, with daily temperatures over 45 °C and often surpassing 50 °C. It has a number of lakes formed by lava flows that dammed up several valleys. Among are Lake Asale (116 m below sea level) and Lake Giuletti/Afrera (80 m below sea level), both of which possess cryptodepressions in the Danakil Depression. The Afrera contains many active volcanoes, including the Maraho, Dabbahu, Afdera and Erta Ale.[80][81]

In Somalia, there is not much seasonal variation in climate. Hot conditions prevail year-round along with periodic monsoon winds and irregular rainfall. Mean daily maximum temperatures range from 28 to 43 °C (82 to 109 °F), except at higher elevations along the eastern seaboard, where the effects of a cold offshore current can be felt. Somalia has only two permanent rivers, the Jubba and the Shabele, both of which begin in the Ethiopian Highlands.[82]

Ecology

_female.jpg)

About 220 mammals are found in the Horn of Africa. Among threatened species of the region, there are several antelopes such as the beira, the dibatag, the silver dikdik and the Speke's gazelle. Other remarkable species include the Somali wild ass, the desert warthog, the hamadryas baboon, the Somali pygmy gerbil, the ammodile, and the Speke's pectinator. The Grevy's zebra is the unique wild equid of the region. There are predators such as spotted hyena, striped hyena and African leopard. The endangered painted hunting dog had populations in the Horn of Africa, but pressures from human exploitation of habitat along with warfare have reduced or extirpated this canid in this region.[83]

Some important bird species of the Horn are the black boubou, the golden-winged grosbeak, the Warsangli linnet, and the Djibouti francolin.

The Horn of Africa holds more endemic reptiles than any other region in Africa, with over 285 species total and about 90 species which are found exclusively in the region. Among endemic reptile genera, there are Haackgreerius, Haemodracon, Ditypophis, Pachycalamus and Aeluroglena. Half of these genera are uniquely found on Socotra. Unlike reptiles, amphibians are poorly represented in the region.

There are about 100 species of freshwater fish in the Horn of Africa, about 10 of which are endemic. Among the endemic, the cave-dwelling Somali blind barb and the Somali cavefish can be found.

It is estimated that about 5,000 species of vascular plants are found in the Horn, about half of which are endemic. Endemism is most developed in Socotra and northern Somalia. The region has two endemic plant families: the Barbeyaceae and the Dirachmaceae. Among the other remarkable species, there are the cucumber tree found only on Socotra (Dendrosicyos socotrana), the Bankoualé palm, the yeheb nut, and the Somali cyclamen.

Due to the Horn of Africa's semi-arid and arid climate, droughts are not uncommon. They are complicated by climate change and changes in agricultural practices. For centuries, the region's pastoral groups have observed careful rangeland management practices to mitigate the effects of drought, such as avoiding overgrazing or setting aside land only for young or ill animals. However, population growth has put pressure on limited land and led to these practices no longer being maintained. Droughts in 1983–85, 1991–92, 1998–99 and 2011 have disrupted periods of gradual growth in herd numbers, leading to a decrease of between 37% and 62% of the cattle population. Initiatives by ECHO and USAID have succeeded in reclaiming hundreds of hectares of pastureland through rangeland management, leading to the establishment of the Dikale Rangeland in 2004.[84]

Ethnicity and languages

Besides sharing similar geographic endowments, the countries of the Horn of Africa are, for the most part, linguistically and ethnically linked together,[5] evincing a complex pattern of interrelationships among the various groups.[85]

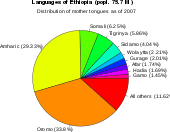

According to Ethnologue, there are 10 individual languages spoken in Djibouti, 14 in Eritrea, 90 in Ethiopia, and 15 in Somalia.[86] Most people in the Horn speak Afroasiatic languages of the Cushitic or Semitic branches. The former includes Oromo, spoken by the Oromo people in Ethiopia, and Somali, spoken by the Somali people in Somalia, Djibouti and Ethiopia; the latter includes Amharic, spoken by the Amhara people of Ethiopia, and Tigrinya spoken by the Tigrayan people of Eritrea and Ethiopia. Other Afroasiatic languages with a significant number of speakers include the Cushitic Afar, Saho, Hadiyya, Sidamo and Agaw languages, as well as the Semitic Tigre, Arabic, Gurage, Harari, Silt'e and Argobba tongues.[87]

Additionally, Omotic languages are spoken by Omotic communities inhabiting Ethiopia's southern regions. Among these idioms are Aari, Dizi, Gamo, Kafa, Hamer and Wolaytta.[88]

Languages belonging to the Nilo-Saharan and Niger-Congo families are also spoken in some areas by Nilotic and Bantu ethnic minorities, respectively. These tongues include the Nilo-Saharan Me'en and Mursi languages used in southwestern Ethiopia, and Kunama and Nara idioms spoken in parts of southern Eritrea. In the riverine and littoral areas of southern Somalia, Bajuni, Barawani, and Bantu groups also speak variants of the Niger-Congo Swahili and Mushunguli languages.[89][90]

Culture

The countries of the Horn of Africa have been the birthplace of many ancient, as well as modern, cultural achievements in several fields including agriculture, architecture, art, cuisine, education, literature, music, technology and theology to name but a few.

Ethiopian agriculture established the earliest known use of the seed grass Teff (Poa abyssinica) between 4000–1000 BCE.[91] Teff is used to make the flat bread injera/taita. Coffee also originated in Ethiopia and has since spread to become a worldwide beverage.[92] Ethiopian art is renowned for the ancient tradition of Ethiopian Orthodox Christian iconography stretching back to wall paintings of the 7th century CE.[93] Somali architecture includes the Fakr ad-Din Mosque, which was built in 1269 by the Fakr ad-Din, the first Sultan of the Sultanate of Mogadishu.[94] Ethiopia, too is renowned for its ancient churches, such as at the UNESCO World Heritage Site at Lalibela.[95]

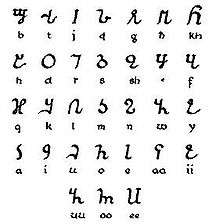

The Horn has produced numerous indigenous writing systems. Among these is Ge'ez script (ግዕዝ Gəʿəz) (also known as Ethiopic), which has been written in for at least 2000 years.[96] It is an abugida script that was originally developed to write the Ge'ez language. In speech communities that use it, such as the Amharic and Tigrinya, the script is called fidäl (ፊደል), which means "script" or "alphabet".

In the early 20th century, in response to a national campaign to settle on a writing script for the Somali language (which had long since lost its ancient script[97]), Osman Yusuf Kenadid, a Somali poet and remote cousin of the Sultan Yusuf Ali Kenadid of the Sultanate of Hobyo, devised a phonetically sophisticated alphabet called Osmanya (also known as far soomaali; Osmanya: 𐒍𐒖𐒇 𐒈𐒝𐒑𐒛𐒐𐒘) for representing the sounds of Somali.[98] Though no longer the official writing script in Somalia, the Osmanya script is available in the Unicode range 10480-104AF [from U+10480 – U+104AF (66688–66735)].

The Somali writer Nuruddin Farah has also garnered acclaim as perhaps the most celebrated writer ever to come out of the Horn of Africa. Having published many short stories, novels and essays, Farah's prose has earned him, among other accolades, the Premio Cavour in Italy, the Kurt Tucholsky Prize in Sweden, and in 1998, the prestigious Neustadt International Prize for Literature. In the same year, the French edition of his novel Gifts also won the St. Malo Literature Festival's prize.[99]

The music of the Ethiopian highlands uses a unique modal system called qenet, of which there are four main modes: tezeta, bati, ambassel, and anchihoy.[100] Three additional modes are variations on the above: tezeta minor, bati major, and bati minor.[101] Some songs take the name of their qenet, such as tezeta, a song of reminiscence.[100]

In the field of technology, the Great Stele of Axum, at over 100 feet (30 m) long, was the largest single stone ever quarried in the ancient world.[102]

Additionally, the glossy lifestyle magazine Sheeko is published quarterly for and by the Horn community.

Religion

Most inhabitants in the Horn of Africa follow one of the three major Abrahamic faiths. These religions have had a longstanding adherence in the region.

The ancient Axumite Kingdom produced coins and stelae associated with the disc and crescent symbols of the deity Ashtar.[103] The kingdom later became one of the earliest states to adopt Christianity, following the conversion of King Ezana II in the 4th century.

Islam was introduced to the northern Somali coast early on from the Arabian peninsula, shortly after the hijra. Zeila's two-mihrab Masjid al-Qiblatayn dates to the 7th century, and is the oldest mosque in Africa.[104][105] In the late 9th century, Al-Yaqubi wrote that Muslims were living along the northern Somali seaboard.[106] He also mentioned that the Adal kingdom had its capital in the city,[106][107] suggesting that the Adal Sultanate with Zeila as its headquarters dates back to at least the 9th or 10th century. According to I.M. Lewis, the polity was governed by local Somali dynasties, who also ruled over the similarly-established Sultanate of Mogadishu in the littoral Benadir region to the south. Adal's history from this founding period forth would be characterized by a succession of battles with neighbouring Abyssinia.[107]

Islam was introduced to the region early on from the Arabian peninsula, shortly after the hijra. At Muhammad's urging, a band of persecuted Muslims had fled across the Red Sea into the Horn. There, the Muslims were granted protection by the Aksumite King Aṣḥama ibn Abjar.[108]

Additionally, Judaism has a long presence in the region. The Kebra Negast ("Book of the Glory of Kings") relates that Israelite tribes arrived in Ethiopia with Menelik I, purported to be the son of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba (Makeda). The legend relates that Menelik as an adult returned to his father in Jerusalem, and then resettled in Ethiopia, and that he took with him the Ark of the Covenant.[109] The Beta Israel today primarily follow the Orit (from Aramaic "Oraita" – "Torah"), which consists of the Five Books of Moses and the books Joshua, Judges and Ruth.

A number of ethnic minority groups in southern Ethiopia also adhere to various traditional faiths. Among these belief systems are the Nilo-Saharan Surma people's acknowledgment of the sky god Tumu.[110]

Sports

In the modern era, the Horn of Africa has produced several world-famous sports personalities, including long distance runners such as the world-record holder Kenenisa Bekele and Derartu Tulu, the first Ethiopian woman to win an Olympic gold medal and the only woman to have twice won the 10,000 meter Olympic gold in the short history of the event. One of the most successful runners from the region has been Haile Gebrselassie[111] who was acclaimed as "Athlete of the Year 1998" by the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF). As well as numerous gold medals in various events, Gebrselassie achieved 15 world records and world bests in long and middle distance running, including world record marathon times in 2007 and 2008. Somali athlete Abdi Bile became a world champion when he won the 1500m for men at the 1987 World Championships in Athletics, running the final 800m of the race in 1:46.0, the fastest final 800m of any 1,500 meter track race in history.

Eritrea has established the cycling event the Tour of Eritrea.

In recent years, the Somali diaspora produced a football star in Ayub Daud, a midfielder who plays for Juventus in Italy's Serie A. Zahra Bani, a Somali-Italian javelin thrower, has garnered attention with her performances that so far have earned her adopted Italy a silver medal at the 2005 Mediterranean Games, as has Mo Farah, a Somali-British athlete that took gold for his adopted Great Britain in the 3000m at the 2009 European Indoor Championships in Turin and later golds in both the 10,000m and 5,000m at the 2012 London Olympics.

Economy

According to the IMF, in 2010 the Horn of Africa region had a total GDP (PPP) of $106.224 billion and nominal of $35.819 billion. Per capita, the GDP in 2010 was $1061 (PPP) and $358 (nominal).[112][113][114][115]

States of the region depend largely on a few key exports:

- Economy of Ethiopia: Coffee 80% of total exports.

- Economy of Somalia: Bananas and livestock over 50% of total exports.

Over 95% of cross-border trade within the region is unofficial and undocumented, carried out by pastoralists trading livestock.[116] The unofficial trade of live cattle, camels, sheep and goats from Ethiopia sold to other countries in the Horn and the wider Eastern Africa region, including Somalia and Djibouti, generates an estimated total value of between US$250 and US$300 million annually (100 times more than the official figure).[116] This trade helps lower food prices, increase food security, relieve border tensions and promote regional integration.[116] However, there are also risks as the unregulated and undocumented nature of this trade runs risks, such as allow disease to spread more easily across national borders. Furthermore, governments are unhappy with lost tax revenue and foreign exchange revenues.[116]

Much of the Horn nations' trade links are with Middle Eastern countries. In 2011, an event hosted by the Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies in Doha, Qatar devoted several days of discussion to ways in which countries in the Horn region and the adjacent Arabian peninsula could further strengthen these historically close economic, social, cultural and religious ties.[117]

See also

National history:

Sultanates and kingdoms:

- Ajuran Empire

- Adal Sultanate

- Aksumite Empire

- Ethiopian Empire

- Aussa Sultanate

- Dervish State

- Harar Sultanate

- Ifat Sultanate

- Kingdom of Gomma

- Kingdom of Gumma

- Kingdom of Jimma

- Kingdom of Kaffa

- Macrobians

- Majeerteen Sultanate

- Mudaito Dynasty

- Punt

- Sultanate of Hobyo

- Sultanate of Mogadishu

- Sultanate of Shewa

- Sultanate of the Geledi

- Walashma dynasty

- Warsangali Sultanate

- Zagwe dynasty

Notes

- ↑ "United Nations - Geographical Regions" (PDF).

- ↑ Robert Stock, Africa South of the Sahara, Second Edition: A Geographical Interpretation, (The Guilford Press: 2004), p. 26

- ↑ Michael Hodd, East Africa Handbook, 7th Edition, (Passport Books: 2002), p. 21: "To the north are the countries of the Horn of Africa comprising Ethiopia, Eritrea, Djibouti Somaliland and Somalia."

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica, inc, Jacob E. Safra, The New Encyclopædia Britannica, (Encyclopædia Britannica: 2002), p.61: "The northern mountainous area, known as the Horn of Africa, comprises Djibouti, Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Somalia."

- 1 2 Sandra Fullerton Joireman, Institutional Change in the Horn of Africa, (Universal-Publishers: 1997), p.1: "The Horn of Africa encompasses the countries of Ethiopia, Eritrea, Djibouti and Somalia. These countries share similar peoples, languages, and geographical endowments."

- ↑ J. D. Fage, Roland Oliver, Roland Anthony Oliver, The Cambridge History of Africa, (Cambridge University Press: 1977), p.190

- ↑ George Wynn Brereton Huntingford, Agatharchides, The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea: With Some Extracts from Agatharkhidēs "On the Erythraean Sea", (Hakluyt Society: 1980), p.83

- ↑ John I. Saeed, Somali – Volume 10 of London Oriental and African language library, (J. Benjamins: 1999), p. 250.

- ↑ Ciise, Jaamac Cumar. Taariikhdii daraawiishta iyo Sayid Maxamad Cabdille Xasan, 1895-1920. JC Ciise, 2005.

- ↑ Lyons, Terrence. Avoiding conflict in the Horn of Africa: US policy toward Ethiopia and Eritrea. No. 21. Council on Foreign Relations Press, 2006.

- ↑ Teklehaimanot, Hailay Kidu. "A Mobile Based Tigrigna Language Learning Tool." International Journal of Interactive Mobile Technologies (iJIM) 9.2 (2015): 50-53.

- ↑ Schreck, Carl J., and Fredrick HM Semazzi. "Variability of the recent climate of eastern Africa." International Journal of Climatology 24.6 (2004): 681-701.

- ↑ Middle East Annual Review, page 213, 1974

- ↑ Walter RC, Buffler RT, Bruggemann JH, et al. (May 2000). "Early human occupation of the Red Sea coast of Eritrea during the last interglacial". Nature. 405 (6782): 65–9. Bibcode:2000Natur.405...65W. doi:10.1038/35011048. PMID 10811218.

- ↑ Ghirotto S; Penso-Dolfin L; Barbujani G. (Aug 2011). "Genomic evidence for an African expansion of anatomically modern humans by a Southern route". Human Biology. 83 (4): 477–89. doi:10.3378/027.083.0403. PMID 21846205.

Data on cranial morphology have been interpreted as suggesting that, before the main expansion from Africa through the Near East, anatomically modern humans may also have taken a Southern route from the Horn of Africa through the Arabian peninsula to India, Melanesia and Australia, about 100,000 yrs ago.

- ↑ Mellars, P; KC, Gori; M, Carr; PA, Soares; Richards, MB (Jun 2013). "Genetic and archaeological perspectives on the initial modern human colonization of southern Asia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 110: 26. PMID 23754394.

These data support a coastally oriented dispersal of modern humans from eastern Africa to southern Asia ∼60-50 thousand years ago (ka). This was associated with distinctively African microlithic and "backed-segment" technologies analogous to the African "Howiesons Poort" and related technologies, together with a range of distinctively "modern" cultural and symbolic features (highly shaped bone tools, personal ornaments, abstract artistic motifs, microblade technology, etc.), similar to those that accompanied the replacement of "archaic" Neanderthal by anatomically modern human populations in other regions of western Eurasia at a broadly similar date.

- ↑ Lev A. Zhivotovsky, Noah A. Rosenberg & Marcus W. Feldman (2003). "Features of evolution and expansion of modern humans, inferred from genomewide microsatellite markers" (PDF). American Journal of Human Genetics. 72 (5): 1171–1186. doi:10.1086/375120. PMC 1180270. PMID 12690579. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-04-06.

- ↑ Stix, Gary (2008). "The Migration History of Humans: DNA Study Traces Human Origins Across the Continents".

- ↑ Zarins, Juris (1990), "Early Pastoral Nomadism and the Settlement of Lower Mesopotamia", (Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research)

- ↑ Diamond, J; Bellwood, P (2003). "Farmers and Their Languages: The First Expansions". Science. 300 (5619): 597–603. Bibcode:2003Sci...300..597D. doi:10.1126/science.1078208. PMID 12714734.

- ↑ Blench, R. (2006). Archaeology, Language, and the African Past. Rowman Altamira. pp. 143–144. ISBN 0759104662. Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- ↑ Jason A. Hodgson; Connie J. Mulligan; Ali Al-Meeri; Ryan L. Raaum (June 12, 2014). "Early Back-to-Africa Migration into the Horn of Africa". PLOS Genetics. 10 (6): e1004393. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004393. PMC 4055572. PMID 24921250. ; "Supplementary Text S1: Affinities of the Ethio-Somali ancestry component". doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004393.s017. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ↑ Simson Najovits, Egypt, trunk of the tree, Volume 2, (Algora Publishing: 2004), p.258.

- ↑ Pankhurst, Richard K.P. Addis Tribune, "Let's Look Across the Red Sea I", January 17, 2003 (archive.org mirror copy)

- ↑ Phoenicia, pg. 199.

- ↑ Rose, Jeanne, and John Hulburd, The Aromatherapy Book, p. 94.

- ↑ Vine, Peter, Oman in History, p. 324.

- ↑ David D. Laitin, Said S. Samatar, Somalia: Nation in Search of a State, (Westview Press: 1987), p. 15.

- ↑ I.M. Lewis, A modern history of Somalia: nation and state in the Horn of Africa, 2nd edition, revised, illustrated, (Westview Press: 1988), p.20

- ↑ Brons, Maria (2003), Society, Security, Sovereignty and the State in Somalia: From Statelessness to Statelessness?, p. 116.

- ↑ Morgan, W. T. W. (1969), East Africa: Its Peoples and Resources, p. 18.

- ↑ Nehemia Levtzion; Randall Pouwels (2000). The History of Islam in Africa. Ohio University Press. p. 228. ISBN 978-0-8214-4461-0.

- ↑ Shaping of Somali Society pg 101

- ↑ Horn and Crescent: Cultural Change and Traditional Islam on the East African Coast, 800–1900 (African Studies) by Pouwels, Randall L.. pg 15

- ↑ Ian Mortimer, The Fears of Henry IV (2007), p. 111

- ↑ Beshah & Aregay (1964), pp. 13–14.

- ↑ Beshah & Aregay (1964), p. 25.

- ↑ Beshah & Aregay (1964), pp. 45–52.

- ↑ Beshah & Aregay (1964), pp. 91, 97–104.

- ↑ Beshah & Aregay (1964), p. 105.

- ↑ van Donzel, Emeri, "Fasilädäs" in Siegbert Uhlig, ed., Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: D-Ha (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2005), p. 500.

- ↑ Pankhurst, Richard, The Ethiopian Royal Chronicles, (London:Oxford University Press, 1967), pp. 139–43.

- ↑ Horn of Africa, Volume 15, Issues 1–4, (Horn of Africa Journal: 1997), p.130.

- ↑ Michigan State University. African Studies Center, Northeast African studies, Volumes 11–12, (Michigan State University Press: 1989), p.32.

- ↑ Istituto italo-africano, Africa: rivista trimestrale di studi e documentazione, Volume 56, (Edizioni africane: 2001), p.591.

- ↑ Helen Chapin Metz, Somalia: a country study, (The Division: 1993), p.10.

- ↑ Tesfagiorgis, Gebre Hiwet (1993). Emergent Eritrea: challenges of economic development. The Red Sea Press. p. 111. ISBN 0-932415-91-1.

- ↑ Regions of Eritrea (accessed Nov 17, 2009)

- ↑ "Eritrea – The spreading revolution". Encyclopædia Britannica Article. Retrieved 2007-10-16.

- ↑ Eritrea orders Westerners in UN mission out in 10 days. International Herald Tribune. 7 December 2005

- ↑ Raph Uwechue, Africa year book and who's who, (Africa Journal Ltd.: 1977), p.209.

- ↑ Hugh Chisholm (ed.), The encyclopædia britannica: a dictionary of arts, sciences, literature and general information, Volume 25, (At the University press: 1911), p.383.

- ↑ A Political Chronology of Africa, (Taylor & Francis), p.132.

- 1 2 3 Barrington, Lowell, After Independence: Making and Protecting the Nation in Postcolonial and Postcommunist States, (University of Michigan Press: 2006), p.115

- ↑ Shillington (2005), p. 360.

- ↑ Shillington (2005), p. 1406.

- ↑ I.M. Lewis, The modern history of Somaliland: from nation to state, (Weidenfeld & Nicolson: 1965), p. 78

- ↑ Thomas P. Ofcansky, Historical dictionary of Ethiopia, (The Scarecrow Press, Inc.: 2004), p.405

- ↑ Samatar, Said Sheikh (1982). Oral Poetry and Somali Nationalism. Cambridge University Press. pp. 131 & 135. ISBN 0-521-23833-1.

- ↑ Greystone Press Staff, The Illustrated Library of The World and Its Peoples: Africa, North and East, (Greystone Press: 1967), p.338.

- ↑ Benjamin Frankel, The Cold War, 1945–1991: Leaders and other important figures in the Soviet Union, Eastern Europe, China, and the Third World, (Gale Research: 1992), p.306.

- ↑ Oihe Yang, Africa South of the Sahara 2001, 30th Ed., (Taylor and Francis: 2000), p.1025.

- ↑ Lacey, Marc (2006-06-05). "The Signs Say Somaliland, but the World Says Somalia". New York Times. Retrieved 2010-02-02.

- ↑ "Somalia". World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. 2009-05-14. Retrieved 2009-05-31.

- 1 2 "Somalia: UN Envoy Says Inauguration of New Parliament in Somalia 'Historic Moment'". Forum on China-Africa Cooperation. 21 August 2012. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ↑ "Guidebook to the Somali Draft Provisional Constitution". Archived from the original on 14 August 2013. Retrieved 2 August 2012.

- 1 2 John Young. "Regionalism and Democracy in Ethiopia" Third World Quarterly, Vol. 19, No. 2 (June 1998) pp. 192

- ↑ the people subjugated and incorporated were the Oromo, Sidama, Gurage, Wolayta and other groups. International Crisis Group. "Ethiopia: Ethnic Federalism and its Discontents" Africa Report No. 153, (4 September 2009) pp. 2

- ↑ Great Britain and Ethiopia 1897–1910: Competition for Empire Edward C. Keefer, International Journal of African Studies Vol. 6 No. 3 (1973) page 470

- ↑ Negash (2005), pp. 13–14.

- 1 2 Negash (2005), p. 14.

- ↑ Negash (2005), p. 14, and ICG "Ethnic Federalism and its Discontents" pp 2; Italy lost over 4.600 nationals in this battle.

- ↑ Clapham, Christopher, "Ḫaylä Śəllase" in Siegbert von Uhlig, ed., Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: D-Ha (Wiesbaden:Harrassowitz Verlag, 2005), pp. 1062–3.

- ↑ Monday, Jan. 06, 1936 (1936-01-06). "Man of the Year". TIME. Retrieved 2009-03-16.

- ↑ Clapham, "Ḫaylä Śəllase", Encyclopaedia Aethiopica, p. 1063.

- ↑ Dagne, Haile Gabriel (2006). The commitment of the German Democratic Republic in Ethiopia: a study based on Ethiopian sources. Münster, London: Lit; Global. ISBN 978-3-8258-9535-8.

- ↑ "Core Principles of Ethiopia's Foreign Policy: Ethiopia-Yemen relations". Ethioembassy.org.uk. Retrieved 2013-07-25.

- ↑ "2007 Annual Report" (PDF). Range Resources. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

- ↑ "Oil and Gas Exploration and Production - Playing a Better Hand" (PDF). Range Resources. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

- ↑ Marco Stoppato, Alfredo Bini (2003). Deserts. Firefly Books. pp. 160–163. ISBN 1552976696. Retrieved 17 September 2014.

- ↑ Facts On File, Incorporated (2009). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Africa and the Middle East. Infobase Publishing. p. 7. ISBN 143812676X. Retrieved 17 September 2014.

- ↑ Hadden, Robert Lee. 2007. "The Geology of Somalia: A Selected Bibliography of Somalian Geology, Geography and Earth Science." Engineer Research and Development Laboratories, Topographic Engineering Center

- ↑ info@globaltwitcher.com (2009-01-31). "Painted Hunting Dog: Lycaon pictus, GlobalTwitcher.com, ed. N. Stromberg". Globaltwitcher.auderis.se. Archived from the original on 2010-12-09. Retrieved 2013-07-25.

- ↑ Sara Pantuliano and Sara Pavanello (2009) Taking drought into account Addressing chronic vulnerability among pastoralists in the Horn of Africa Archived 2012-03-07 at the Wayback Machine. Overseas Development Institute

- ↑ Katsuyoshi Fukui; John Markakis (1994). Ethnicity & Conflict in the Horn of Africa. James Currey Publishers. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-85255-225-4.

- ↑ "Languages – Summary by country". Ethnologue.com. 1999-02-19. Retrieved 2013-07-25.

- ↑ "Languages of Ethiopia". Ethnologue. SIL International. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- ↑ "Country Level". 2007 Population and Housing Census of Ethiopia. CSA. 13 July 2010. Archived from the original on 14 November 2010. Retrieved 18 January 2013.

- ↑ "Ethnologue – Mushungulu". Ethnologue.com. 1999-02-19. Retrieved 2013-07-25.

- ↑ Abdullahi, Mohamed Diriye (2001). Culture and customs of Somalia. Greenwood. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-313-31333-2.

- ↑ David B. Grigg (1974). The Agricultural Systems of the World. C.U.P. p. 66. ISBN 9780521098434. Retrieved 2013-07-25.

- ↑ Engels, J. M. M.; Hawkes, J. G.; Worede, M. (21 March 1991). "Plant Genetic Resources of Ethiopia". Cambridge University Press – via Google Books.

- ↑ Gary Vikan. Ethiopian Icons by Stansilaw Chojnacki p.20 (2000, Skira)(accessed 22 April 2009). Skira. ISBN 978-8881186464.

- ↑ "at archnet.org (accessed 22 April 2009)". Archnet.org. 2006-02-01. Archived from the original on 4 November 2012. Retrieved 2013-07-25.

- ↑ David Buxton, The Abyssinians (New York: Praeger, 1970), p. 110

- ↑ Rodolfo Fattovich, "Akkälä Guzay" in Uhlig, Siegbert, ed. Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: A-C. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz KG, 2003, p. 169.

- ↑ Ministry of Information and National Guidance, Somalia, The writing of the Somali language, (Ministry of Information and National Guidance: 1974), p.5

- ↑ Dictionary of African Biography: Abach - Brand, Volume 1. Oxford University Press. 2012. p. 357. ISBN 0195382072. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ↑ "Lettre Ulysses Award for the Art of Reportage – Nuruddin Farah". Lettre-ulysses-award.org. 2011-12-09. Retrieved 2013-07-25.

- 1 2 Shelemay, Kay Kaufman (2001). Sadie, Stanley; Tyrrell, John, eds. The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. viii (2 ed.). London: Macmillan. p. 356.

- ↑ Abatte Barihun, liner notes for the album Ras Deshen, 2005

- ↑ University of Alabama www.hp.uab.edu Archived 2009-03-31 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Roland Anthony Oliver; Brian M. Fagan (1975). Africa in the Iron Age: C.500 BC-1400 AD. Cambridge University Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-521-09900-4.

- ↑ Briggs, Phillip (2012). Somaliland. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 7. ISBN 1841623717.

- ↑ Fauvelle-Aymar, François-Xavier. "Le port de Zeyla et son arrière-pays au Moyen Âge: Investigations archéologiques et retour aux sources écrites". Livre Islam. Retrieved 23 January 2014.

- 1 2 Encyclopedia Americana, Volume 25. Americana Corporation. 1965. p. 255.

- 1 2 Lewis, I.M. (1955). Peoples of the Horn of Africa: Somali, Afar and Saho. International African Institute. p. 140.

- ↑ "A Country Study: Somalia from The Library of Congress". Lcweb2.loc.gov. Retrieved 2013-07-25.

- ↑ Budge, Queen of Sheba, Kebra Negast, chap. 61.

- ↑ Aparna Rao; Michael Bollig; Monika Böck (2007). The Practice of War: Production, Reproduction and Communication of Armed Violence. Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-1-84545-280-3.

- ↑ Athlete Profile Haile Gebrselassie. "Gebrselassie Haile page on www.iaaf.org". Iaaf.org. Retrieved 2013-07-25.

- ↑ "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". Imf.org. 2006-09-14. Retrieved 2013-07-25.

- ↑ "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". Imf.org. 2006-09-14. Retrieved 2013-07-25.

- ↑ "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". Imf.org. 2006-09-14. Retrieved 2013-07-25.

- ↑ "The World Factbook". Cia.gov. Retrieved 2013-07-25.

- 1 2 3 4 Pavanello, Sara 2010. Working across borders – Harnessing the potential of cross-border activities to improve livelihood security in the Horn of Africa drylands Archived 2010-11-12 at the Wayback Machine.. London: Overseas Development Institute

- ↑ ""Arabs and the Horn of Africa" Kicking off November 27, 2011". daho: English.dohainstitute.org. 2011-11-21. Retrieved 2013-07-31.

References

- Beshah, Girma; Aregay, Merid Wolde (1964). The Question of the Union of the Churches in Luso-Ethiopian Relations (1500–1632). Lisbon: Junta de Investigações do Ultramar and Centro de Estudos Históricos Ultramarinos.

- Negash, Tekeste (2005). Eritrea and Ethiopia: the Federal Experience. Uppsala, Sweden: Nordiska Afrikainstitutet.

- Shillington, Kevin (2005). Encyclopedia of African History. CRC Press.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Horn of Africa. |

- History of the Horn of Africa

- Horn of Africa News Agency

- "Somali Acacia-Commiphora bushlands and thickets". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund.

- Horn of Africa Biodiversity Hotspot

- African Wild Dog Conservancy's Biodiversity Hotspots Page

- CIA World Factbook: Djibouti

- CIA World Factbook: Eritrea

- CIA World Factbook: Ethiopia

- CIA World Factbook: Somalia

- A 'Child Alert' issued by UNICEF for the Horn of Africa

- Yemen Horn of Africa Link

- Horn of Africa Concerns from the Dean Peter Krogh Foreign Affairs Digital Archives

- Combined Joint Task Force – Horn of Africa official website

- CFR.org Interactive Map: Horn of Africa

- Global Governance Institute Analysis on the Horn of Africa and the EU