Circassians

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 4–8 million | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Estimated 1,000,000[1]–2,000,000[2][3]–3,000,000[4][5]–5,000,000[2][6] to 7,000,000[7] | |

| 720,000 (2010 Census)[8] | |

| 65,000[9]–180,000 | |

| 80,000[9][10][11]–120,000[12] | |

| 40,000[9][13] | |

| 34,000 | |

| 9,000[9]–25,000 | |

| 23,000 | |

| 12,000 | |

| 4,000[14][15]–5,000[16] | |

| 2,800 | |

| 1,600 | |

| 1,100 | |

| 600 (1994 Census)[17] | |

| 500[18] | |

| Languages | |

|

Circassian (West Adyghe, Kabardian Adyghe, extinct Ubykh Adyghe dialects), also Turkish, Russian, English, Arabic, Hebrew | |

| Religion | |

|

Predominantly Sunni Islam Minority Eastern Orthodoxy,[19] Catholicism[20] and Abkhazo-Circassian native faith,[21] as well as atheists[22] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Abazgi (Abkhaz, Abazin) | |

The Circassians (Russian: Черкесы Čerkesy), also known by their endonym Adyghe (Circassian: Адыгэхэр Adygekher, Russian: Ады́ги Adýgi), are a Northwest Caucasian nation[23] native to Circassia, many of whom were displaced in the course of the Russian conquest of the Caucasus in the 19th century, especially after the Russo-Circassian War in 1864. In its narrowest sense, the term "Circassian" includes the twelve Adyghe (Circassian: Адыгэ, Adyge) princedoms (three democratic and nine aristocratic); Abdzakh, Besleney, Bzhedug, Hatuqwai, Kabardian, Mamkhegh, Natukhai, Shapsug, Temirgoy, Ubykh, Yegeruqwai and Zhaney,[24] each star on the Circassian flag representing each princedom. However, due to Soviet administrative divisions, Circassians were also designated as the following: Adygeans (Adyghe in Adygea), Cherkessians (Adyghe in Karachay-Cherkessia), Kabardians (Adyghe in Kabardino-Balkaria) and Shapsugians (Adyghe in Krasnodar Krai), although all the four are essentially the same people residing in different political units.

Most Circassians are Sunni Muslim.[25] The Circassians mainly speak the Circassian languages, a Northwest Caucasian dialect continuum with three main dialects and numerous sub-dialects. Many Circassians also speak Turkish, Russian, English, Arabic and Hebrew, having been exiled by Russia to lands of the Ottoman Empire, where the majority of them today live.[26] About 800,000 Circassians remain in historical Circassia (the modern-day titular Circassian republics of Adygea, Kabardino-Balkaria and Karachay-Cherkessia as well as Krasnodar Krai and the southwestern parts of Stavropol Krai and Rostov Oblast), and others live in the Russian Federation outside these republics and krais. The 2010 Russian Census recorded 718,727 Circassians, of whom 516,826 are Kabardian, 124,835 are other Adyghe in Adygea, 73,184 are Cherkess and 3,882 Shapsug.[8]

The Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization estimated in the early 1990s that there are as many as 3.7 million "ethnic Circassian" diaspora (in over 50 countries)[27] outside the titular Circassian republics (meaning that only one in seven "ethnic Circassians" live in the homeland), and that, of these 3.7 million, more than 2 million live in Turkey,[27] 300,000 in the Levant (mostly modern-day Jordan and Syria) and Mesopotamia and 50,000 in Western Europe and the United States.

Ethnonyms

The Circassians refer to themselves as Adyghe (also transliterated as Adyga, Adyge, Adygei, Adyghe, Attéghéi). The name is believed to derive from atté "height" to signify a mountaineer or a highlander, and ghéi "sea", signifying "a people dwelling and inhabiting a mountainous country near the sea coast", or "between two seas".[28][29]

The exonym "Circassians" (/sərˈkæsiənz/ sər-KASS-ee-ənz) is occasionally applied to Adyghe and Abaza from the North Caucasus.[30] The name Circassian represents a Latinisation of Siraces, the Greek name for the region, called Shirkess by Khazars and later Cherkess, the Turkic name for the Adyghe, and originated in the 15th century with medieval Genoese merchants and travellers to Circassia.[30][31]

The Turkic peoples[32] and Russians call the Adyghe Cherkess.[33] Folk etymology usually explains the name Cherkess as "warrior cutter" or "soldier cutter", from the Turkish words çeri (soldier) and kesmek (to cut).

Despite a common self-designation and a common Russian name,[34] Soviet authorities applied four designations to Circassians:

- Kabardian, Circassians of Kabardino-Balkaria (Circassians speaking the Kabardian language,[35][36] one of two indigenous peoples of the republic.

- Cherkess (Adyghe: Шэрджэс Šărdžăs), Circassians of Karachay-Cherkessia (Circassians speaking the Cherkess, i.e. Circassian, language[35][36] one of two indigenous peoples of the republic who are mostly Besleney Kabardians. The name "Cherkess" is the Russian form of "Circassian" and was used for all Circassians before Soviet times.

- Adyghe or Adygeans, the indigenous population of the Kuban including Adygea and Krasnodar Krai.[37]

- Shapsug, the indigenous historical inhabitants of Shapsugia. They live in the Tuapse District and the Lazarevsky City District (formerly the Shapsugsky National District) of Sochi, both in Krasnodar Krai and in Adygea.

In Russian historiography the term had been used as an exonym for Russian, Ukrainian and Cossack people at least until the end of 18th century,[38][39] and Caucasian Tatar peoples (namely Terek Tatar and Kumyk[40]).

In Turkey the term nowadays used as a name for all Caucasian nations such as, such as Karachays, Ossetians, different Dagestanian diasporas and others.[41][42]

History

Origins

.jpg)

Genetically, the Adyghe have shared ancestry partially with neighboring peoples of the Caucasus, with some influence from the other regions.[43] The Circassian language, also known as the Cherkess language, including West Adyghe, Kabardian Adyghe, and Ubykh, is a member of the ancient Northwest Caucasian language family.

Archaeological findings, mainly of dolmens in Northwest Caucasus region, indicate a megalithic culture in the Northwest Caucasus.[44] Around the beginning of the 4th Millennium BCE, the North West Caucasus region and western Steppes became influenced by the Maykop culture.

Medieval period

As a result of Greek and Byzantine influence, Christianity spread throughout the Caucasus between the 3rd and 5th centuries AD.[45][46] During that period the Circassians (referred to at the time as Kassogs)[47] began to accept Christianity as a national religion, but did not abandon all elements of their indigenous religious beliefs.

From around 400 AD wave after wave of invaders began to invade the lands of the Adyghe people, who were also known as the Kasogi (or Kassogs) at the time. They were conquered first by the Bulgars (who originated on the Central Asian steppes). Outsiders sometimes confused the Adyghe people with the similarly-named Utigurs (a branch of the Bulgars), and both peoples were sometimes conflated under misnomers such as "Utige". The Bulgar state, with its capital at Phanagoria on the Taman peninsula, reached the apex of its geopolitical sway from 632 to 668, as Old Great Bulgaria (which also occupied present-day southern Ukraine).

Under pressure from the Khazars, Great Bulgaria declined quickly and collapsed, to be succeeded by the Khazar Khaganate in 668.

Following the dissolution of the Khazar state, the Adyghe people, were integrated around the end of the 1st millennium AD into the Kingdom of Alania.

Between the 10th and 13th centuries Georgia had influence on the Adyghe Circassian peoples, with many adopting Christianity.

During the 13th century the Mamluks seized power in Cairo, and as a result the Mamluk kingdom became the most influential kingdom in a far-reaching Muslim world. Some 15th century Circassian converts to Islam became Mamluks and rose through the ranks of the Mamluk dynasty to high positions, some becoming sultans in Egypt such as Qaitbay, Mamluk Sultan of Egypt 872-901 AH (1468-1496 CE). The majority of the leaders of the Burji Mamluk dynasty in Egypt (1382–1517) had Circassian origins,[48] while also including Abkhaz, Abaza, and Georgian peoples whom the Arab sultans had recruited to serve their kingdoms as a military force.

In the 17th century, under the influence of the Crimean Tatars and of the Ottoman Empire, some Circassians started to adopt Islam.

With the rise of Muhammad Ali Pasha (who ruled Egypt from 1805 to 1848), most senior Mamluks were killed by him in order to secure his rule and the remaining Mamluks fled to Sudan.

As of 2016 several thousand Adyghe reside in Egypt; in addition to the descendants of Burji Mamluks of Adyghe origin, there are many who descend from royal Circassian consorts or Ottoman pashas of Circassian origin as well as Circassian muhajirs of the 19th century. Until the rise of Gamal Abdel Nasser in Egypt in the 1950s, the Adyghe formed an élite group in the country. Besides the Adyghe, the Egyptian Abaza family (of Abazin origin) still holds to this day an élite place in Egyptian society, and constitutes Egypt's largest family. With well over 15,000 members active in all aspects of society.

Large numbers of Circassians converted to Islam from Christianity in the 17th century.[49]

In 1708, Qaplan I Giray, a Crimean khan, ordered to have 4,000 Kabardian slaves while ascending to the throne. Kabardians led by Kurgoko Atazhukin were reluctant to pay tribute to the Crimean Khan.[50]

Qaplan I Giray along with 20,000 warriors marched to Kabarday to retrieve his demands. While setting a fire camp, Crimean Tatars were attacked by 7,000 cavalry units headed by Prince Kurgoko Atazhukin in the battle of Kinzhal near Malka River. The Crimean army was destroyed in one night on 17 September 1708. Only a small group of Crimeans headed by Qaplan I Giray managed to escape.[51]

In 2013, the Institute of Russian History of the Russian Academy of Sciences recognized that the battle of Kinzhal Mountain with the paramount importance in the national history of Kabardians, Balkarians and Ossetians.[52]

The Safavid (1501–1736) and Qajar (1789–1925) dynasties saw the importing and deporting of large numbers of Circassians to Persia, where many enjoyed prestige in the harems and in the élite armies (the so-called ghulams), while many others settled and deployed as craftsmen, labourers, farmers and regular soldiers. Many members of the Safavid nobility and élite had Circassian ancestry and Circassian dignitaries, such as the kings Abbas II of Persia (reigned 1642–1666) and Suleiman I of Persia (reigned 1666–1694). While traces of Circassian settlements in Iran have lasted into the 20th century, many of the once large Circassian minority became assimilated into the local population.[53] However, significant communities of Circassians continue to live in particular cities in Iran,[54] like Tabriz and Tehran, and in the northern provinces of Gilan and Mazandaran.[55][56]

It has been estimated that the Ottoman Empire imported some 200,000 slaves—mainly Circassians—between 1800 and 1909.[57]

Russian invasion of Circassia

Between the late 18th and early-to-mid-19th centuries, the Adyghe people lost their independence as the Russian Empire gradually carried out a series of wars and campaigns. During this period, the Adyghe plight achieved a certain celebrity status in the West; but pledges of assistance were never fulfilled. After the Crimean War of 1853 to 1856, Russia turned its attention to the Caucasus in earnest. Following major territorial losses for Persia in the Caucasus in the aftermath of the Russo-Persian War (1804–1813) and the Russo-Persian War (1826–1828), forcing Persia to cede what comprises now Georgia, Dagestan, Armenia, and Azerbaijan to Imperial Russia,[58] Russia found itself able to focus most of its army on subduing the rebelling natives of the North Caucasus, starting with the peoples of Chechnya and Dagestan. In 1859 the Russians finished defeating Imam Shamil in the eastern Caucasus, and turned their attention westward. Eventually, the long-lasting Russian–Circassian War, which had begun in 1763, ended with the defeat of the Adyghe forces. Some Adyghe leaders signed loyalty oaths on 2 June 1864 (21 May, O.S.).

The conquest of the Caucasus by the Russian Empire in the 19th century during the Russian-Circassian War led to the destruction and killing of many Adyghe—towards the end of the conflict, the Russian General Nikolai Yevdokimov had the task of driving the remaining Circassian inhabitants out of the region, primarily into the Ottoman Empire. Mobile columns of Russian riflemen and Cossack cavalry carried out the task.[59][60][61]

"In a series of sweeping military campaigns lasting from 1860 to 1864... the northwest Caucasus and the Black Sea coast were virtually emptied of Muslim villagers. Columns of the displaced were marched either to the Kuban [River] plains or toward the coast for transport to the Ottoman Empire... One after another, entire Circassian tribal groups were dispersed, resettled, or killed en masse"[61]

This expulsion, along with the actions of the Russian military in acquiring Circassian land,[62] has given rise to a movement among descendants of the expelled ethnicities for international recognition that genocide was perpetrated.[63] In 1840 Karl Friedrich Neumann estimated the Circassian casualties at around one and a half million.[64] Some sources state that hundreds of thousands of others died during the exodus.[65] Several historians use the phrase "Circassian massacres"[66] for the consequences of Russian actions in the region.[67]

On 20 May 2011 the Georgian parliament voted in a 95 to 0 declaration that Russia had committed genocide when it engaged in massacres against Circassians in the 19th century.[68]

Like other ethnic minorities under Russian rule, the Adyghe who remained in the Russian Empire borders were subjected to policies of mass resettlement.

The Ottoman Empire, which ruled large parts of the area south of Russia, regarded the Adyghe warriors as courageous and well-experienced. It encouraged them to settle in various near-border settlements of the Ottoman Empire in order to strengthen the empire's borders.

According to Walter Richmond,

"Circassia was a small independent nation on the northeastern shore of the Black Sea. For no reason other than ethnic hatred, over the course of hundreds of raids the Russians drove the Circassians from their homeland and deported them to the Ottoman Empire. At least 600,000 people lost their lives to massacre, starvation, and the elements while hundreds of thousands more were forced to leave their homeland. By 1864, three-fourths of the population was annihilated, and the Circassians had become one of the first stateless peoples in modern history".[69]

Post-exile period

The Adyghes who were settled by the Ottomans in various near-border settlements across the empire, ended up living across many territories in the Middle East. At the time these belonged to the Ottoman Empire and are now located in the following countries:

- Turkey, which has the largest Adyghe population in the world. The Adyghe settled in three main regions in Turkey: Samsun, along the shores of the Black Sea; the region near the city of Ankara, the region near the city of Kayseri, and in the western part of the country near the region of Istanbul. This latter region experienced a severe earthquake in 1999. Many Adyghe played key roles in the Ottoman army and also participated in the Turkish War of Independence.

- Syria. Most of the Adyghe who immigrated to Syria settled in the Golan Heights. Prior to the Six-Day War, the Adyghe people were the majority group in the Golan Heights region—their number at that time is estimated at 30,000. The most prominent settlement in the Golan was the town of Quneitra. The total number of Circassians in Syria is estimated to be between 50,000 and 100,000.[70] In 2013, the Syrian Circassians said they were exploring returning to Circassia, as tensions between the Baath government and the opposition forces escalated. Circassians from different parts of Syria, such as Damascus, have moved back to the Golan Heights, believed to be safer. Some refugees have been reportedly killed by shelling. Circassians have been lobbying the Russian and Israeli governments to help evacuate refugees from Syria. Some visas were issued by Russia.[71]

- Israel and Palestine. The Adyghe initially settled in three places—in Kfar Kama, Rehaniya, and in the region of Hadera. Due to a malaria epidemic, the Adyghe settlement near Hadera was eventually abandoned. Though Sunni Muslim, Adyghe are seen as a loyal minority within Israel, who serve in the armed forces.[72][73][74]

Circassian Guards in Jordan

Circassian Guards in Jordan - Jordan. The Adyghe had a major role in the history of the Kingdom of Jordan.[75][76] Over the years, various Adyghe have served in distinguished roles in the kingdom of Jordan. An Adyghe has served as a prime minister (Sa'id al-Mufti), ministers (commonly at least one minister should represent the Circassians in each cabinet), high rank officers, etc., and due to their important role in the history of Jordan, Adyghe form the Hashemites honour guard at the royal palaces. They represented Jordan in the Royal Edinburgh Military Tattoo in 2010, joining other honour guards such as the Airborne Ceremonial Unit.[77][78] Jordanian Circassians have several clusterings, most notably Sweileh in Amman.

- Iraq. The Adyghe came to Iraq directly from Circassia.They settled in all parts of Iraq—from north to south—but most of all in Iraq's capital Baghdad. Many Adyghe also settled in Kerkuk, Diyala, Fallujah, and other places. Circassians played a major role in different periods throughout Iraq's history, and made great contributions to political and military institutions in the country, to the Iraqi Army in particular. Several Iraqi prime ministers have been of Circassian descent.

Culture

Adyghe society prior to the Russian invasion was highly stratified. While a few princedoms in the mountainous regions of Adygeya were fairly egalitarian, most were broken into strict castes. The highest was the caste of the "princes", followed by a caste of lesser nobility, and then commoners, serfs, and slaves. In the decades before Russian rule, two princedoms overthrew their traditional rulers and set up democratic processes, but this social experiment was cut short by the end of Adyghe independence.

Language

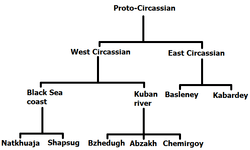

Circassians mainly speak the Circassian language, a Northwest Caucasian language with numerous dialects, the primary ones being Adyghe (West Circassian) and Kabardian (East Adyghe). West Adyghe language is based on Temirgoy dialect, while East Adyghe language is based on Kabardian dialect. Circassians also speak Russian, Turkish, English, Arabic, and Hebrew in large numbers, having been exiled by Russia to lands of the Ottoman Empire, where the majority of them live today, and some to neighboring Persia, to which they came primarily through mass deportations by the Safavids and Qajars or, to a lesser extent, as muhajirs in the 19th century.[79][80][81][82]

Walter Richmond writes that the Circassian language in Russia is "gravely threatened." He argues that Russian policy of surrounding small Circassian communities with Slavic populations has created conditions where Circassian language and nationality will disappear. By the 1990s, Russian had become the standard language for business in the Republic of Adygea, even within communities with Circassian majority populations.[83]

Religion

Ancestors of modern Adyghe people gradually went through following various religions: Monotheism with its Christianity, and then Islam.[84]

It is the tradition of the early church that Christianity made its first appearance in Circassia in the first century AD via the travels and preaching of the Apostle Andrew.[85] Subsequently, Christianity spread throughout the Caucasus between the 4th century[45] and the 6th century.[46]

A small Muslim presence in Circassia has existed since the Middle Ages, but widespread Islamization occurred after 1717, when Sultan Murad IV ordered the Crimean Khans to spread Islam among the Circassians, with the Ottomans and Crimeans seeing some success in converting members of the aristocracy who would then ultimately spread the religion to their dependents.[86] However, despite the efforts of the Ottomans and their Crimean and Circassian clients, the masses of the Circassian people remained Christian and pagan, until the threat of Russian conquest impelled the majority of them to convert in order to cement defensive alliances with the Ottoman Empire and the Crimean Khanate to protect their independence;[86][87] significant Christian and pagan presence remained among some tribes such as the Shapsugs and Natukhai with Islamization pressures implemented by those loyal to the Caucasus Emirate.[88] Sufi orders including the Qadiri and Nakshbandi orders gained prominence and played a role in spreading Islam.[22]

Today, a large majority of Circassians remain Muslim, with minorities of atheists[22] and Christians.[89] Atheist Circassians tend to be of the younger generation (20–35 years old), in which they were found to constitute a quarter of Circassians in Kabardino-Balkaria.[22] Among Christians, Catholicism, originally introduced along the coasts by Venetian and Genoese traders, today constitutes just under 1% of Kabardins.[20] Some Circassians are also Orthodox Christian, notably including those in Mozdok[90] and some of those Kursky district.[19] Among Muslims, Islamic observance varies widely between those who only know a few prayers with a Muslim identity that is more "cultural" than religious, to those who regularly observe all requirements.[22] Both Islam and the Habze are identified as national characteristics even by those that do not practice.[22] Today, Islam is a central part of life in many Circassian diaspora communities, such as in Israel, while in the Circassian homeland Soviet rule saw an extensive process of secularization, and there is wide influence of many social norms which contradict Islamic law, such as widespread observance of traditional pre-Islamic moral codes contradicting those of Islam, and norms like social alcohol consumption; in Israel, meanwhile, such non-Islamic social norms are not present.[89]

In the modern times, it has been reported that those who identify primarily as adherents of the native Habze faith (as opposed to another listed faith) constitute 12% of the population of Karachay-Cherkessia and 3% of the population of Kabardino-Balkaria.[91][21] There have also been reports of violence and threats against those "reviving" and diffusing the original Circassian pre-Islamic faith.[92][93] The relationship between habze and Islam varies between Circassian communities; for some, there is conflict between the two, while for others, such as in Israel, they are seen as complementary philosophies.[89]

Traditional social system

_p183_CIRCASSIAN_DANCE.jpg)

Society was organized by Adyghe khabze, or Circassian custom.[94] Many of these customs had equivalents throughout the mountains. It should be noted that the seemingly disorganized Circassians resisted the Russians just as effectively as the organized theocracy of Imam Shamil. The aristocracy was called warq. Some aristocratic families held the rank of Pshi or prince and the eldest member of this family was the Pshi-tkhamade who was the tribal chief. Below the warq was the large class to tfokotl, roughly yeomen or freemen, who had various duties to the warq. They were divided into clans of some sort. Below them were three classes approximating serfs or slaves. Of course, these Circassian social terms do not exactly match their European equivalents. Since everything was a matter custom, much depended on time, place, circumstances and personality. The three 'democratic' princedoms, Natukhai, Shapsug, and Abdzakh, managed their affairs by assemblies called Khase or larger ones called Zafes. Decisions were made by general agreement and there was no formal mechanism to enforce decisions. The democratic princedoms, who were perhaps the majority, lived mainly in the mountains where they were relatively protected from the Russians. They seem to have retained their aristocrats, but with diminished powers. In the remaining 'feudal' princedoms power was theoretically in the hands of the Pshi-tkhamade, although his power could be limited by Khases or other influential families.

In addition to the vertical relations of class there were many horizontal relations between unrelated persons. There was a strong tradition of hospitality similar to the Greek xenia. Many houses would have a kunakskaya or guest room. The duty of a host extended even to abreks or outlaws. Two men might be sworn brothers or kunaks. There were brotherhoods of unrelated individuals called tleuzh who provided each other mutual support. It was common for a child to be raised by an atalyk or foster father. Criminal law was mainly concerned with reconciling the two parties. Adyghe khabze is sometimes called adat when it is contrasted to the kind of Islamic law advocated by people like Imam Shamil.

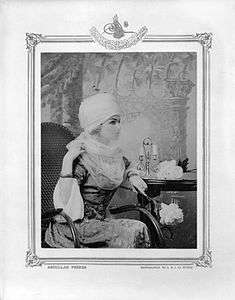

Traditional clothing

The traditional female clothing (Adyghe: Бзылъфыгъэ Шъуашэр [bzəɬfəʁa ʂʷaːʃar]) was very diverse and highly decorated and mainly depends on the region, class of family, occasions, and princedoms. The traditional female costume is composed of a dress (Adyghe: Джанэр [d͡ʒaːnar]), coat (Adyghe: Сае [saːja]), shirt, pant (Adyghe: ДжэнэкӀакор [d͡ʒanat͡ʃʼaːkʷar]), vest (Adyghe: КӀэкӀ [t͡ʃʼat͡ʃʼ]), lamb leather bra (Adyghe: Шъохътан [ʂʷaχtaːn]), a variety of hats (Adyghe: ПэӀохэр [paʔʷaxar]), shoes, and belts (Adyghe: Бгырыпхыхэр [bɣərəpxəxar]). Holiday dresses are made of expensive fabrics such as silk and velvet. The traditional colors of women's clothing rarely includes blue, green or bright-colored tones, instead mostly white, red, black and brown shades are worn. The Circassian dresses were embroidered with gold and silver threads. These embroideries were handmade and took time to complete as they were very intricate.

The traditional male costume (Adyghe: Адыгэ хъулъфыгъэ шъуашэр [aːdəɣa χʷəɬfəʁa ʂʷaːʃar]) includes a coat with wide sleeves, shirt, pants, a dagger, sword, and a variety of hats and shoes. Traditionally, young men in the warriors times wore coat with short sleeves—in order to feel more comfortable in combat. Different colors of clothing for males were strictly used to distinguish between different social classes, for example white is usually worn by princes, red by nobles, gray, brown, and black by peasants (blue, green and the other colors were rarely worn). A compulsory item in the traditional male costume is a dagger and a sword. The traditional Adyghean sword is called Shashka. It is a special kind of sabre; a very sharp, single-edged, single-handed, and guardless sword. Although the sword is used by most of Russian and Ukrainian Cossacks, the typically Adyghean form of the sabre is longer than the Cossack type, and in fact the word Shashka came from the Adyghe word "Sashkhwa" (Adyghe: Сашьхъуэ) which means "long knife". On the breast of the costume are long ornamental tubes or sticks, once filled with a single charge of gunpowder (called gaziri cartridges) and used to reload muskets.

Traditional cuisine

The Adyghe cuisine is rich with different dishes.[95][96] In the summer, the traditional dishes consumed by the Adyghe people are mainly dairy products and vegetable dishes. In the winter and spring the traditional dishes are mainly flour and meat dishes. An example of the latter is known as ficcin.

Circassian cheese is considered one of the more famous types of cheeses in the North Caucasus.

A popular traditional dish is chicken or turkey with sauce, seasoned with crushed garlic and red pepper. Mutton and beef are served boiled, usually with a seasoning of sour milk with crushed garlic and salt.

Variants of pasta are found. A type of ravioli may be encountered, which is filled with potato or beef.

On holidays the Adyghe people traditionally make Haliva (Adyghe: хьэлжъо) (fried triangular pastries with mainly Circassian cheese or potato), from toasted millet or wheat flour in syrup, baked cakes and pies. In the Levant there is a famous Circassian dish which is called Tajen Alsharkaseiah.[97]

Traditional crafts

The Adyghes have been famous for making carpets (Adyghe: пӏуаблэхэр [pʷʼaːblaxar]) or mats worldwide for thousands of years.

Making carpets was very hard work in which collecting raw materials is restricted to a specific period within the year. The raw materials were dried, and based on the intended colours, different methods of drying were applied. For example, when dried in the shade, its colour changed to a beautiful light gold colour. If it were dried in direct sun light then it would have a silver colour, and if they wanted to have a dark colour for the carpets, the raw materials were put in a pool of water and covered by poplar leaves (Adyghe: екӏэпцӏэ [jat͡ʃʼapt͡sʼa]).

The carpets were adorned with images of birds, beloved animals (horses), and plants, and the image of the Sun was widely used.

The carpets were used for different reasons due to their characteristic resistance to humidity and cold, and in retaining heat. Also, there was a tradition in Circassian homes to have two carpets hanging in the guest room, one used to hang over rifles (Adyghe: шхончымрэ [ʃxʷant͡ʃəmra]) and pistols (Adyghe: къэлаеымрэ), and the other used to hang over musical instruments.

The carpets were used to pray upon, and it was necessary for every Circassian girl to make three carpets before marriage; a big carpet, a small carpet, and the last for praying as a prayer rug. These carpets would give the grooms an impression as to the success of their brides in their homes after marriage.[98]

Tribes

From the late Middle Ages, a number of territorial- and political-based Circassian tribes or ethnic entities began to take shape. They had slightly different dialects.

Dialects came to exist after Circassia was divided into princedoms (tribes) after the death of King Yinal of Circassia, who united Circassia for the last time before its short renuion during the Russo-Caucasian War. As the logistics between the princedoms became harder, each princedom became slightly isolated from one another, thus the people living under the banner of each princedom developed their own dialects. In time, the dialects they speak were named after their princedoms. After a longer while, the people began being called after the princedom which they live under the banner of. Therefore, there is a widespread misconception of these princedoms actually being tribes. Opposed to that, the notion "tribe" is non-existent in the Circassian culture.

At the end of the Caucasian War most Circassians were expelled to the Ottoman Empire, and many of the princedoms were destroyed and the people evicted from their historical homeland in 1864.

The main groups within the Circassian people are the Adygeans, Abkhazians, Abazins, Kabardians, and Cherkess. This does not include tribal subgroups.

Most Adyghe living in Circassia are Bzhedug, Kabardian, and Temirgoy, while the majority in diaspora are Kabardian, Abdzakh, and Shapsug. West Adyghe language is based on Temirgoy dialect, while East Adyghe language is based on Kabardian dialect.

The twelve stars on the Circassian flag symbolize the individual tribes of the Circassians; the nine stars within the arc symbolize the nine aristocratic tribes of Adygea, and the three horizontal stars symbolize the three democratic tribes. The twelve tribes are the Abdzakh, Besleney, Bzhedug, Hatuqwai, Kabardian, Mamkhegh, Natukhai, Shapsug, Temirgoy, Ubykh, Yegeruqwai, and Zhaney.[99]

| Geographical designation | Main dialect | Tribe[100][101] | Circassian name | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adygeans (Adyghe of Adygea) | West Adyghe | Abzakh (Abdzakh or Abadzekh[100]) | Абдзах [aːbd͡zaːx] | Second largest Adyghe tribe in Turkey and the world, largest in Jordan, sixth largest in Russia |

| Bzhedug (Bzhedugh or Bzhedukh[100]) | Бжъэдыгъу [bʐadəʁʷ] | Third largest Adyghe tribe in Russia, lesser in other countries | ||

| Hatuqwai (Hatukay or Khatukai[100]) | Хьэтыкъуай [ħaːtəq͡χʷaːj] | Completely expelled from the Caucasus, found almost exclusively in Turkey, US, Jordan, and Israel | ||

| Mamkhegh | Мэмхэгъ, Мамхыгъ [maːmxəʁ] | a large clan, but a small tribe | ||

| Natukhai (Notkuadj[100]) | Натыхъуай [natəχʷaːj], Наткъуадж [natəχʷaːd͡ʒ] | Completely expelled from the Caucasus after the Caucasian War | ||

| Temirgoy (Chemgui or Kemgui[100]) | КIэмгуй [t͡ʃʼamɡʷəj] | Second largest Adyghe tribe in Russia, lesser in other countries | ||

| Yegeruqwai (Yegerukay) | Еджэрыкъуай [jad͡ʒarqʷaːj] | Completely expelled from the Caucasus | ||

| Zhaney (Jane or Zhan[100]) | Жанэ [ʒaːna] | Not found after the Caucasian War on a tribal basis | ||

| Shapsugs (Adyghe of Krasnodar Krai) | Shapsug (Shapsugh) | Шэпсыгъ, Шапсыгъ [ʃaːpsəʁ] | Third largest Adyghe tribe in Turkey and the world, largest in Israel | |

| Ubykhians (Adyghe of Krasnodar Krai) | Ubykh Adyghe (extinct) and Hakuchi Adyghe | Ubykh | Убых [wəbəx], Пэху | Completely expelled from the Caucasus, found almost exclusively in Turkey where most speak East Adyghe, and some West Adyghe (often Hakuchi sub-dialect) as well as Abaza |

| Kabardians (Adyghe of Kabardino-Balkaria) | Kabardian Adyghe[102] | Kabardians (Kabardinian, Kabardin, Kabarday, Kebertei, or Adyghe of Kabarda) | Къэбэрдэй [qabardaj], Къэбэртай [qabartaːj] | Largest Adyghe tribe in Turkey (over 2 millions), Russia (over 500,000), and the world (3–4 million), second or third largest in Jordan and Israel |

| Cherkessians (Cherkess or Adyghe of Karachay-Cherkessia) | Besleney[102] (Beslenei[100]) | Беслъэней [basɬənəj] |

Other Adyghe groups

Small tribes or large clans that are included in one of the twelve Adyghe tribes:

| Name | Circassian name | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Adele (Khatko) (Khetuk or Adali[100]) | ХьэтIукъу | Not found after the Caucasian War on a tribal basis, included in the Abzakh and Hatuqwai tribes |

| Ademey (Adamei or Adamiy) | Адэмый [aːdaməj] | Included in the Kabardian tribe |

| Guaye (Goaye) | Гъоайе | Not found after the Caucasian War |

| Shegak (Khegaik[100]) | Хэгъуайкъу | Not found after the Caucasian War |

| Chebsin (Čöbein[100]) | ЦIопсынэ | Not found after the Caucasian War |

| Makhosh (Mequash) (Mokhosh[100]) | Махошъ [maːxʷaʂ] | A large clan, but not enough to be a separate tribe |

The Circassian tribes can be grouped and compared in various ways. Linguists divide the Northwest Caucasian languages into Circassian (including Kabardian), Ubykh (originally an Circassian dialect, theorised to be the original form of Circassian language), and Abazgi (Abkhaz-Abaza). While Abazgi and Circassian are mutually unintelligible, Ubykh and Circassian are practically the same language. The Ubykhs lived on the Black Sea coast, around the city of Sochi, the capital of Circassia, north of Abkhazia. The Abkhazians lived on the coast between the Circassians and the Georgians, were organized as the Principality of Abkhazia and were involved with the Georgians to some degree. The Abaza, their relatives, lived north of the mountains and were involved with Circassia proper. They extended from the mountain crest northeast onto the steppe and partially separated the Kabardians from the rest. Sadz were either northern Abkhazian or eastern Abaza, depending on the source. The Kabarda occupied about a third of the north Caucasus piedmont from east of Circassia proper eastward to the Chechen country. To their north were the Nogai nomads and to the south, deeper in the mountains, were from west to east, the Karachays, Balkars, Ossetes, Ingushes, and Chechens. The Kabardians were fairly advanced, interacted with the Russians from the sixteenth century and were much reduced by plague in the early nineteenth century.

As for the Circassians proper, apparently called Kiakhs, some writers speak of twelve princedoms and some do not.

- The narrow Black Sea coast was occupied, from north to south by the Natukhai, Shapsug, Ubykh, and the Abkhaz (Sadz sub-branch). The main part of the Natukhai and Shapsug princedoms located in north of the mountains. The Natukhai were enriched by trade since their coast was not backed by high mountains and opened onto the steppe.

- The north slope was inhabited, from north to south, by the Natukhai, Shapsug, Abdzakh, and Abaza. They seem to have been the most populous princedoms after the Kabarda and its inland location gave then some protection from Nogai and Cossack raiding.

- In the far west were three small princedoms that were absorbed into the Natukhai and disappeared. These were the Adele ru:Адале on the Taman peninsula and the Shegak and Chebsin (ru:Хегайки and ru:Чебсин) near Anapa.

- Along the Kuban were the Natukhai, Zhaney, Bzhedug, Hatuqwai, and Temirgoy.

- On the east, between the Laba and Belaya, from north to south, were the Temirgoy, Yegeruqwai (ru:Егерукаевцы), Makhosh (ru:Махошевцы), Besleney and Abaza. The Besleney were a branch of the Kabardians. The Tapanta (ru:Тапанта), a branch of the Abaza, lived between the Besleney and Kabardian princedoms on the upper Kuban. Along the Belaya River were the Temirgoy, the ill-documented Ademey (ru:Адамийцы) and then the Mamkhegh near the modern Maykop.

- The Guaye (ru:Гуайе) are poorly documented. The Tchelugay lived west of the Makhosh. The Hakuch lived on the coast south of the Natukhai. Other groups are mentioned without much documentation. There are reports of princedoms migrating from one place to another, again without much documentation. Some sketch maps show a group of Karachays on the upper Laba without any explanation.

The princedoms along the Kuban and Laba rivers were exposed to Nogai and Cossack raiding while those in the interior had some protection. The three "democratic" princedoms were the Natukhai, Shapsug, and Abdzakh. They managed their affairs by assemblies while the other princedoms were controlled by "princes" or Pshi. Princedoms with remnants in the Caucasus are: Kabarda (the largest), the Temirgoy and Bzhedug in Adygea, and the Shapsug near Tuapse and to the north of Tuapsiysiy Rayon of Krasnodarskiy Kray. There are also a few Besleney and Natukhai villages, and an Abdzakh village.

Circassian diaspora

Adyghe have lived outside the Caucasus region since the Middle Ages. They were particularly well represented in the Mamluks of Turkey and Egypt. In fact, the Burji dynasty which ruled Egypt from 1382 to 1517 was founded by Adyghe Mamluks.

Starting from the 16th and 17th century up to the course of the 19th century, a massive Circassian diaspora was created in Iran and Turkey due to deportation, importation, resettlement, and to a much lesser extent voluntary migration.

Much of Adyghe culture was disrupted after the conquest of their homeland by Russia in 1864. The Circassian people were subjected to ethnic cleansing and mass exile mainly to the Ottoman Empire, and to a lesser extent Qajar Iran and the Balkans. This increased the number of Circassians in the region and even created several entirely new Circassian communities in the states that got created after the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire.

The total number of Circassians worldwide is estimated at 8 million.

Western Asia

Around half of all Circassians live in Turkey, mainly in the provinces of Samsun and Ordu (in Northern Turkey), Kahramanmaraş (in Southern Turkey), Kayseri (in Central Turkey), Bandırma, and Düzce (in Northwest Turkey).

Significant communities live in Jordan,[103] Syria (see Circassians in Syria),[103] and smaller communities live in Israel (in the villages of Kfar Kama and Rehaniya—see Circassians in Israel).[103]

Iran has a significant Circassian population.[54] It once had a very large community, but the vast amount were assimilated in the population in the course of centuries.[104][105][106] Notable places of traditional Circassian settlement in Iran include Gilan Province, Fars Province,[107] Isfahan, and Tehran (due to contemporary migration). Circassians in Iran are the nation's second largest Caucasus-derived nation after the Georgians.[54]

Circassians are also present in Iraq. Baghdad, Sulaymaniyah, and Diyala comprise the country's main cities with Circassians,[108] though lesser numbers are spread in other regions and cities as well.

Egypt

Most Circassian communities in Egypt were assimilated into the local population.[109] A prominent example is Egypt's Abaza family, a large Abazin clan.

Europe

There are Circassians in Germany and a small number in the Netherlands.

Out of 1,010 Circassians living in Ukraine (473 Kabardian Adyghe (Kabardin),[110] 338 Adygean Adyghe,[111] and 199 Cherkessian Adyghe (Cherkess)[112]—after the existing Soviet division of Circassians into three groups), only 181 (17.9%) declared fluency in the native language; 96 (9.5%) declared Ukrainian as their native language, and 697 (69%) marked "other language" as being their native language. The major Adyghe community in Ukraine is in Odessa.

There is a small community of Circassians in Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Macedonia. A number of Adyghe also settled in Bulgaria in 1864–1865 but most fled after it became separate from the Ottoman Empire in 1878. The small community that settled in Kosovo (the Kosovo Adyghes) repatriated to the Republic of Adygea in 1998.

North America

Numerous Circassians have also immigrated to the United States and settled in Upstate New York, California, and New Jersey. There is also a small Circassian community in Canada.

Sochi Olympics controversy

The 2014 Winter Olympics facilities in Sochi (once the Circassian capital)[113] were built in areas that were claimed to contain mass graves of Circassians who were killed during genocide by Russia in military campaigns lasting from 1860 to 1864.[114]

Adyghe organizations in Russia and the Adyghe diaspora around the world requested that construction at the site stop and that the Olympic Games not be held at the site of the Adyghe genocide, to prevent desecration of Adyghe graves. According to Iyad Youghar, who headed the lobby group International Circassian Council: "We want the athletes to know that if they compete here they will be skiing on the bones of our relatives."[113] The year 2014 also marked the 150th anniversary of the Circassian Genocide which angered the Circassians around the world. Many protests were held all over the world to stop the Sochi Olympics, but were not successful.

Depictions in art

A Circassian sipahi in the Ottoman Army

A Circassian sipahi in the Ottoman Army Circassian Prince Sefer Bey Zanuko in 1845

Circassian Prince Sefer Bey Zanuko in 1845_LACMA_M.87.231.42.jpg) An Adyghe man from Kabarda princedom in regular (non-traditional) wear

An Adyghe man from Kabarda princedom in regular (non-traditional) wear A painting from 1843 of an Adyghe warrior by Sir William Allan

A painting from 1843 of an Adyghe warrior by Sir William Allan- An Adyghe strike on a Russian Military Fort built over a Shapsugian village that aimed to free the Circassian Coast from the occupiers during the Russian-Circassian War, 22 March 1840

Kazbech Tuguzhoko, Circassian resistance leader

Kazbech Tuguzhoko, Circassian resistance leader The mountaineers leave the aul, P. N. Gruzinsky, 1872

The mountaineers leave the aul, P. N. Gruzinsky, 1872 A Circassian noblewoman in the 19th century

A Circassian noblewoman in the 19th century

See also

References

- ↑ Dalby, Andrew (2015). Dictionary of Languages: The Definitive Reference to More than 400 Languages. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 136. ISBN 978-1408102145.

- 1 2 Richmond, Walter (2013). The Circassian Genocide. Rutgers University Press. p. 130. ISBN 978-0813560694.

- ↑ Danver, Steven L. (2015). Native Peoples of the World: An Encyclopedia of Groups, Cultures and Contemporary Issues. Routledge. p. 528. ISBN 978-1317464006.

- ↑ Natho, Kadir I. (2009). Circassian History. Wayne, New Jersey: Xlibris Corporation. p. 505. ISBN 978-1-4415-2389-1.

- ↑ Zhemukhov, Sufian (2008). "Circassian World Responses to the New Challenges" (PDF). PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo No. 54: 2. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- ↑ Alankuş, Sevda (1999). Taymaz, Erol, ed. Kültürel-Etnik Kimlikler ve Çerkesler. Ankara, Turkey: Kafder Yayınları.

- ↑ Alankuş, Sevda; Taymaz, Erol (2009). "The Formation of a Circassian Diaspora in Turkey". Adyghe (Cherkess) in the 19th Century: Problems of War and Peace. Adygea, Russia: Maikop State Technology University. p. 2. Retrieved 4 May 2016.

Today, the largest communities of Circassians, about 5–7 million, live in Turkey, and about 200,000 Circassians live in the Middle Eastern countries (Jordan, Syria, Egypt, and Israel). The 1960s and 1970s witnessed a new wave of migration from diaspora countries to Europe and the United States. It is estimated that there are now more than 100,000 Circassian living in the European Union countries. The community in Kosovo expatriated to Adygea after the war in 1998.

- 1 2 Всероссийская перепись населения 2010: Национальньый состав населения Российской Федерации: Численность лиц, указавших соответствующую национальную принадлежность [All-Russian Population Census 2010: National composition of the population of the Russian Federation: Number of persons who indicated their ethnicity] (in Russian). Russian Federal State Statistics Service. Archived from the original (XLS) on 24 April 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 Zhemukhov, Sufian (2008). "Circassian World Responses to the New Challenges" (PDF). PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo No. 54: 2. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- ↑ "Syrian Circassians returning to Russia's Caucasus region". TRTWorld. TRTWorld and agencies. 2015. Archived from the original on 1 June 2016. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

Currently, approximately 80,000 ethnic Circassians live in Syria after their ancestors were forced out of the northern Caucasus by Russians between 1863 and 1867.

- ↑ "The Russian Presidential Council for Civil Society and Human Rights calls for the hosting of Syrian refugees in Russia". Sputniknews. 2015. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- ↑ "single | The Jamestown Foundation". Jamestown.org. 7 May 2013. Retrieved 20 August 2013.

- ↑ Lopes, Tiago André Ferreira. "The Offspring of the Arab Spring" (PDF). Strategic Outlook. Observatory for Human Security (OSH). Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- ↑ Besleney, Zeynel Abidin (2014). The Circassian Diaspora in Turkey: A Political History. Routledge. p. 96. ISBN 978-1317910046.

- ↑ Torstrick, Rebecca L. (2004). Culture and Customs of Israel. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 46. ISBN 978-0313320910.

- ↑ Louër, Laurence (2007). To be an Arab in Israel. Columbia University Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0231140683.

- ↑ Prepared by Antoniy Galabov National Report Bulgaria p. 20. Council of Europe.

- ↑ Zhemukhov, Sufian, Circassian World: Responses to the New Challenges, archived from the original on 12 October 2009

- 1 2 James Stuart Olson, ed. (1994). An Ethnohistorical dictionary of the Russian and Soviet empires. Greenwood. p. 329. ISBN 0-313-27497-5. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- 1 2 "Главная страница проекта "Арена" : Некоммерческая Исследовательская Служба СРЕДА". Sreda.org. Retrieved 20 August 2013.

- 1 2 2012 Survey Maps. "Ogonek". No 34 (5243), 27 August 2012. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Svetlana Lyagusheva. "Islam and the Traditional Moral Code of Adyghes". Iran and the Caucasus. Brill. 9 (1).

- ↑ One Europe, Many Nations: A Historical Dictionary of European National Groups. Questia Online Library. 25 August 2010. p. 12.

- ↑ Gammer, Mos%u030Ce (2004). The Caspian Region: a Re-emerging Region. London: Routledge. p. 67.

- ↑ "Главная страница проекта 'Арена' : Некоммерческая Исследовательская Служба СРЕДА". Sreda.org. Retrieved 20 August 2013.

- ↑ "International Circassian Association". Retrieved 26 April 2014.

- 1 2 Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization (1998). Mullen, Christopher A.; Ryan, J. Atticus, eds. Yearbook 1997. The Hague: Kluwer Law International. pp. 67–69. ISBN 90-411-1022-4.

- ↑ Spencer, Edmund, Travels in the Western Caucasus, including a Tour through Imeritia, Mingrelia, Turkey, Moldavia, Galicia, Silesia, and Moravia in 1836. London, H. Colburn, 1838. p. 6.

- ↑ Loewe, Louis. A Dictionary of the Circassian Language: in Two Parts: English-Circassian-Turkish, and Circassian-English-Turkish. London, Bell, 1854. p. 5.

- 1 2 Latham, R. G. Elements of Comparative Philology. London, Walton and Maberly, 1862. p. 279.

- ↑ Latham, R. G. Descriptive Ethnology. London, J. Van Voorst, 1859. p. 50.

- ↑ Guthrie, William, James Ferguson, and John Knox. A New Geographical, Historical and Commercial Grammar and Present State of the Several Kingdoms of the World... Philadelphia, Johnson & Warner, 1815. p. 549.

- ↑ Taitbout, De Marigny. Three Voyages in the Black Sea to the Coast of Circassia. London, 1837. pp. 5–6.

- ↑ S. A. Arutyunov. "Conclusion of the Russian Academy of Sciences on the ethnonym "Circassian" and the toponym "Circassia." Archived 15 February 2014 at Archive.is 25 May 2010. (in Russian)

- 1 2 Всероссийская перепись 2010, Итоги.

- 1 2 "Wayback Machine". 20 June 2013. Archived from the original on 20 June 2013. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- ↑ "Анчабадзе Ю.Д., Смирнова Я.С. Адыгейцы". Retrieved 22 February 2015.

- ↑ Радянська Енциклопедія історії України — К.: Головна редакція УРЕ, 1972. (укр.) — Т. 4. — С. 465.

- ↑ Енциклопедія українознавства (у 10 томах) / Головний редактор Володимир Кубійович. — Париж, Нью-Йорк: «Молоде Життя», 1954−1989.

- ↑ Лавров, Эпиграфические памятники Северного Кавказа. – М.: Наука, 1966. Ч.I. – 300с., стр. 202

- ↑ Tavkul, Ufuk. Karaçay-Malkar Halkına XIX. Yüzyıl Başlarına Kadar Verilen İsimler

- ↑ Aslan, Cahit (2005). Doğu Akdeniz’deki Çerkesler. Adana Kafkas Kültür Deneği Yayınları, Yayın No : 02, Temmuz-2005, Adana

- ↑ Li, Jun; Absher, Devin M.; Tang, Hua; Southwick, Audrey M.; Casto, Amanda M.; Ramachandran, Sohini; Cann, Howard M.; Barsh, Gregory S.; Feldman, Marcus; Cavalli-Sforza, Luigi L.; Myers, Richard M. (2008). "Worldwide Human Relationships Inferred from Genome-Wide Patterns of Variation". Science. 319 (5866): 1100–1104. Bibcode:2008Sci...319.1100L. doi:10.1126/science.1153717. PMID 18292342.

- ↑ "המרכז למורשת הצ'רקסית בכפר קמא". www.circassianmuseum.co.il. Archived from the original on 7 January 2013.

- 1 2 The Penny Magazine. London, Charles Knight, 1838. p. 138.

- 1 2 Minahan, James. One Europe, Many Nations: a Historical Dictionary of European National Groups. Westport, USA, Greenwood, 2000. p. 354.

- ↑ Jaimoukha, Amjad M. (2005). The Chechens: A Handbook. Psychology Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-415-32328-4. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ↑ McGregor, Andrew James (2006). A Military History of Modern Egypt: From the Ottoman Conquest to the Ramadan War. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-275-98601-8.

By the late fourteenth century Circassians from the north Caucasus region had become the majority in the Mamluk ranks.

- ↑ "Rekhaniya". Jewish Virtual Library.

- ↑ Amjad M. Jaimoukha (2014). "Circassian: Customs & Traditions" (PDF). Centre for Circassian Studies. p. 7.

- ↑ Michael Khodarkovsky (1999). "Of Christianity, Enlightenment, and Colonialism: Russia in the North Caucaus, 1550-1800" (PDF). The University of Chicago Press. p. 412.

- ↑ "РАН о Канжальской битве: "В отношении ее достоверности нет никаких сомнений" »" (in Russian). www.natpressru.info. Retrieved 2017-05-08.

- ↑ "ČARKAS". Archived from the original on 13 September 2014. Retrieved 22 February 2015.

- 1 2 3 Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Africa and the Middle East Facts On File, Incorporated ISBN 978-1438126760 p. 141

- ↑ "Circassian". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 22 February 2015.

- ↑ Waldman, Carl; Mason, Catherine (2006). "Circassians". Encyclopedia of European Peoples. 2. Infobase Publishing. pp. 175–176. ISBN 978-1-4381-2918-1. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ↑ W. G. Clarence-Smith (2006). "Islam And The Abolition Of Slavery". Oxford University Press. pp. 13–16. ISBN 0-19-522151-6

- ↑ Timothy C. Dowling Russia at War: From the Mongol Conquest to Afghanistan, Chechnya, and Beyond pp. 728–729 ABC-CLIO, 2 December 2014 ISBN 1598849484

- ↑ Levene 2005:297

- ↑ Richmond, Walter (2013). "Chapter 4". The Circassian Genocide. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-6069-4.

- 1 2 King 2008: 94–6.

- ↑ Shenfield, Stephen D., 1999. The Circassians: a forgotten genocide?. In Levene, Mark and Penny Roberts, eds., The Massacre in History. Oxford and New York, Berghahn Books. Series: War and Genocide; 1. 149–62.

- ↑ UNPO 2006.

- ↑ Neumann 1840

- ↑ Shenfield 1999

- ↑ Levene 2005:299

- ↑ Levene 2005 : 302

- ↑ Barry, Ellen (20 May 2011). "Georgia Says Russia Committed Genocide in 19th Century". The New York Times.

- ↑ Richmond, Walter (2013). The Circassian Genocide. Rutgers University Press. back cover. ISBN 978-0-8135-6069-4.

- ↑ Peleschuk, Dan (27 March 2012). "Long Lost Brethren". Russiaprofile.org. Archived from the original on 27 March 2012. Retrieved 20 August 2013.

- ↑ "single". The Jamestown Foundation. 7 May 2013. Retrieved 20 August 2013.

- ↑ "Circassians in Israel". My Jewish Learning.

- ↑ "Caucasus Foundation". www.kafkas.org.tr. Archived from the original on 14 March 2008.

- ↑ "Israel's Ethnic Communities". archive.constantcontact.com.

- ↑ "His Majesty King Abdullah II and the Circassian Elders Council 2011 (Translated)". YouTube. 5 August 2011. Retrieved 20 August 2013.

- ↑ "Jordan News Agency". Petra. Retrieved 20 August 2013.

- ↑ "Jordan at the Tattoo | Edinburgh Military Tattoo". www.edintattoo.co.uk. 5 August 2010. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- ↑ Echoes from Jordan Archived 27 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "ČARKAS". Archived from the original on 13 September 2014. Retrieved 26 April 2014.

- ↑ Oberling, Pierre, Georgians and Circassians in Iran, The Hague, 1963; pp. 127–143

- ↑ Engelbert Kaempfer (p. 204)

- ↑ Khanbaghi, Aptin, The Fire, the Star and the Cross: Minority Religions in Medieval and Early Modern Iran, p. 130

- ↑ Richmond, Walter (2013-04-09). The Circassian Genocide. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-6069-4.

- ↑ Чамокова, Сусанна Туркубиевна (2015). "ТРАНСФОРМАЦИЯ РЕЛИГИОЗНЫХ ВЗГЛЯДОВ АДЫГОВ НА ПРИМЕРЕ ОСНОВНЫХ АДЫГСКИХ КОСМОГОНИЧЕСКИХ БОЖЕСТВ". Вестник Майкопского государственного технологического университета.

- ↑ Antiquitates christianæ, or, The history of the life and death of the holy Jesus as also the lives acts and martyrdoms of his Apostles: in two parts, by Taylor, Jeremy, 1613–1667. p. 101.

- 1 2 Natho, Kadir I. Circassian History. Pages 123-124

- ↑ Shenfield, Stephen D. "The Circassians : A forgotten genocide". In Levene and Roberts, The Massacre in History. Page 150.

- ↑ Richmond, Walter. The Circassian Genocide. Page 59.

- 1 2 3 Chen Bram (1999). "CIRCASSIAN RE-IMMIGRATION TO THE CAUCASUS". In S. Weil. Routes and Roots: Emigration in a global perspective (PDF). pp. 14–15.

- ↑ Jamie Stokes, ed. (2009). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Africa and the Middle East: L to Z. Facts on File. p. 359. ISBN 0-8160-7158-6. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- ↑ Arena - Atlas of Religions and Nationalities in Russia • sreda.org

- ↑ "North Caucasus Insurgency Admits Killing Circassian Ethnographer". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 10 January 2011. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ↑ Valery Dzutsev. "High-profile Murders in Kabardino-Balkaria Underscore the Government's Inability to Control Situation in the Republic". Eurasia Daily Monitor, volume 8, issue 1, 2011. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- ↑ This section summarizes Walter Richmond, Northwest Caucasus, 2008, Chapter 2

- ↑ "Jordanian Cuisine(Bedouins, Circassians, & Palestinians)(مترجم للعربية)". YouTube. 14 January 2012. Retrieved 20 August 2013.

- ↑ Amjad Jaimoukha (ed.). "Circassian Cuisine" (PDF). Circassianworld.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 March 2012. Retrieved 20 August 2013.

- ↑ "تركى شركسية تقديم الشيف الشربينى". YouTube. 17 November 2009. Retrieved 20 August 2013.

- ↑ "Адыгэ 1оры1уатэм ухэзгъэгъозэн тхылъ", Ехъул1э Ат1ыф, Нахэхэр (129–132), гощын (1), Адыгэ ш1уш1э Хасэ, Йордания, 2009.

- ↑ "Circassians". adiga-home.net. Archived from the original on 20 August 2014. Retrieved 20 August 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "Čerkesses". E.J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam 1913–1936. Volume II. Leiden, 1987. p. 834. 9789004082656

- ↑ Культура адыгов: по свидетельствам европейских авторов. Ельбрус, 1993.

- 1 2 "Т. 4. Национальный состав и владение языками, гражданство" [T. 4. National composition and language skills, citizenship]. Итоги Всероссийской переписи населения 2010 года (Тома официальной публикации) [Results of the National Population Census 2010 (official publication of the volumes)]. Официальный сайт Госкомстата России (www.gks.ru). Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Significant numbers of Adyghe speakers reside in Turkey, Jordan, Iraq, Syria, and Israel". Languageserver.uni-graz.at. Retrieved 20 August 2013.

- ↑ "International Circassian Association". Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- ↑ Pierre, Oberling Georgians and Circassians in Iran

- ↑ "IRAN vii. NON-IRANIAN LANGUAGES (6) in Islamic Iran". Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- ↑ "ČARKAS". Archived from the original on 13 September 2014. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ↑ Katav, Ahmet Hüseyin Ali İsmail; Duman, Bilgay. "Iraqi Circassians (Chechens, Dagestanis, Adyghes)" (PDF). ORSAM Reports. Center for Middle Eastern Strategic Studiesdate=November 2012 (134). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 April 2013. Retrieved 15 April 2013.

- ↑ "Al-Gaddafi speech about the Circassians". Youtube.com. 30 July 2011. Retrieved 20 August 2013.

- ↑ "All-Ukrainian Population Census 2001: The distribution of the population by nationality and mother tongue: Kabardinians". State Statistics Committee of Ukraine. 2003. p. 3. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ↑ "All-Ukrainian Population Census: The distribution of the population by nationality and mother tongue: Adygeis". State Statistics Committee of Ukraine. 2003. p. 1. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ↑ "All-Ukrainian Population Census 2001: The distribution of the population by nationality and mother tongue: Circassians". State Statistics Committee of Ukraine. 2003. p. 7. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- 1 2 "Circassians: Home thoughts from abroad: Circassians mourn the past—and organise for the future", The Economist, dated 26 May 2012.

- ↑ Tharoor, Ishaan (6 February 2014). "Russia's Sochi Olympics Stirs Circassian Nationalism". Time. Retrieved 22 February 2015.

Further reading

- Jaimoukha, Amjad, The Circassians: A Handbook; New York, Palgrave, 2001; London, Routledge Curzon, 2001. ISBN 978-0-312-23994-7.

- Jaimoukha, Amjad, Circassian Culture and Folklore: Hospitality Traditions, Cuisine, Festivals & Music (Kabardian, Cherkess, Adigean, Shapsugh & Diaspora), Bennett and Bloom, 2010.

- Bell, James Stanislaus, Journal of a residence in Circassia during the years 1837, 1838, and 1839 .

- Richmond, Walter. The Circassian Genocide, Rutgers University Press, 2013. ISBN 978-0-8135-6069-4

- Rasizade, Alec. Book review: Let Our Fame be Great, by Oliver Bullough (London: Penguin Books, 2011, 512 pages). = Debatte: Journal of Contemporary Central and Eastern Europe (London: Taylor & Francis), December 2011, volume 19, issue 3, pages 689–692.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Circassians. |

- International Circassian Association.

- Britannica – "Circassian".

- Famous Circassians.

- Map of the diaspora.