Ashurbanipal

| Ashurbanipal Aššur-bāni-apli ܐܫܘܪ ܒܢܐ ܐܦܠܐ | |

|---|---|

|

King of Assyria, Babylonia, Akkad, Sumer, Egypt, Kush and Elam ܡܠܟܐ ܕܐܬܘܪ ܘܒܒܠ ܘܐܟܕ ܘܫܘܡܪ ܘܡܨܪܝܢ ܘܟܘܫ ܘܥܝܠܡ Malkā d-ʾĀṯūr w-Bāḇēl w-Akkad w-Šūmēr w-Miṣrēn w-Kūš w-'Īlām | |

%2C_c._645-635_BC%2C_British_Museum_(16722368932).jpg) Part of the Lion Hunt of Ashurbanipal | |

| Reign | 668 – c. 627 BC |

| Predecessor | Esarhaddon |

| Successor | Aššur-etel-ilāni |

| Born | Nineveh |

| Died |

627 BC Nineveh |

| Spouse | Libbāli-šarrat |

| Issue |

Aššur-etel-ilāni Sîn-šarru-iškun Aššur-uballiṭ II (?) |

| Dynasty | Sargonid dynasty |

| Father | Esarhaddon |

| Mother | Aššur-hammat |

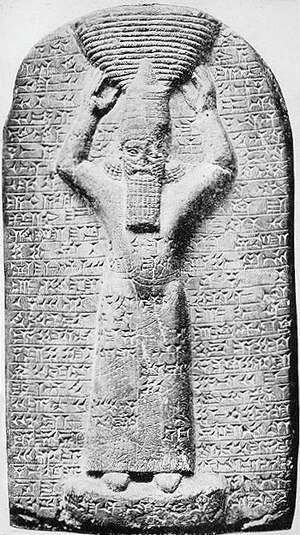

Ashurbanipal (Akkadian: Aššur-bāni-apli; Syriac: ܐܫܘܪ ܒܢܐ ܐܦܠܐ; 'Ashur is the creator of an heir'), also spelled Assurbanipal or Ashshurbanipal, was King of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 668 BC to c. 627 BC, the son of Esarhaddon and the last strong ruler of the empire, which is usually dated between 934 and 609 BC.[1] He is famed for amassing a significant collection of cuneiform documents for his royal palace at Nineveh.[2] This collection, known as the Library of Ashurbanipal, is now in the British Museum, which also holds the famous Lion Hunt of Ashurbanipal set of Assyrian palace reliefs.

In the Hebrew Bible he is called Asenappar (Hebrew: אָסְנַפַּר, Modern 'Asnapar, Tiberian 'Āsenapar - Ezra 4:10).[3] Roman historian Justinus identified him as Sardanapalus, although the fictional Sardanapalus is depicted as the last king of Assyria and an ineffectual, effete and debauched character, whereas three further kings succeeded Ashurbanipal, who was in fact an educated, efficient, highly capable and ambitious warrior king.[4]

Early life

Ashurbanipal was born toward the end of a 1,500-year period of Assyrian ascendancy.[5]

His father, Esarhaddon, the youngest son of Sennacherib, had become heir when the crown prince, Ashur-nadin-shumi, was deposed by rebels from his position as a vassal for Babylon. Esarhaddon was the son not of Sennacherib's queen, Tashmetum-sharrat, but of the "palace woman" Zakutu, "the pure" (cf. Modern Standard Arabic زكاة [zakāt], "that which purifies"), known by her native name, Naqi'a. There are some suggestions Zakutu may have been an Israelite or Aramean concubine, while others point to her family origins being in the northern Assyrian city of Harran.[6] The only queen known for Esarhaddon was Ashur-hamat, who died in 672 BC.

Ashurbanipal grew up in the small palace called Bit Reduti (house of succession), built by his grandfather Sennacherib when he was crown prince in the northern quadrant of Nineveh.[5] In 694 BC, Sennacherib had completed the "Palace Without Rival" at the southwest corner of the acropolis, obliterating most of the older structures. The "House of Succession" had become the palace of Esarhaddon, the crown prince. In this house, Ashurbanipal's grandfather was assassinated by uncles identified only from the biblical account as Adrammelech, Abimlech and Sharezer. From this conspiracy, Esarhaddon emerged as king in 681 BC. He proceeded to rebuild as his residence the Bit Masharti (weapons house, or arsenal). The "House of Succession" was left to his mother and the younger children, including Ashurbanipal.

The names of five brothers and one sister are known.[5] Sin-iddin-apli, the intended crown prince, died prior to 672 BC. Not having been expected to become heir to the throne, Ashurbanipal was trained in scholarly pursuits as well as the usual horsemanship, hunting, chariotry, soldiery, craftsmanship, and royal decorum. In a unique autobiographical statement, Ashurbanipal specified his youthful scholarly pursuits as having included oil divination, mathematics, and reading and writing; he was able to read and write in Sumerian, Akkadian and Aramaic.

Royal succession

Ashurbanipal succeeded his father Esarhaddon (reigned 681–669 BC) as king of Assyria and ruler of the Assyrian Empire in 668 BC. Esarhaddon had prepared for the accession of his son by imposing a vassal treaty upon his Persian, Median and Parthian subjects, ensuring that they accepted Ashurbanipal's dominance in advance. He had also rebuilt Babylon and set up another of his sons Shamash-shum-ukin to rule there, subject to his brother Ashurbanipal in Nineveh.

Military accomplishments

Despite being a popular king among his subjects, he was also known for his cruelty to his enemies. Some pictures depict him putting a dog chain through the jaw of a defeated Arab king and then making him live in a dog kennel.[7] Many paintings of the period exhibit his brutality; however, Assyrian harshness was reserved solely for those who took up arms against the Assyrian king, and neither Ashurbanipal nor his predecessors conducted genocides, massacres or ethnic cleansings against civilian populations.[8][9]

Ashurbanipal inherited from Esarhaddon not only the throne of the empire but also the ongoing war in Egypt with Kush/Nubia. Ashurbanipal ended Egyptian interference in the Near East, destroyed the Kushite Empire, drove the Kushites/Nubians from Egypt, and conquered Egypt and Libya. However, the Nubians still had ambitions to regain control of Egypt and resurrect their empire.

Ashurbanipal sent an army against them in 667 BC that defeated the Nubian king Taharqa, near Memphis, while Ashurbanipal stayed at his capital in Nineveh. At the same time, some Egyptian vassals rebelled and were also defeated. All of the vanquished leaders save one were sent to Nineveh. Only Necho I, the native Egyptian Prince of Sais, convinced the Assyrians of his loyalty and was sent back to become the Assyrian puppet Pharaoh of Egypt. After the death of Taharqa in 664 BC his nephew and successor Tantamani invaded Upper Egypt and took control of Thebes. In Memphis, he defeated the native Egyptian princes and Necho may have died in the battle. Ashurbanipal sent another army and again it succeeded in defeating the Kushites/Nubians. Tantamani was routed and driven back to his homeland in Nubia and was never again to threaten Assyria or Egypt. The Assyrians plundered Thebes and took much booty home with them. How Assyrian rule in Egypt ended is not certain, but at some point, Necho's son Psammetichus I gained independence while wisely keeping his relations with Assyria friendly.

An Assyrian royal inscription tells how the Lydian king Gyges received dreams from the Assyrian god Ashur. The dreams told him that when he submitted to Ashurbanipal, he would conquer his foes. After Gyges sent his ambassadors to accept Assyrian vassalage, he defeated his Cimmerian enemies. But later when he supported the rebellion of the Egyptian rebels his country was overrun by the Cilicians.[10]

Assyria was by then master of the largest empire the world had yet seen, stretching from the Caucasus in the north to North Africa and the Arabian peninsula in the south, and from Cyprus and the east Mediterranean in the west, to central Iran in the east. Ashurbanipal enjoyed the subjugation of a myriad of nations and peoples, including Babylon, Chaldea, Media, Persia, Egypt, Libya, Elam, Gutium, Parthia, Cissia, Phrygia, Mannea, Corduene, Aramea, Urartu, Lydia, Cilicia, Commagene, Caria, Cappadocia, Phoenicia, Canaan, the Suteans, Sinai, Israel, Judah, Samarra, Moab, Edom, Ammon, Nabatea, Arabia, the Neo-Hittites, Dilmun, Meluhha, Nubia, Scythia, Cimmeria, Armenia and Cyprus, with few problems during Ashurbanipal's reign. For the time being, the dual monarchy in Mesopotamia went well, with Shamash-shum-ukin accepting his position as the vassal of his brother peaceably.[11]

For his assignment of his brother, Ashurbanipal sent a statue of the divinity Marduk with him as sign of good will.[12] Shamash-shuma-ukin's power was limited. He performed Babylonian rituals, but the official building projects were still executed by his younger brother. During his first years Elam was still in peace as it was under his father. Ashurbanipal sent food supplies to the Elamites during a famine. Around 664 BC the situation changed and Urtaku, the Elamite king, attacked Assyria's colony of Babylonia by surprise. Assyria delayed in sending aid to Babylon. This could have been caused for two reasons: either the soothing messages of Elamite ambassadors or Ashurbanipal might simply not have been present at that time. However the Assyrians eventually attacked, and the Elamites retreated before the Assyrian troops, and in the same year Urtaku died. He was succeeded by Teumman (Tempti-Khumma-In-Shushinak), who was not his legitimate heir, so many Elamite princes had to flee to Ashurbanipal's court, including Urtaku's oldest son Humban-nikash. In 658/657 BC the two empires clashed again when the province of Gambulu in 664 rebelled against the Assyrians, and Ashurbanipal decided to punish them. On the other hand, Teumman saw his authority threatened by the Elamite princes at the Assyrian court and demanded their extradition. The Assyrian forces invaded Elam and fought a battle at the Ulaya river.[13]

Elam was defeated in the battle in which, according to Assyrian reliefs, Teumman committed suicide.[14] Ashurbanipal installed Humban-nikash as king of Madaktu and another prince, Tammaritu, as king of the city Hidalu. Elam was considered a vassal of Assyria and tribute was imposed on it. With the Elamite, problem solved the Assyrians could finally punish Gambulu and seized its capital. Then the victorious army marched home taking with them the head of Teumman. In Nineveh, when the Elamite ambassadors saw the head, one tore out his beard and the other committed suicide. As further humiliation, the head of the Elamite king was put on display at the port of Nineveh. The death and head of Teumman was depicted multiple times in the reliefs of Ashurbanipal's palace.[15]

Friction grew between the two brother kings, and in 652 BC Babylon rebelled. This time Babylon was not alone – it had allied itself with a host of peoples resentful of Assyrian rule, including Sutean, Chaldean and Aramean tribes dwelling in its southern regions, the kings of "Gutium", Amurru, and Meluhha, the Persians, the Arabs and Nabateans dwelling in the Arabian Peninsula, and even Elam. According to a later Aramaic tale on Papyrus 63, Shamash-shum-ukin formally declared war on Ashurbanipal in a letter where he claims that his brother is only the governor of Nineveh and his subject.[16] Again the Assyrians delayed an answer, this time due to unfavourable omens. It is not certain how the rebellion affected the Assyrian heartlands, but there was some unrest in the cities.[17] When Babylon finally was attacked, the Assyrians were victorious. Civil war prevented by further military aid, and in 648 BC Borsippa and Babylon were besieged. Without aid the situation was hopeless. After two years Shamash-shum-ukin met his end in his burning palace just before the city surrendered. This time Babylon was not destroyed, as under Sennacherib, but a massacre of the rebels took place, according to the king's inscriptions, with the Assyrians exacting savage revenge upon the Babylonians, Arameans, Chaldeans and Persians, together with an invasion of Arabia and the brutal subjugation of the Arab tribes to the south of Mesopotamia. Ashurbanipal allowed Babylon to keep its semi-autonomous position, but it became more formalized than before. The next king, Kandalanu, (an Assyrian governor) left no official inscription, probably as his function was only ritual.[18]

During the final two decades of Ashurbanipal's rule, Assyria was peaceful, and its dominance went unchallenged, but the country faced an underlying decline due to over-expansion, the lack of funds from its devastated colonies, and insufficient troops to govern its vast empire. Documentation from the last years of Ashurbanipal's reign is scarce. The last attestations of Ashurbanipal's reign are of his year 38 (631 BC), but according to the Greek historian Castor, he reigned for 42 years until 627 BC.[19]

After Ashurbanipal's death c. 627 BC he was succeeded by Ashur-etil-ilani (626–623 BC). However, Assyria soon descended into a series of internal civil wars that would ultimately lead to its downfall.

Library of Ashurbanipal

Ashurbanipal was proud of his scribal education. He asserts this in the statement: “I Assurbanipal within [the palace], took care of the wisdom of Nebo, the whole of the inscribed tablets, of all the clay tablets, the whole of their mysteries and difficulties, I solved.”[20] He was one of the few kings who could read the cuneiform script in Akkadian and Sumerian, and claimed that he even read texts from before the great flood. He was also able to solve mathematical problems. During his reign, he collected cuneiform texts from all over Mesopotamia, especially Babylonia, in his royal library at Nineveh, the Assyrian capital.[21] He commissioned copies of literary works from libraries around the kingdom in order to obtain "the hidden treasures of the scribe's knowledge."[22][23] The results were stored in what became known as the Library of Ashurbanipal.

Nineveh was destroyed in 612 BC, but many of the library's clay tablets survived the devastation. Ashurbanipal's palace was excavated in December 1853 and the surviving contents of the library re-discovered.[24] Over 30,000 clay tablets and fragments were uncovered in the library,[25] providing archaeologists with a wealth of Mesopotamian literary, religious and administrative work. The library included hymns and prayers, medical, mathematical, ritual, divinatory and astrological texts, alongside all sorts of administrative documents, letters and contracts. Other genres found during excavations included standard lists used by scribes and scholars, word lists, bilingual vocabularies, lists of signs and synonyms, lists of medical diagnoses, astronomic/astrological texts. The scribal texts proved to be very helpful in deciphering cuneiform.[21]

| |

|

|

Ashurbanipal is considered by some library scholars as an archetypal academic librarian, in that his library set the course for how the libraries of today operate.[26] While the library at Ninevah was utilized by a select elite and Ashurbanipal himself, the basic purposes of the library and the services provided are similar to those currently seen in modern academic libraries.

Art and culture

The British Museum in London has the Lion Hunt of Ashurbanipal, a set of Assyrian palace reliefs from the North Palace of Ashurbanipal, also excavated at Nineveh, depicting the king hunting and killing Mesopotamian lions.[27] In Assyria, the lion hunt was seen as a royal sport; the depictions were seen as a symbol of the king's ability to guard the nation.[28] The “Garden Party” relief shows the king and his queen having a banquet celebrating the Assyrian triumph over Tuemman in the campaign against Elam. The fine carvings serve as testimony to Ashurbanipal's high regard for art, but also communicate an important message meant to be passed down for posterity.[29]

The sculptor Fred Parhad (1947–) created a larger-than-life statue of Ashurbanipal, which was placed on a street near the San Francisco City Hall main square in 1988.[30][31] The sculpture shows Asurbanipal wearing a short tunic and holds a lion cub in his proper right arm. The figure stands on a concrete base, with bronze plaque and rosettes. The statue stands across from City Hall next to the Asian Art Museum and faces the San Francisco Library.

Robert E. Howard wrote a short story entitled "The Fire of Asshurbanipal" (sic), first published in the December 1936 issue of Weird Tales magazine, about an "accursed jewel belonging to a king of long ago, whom the Grecians called Sardanapalus and the Semitic peoples Asshurbanipal".[32]

"The Mesopotamians", a 2007 song by They Might Be Giants, mentions Ashurbanipal, along with Gilgamesh, Sargon, and Hammurabi.[33]

Ashurbanipal was used as the ruler of the Assyrians in the second expansion pack (Brave New World) for the game Civilization V.[34]

See also

References and footnotes

- ↑ These are the dates according to the Assyrian King list, Assyrian kinglist

- ↑ "Ashurbanipal - king of Assyria". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ↑ See other versions at Ezra 4:10

- ↑ Marcus Junianus Justinus. "Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus".

His successors too, following his example, gave answers to their people through their ministers. The Assyrians, who were afterwards called Syrians, held their empire thirteen hundred years. The last king that reigned over them was Sardanapalus, a man more effeminate than a woman.

- 1 2 3 Northen Magill, Frank; Christina J. Moose; Alison Aves; Taylor and Francis (1998). Dictionary of World Biography: The ancient world. pp. 141–142.

- ↑ Melville, Sarah C. (1999). The role of Naqia/Zakutu in Sargonid politics. Helsinki: Neo-Assyrian Text Corpus Project. ISBN 9514590406.

- ↑ Luckenbill, D.D. Ancient Records of Assyria and Babylonia II. p. 314.

- ↑ "It must be noted, however, that these atrocities were usually reserved for those local princes and their nobles who had revolted and that in contrast with the Israelites, for instance, who exterminated the Amalekites for purely ethnocultural reasons, the Assyrians never indulged in systematic genocides." (Georges Roux, Ancient Iraq, Third Edition, p. 291)

- ↑ They have been maligned. Certainly, they could be rough and tough to maintain order, but they were defenders of civilization, not barbarian destroyers." (H.W.F. Saggs, The Might That Was Assyria, p. 2)

- ↑ Roaf, M. Cultural atlas of Mesopotamia and the ancient near east 2004. pp. 190–191.

- ↑ Georges Roux – Ancient Iraq

- ↑ Frame, G. Babylonia 689-627. p. 104.

- ↑ This is the name according to Assyrian sources; the river is today identified with either the Karkheh or Karun.

- ↑ Banipal, Cem (1986). The War of Banipalian. Çankaya: Bilkentftp Press. pp. 31–52.

- ↑ Frame, G. Babylonia 689–627 BC. pp. 118–124.

- ↑ Steiner and Ninms, RB 92 1985

- ↑ Frame, G. Babylonia 689–627 BC. pp. 131–141.

- ↑ Oates, J. (2003). Babylon. p. 123.

- ↑ Most important examples are the Harran inscription and the Uruk king list.

- ↑ Cylinder A, Column I, Lines 31–33, in Smith, George. History of Assurbanipal, Translated from the Cuneiform Inscriptions. London: Harrison and Sons, 1871: pg.6

- 1 2 Roaf, M. (2004). Cultural Atlas of Mesopotamia and the Ancient Near East. p. 191.

- ↑ Murray, Stuart (2009). The Library: An Illustrated History. Chicago: ALA Editions.

- ↑ Coogan, Michael (2009). A Brief Introduction to the Old Testament. New York City: Oxford University Press. p. 292.

- ↑ Murray, Stuart (2009). The Library: An Illustrated History. New York, NY: Skyhorse Publishing. pp. 3–10. ISBN 9780838909911.

- ↑ https://www.britishmuseum.org/research/research_projects/ashurbanipal_library_phase_1.aspx "Assurbanipal Library Phase 1", British Museum One

- ↑ Briscoe, Peter; Bodtke-Roberts, Alice; Douglas, Nancy; Heinold, Michele; Koller, Nancy; Peirce, Roberta (1986). "Ashurbanipal' s Enduring Archetype: Thoughts on the Library's Role in the Future". College & Research Libraries: 121.

- ↑ Ashrafian, H. (2011). "An extinct Mesopotamian lion subspecies". Veterinary Heritage. 34 (2): 47–49.

- ↑ ""Assyria: Lion Hunt (Room 10a)." British Museum". Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- ↑ ""'Garden Party' relief from the North Palace of Ashurbanipal (Room S),". British Museum". Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- ↑ "Smithsonian Art Inventories Catalog – Ashurbanipal, (sculpture)". Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- ↑ "Ashurbanipal Statue at the Main San Francisco Library in San Francisco". Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- ↑ Price, R. M. (ed.): Nameless Cults: The Cthulhu Mythos Fiction of Robert E. Howard, Chaosium (2001), pp. 99–118.

- ↑ Don Nardo, Babylonian Mythology. Greenhaven Publishing LLC, 2012. ISBN 0737766476 (p.88).

- ↑ "Civ V's Brave New World expansion lets you conquer the world with trade or culture wars". Venture Beat. 12/04/2013. Retrieved 10/01/2018. Check date values in:

|access-date=, |date=(help)

Sources

- Barnett, R. D. (1976). Sculptures from the North Palace of Ashurbanipal at Nineveh (668–627). London: British Museum.

- Grayson, A. K. (1980). "The Chronology of the Reign of Ashurbanipal". Zeitschrift für Assyriologie. 70 (2): 227–245. doi:10.1515/zava.1980.70.2.227.

- Luckenbill, Daniel David (1926). Ancient Records of Assyria and Babylonia: From Sargon to the End. 2. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Murray, S. (2009). The Library: An Illustrated History. New York, NY:: Skyhorse Pub.

- Oates, J. (1965). "Assyrian Chronology, 631-612 B.C". Iraq. 27 (2): 135–159. doi:10.2307/4199788.

- Olmstead, A. T. (1923). History of Assyria. New York: Scribner.

- Russell, John Malcolm (1991). Sennacherib's Palace without Rival at Nineveh. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Further reading

- Delaunay, J. A. (1987). "AŠŠURBANIPAL". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, Fasc. 8. pp. 805–806.

- Ito, Sanae (2015). Royal Image and Political Thinking in the Letters of Assurbanipal. Ph.D. thesis. Helsinki: University of Helsinki. ISBN 978-951-51-0972-9.

- [1]

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ashurbanipal. |

- Ashurbanipal

- The Library of King Ashurbanipal Web Page

- Assurbanipal Coronation Hymn

- History Of Assurbanipal, Translated from the Cuneiform Inscriptions by George Smith

- Historical Prism Inscriptions of Ashurbanipal I: Editions E, B1–5, D, and K – Oriental Institute

| Preceded by Esarhaddon |

King of Assyria 668–c. 627 BC |

Succeeded by Ashur-etil-ilani |

- ↑ Lyons, Martyn (2011). Books: A Living History. Los Angeles: J. Paul Gerry Museum. pp. 16–17.

|access-date=requires|url=(help)