Okavango Delta

| UNESCO World Heritage site | |

|---|---|

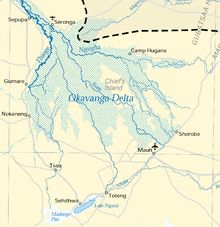

Map of the delta with basin boundary as dashed line | |

| Location | Botswana |

| Criteria | Natural: vii, ix, x |

| Reference | 1432 |

| Inscription | 2014 (38th Session) |

| Area | 2,023,590 ha |

| Buffer zone | 2,286,630 ha |

| Coordinates | 19°17′00″S 22°54′00″E / 19.28333°S 22.90000°E |

| Official name | Okavango Delta System |

| Designated | 12 September 1996 |

| Reference no. | 879[1] |

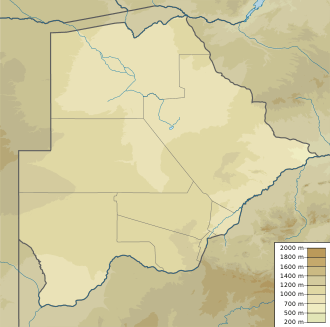

Location of Okavango Delta in Botswana | |

The Okavango Delta (or Okavango Grassland) (formerly spelled "Okovango" or "Okovanggo") in Botswana is a very large, swampy inland delta formed where the Okavango River reaches a tectonic trough in the central part of the endorheic basin of the Kalahari. All the water reaching the delta is ultimately evaporated and transpired, and does not flow into any sea or ocean. Each year, about 11 cubic kilometres (2.6 cu mi) of water spread over the 6,000–15,000 km2 (2,300–5,800 sq mi) area. Some flood waters drain into Lake Ngami.[2] The area was once part of Lake Makgadikgadi, an ancient lake that mostly dried up by the early Holocene. [3]

The Moremi Game Reserve, a National Park, is on the eastern side of the Delta. The Delta was named as one of the Seven Natural Wonders of Africa, which were officially declared on February 11, 2013, in Arusha, Tanzania.[4] On 22 June 2014, the Okavango Delta became the 1000th site to be officially inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List.[5][6]

Geography

Floods

The Okavango is produced by seasonal flooding. The Okavango River drains the summer (January–February) rainfall from the Angola highlands and the surge flows 1,200 km (750 mi) in around one month. The waters then spread over the 250 by 150 km (155 by 93 mi) area of the delta over the next four months (March–June). The high temperature of the delta causes rapid transpiration and evaporation, resulting in a cycle of rising and falling water level that was not fully understood until the early 20th century. The flood peaks between June and August, during Botswana’s dry winter months, when the delta swells to three times its permanent size, attracting animals from kilometres around and creating one of Africa’s greatest concentrations of wildlife.

The delta is very flat, with less than 2 m (6 ft 7 in) variation in height across its 15,000 km2 (5,800 sq mi).[7]

Water flow

Every year, about 11 km3 (11,000 billion l; 2.6 cu mi; 2,900 billion US gal) of water flow into the delta. Roughly 60% is consumed through transpiration by plants, 36% by evaporation, 2% percolates into the aquifer system; and 2% flows into Lake Ngami. This turgid outflow means that the delta is unable to flush out the minerals carried by the river and is liable to become increasingly salty and uninhabitable. Water salinity is reduced by salt collecting around plant roots as most of the incoming water is transpired by plants. Peat fires might contribute to deposit salt into layers below the surface. The low salinity of the water also means that the floods do not greatly enrich the floodplain with nutrients.

Salt islands

The agglomeration of salt around plant roots leads to barren white patches in the centre of many of the thousands of islands, which have become too salty to support plants, aside from the odd salt-resistant palm tree. Trees and grasses grow in the sand around the edges of the islands that have not become too salty yet.

About 70% of the islands began as termite mounds (often Macrotermes spp.), where a tree then takes root on the mound of soil.

Chief’s Island

Chief’s Island, the largest island in the delta, was formed by a fault line which uplifted an area over 70 km long (43 mi) and 15 km wide (9.3 mi). Historically, it was reserved as an exclusive hunting area for the chief. It now provides the core area for much of the resident wildlife when the waters rise.

Climate

The Delta's profuse greenery is not the result of a wet climate; rather, it is an oasis in an arid country. The average annual rainfall is 450 mm (18 in) (approximately one third that of its Angolan catchment area) and most of it falls between December and March in the form of heavy afternoon thunderstorms.

December to February are hot wet months with daytime temperatures as high as 40 °C (104 °F), warm nights, and humidity levels fluctuating between 50 and 80%. From March to May, the temperature becomes far more comfortable with a maximum of 30 °C (86 °F) during the day and mild to cool nights. The rains quickly dry up leading into the dry, cold winter months of June to August. Daytime temperatures at this time of year are mild to warm, but the temperature begins to fall after sunset. Nights can be surprisingly cold in the delta, with temperatures barely above freezing.

The September to November span has the heat and atmospheric pressure build up once more, as the dry season slides into the rainy season. October is the most challenging month for visitors - daytime temperatures often push past 40 °C (104 °F) and the dryness is only occasionally broken by a sudden cloudburst.

Wildlife

The Okavango delta is both a permanent and seasonal home to a wide variety of wildlife which is now a popular tourist attraction.[8]

Species include the African bush elephant, lion, wildebeest, hartebeest, sitatunga, springbok, common eland, kudu, duiker, steenbok, gemsbok, sable antelope, impala, roan antelope, Plains zebra, tsessebe, South African giraffe, red lechwe, African buffalo, ostrich,[9] hippopotamus,[10] black rhinoceros,[11] white rhinoceros, African wild dog, wattled crane[12] Nile crocodile,[13] cheetah,[14] African leopard, chacma baboon,[15] brown hyena, spotted hyena, common warthog and vervet monkey. The delta also hosts over 400 bird species, including African fish eagle, Pel's fishing owl, crested crane, lilac-breasted roller, hamerkop and sacred ibis.

The majority of the estimated 200,000 large mammals in and around the delta are not year-round residents. They leave with the summer rains to find renewed fields of grass to graze and trees to browse, then make their way back as winter approaches. Large herds of buffalo and elephant total about 30,000 beasts.

Since 2005, the protected area is considered a Lion Conservation Unit together with Hwange National Park.[16]

Fish

The Okavango Delta is home to 71 fish species, including tigerfish, tilapia, and various species of catfish. Fish sizes range from 1.4 m (4.6 ft) African sharptooth catfish to 3.2 cm (1.3 in) sickle barb. The same species are found in the Zambezi River, indicating a historic link between the two river systems.[17]

Lechwe

The most populous large mammal is the lechwe antelope, with more than 60,000. It is a bit larger than an impala with elongated hooves and a water-repellent substance on their legs that enables rapid movement through knee-deep water. They graze on aquatic plants, and like the waterbuck, take to water when threatened by predators. Only the males have horns.

Plants

Papyrus and reed rafts make up a large part of the Okavango's vegetation. During the flood season, they float well above the sandy river bed with roots dangling free in the water. This gap between bed and roots is used as shelter by crocodiles. The plants of the delta play an important role in providing cohesion for the sand. The banks or levees of a river normally have a high mud content, and this combines with the sand in the river’s load to continuously build up the river banks. In the delta, because the clean waters of the Okavango contain almost no mud, the river’s load consists almost entirely of sand. The plants capture the sand, acting as the glue and making up for the lack of mud and in the process creating further islands on which more plants can take root.

This process is not important in the formation of linear islands. They are long and thin and often curved like a gently meandering river, because they are actually the natural banks of old river channels which over time have become blocked up by plant growth and sand deposition, resulting in the river changing course and the old river levees becoming islands. Due to the flatness of the Delta, and the large tonnage of sand flowing into it from the Okavango River, the floor of the delta is slowly but constantly rising. Where channels are today, islands will be tomorrow and then new channels may wash away these existing islands.[18]

Game lodges

The Botswana Okavango Game Lodges (2011) cater to small numbers of guests, each one operating in its own private concession area. Many lodges have low environmental-effect policies.[19]

People

The Okavango Delta peoples consist of five ethnic groups, each with its own ethnic identity and language. They are Hambukushu (also known as Mbukushu, Bukushu, Bukusu, Mabukuschu, Ghuva, Haghuva), Dceriku (Dxeriku, Diriku, Gciriku, Gceriku, Giriku, Niriku), Wayeyi (Bayei, Bayeyi, Yei), Bugakhwe (Kxoe, Khwe, Kwengo, Barakwena, G/anda) and ||anikhwe (Gxanekwe, //tanekwe, River Bushmen, Swamp Bushmen, G//ani, //ani, Xanekwe). The Hambukushu, Dceriku, and Wayeyi have traditionally engaged in mixed economies of millet/sorghum agriculture, fishing, hunting, the collection of wild plant foods, and pastoralism.

The Bugakhwe and ||anikwhe are Bushmen, who have traditionally practised fishing, hunting, and the collection of wild plant foods; Bugakhwe used both forest and riverine resources, while the ||anikhwe mostly focused on riverine resources. The Hambukushu, Dceriku, and Bugakhwe are present along the Okavango River in Angola and in the Caprivi Strip of Namibia, and small numbers of Hambukushu and Bugakhwe are in Zambia, as well. Within the Okavango Delta, over the past 150 years or so, Hambukushu, Dceriku, and Bugakhwe have inhabited the Panhandle and the Magwegqana in the northeastern Delta. ||anikhwe have inhabited the Panhandle and the area along the Boro River through the Delta, as well as the area along the Boteti River.

The Wayeyi have inhabited the area around Seronga as well as the southern Delta around Maun, and a few Wayeyi live in their putative ancestral home in the Caprivi Strip. Within the past 20 years many people from all over the Okavango have migrated to Maun, the late 1960s and early 1970s over 4,000 Hambukushu refugees from Angola were settled in the area around Etsha in the western Panhandle.

The Okavango Delta has been under the political control of the Batawana (a Tswana nation) since the late 18th century.[20] Led by the house of Mathiba I, the leader of a Bangwato offshoot, the Batawana established complete control over the delta in the 1850s as the regional ivory trade exploded.[21] Most Batawana, however, have traditionally lived on the edges of the delta, due to the threat that tsetse fly poses to their cattle. During a hiatus of some 40 years, the tsetse fly retreated and most Batawana lived in the swamps from 1896 through the late 1930s. Since then, the edge of the delta has become increasingly crowded with its growing human and livestock populations.

Molapo's

After the flooding season, the waters in the lower parts of the delta, near the base, recede, leaving moisture behind in the soil. This residual moisture is used for planting fodder and other crops that can thrive on it. This land is locally known as molapo.

During 1974 to 1978, the floods were more intensive than normal and flood recession cropping was not possible, so severe food and fodder shortages occurred. In response, the Molapo Development Project was initiated. It protected the molapo areas with bunds to control the flooding and prevent severe flooding. The bunds are provided with sluice gates so the stored water can be released and flood recession cropping can start. [22]

Possible threats

The Namibian government has presented plans to build a hydropower station in the Zambezi Region, which would regulate the Okavango's flow to some extent. While proponents argue that the effect would be minimal, environmentalists argue that this project could destroy most of the rich animal and plant life in the Delta.[23] Other threats include local human encroachment and regional extraction of water in both Angola and Namibia.[24][25]

South African filmmaker and conservationist Rick Lomba warned in the 1980s of the threat of cattle invasion to the area. His documentary The End of Eden portrayed his lobbying on behalf of the delta.

See also

References

- ↑ "Okavango Delta System". Ramsar Sites Information Service. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- ↑ Cecil Keen. 1997

- ↑ T.S. McCarthy. 1993. The great inland deltas of Africa, Journal of African Earth Sciences, vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 275-291

- ↑ "Seven Natural Wonders of Africa – Seven Natural Wonders". sevennaturalwonders.org.

- ↑ Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "World Heritage List reaches 1000 sites with inscription of Okavango Delta in Botswana". whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ↑ Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Twenty six new properties added to World Heritage List at Doha meeting". whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ↑ http://blog.africabespoke.com/okavango-delta-part-2/ Archived 19 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Okavango Delta

- ↑ Bradley, John H. (October 2009). "Gliding in a Mokoro Through the Okavango Delta, Botswana". Cape Town to Cairo Website. CapeTowntoCairo.com. Retrieved 2009-11-10.

- ↑ Mbaiwa, J.E. and Mbaiwa, O.I. (2006). The effects of veterinary fences on wildlife populations in Okavango Delta, Botswana. International Journal of Wilderness 12(3): 17−41.

- ↑ McCarthy, T.S., Ellery, W.N. and Bloem, A. (1998). Some observations on the geomorphological impact of hippopotamus (Hippopotamus amphibius L.) in the Okavango Delta, Botswana. African Journal of Ecology 36(1): 44−56.

- ↑ Galpine, N.J. (2006). Boma management of black and white rhinoceros at Mombo, Okavango Delta—Some lessons. Ecologic Journal 7: 55−61.

- ↑ Alonso, L. E. and Nordin, L.-A. (eds). (2003). A rapid biological assessment of the aquatic ecosystems of the Okavango Delta, Botswana: High Water Survey. RAP Bulletin of Biological Assessment 27. Conservation International, Washington, DC.

- ↑ Wallace, K.M. and Leslie, A.J. (2008). Diet of the Nile crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus) in the Okavango Delta, Botswana. Journal of Herpetology 42(2): 361−368.

- ↑ Klein, R. (2007). Status report for the cheetah in Botswana. Cat News Special Issue 1: 13−21.

- ↑ Busse, C. (1980). Leopard and lion predation upon chacma baboons living in the Moremi Wildlife Reserve. Botswana Notes and Records: 15−21.

- ↑ IUCN Cat Specialist Group (2006). Conservation Strategy for the Lion Panthera leo in Eastern and Southern Africa. IUCN, Pretoria, South Africa.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- ↑ "Okavango Delta – Part 2 -". blog.africabespoke.com. Archived from the original on 19 July 2009. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 30 March 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- ↑ Moanaphuti Segolodi, "Ditso Tsa Batawana," 1940. https://www.academia.edu/12170767/Ditso_Tsa_Batawana_by_Moanaphuti_Segolodi_1940

- ↑ Barry Morton, "The Hunting Trade and the Reconstruction of Northern Tswana Societies after the Difaqane, 1838-1880," South African Historical Journal 36 (1997): 220-239. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02582479708671276

- ↑ L.F. Kortenhorst et al., 1986. Development of flood-recession cropping in the molapo's of the Okavango Delta, Botswana. Published in Annual Report 1986, p. 8 – 19 International Institute for Land Reclamation and Improvement Wageningen, The Netherlands (public domain). On line:

- ↑ "FindArticles.com - CBSi". findarticles.com. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ↑ "Threats - Okavango Delta". www.okavangodelta.com. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ↑ "Chinese-Angolan project in Angola harvests over 1,200 tons of rice". 11 March 2016.

- C. Michael Hogan. 2009

Sources

- P. Allison. 2007. Whatever You Do, Don't Run: True Tales Of A Botswana Safari Guide

- J. Bock. 2002. Learning, Life History, and Productivity: Children’s lives in the Okavango Delta of Botswana. Human Nature 13(2). 161-198. Full text

- C. Michael Hogan. 2009. Painted Hunting Dog: Lycaon pictus, GlobalTwitcher.com, ed. N. Stromberg

- Cecil Keen. 1997. Okavango Delta

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Okavango Delta. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Okavango Delta. |

- Conservation International

- Earth-Touch.com Okavango Delta HD Videos

- Flow : information for Okavango Delta planning is the weblog of the Library of the Harry Oppenheimer Okavango Research Institute

- The Ngami Times is Ngamiland's weekly newspaper

- Official Botswana Government site on Moremi Game Reserve, inside the Okavango Delta

- Picture gallery of wildlife in the Okavango Delta

- Wild Entrust International

- Seven Natural Wonders of Africa

- Discovery Channel - Kalahari Flood

- Flood-recession cropping in the molapos of the Okavango Delta

- Okavango Research Institute

- Current Okavango water levels, weather data and satellite images

- 1986 Documentary The End of Eden by Rick Lomba

- Top 25 Photographs

- Southern African Game Reserves - Okavango Delta