Ross Sea

| Ross Sea | |

|---|---|

Sea ice in the Ross Sea | |

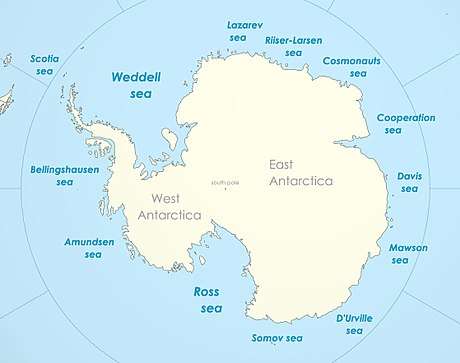

Seas of Antarctica, with the Ross Sea in the bottom-left | |

| Location | Antarctica |

| Type | Sea |

| Etymology | James Ross |

| Primary outflows | Southern Ocean |

The Ross Sea is a deep bay of the Southern Ocean in Antarctica, between Victoria Land and Marie Byrd Land and within the Ross Embayment, and is the southernmost sea on Earth. It derives its name from the British explorer James Ross who visited this area in 1841. To the west of the sea lies Ross Island and Victoria Land, to the east Roosevelt Island and Edward VII Peninsula in Marie Byrd Land, while the southernmost part is covered by the Ross Ice Shelf, and is about 200 miles (320 km) from the South Pole. Its boundaries and area have been defined by the New Zealand National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research as having an area of 637,000 square kilometres (246,000 sq mi).[1]

The circulation of the Ross Sea is dominated by a wind-driven ocean gyre and the flow is strongly influenced by three submarine ridges that run from southwest to northeast. The circumpolar deep water current is a relatively warm, salty and nutrient-rich water mass that flows onto the continental shelf at certain locations. The Ross Sea is covered with ice for most of the year.

The nutrient-laden water supports an abundance of plankton and this encourages a rich marine fauna. At least ten mammal species, six bird species and 95 fish species are found here, as well as many invertebrates, and the sea remains relatively unaffected by human activities. New Zealand has claimed that the sea comes under their jurisdiction as part of the Ross Dependency. Marine biologists consider the sea to have a high level of biological diversity and it is the site of much scientific research. It is also the focus of some environmentalist groups who have campaigned to have the area proclaimed as a world marine reserve. In 2016 an international agreement established the region as a marine park.[2]

Description

The Ross Sea was discovered by James Ross in 1841. In the west of the Ross Sea is Ross Island with the Mt. Erebus volcano, in the east Roosevelt Island. The southern part is covered by the Ross Ice Shelf.[3] Roald Amundsen started his South Pole expedition in 1911 from the Bay of Whales, which was located at the shelf. In the west of the Ross sea, McMurdo Sound is a port which is usually free of ice during the summer. The southernmost part of the Ross Sea is Gould Coast, which is approximately two hundred miles from the geographic South Pole.

Geology

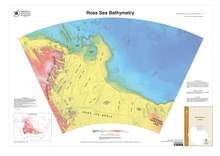

The continental shelf

The Ross Sea (and Ross Ice Shelf) overlies a deep continental shelf. Although the average depth of the world’s continental shelves (at the shelf break joining the continental slope) is about 130 meters,[4][5] the Ross shelf average depth is about 500 meters.[6] It is shallower in the western Ross Sea (east longitudes) than the east (west longitudes).[6] This over-deepened condition is due to cycles of erosion and deposition of sediments from expanding and contracting ice sheets overriding the shelf since Oligocene time,[7] and is also found on other locations around Antarctica.[8] Erosion was more focused on the inner parts of the shelf while deposition of sediment dominated the outer shelf, making the inner shelf deeper than the outer.[7][9]

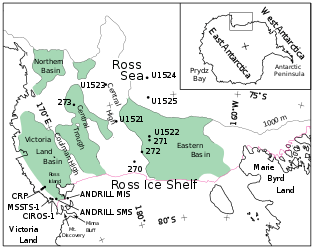

Seismic studies in the latter half of the twentieth century defined the major features of the geology of the Ross Sea.[10] The deepest or basement rocks, are faulted into three major north trending grabens, which are basins for sedimentary fill. These basins include the Victoria Land Basin in the west, the Central Trough, and the Eastern Basin, which has approximately the same width as the other two. The Coulman High separates the Victoria Land Basin and Central Trough and the Central High separates the Central Trough and Eastern Basin. The majority of the faulting and accompanying graben formation along with crustal extension occurred during the rifting away of the Zealandia microcontinent from Antarctica in Gondwana during Cretaceous time.[11] Neogene-age faulting and extension is restricted to the Terror Rift within the Victoria Land Basin.[12]

Stratigraphy

Basement grabens are filled with rift sediments of unknown character and age.[10] A widespread unconformity has cut into the basement and sedimentary fill of the large basins.[10][13] Above this major unconformity are a series of glacial marine sedimentary units deposited during multiple advances and retreats of the Antarctic Ice Sheet across the sea floor of the Ross Sea during the Oligocene and later.[7]

Geologic Drilling

Drill holes have recovered cores of rock from the western edges of the sea.[14][15][16] Deep Sea Drilling Project (DSDP) Leg 28 completed several holes (270-273) farther from land in the central and western portions of the sea.[17] These resulted in defining a stratigraphy for most of the glacial sequences, which comprise Oligocene and younger sediments. The Ross Sea-wide major unconformity has been proposed to mark a global climate event and the first appearance of the Antarctic Ice Sheet in the Oligocene.[18][19][20]

During 2018 Expedition 374 of the International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP), the latest successor to the DSDP, drilled additional holes (U1521-1525) in the central Ross Sea for Neogene and Quaternary ice sheet history.[21]

Basement

The nature of the basement rocks and the fill within the grabens are unknown except in few locations. Basement rocks have not been sampled except at DSDP Leg 28 drill site 270 where metamorphic rocks of unknown age were recovered,[17] and in the eastern Ross Sea where a bottom dredge was collected.[22] In both these locations the metamorphic rocks are Cretaceous-age mylonites suggesting extreme stretching of the Ross Embayment during that time.[23][22] It is likely that rocks of the Ross System exposed onshore in Victoria Land form much of the basement rock in the western Ross Sea,[24][25] including the Beacon Sandstone of Devonian-Jurassic age.[26].

Marie Byrd Land - Rocks exposed in western Marie Byrd Land on the Edward VII Peninsula and within the Ford Ranges are candidates for basement in the eastern Ross Sea.[27] The oldest rocks are Permian sediments of the Swanson Formation, which is slightly metamorphosed. The Ford granodiorite of Devonian age intrudes these sediments. Cretaceous Byrd Coast granite in turn intrudes the older rocks. The Byrd Coast and older formations have been cut by basalt dikes. Scattered through the Ford Ranges and Fosdick Mountains are late Cenozoic volcanic rocks that are not found to the west on Edward VII Peninsula. Metamorphic rocks, migmatites, are found in the Fosdick Mountains and Alexandra Mountains.[28][29] These were metamorphosed and deformed in the Cretaceous.[30][31]

The Ross System - Ross System rocks exposed in the Transantarctic Mountains on the western side of the Ross Sea[24][25] are possible basement rock below the sedimentary cover of the sea floor. The rocks are of upper Precambrian to lower Paleozoic age and each group of Ross System have an echelon vein pattern demonstrating possible dextral faulting. These miogeosyncline metasedimentary rocks are usually folded about northwest and southeast axes and are partly composed of calcium carbonate, often including limestone. Groups within the Ross System include the Robertson Bay Group, Priestley Group, Skelton Group, Beardmore Group, Byrd Group, Queen Maud Group, and Koettlitz Group. The Robertson Bay Group ranges from 56 to 76% silica and compares closely with other Ross System members. The Priestley Group rocks are similar to those of the Robertson Bay Group and include dark slates, argillites, siltstones, fine sandstones and limestones. They can be found near the Priestley and Campbell glaciers. For thirty miles along the lower Skelton Glacier are the calcareous greywackes and argillites of the Skelton Group. The region between the lower Beardmore Glacier and the lower Shackelton Glacier sits the Beardmore Group. North of the Nimrod Glacier are four block faulted ranges that make up the Byrd Group. The contents of the Queen Maud Group area are mainly post-tectonic granite.

Oceanography

Circulation

The Ross Sea circulation, dominated by polynya processes, is in general very slow-moving. Circumpolar Deep Water (CDW) is a relatively warm, salty and nutrient-rich water mass that flows onto the continental shelf at certain locations in the Ross Sea. Through heat flux, this water mass moderates the ice cover. The near-surface water also provides a warm environment for some animals and nutrients to excite primary production. CDW transport onto the shelf is known to be persistent and periodic, and is thought to occur at specific locations influenced by bottom topography. The circulation of the Ross Sea is dominated by a wind-driven gyre. The flow is strongly influenced by three submarine ridges that run from southwest to northeast. Flow over the shelf below the surface layer consists of two anticyclonic gyres connected by a central cyclonic flow. The flow is considerable in spring and winter, due to influencing tides. The Ross Sea is covered with ice for much of the year and ice concentrations and in the south-central region little melting occurs. Ice concentrations in the Ross Sea are influenced by winds with ice remaining in the western region throughout the austral spring and generally melting in January due to local heating. This leads to extremely strong stratification and shallow mixed layers in the western Ross Sea.[32]

Ecological importance and conservation

The Ross Sea is one of the last stretches of seas on Earth that remains relatively unaffected by human activities.[33] Because of this, it remains almost totally free from pollution and the introduction of invasive species. Consequently, the Ross Sea has become a focus of numerous environmentalist groups who have campaigned to make the area a world marine reserve, citing the rare opportunity to protect the Ross Sea from a growing number of threats and destruction. The Ross Sea is regarded by marine biologists as having a very high biological diversity and as such has a long history of human exploration and scientific research, with some datasets going back over 150 years.[34][35]

Biodiversity

The Ross Sea is home to at least 10 mammal species, half a dozen species of birds, 95 species of fish, and over 1,000 invertebrate species. Some species of birds that nest in and near the Ross Sea include the Adélie penguin, emperor penguin, Antarctic petrel, snow petrel, and south polar skua. Marine mammals in the Ross Sea include the Antarctic minke whale, killer whale, Weddell seal, crabeater seal, and leopard seal. Antarctic toothfish, Antarctic silverfish, Antarctic krill, and crystal krill also swim in the cold Antarctic water of the Ross Sea.[36]

The flora and fauna are considered similar to other southern Antarctic marine regions. Particularly in Summer, the nutrient-rich sea water supports an abundant planktonic life in turn providing food for larger species, such as fish, seals, whales, and sea- and shore-birds.

Albatrosses rely on wind to travel and cannot get airborne in a calm. The westerlies do not extend as far south as the ice edge and therefore albatrosses do not travel often to the ice-pack. An albatross would be trapped on an ice floe for many days if it landed in the calm.[37]

The coastal parts of the sea contain a number of rookeries of Adélie and Emperor penguins, which have been observed at a number of places around the Ross Sea, both towards the coast and outwards in open sea.[3]

A 10-metre (32.8 feet) long colossal squid weighing 495 kilograms (1,091 lb) was captured in the Ross Sea on February 22, 2007.[38][39][40][41][42]

Toothfish Fishery

In 2010, the Ross Sea Antarctic toothfish fishery was independently certified by the Marine Stewardship Council,[43] and has been rated as a 'Good Alternative' by the Monterey Bay Aquarium Seafood Watch program. However, a 2008 document submitted to the CCAMLR reported significant declines in toothfish populations of McMurdo Sound coinciding with the development of the industrial toothfishing industry since 1996, and other reports have noted a coincident decrease in the number of orcas. The report recommended a full moratorium on fishing over the Ross shelf.[44] In October 2012, Philippa Ross, James Ross' great, great, great granddaughter, voiced her opposition to fishing in the area.[45]

In the southern winter of 2017 New Zealand scientists discovered the breeding ground of the Antarctic toothfish in the northern Ross Sea seamounts for the first time[46] underscoring how little is known about the species.

Marine Protected Area

Beginning in 2005, the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) commissioned scientific analysis and planning for Marine Protected Areas (MPA) in the Antarctic. In 2010, the CCAMLR endorsed their Scientific Committee’s proposal to develop Antarctic MPAs for conservation purposes. The US State Department submitted a proposal for a Ross Sea MPA at the September 2012 meeting of the CCAMLR.[47] At this stage, a sustained campaign by various international and national NGOs commenced to accelerate the process[48].

In July 2013, the CCAMLR held a meeting in Bremerhaven in Germany, to decide whether to turn the Ross Sea into an MPA. The deal failed due to Russia voting against it, citing uncertainty about whether the commission had the authority to establish a marine protected area.[49]

In October 2014, the MPA proposal was again defeated at the CCAMLR by votes against from China and Russia.[50] At the October 2015 meeting a revised MPA proposal from the US and New Zealand was expanded with the assistance of China, who however shifted the MPA's priorities from conservation by allowing commercial fishing. The proposal was again blocked by Russia.[51]

On 28 October 2016, at its annual meeting in Hobart, a Ross Sea marine park was finally declared by the CCAMLR, under an agreement signed by 24 countries and the European Union. It protected over 1.5 million square kilometres of sea, and was the world's largest protected area at the time. However, a sunset provision of 35 years was inserted as part of negotiations, which means it does not meet the International Union for Conservation of Nature definition of a marine protected area, which requires it to be permanent.[2]

See also

References

- ↑ "About the Ross Sea". NIWA. 27 July 2012. Archived from the original on 24 February 2018. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

- 1 2 Slezak, Michael (26 October 2016). "World's largest marine park created in Ross Sea in Antarctica in landmark deal". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 28 October 2016. Retrieved 28 October 2016.

- 1 2 "Ross Sea (sea, Pacific Ocean) - Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Archived from the original on 11 March 2012. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- ↑ Gross, M. Grant (1977). Oceanography: A view of the Earth (6 ed.). New Jersey: Prentice Hall. p. 28.

- ↑ Shepard, F.P. (1963). Submarine Geology (2 ed.). New York: Harper & Row. p. 264.

- 1 2 Hayes, D.E.; Davey, F.J. A Geophysical Study of the Ross Sea, Antarctica (PDF). doi:10.2973/dsdp.proc.28.134.1975. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 July 2017.

- 1 2 3 Bartek, L. R.; Vail, P. R.; Anderson, J. B.; Emmet, P. A.; Wu, S. (1991-04-10). "Effect of Cenozoic ice sheet fluctuations in Antarctica on the stratigraphic signature of the Neogene". Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth. 96 (B4): 6753–6778. doi:10.1029/90jb02528. ISSN 2156-2202.

- ↑ Barker, P.F., Barrett, P.J., Camerlenghi, A., Cooper, A.K., Davey, F.J., Domack, E.W., Escutia, C., Kristoffersen, Y. and O'Brien, P.E. (1998). "Ice sheet history from Antarctic continental margin sediments: the ANTOSTRAT approach". Terra Antarctica. 5 (4): 737–760.

- ↑ Ten Brink, Uri S.; Schneider, Christopher; Johnson, Aaron H. (1995). "Morphology and stratal geometry of the Antarctic continental shelf: insights from models". In Cooper, Alan K.; Barker, Peter F.; Brancolini, Giuliano. Geology and Seismic Stratigraphy of the Antarctic Margin. American Geophysical Union. pp. 1–24. doi:10.1029/ar068p0001. ISBN 9781118669013.

- 1 2 3 The Antarctic continental margin : geology and geophysics of the western Ross Sea. Cooper, Alan K., Davey, Frederick J., Circum-Pacific Council for Energy and Mineral Resources. Houston, Tex., U.S.A.: Circum-Pacific Council for Energy and Mineral Resources. 1987. ISBN 0933687052. OCLC 15366732.

- ↑ Lawver, L. A., and L. M. Gahagan. 1994. "Constraints on timing of extension in the Ross Sea region." Terra Antartica1:545-552.

- ↑ Davey, F. J.; Cande, S. C.; Stock, J. M. (2006-10-27). "Extension in the western Ross Sea region-links between Adare Basin and Victoria Land Basin". Geophysical Research Letters. 33 (20). doi:10.1029/2006gl027383. ISSN 0094-8276.

- ↑ Geology and seismic stratigraphy of the Antarctic margin, 2. Barker, Peter F., Cooper, Alan K. Washington, D.C.: American Geophysical Union. 1997. ISBN 9781118668139. OCLC 772504633.

- ↑ Barrett, P. J.; Treves, S. B. (1981), "Sedimentology and petrology of core from DVDP 15, western McMurdo Sound", Dry Valley Drilling Project, American Geophysical Union, pp. 281–314, doi:10.1029/ar033p0281, ISBN 0875901778, retrieved 2018-08-28

- ↑ Davey, F. J.; Barrett, P. J.; Cita, M. B.; van der Meer, J. J. M.; Tessensohn, F.; Thomson, M. R. A.; Webb, P.-N.; Woolfe, K. J. (2001). "Drilling for Antarctic Cenozoic climate and tectonic history at Cape Roberts, Southwestern Ross Sea". Eos, Transactions American Geophysical Union. 82 (48): 585–585. doi:10.1029/01eo00339. ISSN 0096-3941.

- ↑ Paulsen, Timothy S.; Pompilio, Massimo; Niessen, Frank; Panter, Kurt; Jarrard, Richard D. (2012). "Introduction: The ANDRILL McMurdo Ice Shelf (MIS) and Southern McMurdo Sound (SMS) Drilling Projects". Geosphere. 8 (3): 546–547. doi:10.1130/ges00813.1. ISSN 1553-040X.

- 1 2 Hayes, D.E.; Frakes, L.A. (1975), "General Synthesis, Deep Sea Drilling Project Leg 28" (PDF), Initial Reports of the Deep Sea Drilling Project, U.S. Government Printing Office, doi:10.2973/dsdp.proc.28.136.1975, retrieved 2018-08-28

- ↑ Anderson, John B.; Bartek, Louis R. (1992), "Cenozoic glacial history of the Ross Sea revealed by intermediate resolution seismic reflection data combined with drill site information", The Antarctic Paleoenvironment: A Perspective on Global Change: Part One, American Geophysical Union, pp. 231–263, doi:10.1029/ar056p0231, ISBN 0875908233, retrieved 2018-08-28

- ↑ Brancolini, Giuliano; Cooper, Alan K.; Coren, Franco (2013-03-16), "Seismic Facies and Glacial History in the Western Ross Sea (Antarctica)", Geology and Seismic Stratigraphy of the Antarctic Margin, American Geophysical Union, pp. 209–233, doi:10.1029/ar068p0209, ISBN 9781118669013, retrieved 2018-08-28

- ↑ Decesari, Robert C., Christopher C. Sorlien, Bruce P. Luyendyk, Douglas S. Wilson, Louis Bartek, John Diebold, and Sarah E. Hopkins (2007-07-24). "USGS Open-File Report 2007-1047, Short Research Paper 052". Regional Seismic Stratigraphic Correlations of the Ross Sea: Implications for the Tectonic History of the West Antarctic Rift System. 2007 (1047sir052). doi:10.3133/of2007-1047.srp052. ISSN 0196-1497.

- ↑ Robert M. McKay; Laura De Santis; Denise K. Kulhanek; and the Expedition Scientists 374 (2018-05-24). International Ocean Discovery Program Expedition 374 Preliminary Report. International Ocean Discovery Program Preliminary Report. International Ocean Discovery Program. doi:10.14379/iodp.pr.374.2018.

- 1 2 Siddoway, Christine Smith; Baldwin, Suzanne L.; Fitzgerald, Paul G.; Fanning, C. Mark; Luyendyk, Bruce P. (2004). "Ross Sea mylonites and the timing of intracontinental extension within the West Antarctic rift system". Geology. 32 (1): 57. doi:10.1130/g20005.1. ISSN 0091-7613.

- ↑ Fitzgerald, P. G., and S. L. Baldwin. 1997. "Detachment Fault Model for the Evolution of the Ross Embayment." In The Antarctic Region: Geological Evolution and Processes, edited by C. A. Ricci, 555-564. Siena: Terra Antarctica Pub.

- 1 2 Faure, Gunter; Mensing, Teresa M. (2011). "The Transantarctic Mountains". doi:10.1007/978-90-481-9390-5.

- 1 2 Stump, Edmund (1995). The Ross orogen of the Transantarctic Mountains. Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521433142. OCLC 30671271.

- ↑ Barrett, P. J. (1981). "History of the Ross Sea region during the deposition of the Beacon Supergroup 400 - 180 million years ago". Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 11 (4): 447–458. doi:10.1080/03036758.1981.10423334. ISSN 0303-6758.

- ↑ Luyendyk, Bruce P.; Wilson, Douglas S.; Siddoway, Christine S. (2003). "Eastern margin of the Ross Sea Rift in western Marie Byrd Land, Antarctica: Crustal structure and tectonic development". Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems. 4 (10). doi:10.1029/2002gc000462. ISSN 1525-2027.

- ↑ Luyendyk, B. P. , S. M. Richard, C. H. Smith, and D. L. Kimbrough. 1992. "Geological and geophysical investigations in the northern Ford Ranges, Marie Byrd Land, West Antarctica." In Recent Progress in Antarctic Earth Science: Proceedings of the 6th Symposium on Antarctic Earth Science, Saitama, Japan, 1991, edited by Y. Yoshida, K. Kaminuma and K. Shiraishi, 279-288. Tokyo, Japan: Terra Pub.

- ↑ Richard, S. M.; Smith, C. H.; Kimbrough, D. L.; Fitzgerald, P. G.; Luyendyk, B. P.; McWilliams, M. O. (1994). "Cooling history of the northern Ford Ranges, Marie Byrd Land, West Antarctica". Tectonics. 13 (4): 837–857. doi:10.1029/93tc03322. ISSN 0278-7407.

- ↑ Siddoway, C., S. Richard, C. M. Fanning, and B. P. Luyendyk. 2004. "Origin and emplacement mechanisms for a middle Cretaceous gneiss dome, Fosdick Mountains, West Antarctica (Chapter 16)." In Gneiss domes in orogeny, edited by D. L. Whitney, C. T. Teyssier and C. Siddoway, 267-294. Geological Society of America Special Paper 380.

- ↑ Korhonen, F. J.; Brown, M.; Grove, M.; Siddoway, C. S.; Baxter, E. F.; Inglis, J. D. (2011-10-17). "Separating metamorphic events in the Fosdick migmatite-granite complex, West Antarctica". Journal of Metamorphic Geology. 30 (2): 165–192. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1314.2011.00961.x. ISSN 0263-4929.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 23 December 2013.

- ↑ Ballard, Grant; Jongsomjit, Dennis; Veloz, Samuel D.; Ainley, David G. (1 November 2012). "Coexistence of mesopredators in an intact polar ocean ecosystem: The basis for defining a Ross Sea marine protected area". Biological Conservation. 156: 72–82. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2011.11.017.

- ↑ (dead link) Archived 25 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Antarctic and Southern Ocean Coalition. "The Ross Sea" (PDF). The Ross Sea - Antarctic and Southern Ocean Coalition. ASOC. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 May 2012. Retrieved 26 April 2016.

- ↑ "Ross Sea Species". www.lastocean.org. Archived from the original on 17 December 2013.

- ↑ "Sub-Antarctic and Polar bird life". archive.org. 23 April 2015. Archived from the original on 23 April 2015.

- ↑ "World's largest squid landed in NZ - Beehive (Govt of NZ)". 2007-02-22. Archived from the original on 23 May 2010. Retrieved 2013-06-11.

- ↑ "NZ fishermen land colossal squid - BBC News". 22 February 2007. Archived from the original on 17 September 2013. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- ↑ "Colossal squid's headache for science - BBC News". 15 March 2007. Archived from the original on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- ↑ "Size matters on 'squid row' (+photos, video) - The New Zealand Herald". 2008-05-01. Retrieved 2013-06-11.

- ↑ "Colossal squid's big eye revealed - BBC News". 30 April 2008. Archived from the original on 19 September 2013. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- ↑ Marine Stewardship Council. "Ross Sea toothfish longline — Marine Stewardship Council". www.msc.org. Archived from the original on 13 May 2016. Retrieved 26 April 2016.

- ↑ DeVries, Arthur L.; Ainley, David G.; Ballard, Grant. "Decline of the Antarctic toothfish and its predators in McMurdo Sound and the southern Ross Sea, and recommendations for restoration" (PDF). CCAMLR. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 January 2016. Retrieved 26 April 2016.

- ↑ "Ross descendant wants sea protected". 3 News NZ. 29 October 2012.

- ↑ "Peeping in on the Mile Deep Club | Hakai Magazine". Hakai Magazine. Archived from the original on 17 August 2017. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- ↑ Delegation of the United States. "A PROPOSAL FOR THE ROSS SEA REGION MARINE PROTECTED AREA" (PDF). Proposed Marine Protected Area in Antarctica's Ross Sea. U.S. Department of State. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 June 2016. Retrieved 26 April 2016.

- ↑ "Antarctic Oceans Alliance". www.antarcticocean.org. Archived from the original on 17 August 2017. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- ↑ New Scientist, No. 2926, 20 July, "Fight to preserve last pristine ecosystem fails"

- ↑ Mathiesen, Karl (31 October 2014). "Russia accused of blocking creation of vast Antarctic marine reserves". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 13 May 2016. Retrieved 26 April 2016.

- ↑ The Pew Charitable Trusts. "Pew: Nations Miss Historic Opportunity to Protect Antarctic Waters". www.prnewswire.com. Archived from the original on 9 May 2016. Retrieved 26 April 2016.

External links

![]()

- Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources, New Zealand and United States Delegation, 2015. A proposal for the establishment of a Ross Sea Region Marine Protected Area

- J.Glausiusz, 2007, Raw Data: Beacon Bird of Climate Change. Discover Magazine.

- Gunn, B., nd, Geology The Ross Sea Dependency including Victoria-Land Ross Sea, Antarctica, Including the Ross Sea Dependency, the Sub-Antarctic Islands and sea, up to New Zealand from the Pole.

- K.Hansen, 2007, Paleoclimate: Penguin poop adds to climate picture. Geotimes.

- International Polar Foundation, 2007, Interview with Dr. Steven Emslie: The Adélie Penguins' Diet Shift. SciencePoles website.

- C.Michael Hogan. 2011. Ross Sea. Eds. P.Saundry & C.J.Cleveland. Encyclopedia of Earth. National Council for Science and the Environment. Washington DC

- Locarnini, R.A., 1995, the Ross Sea. Quarterdeck, vol. 1, no. 3.(Department of Oceanography, Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas.)

- "Nth Korean boats caught fishing in conservation area". Radio New Zealand. Retrieved 7 April 2011.

- http://www.antarcticocean.org/. International campaign to establish Marine Protected Areas in the Southern Ocean.

- The Last Ocean, documentary film on the Ross Sea and the international debate over its fate.

.svg.png)