Ossetians

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 750,000[a] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 558,515[1] | |

| (in | 480,310[2] |

| 51,000[3][4] | |

(excluding South Ossetia) |

14,385[5] Diaspora |

| 50,000[6][7][8] | |

| 7,861[9] | |

| 5,823[10] | |

| 4,830[11] | |

| 4,308[12] | |

| 2,066[13] | |

| 1,170[14] | |

| 758[15] | |

| 700[16] | |

| 554[17] | |

| 403[18] | |

| 331[19] | |

| 285[20] | |

| 119[21] | |

| 116[22] | |

| Languages | |

| Ossetian, Russian, Georgian | |

| Religion | |

|

Predominantly † Eastern Orthodox Christianity with a sizeable minority professing Uatsdin, and Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

|

Scythians, Sarmatians, Alans Other Iranian peoples, the Jassic people of Hungary, neighbouring peoples of the Caucasus. | |

|

a. ^ The total figure is merely an estimation; sum of all the referenced populations. | |

The Ossetians or Ossetes (/ɒˈsɛtiənz/; Ossetian: ир, ирæттæ, ir, irættæ; дигорæ, дигорæнттæ, digoræ, digorænttæ) are an Iranian ethnic group of the Caucasus Mountains, indigenous to the ethnolinguistic region known as Ossetia.[23][24][25] They speak Ossetic, an Eastern Iranian (Alanic) language of the Indo-European languages family, with most also fluent in Russian as a second language. The Ossetian language is neither closely related to nor mutually intelligible with any other language of the family today.[26] Ossetic, a remnant of the Scytho-Sarmatian dialect group which was once spoken across the Steppe, is one of few Iranian languages inside Europe.[27]

The Ossetians are mostly Eastern Orthodox Christian, with a sizeable minority professing Uatsdin and Islam.

The Ossetians mostly populate Ossetia, which is politically divided between North Ossetia–Alania in Russia, and South Ossetia, a de facto independent state with partial recognition, closely integrated in Russia and claimed by Georgia.

Their closest relatives, the Jász, live in the Jászság region within the north-western part of the Jász-Nagykun-Szolnok County in Hungary.

Etymology

The Ossetians and Ossetia received their name from the Russians, who adopted the Georgian designations Osi (ოსი) (sing., pl.: Osebi (ოსები)) and Oseti ("the land of Osi" (ოსეთი)), used since the Middle Ages for the single Iranian-speaking population of the Central Caucasus and probably based on the old Alan self-designation "As". As the Ossetians lacked any single inclusive name for themselves in their native language, these terms were accepted by the Ossetians themselves already before their integration into the Russian Empire.[28]

This practice was put into question by the new Ossetian nationalism in the early 1990s, when the dispute between the Ossetian subgroups of Digoron and Iron over the status of the Digoron dialect made the Ossetian intellectuals search for a new inclusive ethnic name. This, combined with the effects of the Georgian-Ossetian conflict, led to the popularization of "Alania", the name of the medieval Sarmatian confederation, to which the Ossetians traced their origin, and inclusion of this name into the official republican title of North Ossetia in 1994.[28]

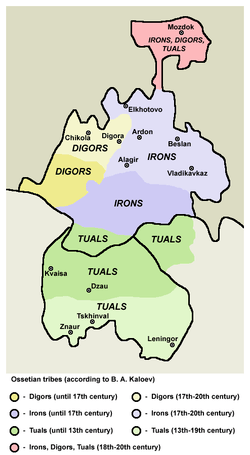

Subgroups

- Iron in the east and south form a larger group of Ossetians. Irons are divided into several subgroups: Alagirs, Kurtats, Tagaurs, Kudar, Tual, Urstual, Chsan.

- Digoron in the west. Digors live in Digora district, Iraf district and in some settlements in Kabardino-Balkaria and Mozdok district. Digors in Digora district are Christian, while those living in Iraf district are Muslim. They speak Digor dialect.

Culture

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of South Ossetia |

|---|

|

| History |

| People |

| Languages |

|

Mythology and folklore |

| Cuisine |

| Religion |

| Literature |

|

Music and performing arts |

|

Symbols |

|

|

Mythology

The folk beliefs of the Ossetian people are rooted in their Sarmatian origin and Christian religion, with the pagan gods transcending into Christian saints. The Nart saga serves the basic pagan mythology of the region.[31]

Music

History

Prehistory (Early Alans)

The Ossetians descend from the Alans,[32] a Sarmatian tribe (Scythian subgroup of the Iranian ethnolinguistic group).[33] About AD 200, the Alans were the only branch of the Sarmatians to keep their culture in the face of a Gothic invasion, and the Alans remaining built up a great kingdom between the Don and the Volga, according to Coon, The Races of Europe. Between AD. 350 and 374, the Huns destroyed the Alan kingdom, and the Alan people was splitted into two parts. One of them fled further to the West and participated in the Barbarian Inasions towards Rome, establishing short-lived kingdoms in Spain and North Africa and settling in the lot of places, including Orleans, France. The other part fled further South and settled on the plains of North Caucasus, where Alans established their medieval kingdom of Alania.

Middle Ages

In the 8th century a consolidated Alan kingdom, referred to in sources of the period as Alania, emerged in the northern Caucasus Mountains, roughly in the location of the latter-day Circassia and the modern North Ossetia–Alania. At its height, Alania was a centralized monarchy with a strong military force and had a strong economy which benefited from the Silk Road.

However, after the Mongol invasions of the 1200s the Alans were forced out of their medieval homeland south of the River Don in present-day Russia. Due to this, the Alans migrated towards the Caucasus mountains, where they would form three ethnographical groups; the Iron, Digoron, and Kudar. The Jassic people were a fourth group that migrated in the 13th century to Hungary.

Modern history

In recent history, the Ossetians participated in Ossetian–Ingush conflict (1991–1992) and Georgian–Ossetian conflicts (1918–1920, early 1990s) and in the 2008 South Ossetia war between Georgia and Russia.

Key events:

- 1774 — North Ossetia becomes part of the Russian Empire.[34]

- 1801 — Following the Treaty of Georgievsk, the modern-day South Ossetia territory becomes part of the Russian Empire, along with Georgia.[35]

- 1922 — Ossetia is divided[36][37] into two parts: North Ossetia remains a part of Russian SFSR, South Ossetia remains a part of Georgian SSR.

- 20 September 1990 – independent Republic of South Ossetia. The republic remained unrecognized, yet it detached itself from Georgia de facto. In the last years of the Soviet Union, ethnic tensions between Ossetians and Georgians in Georgia's former Autonomous Oblast of South Ossetia (abolished in 1990) and between Ossetians and the Ingush in North Ossetia evolved into violent clashes that left several hundreds dead and wounded and created a large tide of refugees on both sides of the border.[38][39]

Language

The Ossetian language belongs to the Eastern Iranian (Alanic) branch of the Indo-European language family.[32]

Ossetian is divided into two main dialect groups: Ironian[32] (os. – Ирон) in North and South Ossetia and Digorian[32] (os. – Дыгурон) of western North Ossetia. There are some subdialects in those two: like Tualian, Alagirian, Ksanian, etc. The Ironian dialect is the most widely spoken.

Ossetian is among the remnants of the Scytho-Sarmatian dialect group which was once spoken across the Steppe. The Ossetian language is not mutually intelligible with any other Iranian language.[26]

Religion

Today, the majority of Ossetians, both from North and South Ossetia, follow Eastern Orthodoxy.[32] In addition to Christianity, Ossetian ethnic religion is also widespread among Ossetians, with ritual traditions like sacrificing animals, holy shrines, non-Christian saints, etc. There are temples, known as kuvandon in most of the villages.[42] According to the research service Sreda, North Ossetia is the primary location where Ossetian Paganism is practiced, and 29% of the population reported practicing pagan faiths in the 2012 Russian Census.[43] Ætsæg Din is the Ossetian ethnic religion, rising in popularity since the 1980s.[44]

History

Prior to the 10th century, Ossetians were a strictly Pagan group. However, they were partially Christianized by Byzantine missionaries in the beginning of the 10th century,[45] By the 13th century, most of the Ossetians were Eastern Orthodox Christians[32] as a result of Georgian influence and missionary work.[46][47] Islam was introduced during the 18th century by the recently converted members of the Circassian Kabarday Tribe (to whom the religion was introduced by Tatars at the time) after taking over territory in western Ossetia occupied by the Digor, although it did not spread to rest of the Ossetian people successfully.[48]

Ossetia became part of the Russian Empire in 1774, which strengthened Orthodox Christianity considerably by sending missionaries there from the Russian Orthodox church. However, most of the missionaries chosen were churchmen from Eastern Orthodox communities living in Georgia (including Armenians and Greeks as well as ethnic Georgians) rather than from Russia, so as to avoid being seen by the Ossetians as too intrusive.

Livelihood

The northern Ossetians export lumber and cultivate various crops, mainly corn. The southern Ossetians are chiefly pastoral, herding sheep, goats, and cattle. Traditional manufactured products include leather goods, fur caps, daggers, and metalware.[32]

Demographics

Outside of South Ossetia, there is also a significant number of Ossetians living in north-central Georgia in Trialeti. A large Ossetian diaspora lives in Turkey, and Ossetians have also settled in Belgium, France, Sweden, Syria, the United States (New York City, Florida and California as examples), Canada (Toronto), Australia (Sydney), and other countries all around the world.

Russian Census of 2002

The vast majority of Ossetians live in Russia (according to the Russian Census (2002)):

.png)

Genetics

The Ossetians are a unique ethnic group of the Caucasus, speaking an Indo-European language surrounded by Caucasian ethnolinguistic groups. The Y-haplogroup data indicate that North Ossetians are more similar to other North Caucasian groups, and South Ossetians are more similar to other South Caucasian groups, than to each other. Also, with respect to mtDNA, Ossetians are significantly more similar to some Iranian groups than to Caucasian groups. It is thus suggested that there is a common origin of Ossetians from the Proto-Iranian Urheimat, followed by subsequent male-mediated migrations from their Caucasian neighbours.[49]

Gallery

Ossetian woman in traditional clothes, early years of the 20th century

Ossetian woman in traditional clothes, early years of the 20th century Ossetian women working (19th century)

Ossetian women working (19th century) Ossetian Northern Caucasia dress of the 18th century, Ramonov Vano (19th century)

Ossetian Northern Caucasia dress of the 18th century, Ramonov Vano (19th century) Three Ossetian teachers (19th century)

Three Ossetian teachers (19th century) Ossetian girl in 1883

Ossetian girl in 1883 Sergei Guriev, economist

Sergei Guriev, economist Nikolay Bagrayev, politician

Nikolay Bagrayev, politician- South Ossetian performers

._F._17._Oss%C3%A8the_(Oss%C3%A8te)%2C_Koban._Mission_scientifique_de_Mr_Ernest_Chantre._1881.jpg) Ossetian man in 1881

Ossetian man in 1881 Veronika Dudarova, symphony conductor

Veronika Dudarova, symphony conductor Soslan Ramonov, professional wrestler

Soslan Ramonov, professional wrestler Shota Bibilov, professional footballer

Shota Bibilov, professional footballer- Ruslan Karaev, professional kickboxer

- Vladimir Gabulov, Ossetian goalkeeper

See also

References

- ↑ "Russian Census 2010: Population by ethnicity" (XLS). Perepis-2010.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 2017-08-21.

- ↑ "Всероссийская перепись населения 2002 года". Perepis2002.ru. Retrieved 2017-08-21.

- ↑ South Ossetia's status is disputed. It considers itself to be an independent state, but this is recognised by only a few other countries. The Georgian government and most of the world's other states consider South Ossetia de jure a part of Georgia's territory.

- ↑ "PCGN Report "Georgia: a toponymic note concerning South Ossetia"" (PDF). Pcgn.org.uk. 2007. p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-06-14. Retrieved 2017-08-21.

- ↑ "Ethnic Composition of Georgia" (PDF). Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- ↑ "Lib.ru/Современная литература: Емельянова Надежда Михайловна. Мусульмане Осетии: На перекрестке цивилизаций. Часть 2. Ислам в Осетии. Историческая ретроспектива". Lit.lib.ru. Retrieved 2017-08-21.

- ↑ "Официальный сайт Постоянного представительства Республики Северная Осетия-Алания при Президенте РФ. Осетины в Москве". Noar.ru. Archived from the original on 1 May 2009. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ↑ Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for. "Refworld - The North Caucasian Diaspora In Turkey". Unhcr.org. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ↑ Национальный состав, владение языками и гражданство населения республики таджикистан (PDF). Statistics of Tajikistan (in Russian and Tajik). Statistics of Tajikistan. p. 9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

- ↑ "Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989 года. Национальный состав населения по республикам СССР". Archived from the original on 6 January 2012. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- ↑ "2001 Ukrainian census". Ukrcensus.gov.ua. Retrieved 2017-08-21.

- ↑ "Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989 года. Национальный состав населения по республикам СССР". Archived from the original on 3 January 2012. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- ↑ "Итоги всеобщей переписи населения Туркменистана по национальному составу в 1995 году". Archived from the original on 2013-03-13. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- ↑ "Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989 года. Национальный состав населения по республикам СССР". Archived from the original on 4 January 2012. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- ↑ "Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989 года. Национальный состав населения по республикам СССР". Archived from the original on 7 January 2012. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- ↑ "First Ethnic Ossetian Refugees from Syria Arrive in North Ossetia". Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- ↑ Национальный статистический комитет Республики Беларусь (PDF). Национальный статистический комитет Республики Беларусь (in Russian). Национальный статистический комитет Республики Беларусь. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 18, 2013. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ↑ "Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989 года. Национальный состав населения по республикам СССР". Archived from the original on 25 January 2016. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- ↑ "Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989 года. Национальный состав населения по республикам СССР". Archived from the original on 4 January 2012. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- ↑ "Latvijas iedzīvotāju sadalījums pēc nacionālā sastāva un valstiskās piederības (Datums=01.07.2017)" (PDF) (in Latvian). Retrieved 8 February 2017.

- ↑ "Lietuvos Respublikos 2011 metų visuotinio gyventojų ir būstų surašymo rezultatai". p. 8. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- ↑ "2000 Estonian census". Pub.stat.ee. Retrieved 2017-08-21.

- ↑ Bell, Imogen (2003). Eastern Europe, Russia and Central Asia. London: Taylor & Francis. p. 200.

- ↑ Mirsky, Georgiy I. (1997). On Ruins of Empire: Ethnicity and Nationalism in the Former Soviet Union. p. 28.

- ↑ Mastyugina, Tatiana. An Ethnic History of Russia: Pre-revolutionary Times to the Present. p. 80.

- 1 2 Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. (1991). "The New Encyclopaedia Britannica: Marcopædia". Encyclopædia Britannica. 22. p. 625. ISBN 9780852295298.

Ossetic is not mutually intelligible with any other Iranian language.

- ↑ Minahan, James (1998). Miniature Empires: A Historical Dictionary of the Newly Independent States. New York City, NY: Routledge. p. 211. ISBN 1-57958-133-1.

- 1 2 Shnirelman, Victor (2006). "The Politics of a Name: Between Consolidation and Separation in the Northern Caucasus" (PDF). Acta Slavica Iaponica. 23: 37–49.

- ↑ "Map image". S23.postimg.org. Archived from the original (JPG) on 2017-02-05. Retrieved 2017-08-21.

- ↑ "Map image" (JPG). S50.radikal.ru. Retrieved 2017-08-21.

- ↑ Lora Arys-Djanaïéva "Parlons ossète" (Harmattan, 2004)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Ossetians". Encarta. Microsoft Corporation. 2008.

- ↑ James Minahan, "One Europe, Many Nations", Published by Greenwood Publishing Group, 2000. pg 518: "The Ossetians, calling themselves Iristi and their homeland Iryston are the most northerly Iranian people. ... They are descended from a division of Sarmatians, the Alans who were pushed out of the Terek River lowlands and in the Caucasus foothills by invading Huns in the 4th century AD.

- ↑ "Getting Back Home? Towards Sustainable Return of Ingush Forced Migrants and Lasting Peace in Prigorodny District of North Ossetia" (PDF). Pdc.ceu.hu. Retrieved 2017-08-21.

- ↑ "Ca-c.org". Ca-c.org. Retrieved 2017-08-21.

- ↑ Svante E. Cornell, Small nations and great powers: a study of ethnopolitical conflict in the Caucasus. Routledge, 2001 ISBN 0-7007-1162-7

- ↑ "South Ossetia – MSN Encarta". Archived from the original on 2009-11-01. Retrieved 2009-10-28.

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ "Arena: Atlas of Religions and Nationalities in Russia". Sreda, 2012.

- ↑ 2012 Arena Atlas Religion Maps. "Ogonek", № 34 (5243), 27/08/2012. Retrieved 21/04/2017. Archived.

- ↑ "Михаил Рощин : Религиозная жизнь Южной Осетии: в поисках национально-культурной идентификации". Keston.org.uk. Retrieved 2017-08-21.

- ↑ Arena - Atlas of Religions and Nationalities in Russia. Sreda.org

- ↑ "DataLife Engine > Версия для печати > Местная религиозная организация традиционных верований осетин "Ǽцǽг Дин" г. Владикавказ". Osetins.com. Retrieved 2017-08-21.

- ↑ Kuznetsov, Vladimir Alexandrovitch. "Alania and Byzantine". The History of Alania.

- ↑ James Stuart Olson, Nicholas Charles Pappas. An Ethnohistorical dictionary of the Russian and Soviet empires. Greenwood Publishing Group, 1994. p 522.

- ↑ Ronald Wixman. The peoples of the USSR: an ethnographic handbook. M.E. Sharpe, 1984. p 151

- ↑ James Minahan. Miniature empires: a historical dictionary of the newly independent states. Greenwood Publishing Group, 1998. p.211

- ↑ Nasidze, I; Quinque, D; Dupanloup, I; et al. (November 2004). "Genetic evidence concerning the origins of South and North Ossetians". Ann. Hum. Genet. 68: 588–99. doi:10.1046/j.1529-8817.2004.00131.x. PMID 15598217.

Bibliography

- Nasidze; et al. (May 2004). "Mitochondrial DNA and Y-Chromosome Variation in the Caucasus". Annals of Human Genetics. 68: 205. doi:10.1046/j.1529-8817.2004.00092.x.

- Nasidze; et al. (2004). "Genetic Evidence Concerning the Origins of South and North Ossetians" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-01-12. Retrieved 2006-11-01.