Indian Ocean

| Indian Ocean | |

|---|---|

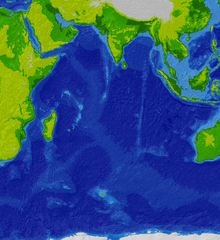

Extent of the Indian Ocean according to The World Factbook | |

| Location | South Asia, Southeast Asia, Western Asia, Northeast Africa, East Africa, Southern Africa and Australia |

| Coordinates | 20°S 80°E / 20°S 80°ECoordinates: 20°S 80°E / 20°S 80°E |

| Type | Ocean |

| Max. width | 6,200 mi (10,000 km) |

| Surface area | 70,560,000 km2 (27,240,000 sq mi) |

| Average depth | 3,741 m (12,274 ft) |

| Max. depth | 7,906 m (25,938 ft) |

|

| Earth's oceans |

|---|

|

World Ocean |

The Indian Ocean is the third largest of the world's oceanic divisions, covering 70,560,000 km2 (27,240,000 sq mi) (approximately 20% of the water on the Earth's surface).[1] It is bounded by Asia on the north, on the west by Africa, on the east by Australia, and on the south by the Southern Ocean or, depending on definition, by Antarctica.[2] It is named after India.[3][4]

Etymology

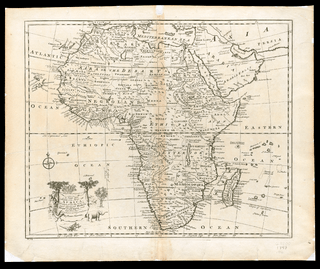

The Indian Ocean was earlier known as the Eastern Ocean,[3] or Eastern Sea. The term was still in use during the mid-18th century.

Geography

_in_Antiquity_-_Geographicus_-_ErythraeanSea-jansson-1658.jpg)

The borders of the Indian Ocean, as delineated by the International Hydrographic Organization in 1953 included the Southern Ocean but not the marginal seas along the northern rim, but in 2000 the IHO delimited the Southern Ocean separately, which removed waters south of 60°S from the Indian Ocean, but included the northern marginal seas.[5][6] Meridionally, the Indian Ocean is delimited from the Atlantic Ocean by the 20° east meridian, running south from Cape Agulhas, and from the Pacific Ocean by the meridian of 146°55'E, running south from the southernmost point of Tasmania. The northernmost extent of the Indian Ocean is approximately 30° north in the Persian Gulf.

The Indian Ocean covers 70,560,000 km2 (27,240,000 sq mi), including the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf but excluding the Southern Ocean, or 19.5% of the world's oceans; its volume is 264,000,000 km3 (63,000,000 cu mi) or 19.8% of the world's oceans' volume; it has an average depth of 3,741 m (12,274 ft) and a maximum depth of 7,906 m (25,938 ft).[7]

The ocean's continental shelves are narrow, averaging 200 kilometres (120 mi) in width. An exception is found off Australia's western coast, where the shelf width exceeds 1,000 kilometres (620 mi). The average depth of the ocean is 3,890 m (12,762 ft). Its deepest point is Diamantina Deep in Diamantina Trench, at 8,047 m (26,401 ft) deep; Sunda Trench has a depth of 7,258–7,725 m (23,812–25,344 ft). North of 50° south latitude, 86% of the main basin is covered by pelagic sediments, of which more than half is globigerina ooze. The remaining 14% is layered with terrigenous sediments. Glacial outwash dominates the extreme southern latitudes.

The major choke points include Bab el Mandeb, Strait of Hormuz, the Lombok Strait, the Strait of Malacca and the Palk Strait. Seas include the Gulf of Aden, Andaman Sea, Arabian Sea, Bay of Bengal, Great Australian Bight, Laccadive Sea, Gulf of Mannar, Mozambique Channel, Gulf of Oman, Persian Gulf, Red Sea and other tributary water bodies. The Indian Ocean is artificially connected to the Mediterranean Sea through the Suez Canal, which is accessible via the Red Sea. All of the Indian Ocean is in the Eastern Hemisphere and the centre of the Eastern Hemisphere is in this ocean.

Marginal seas

Marginal seas, gulfs, bays and straits of the Indian Ocean include:

- Andaman Sea

- Arabian Sea

- Bay of Bengal

- Great Australian Bight

- Gulf of Mannar

- Gulf of Aden

- Gulf of Aqaba

- Gulf of Tadjoura

- Gulf of Bahrain

- Gulf of Carpentaria

- Gulf of Kutch

- Gulf of Khambat

- Gulf of Oman

- Indonesian Seaway (including the Malacca, Sunda and Torres Straits)

- Laccadive Sea

- Mozambique Channel

- Palk Strait connecting Arabian Sea and Bay of Bengal

- Persian Gulf

- Red Sea

- Guardafui Channel

- Sea of Zanj

- Strait of Bab-el-Mandeb connecting Arabian Sea

- Strait of Hormuz connecting Persian Gulf

Climate

The climate north of the equator is affected by a monsoon climate. Strong north-east winds blow from October until April; from May until October south and west winds prevail. In the Arabian Sea the violent Monsoon brings rain to the Indian subcontinent. In the southern hemisphere, the winds are generally milder, but summer storms near Mauritius can be severe. When the monsoon winds change, cyclones sometimes strike the shores of the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal.

The Indian Ocean is the warmest ocean in the world. Long-term ocean temperature records show a rapid, continuous warming in the Indian Ocean, at about 0.7–1.2 °C (1.3–2.2 °F) during 1901–2012.[8] Indian Ocean warming is the largest among the tropical oceans, and about 3 times faster than the warming observed in the Pacific. Research indicates that human induced greenhouse warming, and changes in the frequency and magnitude of El Niño events are a trigger to this strong warming in the Indian Ocean.[8]

Oceanography

Among the few large rivers flowing into the Indian Ocean are the Zambezi, Shatt al-Arab, Indus, Godavari, Krishna, Narmada, Ganges, Brahmaputra, Jubba and Irrawaddy. The ocean's currents are mainly controlled by the monsoon. Two large gyres, one in the northern hemisphere flowing clockwise and one south of the equator moving anticlockwise (including the Agulhas Current and Agulhas Return Current), constitute the dominant flow pattern. During the winter monsoon, however, currents in the north are reversed.

Deep water circulation is controlled primarily by inflows from the Atlantic Ocean, the Red Sea, and Antarctic currents. North of 20° south latitude the minimum surface temperature is 22 °C (72 °F), exceeding 28 °C (82 °F) to the east. Southward of 40° south latitude, temperatures drop quickly.

Precipitation and evaporation leads to salinity variation in all oceans, and in the Indian Ocean salinity variations are driven by: (1) river inflow mainly from the Bay of Bengal, (2) fresher water from the Indonesian Throughflow; and (3) saltier water from the Red Sea and Persian Gulf.[9] Surface water salinity ranges from 32 to 37 parts per 1000, the highest occurring in the Arabian Sea and in a belt between southern Africa and south-western Australia. Pack ice and icebergs are found throughout the year south of about 65° south latitude. The average northern limit of icebergs is 45° south latitude.

Geology

As the youngest of the major oceans,[10] the Indian Ocean has active spreading ridges that are part of the worldwide system of mid-ocean ridges. In the Indian Ocean these spreading ridges meet at the Rodrigues Triple Point with the Central Indian Ridge, including the Carlsberg Ridge, separating the African Plate from the Indian Plate; the Southwest Indian Ridge separating the African Plate from the Antarctic Plate; and the Southeast Indian Ridge separating the Australian Plate from the Antarctic Plate. The Central Ridge runs north on the in-between across of the Arabian Peninsula and Africa into the Mediterranean Sea.

A series of ridges and seamount chains produced by hotspots pass over the Indian Ocean. The Réunion hotspot (active 70–40 million years ago) connects Réunion and the Mascarene Plateau to the Chagos-Laccadive Ridge and the Deccan Traps in north-western India; the Kerguelen hotspot (100–35 million years ago) connects the Kerguelen Islands and Kerguelen Plateau to the Ninety East Ridge and the Rajmahal Traps in north-eastern India; the Marion hotspot (100–70 million years ago) possibly connects Prince Edward Islands to the Eighty Five East Ridge.[11] These hotspot tracks have been broken by the still active spreading ridges mentioned above.

Marine life

Among the tropical oceans, the western Indian Ocean hosts one of the largest concentration of phytoplankton blooms in summer, due to the strong monsoon winds. The monsoonal wind forcing leads to a strong coastal and open ocean upwelling, which introduces nutrients into the upper zones where sufficient light is available for photosynthesis and phytoplankton production. These phytoplankton blooms support the marine ecosystem, as the base of the marine food web, and eventually the larger fish species. The Indian Ocean accounts for the second largest share of the most economically valuable tuna catch.[12] Its fish are of great and growing importance to the bordering countries for domestic consumption and export. Fishing fleets from Russia, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan also exploit the Indian Ocean, mainly for shrimp and tuna.[13]

Research indicates that increasing ocean temperatures are taking a toll on the marine ecosystem. A study on the phytoplankton changes in the Indian Ocean indicates a decline of up to 20% in the marine phytoplankton in the Indian Ocean, during the past six decades. The tuna catch rates have also declined abruptly during the past half century, mostly due to increased industrial fisheries, with the ocean warming adding further stress to the fish species.[14]

Endangered marine species include the dugong, seals, turtles, and whales.[13]

An Indian Ocean garbage patch was discovered in 2010 covering at least 5 million square kilometres (1.9 million square miles). Riding the southern Indian Ocean Gyre, this vortex of plastic garbage constantly circulates the ocean from Australia to Africa, down the Mozambique Channel, and back to Australia in a period of six years, except for debris that get indefinitely stuck in the centre of the gyre.

In 2016, UK researchers from Southampton University identified six new animal species at hydrothermal vents beneath the Indian Ocean. These new species were a "Hoff" crab, a "giant peltospirid" snail, a whelk-like snail, a limpet, a scaleworm and a polychaete worm.[15]

History

First settlements

The history of the Indian Ocean is marked by maritime trade; cultural and commercial exchange probably date back at least seven thousand years.[16] During this period, independent, short-distance oversea communications along its littoral margins have evolved into an all-embracing network. The début of this network was not the achievement of a centralised or advanced civilisation but of local and regional exchange in the Persian Gulf, the Red Sea, and Arabian Sea. Sherds of Ubaid (2500–500 BCE) pottery have been found in the western Gulf at Dilmun, present-day Bahrain; traces of exchange between this trading centre and Mesopotamia. Sumerian traded grain, pottery, and bitumen (used for reed boats) for copper, stone, timber, tin, dates, onions, and pearls.[17] Coast-bound vessels transported goods between the Harappa civilisation (2600–1900 BCE) in India (modern-day Pakistan and Gujarat in India) and the Persian Gulf and Egypt.[16]

Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, an Alexandrian guide to the world beyond the Red Sea — including Africa and India — from the first century CE, not only gives insights into trade in the region but also shows that Roman and Greek sailors had already gained knowledge about the monsoon winds.[16] The contemporaneous settlement of Madagascar by Indonesian sailors shows that the littoral margins of the Indian Ocean were being both well-populated and regularly traversed at least by this time. Albeit the monsoon must have been common knowledge in the Indian Ocean for centuries.[16]

The world's earliest civilizations in Mesopotamia (beginning with Sumer), ancient Egypt, and the Indian subcontinent (beginning with the Indus Valley civilization), which began along the valleys of the Tigris-Euphrates, Nile and Indus rivers respectively, all developed around the Indian Ocean. Civilizations soon arose in Persia (beginning with Elam) and later in Southeast Asia (beginning with Funan).

During Egypt's first dynasty (c. 3000 BCE), sailors were sent out onto its waters, journeying to Punt, thought to be part of present-day Somalia. Returning ships brought gold and myrrh. The earliest known maritime trade between Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley (c. 2500 BC) was conducted along the Indian Ocean. Phoenicians of the late 3rd millennium BCE may have entered the area, but no settlements resulted.

The Indian Ocean's relatively calmer waters opened the areas bordering it to trade earlier than the Atlantic or Pacific oceans. The powerful monsoons also meant ships could easily sail west early in the season, then wait a few months and return eastwards. This allowed ancient Indonesian peoples to cross the Indian Ocean to settle in Madagascar around 1 CE.[18]

Era of discovery

In the 2nd or 1st century BCE, Eudoxus of Cyzicus was the first Greek to cross the Indian Ocean. The probably fictitious sailor Hippalus is said to have discovered the direct route from Arabia to India around this time.[19] During the 1st and 2nd centuries AD intensive trade relations developed between Roman Egypt and the Tamil kingdoms of the Cheras, Cholas and Pandyas in Southern India. Like the Indonesian peoples above, the western sailors used the monsoon to cross the ocean. The unknown author of the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea describes this route, as well as the commodities that were traded along various commercial ports on the coasts of the Horn of Africa and India circa 1 CE. Among these trading settlements were Mosylon and Opone on the Red Sea littoral.

Unlike the Pacific Ocean where the civilization of the Polynesians reached most of the far flung islands and atolls and populated them, almost all the islands, archipelagos and atolls of the Indian Ocean were uninhabited until colonial times. Although there were numerous ancient civilizations in the coastal states of Asia and parts of Africa, the Maldives were the only island group in the Central Indian Ocean region where an ancient civilization flourished.[20] Maldivian ships used the Indian Monsoon Current to travel to the nearby coasts.[21]

From 1405 to 1433 Admiral Zheng He led large fleets of the Ming Dynasty on several treasure voyages through the Indian Ocean, ultimately reaching the coastal countries of East Africa.[22]

In 1497 Portuguese navigator Vasco da Gama rounded the Cape of Good Hope and became the first European to sail to India and later the Far East. The European ships, armed with heavy cannon, quickly dominated trade. Portugal achieved pre-eminence by setting up forts at the important straits and ports. Their hegemony along the coasts of Africa and Asia lasted until the mid 17th century. Later, the Portuguese were challenged by other European powers. The Dutch East India Company (1602–1798) sought control of trade with the East across the Indian Ocean. France and Britain established trade companies for the area. From 1565 Spain established a major trading operation with the Manila Galleons in the Philippines and the Pacific. Spanish trading ships purposely avoided the Indian Ocean, following the Treaty of Tordesillas with Portugal. By 1815, Britain became the principal power in the Indian Ocean.

Industrial era

The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 revived European interest in the East, but no nation was successful in establishing trade dominance. Since World War II the United Kingdom was forced to withdraw from the area, to be replaced by India, the USSR, and the United States. The last two tried to establish hegemony by negotiating for naval base sites. Developing countries bordering the ocean, however, seek to have it made a "zone of peace" so that they may use its shipping lanes freely. The United Kingdom and United States maintain a military base on Diego Garcia atoll in the middle of the Indian Ocean.

Contemporary era

On 26 December 2004 the countries surrounding the Indian Ocean were hit by a tsunami caused by the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake. The waves resulted in more than 226,000 deaths and over 1 million people were left homeless.

In the late 2000s the ocean evolved into a hub of pirate activity. By 2013, attacks off the Horn region's coast had steadily declined due to active private security and international navy patrols, especially by the Indian Navy.[23]

Malaysian Airlines Flight 370, a Boeing 777 airliner with 239 persons on board, disappeared on 8 March 2014 and is alleged to have crashed into the southeastern Indian Ocean about 2,000km from the coast of southwest Western Australia. Despite an extensive search, the whereabouts of the remains of the aircraft are unknown.

Trade

The sea lanes in the Indian Ocean are considered among the most strategically important in the world with more than 80 percent of the world’s seaborne trade in oil transits through Indian Ocean and its vital choke points, with 40 percent passing through the Strait of Hormuz, 35 percent through the Strait of Malacca and 8 percent through the Bab el-Mandab Strait.[24]

The Indian Ocean provides major sea routes connecting the Middle East, Africa, and East Asia with Europe and the Americas. It carries a particularly heavy traffic of petroleum and petroleum products from the oil fields of the Persian Gulf and Indonesia. Large reserves of hydrocarbons are being tapped in the offshore areas of Saudi Arabia, Iran, India, and Western Australia. An estimated 40% of the world's offshore oil production comes from the Indian Ocean.[13] Beach sands rich in heavy minerals, and offshore placer deposits are actively exploited by bordering countries, particularly India, Pakistan, South Africa, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and Thailand.

Major ports and harbours

The Port of Singapore is the busiest port in the Indian Ocean, located in the Strait of Malacca where it meets the Pacific. Mumbai, Chennai, Kolkata, Kochi, Mormugao Port, Mundra, Port Blair, Visakhapatnam, Paradip, Ennore, and Tuticorin are the major Indian ports. South Asian ports include Chittagong in Bangladesh, Colombo, Hambantota and Galle in Sri Lanka, Chabahar in Iran and ports of Karachi, Sindh province and Gwadar, Balochistan province in Pakistan. Aden is a major port in Yemen and controls ships entering the Red Sea. Major African ports on the shores of the Indian Ocean include: Mombasa (Kenya), Dar es Salaam, Zanzibar (Tanzania), Durban, East London, Richard's Bay (South Africa), Beira (Mozambique), and Port Louis (Mauritius). Zanzibar is especially famous for its spice export. Other major ports in the Indian Ocean include Muscat (Oman), Yangon (Burma), Jakarta, Medan (Indonesia), Fremantle (port servicing Perth, Australia) and Dubai (UAE).

Chinese companies have made investments in several Indian Ocean ports, including Gwadar, Hambantota, Colombo and Sonadia. This has sparked a debate about the strategic implications of these investments.[25]

Bordering countries and territories

Small islands dot the continental rims. Island nations within the ocean are Madagascar (the world's fourth largest island), Bahrain, Comoros, Maldives, Mauritius, Seychelles and Sri Lanka. The archipelago of Indonesia and the island nation of East Timor border the ocean on the east.

Heading roughly clockwise, the states and territories (in italics) with a coastline on the Indian Ocean (including the Red Sea and Persian Gulf) are:

Africa

Asia

Australasia

Southern Indian Ocean

See also

References

- ↑ Rais, R. B. (1986). The Indian Ocean and the Superpowers. Routledge. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-7099-4241-2.

- ↑ "'Indian Ocean' — Merriam-Webster Dictionary Online". Retrieved 7 July 2012.

ocean E of Africa, S of Asia, W of Australia, & N of Antarctica area ab 73,427,795 square kilometres (28,350,630 sq mi)

- 1 2 Harper, Douglas. "Indian Ocean". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 18 January 2011.

- ↑ Harper, Douglas. "India". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- ↑ "Limits of Oceans and Seas" (PDF). Nature. 172 (4376): 484. 1953. Bibcode:1953Natur.172R.484.. doi:10.1038/172484b0. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- ↑ "The Indian Ocean and its sub-divisions". International Hydrographic Organization, Special Publication N°23. 2002. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- ↑ Eakins, B. W.; Sharman, G. F. (2010). "Volumes of the World's Oceans from ETOPO1". Boulder, CO: NOAA National Geophysical Data Center. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- 1 2 Roxy, Mathew Koll; Ritika, Kapoor; Terray, Pascal; Masson, Sébastien (2014-09-11). "The Curious Case of Indian Ocean Warming". Journal of Climate. 27 (22): 8501–8509. Bibcode:2014JCli...27.8501R. doi:10.1175/JCLI-D-14-00471.1. ISSN 0894-8755.

- ↑ Han, W.; McCreary Jr, J. P. (2001). "Modelling salinity distributions in the Indian Ocean" (PDF). Journal of Geophysical Research. 106 (C1): 859–877 (see Introduction, p. 859). Bibcode:2001JGR...106..859H. doi:10.1029/2000jc000316. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- ↑ Stow, D. A. V. (2006). Oceans: an illustrated reference. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 127 (Map of Indian Ocean). ISBN 978-0-226-77664-4.

- ↑ Müller, R. D.; Royer, J. Y.; Lawver, L. A. (1993). "Revised plate motions relative to the hotspots from combined Atlantic and Indian Ocean hotspot tracks" (PDF). Geology. 21 (3): 275–278 (Fig. 1, p. 275). Bibcode:1993Geo....21..275D. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1993)021<0275:rpmrtt>2.3.co;2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 July 2015. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- ↑ "Tuna fisheries and utilization". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2016. Retrieved 29 January 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Oceans: Indian Ocean". CIA – The World Factbook. 2015. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- ↑ Roxy, M. K. (2016). "A reduction in marine primary productivity driven by rapid warming over the tropical Indian Ocean". Geophysical Research Letters. 43 (2): 826–833. Bibcode:2016GeoRL..43..826R. doi:10.1002/2015GL066979.

- ↑ "New marine life found in deep sea vents". BBC News. 15 December 2016. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Alpers 2013, Chapter 1. Imagining the Indian Ocean, pp. 1–2

- ↑ Alpers 2013, Chapter 2. The Ancient Indian Ocean, pp. 19–22

- ↑ Fitzpatrick, S.; Callaghan, R. (2009). "Seafaring simulations and the origin of prehistoric settlers to Madagascar" (PDF). In Clark, G. R.; O'Connor, S.; Leach, B. F. Islands of Inquiry: Colonisation, Seafaring and the Archaeology of Maritime Landscapes. ANU E Press. pp. 47–58. ISBN 9781921313905. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- ↑ El-Abbadi, M. (2000). "The greatest emporium in the inhabited world". Coastal management sourcebooks 2. Paris: UNESCO.

- ↑ Cabrero, Ferran (2004). "Cultures del món: El desafiament de la diversitat" (PDF) (in Portuguese). UNESCO. p. 32–38 (Els maldivians: Mariners llegedaris). Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- ↑ Romero-Frias, Xavier (2016). "Rules for Maldivian Trading Ships Travelling Abroad (1925) and a Sojourn in Southern Ceylon". Politeja. 40: 69–84. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- ↑ Dreyer, E. L. (2007). Zheng He: China and the Oceans in the Early Ming Dynasty, 1405–1433. New York: Pearson Longman. p. 1.

- ↑ Arnsdorf, Isaac (22 July 2013). "West Africa Pirates Seen Threatening Oil and Shipping". Bloomberg. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ↑ DeSilva-Ranasinghe, Sergei (2011-03-02). "Why the Indian Ocean Matters". The Diplomat.

- ↑ Brewster, D. (2014). "Beyond the String of Pearls: Is there really a Security Dilemma in the Indian Ocean?". Journal of the Indian Ocean Region. 10 (2): 133–149. doi:10.1080/19480881.2014.922350. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

Sources

- Alpers, E. A. (2013). The Indian Ocean in World History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-533787-7. Lay summary.

External links

| Look up indian ocean in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

- "The Indian Ocean in World History" (Flash). Sultan Qaboos Cultural Center. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- "The Indian Ocean Trade: A Classroom Simulation" (PDF). African Studies Center, Boston University. Retrieved 25 July 2015.