Amur River

| Amur River | |

| ᠰᠠᡥᠠᠯᡳᠶᠠᠨ ᡠᠯᠠ sahaliyan ula (in Manchu) 黑龙江 Hēilóng Jiāng (in Chinese) Аму́р, Amur (in Russian) | |

Amur River (Heilong Jiang) | |

| Name origin: Mongolian: amur ("rest") | |

| Countries | Russia, China |

|---|---|

| Part of | Strait of Tartary |

| Tributaries | |

| - left | Shilka, Zeya, Bureya, Amgun |

| - right | Ergune, Huma, Songhua, Ussuri |

| Cities | Blagoveschensk, Heihe, Tongjiang, Khabarovsk, Amursk, Komsomolsk-on-Amur, Nikolayevsk-on-Amur |

| Primary source | Onon River-Shilka River |

| - location | Khan Khentii Strictly Protected Area, Khentii Province, Mongolia |

| - elevation | 2,045 m (6,709 ft) |

| - coordinates | 48°48′59″N 108°46′13″E / 48.81639°N 108.77028°E |

| Secondary source | Kherlen River-Ergune River |

| - location | about 195 kilometres (121 mi) from Ulaanbaatar, Khentii Province, Mongolia |

| - elevation | 1,961 m (6,434 ft) |

| - coordinates | 48°47′54″N 109°11′54″E / 48.79833°N 109.19833°E |

| Source confluence | |

| - location | Near Pokrovka, Russia & China |

| - elevation | 303 m (994 ft) |

| - coordinates | 53°19′58″N 121°28′37″E / 53.33278°N 121.47694°E |

| Mouth | Strait of Tartary |

| - location | Near Nikolaevsk-on-Amur, Khabarovsk Krai, Russia |

| - elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| - coordinates | 52°56′50″N 141°05′02″E / 52.94722°N 141.08389°ECoordinates: 52°56′50″N 141°05′02″E / 52.94722°N 141.08389°E |

| Length | 2,824 km (1,755 mi) [1] |

| Basin | 1,855,000 km2 (716,220 sq mi) [1] |

| Discharge | mouth |

| - average | 11,400 m3/s (402,587 cu ft/s) |

| - max | 30,700 m3/s (1,084,160 cu ft/s) |

| - min | 514 m3/s (18,152 cu ft/s) |

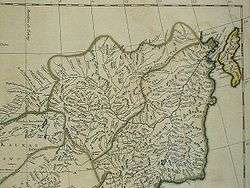

Map of the Amur River watershed | |

The Amur River (Even: Тамур, Tamur; Russian: река́ Аму́р, IPA: [ɐˈmur]) or Heilong Jiang (Chinese: 黑龙江; pinyin: Hēilóng Jiāng, "Black Dragon River"; Manchu: ᠰᠠᡥᠠᠯᡳᠶᠠᠨ

ᡠᠯᠠorᡥᡝᠯᡠᠩ

ᡤᡳᠶᠠᠩ[2]; Möllendorff: sahaliyan ula/helung giyang; Abkai: sahaliyan ula/helung giyang, "Black Water") is the world's tenth longest river, forming the border between the Russian Far East and Northeastern China (Inner Manchuria). The largest fish species in the Amur is the kaluga, attaining a length as great as 5.6 metres (18 ft).[3] The Amur River is the only river in the world in which subtropical Asian fish such as snakehead, coexist with Arctic Siberian fish, such as pike. The river is home to a variety of other large predatory fish such as Taimen, Amur Catfish, and yellowcheek.

Name

Historically, it was common to refer to a river simply as "water". The word for "water" is similar in a number of Asiatic languages: mul (물) in Korean, muren (mörön) in Mongolian, and mizu (みず) in Japanese. The name "Amur" may have evolved from a root word for water, coupled with a size modifier for "Big Water".[4]

The Chinese name for the river, Heilong Jiang, means Black Dragon River in Chinese, and its Mongolian name, Khar mörön (Cyrillic: Хар мөрөн), means Black River.[1]

Course

| Amur River | |||||||

| |||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 黑龍江 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 黑龙江 | ||||||

| Literal meaning | "Black Dragon River" | ||||||

| |||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 阿穆爾河 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 阿穆尔河 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Mongolian name | |||||||

| Mongolian | Хар Мөрөн / Амар Мөрөн | ||||||

| |||||||

| Manchu name | |||||||

| Manchu script |

ᠰᠠᡥᠠᠯᡳᠶᠠᠨ ᡠᠯᠠ | ||||||

| Romanization | Sahaliyan Ula | ||||||

| Russian name | |||||||

| Russian | Амур | ||||||

| Romanization | Amur | ||||||

The river rises in the hills in the western part of Northeast China at the confluence of its two major affluents, the Shilka River and the Ergune (or Argun) River, at an elevation of 303 metres (994 ft).[5] It flows east forming the border between China and Russia, and slowly makes a great arc to the southeast for about 400 kilometres (250 mi), receiving many tributaries and passing many small towns. At Huma, it is joined by a major tributary, the Huma River. Afterwards it continues to flow south until between the cities of Blagoveschensk (Russia) and Heihe (China), it widens significantly as it is joined by the Zeya River, one of its most important tributaries.

The Amur arcs to the east and turns southeast again at the confluence with the Bureya River, then does not receive another significant tributary for nearly 250 kilometres (160 mi) before its confluence with its largest tributary, the Songhua River, at Tongjiang. At the confluence with the Songhua the river turns northeast, now flowing towards Khabarovsk, where it joins the Ussuri River and ceases to define the Russia–China border. Now the river spreads out dramatically into a braided character, flowing north-northeast through a wide valley in eastern Russia, passing Amursk and Komsomolsk-on-Amur. The valley narrows after about 200 kilometres (120 mi) and the river again flows north onto plains at the confluence with the Amgun River. Shortly after, the Amur turns sharply east and into an estuary at Nikolayevsk-on-Amur, about 20 kilometres (12 mi) downstream of which it flows into the Strait of Tartary.

History and context

In many historical references these two geopolitical entities are known as Outer Manchuria (Russian Manchuria) and Inner Manchuria, respectively. The Chinese province of Heilongjiang on the south bank of the river is named after it, as is the Russian Amur Oblast on the north bank. The name Black River (sahaliyan ula) was used by the native Manchu people and their Qing Empire of China, who regarded this river as sacred.

The Amur River is an important symbol of, and geopolitical factor in, Chinese–Russian relations. The Amur was especially important in the period following the Sino–Soviet political split in the 1960s.

For many centuries the Amur Valley was populated by the Tungusic (Evenki, Solon, Ducher, Jurchen, Nanai, Ulch) and Mongol (Daur) people, and, near its mouth, by the Nivkhs. For many of them, fishing in the Amur and its tributaries was the main source of their livelihood. Until the 17th century, these people were not known to the Europeans, and little known to the Han Chinese, who sometimes collectively described them as the Wild Jurchens. The term Yupi Dazi ("Fish-skin Tatars") was used for the Nanais and related groups as well, owing to their traditional clothes made of fish skins.

The Mongols, ruling the region as the Yuan dynasty, established a tenuous military presence on the lower Amur in the 13–14th centuries; ruins of a Yuan-era temple have been excavated near the village of Tyr.[6]

During the Yongle and Xuande eras (early 15th century), the Ming dynasty reached the Amur as well in their drive to establish control over the lands adjacent to the Ming Empire to the northeast, which were later to become known as Manchuria. Expeditions headed by the eunuch Yishiha reached Tyr several times between 1411 and the early 1430s, re-building (twice) the Yongning Temple and obtaining at least the nominal allegiance of the lower Amur's tribes to the Ming government.[7][8] Some sources report also a Chinese presence during the same period on the middle Amur – a fort existed at Aigun for about 20 years during the Yongle era on the left (northwestern) shore of the Amur downstream from the mouth of the Zeya River. This Ming Dynasty Aigun was located on the opposite bank to the later Aigun that was relocated during the Qing Dynasty.[9] In any event, the Ming presence on the Amur was as short-lived as it was tenuous; soon after the end of the Yongle era, the Ming dynasty's frontiers retreated to southern Manchuria.

Chinese cultural and religious influence such as Chinese New Year, the "Chinese god", Chinese motifs like the dragon, spirals, scrolls, and material goods like agriculture, husbandry, heating, iron cooking pots, silk, and cotton spread among the Amur natives like the Udeghes, Ulchis, and Nanais.[10]

Russian Cossack expeditions led by Vassili Poyarkov and Yerofey Khabarov explored the Amur and its tributaries in 1643–44 and 1649–51, respectively. The Cossacks established the fort of Albazin on the upper Amur, at the site of the former capital of the Solons.

At the time, the Manchus were busy with conquering the region; but a few decades later, during the Kangxi era, they turned their attention to their north-Manchurian backyard. Aigun was reestablished near the supposed Ming site in about 1683–84, and a military expeditions was sent upstream to dislodge the Russians, whose Albazin establishment deprived the Manchu rulers from the tribute of sable pelts that the Solons and Daurs of the area would supply otherwise.[11] Albazin fell during a short military campaign in 1685. The hostilities were concluded in 1689 by the Treaty of Nerchinsk, which left the entire Amur valley, from the convergence of the Shilka and the Ergune downstream, in Chinese hands.

Fedor Soimonov was sent to map the then little explored area of the Amur in 1757. He mapped the Shilka, which was partly in Chinese territory, but was turned back when he reached its confluence with the Argun.[12] The Russian proselytization of Orthodox Christianity to the indigenous peoples along the Amur River was viewed as a threat by the Qing.[13]

The Amur region remained a relative backwater of the Qing Empire for the next century and a half, with Aigun being practically the only major town on the river. Russians re-appeared on the river in the mid-19th century, forcing the Manchus to yield all lands north of the river to the Russian Empire by the Treaty of Aigun (1858). Lands east of the Ussury and the lower Amur were acquired by Russia as well, by the Convention of Peking (1860).

The acquisition of the lands on the Amur and the Ussury was followed by the migration of Russian settlers to the region and the construction of such cities as Blagoveshchensk and, later, Khabarovsk.

Numerous river steamers, built in England, plied the Amur by the late 19th century. Tsar Nicolas II, then Tsarovitch, visited Vladivostok and then cruised up the river. Mining dredges were imported from America to work the placer gold of the river. Barge and river traffic was greatly hindered by the Civil War of 1918–22. The Soviet Reds had the Amur Flotilla which patrolled the river on sequestered riverboats. In the 1930s and during the War the Japanese had their own flotilla on the river. In 1945 the Soviets again put their own flotilla on the river. The ex-German Yangtse gunboats Vaterland and Otter, on Chinese Nationalist Navy service, patrolled the Amur in the 1920s.

Direction

Flowing across northeast Asia for over 4,444 kilometres (2,761 mi) (including its two attributaries), from the mountains of northeastern China to the Sea of Okhotsk (near Nikolayevsk-na-Amure), it drains a remarkable watershed that includes diverse landscapes of desert, steppe, tundra, and taiga, eventually emptying into the Pacific Ocean through the Strait of Tartary, where the mouth of the river faces the northern end of the island of Sakhalin.

The Amur has always been closely associated with the island of Sakhalin at its mouth, and most names for the island, even in the languages of the indigenous peoples of the region, are derived from the name of the river: "Sakhalin" derives from a Tungusic dialectal form cognate with Manchu sahaliyan ("black", as in sahaliyan ula, "Black River"), while Ainu and Japanese "Karaputo" or "Karafuto" is derived from the Ainu name of the Amur or its mouth. Anton Chekhov vividly described the Amur River in writings about his journey to Sakhalin Island in 1890.

The average annual discharge varies from 6,000 cubic metres per second (210,000 cu ft/s) (1980) to 12,000 cubic metres per second (420,000 cu ft/s) (1957), leading to an average 9,819 cubic metres per second (346,800 cu ft/s) or 310 cubic kilometres (74 cu mi) per year. The maximum runoff measured occurred in Oct 1951 with 30,700 cubic metres per second (1,080,000 cu ft/s) whereas the minimum discharge was recorded in March 1946 with a mere 514 cubic metres per second (18,200 cu ft/s).[14]

Bridges and tunnels

The first permanent bridge across the Amur, the Khabarovsk Bridge, elevation 2,590 metres (8,500 ft), was completed in 1916, allowing the trains on the Transsiberian Railway to cross the river year-round without using ferries or rail tracks on top of the river ice. In 1941 a railway tunnel was added as well.

Later, a combined road and rail bridge over the Amur at Komsomolsk-on-Amur (1975; 1400 m) and the road and rail Khabarovsk Bridge (1999; 3890 m) were constructed.

Amur Bridge Project

The Amur Bridge Project was proposed in 2007 by Valery Solomonovich Gurevich, the vice-chairman of the Jewish Autonomous Oblast in Russia. The railway bridge over the Amur River will connect Tongjiang with Nizhneleninskoye, a village in the Jewish Autonomous Oblast.[15]

The Chinese portion of the bridge was finished in July 2016.[16] In December 2016, work began on the Russian portion of the bridge. The bridge is expected to open in October 2019.[17]

See also

- Amuri, Tampere, a Tampere district named after battles at river Amur during the Russo-Japanese war

- Amur cork tree

- Amur falcon

- Amur leopard

- Amur tiger

- Amur honeysuckle

- Geography of China

- Geography of Russia

- Sino-Soviet border conflict

- Jilin chemical plant explosions 2005

- Home of the Kaluga (Acipenseriformes)

- List of longest undammed rivers

- Sixty-Four Villages East of the Heilong Jiang

- Amur Military Flotilla

References

- 1 2 3 Muranov, Aleksandr Pavlovich; Greer, Charles E.; Owen, Lewis. "Amur River". Encyclopædia Britannica (online ed.).

- ↑ Liaoning province's archive, Manchu Veritable Record Upper Vol《满洲实录上函/manju-i yargiyan kooli dergi dobton》

- ↑ C. Michael Hogan. 2012. Amur River. Encyclopedia of Earth. Archived November 30, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Topic ed. Peter Saundry

- ↑ Scheffel, Richard L.; Wernet, Susan J., eds. (1980). Natural Wonders of the World. United States of America: Reader's Digest Association, Inc. p. 43. ISBN 0-89577-087-3.

- ↑ Source elevation derived from Google Earth

- ↑ Головачев В. Ц. (V. Ts. Golovachev), «Тырские стелы и храм „Юн Нин“ в свете китайско-чжурчжэньских отношений XIV—XV вв.» Archived 2009-02-23 at the Wayback Machine. (The Tyr Stelae and the Yongning Temple viewed in the context of Sino-Jurchen relations of the 14-15th centuries) Этно-Журнал, 2008-11-14. (in Russian)

- ↑ L. Carrington Godrich, Chaoying Fang (editors), "Dictionary of Ming Biography, 1368–1644". Volume I (A-L). Columbia University Press, 1976. ISBN 0-231-03801-1

- ↑ Shih-Shan Henry Tsai, "Perpetual Happiness: The Ming Emperor Yongle". Published by University of Washington Press, 2002. ISBN 0-295-98124-5 Partial text on Google Books. pp. 158-159.

- ↑ Du Halde, Jean-Baptiste (1735). Description géographique, historique, chronologique, politique et physique de l'empire de la Chine et de la Tartarie chinoise. Volume IV. Paris: P.G. Lemercier. pp. 15–16. Numerous later editions are available as well, including one on Google Books. Du Halde refers to the Yongle-era fort, the predecessor of Aigun, as Aykom. There seem to be few, if any, mentions of this project in other available literature.

- ↑ Forsyth 1994, p. 214.

- ↑ Du Halde (1735), pp. 15-16

- ↑ Foust, Muscovite and Mandarin p. 245-250

- ↑ Kim 2012/2013, p. 169.

- ↑ "Amur at Komsomolsk". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 2012-08-12. Retrieved 2008-08-14.

- ↑ Proposed bridge to boost bilateral trade, China Daily, June 19, 2007.

- ↑ Andrew Higgins (July 16, 2016). "An Unfinished Bridge, and Partnership, Between Russia and China". The New York Times. Retrieved July 17, 2016.

- ↑ "Russia, China launch construction of bridge across Amur river". Russia Today. December 25, 2016.

- Bisher, Jamie (2006). White Terror: Cossack Warlords of the Trans-Siberian. Routledge. ISBN 1135765952. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Bisher, Jamie (2006). White Terror: Cossack Warlords of the Trans-Siberian. Routledge. ISBN 1135765960. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Forsyth, James (1994). A History of the Peoples of Siberia: Russia's North Asian Colony 1581-1990 (illustrated, reprint, revised ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521477719. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- KANG, HYEOKHWEON. Shiau, Jeffrey, ed. "Big Heads and Buddhist Demons: The Korean Military Revolution and Northern Expeditions of 1654 and 1658" (PDF). Emory Endeavors in World History (2013 ed.). 4: Transnational Encounters in Asia: 1–22. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 2013. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Kim 金, Loretta E. 由美 (2012–2013). "Saints for Shamans? Culture, Religion and Borderland Politics in Amuria from the Seventeenth to Nineteenth Centuries". Central Asiatic Journal. Harrassowitz Verlag. 56: 169–202. JSTOR 10.13173/centasiaj.56.2013.0169.

- Stephan, John J. (1996). The Russian Far East: A History (illustrated, reprint ed.). Stanford University Press. ISBN 0804727015. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

External links

![]()

- Amur-Heilong River Basin Information Center - maps, GIS data, environmental data

- Information and a map of the Amur’s watershed