Primary Chronicle

The Tale of Bygone Years (Old East Slavic: Повѣсть времѧньныхъ лѣтъ, Pověstĭ Vremęnĭnyhŭ Lětŭ) known in English-language historiography as the Primary Chronicle is a history of Kievan Rus' from about 850 to 1110, originally compiled in Kiev about 1113.[1] The work is considered to be a fundamental source in the interpretation of the history of the Eastern Slavs.

Three editions

First

Tradition long regarded the original compilation as the work of a monk named Nestor (c. 1056 – c. 1114); hence scholars spoke of Nestor's Chronicle or of Nestor's manuscript. His compilation has not survived. Nestor's many sources included

- the earlier but now lost Slavonic chronicles

- the Byzantine annals of John Malalas, a Greek chronicler, who in 563 produced an 18 book work of intertwined myth and truth

- the Byzantine annals of George Hamartolus, a monk, who tried to adhere strictly to truth, and whose works are the unique contemporary source for the period 813–842

- byliny,[3]:18 which were traditional East Slavic oral epic narrative poems

- Norse sagas[3]:43

- several Greek religious texts

- Rus'–Byzantine treaties

- oral accounts of Yan Vyshatich and of other military leaders.

Nestor worked at the court of Sviatopolk II of Kiev (ruled 1093–1113), and probably shared Sviatopolk's pro-Scandinavian policies.

The early part of the Chronicle features many anecdotal stories, among them

- those of the arrival of the three Varangian brothers,

- the founding of Kiev

- the murder of Askold and Dir, ca. 882

- the death of Oleg in 912, the "cause" of which was reported foreseen by him

- the thorough vengeance taken by Olga, the wife of Igor, on the Drevlians, who had murdered her husband;[4] (Her actions secured Kievan Rus' from the Drevlians, preventing her from having to marry a Drevlian prince, and allowing her to act as regent until her young son came of age.)

The account of the labors of Saints Cyril and Methodius among the Slavic peoples also makes a very interesting tale, and to Nestor we owe the story of the summary way in which Vladimir the Great (ruled 980 to 1015) suppressed the worship of Perun and other traditional gods at Kiev.[3]:116

Second

In the year 1116, Nestor's text was extensively edited by the hegumen Sylvester who appended his name at the end of the chronicle. As Vladimir Monomakh was the patron of the village of Vydubychi (now a neighborhood of Kiev) where Sylvester's monastery was situated, the new edition glorified Vladimir and made him the central figure of later narrative.[3]:17 This second version of Nestor's work is preserved in the Laurentian codex (see below).

Third

A third edition followed two years later and centered on the person of Vladimir's son and heir, Mstislav the Great. The author of this revision could have been Greek, for he corrected and updated much data on Byzantine affairs. This latest revision of Nestor's work is preserved in the Hypatian codex (see below).

Two manuscripts

Because the original of the chronicle as well as the earliest known copies are lost, it is difficult to establish the original content of the chronicle. The two main sources for the chronicle's text as it is known presently are the Laurentian Codex and the Hypatian Codex.

The Laurentian Codex was compiled in what are today Russian lands by the Nizhegorod monk Laurentius for the Prince Dmitry Konstantinovich in 1377. The original text he used was a codex (since lost) compiled for the Grand Duke Mikhail of Tver in 1305. The account continues until 1305, but the years 898–922, 1263–83 and 1288–94 are missing for reasons unknown. The manuscript was acquired by the famous Count Musin-Pushkin in 1792 and subsequently presented to the National Library of Russia in Saint Petersburg.

The Hypatian Codex dates to the 15th century. It was written in what are today Ukrainian lands and incorporates much information from the lost 12th-century Kievan and 13th-century Halychian chronicles.[5] The language of this work is the East Slavic version of Church Slavonic language with many additional irregular east-slavisms (like other east-Slavic codices of the time). Whereas the Laurentian (Muscovite) text traces the Kievan legacy through to the Muscovite princes, the Hypatian text traces the Kievan legacy through the rulers of the Halych principality. The Hypatian codex was rediscovered in Kiev in the 1620s, and a copy was made for Prince Kostiantyn Ostrozhsky. A copy was found in Russia in the 18th century at the Ipatiev Monastery of Kostroma by the Russian historian Nikolai Karamzin.

Numerous monographs and published versions of the chronicle have been made, the earliest known being in 1767. Aleksey Shakhmatov published a pioneering textological analysis of the narrative in 1908. Dmitry Likhachev and other Soviet scholars partly revisited his findings. Their versions attempted to reconstruct the pre-Nestorian chronicle, compiled at the court of Yaroslav the Wise in the mid-11th century.

Assessment

Unlike many other medieval chronicles written by European monks, the Tale of Bygone Years is unique as the only written testimony on the earliest history of East Slavic people.[3]:23 Its comprehensive account of the history of Rus' is unmatched in other sources, although important correctives are provided by the Novgorod First Chronicle.[6] It is also valuable as a prime example of the Old East Slavonic literature.[3]:3

See also

References

- ↑ "The Tale of Bygone Years– Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine".

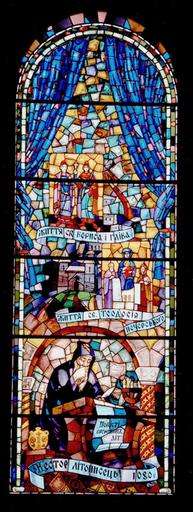

- ↑ "Mol, Leo" (PDF).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Cross, Samuel Hazzard; Sherbowitz-Wetzor, Olgerd P. (translators & editors) The Russian Primary Chronicle, Laurentian Text. The Mediaeval Academy of America, Cambridge, Maschusetts, 1930 & 1953.

- ↑ Hubbs, Joanna. Mother Russia, The Feminine Myth in Russian Culture. Indiana University Press, Bloomington and Indianapolis, 1988, page 88

- ↑ "Chronicles– Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine".

- ↑ Zenkovsky, Serge A.: Medieval Russia’s epics, chronicles, and tales. A Meridian Book, Penguin Books, New York, 1963, page 77

Further reading

- Chadwick, Nora Kershaw (1946). The Beginnings of Russian History: An Enquiry into Sources. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-404-14651-1.

- Velychenko, Stephen (1992). National history as cultural process: A survey of the interpretations of Ukraine's past in Polish, Russian, and Ukrainian historical writing from the earliest times to 1914. Edmonton. ISBN 0-920862-75-6.

- Velychenko, Stephen (2007). "Nationalizing and Denationalizing the Past. Ukraine and Russia in Comparative Context". Ab Imperio (1).

External links

Transcription of original texts

- "Лаврентьевская летопись" [The Laurentian Chronicle.], Полное собрание русских летописей (ПСРЛ) (online edition) (in Russian), USSR Academy of Sciences, 1, 1928 , from the Laurentian Codex

- "Ипатьевская летопись" [Ipatiev Chronicle], Полное собрание русских летописей (ПСРЛ) (in Russian), Imperial Archaeological Commission, 2, 1908 , from the Hypatian Codex

- Новгородская первая летопись старшего и младшего изводов [Novogorod Chronicle ..] (in Russian), USSR Academy of Sciences, 1950 , from the Novgorod Codex

- Ostrowski, Donald (ed.), Povest' vremennykh let (in Russian and scholarship and analysis in English) , includes an interlinear collation including the five main manuscript witnesses, as well as a new paradosis, or reconstruction of the original.

Translations

- "Laurentian Codex 1377" (in Church Slavonic; Russian). National Library of Russia. 2012. , digitisation of the Laurentian Codex, including transliteration and translation into modern Russian, with an introduction in english

- Hazzard Cross, Samuel; Sherbowitz-Wetzor, Olgerd, eds. (1953) [1377]. The Russian Primary chronicle: Laurentian text (in English translation). The Mediaeval Academy of America.

- Excerpts from "Tales of Times Gone By" [Povest' vremennykh let] (Lecture Notes), University of Oregon