Aksai Chin

Coordinates: 35°7′N 79°8′E / 35.117°N 79.133°E

| Aksai Chin | |||||||

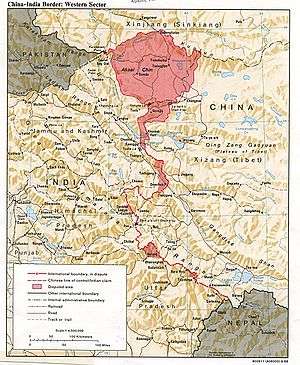

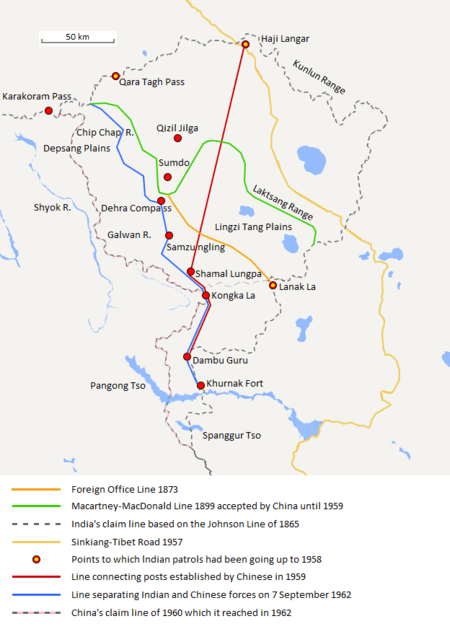

India–China border, showing Aksai Chin | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 阿克賽欽 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 阿克赛钦 | ||||||

| |||||||

Aksai Chin (Chinese: 阿克赛钦; pinyin: Ākèsài Qīn; Uyghur: ﺋﺎﻗﺴﺎﻱ ﭼﯩﻦ ;Hindi-अक्साई चिन) is a disputed border area between China and India. It is administered by China as part of Hotan County, which lies in the southwestern part of Hotan Prefecture of Xinjiang Autonomous Region, but is also claimed by India as a part of the Ladakh region of the state of Jammu and Kashmir. In 1962, China and India fought a brief war in Aksai Chin and Arunachal Pradesh, but in 1993 and 1996, the two countries signed agreements to respect the Line of Actual Control.[1]

Name

The etymology of Aksai Chin is uncertain regarding the word "chin". As a word of Turkic origin, aksai literally means "white brook" but whether the word chin refers to Chinese or pass is disputed. The Chinese name of the region, 阿克赛钦, is composed of Chinese characters chosen for their phonetic values,[2] irrespective of their meaning.

Geography

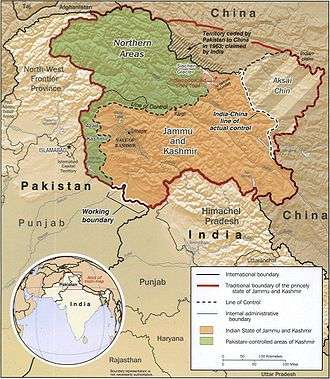

Aksai Chin is one of the two large disputed border areas between India and China. India claims Aksai Chin as the easternmost part of the Jammu and Kashmir state. China claims that Aksai Chin is part of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. The line that separates Indian-administered areas of Jammu and Kashmir from Aksai Chin is known as the Line of Actual Control (LAC) and is concurrent with the Chinese Aksai Chin claim line.

Aksai Chin covers an area of about 37,244 square kilometres (14,380 sq mi). The area is largely a vast high-altitude desert with a low point (on the Karakash River) at about 4,300 m (14,100 ft) above sea level. In the southwest, mountains up to 7,000 m (23,000 ft) extending southeast from the Depsang Plains form the de facto border (Line of Actual Control) between Aksai Chin and Indian-controlled Kashmir.

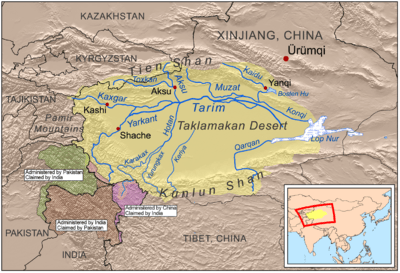

In the north, the Kunlun Range separates Aksai Chin from the Tarim Basin, where the rest of Hotan County is situated. According to a recent detailed Chinese map, no roads cross the Kunlun Range within Hotan Prefecture, and only one track does so, over the Hindutash Pass.[3]

Aksai Chin area has number of endorheic basins with many salt or soda lakes. The major salt lakes are Surigh yil ganning kol, Tso tang, Aksai Chin Lake, Hongshan hu, etc. Much of the northern part of Aksai Chin is referred to as the Soda Plains, located near Aksai Chin's largest river, the Karakash, which receives meltwater from a number of glaciers, crosses the Kunlun farther northwest, in Pishan County and enters the Tarim Basin, where it serves as one of the main sources of water for Karakax and Hotan Counties.

The western part of Aksai Chin region is drained by the Tarim River. The eastern part of the region contains several small endorheic basins. The largest of them is that of the Aksai Chin Lake, which is fed by the river of the same name. The region as a whole receives little precipitation as the Himalayas and the Karakoram block the rains from the Indian monsoon.

People

Besides officials from the Chinese military, the inhabitants of Aksai Chin are, for the most part, members of nomadic groups such as the Bakarwal who regularly pass through the area.[4] The best known settlements are the town of Tianshuihai and the village of Tielongtan.

History

Because of its 5,000 metres (16,000 ft) elevation, the desolation of Aksai Chin meant that it had no human importance other than as an ancient trade route, which provided a temporary pass during summer for caravans of yaks between Xinjiang and Tibet.[5] For military campaigns, the region held great importance, as it was on the only route from Tarim Basin to Tibet that was passable all year round. The Dzungar Khanate used this route to enter Tibet in 1717[6].

One of the earliest treaties regarding the boundaries in the western sector was signed in 1842. Ladakh was conquered a few years earlier by the armies of Raja Gulab Singh (Dogra) under the suzerainty of the Sikh Empire. Following an unsuccessful campaign into Tibet in 1840, Gulab Singh and the Tibetans signed a treaty, agreeing to stick to the "old, established frontiers", which were left unspecified.[7][8] The British defeat of the Sikhs in 1846 resulted in the transfer of the Jammu and Kashmir region including Ladakh to the British, who then installed Gulab Singh as the Maharaja under their suzerainty. British commissioners contacted Chinese officials to negotiate the border, who did not show any interest.[9] The British boundary commissioners fixed the southern end of the boundary at Pangong Lake, but regarded the area north of it as terra incognita.[10] [11]

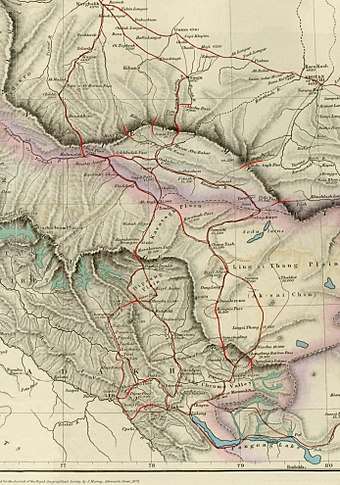

The Johnson Line

William Johnson, a civil servant with the Survey of India proposed the "Johnson Line" in 1865, which put Aksai Chin in Kashmir.[12] This was the time of the Dungan revolt, when China did not control most of Xinjiang, so this line was never presented to the Chinese.[12] Johnson presented this line to the Maharaja of Kashmir, who then claimed the 18,000 square kilometres contained within,[12] and by some accounts territory further north as far as the Sanju Pass in the Kun Lun Mountains. Johnson's work was severely criticized for gross inaccuracies, with description of his boundary as "patently absurd".[13] Johnson was reprimanded by the British Government and resigned from the Survey.[12][13][14] The Maharajah of Kashmir constructed a fort at Shahidulla (modern-day Xaidulla), and had troops stationed there for some years to protect caravans.[15] Eventually, most sources placed Shahidulla and the upper Karakash River firmly within the territory of Xinjiang (see accompanying map). According to Francis Younghusband, who explored the region in the late 1880s, there was only an abandoned fort and not one inhabited house at Shahidulla when he was there - it was just a convenient staging post and a convenient headquarters for the nomadic Kirghiz.[16] The abandoned fort had apparently been built a few years earlier by the Kashmiris.[17] In 1878 the Chinese had reconquered Xinjiang, and by 1890 they already had Shahidulla before the issue was decided.[12] By 1892, China had erected boundary markers at Karakoram Pass.[13]

In 1897 a British military officer, Sir John Ardagh, proposed a boundary line along the crest of the Kun Lun Mountains north of the Yarkand River.[15] At the time Britain was concerned at the danger of Russian expansion as China weakened, and Ardagh argued that his line was more defensible. The Ardagh line was effectively a modification of the Johnson line, and became known as the "Johnson-Ardagh Line".

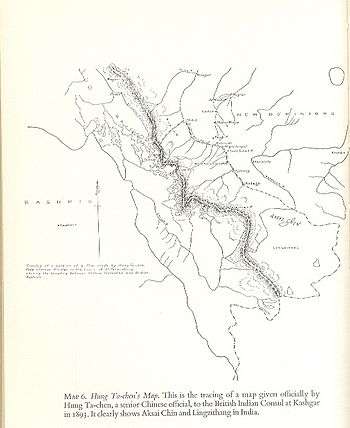

The Macartney–Macdonald Line

In 1893, Hung Ta-chen, a senior Chinese official at St. Petersburg, gave maps of the region to George Macartney, the British consul general at Kashgar, which coincided in broad details.[18]:pp. 73, 78 In 1899, Britain proposed a revised boundary, initially suggested by Macartney and developed by the Governor General of India Lord Elgin. This boundary placed the Lingzi Tang plains, which are south of the Laktsang range, in India, and Aksai Chin proper, which is north of the Laktsang range, in China. This border, along the Karakoram Mountains, was proposed and supported by British officials for a number of reasons. The Karakoram Mountains formed a natural boundary, which would set the British borders up to the Indus River watershed while leaving the Tarim River watershed in Chinese control, and Chinese control of this tract would present a further obstacle to Russian advance in Central Asia.[14] The British presented this line, known as the Macartney–MacDonald Line, to the Chinese in 1899 in a note by Sir Claude MacDonald. The Qing government did not respond to the note, and the British took that as Chinese acquiescence.[12] Although no official boundary had ever been negotiated, China believed that this had been the accepted boundary.[1][19]

1899 to 1947

Both the Johnson-Ardagh and the Macartney-MacDonald lines were used on British maps of India.[12] Until at least 1908, the British took the Macdonald line to be the boundary,[20] but in 1911, the Xinhai Revolution resulted in the collapse of central power in China, and by the end of World War I, the British officially used the Johnson Line. However they took no steps to establish outposts or assert actual control on the ground.[13] In 1927, the line was adjusted again as the government of British India abandoned the Johnson line in favor of a line along the Karakoram range further south.[13] However, the maps were not updated and still showed the Johnson Line.[13]

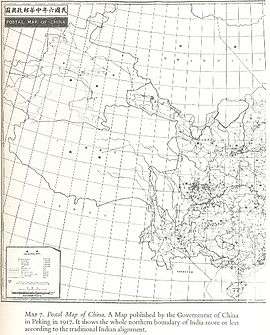

From 1917 to 1933, the Postal Atlas of China, published by the Government of China in Peking had shown the boundary in Aksai Chin as per the Johnson line, which runs along the Kunlun mountains.[18][19] The Peking University Atlas, published in 1925, also put the Aksai Chin in India.[21] When British officials learned of Soviet officials surveying the Aksai Chin for Sheng Shicai, warlord of Xinjiang in 1940-1941, they again advocated the Johnson Line.[12] At this point the British had still made no attempts to establish outposts or control over the Aksai Chin, nor was the issue ever discussed with the governments of China or Tibet, and the boundary remained undemarcated at India's independence.[12][13]

Since 1947

Upon independence in 1947, the government of India used the Johnson Line as the basis for its official boundary in the west, which included the Aksai Chin.[13] From the Karakoram Pass (which is not under dispute), the Indian claim line extends northeast of the Karakoram Mountains through the salt flats of the Aksai Chin, to set a boundary at the Kunlun Mountains, and incorporating part of the Karakash River and Yarkand River watersheds. From there, it runs east along the Kunlun Mountains, before turning southwest through the Aksai Chin salt flats, through the Karakoram Mountains, and then to Panggong Lake.[5]

On 1 July 1954 Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru wrote a memo directing that the maps of India be revised to show definite boundaries on all frontiers. Up to this point, the boundary in the Aksai Chin sector, based on the Johnson Line, had been described as "undemarcated."[14]

During the 1950s, the People's Republic of China built a 1,200 km (750 mi) road connecting Xinjiang and western Tibet, of which 179 km (112 mi) ran south of the Johnson Line through the Aksai Chin region claimed by India.[5][12][13] Aksai Chin was easily accessible to the Chinese, but was more difficult for the Indians on the other side of the Karakorams to reach.[5] The Indians did not learn of the existence of the road until 1957, which was confirmed when the road was shown in Chinese maps published in 1958.[22]

The Indian position, as stated by Prime Minister Nehru, was that the Aksai Chin was "part of the Ladakh region of India for centuries" and that this northern border was a "firm and definite one which was not open to discussion with anybody".[5]

The Chinese minister Zhou Enlai argued that the western border had never been delimited, that the Macartney-MacDonald Line, which left the Aksai Chin within Chinese borders was the only line ever proposed to a Chinese government, and that the Aksai Chin was already under Chinese jurisdiction, and that negotiations should take into account the status quo.[5]

Trans Karakoram Tract

The Johnson Line is not used west of the Karakoram Pass, where China adjoins Pakistan-administered Gilgit–Baltistan. On 13 October 1962, China and Pakistan began negotiations over the boundary west of the Karakoram Pass. In 1963, the two countries settled their boundaries largely on the basis of the Macartney-MacDonald Line, which left the Trans Karakoram Tract in China, although the agreement provided for renegotiation in the event of a settlement of the Kashmir dispute. India does not recognise that Pakistan and China have a common border, and claims the tract as part of the domains of the pre-1947 state of Kashmir and Jammu. However, India's claim line in that area does not extend as far north of the Karakoram Mountains as the Johnson Line.[5]

Strategic importance

China National Highway 219 runs through Aksai Chin connecting Lazi and Xinjiang in the Tibet Autonomous Region. Despite this region being nearly uninhabitable and having no resources, it remains strategically important for China as it connects Tibet and Xinjiang. Construction started in 1951 and the road was completed in 1957. The construction of this highway was one of the triggers for the Sino-Indian War of 1962. The repavement of the highway taken up for first time in about 50 years was completed in 2013.[23]

Chinese terrain model

In June 2006, satellite imagery on the Google Earth service revealed a 1:500[24] scale terrain model of eastern Aksai Chin and adjacent Tibet, built near the town of Huangyangtan, about 35 kilometres (22 mi) southwest of Yinchuan, the capital of the autonomous region of Ningxia in China.[25] A visual side-by-side comparison shows a very detailed duplication of Aksai Chin in the camp.[26] The 900 m × 700 m (3,000 ft × 2,300 ft) model was surrounded by a substantial facility, with rows of red-roofed buildings, scores of olive-colored trucks and a large compound with elevated lookout posts and a large communications tower. Such terrain models are known to be used in military training and simulation, although usually on a much smaller scale.

Local authorities in Ningxia claim that their model of Aksai Chin is part of a tank training ground, built in 1998 or 1999.[24]

See also

References

- 1 2 "India-China Border Dispute". GlobalSecurity.org.

- ↑ All these characters can be seen in Chinese Wikipedia's standard transcription table for foreign names, which in its turn is based on the standard transcription guide, 世界人名翻译大辞典 (The Great Dictionary of Foreign Personal Names' Translations), 1993, ISBN 7-5001-0221-6 (first edition); 1997, ISBN 7-5001-0799-4 (revised edition)

- ↑ Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region Road Atlas (中国分省公路丛书:新疆维吾尔自治区), published by 星球地图出版社 Xingqiu Ditu Chubanshe, 2008, ISBN 978-7-80212-469-1. Map of Hotan Prefecture, pp. 18-19.

- ↑ Chandran, D. Suba; Singh, Bhavna (2015-10-21). India, China and Sub-regional Connectivities in South Asia. SAGE Publications India. ISBN 9789351503262.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Maxwell, Neville, India's China War, New York, Pantheon, 1970.

- ↑ Gaver, John W. (2011). Protracted Contest: Sino-Indian Rivalry in the Twentieth Century. University of Washington Press. p. 83. ISBN 0295801204.

- ↑ Maxwell, India's China War 1970, p. 24.

- ↑ The Sino-Indian Border Disputes, by Alfred P. Rubin, The International and Comparative Law Quarterly, Vol. 9, No. 1. (Jan. 1960), pp. 96–125, JSTOR 756256.

- ↑ Maxwell, India's China War 1970, p. 25–26.

- ↑ Maxwell, India's China War 1970, p. 26.

- ↑ Guruswamy, Mohan; Singh, Zorawar Daulet (2009), "The Legacy of the Great Game" (PDF), India China Relations: The Border Issue and Beyond, Viva Books, ISBN 978-81-309-1195-3

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Mohan Guruswamy, Mohan, "The Great India-China Game", Rediff, 23 June 2003.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Calvin, James Barnard (April 1984). "The China-India Border War". Marine Corps Command and Staff College. Retrieved 2011-10-14.

- 1 2 3 Noorani, A.G. (30 August – 12 September 2003), "Fact of History", Frontline, Madras: The Hindu group, vol. 26 no. 18, archived from the original on 2 October 2011, retrieved 24 August 2011

- 1 2 Woodman, Dorothy (1969). Himalayan Frontiers. Barrie & Rockcliff. pp. 101 and 360ff.

- ↑ Younghusband, Francis E. (1896). The Heart of a Continent. John Murray, London. Facsimile reprint: (2005) Elbiron Classics, pp. 223-224.

- ↑ Grenard, Fernand (1904). Tibet: The Country and its Inhabitants. Fernand Grenard. Translated by A. Teixeira de Mattos. Originally published by Hutchison and Co., London. 1904. Reprint: Cosmo Publications. Delhi. 1974, pp. 28-30.

- 1 2 3 Woodman, Dorothy (1969). Himalayan Frontiers. London: Barrie & Rockliff, The Cresset Press.

- 1 2 Verma, Virendra Sahai (2006). "Sino-Indian Border Dispute At Aksai Chin - A Middle Path For Resolution" (PDF). Journal of development alternatives and area studies. 25 (3): 6–8. ISSN 1651-9728. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ↑ Woodman (1969), p.79

- ↑ Fisher, Margaret W.; Rose, Leo E.; Huttenback, Robert A. (1963). Himalayan Battleground: Sino-Indian Rivalry in Ladakh. Praeger. p. 101 – via Questia. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ China's Decision for War with India in 1962 by John W. Garver Archived 26 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Ying, Li (24 September 2014). "A road from n the sky". Global Times.

- 1 2 "Chinese X-file not so mysterious after all". Melbourne: The Age. 2006-07-23. Archived from the original on 13 January 2009. Retrieved 2008-12-17.

- ↑ "From sky, see how China builds model of Indian border 2400 km away".

- ↑ Google Earth Community posting, 10 April 2007

Bibliography

- Maxwell, Neville (1970), India's China War, Pantheon Books, ISBN 978-0-394-47051-1

External links

- China and Kashmir, by Jabin T. Jacob, published in The Future of Kashmir, special issue of ACDIS Swords and Ploughshares, Program in Arms Control, Disarmament, and International Security, University of Illinois, winter 2007-8.

- Conflict in Kashmir: Selected Internet Resources by the Library, University of California, Berkeley, USA; University of California, Berkeley Library Bibliographies and Web-Bibliographies list

- Two maps of Kashmir: maps showing the Indian and Pakistani positions on the border.