Persian Gulf

| Persian Gulf خلیج فارس (Persian) | |

|---|---|

Persian Gulf from space | |

| Location | Western Asia |

| Coordinates | Coordinates: 26°N 52°E / 26°N 52°E |

| Type | Gulf |

| Primary inflows | Sea of Oman |

| Basin countries | Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Bahrain, United Arab Emirates and Oman (exclave of Musandam) |

| Max. length | 989 km (615 mi) |

| Surface area | 251,000 km2 (97,000 sq mi) |

| Average depth | 50 m (160 ft) |

| Max. depth | 90 m (300 ft) |

The Persian Gulf (Persian: خلیج فارس, translit. Xalij-e Fârs, lit. 'Gulf of Fars'), (Arabic: الخليج الفارسي) is a mediterranean sea in Western Asia. The body of water is an extension of the Indian Ocean (Gulf of Oman) through the Strait of Hormuz and lies between Iran to the northeast and the Arabian Peninsula to the southwest.[1] The Shatt al-Arab river delta forms the northwest shoreline.

The Persian Gulf was a battlefield of the 1980–1988 Iran–Iraq War, in which each side attacked the other's oil tankers. It is the namesake of the 1991 Gulf War, the largely air- and land-based conflict that followed Iraq's invasion of Kuwait.

The gulf has many fishing grounds, extensive reefs (mostly rocky, but also coral), and abundant pearl oysters, but its ecology has been damaged by industrialization and oil spills.

The body of water is historically and internationally known as the "Persian Gulf".[2][3][4] Some Arab governments refer to it as the "Arabian Gulf" (Arabic: الخليج العربي, translit. Al-Khalīj al-ˁArabī) or "The Gulf",[5] but neither term is recognized internationally. The name "Gulf of Iran (Persian Gulf)" is used by the International Hydrographic Organization.[6]

The Persian Gulf resides in the Persian Gulf Basin, which is of Cenozoic origin and related to the subduction of the Arabian Plate under the Zagros Mountains.[7] The current flooding of the basin started 15 000 years ago due to rising sea levels of the Holocene glacial retreat.[8]

Geography

This inland sea of some 251,000 square kilometres (96,912 sq mi) is connected to the Gulf of Oman in the east by the Strait of Hormuz; and its western end is marked by the major river delta of the Shatt al-Arab, which carries the waters of the Euphrates and the Tigris. Its length is 989 kilometres (615 miles), with Iran covering most of the northern coast and Saudi Arabia most of the southern coast. The Persian Gulf is about 56 km (35 mi) wide at its narrowest, in the Strait of Hormuz. The waters are overall very shallow, with a maximum depth of 90 metres (295 feet) and an average depth of 50 metres (164 feet).

Countries with a coastline on the Persian Gulf are (clockwise, from the north): Iran; Oman's Musandam exclave; the United Arab Emirates; Saudi Arabia (in Iran this is called "Arvand Rood", where "Rood" means "river"); Qatar, on a peninsula off the Saudi coast; Bahrain, on an island; Kuwait; and Iraq in the northwest. Various small islands also lie within the Persian Gulf, some of which are the subject of territorial disputes between the states of the region.

Extent

The International Hydrographic Organization defines the Persian Gulf's southern limit as "The Northwestern limit of Gulf of Oman". This limit is defined as "A line joining Ràs Limah (25°57'N) on the coast of Arabia and Ràs al Kuh (25°48'N) on the coast of Iran (Persia)".[6]

Oceanography

The gulf is connected to Indian Ocean through Strait of Hormuz. Writing the water balance budget for the Persian Gulf, the inputs are river discharges from Iran and Iraq (estimated to be 2000 cubic meters per second), as well as precipitation over the sea which is around 180mm/year in Qeshm Island. The evaporation of the sea is high, so that after considering river discharge and rain contributions, there is still a deficit of 416 cubic kilometers per year.[9] This difference is supplied by currents at the Strait of Hormuz. The water from the Gulf has a higher salinity, and therefore exits from the bottom of the Strait, while ocean water with less salinity flows in through the top. Another study revealed the following numbers for water exchanges for the Gulf: evaporation = -1.84m/year, precipitation = 0.08m/year, inflow from the Strait = 33.66m/year, outflow from the Strait = -32.11m/year, and the balance is 0m/year.[10] Data from different 3D computational fluid mechanics models, typically with spatial resolution of 3 kilometers and depth each element equal to 1–10 meters are predominantly used in computer models.

Oil and gas

The Persian Gulf and its coastal areas are the world's largest single source of crude oil, and related industries dominate the region. Safaniya Oil Field, the world's largest offshore oilfield, is located in the Persian Gulf. Large gas finds have also been made, with Qatar and Iran sharing a giant field across the territorial median line (North Field in the Qatari sector; South Pars Field in the Iranian sector). Using this gas, Qatar has built up a substantial liquefied natural gas (LNG) and petrochemical industry.

In 2002, the Persian Gulf nations of Bahrain, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE produced about 25% of the world's oil, held nearly two-thirds of the world's crude oil reserves, and about 35% of the world's natural gas reserves.[11][12] The oil-rich countries (excluding Iraq) that have a coastline on the Persian Gulf are referred to as the Persian Gulf States. Iraq's egress to the gulf is narrow and easily blockaded consisting of the marshy river delta of the Shatt al-Arab, which carries the waters of the Euphrates and the Tigris rivers, where the east bank is held by Iran.

Name

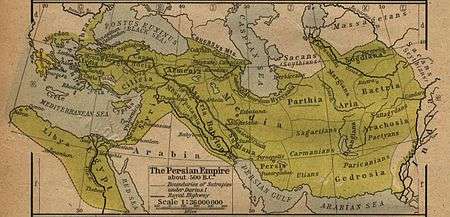

In 550 BC, the Achaemenid Empire established the first ancient empire in Persis (Pars, or modern Fars), in the southwestern region of the Iranian plateau. Consequently, in the Greek sources, the body of water that bordered this province came to be known as the "Persian Gulf".[13]

During the years 550 to 330 BC, coinciding with the sovereignty of the Achaemenid Persian Empire over the Middle East area, especially the whole part of the Persian Gulf and some parts of the Arabian Peninsula, the name of "Pars Sea" is widely found in the compiled written texts.[1]

In the travel account of Pythagoras, several chapters are related to description of his travels accompanied by the Achaemenid king Darius the Great, to Susa and Persepolis, and the area is described. From among the writings of others in the same period, there is the inscription and engraving of Darius the Great, installed at junction of waters of Red Sea and the Nile river and the Rome river (current Mediterranean) which belongs to the 5th century BC where Darius the Great has named the Persian Gulf Water Channel: "Pars Sea" ("Persian Sea").[1]

Considering the historical background of the name Persian Gulf, Sir Arnold Wilson mentions in a book published in 1928 that "no water channel has been so significant as Persian Gulf to the geologists, archaeologists, geographers, merchants, politicians, excursionists, and scholars whether in past or in present. This water channel which separates the Iran Plateau from the Arabia Plate, has enjoyed an Iranian Identity since at least 2200 years ago."[1]

Before being given its present name, the Persian Gulf was called many different names. The classical Greek writers, like Herodotus, called it "the Red Sea". In Babylonian texts, it was known as "the sea above Akkad".

Naming dispute

The name of the gulf, historically and internationally known as the Persian Gulf after the land of Persia (Iran), has been disputed by some Arab countries since the 1960s.[16] Rivalry between Iran and some Arab states, along with the emergence of pan-Arabism and Arab nationalism, has seen the name Arabian Gulf become predominant in most Arab countries.[17][18] Names beyond these two have also been applied to or proposed for this body of water.

History

Ancient history

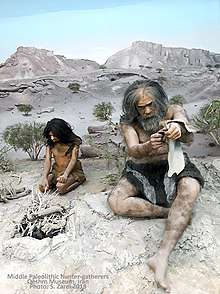

Earliest evidence of human presence on Persian Gulf islands dates back to Middle Paleolithic and consist of stone tools discovered at Qeshm Island[19].The world's oldest known civilization (Sumer) developed along the Persian Gulf and southern Mesopotamia. The shallow basin that now underlies the Gulf was an extensive region of river valley and wetlands during the transition between the end of the Last Glacial Maximum and the start of the Holocene, which, according to University of Birmingham archaeologist Jeffrey Rose, served as an environmental refuge for early humans during periodic hyperarid climate oscillations, laying the foundations for the legend of Dilmun.[20]

For most of the early history of the settlements in the Persian Gulf, the southern shores were ruled by a series of nomadic tribes. During the end of the fourth millennium BC, the southern part of the Persian Gulf was dominated by the Dilmun civilization. For a long time the most important settlement on the southern coast of the Persian Gulf was Gerrha. In the 2nd century the Lakhum tribe, who lived in what is now Yemen, migrated north and founded the Lakhmid Kingdom along the southern coast. Occasional ancient battles took place along the Persian Gulf coastlines, between the Sassanid Persian empire and the Lakhmid Kingdom, the most prominent of which was the invasion led by Shapur II against the Lakhmids, leading to Lakhmids' defeat, and advancement into Arabia, along the southern shore lines.[21] During the 7th century the Sassanid Persian empire conquered the whole of the Persian Gulf, including southern and northern shores.

Between 625 BC and 226 AD, the northern side was dominated by a succession of Persian empires including the Median, Achaemenid, Seleucid and Parthian empires. Under the leadership of the Achaemenid king Darius the Great (Darius I), Persian ships found their way to the Persian Gulf.[22] Persian naval forces laid the foundation for a strong Persian maritime presence in Persian Gulf, that started with Darius I and existed until the arrival of the British East India Company, and the Royal Navy by mid-19th century AD. Persians were not only stationed on islands of the Persian Gulf, but also had ships often of 100 to 200 capacity patrolling empire's various rivers including Shatt-al-Arab, Tigris, and the Nile in the west, as well as Sind waterway, in India.[22]

The Achaemenid high naval command had established major naval bases located along Shatt al-Arab river, Bahrain, Oman, and Yemen. The Persian fleet would soon not only be used for peacekeeping purposes along the Shatt al-Arab but would also open the door to trade with India via Persian Gulf.[22][23]

Following the fall of Achaemenid Empire, and after the fall of the Parthian Empire, the Sassanid empire ruled the northern half and at times the southern half of the Persian Gulf. The Persian Gulf, along with the Silk Road, were important trade routes in the Sassanid empire. Many of the trading ports of the Persian empires were located in or around Persian Gulf. Siraf, an ancient Sassanid port that was located on the northern shore of the gulf, located in what is now the Iranian province of Bushehr, is an example of such commercial port. Siraf, was also significant in that it had a flourishing commercial trade with China by the 4th century, having first established connection with the far east in 185 AD.[24]

Colonial era

Portuguese expansion into the Indian Ocean in the early 16th century following Vasco da Gama's voyages of exploration saw them battle the Ottomans up the coast of the Persian Gulf. In 1521, a Portuguese force led by commander Antonio Correia invaded Bahrain to take control of the wealth created by its pearl industry. On April 29, 1602, Shāh Abbās, the Persian emperor of the Safavid Persian Empire expelled the Portuguese from Bahrain,[25] and that date is commemorated as National Persian Gulf day in Iran.[26] With the support of the British fleet, in 1622 'Abbās took the island of Hormuz from the Portuguese; much of the trade was diverted to the town of Bandar 'Abbās, which he had taken from the Portuguese in 1615 and had named after himself. The Persian Gulf was therefore opened by Persians to a flourishing commerce with the Portuguese, Dutch, French, Spanish and the British merchants, who were granted particular privileges. The Ottoman Empire reasserted itself into Eastern Arabia in 1871.[27] Under military and political pressure from the governor of the Ottoman Vilayet of Baghdad, Midhat Pasha, the ruling Al Thani tribe submitted peacefully to Ottoman rule.[28] The Ottomans were forced to withdraw from the area with the start of World War I and the need for troops in various other frontiers.[29]

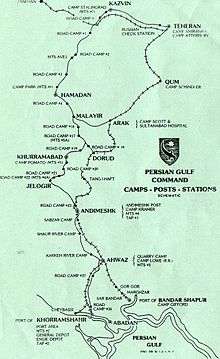

In World War II, the Western Allies used Iran as a conduit to transport military and industrial supply to the USSR, through a pathway known historically as the "Persian Corridor". Britain utilized the Persian Gulf as the entry point for the supply chain in order to make use of the Trans-Iranian Railway.[30] The Persian Gulf therefore became a critical maritime path through which the Allies transported equipment to Russia against the Nazi invasion.[31]

From 1763 until 1971, the British Empire maintained varying degrees of political control over some of the Persian Gulf states, including the United Arab Emirates (originally called the Trucial States)[32][33] and at various times Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, and Qatar through the British Residency of the Persian Gulf.

The United Kingdom maintains a high profile in the region to date; in 2006 alone, over 1 million British nationals visited Dubai.[34][35] In 2014, the UK announced it will reestablish a permanent military base, HMS Jufair, in the Persian Gulf, the first since it withdrew from East of Suez in 1971.[36][37][38]

Islands

The Persian Gulf is home to many small islands. Bahrain, an island in the Persian Gulf, is itself a Persian Gulf Arab state. Geographically the biggest island in the Persian Gulf is Qeshm island located in the Strait of Hormuz and belonging to Iran. Other significant islands in the Persian Gulf include Greater Tunb, Lesser Tunb and Kish administered by Iran, Bubiyan administered by Kuwait, Tarout administered by Saudi Arabia, and Dalma administered by UAE. In recent years, there has also been addition of artificial islands, often created by Arab states such as UAE for commercial reasons or as tourist resorts. Persian Gulf islands are often also historically significant, having been used in the past by colonial powers such as the Portuguese and the British in their trade or as acquisitions for their empires.[39]

Cities and population

Eight nations have coasts along the Persian Gulf: Bahrain, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates. The gulf's strategic location has made it an ideal place for human development over time. Today, many major cities of the Middle East are located in this region.

Wildlife

The wildlife of the Persian Gulf is diverse, and entirely unique due to the gulf's geographic distribution and its isolation from the international waters only breached by the narrow Strait of Hormuz. The Persian Gulf has hosted some of the most magnificent marine fauna and flora, some of which are near extirpation or at serious environmental risk. From corals, to dugongs, Persian Gulf is a diverse cradle for many species who depend on each other for survival. However, the gulf is not as biologically diverse as the Red Sea.[40]

Overall, the wild life of the Persian Gulf is endangered from both global factors, and regional, local negligence. Most pollution is from ships; land generated pollution counts as the second most common source of pollution.[41]

Aquatic mammals

Along the mediterranean regions of the Arabian Sea, including the Persian Gulf, the Red Sea, the Gulf of Kutch, the Gulf of Suez, the Gulf of Aqaba, the Gulf of Aden, and the Gulf of Oman, dolphins and finless porpoises are the most common marine mammals in the waters, while larger whales and orcas are rarer today.[42] Historically, whales had been abundant in the gulf before commercial hunts wiped them out.[43][44] Whales were reduced even further by illegal mass hunts by the Soviet Union and Japan in the 1960s and 1970s.[45] Along with Bryde's whales,[46][47][48][49] these once common residents can still can be seen in deeper marginal seas such as Gulf of Aden,[50] Israel coasts,[51] and in the Strait of Hormuz.[52] Other species such as the critically endangered Arabian humpback whale,[53] (also historically common in Gulf of Aden[54] and increasingly sighted in the Red Sea since 2006, including in the Gulf of Aqaba),[51] omura's whale,[55][56] minke whale, and orca also swim into the gulf, while many other large species such as blue whale,[57] sei,[58] and sperm whales were once migrants into the Gulf of Oman and off the coasts in deeper waters,[59] and still migrate into the Red Sea,[60] but mainly in deeper waters of outer seas. In 2017, waters of the Persian Gulf along Abu Dhabi were revealed to hold the world's largest population of Indo-Pacific humpbacked dolphins.[61][62][63]

One of the more unusual marine mammals living in the Persian Gulf is the dugong (Dugong dugon). Also called "sea cows", for their grazing habits and mild manner resembling livestock, dugongs have a life expectancy similar to that of humans and they can grow up to 3 metres (9.8 feet) in length. These gentle mammals feed on sea grass and are closer relatives of certain land mammals than are dolphins and whales.[64] Their simple grass diet is negatively affected by new developments along the Persian Gulf coastline, particularly the construction of artificial islands by Arab states and pollution from oil spills caused during the "Persian Gulf war" and various other natural and artificial causes. Uncontrolled hunting has also had a negative impact on the survival of dugongs.[64] After Australian waters, which are estimated to contain some 80,000 dugong inhabitants, the waters off Qatar, Bahrain, UAE, and Saudi Arabia make the Persian Gulf the second most important habitat for the species, hosting some 7,500 remaining dugongs. However, the current number of dugongs is dwindling and it is not clear how many are currently alive or what their reproductive trend is.[64][65] Unfortunately, ambitious and uncalculated construction schemes, political unrest, ever-present international conflict, the most lucrative world supply of oil, and the lack of cooperation between Arab states and Iran, have had a negative impact on the survival of many marine species, including dugongs.

Birds

The Persian Gulf is also home to many migratory and local birds. There is great variation in color, size, and type of the bird species that call the gulf home. One bird in particular, the kalbaensis subspecies of the collared kingfishers is at the brink of extinction due to real state development by cities such as Dubai and countries such as Oman.[66] Estimates from 2006 showed that only three viable nesting sites were available for this ancient bird, one located 80 miles (129 km) from Dubai, and two smaller sites in Oman, all of which are in the process of becoming real estate developments.[66] Such expansion would prove devastating and could cause this species to become extinct. Unfortunately for the kingfisher, a U.N. plan to protect the mangroves as a biological reserve was blatantly ignored by the emirate of Sharjah, which allowed the dredging of a channel that bisects the wetland and construction of an adjacent concrete walkway.[66] Environmental watchdogs in Arabia are few, and those that do advocate the wildlife are often silenced or ignored by developers of real estate, most of whom have royal family connections and huge energy profits to invest.[66] The end result has been sacrifice of a beautiful yet delicate ecology that has been in harmony for hundreds of years, for structures that are erected only a few years, yet will have a lasting detrimental effect.

Almost no species in the Persian Gulf is spared from the real estate development of UAE and Oman, including the hawksbill turtle, greater flamingo, and booted warbler, mainly due to destruction of the mangrove habitats to make way for towers, hotels, and luxury resorts.[66][67] Even dolphins that frequent the gulf in northern waters, around Iran are at serious risk. Recent statistics and observations show that dolphins are at danger of entrapment in purse seine fishing nets and exposure to chemical pollutants; perhaps the most alarming sign is the "mass suicides" committed by dolphins off Iran's Hormozgan province, which are not well understood, but are suspected to be linked with a deteriorating marine environment from water pollution from oil, sewage, and industrial run offs.[68][69]

Fish and reefs

The Persian Gulf is home to over 700 species of fish, most of which are native.[70] Of these 700 species, more than 80% are reef associated.[70] These reefs are primarily rocky, but there are also a few coral reefs. Compared to the Red Sea, the coral reefs in the Persian Gulf are relatively few and far between.[71][72][73] This is primarily connected to the influx of major rivers, especially the Shatt al-Arab (Euphrates and Tigris), which carry large amounts of sediment (most reef-building corals require strong light) and causes relatively large variations in temperature and salinity (corals in general are poorly suited to large variations).[71][72][73] Nevertheless, coral reefs have been found along sections of coast of all countries in the Gulf.[73] Corals are vital ecosystems that support multitude of marine species, and whose health directly reflects the health of the gulf. Recent years have seen a drastic decline in the coral population in the gulf, partially owing to global warming but majorly due to irresponsible dumping by Arab states like the UAE and Bahrain.[74] Construction garbage such as tires, cement, and chemical by products have found their way to the Persian Gulf in recent years. Aside from direct damage to the coral, the construction waste creates "traps" for marine life in which they are trapped and die.[74] The end result has been a dwindling population of the coral, and as a result a decrease in number of species that rely on the corals for their survival.

Flora

A great example of this symbiosis are the mangroves in the gulf, which require tidal flow and a combination of fresh and salt water for growth, and act as nurseries for many crabs, small fish, and insects; these fish and insects are the source of food for many of the marine birds that feed on them.[66] Mangroves are a diverse group of shrubs and trees belonging to the genus Avicennia or Rhizophora that flourish in the salt water shallows of the gulf, and are the most important habitats for small crustaceans that dwell in them. They are as crucial an indicator of biological health on the surface of the water, as the corals are to biological health of the gulf in deeper waters. Mangroves' ability to survive the salt water through intricate molecular mechanisms, their unique reproductive cycle, and their ability to grow in the most oxygen-deprived waters have allowed them extensive growth in hostile areas of the gulf.[75][76] Unfortunately, however, with the advent of artificial island development, most of their habitat is destroyed, or occupied by man-made structures. This has had a negative impact on the crustaceans that rely on the mangrove, and in turn on the species that feed on them.

Gallery

Dugong mother and her offspring in shallow water.

Dugong mother and her offspring in shallow water. Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins off the southern shore of Iran, around Hengam Island.

Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins off the southern shore of Iran, around Hengam Island.- Spinner dolphins leaping in the gulf.

Critically endangered Arabian humpback whales (being the most isolated, and the only resident population in the world) off Dhofar.

Critically endangered Arabian humpback whales (being the most isolated, and the only resident population in the world) off Dhofar.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names Working Paper No. 61, 23rd Session, Vienna, 28 March – 4 April 2006. accessed October 9, 2010

- ↑ Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). "The World Fact Book". Archived from the original on 2012-02-03. Retrieved 2010-12-04.

- ↑ nationsonline.org. "Political Map of Iran". Retrieved 2010-12-04.

- ↑ United Nations. "United Nations Cartographic Section (Middle East Map)".

- ↑ Niusha Boghrati, Omission of 'Persian Gulf' Name Angers Iran, World Press.com, December 28, 2006

- 1 2 "Limits of Oceans and Seas, 3rd edition" (PDF). International Hydrographic Organization. 1953. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- ↑ A Brief Tectonic History of the Arabian basin. Retrieved from the website: http://www.sepmstrata.org/page.aspx?pageid=133

- ↑ "A hot survivor". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2016-04-14.

- ↑ Pous, Stéphane; Lazure, Pascal; Carton, Xavier (2015). "A model of the general circulation in the Persian Gulf and in the Strait of Hormuz: Intraseasonal to interannual variability". Continental Shelf Research. 94: 55–70. doi:10.1016/j.csr.2014.12.008.

- ↑ Xue, Pengfei; Eltahir, Elfatih A. B. (2015-01-29). "Estimation of the Heat and Water Budgets of the Persian (Arabian) Gulf Using a Regional Climate Model". Journal of Climate. 28 (13): 5041–5062. doi:10.1175/JCLI-D-14-00189.1. ISSN 0894-8755.

- ↑ Persian Gulf Online. "Persian Gulf Oil and Gas Exports Fact Sheet (U.S. Department of Energy)". Archived from the original on July 14, 2009. Retrieved March 4, 2011.

- ↑ U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). "Persian Gulf Oil and Gas Export Fact Sheet". EIA/DOE (Energey Information Administration/Department of Energy). Archived from the original on January 2, 2011.

- ↑ Touraj Daryaee (2003). "The Persian Gulf Trade in Late Antiquity". Journal of World History. 14 (1). Archived from the original on August 5, 2013.

- ↑ K Darbandi (Oct 27, 2007). "Gulf renamed in aversion to 'Persian'". Asia Times. Retrieved 2010-11-30.

- ↑ Mahan Abedin (Dec 9, 2004). "All at sea over 'the Gulf'". Asia Times. Retrieved 2010-11-30.

- ↑ Eilts, Hermann (Fall 1980). "Security Considerations in the Persian Gulf". International Security. 5 (2): 79–113. doi:10.2307/2538446. JSTOR 2538446.

- ↑ Abedin, Mahan (December 4, 2004). "All at Sea over 'the Gulf'". Asia Times Online. Archived from the original on 2016-05-21.

- ↑ Bosworth, C. Edmund (1980). "The Nomenclature of the Persian Gulf". In Cottrell, Alvin J. The Persian Gulf States: A General Survey. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. xvii–xxxvi.

Not until the early 1960s does a major new development occur with the adoption by the Arab states bordering on the Gulf of the expression al-Khalij al-Arabi as weapon in the psychological war with Iran for political influence in the Gulf; but the story of these events belongs to a subsequent chapter on modern political and diplomatic history of the Gulf. (p. xxxiii.)

- ↑ "Iranian Archaeologists Uncover Paleolithic Stone Tools on Qeshm Island - Tasnim News Agency". Tasnim News Agency. Retrieved 2018-07-09.

- ↑ Rose, Jeffrey I. (December 2010). "New Light on Human Prehistory in the Arabo-Persian Gulf Oasis". Current Anthropology. 51 (6): 849–883. doi:10.1086/657397. Retrieved 2016-11-19.

- ↑ M. Th. Houtsma (1993). E.J. Brill's first encyclopaedia of Islam 1913–1936. ISBN 978-90-04-09796-4. Retrieved 2010-11-26.

- ↑ Pierre Briant (2006). From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire. Eisenbrauns. p. 761. ISBN 978-1-57506-120-7.

- ↑ British Institute of Persian Studies. "Siraf". Retrieved 2010-11-24.

- ↑ Juan R. I. Cole (1987). "Rival Empires of Trade and Imami Shiism in Eastern Arabia, 1300–1800". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 19 (2): 177–203 [186]. doi:10.1017/s0020743800031834. JSTOR 163353.

- ↑ http://english.irib.ir/news/political/item/60225-persian-gulf-national-day-in-foreign-ministry. Retrieved February 5, 2012. Missing or empty

|title=(help) ,IRIB, - ↑ Rahman 1979, pp. 138–139

- ↑ Rogan, Eugene; Murphey, Rhoads; Masalha, Nur; Durac, Vincent; Hinnebusch, Raymond (November 1999). "Review of The Ottoman Gulf: The Creation of Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and Qatar by Frederick F. Anscombe; The Blood-Red Arab Flag: An Investigation into Qasimi Piracy, 1797–1820 by Charles E. Davies; The Politics of Regional Trade in Iraq, Arabia and the Gulf, 1745–1900 by Hala Fattah". British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies. 26 (2): 339–342. doi:10.1080/13530199908705688. JSTOR 195948.

- ↑ "Shaikh Abdullah Bin Jassim Al Thani - Amiri Diwan". Amiri Diwan. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- ↑ Martin Blumenson; Robert W. Coakley; Stetson Conn; Byron Fairchild; Richard M. Leighton; Charles V.P. von Luttichau; Martin Blumenson; Robert W. Coakley; Stetson Conn; Byron Fairchild; Richard M. Leighton; Charles V.P. von Luttichau; Charles B. MacDonald; Sidney T. Mathews; Maurice Matloff; Ralph S. Mavrogordato; Leo J. Meyer; John Miller, Jr.; Louis Morton; Forrest C. Pogue; Roland G. Ruppenthal; Robert Ross Smith; Earl F. Ziemke. Command Decisions. Government Printing Office. p. 225.

- ↑ T. H. Vail Motter (1952). The Persian Corridor and aid to Russia, Volume 7, Part 1. Office of the Chief of Military History, Dept. of the Army.

- ↑ "Trucial states". LookLex Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2010-11-19.

- ↑ Donald Hawley (1970). Trucial States. p. 172. ISBN 978-0-04-953005-8. Retrieved 2010-11-19.

- ↑ Beaumont, Peter (December 23, 2006). "Blair was dangerously off target in his condemnation of Iran". The Guardian. London: Guardian Media Group. Archived from the original on 2016-07-30.

- ↑ "Classified document on Bahrain rankles Britain decades later". Reuters. 22 May 2015. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

The case shows how alive the history of British colonial rule still is in the Gulf today

- ↑ "UK-Bahrain sign landmark defence agreement". Foreign & Commonwealth Office. December 5, 2014. Retrieved 6 December 2014.

- ↑ "UK to establish £15m permanent Mid East military base". BBC. December 6, 2014.

- ↑ "East of Suez, West from Helmand: British Expeditionary Force and the next SDSR" (PDF). Oxford Research Group. December 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 July 2015. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- ↑ Marco Ramerini. "Portuguese in the Arabia and the Persian Gulf". Archived from the original on 2015-09-11. Retrieved 2010-11-27.

- ↑ Pernetta, John. (2004). Guide to the Oceans. Buffalo, NY: Firefly Books, Inc. p. 205. ISBN 978-1-55297-942-6.

- ↑ Morteza Aminmansour/Pars Times. "Pollution in Persian Gulf". Retrieved 2010-11-24.

- ↑ Dr. Gheilani A.M.H. Whales and Dolphins in Arabian Sea: Arabian Sea Survey (2007–2008). The Marine Science and Fisheries Center in the Ministry of Fisheries Wealth. Retrieved on December 17, 2014

- ↑ Jongbloed M. Whales and dolphins in the Gulf. Al Shindagha. Retrieved on December 17, 2014

- ↑ Jackson J. 2006. Diving with Giants. pp.59. New Holland Publishers Ltd. Retrieved on December 17, 2014

- ↑ Clapham P., Ivashchenko Y. Marine Fisheries Review. Retrieved on December 17, 2014

- ↑ Lambros M.. Whale Watching In Kuwait. LIVIN Q8. Retrieved on September 21, 2017

- ↑ Burahmah I.. 2013. Whale seen in kuwait seas. YouTube. Retrieved on September 21, 2017

- ↑ جرائم ومحاكم. 2015. حوت يسبح قرب أبراج الكويت. Youtube. Retrieved on September 21, 2017

- ↑ Khalaf N.. 2014. The 24-meters Blue Whale Skeleton at the Educational Science Museum in Kuwait City, State of Kuwait. issuu. Retrieved on September 21, 2017

- ↑ "PBS – The Voyage of the Odyssey – Track the Voyage – MALDIVES".

- 1 2 https://www.cbd.int/doc/meetings/mar/ebsaws-2015-02/other/ebsaws-2015-02-gobi-submission9-en.pdf

- ↑ 茂木陽一. "ホルムズ海峡でGTフィッシング②".

- ↑ Minton G.. 2017. Pre-print manuscript published on humpback whales in the Persian Gulf. Arabian Sea Whale Network. Retrieved on September 21, 2017

- ↑ Articles/meps. "pdf" (PDF). www.int-res.com.

- ↑ Sharif Ranjbar S., Dakhteh S.M., Waerebeek V.K. (2016). "Omura's whale (Balaenoptera omurai ) stranding on Qeshm Island, Iran: further evidence for a wide (sub)tropical distribution, including the Persian Gulf". bioRxiv 042614.

- ↑ Babu R. 2017. Whale tracing us in a boat at Kuwait sea area. Youtube. Retrieved on September 21, 2017

- ↑ Imisdocs/publications. "pdf" (PDF). www.vliz.be.

- ↑ Hoath R.. 2009. A Field Guide to the Mammals of Egypt. pp.112. The American University in Cairo Press. Retrieved on February 26. 2016

- ↑ Dr. Perrin F.W., Koch C.C. 2007. Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. pp.611. Academic Press. Retrieved on December 17, 2014

- ↑ "Yemen".

- ↑ WAM. 2017. Abu Dhabi has world’s largest population of humpback dolphins. Emirates 24/7. Retrieved on September 21, 2017

- ↑ Gulf News. 2017. Abu Dhabi proves a haven for humpback dolphins. Retrieved on September 21, 2017

- ↑ Sanker A.. 2017. Abu Dhabi leads world in humpback dolphin numbers. Khaleej Times. Retrieved on September 21, 2017

- 1 2 3 "Case Study". American.edu. Archived from the original on June 24, 2009. Retrieved 2009-07-10.

- ↑ "Persian Gulf Mermaids Face Environmental Threats". Maurice Picow. 2010-03-04. Retrieved 2010-11-19.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Jim Krane (July 3, 2006). "Development in Persian Gulf Threatens Wildlife". Discovery Channel. Archived from the original on 2006-09-23. Retrieved 2008-06-30.

- ↑ Tim Thomas & Ian Robinson (2001). "Turtles Rehabilitated After Persian Gulf Oil Spills". Retrieved 2010-11-23.

- ↑ Mandana Javidinejad (2007). "Dolphins of Persian Gulf are in danger". Payvand News Agency. Retrieved December 25, 2010.

- ↑ Vahid Sepehri (October 3, 2007). "Iran: Spill, Dolphin Deaths Spark Alarm At Persian Gulf Pollution". Radio Free Europe, Radio Liberty. Retrieved December 25, 2010.

- 1 2 Jen/fishbase.org (2003-06-30). "Fish Species in Persian Gulf". Retrieved 2010-11-24.

- 1 2 Debelius, H. (1993). Indian Ocean Tropical Fish Guide. Aquaprint Verlag GmbH. p. 5. ISBN 3-927991-01-5.

- 1 2 Emery K.O. (1956). "Sediments and water of the Persian Gulf". Bull AAPG. 401: 2354–2383. doi:10.1038/srep04250. PMC 3945051. PMID 24603901.

- 1 2 3 Pohl; Al-Muqdadi; Ali; Fawzi; Ehrlich; and Merkel (2014). "Discovery of a living coral reef in the coastal waters of Iraq". Sci. Rep. 4: 4250. doi:10.1038/srep04250. PMC 3945051. PMID 24603901.

- 1 2 "Dumping by Construction Crews Killing Bahrain Coral". Maurice Picow. 2010-06-16. Retrieved 2010-11-19.

- ↑ SunySB. "Mangals". Retrieved 2010-11-23.

- ↑ Yamada, Akiyo; Saitoh, Takeo; Mimura, Tetsuro; Ozeki, Yoshihiro (Fall 1980). "Expression of mangrove allene oxide cyclase enhances salt tolerance in Escherichia coli, yeast, and tobacco cells". Plant and Cell Physiology. 43 (8): 903–910. doi:10.1093/pcp/pcf108.

External links

| Look up persian gulf in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Persian Gulf. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Persian Gulf. |

- Qatar Digital Library – an online portal providing access to previously undigitised British Library archive materials relating to Gulf history and Arabic science

- Persian Gulf, Encyclopædia Iranica

- The Portuguese in the Arabian peninsula and in the Persian Gulf

- 32 historical map of Persian gulf, at flickr.com

- Persian Gulf from 1920

- Videos

[

.gif)

.jpg)