Great Plains

| Great Plains | |

| The Great Plains States | |

| Region | |

View of the Great Plains near Lincoln, Nebraska | |

| Country | |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 37°N 97°W / 37°N 97°WCoordinates: 37°N 97°W / 37°N 97°W |

| Length | 3,200 km (1,988 mi) |

| Width | 800 km (497 mi) |

| Area | 1,300,000 km2 (501,933 sq mi) |

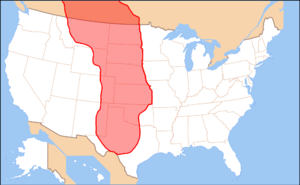

Approximate extent of the Great Plains[1] | |

The Great Plains (sometimes simply "the Plains") is the broad expanse of flat land (a plain), much of it covered in prairie, steppe, and grassland, that lies west of the Mississippi River tallgrass prairie in the United States and east of the Rocky Mountains in the U.S. and Canada. It embraces:

- The entirety of the U.S. states of Kansas, Nebraska, North Dakota, and South Dakota

- Parts of the states of Colorado, Iowa, Minnesota, Montana, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Texas, and Wyoming

- The southern portions of the Canadian provinces of Alberta, Manitoba, and Saskatchewan

The region is known for supporting extensive cattle ranching and dry farming.

The Canadian portion of the Plains is known as the Prairies. It covers much of Alberta and southern Saskatchewan, and a narrow band of southern Manitoba. Despite covering a relatively small geographic area, the Prairies are nevertheless home to the majority of each of the three provinces' respective populations.

Usage

The term "Great Plains" is used in the United States to describe a sub-section of the even more vast Interior Plains physiographic division, which covers much of the interior of North America. It also has currency as a region of human geography, referring to the Plains Indians or the Plains States.

In Canada the term is little used; Natural Resources Canada, the government department responsible for official mapping, treats the Interior Plains as one unit consisting of several related plateaux and plains. There is no region referred to as the "Great Plains" in The Atlas of Canada.[2] In terms of human geography, the term prairie is more commonly used in Canada, and the region is known as the Prairie Provinces or simply "the Prairies."

The North American Environmental Atlas, produced by the Commission for Environmental Cooperation, a NAFTA agency composed of the geographical agencies of the Mexican, American, and Canadian governments, uses the "Great Plains" as an ecoregion synonymous with predominant prairies and grasslands rather than as physiographic region defined by topography.[3] The Great Plains ecoregion includes five sub-regions: Temperate Prairies, West-Central Semi-Arid Prairies, South-Central Semi-Arid Prairies, Texas Louisiana Coastal Plains, and Tamaulipas-Texas Semi-Arid Plain, which overlap or expand upon other Great Plains designations.[4]

Extent

The region is about 500 mi (800 km) east to west and 2,000 mi (3,200 km) north to south. Much of the region was home to American bison herds until they were hunted to near extinction during the mid/late-19th century. It has an area of approximately 500,000 sq mi (1,300,000 km2). Current thinking regarding the geographic boundaries of the Great Plains is shown by this map at the Center for Great Plains Studies, University of Nebraska–Lincoln.[1]

The term "Great Plains", for the region west of about the 96th and east of the Rocky Mountains, was not generally used before the early 20th century. Nevin Fenneman's 1916 study Physiographic Subdivision of the United States[5] brought the term Great Plains into more widespread usage. Before that the region was almost invariably called the High Plains, in contrast to the lower Prairie Plains of the Midwestern states.[6] Today the term "High Plains" is used for a subregion of the Great Plains.

Geography

The Great Plains are the westernmost portion of the vast North American Interior Plains, which extend east to the Appalachian Plateau. The United States Geological Survey divides the Great Plains in the United States into ten physiographic subdivisions:

- Coteau du Missouri or Missouri Plateau (which also extends into Canada), glaciated – east central South Dakota, northern and eastern North Dakota and northeastern Montana;

- Coteau du Missouri, unglaciated – western South Dakota, northeastern Wyoming, southwestern North Dakota and southeastern Montana;

- Black Hills – western South Dakota;

- High Plains – southeastern Wyoming, southwestern South Dakota, western Nebraska (including the Sand Hills), eastern Colorado, western Kansas, western Oklahoma, eastern New Mexico, and northwestern Texas (including the Llano Estacado and Texas Panhandle);

- Plains Border – central Kansas and northern Oklahoma (including the Flint, Red and Smoky Hills);

- Colorado Piedmont – eastern Colorado;

- Raton section – northeastern New Mexico;

- Pecos Valley – eastern New Mexico;

- Edwards Plateau – south central Texas; and

- Central Texas section – central Texas.

The Great Plains consist of a broad stretch of country underlain by nearly horizontal strata extends westward from the 97th meridian west to the base of the Rocky Mountains, a distance of from 300 to 500 miles (480 to 800 km). It extends northward from the Mexican boundary far into Canada. Although the altitude of the plains increases gradually from 600 or 1,200 ft (370 m) on the east to 4,000–5,000 or 6,000 feet (1,800 m) near the mountains, the local relief is generally small. The semi-arid climate excludes tree growth and opens far-reaching views.[7]

The plains are by no means a simple unit. They are of diverse structure and of various stages of erosional development. They are occasionally interrupted by buttes and escarpments. They are frequently broken by valleys. Yet on the whole, a broadly extended surface of moderate relief so often prevails that the name, Great Plains, for the region as a whole is well-deserved.[7]

The western boundary of the plains is usually well-defined by the abrupt ascent of the mountains. The eastern boundary of the plains is more climatic than topographic. The line of 20 in. of annual rainfall trends a little east of northward near the 97th meridian. If a boundary must be drawn where nature presents only a gradual transition, this rainfall line may be taken to divide the drier plains from the moister prairies. The plains may be described in northern, intermediate, central and southern sections, in relation to certain peculiar features.[7]

Northern Great Plains

The northern section of the Great Plains, north of latitude 44°, including eastern Montana, north-eastern Wyoming, most of North and South Dakota, and the Canadian Prairies, is a moderately dissected peneplain.

This is one of the best examples of its kind. The strata here are Cretaceous or early Tertiary, lying nearly horizontal. The surface is shown to be a plain of degradation by a gradual ascent here and there to the crest of a ragged escarpment, the escarpment-remnant of a resistant stratum. There are also the occasional lava-capped mesas and dike formed ridges, surmounting the general level by 500 ft (150 m) or more and manifestly demonstrating the widespread erosion of the surrounding plains. All these reliefs are more plentiful towards the mountains in central Montana. The peneplain is no longer in the cycle of erosion that witnessed its production. It appears to have suffered a regional uplift or increase in elevation, for the upper Missouri River and its branches no longer flow on the surface of the plain, but in well graded, maturely opened valleys, several hundred feet below the general level. A significant exception to the rule of mature valleys occurs, however, in the case of the Missouri, the largest river, which is broken by several falls on hard sandstones about 50 miles (80 km) east of the mountains. This peculiar feature is explained as the result of displacement of the river from a better graded preglacial valley by the Pleistocene ice sheet. Here, the ice sheet overspread the plains from the moderately elevated Canadian highlands far on the north-east, instead of from the much higher mountains near by on the west. The present altitude of the plains near the mountain base is 4,000 ft (1,200 m).[7]

The northern plains are interrupted by several small mountain areas. The Black Hills, chiefly in western South Dakota, are the largest group. They rise like a large island from the sea, occupying an oval area of about 100 miles (160 km) north-south by 50 miles (80 km) east-west. At Black Elk Peak, they reach an altitude of 7,216 feet (2,199 m) and have an effective relief over the plains of 2000 or 3,000 ft (910 m) This mountain mass is of flat-arched, dome-like structure, now well dissected by radiating consequent streams. The weaker uppermost strata have been eroded down to the level of the plains where their upturned edges are evenly truncated. The next following harder strata have been sufficiently eroded to disclose the core of underlying igneous and metamorphic crystalline rocks in about half of the domed area.[7]

Intermediate Great Plains

In the intermediate section of the plains, between latitudes 44° and 42°, including southern South Dakota and northern Nebraska, the erosion of certain large districts is peculiarly elaborate. Known as the Badlands, it is a minutely dissected form with a relief of a few hundred feet. This is due to several causes:

- the dry climate, which prevents the growth of a grassy turf

- the fine texture of the Tertiary strata in the badland districts

- every little rill, at times of rain, carves its own little valley.[7]

Central Great Plains

The central section of the Great Plains, between latitudes 42° and 36°, occupying eastern Colorado and western Kansas, is, briefly stated, for the most part a dissected fluviatile plain. That is, this section was once smoothly covered with a gently sloping plain of gravel and sand that had been spread far forward on a broad denuded area as a piedmont deposit by the rivers which issued from the mountains. Since then, it has been more or less dissected by the erosion of valleys. The central section of the plains thus presents a marked contrast to the northern section. While the northern section owes its smoothness to the removal of local gravels and sands from a formerly uneven surface by the action of degrading rivers and their inflowing tributaries, the southern section owes its smoothness to the deposition of imported gravels and sands upon a previously uneven surface by the action of aggrading rivers and their outgoing distributaries. The two sections are also alike in that residual eminences still here and there surmount the peneplain of the northern section, while the fluviatile plain of the central section completely buried the pre-existent relief. Exception to this statement must be made in the southwest, close to the mountains in southern Colorado, where some lava-capped mesas (Mesa de Maya, Raton Mesa) stand several thousand feet above the general plain level, and thus testify to the widespread erosion of this region before it was aggraded.[7]

Southern Great Plains

The southern section of the Great Plains, between latitudes 35.5° and 25.5° lies in western Texas and eastern New Mexico. Like the central section, it is for the most part a dissected fluviatile plain. However, the lower lands which surround it on all sides place it in so strong relief that it stands up as a table-land, known from the time of Mexican occupation as the Llano Estacado. It measures roughly 150 miles (240 km) east-west and 400 miles (640 km) north-south. It is of very irregular outline, narrowing to the south. Its altitude is 5,500 feet (1,700 m) at the highest western point, nearest the mountains whence its gravels were supplied. From there, it slopes southeastward at a decreasing rate, first about 12 ft., then about 7 ft per mile (1.3 m/km), to its eastern and southern borders, where it is 2,000 feet (610 m) in altitude. Like the High Plains farther north, it is extraordinarily smooth.[7]

It is very dry, except for occasional shallow and temporary water sheets after rains. The Llano is separated from the plains on the north by the mature consequent valley of the Canadian River, and from the mountains on the west by the broad and probably mature valley of the Pecos River. On the east, it is strongly undercut by the retrogressive erosion of the headwaters of the Red, Brazos and Colorado rivers of Texas and presents a ragged escarpment approximately 500 to 800 ft (240 m) high, overlooking the central denuded area of that state. There, between the Brazos and Colorado rivers, occurs a series of isolated outliers capped by a limestone which underlies both the Llano Uplift on the west and the Grand Prairies escarpment on the east. The southern and narrow part of the table-land, called the Edwards Plateau, is more dissected than the rest, and falls off to the south in a frayed-out fault scarp. This scarp overlooks the coastal plain of the Rio Grande embayment. The central denuded area, east of the Llano, resembles the east-central section of the plains in exposing older rocks. Between these two similar areas, in the space limited by the Canadian and Red Rivers, rise the subdued forms of the Wichita Mountains in Oklahoma, the westernmost member of the Ouachita system.[7]

Paleontology

During the Cretaceous Period (145–66 million years ago), the Great Plains were covered by a shallow inland sea called the Western Interior Seaway. However, during the Late Cretaceous to the Paleocene (65–55 million years ago), the seaway had begun to recede, leaving behind thick marine deposits and a relatively flat terrain which the seaway had once occupied.

During the Cenozoic era, specifically about 25 million years ago during the Miocene and Pliocene epochs, the continental climate became favorable to the evolution of grasslands. Existing forest biomes declined and grasslands became much more widespread. The grasslands provided a new niche for mammals, including many ungulates and glires, that switched from browsing diets to grazing diets. Traditionally, the spread of grasslands and the development of grazers have been strongly linked. However, an examination of mammalian teeth suggests that it is the open, gritty habitat and not the grass itself which is linked to diet changes in mammals, giving rise to the "grit, not grass" hypothesis.[8]

Paleontological finds in the area have yielded bones of mammoths, saber-toothed cats and other ancient animals,[9] as well as dozens of other megafauna (large animals over 100 lb [45 kg]) – such as giant sloths, horses, mastodons, and American lion – that dominated the area of the ancient Great Plains for thousands to millions of years. The vast majority of these animals became extinct in North America at the end of the Pleistocene (around 13,000 years ago).[10]

Climate

In general, the Great Plains have a wide variety of weather through the year, with very cold and harsh winters and very hot and humid summers. Wind speeds are often very high, especially in winter. Grasslands are among the least protected biomes.[11] Humans have converted much of the prairies for agricultural purposes or to create pastures. The Great Plains have dust storms mostly every year or so.

The 100th meridian roughly corresponds with the line that divides the Great Plains into an area that receive 20 in (510 mm) or more of rainfall per year and an area that receives less than 20 in (510 mm). In this context, the High Plains, as well as Southern Alberta, south-western Saskatchewan and Eastern Montana are mainly semi arid steppe land and are generally characterised by rangeland or marginal farmland. The region (especially the High Plains) is periodically subjected to extended periods of drought; high winds in the region may then generate devastating dust storms. The eastern Great Plains near the eastern boundary falls in the humid subtropical climate zone in the southern areas, and the northern and central areas fall in the humid continental climate.

Many thunderstorms occur in the plains in the spring through summer. The southeastern portion of the Great Plains is the most tornado active area in the world and is sometimes referred to as Tornado Alley.

Flora

The Great Plains are part of the floristic North American Prairies Province, which extends from the Rocky Mountains to the Appalachians.

History

Original American contact

The first Americans (Paleo-Indians) who arrived to the Great Plains were successive indigenous cultures who are known to have inhabited the Great Plains for thousands of years, over 15,000 years ago.[12][13] Humans entered the North American continent in waves of migration, mostly over Beringia, the Bering Straits land bridge.

Historically the Great Plains were the range of the bison and of the culture of the Plains Indians, whose tribes included the Blackfoot, Crow, Sioux, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Comanche, and others. Eastern portions of the Great Plains were inhabited by tribes who lived in semi-permanent villages of earth lodges, such as the Arikara, Mandan, Pawnee and Wichita.

European contact

With the arrival of Francisco Vázquez de Coronado, a Spanish conquistador, the first recorded history of encounter between Europeans and Native Americans in the Great Plains occurred in Texas, Kansas and Nebraska from 1540 to 1542. In that same time period, Hernando de Soto crossed a west-northwest direction in what is now Oklahoma and Texas. Today this is known as the De Soto Trail. The Spanish thought the Great Plains were the location of the mythological Quivira and Cíbola, a place said to be rich in gold.

Over the next one hundred years, founding of the fur trade brought thousands of ethnic Europeans into the Great Plains. Fur trappers from France, Spain, Britain, Russia and the young United States made their way across much of the region, making regular contacts with Native Americans. After the United States acquired the Louisiana Purchase in 1803 and conducted the Lewis and Clark Expedition in 1804–1806, more information about the Plains became available and various pioneers entered the areas.

Manuel Lisa, based in St. Louis, established a major fur trading site at his Fort Lisa on the Missouri River in Nebraska. Fur trading posts were often the basis of later settlements. Through the 19th century, more European Americans and Europeans migrated to the Great Plains as part of a vast westward expansion of population. New settlements became dotted across the Great Plains.

The new immigrants also brought diseases against which the Native Americans had no resistance. Between a half and two-thirds of the Plains Indians are thought to have died of smallpox by the time of the 1803 Louisiana Purchase.[15]

Early European settlements on the Great Plains

French

British

American

- Fort Lisa (1809), North Dakota

- Fort Lisa (1812), Nebraska

- Fontenelle's Post (1822), Nebraska

- Cabanne's Trading Post (1822), Nebraska

Pioneer settlement

After 1870, the new railroads across the Plains brought hunters who killed off almost all the bison for their hides. The railroads offered attractive packages of land and transportation to European farmers, who rushed to settle the land. They (and Americans as well) also took advantage of the homestead laws to obtain free farms. Land speculators and local boosters identified many potential towns, and those reached by the railroad had a chance, while the others became ghost towns. In Kansas, for example, nearly 5000 towns were mapped out, but by 1970 only 617 were actually operating. In the mid-20th century, closeness to an interstate exchange determined whether a town would flourish or struggle for business.[16]

Much of the Great Plains became open range, or rangeland where cattle roamed free, hosting ranching operations where anyone was theoretically free to run cattle. In the spring and fall, ranchers held roundups where their cowboys branded new calves, treated animals and sorted the cattle for sale. Such ranching began in Texas and gradually moved northward. Between 1866 and 1895, cowboys herded 10 million cattle north to rail heads such as Dodge City, Kansas[17] and Ogallala, Nebraska; from there, cattle were shipped eastward.[18]

Many foreign investors, especially British, financed the great ranches of the era. Overstocking of the range and the terrible winter of 1886 resulted in a disaster, with many cattle starved and frozen to death. Theodore Roosevelt, a rancher in the Dakotas, lost his entire investment; he returned east to reenter politics. From then on, ranchers generally raised feed to ensure they could keep their cattle alive over winter.

To allow for agricultural development of the Great Plains and house a growing population, the US passed the Homestead Acts of 1862: it allowed a settler to claim up to 160 acres (65 ha) of land, provided that he lived on it for a period of five years and cultivated it. The provisions were expanded under the Kinkaid Act of 1904 to include a homestead of an entire section. Hundreds of thousands of people claimed such homesteads, sometimes building sod houses out of the very turf of their land. Many of them were not skilled dryland farmers and failures were frequent. Much of the Plains were settled during relatively wet years. Government experts did not understand how farmers should cultivate the prairies and gave advice counter to what would have worked. Germans from Russia who had previously farmed, under similar circumstances, in what is now Ukraine were marginally more successful than other homesteaders. The Dominion Lands Act of 1871 served a similar function for establishing homesteads on the prairies in Canada.[19]

Social life

The railroads opened up the Great Plains for settlement, for now it was possible to ship wheat and other crops at low cost to the urban markets in the East, and Europe. Homestead land was free for American settlers. Railroads sold their land at cheap rates to immigrants in expectation they would generate traffic as soon as farms were established. Immigrants poured in, especially from Germany and Scandinavia. On the plains, very few single men attempted to operate a farm or ranch by themselves; they clearly understood the need for a hard-working wife, and numerous children, to handle the many chores, including child-rearing, feeding and clothing the family, managing the housework, feeding the hired hands, and, especially after the 1930s, handling paperwork and financial details.[20] During the early years of settlement, farm women played an integral role in assuring family survival by working outdoors. After approximately one generation, women increasingly left the fields, thus redefining their roles within the family. New technology including sewing and washing machines encouraged women to turn to domestic roles. The scientific housekeeping movement, promoted across the land by the media and government extension agents, as well as county fairs which featured achievements in home cookery and canning, advice columns for women regarding farm bookkeeping, and home economics courses in the schools.[21]

Although the eastern image of farm life in the prairies emphasized the isolation of the lonely farmer and wife, plains residents created busy social lives for themselves. They often sponsored activities that combined work, food and entertainment such as barn raisings, corn huskings, quilting bees,[22] Grange meetings, church activities and school functions. Women organized shared meals and potluck events, as well as extended visits between families.[23] The Grange was a nationwide farmers' organization, they reserved high offices for women, and gave them a voice in public affairs.[24]

After 19th century

The region roughly centered on the Oklahoma Panhandle, including southeastern Colorado, southwestern Kansas, the Texas Panhandle, and extreme northeastern New Mexico was known as the Dust Bowl during the late 1920s and early 1930s. The effect of an extended drought, inappropriate cultivation, and financial crises of the Great Depression, forced many farmers off the land throughout the Great Plains.

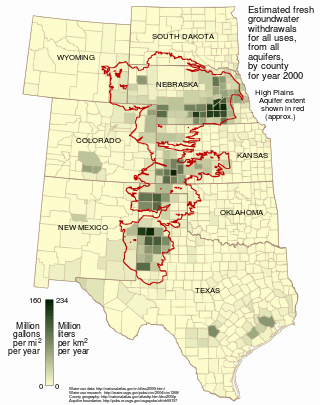

From the 1950s on, many areas of the Great Plains have become productive crop-growing areas because of extensive irrigation on large landholdings. The United States is a major exporter of agricultural products. The southern portion of the Great Plains lies over the Ogallala Aquifer, a huge underground layer of water-bearing strata dating from the last ice age. Center pivot irrigation is used extensively in drier sections of the Great Plains, resulting in aquifer depletion at a rate that is greater than the ground's ability to recharge.[25]

Population decline

The rural Plains have lost a third of their population since 1920. Several hundred thousand square miles of the Great Plains have fewer than 6 inhabitants per square mile (2.3 inhabitants per square kilometer)—the density standard Frederick Jackson Turner used to declare the American frontier "closed" in 1893. Many have fewer than 2 inhabitants per square mile (0.77 inhabitants per square kilometer). There are more than 6,000 ghost towns in the state of Kansas alone, according to Kansas historian Daniel Fitzgerald. This problem is often exacerbated by the consolidation of farms and the difficulty of attracting modern industry to the region. In addition, the smaller school-age population has forced the consolidation of school districts and the closure of high schools in some communities. The continuing population loss has led some to suggest that the current use of the drier parts of the Great Plains is not sustainable,[26] and there has been a proposal – the "Buffalo Commons" – to return approximately 139,000 sq mi (360,000 km2) of these drier parts to native prairie land.

Wind power

The Great Plains contribute substantially to wind power in the United States. In July 2008, T. Boone Pickens, who developed wind farms after a long career as a petroleum executive, called for the U.S. to invest $1 trillion to build an additional 200,000 MW of wind power nameplate capacity in the Plains, as part of his Pickens Plan. Pickens cited Sweetwater, Texas as an example of economic revitalization driven by wind power development.[27][28][29]

Sweetwater was a struggling town typical of the Plains, steadily losing businesses and population, until wind turbines came to surrounding Nolan County.[30] Wind power brought jobs to local residents, along with royalty payments to landowners who leased sites for turbines, reversing the town's population decline. Pickens claims the same economic benefits are possible throughout the Plains, which he refers to as North America's "wind corridor."

See also

- 1837 Great Plains smallpox epidemic

- Bison hunting

- Llano Estacado

- Great American Desert

- Great bison belt

- Great Plains Art Museum

- Great Plains Conservation Program

- Northern Great Plains History Conference

- Territories of the United States on stamps

- Dust Bowl

International steppe-lands

- Eurasian Steppe

- Kazakh Steppe

- Pampas, in Argentina, Uruguay, Brazil

- Pontic-Caspian steppe

- Puszta

References

- 1 2 Wishart, David. 2004. The Great Plains Region, In: Encyclopedia of the Great Plains, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, pp. xiii-xviii. ISBN 0-8032-4787-7

- ↑ Atlas.nrcan.gc.ca Archived 2013-01-22 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ CEC.org

- ↑ "About the National Health and Environmental Effects Research Laboratory (NHEERL)".

- ↑ Fenneman, Nevin M. (January 1917). "Physiographic Subdivision of the United States". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 3 (1): 17–22. doi:10.1073/pnas.3.1.17. OCLC 43473694. PMC 1091163. PMID 16586678.

- ↑ Brown, Ralph Hall (1948). Historical Geography of the United States. New York: Harcourt, Brace & Co. pp. 373–374. OCLC 186331193.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

- ↑ Phillip E. Jardine, Christine M. Janis, Sarda Sahney, Michael J. Benton. "Grit not grass: Concordant patterns of early origin of hypsodonty in Great Plains ungulates and Glires." Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. December 2012:365–366, 1–10

- ↑ "Ice Age Animals". Illinois State Museum.

- ↑ "A Plan For Reintroducing Megafauna To North America". ScienceDaily. October 2, 2006.

- ↑ Threats Assessment for the Northern Great Plains Ecoregion

- ↑ "First Americans arrived 2500 years before we thought – life – 24 March 2011". New Scientist. Retrieved 2014-02-12.

- ↑ Hanna, Bill (2010-08-28). "Texas artifacts 'strongest evidence yet' that humans arrived in North America earlier than thought". Star-telegram.com. Retrieved 2014-02-12.

- ↑ Rees, Amanda (2004). The Great Plains region. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 18. ISBN 0-313-32733-5. Retrieved 2009-09-04.

- ↑ "Emerging Infections: Microbial Threats to Health in the United States (1992)". Institute of Medicine (IOM).

- ↑ Raymond A. Mohl, The New City: Urban America in the Industrial Age, 1860–1920 (1985) p. 69

- ↑ Robert R. Dykstra, Cattle Towns: A Social History of the Kansas Cattle Trading Centers (1968)

- ↑ John Rossel, "The Chisholm Trail," Kansas Historical Quarterly (1936) Vol. 5, No. 1 pp 3–14 online edition

- ↑ Ian Frazier, Great Plains (2001) p. 72

- ↑ Deborah Fink, Agrarian Women: Wives and Mothers in Rural Nebraska, 1880–1940 (1992).

- ↑ Chad Montrie, "'Men Alone Cannot Settle a Country:' Domesticating Nature in the Kansas-Nebraska Grasslands", Great Plains Quarterly, Fall 2005, Vol. 25 Issue 4, pp. 245–258. Online

- ↑ Karl Ronning, "Quilting in Webster County, Nebraska, 1880–1920", Uncoverings, 1992, Vol. 13, pp. 169–191.

- ↑ Nathan B. Sanderson, "More Than a Potluck", Nebraska History, Fall 2008, Vol. 89 Issue 3, pp. 120–131.

- ↑ Donald B. Marti, Women of the Grange: Mutuality and Sisterhood in Rural America, 1866–1920 (1991)

- ↑ Bobby A. Stewart and Terry A. Howell, Encyclopedia of water science (2003) p. 43

- ↑ Amanda Rees, The Great Plains region (2004) p. xvi

- ↑ "Legendary Texas oilman embraces wind power". Star Tribune. 2008-07-25. Archived from the original on 2008-07-27. Retrieved 2008-08-24.

- ↑ Fahey, Anna (2008-07-09). "Texas Oil Man Says We Can Break the Addiction". Sightline Daily. Retrieved 2008-08-24.

- ↑ "T. Boone Pickens Places $2 Billion Order for GE Wind Turbines". Wind Today Magazine. 2008-05-16. Archived from the original on 2008-10-01. Retrieved 2008-08-24.

- ↑ Block, Ben (2008-07-24). "In Windy West Texas, An Economic Boom". Archived from the original on 2009-01-09. Retrieved 2008-11-05.

Further reading

- Bonnifield, Paul. The Dust Bowl: Men, Dirt, and Depression, University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, New Mexico, 1978, hardcover, ISBN 0-8263-0485-0.

- Courtwright, Julie. Prairie Fire: A Great Plains History (University Press of Kansas, 2011) 274 pp.

- Danbom, David B. Sod Busting: How families made farms on the 19th-century Plains (2014)

- Eagan, Timothy. The Worst Hard Time : the Untold Story of Those Who Survived the Great American Dust Bowl. Boston : Houghton Mifflin Co., 2006.

- Forsberg, Michael, Great Plains: America's Lingering Wild, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, Illinois, 2009, ISBN 978-0-226-25725-9

- Gilfillan, Merrill. Chokecherry Places, Essays from the High Plains, Johnson Press, Boulder, Colorado, trade paperback, ISBN 1-55566-227-7.

- Grant, Michael Johnston. Down and Out on the Family Farm: Rural Rehabilitation in the Great Plains, 1929–1945, University of Nebraska Press, 2002, ISBN 0-8032-7105-0

- Hurt, R. Douglas. The Big Empty: The Great Plains in the Twentieth Century (University of Arizona Press; 2011) 315 pages; the environmental, social, economic, and political history of the region.

- Hurt, R. Douglas. The Great Plains during World War II. University of Nebraska Press. 2008. Pp. xiii, 507.

- Mills, David W. Cold War in a Cold Land: Fighting Communism on the Northern Plains (2015) Col War era; excerpt

- Peirce, Neal R. The Great Plains States of America: People, Politics, and Power in the Nine Great Plains States (1973)

- Raban, Jonathan. Bad Land: An American Romance. Vintage Departures, division of Vintage Books, New York, 1996. Winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award for Nonfiction.

- Rees, Amanda. The Great Plains Region: The Greenwood Encyclopedia of American Regional Cultures (2004)

- Stegner, Wallace. Wolf Willow, A history, a story, and a memory of the last plains frontier, Viking Compass Book, New York, 1966, trade paperback, ISBN 0-670-00197-X

- Wishart, David J. ed. Encyclopedia of the Great Plains, University of Nebraska Press, 2004, ISBN 0-8032-4787-7. complete text online

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Great Plains. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Great Plains. |

- Kansas Heritage Group: Native Prairie, Preserve, Flowers, and Research

- Library of Congress: Great Plains

- University of Nebraska-Lincoln: Center for Great Plains Studies

- Photos of the Southern Great Plains including the Llano Estacado, West Texas, and Eastern New Mexico

- Oklahoma Digital Maps: Digital Collections of Oklahoma and Indian Territory