Chechen language

| Chechen | |

|---|---|

| нохчийн мотт / noxçiyn mott / نَاخچیین موٓتت / ნოხჩიი მუოთთ | |

| Native to | Russia |

| Region | Chechnya |

| Ethnicity | Chechens |

Native speakers | 1.4 million (2010)[1] |

|

Cyrillic, Latin (present) Arabic, Georgian (historical) | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 |

ce |

| ISO 639-2 |

che |

| ISO 639-3 |

che |

| Glottolog |

chec1245[2] |

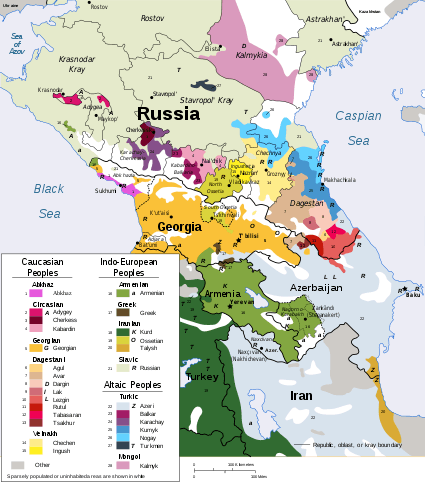

Chechen (нохчийн мотт / noxçiyn mott / نَاخچیین موٓتت / ნოხჩიი მუოთთ, [ˈnɔx.t͡ʃiːn mu͜ɔt]) is a Northeast Caucasian language spoken by more than 1.4 million people, mostly in the Chechen Republic and by members of the Chechen diaspora throughout Russia, Jordan, Central Asia (mainly Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan), and Georgia.

Classification

Chechen is a Northeast Caucasian language. Together with the closely related Ingush, with which there exists a large degree of mutual intelligibility and shared vocabulary, it forms the Vainakh branch.

Dialects

There are a number of Chechen dialects: Akkish, Chantish, Chebarloish, Malkhish, Nokhchmakhkakhoish, Orstkhoish, Sharoish, Shuotoish, Terloish, Itum-Qalish, and Himoish. The Kisti dialect of Georgia is not easily understood by northern Chechens without a few days' practice. One difference in pronunciation is that Kisti aspirated consonants remain aspirated when doubled (fortis) or after /s/, whereas they lose their aspiration in other dialects in these situations.

Dialects of Chechen can be classified by their geographic position within the Chechen Republic. The dialects of the northern lowlands are often referred to as "Oharoy muott" (literally "lowlander's language") and the dialect of the southern mountain tribes is known as "Laamaroy muott" (lit. "mountainer's language"). Oharoy muott forms the basis for much of the standard and literary Chechen language, which can largely be traced to the regional dialects of Urus-Martan and contemporary Grozny. Laamaroy dialects include (but are not limited to) Chebarloish, Sharoish, Itum-Qalish, Kisti, and Himoish. Until recently, however, Himoy was undocumented and was considered a branch of Sharoish, as many dialects are also used as the basis of intertribal (teip) communication within a larger Chechen "tukkhum". Laamaroy dialects such as Sharoish, Himoish and Chebarloish are more conservative and retain many features from Proto–Chechen. For instance, many of these dialects lack a number of vowels found in the standard language which were a result of long-distance assimilation between vowel sounds. Additionally, the Himoy dialect preserves word-final, post-tonic vowels as a schwa [ə], indicating Laamaroy and Ohwaroy dialects were already separate at the time that Oharoy dialects were undergoing assimilation.

Geographic distribution

According to the Russian Census of 2010, 1,350,000 people reported being able to speak Chechen.[1]

Official status

Jordan

Chechens in Jordan have good relations with the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan and are able to practice their own culture and language. Chechen language usage is strong among the Chechen community in Jordan. Chechens are bilingual in both Chechen and Arabic, but do not speak Arabic among themselves, only speaking Chechen to other Chechens. Some Jordanians are literate in Chechen as well, having managed to read and write to people visiting Jordan from Chechnya.[4]

Phonology

Some phonological characteristics of Chechen include its wealth of consonants and sounds similar to Arabic and the Salishan languages of North America, as well as a large vowel system resembling those of Swedish and German.

Consonants

The Chechen language has, like most indigenous languages of the Caucasus, a large number of consonants: about 40 to 60 (depending on the dialect and the analysis), far more than in most European languages. Typical of the region, a four-way distinction between voiced, voiceless, ejective, and geminate fortis stops is found.[5]

| Labial | Alveolar | Postalveolar | Velar | Uvular | Epiglottal | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | |||||

| Plosive | pʰ b pʼ pː |

tʰ d tʼ tː |

kʰ ɡ kʼ kː |

qʰ qʼ qː |

ʡ | ʔ | |

| Affricate | tsʰ dz tsʼ tsː |

tʃʰ dʒ tʃʼ |

|||||

| Fricative | v | s z | ʃ ʒ | x ʁ | ʜ | h | |

| Rhotic | r r̥ | ||||||

| Approximant | w | l | j | ||||

Nearly any consonant may be fortis because of focus gemination, but only the ones above are found in roots. The consonants of the t cell and /l/ are denti-alveolar; the others of that column are alveolar. /x/ is a back velar, but not quite uvular. The lateral /l/ may be velarized, unless it's followed by a front vowel. The trill /r/ is usually articulated with a single contact, and therefore sometimes described as a tap [ɾ]. Except in the literary register, and even then only for some speakers, the voiced affricates /dz/, /dʒ/ have merged into the fricatives /z/, /ʒ/. A voiceless labial fricative /f/ is found only in European loanwords. /w/ appears both in diphthongs and as a consonant; as a consonant, it has an allophone [v] before front vowels.

The approximately twenty pharyngealized consonants do not appear in the table above. Labial, alveolar, and postalveolar consonants may be pharyngealized, except for ejectives. Pharyngealized consonants do not occur in verbs or adjectives, and in nouns and adverbs they occur predominantly before the low vowels /a, aː/ ([ə, ɑː]).

Except when following a consonant, /ʢ/ is phonetically [ʔˤ], and can be argued to be a glottal stop before a "pharyngealized" (actually epiglottalized) vowel. However, it does not have the distribution constraints characteristic of the anterior pharyngealized (epiglottalized) consonants. Although these may be analyzed as an anterior consonant plus /ʢ/ (they surface for example as [dʢ] when voiced and [pʰʜ] when voiceless), Nichols argues that given the severe constraints against consonant clusters in Chechen, it is more useful to analyze them as single consonants.

The voiceless alveolar trill /r̥/ contrasts with the voiced version /r/, but only occurs in two roots, vworh "seven" and barh "eight".

Vowels

Unlike most other languages of the Caucasus, Chechen has an extensive inventory of vowel sounds, about 44, putting its range higher than most languages of Europe (most vowels being the product of environmentally-conditioned allophonic variation, which varies by both dialect and method of analysis). Many of the vowels are due to umlaut, which is highly productive in the standard dialect. None of the spelling systems used so far have distinguished the vowels with complete accuracy.

| front unrounded |

front rounded |

back~ central |

|---|---|---|

| ɪ iː | y yː | ʊ uː |

| je ie | ɥø yø | wo uo |

| e̞ e̞ː | ø øː | o̞ o̞ː |

| æ æː | ə ɑː |

All vowels may be nasalized. Nasalization is imposed by the genitive, infinitive, and for some speakers the nominative case of adjectives. Nasalization is not strong, but it is audible even in final vowels, which are devoiced.

Some of the diphthongs have significant allophony: /ɥø/ = [ɥø], [ɥe], [we]; /yø/ = [yø], [ye]; /uo/ = [woː], [uə].

In closed syllables, long vowels become short in most dialects (not Kisti), but are often still distinct from short vowels (shortened [i], [u], [ɔ], and [ɑ̤] vs. short [ɪ], [ʊ], [o], and [ə], for example), though which remain distinct depends on the dialect. /æ/, /æː/ and /e/, /eː/ are in complementary distribution (/æ/ occurs after pharyngealized consonants, whereas /e/ does not, and /æː/—identical with /æ/ for most speakers—occurs in closed syllables, while /eː/ does not) but speakers strongly feel that they are distinct sounds.

Pharyngealization appears to be a feature of the consonants, though some analyses treat it as a feature of the vowels. However, Nichols argues that this does not capture the situation in Chechen well, whereas it is more clearly a feature of the vowel in Ingush: Chechen [tsʜaʔ] "one", Ingush [tsaʔˤ], which she analyzes as /tsˤaʔ/ and /tsaˤʔ/. Vowels have a delayed murmured onset after pharyngealized voiced consonants and a noisy aspirated onset after pharyngealized voiceless consonants. The high vowels /i/, /y/, /u/ are diphthongized, [əi], [əy], [əu], whereas the diphthongs /je/, /wo/ undergo metathesis, [ej], [ow].

Phonotactics

Chechen permits syllable-initial clusters /st px tx/, and non-initial /x r l/ plus any consonant and any obstruent plus a uvular of the same manner. The only cluster of three consonants permitted is /rst/.[6]

Grammar

Chechen is an agglutinative language with an ergative–absolutive morphosyntactic alignment. Chechen nouns belong to one of several genders or classes (6), each with a specific prefix with which the verb or an accompanying adjective agrees. The verb does not agree with the subject or object's person or number, having only tense forms and participles. Among these are an optative and an antipassive. Some verbs, however, do not take these prefixes.[7]

Chechen is an ergative, dependent-marking language using eight cases (absolutive, genitive, dative, ergative, allative, instrumental, locative and comparative) and a large number of postpositions to indicate the role of nouns in sentences.

Word order is consistently left-branching (like in Japanese or Turkish), so that adjectives, demonstratives and relative clauses precede the nouns they modify. Complementizers and adverbial subordinators, as in other Northeast and in Northwest Caucasian languages, are affixes rather than independent words.

Chechen also presents interesting challenges for lexicography, as creating new words in the language relies on fixation of whole phrases rather than adding to the end of existing words or combining existing words. It can be difficult to decide which phrases belong in the dictionary, because the language's grammar does not permit the borrowing of new verbal morphemes to express new concepts.[8] Instead, the verb dan (to do) is combined with nominal phrases to correspond with new concepts imported from other languages.

Noun classes

Chechen nouns are divided into six lexically arbitrary noun classes[9]. Morphologically, noun classes may be indexed by changes in the prefix of the accompanying verb and, in many cases, the adjective too. The first two of these classes apply to human beings, although some grammarians count these as two and some as a single class; the other classes however are much more lexically arbitrary. Chechen noun classes are named according to the prefix that indexes them:

| Noun class | Noun example | Singular prefix | Plural prefix | Singular agreement | Plural agreement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. v-class | k'ant (boy) | v- | b- / d- | k'ant v-eza v-u 'the boy is heavy' | k'entii d-eza d-u 'the boys are heavy' |

| 2. y-class | zuda (woman) | y- | b- / d- | zuda y-eza y-u 'the woman is heavy' | zudari b-eza b-u 'the women are heavy |

| 3. y-class II | ph'āgal (rabbit) | y- | y- | ph'āgal y-eza y-u 'the rabbit is heavy' | ph'āgalash y-eza y-u 'the rabbits are heavy' |

| 4. d-class | naž (oak) | d- | d- | naž d-eza d-u 'the oak is heavy' | niežnash d-eza d-u 'the oaks are heavy' |

| 5. b-class | mangal (scythe) | b- | b- / Ø- | mangal b-eza b-u 'the scythe is heavy' | mangalash b-eza b-u 'the scythes are heavy' |

| 6. b-class II | ˤaž (apple) | b- | d- | ˤaž b-eza b-u 'the apple is heavy' | ˤežash d-eza d-u 'the apples are heavy' |

When a noun denotes a human being, it usually falls into v- or y-Classes (1 or 2). Most nouns referring to male entities fall into the v-class, whereas Class 2 contains words related to female entities. Thus lūlaxuo (a neighbour) is class 1, but takes v- if a male neighbour and y- if a female. In a few words, changing the prefixes before the nouns indicates grammatical gender; thus: vоsha (brother) → yisha (sister). Some nouns denoting human beings, however, are not in Classes 1 or 2: bēr (child) for example is in class 3.

Classed adjectives

Only a few of Chechen's adjectives index noun class agreement, termed classed adjectives in the literature. Classed adjectives are listed with the -d class prefix in the romanizations below:[10]

- деза/d-eza ‘heavy’

- довха/d-ouxa ‘hot’

- деха/d-iexa ‘long’

- дуькъа/d-yq’a ‘thick’

- дораха/d-oraxa ‘cheap’

- дерстана/d-erstana ‘fat’

- дуьткъа/d-ytq’a thin’

- доца/d-oca ‘short’

- дайн/d-ain ‘light’

- дуьзна/d-yzna ‘full’

- даьржана/d-aerzhana ‘spread’

- доккха/d-oqqa ‘large/big/old’

Declension

Whereas Indo-European languages code noun class and case conflated in the same morphemes, Chechen nouns show no gender marking but decline in eight grammatical cases, four of which are core cases (i.e. absolutive, ergative, genitive, and dative) in singular and plural. Below the paradigm for "говр" (horse).

| Case | singular | plural |

|---|---|---|

| absolutive | говр gour | говраш gourash |

| genitive | говран gouran | говрийн gouriin |

| dative | говрана gour(a)na | говрашна gourashna |

| ergative | говро gouruo | говраша gourasha |

| allative | говре gourie | говрашка gourashka |

| instrumental | говраца gouratsa | говрашца gourashtsa |

| locative | говрах gourax | говрех gouriäx |

| comparative | говрал goural | говрел gouriäl |

Pronouns

| Case | 1SG | IPA | 2SG | IPA | 3SG | IPA | 1PL Inclusive | IPA | 1PL Exclusive | IPA | 2PL | IPA | 3PL | IPA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| absolutive | со | /sʷɔ/ | хьо | /ʜʷɔ/ | и, иза | /ɪ/, /ɪzə/ | вай | /vəɪ/ | тхо | /txʷʰo/ | шу | /ʃu/ | уьш, уьзаш | /yʃ/, /yzəʃ/ |

| genitive | сан | /sən/ | хьан | /ʜən/ | цуьнан | /tsʰynən/ | вайн | /vəɪn/ | тхан | /txʰən/ | шун | /ʃun/ | церан | /tsʰierən/ |

| dative | суна | /suːnə/ | хьуна | /ʜuːnə/ | цунна | /tsʰunːə/ | вайна | /vaɪnə/ | тхуна | /txʰunə/ | шуна | /ʃunə/ | царна | /tsʰarnə/ |

| ergative | ас | /ʔəs/ | ахь | /əʜ/ | цо | /tsʰuo/ | вай | /vəɪ/ | оха | /ʔɔxə/ | аша | /ʔaʃə/ | цара | /tsʰarə/ |

| allative | соьга | /sɥœgə/ | хьоьга | /ʜɥœgə/ | цуьнга | /tsʰyngə/ | вайга | /vaɪgə/ | тхоьга | /txʰɥœgə/ | шуьга | /ʃygə/ | цаьрга | /tsʰærgə/ |

| instrumental | соьца | /sɥœtsʰə/ | хьоьца | /ʜɥœtsʰə/ | цуьнца | /tsʰyntsʰə/ | вайца | /vaɪtsʰə/ | тхоьца | /txʰɥœtsʰə/ | шуьца | /ʃytsʰə/ | цаьрца | /tsʰærtsʰə |

| locative | сох | /sʷɔx/ | хьох | /ʜʷɔx/ | цунах | /tsʰunəx/ | вайх | /vəɪx/ | тхох | /txʰʷɔx/ | шух | /ʃux/ | царах | /tsʰarəx/ |

| comparative | сол | /sʷɔl/ | хьол | /ʜʷɔl/ | цул | /tsʰul/ | вайл | /vəɪl/ | тхол | /txʰʷɔl/ | шул | /ʃul/ | царел | /tsʰarɛl/ |

Possessive pronouns

| 1SG | 2SG | 3SG | 1PL inclusive | 1PL exclusive | 2PL | 3PL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| reflexive possessive pronouns | сайн | хьайн | шен | вешан | тхайн | шайн | шайн |

| substantives (mine, yours) | сайниг | хьайниг | шениг | вешаниг | тхайниг | шайниг | шайниг |

The locative still has a few further forms for specific positions

Verbs

Verbs do not inflect for person (except for the special d- prefix for the 1st and 2nd persons plural), only for number and tense, aspect, mood. A minority of verbs exhibit agreement prefixes, and these agree with either their subject (intransitive verbs) or with their objects (transitive verbs), with the important note that verbs in compound continuous tenses have the auxiliary verb (-u, to be) agree with the subject and the main verb in participial form agree with the object, provided that the subject is left in the absolutive case (unmarked). If the subject of a transitive verb is marked ergative case, then the auxiliary can only agree with the direct object of the verb.

Example of verbal agreement in intransitive clause with a composite verb:

Со цхьан сахьтехь вогІур ву (so tsHan saHteH voghur vu) = I (male) will come in one hour

Со цхьан сахьтехь йогІур ю (so tsHan saHteH yoghur yu) = I (female) will come in one hour

Where the verb's future stem "-огІур" (will come) and the auxiliary "-у" (present tense of 'be') receive the prefix v- for a masculine subject but y- for a feminine subject.

Verbal tenses are formed by ablaut or suffixes, or both (there are five conjugations in total, below is one). Derived stems can be formed by suffixation as well (causative, etc.):

| Tense | Example |

|---|---|

| Imperative (=infinitive) | д*ига |

| simple present | д*уьгу |

| present composite | д*уьгуш д*у |

| near preterite | д*игу |

| witnessed past | д*игира |

| perfect | д*игна |

| plusquamperfect | д*игнера |

| repeated preterite | д*уьгура |

| possible future | д*уьгур |

| real future | д*уьгур д*у |

| Tempus | Basic form ("drink") | Causative ("make drink, drench") | Permissive ("allow to drink") | Permissive causative ("allow to make drink") | Potential ("be able to drink") | Inceptive ("start drinking") |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imperative (=infinitive) | мала | мало | малийта | малад*айта | малад*ала | малад*āла |

| simple present | молу | малад*о | молуьйто | малад*ойту | малало | малад*олу |

| near preterite | малу | малий | малийти | малад*айти | малад*ели | малад*ēли |

| witnessed past | мелира | малийра | малийтира | малад*айтира | малад*елира | малад*ēлира |

| perfect | мелла | малийна | малийтина | малад*айтина | малад*елла | малад*аьлла |

| plusquamperfect | меллера | малийнер | малийтинера | малад*айтинера | малад*елера | малад*аьллера |

| repeated past | молура | малад*ора | молуьйтура | малад*ойтура | малалора | |

| possible future | молур | малад*ер | молуьйтур | малад*ойтур | малалур | малад*олур |

| real future | молур д*у | малад*ийр д*у | молуьйтур д*у | малад*ойтур д*у | малалур д*у | малад*олур д*у |

Alphabets

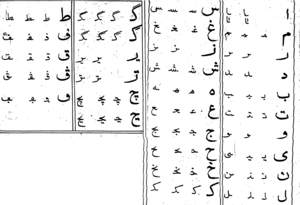

Numerous inscriptions in the Georgian script are found in mountainous Chechnya, but they are not necessarily in Chechen. Later, the Arabic script was introduced for Chechen, along with Islam. The Chechen Arabic alphabet was first reformed during the reign of Imam Shamil, and then again in 1910, 1920 and 1922.

At the same time, the alphabet devised by Peter von Uslar, consisting of Cyrillic, Latin, and Georgian letters, was used for academic purposes. In 1911 it too was reformed but never gained popularity among the Chechens themselves.

The Latin alphabet was introduced in 1925. It was unified with Ingush in 1934, but abolished in 1938.

| A a | Ä ä | B b | C c | Č č | Ch ch | Čh čh | D d |

| E e | F f | G g | Gh gh | H h | I i | J j | K k |

| Kh kh | L l | M m | N n | Ņ ņ | O o | Ö ö | P p |

| Ph ph | Q q | Qh qh | R r | S s | Š š | T t | Th th |

| U u | Ü ü | V v | X x | Ẋ ẋ | Y y | Z z | Ž ž |

In 1938–92, only the Cyrillic alphabet was used for Chechen.

| Cyrillic | Name | Arabic (before 1925) |

Modern Latin |

Name | IPA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| А а | а | آ /ɑː/, ا | A a | a | /ə/, /ɑː/ |

| Аь аь | аь | ا | Ä ä | ä | /æ/, /æː/ |

| Б б | бэ | ب | B b | be | /b/ |

| В в | вэ | و | V v | ve | /v/ |

| Г г | гэ | گ | G g | ge | /ɡ/ |

| Гӏ гӏ | гӏа | غ | Ġ ġ | ġa | /ɣ/ |

| Д д | дэ | د | D d | de | /d/ |

| Е е | е | ە | E e | e | /e/, /ɛː/, /je/, /ie/ |

| Ё ё | ё | یوٓ | yo | /jo/ etc. | |

| Ж ж | жэ | ج | Ƶ ƶ | ƶe | /ʒ/, /dʒ/ |

| З з | зэ | ز | Z z | ze | /z/, /dz/ |

| И и | и | ی | I i | i | /ɪ/ |

| Ий ий | یی | Iy iy | /iː/ | ||

| Й й (я, ю, е) | доца и | ی | Y y | doca i | /j/ |

| К к | к | ک | K k | ka | /k/ |

| Кк кк | کک | Kk kk | /kː/ | ||

| Кх кх | кх | ق | Q q | qa | /q/ |

| Ккх ккх | قق | Qq qq | /qː/ | ||

| Къ къ | къа | ڨ | Q̇ q̇ | q̇a | /qʼ/ |

| Кӏ кӏ | кӏа | گ (ࢰ)[lower-alpha 1] | Kh kh | kha | /kʼ/ |

| Л л | лэ | ل | L l | el | /l/ |

| М м | мэ | م | M m | em | /m/ |

| Н н | нэ | ن | N n | en | /n/ |

| О о | о | ووٓ, وٓ uo | O o | o | /o/, /ɔː/, /wo/, /uo/ |

| Ов ов | ов | وٓو | Ov ov | ov | /ɔʊ/ |

| Оь оь | оь | وٓ | Ö ö | ö | /ɥø/, /yø/ |

| П п | пэ | ف | P p | pe | /p/ |

| Пп пп | فف | Pp pp | /pː/ | ||

| Пӏ пӏ | пӏа | ڢ ـٯ | Ph ph | pha | /pʼ/ |

| Р р | рэ | ر | R r | er | /r/ |

| Рхӏ рхӏ | رھ | Rh rh | /r̥/ | ||

| С с | сэ | س | S s | es | /s/ |

| Сс сс | سس | Ss ss | /sː/ | ||

| Т т | тэ | ت | T t | te | /t/ |

| Тт тт | تت | Tt tt | /tː/ | ||

| Тӏ тӏ | тӏа | ط | Th th | tha | /tʼ/ |

| У у | у | و | U u | u | /uʊ/ |

| Ув ув | وو | Uv uv | /uː/ | ||

| Уь уь | уь | و | Ü ü | ü | /y/ |

| Уьй уьй | уьй | و | Üy üy | üy | /yː/ |

| Ф ф | фэ | ف | F f | ef | /f/ |

| Х х | хэ | خ | X x | xa | /x/ |

| Хь хь | хьа | ح | Ẋ ẋ | ẋa | /ʜ/ |

| Хӏ хӏ | хӏа | ھ | H h | ha | /h/ |

| Ц ц | цэ | ر̤ [lower-alpha 2] | C c | ce | /ts/ |

| Цӏ цӏ | цӏа | ڗ | Ċ ċ | ċe | /tsʼ/ |

| Ч ч | чэ | چ | Ҫ ҫ | ҫe | /tʃ/ |

| Чӏ чӏ | чӏа | ڃ | Ҫ̇ ҫ̇ | ҫ̇e | /tʃʼ/ |

| Ш ш | шэ | ش | Ş ş | şa | /ʃ/ |

| Щ щ | щэ | ||||

| (Ъ) ъ[lower-alpha 3] | чӏогӏа хьаьрк | ئ | Ə ə[lower-alpha 3] | ç̇oġa ẋärk | /ʔ/ |

| (Ы) ы | ы | ||||

| (Ь) ь | кӏеда хьаьрк | kheda ẋärk | |||

| Э э | э | اە | E e | e | /e/ etc. |

| Ю ю | ю | یو | yu | /ju/ etc. | |

| Юь юь | юь | یو | yü | /jy/ etc. | |

| Я я | я | یا، یآ | ya | /ja/ etc. | |

| Яь яь | яь | یا | yä | /jæ/ etc. | |

| Ӏ ӏ | ӏа | ع | J j | ja | /ʡ/, /ˤ/ |

Notes

In 1992, a new Latin Chechen alphabet was introduced, but after the defeat of the secessionist government, the Cyrillic alphabet was restored.

| A a | Ä ä | B b | C c | Ċ ċ | Ç ç | Ç̇ ç̇ | D d |

| E e | F f | G g | Ġ ġ | H h | X x | Ẋ ẋ | I i |

| J j | K k | Kh kh | L l | M m | N n | Ꞑ ꞑ | O o |

| Ö ö | P p | Ph ph | Q q | Q̇ q̇ | R r | S s | Ş ş |

| T t | Th th | U u | Ü ü | V v | Y y | Z z | Ƶ ƶ |

| Ə ə |

Vocabulary

Most Chechen vocabulary is derived from the Nakh branch of the Northeast Caucasian language family, although there are significant minorities of words derived from Arabic (Islamic terms, like "Iman", "Ilma", "Do'a") and a smaller amount from Turkic (like "kuzga", "shish"), belonging to the universal Caucasian stratum of borrowings) and most recently Russian (modern terms, like computer – "kamputar", television – "telvideni", televisor – "telvizar", metro – "metro" etc.).

History

Before the Russian conquest, most writing in Chechnya consisted of Islamic texts and clan histories, written usually in Arabic but sometimes also in Chechen using Arabic script. Those texts were largely destroyed by Soviet authorities in 1944. The Chechen literary language was created after the October Revolution, and the Latin script began to be used instead of Arabic for Chechen writing in the mid-1920s. In 1938, the Cyrillic script was adopted, in order to tie the nation closer to Russia. With the declaration of the Chechen republic in 1992, some Chechen speakers returned to the Latin alphabet.

The Chechen diaspora in Jordan, Turkey, and Syria is fluent but generally not literate in Chechen except for individuals who have made efforts to learn the writing system, and of course the Cyrillic alphabet is not generally known in these countries.

The choice of alphabet for Chechen is politically significant: Russia prefers the use of Cyrillic, whereas the separatists preferred Latin.

References

- 1 2 Chechen at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Chechen". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ Constitution, Article 10.1

- ↑ Moshe Maʻoz, Gabriel Sheffer (2002). Middle Eastern minorities and diasporas. Sussex Academic Press. p. 255. ISBN 1-902210-84-0. Retrieved May 12, 2011.

- ↑ Johanna Nichols, Chechen, The Indigenous languages of the Caucasus (Caravan Books, Delmar NY, 1994) ISBN 0-88206-068-6.

- ↑ "Indigenous Language of the Caucasus (Chechen)". Ingush.narod.ru. pp. 10–11. Archived from the original (GIF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2016-01-21.

- ↑ Awde, Nicholas and Galäv, Muhammad, Chechen; p. 11. ISBN 0-7818-0446-9

- ↑ Awde and Galäv; Chechen; p. 11

- ↑ Awde, Nicholas; Galaev, Muhammad (22 May 2014). "Chechen-English English-Chechen Dictionary and Phrasebook". Routledge – via Google Books.

- ↑ Dotton & Doyle Wagner, Zura & John. A grammar of Chechen.

Sources

- Pieter Muysken (6 February 2008). From Linguistic Areas to Areal Linguistics. John Benjamins Publishing Company. pp. 29, 46, 47, 49, 52–54, 56, 58, 60, 61, 63, 70–74, 77, 93. ISBN 978-90-272-9136-3.

External links

| Chechen edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: Chechen |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Chechen phrasebook. |

- Appendix:Cyrillic script

- A Grammar of Chechen

- The Cyrillic and Latin Chechen alphabets

- The Chechen language | Noxchiin mott Wealth of linguistic information.

- Rferl North Caucasus Radio (also includes Avar and Adyghe)

- Russian–Chechen on-line dictionary

- Chechen basic lexicon at the Global Lexicostatistical Database

- Chechen Cyrillic - Latin converter

- ELAR archive of Chechen including the Cheberloi dialect