Ethnic groups in Europe

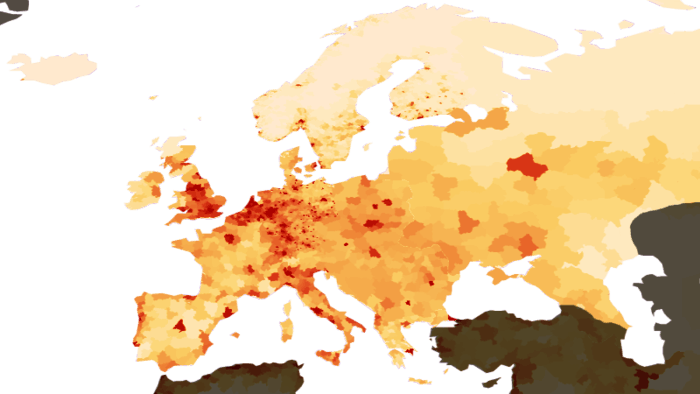

The indigenous peoples of Europe are the focus of European ethnology, the field of anthropology related to the various indigenous groups that reside in the nations of Europe. According to German monograph Minderheitenrechte in Europa co-edited by Pan and Pfeil (2002) there are 87 distinct peoples of Europe, of which 33 form the majority population in at least one sovereign state, while the remaining 54 constitute ethnic minorities. The total number of national or linguistic minority populations in Europe is estimated at 105 million people, or 14% of 770 million Europeans.[1]

There is some precise or universally accepted definition of the terms "ethnic group" or "nationality". In the context of European ethnography in particular, the terms ethnic group, people, nationality or ethno-linguistic group, are used as mostly synonymous, although preference may vary in usage with respect to the situation specific to the individual countries of Europe.[2]

Overview

There are eight European ethno-linguistic groups with more than 30 million members residing in Europe. These eight groups between themselves account for some 465 million or about 65% of European population:

.svg.png)

Smaller ethno-linguistic groups with more than 10 million people residing in Europe include:

.svg.png)

About 20–25 million residents (3%) are members of diasporas of non-European origin. The population of the European Union, with some five hundred million residents, accounts for two thirds of the European population.

Both Spain and the United Kingdom are special cases, in that the designation of nationality, Spanish and British, may controversially take ethnic aspects, subsuming various regional ethnic groups, see nationalisms and regionalisms of Spain and native populations of the United Kingdom. Switzerland is a similar case, but the linguistic subgroups of the Swiss are discussed in terms of both ethnicity and language affiliations.

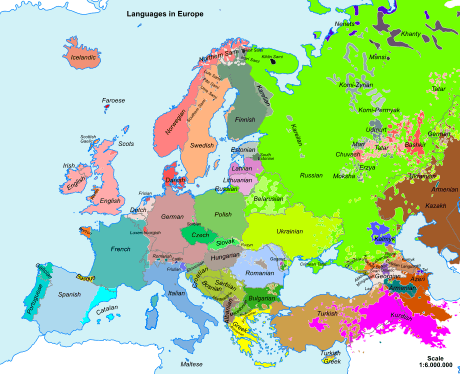

Linguistic classifications

Of the total population of Europe of some 740 million (as of 2010), close to 90% (or some 650 million) fall within three large branches of Indo-European languages, these being;

- Balto-Slavic, including Russian, Ukrainian, Polish, Croatian, Macedonian, Czech, Bosnian, Bulgarian, Slovenian, Serbian, Slovak, Belarusian, Ruthenian, Latvian, and Lithuanian.

- Romance, including; Italian, French, Spanish, Romanian, Portuguese, Catalan, Corsican, Friulian, Aromanian, Walloon, Romansh, Latin, and Sardinian.

- Germanic, including; English, German, Dutch, Swedish, Danish, Norwegian, Flemish, Luxembourgish, Icelandic, Frisian, Limburgish, Low Saxon and Faeroese. Afrikaans, a daughter language of Dutch, is spoken by some South African and Namibian migrant populations.

Three stand-alone Indo-European languages do not fall within larger sub-groups and are not closely related to those larger language families;

In addition, there are also smaller sub-groups within the Indo-European languages of Europe, including;

- Celtic (including Welsh, Breton, Irish Gaelic, Scots Gaelic, Cornish and Manx)

- Iranic, mainly Ossetian in Europe, as well as Kurdish (spoken mainly in Turkey)

- Indo-Aryan is represented by the Romani language spoken by Roma people of eastern Europe, and is at root related to the Indo-Aryan languages of the Indian sub-Continent.

Besides the Indo-European languages, there are other language families on the European continent which are wholly unrelated to Indo-European:

- Uralic languages, including; Hungarian, Finnish, Estonian, Mordvin, Samoyedic, Sami, Komi, Udmurt and Mari.

- Turkic languages, including; Turkish, Azeri, Tatar, Nogai, Bashkir and Chuvash.

- Semitic languages, including; Maltese, Assyrian Neo-Aramaic spoken in parts of eastern Turkey and the Caucasus by Assyrian Christians, and Hebrew, the latter spoken by some Jewish populations.

- Kartvelian languages (also known as South Caucasian languages), including Georgian, Mingrelian, Zan, Svan and Laz.

- Northwest Caucasian languages, including; Circassian, Kabardian, Ubykh, Adyghe, Abkhaz and Abaza.

- Northeast Caucasian languages, including; Chechen, Avar, Lak, Lezgian, Ingush and Nakho-Dagestanian.

- Language isolates; Basque, spoken in the Basque regions of Spain and France is an isolate language, the only one in Europe, and is unrelated to any other language, living or extinct.

- Mongolic languages exist in the form of Kalmyk spoken in the Caucasus region of Russia.

History

Prehistoric populations

The Basques have been found to descend from the population of the late Neolithic or early Bronze Age directly.[5][6] The Indo-European groups of Europe (the Centum groups plus Balto-Slavic and Albanian) are assumed to have developed in situ by admixture of Bronze Age, proto-Indo-European groups with earlier Mesolithic and Neolithic populations, after migrating to most of Europe from the Pontic steppe (Yamna culture, Corded ware, Beaker people).[7][8][9] The Finnic peoples are assumed to also be descended from Proto-Uralic populations further to the east, nearer to the Ural Mountains, that had migrated to their historical homelands in Europe by about 3,000 years ago.[10]

Reconstructed languages of Iron Age Europe include Proto-Celtic, Proto-Italic and Proto-Germanic, all of these Indo-European languages of the centum group, and Proto-Slavic and Proto-Baltic, of the satem group. A group of Tyrrhenian languages appears to have included Etruscan, Rhaetian and perhaps also Eteocretan and Eteocypriot. A pre-Roman stage of Proto-Basque can only be reconstructed with great uncertainty.

Regarding the European Bronze Age, the only secure reconstruction is that of Proto-Greek (ca. 2000 BC). A Proto-Italo-Celtic ancestor of both Italic and Celtic (assumed for the Bell beaker period), and a Proto-Balto-Slavic language (assumed for roughly the Corded Ware horizon) has been postulated with less confidence. Old European hydronymy has been taken as indicating an early (Bronze Age) Indo-European predecessor of the later centum languages.

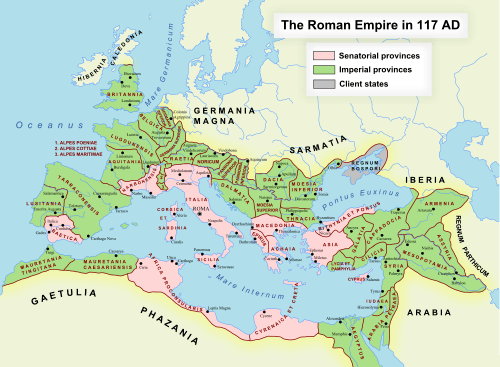

Historical populations

Iron Age (pre-Great Migrations) populations of Europe known from Greco-Roman historiography, notably Herodotus, Pliny, Ptolemy and Tacitus:

- Aegean: Greek tribes, Pelasgians/Tyrrhenians, and Anatolians.

- Balkans: Illyrians (List of ancient tribes in Illyria), Dacians, and Thracians.

- Italian peninsula: Italic peoples, Etruscans, Adriatic Veneti, Ligurians and Greek colonies.

- Western/Central Europe: Celts (list of peoples of Gaul, List of Celtic tribes), Rhaetians and Swabians, Vistula Veneti, Lugii and Balts.

- Iberian peninsula: Pre-Roman peoples of the Iberian Peninsula (Iberians, Lusitani, Aquitani, Celtiberians) Basques and Phoenicians ( Carthaginians).

- Sardinia: ancient Sardinians (also known as Nuragic people), comprising the Corsi, Balares and Ilienses tribes.

- West European Isles: Celtic tribes in Britain and Ireland and Picts/Priteni.

- Northern Europe: Finnic peoples, Germanic peoples (list of Germanic peoples).

- Southern Europe: Sicani.

- Eastern Europe: Scythians, Sarmatians.

Historical immigration

Ethno-linguistic groups that arrived from outside Europe during historical times are:

- Phoenician colonies in the Mediterranean (including regions in Spain, France, Malta, Italy and the Aegean), from about 1200 BC to the fall of Carthage after the Third Punic War in 146 BC.

- Assyrian conquest of Cyprus, Southern Caucasus (including parts of modern Armenia, Georgia and Azerbaijan) and Cilicia during the Neo-Assyrian Empire (911-605 BC)

- Iranian influence: Achaemenid control of Thrace (512–343 BC) and the Bosporan Kingdom, Cimmerians (possible Iranians), Scythians, Sarmatians, Alans, Ossetes.

- the Jewish diaspora reached Europe in the Roman Empire period, the Jewish community in Italy dating to around AD 70 and records of Jews settling Central Europe (Gaul) from the 5th century (see History of the Jews in Europe).

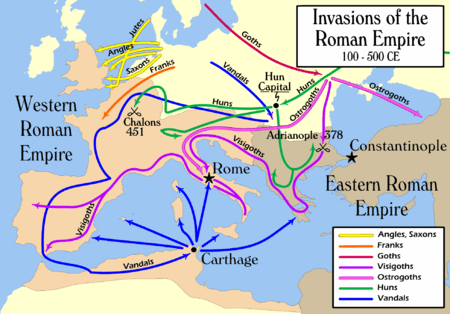

- The Hunnic Empire (5th century), converged with the Barbarian invasions, contributing to the formation of the First Bulgarian Empire

- Avar Khaganate (c.560s-800), converged with the Slavic migrations, fused into the South Slavic states from the 9th century.

- the Bulgars (or Proto-Bulgarians), a semi-nomadic people, originally from Central Asia, eventually absorbed by the Slavs.

- the Magyars (Hungarians), a Ugric people, and the Turkic Pechenegs and Khazars, arrived in Europe in about the 8th century (see Hungarian conquest of the Carpathian Basin).

- the Arabs conquered Cyprus, Crete, Sicily, some places along the coast of southern Italy, Malta, Greek Empire, Hispania and, in the early 11th century, Emirate of Sicily (831–1072, expelled in 1224) and Al-Andalus (711–1492, expelled)

- the Berber dynasties of the Almoravides and the Almohads ruled much of Spain and Portugal.[11]

- exodus of Maghreb Christians[12]

- the western Kipchaks known as Cumans entered the lands of present-day Ukraine in the 11th century.

- the Mongol/Tatar invasions (1223–1480), and Ottoman control of the Balkans (1389–1878). These medieval incursions account for the presence of European Turks and Tatars.

- the Romani people (Gypsies) arrived during the Late Middle Ages

- the Mongol Kalmyks arrived in Kalmykia in the 17th century.

History of European ethnography

%2C_ethnic_groups.jpg)

The earliest accounts of European ethnography date to Classical Antiquity. Herodotus described the Scythians and Thraco-Illyrians. Dicaearchus gave a description of Greece itself besides accounts of western and northern Europe. His work survives only fragmentarily, but was received by Polybius and others.

Roman Empire period authors include Diodorus Siculus, Strabo and Tacitus. Julius Caesar gives an account of the Celtic tribes of Gaul, while Tacitus describes the Germanic tribes of Magna Germania. A number of authors like Diodorus Siculus, Pausanias and Sallust depicts the ancient Sardinian and Corsican peoples.

The 4th century Tabula Peutingeriana records the names of numerous peoples and tribes. Ethnographers of Late Antiquity such as Agathias of Myrina Ammianus Marcellinus, Jordanes or Theophylact Simocatta give early accounts of the Slavs, the Franks, the Alamanni and the Goths.

Book IX of Isidore's Etymologiae (7th century) treats de linguis, gentibus, regnis, militia, civibus (of languages, peoples, realms, armies and cities). Ahmad ibn Fadlan in the 10th century gives an account of the Bolghar and the Rus' peoples. William Rubruck, while most notable for his account of the Mongols, in his account of his journey to Asia also gives accounts of the Tatars and the Alans. Saxo Grammaticus and Adam of Bremen give an account of pre-Christian Scandinavia. The Chronicon Slavorum (12th century) gives an account of the northwestern Slavic tribes.

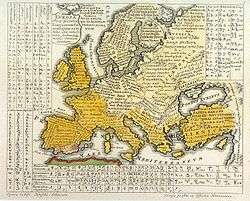

Gottfried Hensel in his 1741 Synopsis Universae Philologiae published what is probably the earliest ethno-linguistic map of Europe, showing the beginning of the pater noster in the various European languages and scripts.[13][14] In the 19th century, ethnicity was discussed in terms of scientific racism, and the ethnic groups of Europe were grouped into a number of "races", Mediterranean, Alpine and Nordic, all part of a larger "Caucasian" group.

The beginnings of ethnic geography as an academic subdiscipline lie in the period following World War I, in the context of nationalism, and in the 1930s exploitation for the purposes of fascist and Nazi propaganda so that it was only in the 1960s that ethnic geography began to thrive as a bona fide academic subdiscipline.[15]

The origins of modern ethnography are often traced to the work of Bronisław Malinowski who emphasized the importance of fieldwork.[16] The emergence of population genetics further undermined the categorisation of Europeans into clearly defined racial groups. A 2007 study on the genetic history of Europe found that the most important genetic differentiation in Europe occurs on a line from the north to the south-east (northern Europe to the Balkans), with another east-west axis of differentiation across Europe, separating the "indigenous" Basques and Sami from other European populations. Despite these stratifications it noted the unusually high degree of European homogeneity: "there is low apparent diversity in Europe with the entire continent-wide samples only marginally more dispersed than single population samples elsewhere in the world."[17][18][19]

Minorities

The total number of national minority populations in Europe is estimated at 105 million people, or 14% of Europeans.[1]

The member states of the Council of Europe in 1995 signed the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities. The broad aims of the Convention are to ensure that the signatory states respect the rights of national minorities, undertaking to combat discrimination, promote equality, preserve and develop the culture and identity of national minorities, guarantee certain freedoms in relation to access to the media, minority languages and education and encourage the participation of national minorities in public life. The Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities defines a national minority implicitly to include minorities possessing a territorial identity and a distinct cultural heritage. By 2008, 39 member states have signed and ratified the Convention, with the notable exception of France.

Non-indigenous minorities

Many non-European ethnic groups and nationalities have immigrated to Europe over the centuries. Some arrived centuries ago, while others immigrated more recently in the 20th century, often from former colonies of the British, Dutch, French, Portuguese and Spanish empires.

- Western Asians

- Jews: approx. 2.0 million, mostly in France, the UK and Germany. They are descended from the Israelites of the Middle East (Southwest Asia),[20][21][22][23][24][25][26] originating from the historical kingdoms of Israel and Judah.[27][28][29][30]

- Ashkenazi Jews: approx. 1.4 million, mostly in the United Kingdom, Germany, France and Ukraine. They are believed by scholars to have arrived from Israel via southern Europe[31][32][33][34][35] in the Roman era[36] and settled in France and Germany towards the end of the first millennium. The Nazi Holocaust wiped out the vast majority during World War II and forced many to flee.

- Sephardi Jews: approx. 0.3 million, mostly in France. They arrived via Spain and Portugal in the pre-Roman[37] and Roman[38] eras, and were forcibly converted or expelled in the 15th and 16th centuries.

- Mizrahi Jews: approx. 0.3 million, mostly in France, via Islamic-majority countries of the Middle East.

- Italqim: approx. 50,000, mostly in Italy, since the 2nd century BC.

- Romaniotes: approx. 6,000, mostly in Greece, with communities dating at least from the 1st century AD.

- Crimean Karaites (Karaim): less than 4,000, mostly in Ukraine, Poland and Lithuania. They arrived in Crimea in the Middle Ages.

- Assyrians: mostly in Sweden and Germany, as well in Russia, Armenia, Denmark and Great Britain (see Assyrian diaspora). Assyrians have been present in Eastern Turkey since the Bronze Age (circa 2000 BCE).

- Kurds: approx. 2.5 million, mostly in the UK, Germany, Sweden and Turkey.

- Iraqi diaspora: mostly in the UK, Germany and Sweden, and can be of varying ethnic origin, including Arabs, Assyrians, Kurds, Armenians, Shabaks, Mandeans, Turcoman, Kawliya and Yezidis.

- Lebanese diaspora: especially in France, Netherlands, Germany, Cyprus and the UK.[39]

- Syrian diaspora: Largest number of Syrians live in Germany, the Netherlands and Sweden and can be of varying ethnic origin, including; Arabs, Assyrians, Kurds, Armenians, Arameans, Turcoman, Mhallami and Yezidis.

- Jews: approx. 2.0 million, mostly in France, the UK and Germany. They are descended from the Israelites of the Middle East (Southwest Asia),[20][21][22][23][24][25][26] originating from the historical kingdoms of Israel and Judah.[27][28][29][30]

- Africans

- North Africans (Arabs and Berbers): approx. 5 million, mostly in France, Spain, Italy, the Netherlands and Sweden. The bulk of North African migrants are Moroccans, although France also has a large number of Algerians, and others may be from Egypt (including Copts), Libya and Tunisia.

- Horn Africans (Somalis, Ethiopians, Eritreans, Djiboutians, and the Northern Sudanese): approx. 700,000, mostly in Scandinavia, the UK, the Netherlands, Germany, Switzerland, Austria, Finland, and Italy. Majority arrived to Europe as refugees. Proportionally few live in Italy despite former colonial ties, most live in the Nordic countries.

- Sub-Saharan Africans (many ethnicities including Afro-Caribbeans and others by descent): approx. 5 million, mostly in the UK and France, with smaller numbers in the Netherlands, Germany, Italy, Spain, Portugal and elsewhere.[40]

- Latin Americans: approx. 2.2 million, mainly in Spain and to a lesser extent Italy and the UK.[41] See also Latin American Britons (80,000 Latin American born in 2001).[42]

- Brazilians: around 70,000 in Portugal and Italy each, and 50,000 in Germany.

- Chilean refugees escaping the Augusto Pinochet regime of the 1970s formed communities in France, Sweden, the UK, former East Germany and the Netherlands.

- Venezuelans: around 520,000 mostly in Spain (200,000), Portugal (100,000), France (30,000), Germany (20,000), UK (15,000), Ireland (5,000), Italy (5,000) and the Netherlands (1,000).

- South Asians: approx. 3–4 million, mostly in the UK but reside in smaller numbers in Germany and France.

- Romani (Gypsies): approx. 4 or 10 million (although estimates vary widely), dispersed throughout Europe but with large numbers concentrated in the Balkans area, they are of ancestral South Asian and European descent,[43] originating from the northern regions of the Indian subcontinent.

- Indians: approx. 2 million, mostly in the UK, also in Italy, in Germany and smaller numbers in Ireland.

- Pakistanis: approx. 1,000,000, mostly in the UK and in Italy, but also in Norway and Sweden.

- Tamils: approx. 250,000, predominantly in the UK.

- Bangladeshi residing in Europe estimated at over 500,000, mostly in the UK and in Italy.

- Sri Lankans: approx. 200,000, mainly in the UK and in Italy

- Nepalese: approx. 50,000 in the UK

- Afghans, about 100,000 to 200,000, most happen to live in the UK, but Germany and Sweden are destinations for Afghan immigrants since the 1960s.

- Southeast Asians

- Filipinos: above 1 million, mostly in Italy, the UK, France, Germany, Spain.

- Others of multiple nationalities, ca. total 1 million, such as Indonesians in the Netherlands, Thais in the UK and Sweden, Vietnamese in France and former East Germany, and Cambodians in France, together with Burmese, Malaysian, Singaporean, Timorese and Laotian migrants. See also Vietnamese people in the Czech Republic.

- East Asians

- Chinese: approx. 1.7 million, mostly in France, Russia, the UK, Spain, Italy and the Netherlands.

- Japanese: mostly in the UK and a sizable community in Düsseldorf, Germany.

- Koreans: 100,000 estimated (excludes a possible 100,000 more in Russia), mainly in the UK, France and Germany. See also Koryo-saram.

- Mongolians are a sizable community in Germany, Poland and the Czech Republic.

- North Americans

- U.S. and Canadian expatriates: American British and Canadian British, Canadiens and Acadians in France, as well Americans/Canadians of European ancestry residing elsewhere in Europe.

- African Americans (i.e. African American British) who are Americans of black/African ancestry reside in other countries. In the 1920s, African-American entertainers established a colony in Paris (African American French) and descendants of World War II/Cold War-era black American soldiers stationed in France, Germany and Italy are well known.

- U.S. and Canadian expatriates: American British and Canadian British, Canadiens and Acadians in France, as well Americans/Canadians of European ancestry residing elsewhere in Europe.

- Others

- European diaspora – Australians, New Zealanders, South Africans (mostly White South Africans of Afrikaaner and British descent), and white Namibians, Zimbabweans, Kenyans, Malawians and Zambians mainly in the UK, together with white Angolans and Mozambicans, mainly of Portuguese descent.

- Pacific Islanders: A small population of Tahitians of Polynesian origin in mainland France, Fijians in the United Kingdom from Fiji and Māori in the United Kingdom of the Māori people of New Zealand, a small number of Tongans and Samoans, also in the United Kingdom.

- Amerindians and Inuit, a scant few in the European continent of American Indian ancestry (often Latin Americans in Spain, France and the UK; Inuit in Denmark), but most may be children or grandchildren of U.S. soldiers from American Indian tribes by intermarriage with local European women. An estimated 60,000 American Indians may live in Germany as of the 2010s.

European identity

Historical

Medieval notions of a relation of the peoples of Europe are expressed in terms of genealogy of mythical founders of the individual groups. The Europeans were considered the descendants of Japheth from early times, corresponding to the division of the known world into three continents, the descendants of Shem peopling Asia and those of Ham peopling Africa. Identification of Europeans as "Japhetites" is also reflected in early suggestions for terming the Indo-European languages "Japhetic".

In this tradition, the Historia Brittonum (9th century) introduces a genealogy of the peoples of the Migration period (as it was remembered in early medieval historiography) as follows,

- The first man that dwelt in Europe was Alanus, with his three sons, Hisicion, Armenon, and Neugio. Hisicion had four sons, Francus, Romanus, Alamanus, and Bruttus. Armenon had five sons, Gothus, Valagothus, Cibidus, Burgundus, and Longobardus. Neugio had three sons, Vandalus, Saxo, and Boganus.

- From Hisicion arose four nations—the Franks, the Latins, the Germans, and Britons; from Armenon, the Gothi, Valagothi, Cibidi, Burgundi, and Longobardi; from Neugio, the Bogari, Vandali, Saxones, and Tarincgi. The whole of Europe was subdivided into these tribes.[44]

The text goes then on to list the genealogy of Alanus, connecting him to Japheth via eighteen generations.

European culture

European culture is largely rooted in what is often referred to as its "common cultural heritage".[45] Due to the great number of perspectives which can be taken on the subject, it is impossible to form a single, all-embracing conception of European culture.[46] Nonetheless, there are core elements which are generally agreed upon as forming the cultural foundation of modern Europe.[47] One list of these elements given by K. Bochmann includes:[48]

- A common cultural and spiritual heritage derived from Greco-Roman antiquity, Christianity, the Renaissance and its Humanism, the political thinking of the Enlightenment, and the French Revolution, and the developments of Modernity, including all types of socialism;[49]

- A rich and dynamic material culture that has been extended to the other continents as the result of industrialization and colonialism during the "Great Divergence";[49]

- A specific conception of the individual expressed by the existence of, and respect for, a legality that guarantees human rights and the liberty of the individual;[49]

- A plurality of states with different political orders, which are condemned to live together in one way or another;[49]

- Respect for peoples, states and nations outside Europe.[49]

Berting says that these points fit with "Europe's most positive realisations".[50] The concept of European culture is generally linked to the classical definition of the Western world. In this definition, Western culture is the set of literary, scientific, political, artistic and philosophical principles which set it apart from other civilizations. Much of this set of traditions and knowledge is collected in the Western canon.[51] The term has come to apply to countries whose history has been strongly marked by European immigration or settlement during the 18th and 19th centuries, such as the Americas, and Australasia, and is not restricted to Europe.

Religion

Since the High Middle Ages, most of Europe used to be dominated by Christianity. There are three major denominations, Roman Catholic, Protestant and Eastern Orthodox, with Protestantism restricted mostly to Northern Europe, and Orthodoxy to Slavic regions, Romania, Greece and Georgia. Also The Armenian Apostolic Church, part of the Oriental Church, is in Europe - another branch of Christianity (world's oldest National Church). Catholicism, while typically centered in Western Europe, also has a very significant following in Central Europe (especially among the Germanic, Western Slavic and Hungarian peoples/regions) as well as in Ireland (with some in Great Britain).

Christianity has been the dominant religion shaping European culture for at least the last 1700 years.[52][53][54][55][56] Modern philosophical thought has very much been influenced by Christian philosophers such as St Thomas Aquinas and Erasmus. And throughout most of its history, Europe has been nearly equivalent to Christian culture,[57] The Christian culture was the predominant force in western civilization, guiding the course of philosophy, art, and science.[58][59] The notion of "Europe" and the "Western World" has been intimately connected with the concept of "Christianity and Christendom" many even attribute Christianity for being the link that created a unified European identity.[60]

Christianity is still the largest religion in Europe; according to a 2011 survey, 76.2% of Europeans considered themselves Christians.[61][62] Also according to a study on Religiosity in the European Union in 2012, by Eurobarometer, Christianity is the largest religion in the European Union, accounting for 72% of the EU's population.[63]

Islam has some tradition in the Balkans and the Caucasus due to conquest and colonization from the Ottoman Empire in the 16th to 19th centuries. Muslims account for the majority of the populations in Albania, Azerbaijan, Kosovo, Northern Cyprus (controlled by Turks), and Bosnia and Herzegovina. Significant minorities are present in the rest of Europe. Russia also has one of the largest Muslim communities in Europe, including the Tatars of the Middle Volga and multiple groups in the Caucasus, including Chechens, Avars, Ingush and others. With 20th-century migrations, Muslims in Western Europe have become a noticeable minority. According to the Pew Forum, the total number of Muslims in Europe in 2010 was about 44 million (6%),[64][64][64][65][64] while the total number of Muslims in the European Union in 2007 was about 16 million (3.2%).[66]

Judaism has a long history in Europe, but is a small minority religion, with France (1%) the only European country with a Jewish population in excess of 0.5%. The Jewish population of Europe is composed primarily of two groups, the Ashkenazi and the Sephardi. Ancestors of Ashkenazi Jews likely migrated to Central Europe at least as early as the 8th century, while Sephardi Jews established themselves in Spain and Portugal at least one thousand years before that. Jews originated in the Levant where they resided for thousands of years until the 2nd century AD, when they spread around the Mediterranean and into Europe, although small communities were known to exist in Greece as well as the Balkans since at least the 1st century BC. Jewish history was notably affected by the Holocaust and emigration (including Aliyah, as well as emigration to America) in the 20th century.

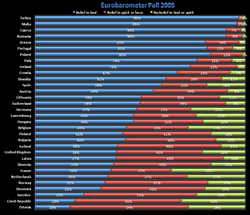

In modern times, significant secularization since the 20th century, notably in laicist France, Estonia and Czech Republic. Currently, distribution of theism in Europe is very heterogeneous, with more than 95% in Poland, and less than 20% in the Czech Republic and Estonia. The 2005 Eurobarometer poll[67] found that 52% of EU citizens believe in God.

Pan-European identity

"Pan-European identity" or "Europatriotism" is an emerging sense of personal identification with Europe, or the European Union as a result of the gradual process of European integration taking place over the last quarter of the 20th century, and especially in the period after the end of the Cold War, since the 1990s. The foundation of the OSCE following the 1990s Paris Charter has facilitated this process on a political level during the 1990s and 2000s.

From the later 20th century, 'Europe' has come to be widely used as a synonym for the European Union even though there are millions of people living on the European continent in non-EU member states. The prefix pan implies that the identity applies throughout Europe, and especially in an EU context, and 'pan-European' is often contrasted with national identity.[68]

European ethnic groups by sovereign state

Pan and Pfeil (2002) distinguish 33 peoples which form the majority population in at least one[lower-alpha 12] sovereign state geographically situated in Europe.[lower-alpha 13] These majorities range from nearly homogeneous populations as in Armenia and Poland, to comparatively slight majorities as in Latvia or Belgium, or even the marginal majority in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Montenegro is a multiethnic state in which no group forms a majority.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ethnic groups in Europe. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Maps of ethnic groups in Europe. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Europeans. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Aryan race

- European diaspora

- Caucasoid

- Central Asians

- Demography of Europe

- Emigration from Europe

- Ethnic groups in the Middle East

- Eurolinguistics

- Federal Union of European Nationalities

- Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities

- Genetic history of Europe

- Immigration to Europe

- Languages of Europe

- List of ethnic groups

- Nomadic peoples of Europe

- Peoples of the Caucasus

- White people

Notes

- ↑ Pan and Pfeil (2004) give 122 million for Europe and Asia taken together.

- ↑ Germans in Germany. Pan and Pfeil (2004) give 94 million for all German-speaking groups.

- ↑ Including french citizens in Belgium, Germany, Switzerland, Spain, UK and Italy.

- ↑ Pan and Pfeil (2004) give 55 million for the French-speaking groups, excluding the Occitans. Recensement officiel de l'Insee INSEE.fr give 65 million, to which the following French-speaking people must be added: 40% of the 11 million Belgians and 22.7% of the 8 million Swiss. 2 million regional languages speakers could be deducted, chiefly Alsatian (0.9 million), Occitan (0.8 million), Breton (0.2 million), Basque, Flemish and Catalan repreenting together less than 0.2 million speakers.

- ↑ Also known as Britons (Includes English, Scottish, Welsh, and Northern Irish people. Consists of 58 million British people in the United Kingdom and ca. 2 million British people resident in other countries in Europe.)

- ↑ Also Italian people in France, Germany, UK, Spain, Switzerland and other countries.

- ↑ Also Ukrainians in Russia, Poland and Belarus

- ↑ Also known as Spaniards (includes Catalans, Basques and Galicians). Pan and Pfeil give 31 million, excluding Catalans-Valencians-Balearics, Basques and Galicians population of 10 million, together about 41 million

- ↑ Polish diaspora, about 4.5 million Poles living in western Europe and about 1.5 million in eastern Europe.

- ↑ including Romanians in other countries

- ↑ including the Dutch-speaking inhabitants of Flanders

- ↑ Ethnic groups which form the majority in two states are the Romanians (in Romania and Moldova), and the Albanians (in Albania and the partly recognized Republic of Kosovo). Also to note is that Luxembourg has a common ethnonational group, the Luxembourgers of partial Germanic, Celtic and Latin (French) and transplanted Slavic origins. There are two official languages: French and German in the relatively small country, but the informal everyday language of its people is Letzeburgesch. Closely related groups holding majorities in separate states are German speakers (Germans, Austrians, Luxembourgers, Swiss German speakers), the various South Slavic ethnic groups in the states of former Yugoslavia, the Dutch/Flemish, the Russians/Belarusians, Czechs/Slovaks and the Bulgarians/Macedonians.

- ↑ Including the European portions of Russia, not including Turkey, Georgia and Kazakhstan, excluding microstates with fewer than 100,000 inhabitants: Andorra, Holy See, Liechtenstein, Monaco and San Marino.

- ↑ Percentages from the CIA Factbook unless indicated otherwise.

- 1 2 3 Transcontinental country, see boundaries of Europe.

- ↑ partially recognized state, see international recognition of Kosovo.

- 1 2 There is an ongoing controversy in Moldova over whether Moldovans' self-identification constitute a subgroup of Romanians or a separate ethnic group.

- ↑ There is no legal or generally accepted definitions of who is of Norwegian ethnicity in Norway. 87% of population have at least one parent who is born in Norway.

- ↑ In Norway, there is no clear legal definition of who is Sami. Therefore, exact numbers are not possible.

- ↑ Excluding Kosovo

- 1 2 Moldovans and Romanians were separately counted.

- ↑ Ethnicity group introduced with the ten-year United Kingdom census of 2011 by the Office for National Statistics, a non-ministerial department since 1 April 2008

- ↑ Since 2001 census in England and Wales, white residents could identify themselves as White Irish or White British though no separate White English or White Welsh options were offered. In Scotland, white residents could identify themselves as White Scottish or Other White British. In the census of Northern Ireland, White Irish and White British were combined into a single "White" ethnic group on the census forms.

References

- 1 2 Christoph Pan, Beate Sibylle Pfeil (2002), Minderheitenrechte in Europa. Handbuch der europäischen Volksgruppen, Braumüller, ISBN 3700314221 (Google Books, snippet view). Also 2006 reprint by Springer (Amazon, no preview) ISBN 3211353070. Archived December 5, 2015, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Pan and Pfeil (2004), "Problems with Terminology", pp. xvii-xx.

- ↑ "Population by Country of Birth and Nationality 2013: Table 2.1". Office for National Statistics. 28 August 2014. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- ↑ "15° Censimento generale della popolazione e delle abitazioni" (PDF) (in Italian). ISTAT. 27 April 2012. Retrieved 22 September 2012.

- ↑ see e.g. Genetic evidence for different male and female roles during cultural transitions in the British Isles doi:10.1073/pnas.071036898 PNAS 24 April 2001 Vol. 98 No. 9 5078–5083.

- ↑ Günther, Torsten; et al. (2015). "Ancient genomes link early farmers from Atapuerca in Spain to modern-day Basques" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 112 (38): 11917–11922. Bibcode:2015PNAS..11211917G. doi:10.1073/pnas.1509851112. PMC 4586848. PMID 26351665. Retrieved 2 November 2016.

- ↑ Massive migration from the steppe is a source for Indo-European languages in Europe, Haak et al, 2015

- ↑ Population genomics of Bronze Age Eurasia, Allentoft et al, 2015

- ↑ Eight thousand years of natural selection in Europe, Mathieson et al, 2015

- ↑ Richard, Lewis (2005). Finland, Cultural Lone Wolf. Intercultural Press. ISBN 978-1-931930-18-5. Niskanen, Markku (2002). "The Origin of the Baltic-Finns" (PDF). The Mankind Quarterly. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 October 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-06. Laitinen, Virpi; Päivi Lahermo (August 24, 2001). "Y-Chromosomal Diversity Suggests that Baltic Males Share Common Finno-Ugric-Speaking Forefathers" (PDF). Department of Genetics, University of Turku, Turku, Finnish Genome Center, University of Helsinki. Retrieved 2008-10-08.

- ↑

- ↑ Phillips, Fr Andrew. "The Last Christians Of North-West Africa: Some Lessons For Orthodox Today". Orthodoxengland.org.uk. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ↑ Hensel, Gottfried (12 December 2017). "Synopsis vniversæ philologiæ in qua miranda vnitas et harmonia lingvarvm: Totivs orbis terrarvm occvlta, e literarvm, syllabarvm, vocvmqve natvra & recessibvs eruitur ; cum grammatica ... mappisqve geographico-polyglottis ..." In commissis apvd heredes Homannianos. Retrieved 12 December 2017 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Karl Friedrich Vollgraff, Erster Versuch einer Begründung sowohl der allgemeinen Ethnologie durch die Anthropologie, wis auch der Staats und rechts-philosophie durch die Ethnologie oder Nationalität der Völker (1851), p. 257.

- ↑ A. Kumar, Encyclopaedia of Teaching of Geography (2002), p. 74 ff.; the tripartite subdivision of "Caucasians" into Nordic, Alpine and Mediterranean groups persisted among some scientists into the 1960s, notably in Carleton Coon's book The Origin of Races (1962).

- ↑ Andrew Barry, Political Machines (2001), p. 56

- ↑ Measuring European Population Stratification using Microarray Genotype Data, Sitesled.com Archived 2008-12-18 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "DNA heritage". Retrieved 2007-07-20.

- ↑ Dupanloup, Isabelle; Giorgio Bertorelle; Lounès Chikhi; Guido Barbujani. "Estimating the Impact of Prehistoric Admixture on the Genome of Europeans". Retrieved 2007-07-20.

- ↑ Tubb 1998, pp. 13–14

- ↑ Ann E. Killebrew, Biblical Peoples and Ethnicity. An Archaeological Study of Egyptians, Canaanites, Philistines and Early Israel 1300-1100 B.C.E. (Archaeology and Biblical Studies), Society of Biblical Literature, 2005

- ↑ Schama, Simon (18 March 2014). The Story of the Jews: Finding the Words 1000 BC-1492 AD. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-233944-7.

- ↑

- "In the broader sense of the term, a Jew is any person belonging to the worldwide group that constitutes, through descent or conversion, a continuation of the ancient Jewish people, who were themselves descendants of the Hebrews of the Old Testament."

- "The Jewish people as a whole, initially called Hebrews (ʿIvrim), were known as Israelites (Yisreʾelim) from the time of their entrance into the Holy Land to the end of the Babylonian Exile (538 BC)."

- ↑ "Israelite, in the broadest sense, a Jew, or a descendant of the Jewish patriarch Jacob" Israelite at Encyclopædia Britannica

- ↑ "Hebrew, any member of an ancient northern Semitic people that were the ancestors of the Jews." Hebrew (People) at Encyclopædia Britannica

- ↑ Ostrer, Harry (19 April 2012). Legacy: A Genetic History of the Jewish People. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 978-0-19-970205-3.

- ↑ Brenner, Michael (13 June 2010). A Short History of the Jews. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-14351-X.

- ↑ Scheindlin, Raymond P. (1998). A Short History of the Jewish People: From Legendary Times to Modern Statehood. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-513941-9.

- ↑ Adams, Hannah (1840). The History of the Jews: From the Destruction of Jerusalem to the Present Time. Sold at the London Society House and by Duncan and Malcom, and Wertheim.

- ↑ Diamond, Jared (1993). "Who are the Jews?" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 21, 2011. Retrieved November 8, 2010. Natural History 102:11 (November 1993): 12–19.

- ↑ Hammer, M. F; Redd, A. J; Wood, E. T; Bonner, M. R; Jarjanazi, H; Karafet, T; Santachiara-Benerecetti, S; Oppenheim, A; Jobling, M. A; Jenkins, T; Ostrer, H; Bonne-Tamir, B (2000). "Jewish and Middle Eastern non-Jewish populations share a common pool of Y-chromosome biallelic haplotypes". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 97 (12): 6769–6774. Bibcode:2000PNAS...97.6769H. doi:10.1073/pnas.100115997. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- ↑ Wade, Nicholas (9 May 2000). "Y Chromosome Bears Witness to Story of the Jewish Diaspora". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ↑ Archived 2014-10-11 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Costa, Marta D.; Pereira, Joana B.; Pala, Maria; Fernandes, Verónica; Olivieri, Anna; Achilli, Alessandro; Perego, Ugo A.; Rychkov, Sergei; Naumova, Oksana; Hatina, Jiři; Woodward, Scott R.; Eng, Ken Khong; Macaulay, Vincent; Carr, Martin; Soares, Pedro; Pereira, Luísa; Richards, Martin B. (8 October 2013). "A substantial prehistoric European ancestry amongst Ashkenazi maternal lineages". Nature Communications. 4: 2543. Bibcode:2013NatCo...4E2543C. doi:10.1038/ncomms3543. PMC 3806353. PMID 24104924. Retrieved 12 December 2017 – via www.nature.com.

- ↑ Lazaridis, Iosif; Patterson, Nick; Mittnik, Alissa; Renaud, Gabriel; Mallick, Swapan; Kirsanow, Karola; Sudmant, Peter H; Schraiber, Joshua G; Castellano, Sergi; Lipson, Mark; Berger, Bonnie; Economou, Christos; Bollongino, Ruth; Fu, Qiaomei; Bos, Kirsten I; Nordenfelt, Susanne; Li, Heng; Cesare de Filippo; Prüfer, Kay; Sawyer, Susanna; Posth, Cosimo; Haak, Wolfgang; Hallgren, Fredrik; Fornander, Elin; Rohland, Nadin; Delsate, Dominique; Francken, Michael; Guinet, Jean-Michel; Wahl, Joachim; et al. (2013). "Ancient human genomes suggest three ancestral populations for present-day Europeans". Nature. 513 (7518): 409. arXiv:1312.6639. Bibcode:2014Natur.513..409L. doi:10.1038/nature13673.

- ↑ Gregory Cochran, Henry Harpending, The 10,000 Year Explosion: How Civilization Accelerated Human Evolution, Basic Books, 2009 pp. 195–196.

- ↑ Moses ben Machir, in Seder Ha-Yom, p. 15a, Venice 1605 (Hebrew)

- ↑ Josephus Flavius, Antiquities, xi.v.2

- ↑ "Petition for expatriate voting officially launched". The Daily Star. 14 July 2012.

- ↑ "France's blacks stand up to be counted". Theglobeandmail.com. Archived from the original on 6 September 2008. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ↑ "Latin American Immigration to Southern Europe". Migrationinformation.org. 28 June 2007. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ↑ Born Abroad – Countries of birth, BBC News

- ↑ Kalaydjieva, L; Gresham, D; Calafell, F (2001). "Genetic studies of the Roma (Gypsies): a review". BMC Med. Genet. 2: 5. doi:10.1186/1471-2350-2-5. PMC 31389. PMID 11299048.

- ↑ ab Hisitione autem ortae sunt quattuor gentes Franci, Latini, Albani et Britti. ab Armenone autem quinque: Gothi, Valagothi, Gebidi, Burgundi, Longobardi. a Neguio vero quattuor Boguarii, Vandali, Saxones et Turingi. trans. J. A. Giles. London: Henry G. Bohn, 1848.

- ↑ Cf. Berting (2006:51).

- ↑ Cederman (2001:2) remarks: "Given the absence of an explicit legal definition and the plethora of competing identities, it is indeed hard to avoid the conclusion that Europe is an essentially contested concept." Cf. also Davies (1996:15); Berting (2006:51).

- ↑ Cf. Jordan-Bychkov (2008:13), Davies (1996:15), Berting (2006:51-56).

- ↑ K. Bochmann (1990) L'idée d'Europe jusqu'au XXè siècle, quoted in Berting (2006:52). Cf. Davies (1996:15): "No two lists of the main constituents of European civilization would ever coincide. But many items have always featured prominently: from the roots of the Christian world in Greece, Rome and Judaism to modern phenomena such as the Enlightenment, modernization, romanticism, nationalism, liberalism, imperialism, totalitarianism."

- 1 2 3 4 5 Berting 2006, p. 52

- ↑ Berting 2006, p. 51

- ↑ Duran (1995:81)

- ↑ Religions in Global Society - Page 146, Peter Beyer - 2006

- ↑ Cambridge University Historical Series, An Essay on Western Civilization in Its Economic Aspects, p.40: Hebraism, like Hellenism, has been an all-important factor in the development of Western Civilization; Judaism, as the precursor of Christianity, has indirectly had had much to do with shaping the ideals and morality of western nations since the christian era.

- ↑ Caltron J.H Hayas, Christianity and Western Civilization (1953), Stanford University Press, p.2: That certain distinctive features of our Western civilization — the civilization of western Europe and of America— have been shaped chiefly by Judaeo - Graeco - Christianity, Catholic and Protestant.

- ↑ Horst Hutter, University of New York, Shaping the Future: Nietzsche's New Regime of the Soul And Its Ascetic Practices (2004), p.111:three mighty founders of Western culture, namely Socrates, Jesus, and Plato.

- ↑ Fred Reinhard Dallmayr, Dialogue Among Civilizations: Some Exemplary Voices (2004), p.22: Western civilization is also sometimes described as "Christian" or "Judaeo- Christian" civilization.

- ↑ Dawson, Christopher; Glenn Olsen (1961). Crisis in Western Education (reprint ed.). p. 108. ISBN 978-0-8132-1683-6.

- ↑ Koch, Carl (1994). The Catholic Church: Journey, Wisdom, and Mission. Early Middle Ages: St. Mary's Press. ISBN 978-0-88489-298-4.

- ↑ Dawson, Christopher; Glenn Olsen (1961). Crisis in Western Education (reprint ed.). ISBN 978-0-8132-1683-6.

- ↑ Dawson, Christopher; Glenn Olsen (1961). Crisis in Western Education (reprint ed.). p. 108. ISBN 9780813216836.

- ↑ "Regional Distribution of Christians". Pewforum.org. 19 December 2011. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ↑ "Global Christianity: A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World's Christian Population" (PDF), Pew Research Center, 383, Pew Research Center, p. 130, 2011, retrieved 14 August 2013

- ↑ "Discrimination in the EU in 2012" (PDF), Special Eurobarometer, 383, European Union: European Commission, p. 233, 2012, archived from the original (PDF) on 2 December 2012, retrieved 14 August 2013

- 1 2 3 4 "The Future of the Global Muslim Population". Pewforum.org. 27 January 2011. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ↑ "Table: Muslim Population by Country". Pewforum.org. 27 January 2011. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ↑ "In Europa leben gegenwärtig knapp 53 Millionen Muslime" [Almost 53 million Muslims live in Europe at present]. Islam.de (in German). 8 May 2007. Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- ↑ EC.Europa.eu Archived May 24, 2006, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ This is particularly the case among proponents of the so-called confederalist or neo-functionalist position on European integration. Eder and Spohn (2005:3) note: "The evolutionary thesis of the making of a European identity often goes with the assumption of a simultaneous decline of national identities. This substitution thesis reiterates the well-known confederalist/neo-functionalist position in the debate on European integration, arguing for an increasing replacement of the nation-state by European institutions, against the intergovernmentalist/realist position, insisting on the continuing primacy of the nation-state."

- ↑ Demographics of Albania:Demographics of Albania

- ↑ Demographics of Albania

- ↑ The Greeks: the land and people since the war. James Pettifer. Penguin, 2000. ISBN 0-14-028899-6

- ↑ "CIA Factbook 2010". Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- ↑ Asatryan, Garnik; Arakelova, Victoria (Yerevan 2002). The Ethnic Minorities in Armenia. Part of the OSCE. Archived copy at WebCite (16 April 2010).

- ↑ Ministry of Culture of Armenia "The ethnic minorities in Armenia. Brief information". As per the most recent census in 2011. "National minority".

- ↑ "Kommission für Migrations und Integrationsforschung der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften" (PDF). Statistik Austria. 2012. p. 27. (total population to calculate percentages with is on page 23)

- ↑ Population and housing census in the Republic of Bulgaria 2011

- ↑ "Population at the first day of the quarter by municipality, sex, age, marital status, ancestry, country of origin and citizenship". Statistics Denmark. Retrieved 13 February 2017. January 2017

- ↑ "POPULATION BY SEX, ETHNIC NATIONALITY AND COUNTY, 1 JANUARY. ADMINISTRATIVE DIVISION". stat.ee.

- ↑ Project, Joshua. "French in France". Joshuaproject.net. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ↑ "France". State.gov. 2012-02-15. Retrieved 2012-08-13.

- ↑ "Immigration is hardly a recent development in French history, as Gérard Noiriel amply demonstrates in his history of French immigration, The French Melting Pot. Noiriel estimates that one third of the population currently living in France is of "foreign" descent", Marie-Christine Weidmann-Koop, "France at the dawn of the twenty-first century, trends and transformations", Summa Publications, Inc., 2000, P.160

- ↑ " In present day France, one-third of the population has grandparents that were born outside France", Jean-Benoît Nadeau and Julie Barlow, "Sixty Million Frenchmen Can't be Wrong: What makes the French so French", Robson Books Ltd, 2004, p.8

- ↑ "2016" (PDF). Statistisches Bundesamt (Destatis), 2017. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- ↑ "MRG Directroy:Greece". Greece Overview. MRG. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ↑ "Population by country of citizenship, sex and age 1 January 1998–2016". Reykjavík, Iceland: Statistics Iceland. Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- ↑ "CSO Census 2016 Chapter 6 - Ethnicity and Irish Travellers" (PDF). Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- ↑ "Bilancio demografico nazionale".

- ↑ "Численность населения Республики Казахстан по отдельным этносам на начало 2016 года". Archived from the original on 14 October 2017. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- ↑ Social Statistics Department of Latvia. "Latvijas iedzīvotāju etniskais sastāvs" (PDF). Social Statistics Department of Latvia. Retrieved 21 June 2015.

- ↑ "Lietuvos gyventojų tautinė sudėtis 2014–2015 m". Alkas.lt. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

- ↑ Census 2011. National Statistics Office, Malta

- ↑ Official CBS website containing all Dutch demographic statistics. Cbs.nl. Retrieved on 4 July 2017.

- ↑ Personer med innvandringsbakgrunn, etter innvandringskategori, landbakgrunn og kjønn. 1. januar 2012 ( Archived September 18, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. SSB (Statistics Norway), Retrieved November 6, 2012

- ↑ Struktura narodowo-etniczna, językowa i wyznaniowa ludności Polski. Narodowy Spis Powszechny Ludności i Mieszkań 2011 [National-ethnic, linguistic and religious structure of Poland. National Census of Population and Housing 2011 (PDF) (in Polish). Central Statistical Office. November 2015. ISBN 978-83-7027-597-6.]

- ↑ Ludność. Stan i struktura demograficzno-społeczna. Narodowy Spis Powszechny Ludności i Mieszkań 2011 [Population. Number and demographical-social structure. National Census of Population and Housing 2011 (PDF) (in Polish). Central Statistical Office. February 2013. ISBN 978-83-7027-521-1.]

- ↑ Rykała, Andrzej (2014). "National and Ethnic Minorities in Poland from the Perspective of Political Geography". Acta Universitatis Lodziensis. Folia Geographica Socio-Oeconomica (in Polish). 17: 63–111 – via CEON Biblioteka Nauki.

- ↑ Официальный сайт Всероссийской переписи населения 2010 года. Информационные материалы об окончательных итогах Всероссийской переписи населения 2010 года Archived October 6, 2014, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Всероссийская перепись населения 2010. Национальный состав населения РФ 2010". Gks.ru. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ↑ "SCB.se". Scb.se. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ↑ "SCB.se". Scb.se. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ↑ "Middle East :: TURKEY". CIA The World Factbook.

Bibliography

- Andrews, Peter A.; Benninghaus, Rüdiger (2002), Ethnic Groups in the Republic of Turkey, Reichert, ISBN 3-89500-325-5

- Banks, Marcus (1996), Ethnicity: Anthropological Constructions, Routledge

- Berting, J. (2006), Europe: A Heritage, a Challenge, a Promise, Eburon Academic Publishers, ISBN 90-5972-120-9

- Cederman, Lars-Erik (2001), "Political Boundaries and Identity Trade-Offs", in Cederman, Lars-Erik, Constructing Europe's Identity: The External Dimension, London: Lynne Rienner Publishers, pp. 1–34

- Cole, J. W.; Wolf, E. R. (1999), The Hidden Frontier: Ecology and Ethnicity in an Alpine Valley, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-21681-5

- Davies, N. (1996), Europe: A History, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-820171-0

- Dow, R. R.; Bockhorn, O. (2004), The Study of European Ethnology in Austria, Progress in European Ethnology, Ashgate Publishing, ISBN 978-0-7546-1747-1

- Eberhardt, Piotr; Owsinski, Jan (2003), Ethnic Groups and Population Changes in Twentieth-century Central Eastern Europe, M.E. Sharpe, ISBN 0-7656-0665-8

- Eder, Klaus; Spohn, Willfried (2005). Collective Memory and European Identity: The Effects of Integration and Enlargement. Burlington: Ashgate Publishing Company. ISBN 0-7546-4401-4.

- Gresham, D.; et al. (2001), "Origins and divergence of the Roma (Gypsies)", American Journal of Human Genetics, 69 (6): 1314–1331, doi:10.1086/324681, PMC 1235543, PMID 11704928 Online article

- Karolewski, Ireneusz Pawel; Kaina, Viktoria (2006), European Identity: Theoretical Perspectives and Empirical Insights, LIT Verlag, ISBN 3-8258-9288-3

- Jordan-Bychkov, T.; Bychkova-Jordan, B. (2008), The European Culture Area: A Systematic Geography. Maryland, Rowman & Littlefield, ISBN 0-7425-1628-8

- Latham, Robert Gordon (1854), The Native Races of the Russian Empire, Hippolyte Baillière (London) Full text on google books

- Laitin, David D. (2000), Culture and National Identity: "the East" and European Integration, Robert Schuman Centre

- Gross, Manfred (2004), Romansh: Facts & Figures, Lia Rumantscha, ISBN 3-03900-037-3 Online version

- Levinson, David (1998), Ethnic Groups Worldwide: A Ready Reference Handbook, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 978-1-57356-019-1 part I: Europe, pp. 1–100.

- Hobsbawm, E. J.; Kertzer, David J. (1992), "Ethnicity and Nationalism in Europe Today", Anthropology Today, 8: 3–8, doi:10.2307/3032805, JSTOR 3032805

- Minahan, James (2000), One Europe, many nations: a historical dictionary of European national groups, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 0-313-30984-1

- Panikos Panayi, Outsiders: A History of European Minorities (London: Hambledon Press, 1999)

- Olson, James Stuart; Pappas, Lee Brigance; Pappas, Nicholas Charles (1994), An Ethnohistorical Dictionary of the Russian and Soviet Empire, Greenwood, ISBN 0-313-27497-5

- O'Néill, Diarmuid (2005), Rebuilding the Celtic languages: reversing language shift in the Celtic countries, Y Lolfa, ISBN 0-86243-723-7

- Panayi, Panikos (1999), An Ethnic History of Europe Since 1945: Nations, States and Minorities, Longman, ISBN 0-582-38135-5

- Parman, S. (ed.) (1998), Europe in the Anthropological Imagination, Prentice Hall

- Stephens, Meic (1976), Linguistic Minorities in Western Europe, Gomer Press, ISBN 0-608-18759-3

- Szaló, Csaba (1998), On European Identity: Nationalism, Culture & History, Masaryk University, ISBN 80-210-1839-9

- Stone, Gerald (1972), The Smallest Slavonic Nation: The Sorbs of Lusatia, Athlene Press, ISBN 0-485-11129-2

- Tubb, Jonathan N. (1998). Canaanites. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-3108-X.

- Vembulu, R. Pavananthi (2003), Understanding European Integration: History, Culture, and Politics of Identity, Aakar Books, ISBN 81-87879-10-6