Genetic history of Europe

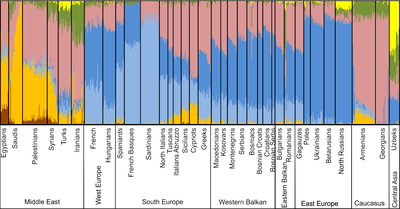

South/West European North/East European Caucasian

Middle Eastern South Asian East Asian Sub-Saharan African[1]

The genetic history of Europe since the Upper Paleolithic is inseparable from that of wider Western Eurasia. By about 50,000 years ago (50 ka) a basal West Eurasian lineage had emerged (alongside a separate East Asian lineage) out of the undifferentiated "non-African" lineage of 70 ka.[3] The basal Western Eurasians were early exposed to significant Neanderthal admixture. Introgression of Neanderthal traits persisted in European populations into the present, affecting traits such as skin tone and hair color, height, sleeping patterns and mood.[4]

European early modern humans (EEMH) lineages between 40 to 26 ka (Aurignacian) were still part of a large Western Eurasian "meta-population", related to Central and Western Asian populations.[3] Divergence into genetically distinct sub-populations within Western Eurasia is a result of increased selection pressure and founder effects during the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM, Gravettian).[5] By the end of the LGM, after 20 ka, A Western European lineage, dubbed West European Hunter-Gatherer (WHG) emerges from the Solutrean refugium during the European Mesolithic.[6] These mesolithic hunter-gatherer cultures are substantially replaced in the Neolithic Revolution by the arrival of Early European Farmers (EEF) lineages derived from mesolithic populations of West Asia (Anatolia and the Caucasus).[7] In the European Bronze Age, there were again substantial population replacements in parts of Europe by the intrusion of Ancient North Eurasian (ANE) lineages from the Central Asian steppes. These population replacements are associated with the Beaker culture archaeologically and with the Indo-European expansion linguistically.[8]

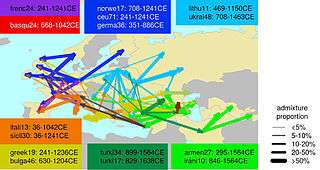

As a result of the population movements during the Mesolithic to Bronze Age, modern European populations are distinguished by their clinal differences in WHG, EEF and ANE ancestry.[9] Admixture rates varied geographically; in the late Neolithic, WHG ancestry in farmers in Hungary was at around 10%, in Germany around 25% and in Iberia as high as 50%.[10] Sardinians are characterized by almost pure derivation from EEF. The contribution of EEF is strongest in Mediterranean Europe, and declines towards northern and northeastern Europe, where WHG ancestry is stronger. ANE ancestry is found through throughout Europe, with maxima of about 20% found in Baltic people and Finns. WHG ancestry is also strongest in northeatern Europe, with contributions close to 50% found in the Baltic.[11] Ethnogenesis of the modern ethnic groups of Europe in the historical period is associated with numerous admixture events, primiarily those associated with the Roman Empire, and the Germanic and Norse, Slavic, Arab and Turkish expansions.

Research into the genetic history of Europe became possible in the second half of the 20th century, but did not yield results with high resolution before the 1990s. In the 1990s, preliminary results became possible, but they remained mostly limited to studies of mitochondrial and Y-chromosomal lineages. Autosomal DNA became more easily accessible in the 2000s, and since the mid-2010s, results of previously unattainable resolution, many of them based on full-genome analysis of ancient DNA, have been published at an accelerated pace.[12][12][13]

Prehistory

The prehistory of the European peoples can be traced by the examination of archaeological sites, linguistic studies and by the examination of the DNA of the people who live in Europe or from ancient DNA. The research continues and so theories rise and fall. Although it is possible to track migrations of people across Europe using founder analysis of DNA, most information on these movements comes from archaeology.[14]

It is important to note that the settlement of Europe did not occur in discrete migrations, as might appear to be suggested. Rather, the settlement process was complex and "likely to have occurred in multiple (sic) waves from the east and to have been subsequently obscured by millennia of recurrent gene flow".[14]

Due to natural selection, the percentage of Neanderthal DNA in ancient Europeans gradually decreased over time. From 45,000 BP to 7,000 BP, the percentage dropped from around 3–6% to 2%.[13] The removal of Neanderthal-derived alleles occurred more frequently around genes than other parts of the genome.[13]

Palaeolithic

Neanderthals inhabited much of Europe and western Asia from as far back as 130,000 years ago. They existed in Europe as late as 30,000 years ago. They were eventually replaced by anatomically modern humans (AMH; sometimes known as Cro-Magnons), who began to appear in Europe circa 40,000 years ago. Given that the two hominid species likely coexisted in Europe, anthropologists have long wondered whether the two interacted.[16] The question was resolved only in 2010, when it was established that Eurasian populations exhibit Neanderthal admixture, estimated at 1.5–2.1% on average.[17] The question now became whether this admixture had taken place in Europe, or rather in the Levant, prior to AMH. migration into Europe.

There has also been speculation about the inheritance of specific genes from Neanderthals. For example, one MAPT locus 17q21.3 which is split into deep genetic lineages H1 and H2. Since the H2 lineage seems restricted to European populations, several authors had argued for inheritance from Neanderthals beginning in 2005.[18][19][20][21][22] However the preliminary results from the sequencing of the full Neanderthal Genome at that time (2009), failed to uncover evidence of interbreeding between Neanderthals and modern humans.[23][24] By 2010, findings by Svante Pääbo (Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology at Leipzig, Germany), Richard E. Green (University of California, Santa Cruz), and David Reich (Harvard Medical School), comparing the genetic material from the bones of three Neanderthals with that from five modern humans, did show a relationship between Neanderthals and modern people outside Africa.

It is thought that modern humans began to inhabit Europe during the Upper Paleolithic about 40,000 years ago. Some evidence shows the spread of the Aurignacian culture.[25]

From a purely patrilineal, Y-chromosome perspective, it is possible that the old haplogroups C, F and/or E may be those with the oldest presence in Europe. They have been found in some very old human remains in Europe. However, other haplogroup are far more common among living European males.

Haplogroup I (M170), which is now relatively common and widespread within Europe, may represent a Palaeolithic marker – its age has been estimated at ~ 22,000 BP. While it is now concentrated in Europe, it probably arose in a male from the Middle East or Caucasus, or their near descendants, c. 20–25,000 years BP, when it diverged from its immediate ancestor, haplogroup IJ. At about this time, an Upper Palaeolithic culture also appeared, known as the Gravettian.[26]

Earlier research into Y-DNA had instead focused on haplogroup R1 (M173): the most populous lineage among living European males; R1 was also believed to have emerged ~ 40,000 BP in Central Asia.[27][28] However, it is now estimated that R1 emerged substantially more recently: a 2008 study dated the most recent common ancestor of haplogroup IJ to 38,500 and haplogroup R1 to 18,000 BP. This suggested that haplogroup IJ colonists formed the first wave and haplogroup R1 arrived much later.[29]

Thus the genetic data suggests that, at least from the perspective of patrilineal ancestry, separate groups of modern humans took two routes into Europe: from the Middle East via the Balkans and another from Central Asia via the Eurasian Steppe, to the north of the Black Sea.

Martin Richards et al. found that 15–40% of extant mtDNA lineages trace back to the Palaeolithic migrations (depending on whether one allows for multiple founder events).[30] MtDNA haplogroup U5, dated to be ~ 40–50 kYa, arrived during the first early upper Palaeolithic colonisation. Individually, it accounts for 5–15% of total mtDNA lineages. Middle U.P. movements are marked by the haplogroups HV, I and U4. HV split into Pre-V (around 26,000 years old) and the larger branch H, both of which spread over Europe, possibly via Gravettian contacts.[26][31]

Haplogroup H accounts for about half the gene lines in Europe, with many subgroups. The above mtDNA lineages or their precursors, are most likely to have arrived into Europe via the Middle East. This contrasts with Y DNA evidence, whereby some 50%-plus of male lineages are characterised by the R1 superfamily, which is of possible central Asian origin. Ornella Semino postulates that these differences "may be due in part to the apparent more recent molecular age of Y chromosomes relative to other loci, suggesting more rapid replacement of previous Y chromosomes. Gender-based differential migratory demographic behaviors will also influence the observed patterns of mtDNA and Y variation".

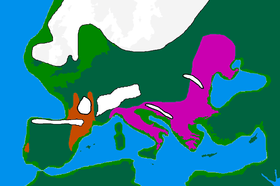

Last Glacial Maximum

The Last Glacial Maximum ("LGM") started c. 30 ka BC, at the end of MIS 3, leading to a depopulation of Northern Europe. According to the classical model, people took refuge in climatic sanctuaries (or refugia) as follows:

- Northern Iberia and Southwest France, together making up the "Franco-Cantabrian" refugium

- The Balkans

- Ukraine and more generally the northern coast of the Black Sea[26]

- Italy.[32]

This event decreased the overall genetic diversity in Europe, a "result of drift, consistent with an inferred population bottleneck during the Last Glacial Maximum".[33] As the glaciers receded from about 16,000–13,000 years ago, Europe began to be slowly repopulated by people from refugia, leaving genetic signatures.[34]

Some Y haplogroup I clades appear to have diverged from their parental haplogroups sometime during or shortly after the LGM.[35] Haplogroup I2 is prevalent in the western Balkans, as well as the rest of southeastern and central-eastern Europe in more moderate frequencies. Its frequency drops rapidly in central Europe, suggesting that the survivors bearing I2 lineages expanded predominantly through south-eastern and central-eastern Europe.[36]

Cinnioglu sees evidence for the existence of an Anatolian refuge, which also harboured Hg R1b1b2.[37] Today, R1b dominates the y chromosome landscape of western Europe, including the British Isles, suggesting that there could have been large population composition changes based on migrations after the LGM.

Semino, Passarino and Pericic place the origins of haplogroup R1a within the Ukrainian ice-age refuge. Its current distribution in eastern Europe and parts of Scandinavia are in part reflective of a re-peopling of Europe from the southern Russian/Ukrainian steppes after the Late Glacial Maximum.[38][39][40]

From an mtDNA perspective, Richards et al. found that the majority of mtDNA diversity in Europe is accounted for by post-glacial re-expansions during the late upper Palaeolithic/ Mesolithic. "The regional analyses lend some support to the suggestion that much of western and central Europe was repopulated largely from the southwest when the climate improved. The lineages involved include much of the most common haplogroup, H, as well as much of K, T, W, and X." The study could not determine whether there were new migrations of mtDNA lineages from the near east during this period; a significant input was deemed unlikely.[14]

The alternative model of more refugees was discussed by Bilton et al.[41]

From a study of 51 individuals, researchers were able to identify five separate genetic clusters of ancient Europeans during the LGM: the Věstonice Cluster (34,000–26,000 years ago), associated with the Gravettian culture; the Mal'ta Cluster (24,000–17,000), associated with the Mal'ta-Buret' culture, the El Mirón Cluster (19,000–14,000 years ago), associated with the Magdalenian culture; the Villabruna Cluster (14,000–7,000 years ago) and the Satsurblia Cluster (13,000 to 10,000 years ago), Caucasus hunter-gatherers.[13]

From around 37,000 years ago, all ancient Europeans began to share some ancestry with modern Europeans.[13] This founding population is represented by GoyetQ116-1, a 35,000 year old specimen from Belgium.[13] This lineage disappears from the record and is not found again until 19,000 BP in Spain at El Mirón, which shows strong affinities to GoyetQ116-1.[13] During this interval, the distinct Věstonice Cluster is predominant in Europe, even at Goyet.[13] The re-expansion of the El Mirón Cluster coincided with warming temperatures following the retreat of the glaciers during the Last Glacial Maximum.[13] From 37,000 to 14,000 years ago, the population of Europe consisted of an isolated population descended from a founding population that didn't interbreed significantly with other populations.[42]

Mesolithic

Mesolithic (post-LGM) populations had diverged significantly due to their relative isolation over several millennia, due to the harsh selection pressures during the LGM, and due to the founder effects caused by the rapid expansion from LGM refugia in the beginning Mesolithic.[5] By the end of the LGM, around 19 to 11 ka, the familiar varieties of Eurasian phenotypes had emerged. However, the lineage of Mesolithic hunter-gatherers of Western Europe (WHG) does not survive as a majority contribution in any modern population. They were most likely blue eyed, and retained the dark skin pigmentation of pre-LGM EEMH.[43] The HERC2 and OCA2 variations for blue eyes are derived from the WHG lineage were also found in the Yamna people.[43]

Around 14,000 years ago, the Villabruna Cluster shifted away from GoyetQ116-1 affinity and started to show more affinity with the Near East, a shift which coincided with the warming temperatures of the Bølling-Allerød interstadial.[13] This genetic shift shows that Near East populations had probably already begun moving into Europe during the end of the Upper Paleolithic, about 6,000 years earlier than previously thought, before the introduction of farming.[42] A few specimens from the Villabruna Cluster also show genetic affinities for East Asians that are derived from gene flow.[13][42] The HERC2 variation for blue eyes first appears around 13,000 to 14,000 years ago in Italy and the Caucasus.[13] The light skin pigmentation characteristic of modern Europeans is estimated to have spread across Europe in a "selective sweep" during the Mesolithic (19 to 11 ka). The associated TYRP1 SLC24A5 and SLC45A2 alleles emerge around 19 ka, still during the LGM, most likely in the Caucasus. [44]

Neolithic

A big cline in genetic variation that has long been recognised in Europe seems to show important dispersals from the direction of the Middle East. This has often been linked to the spread of farming technology during the Neolithic, which has been argued to be one of the most important periods in determining modern European genetic diversity.

The Neolithic started with the introduction of farming, beginning in SE Europe approximately 10,000–3000 BC, and extending into NW Europe between 4500–1700 BC. During this era, the Neolithic revolution led to drastic economic as well as socio-cultural changes in Europe and this is also thought to have had a big effect on Europe's genetic diversity, especially concerning genetic lineages entering Europe from the Middle East into the Balkans. There were several phases of this period:

- In a late European Mesolithic prelude to the Neolithic, it appears that Near Eastern peoples from areas that already had farming, and who also had sea-faring technology, had a transient presence in Greece, for example at Franchthi Cave.[45][46]

- There is consensus that agricultural technology and the main breeds of animals and plants which are farmed entered Europe from somewhere in the area of the Fertile Crescent and specifically the Levant region from the Sinai to Southern Anatolia[47][48] (Less certainly, this agricultural revolution is sometimes argued to have in turn been partly triggered by movements of people and technology coming across the Sinai from Africa.)

- A later stage of the Neolithic, the so-called Pottery Neolithic, saw an introduction of pottery into the Levant, Balkans and Southern Italy (it had been present in the area of modern Sudan for some time before it is found in the Eastern Mediterranean but it is thought to have developed independently) and this may have also been a period of cultural transfer from the Levant into the Balkans.

An important issue regarding the genetic impact of neolithic technologies in Europe is the manner by which they were transferred into Europe; whether farming was introduced by a significant migration of farmers from the Near East (Cavalli-Sforza's biological demic diffusion model) or a "cultural diffusion" or a combination of the two. Secondarily, population geneticists have tried to clarify whether any genetic signatures of Near Eastern origin correspond to the expansion routes postulated by the archaeological evidence.[49]

Martin Richards estimated that only 11% of European mtDNA is due to immigration in this period, suggesting that farming was spread primarily due to being adopted by indigenous Mesolithic populations, rather than due to immigration from Near East. Gene flow from SE to NW Europe seems to have continued in the Neolithic, the percentage significantly declining towards the British Isles. Classical genetics also suggested that the largest admixture to the European Paleolithic/Mesolithic stock was due to the Neolithic revolution of the 7th to 5th millennia BC.[50] Three main mtDNA gene groups have been identified as contributing Neolithic entrants into Europe: J, T1 and U3 (in that order of importance). With others, they amount up to around 20% of the gene pool.[30]

In 2000, Semino's study on Y DNA revealed the presence of haplotypes belonging to the large clade E1b1b1 (E-M35). These were predominantly found in the southern Balkans, southern Italy and parts of Iberia. Semino connected this pattern, along with J haplogroup subclades, to be the Y-DNA component of Cavalli-Sforza's Neolithic demic-diffusion of farmers from the Near East.[51] Rosser et al. rather saw it as a (direct) 'North African component' in European genealogy, although they did not propose a timing and mechanism to account for it.[52] Underhill and Kivisild (2007) also described E1b1b as representing a late-Pleistocene migration from Africa to Europe over the Sinai Peninsula in Egypt, evidence for which does not show up in mitochondrial DNA.[53]

Concerning timing the distribution and diversity of V13 however, Battaglia et al. (2008) proposed an earlier movement whereby the E-M78* lineage ancestral to all modern E-V13 men moved rapidly out of a Southern Egyptian homeland and arrived in Europe with only Mesolithic technologies. They then suggest that the E-V13 sub-clade of E-M78 only expanded subsequently as native Balkan 'foragers-cum-farmers' adopted Neolithic technologies from the Near East. They propose that the first major dispersal of E-V13 from the Balkans may have been in the direction of the Adriatic Sea with the Neolithic Impressed Ware culture often referred to as Impressa or Cardial. Peričic et al. (2005), rather propose that the main route of E-V13 spread was along the Vardar-Morava-Danube river 'highway' system.

In contrast to Battaglia, Cruciani et al. (2007) tentatively suggested (i) a different point where the V13 mutation happened on its way from Egypt to the Balkans via the Middle East, and (ii) a later dispersal time. The authors proposed that the V13 mutation first appeared in western Asia, where it is found in low but significant frequencies, whence it entered the Balkans sometime after 11 kYa. It later experienced a rapid dispersal which he dated to c. 5300 years ago in Europe, coinciding with the Balkan Bronze Age. Like Peričic et al. they consider that "the dispersion of the E-V13 and J-M12 haplogroups seems to have mainly followed the river waterways connecting the southern Balkans to north-central Europe".

More recently, Lacan et al. (2011) announced that a 7000-year-old skeleton in a Neolithic context in a Spanish funeral cave, was an E-V13 man. (The other specimens tested from the same site were in haplogroup G2a, which has been found in Neolithic contexts throughout Europe.) Using 7 STR markers, this specimen was identified as being similar to modern individuals tested in Albania, Bosnia, Greece, Corsica, and Provence. The authors therefore proposed that, whether or not the modern distribution of E-V13 of today is a result of more recent events, E-V13 was already in Europe within the Neolithic, carried by early farmers from the Eastern Mediterranean to the Western Mediterranean, much earlier than the Bronze age. This supports the proposals of Battaglia et al. rather than Cruciani et al. at least concerning earliest European dispersals, but E-V13 may have dispersed more than once. Even more recent than the Bronze Age, it has also been proposed that modern E-V13's modern distribution in Europe is at least partly caused by Roman era movements of people.[54] (See below.)

After an initial focus upon E1b1b as a Neolithic marker, a more recent study in January 2010, looked at Y haplogroup R1b1b, which is much more common in Western Europe. Mark Jobling said: "We focused on the commonest Y-chromosome lineage in Europe, carried by about 110 million men, it follows a gradient from south-east to north-west, reaching almost 100% frequency in Ireland. We looked at how the lineage is distributed, how diverse it is in different parts of Europe, and how old it is." The results suggested that the lineage R1b1b2 (R-M269), like E1b1b or J lineages, spread together with farming from the Near East. Dr Patricia Balaresque added: "In total, this means that more than 80% of European Y chromosomes descend from incoming farmers. In contrast, most maternal genetic lineages seem to descend from hunter-gatherers. To us, this suggests a reproductive advantage for farming males over indigenous hunter-gatherer males during the switch from hunting and gathering, to farming".[55][56][57][58]

A more recent article concerning R1b made the counter claim that "the data are still controversial and the analyses so far performed are prone to a number of biases" and propose that the data are best explained by "an earlier, pre-Neolithic dispersal of haplogroups from a common ancestral gene pool".[59]

The migration of Neolithic farmers into Europe brought along several new adaptations.[43] The variation for light skin colour was introduced to Europe by the neolithic farmers.[43] After the arrival of the neolithic farmers, a SLC22A4 mutation was selected for, a mutation which probably arose to deal with ergothioneine deficiency but increases the risk of ulcerative colitis, coeliac disease, and irritable bowel syndrome.

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age saw the development of long-distance trading networks, particularly along the Atlantic Coast and in the Danube valley. There was migration from Norway to Orkney and Shetland in this period (and to a lesser extent to mainland Scotland and Ireland). There was also migration from Germany to eastern England. Martin Richards estimated that there was about 4% mtDNA immigration to Europe in the Bronze Age.

Another theory about the origin of the Indo-European language centres around a hypothetical Proto-Indo-European people, who traced in the Kurgan hypothesis, to north of the Black and Caspian Seas at about 4500 BC.[60] They domesticated the horse and possibly invented the wheel, and are considered to have spread their culture and genes across Europe.[61] The Y haplogroup R1a is a proposed marker of these "Kurgan" genes, as is the Y Haplogroup R1b, although these haplogroups as a whole may be much older than the language family.[62]

In the far north, carriers of the Y-haplogroup N arrived to Europe from Siberia, eventually expanding as far as Finland, though the specific timing of their arrival is uncertain. The most common North European subclade N1c1 is estimated to be around 8,000 years old. There is evidence of human settlement in Finland dating back to 8500 BCE, linked with Kunda culture and its putative ancestor Swiderian culture, but the latter is thought to have European origin. The geographical spread of haplogroup N in Europe is well aligned with the Pit–Comb Ware culture, whose emergence is commonly dated c. 4200 BCE, and with the distribution of Uralic languages. Mitochondrial DNA studies of Sami people, Haplogroup U5 are consistent with multiple migrations to Scandinavia from Volga-Ural region, starting 6,000 to 7,000 years before present.[63]

The relationship between roles of European and Asian colonists in the prehistory of Finland is a point of some contention, and some scholars insist that Finns are "predominantly Eastern European and made up of people who trekked north from the Ukrainian refuge during the Ice Age".[64] Farther east, the issue is less contentious. Haplogroup N carriers account for a significant part of all non-Slavic ethnic groups in northern Russia, including 37% of Karelians, 35% of Komi people (65% according to another study[65]), 67% of Mari people, as many as 98% of Nenets people, 94% of Nganasans, and 86% to 94% of Yakuts.[66]

The Yamna may have brought Indo-European languages with them. The Yamna altered the gene pools of northern and central Europe; some populations such as Norwegians, owe around 50% of their ancestry to this group.[67][68]

The Yamna component contains partial ancestry from an Ancient North Eurasian component first identified in Mal'ta.[69] According to Iosif Lazaridis, "the Ancient North Eurasian ancestry is proportionally the smallest component everywhere in Europe, never more than 20 percent, but we find it in nearly every European group we’ve studied."[70] This genetic component does not come directly from the Mal'ta lineage itself, but a related lineage that separated from the Mal'ta lineage.[13]

Half of the Yamna component is derived from a Caucasus hunter-gatherer strand (Satsurblia).[69] On November 16, 2015, in a study published in the journal Nature Communications,[69] geneticists announced that they had found a new fourth ancestral "tribe" or "strand" which had contributed to the modern European gene pool. They analysed genomes from two hunter-gatherers from Georgia which were 13,300 and 9,700 years old, and found that these Caucasus hunter-gatherers were probably the source of the farmer-like DNA in the Yamna. According to co-author Dr Andrea Manica of the University of Cambridge: "The question of where the Yamnaya come from has been something of a mystery up to now....we can now answer that as we've found that their genetic make-up is a mix of Eastern European hunter-gatherers and a population from this pocket of Caucasus hunter-gatherers who weathered much of the last Ice Age in apparent isolation."[67]

According to Lazaridis et al. (2016), a population related to the people of the Chalcolithic Iran contributed to roughly half of the ancestry of Yamna populations of the Pontic–Caspian steppe. These Iranian Chalcolithic people were a mixture of "the Neolithic people of western Iran, the Levant, and Caucasus Hunter Gatherers."[71]

The genetic variations for lactase persistence and greater height came with the Yamna people.[43] The derived allele of the KITLG gene (SNP rs12821256) that is associated with – and likely causal for – blond hair in Europeans is found in populations with Eastern but not Western Hunter-Gatherers ancestry, suggesting that its origin is in the Ancient North Eurasian (ANE) population and may have been spread in Europe by individuals with Steppe ancestry. Consistent with this, the earliest known individual with the derived allele is a ANE individual from the Late Upper Paleolithic Afontova Gora archaeological complex.[72]

Recent history

During the period of the Roman Empire, historical sources show that there were many movements of people around Europe, both within and outside the Empire. Historic sources sometimes cite instances of genocide inflicted by the Romans upon rebellious provincial tribes. If this did in fact occur, it would have been limited given that modern populations show considerable genetic continuity in their respective regions. The process of 'Romanisation' appears to have been accomplished by the colonisation of provinces by a few Latin speaking administrators, military personnel, settled veterans, and private citizens (merchants, traders) who emanated from the Empire's various regions (and not merely from Roman Italy). They served as a nucleus for the acculturation of local notables.[74]

Given their small numbers and varied origins, Romanization does not appear to have left distinct genetic signatures in Europe. Indeed, Romance-speaking populations in the Balkans, like Romanians, Aromanians, Moldovans, etc. have been found to genetically resemble neighbouring Greek and South Slavic-speaking peoples rather than modern Italians, proving that they were genetically speaking, mainly through I2a2 M-423 and E1b1b1, V-13 Haplogroups native to this area.[75][76]

Steven Bird has speculated that E1b1b1a was spread during the Roman era through Thracian and Dacian populations from the Balkans into the rest of Europe.[54]

Concerning the late Roman period of (not only) Germanic "Völkerwanderung", some suggestions have been made, at least for Britain, with Y haplogroup I1a being associated with Anglo-Saxon immigration in eastern England, and R1a being associated with Norse immigration in northern Scotland.[77]

Population genetics

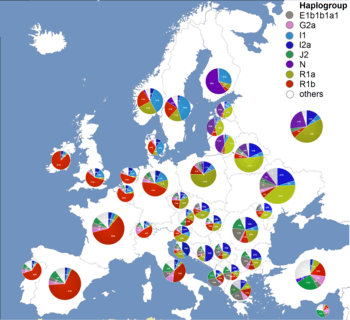

Patrilineal studies

There are four main Y-chromosome DNA haplogroups that account for most of Europe's patrilineal descent.[78]

- Haplogroup I is found in the form of various sub-clades throughout Europe and is found at highest frequencies in Bosnia and Herzegovina 65%,[79] Croatia, Norway, Denmark, Sardinia, Serbia, Sweden, parts of Germany, Romania/Moldova and other countries in the Balkan Peninsula and Scandinavia. This clade is found at its highest expression by far in Europe and may have been there since before the LGM.[35] While the older branch of the Balkans is linked to the Albanians, haplogroup I reached Scandinavia around 5000 BC and this branch is linked to the Germanic languages, which it since the 6th century imposed on most R1b (Celtic) and some R1a (Slavic and Aryan, eg.: Boioaria/Bavaria, Korontania/Austria, Serbia/Saxony, Lusatia, Pomerania…) peoples.

- Haplogroup E1b1b (formerly known as E3b) represents the last major direct migration from Africa into Europe. It is believed to have first appeared in the Horn of Africa approximately 26,000 years ago and dispersed to North Africa and the Near East during the late Paleolithic and Mesolithic periods. E1b1b lineages are closely linked to the diffusion of Afroasiatic languages. Although present throughout Europe, it peaks in the western Balkan region amongst Albanians and their neighbors. It is also common in Italy and the Iberian peninsula. Haplogroup E1b1b1, mainly in the form of its E1b1b1a2 (E-V13) sub-clade, reaches frequencies above 47% around the area of Kosovo.[80] This clade is thought to have arrived in Europe from western Asia either in the later Mesolithic,[81] or the Neolithic.[82] North Africa subclade E-M81 is also present in Spain and Portugal.

- Haplogroup R1b is common all over Europe, with R1b1a1a2 especially common in Western Europe.[83][84][85] Nearly all of this R1b in Europe is in the form of the R1b1a2 (2011 name) (R-M269) sub-clade, specifically within the R-L23 sub-sub-clade whereas R1b found in Central Asia, western Asia and Africa tends to be in other clades. It has also been pointed out that outlier types are present in Europe and are particularly notable in some areas such as Sardinia and Armenia.[86] Haplogroup R1b frequencies vary from highs in western Europe in a steadily decreasing cline with growing distance from the Atlantic: 80–90% (Welsh, Basque, Irish, Scots, Bretons) around 70–80% in other areas of Spain, Britain and France and around 40–60% in most other parts of western Europe like eastern Germany, and northern-central Italy . It drops outside this area and is around 30% or less in areas such as southern Italy, Sweden, Poland, the Balkans and Cyprus. R1b remains the most common clade as one moves east to Germany, while farther east, in Poland, R1a is more common (see below).[87] In southeastern Europe, R1b drops behind R1a in the area in and around Hungary and Serbia but is more common both to the south and north of this region.[88] R1b in Western Europe is dominated by at least two sub-clades, R-U106, which is distributed from the east side of the Rhine into northern and central Europe (with a strong presence in England) and R-P312, which is most common west of the Rhine, including the British Isles.[84][85] Some have posited that this haplogroup's presence in Europe dates back to the LGM, while others link it to the spread of the Centum branch of the Indo-European languages.

- The oldest human remains found to carry R1b so far are an individual from the Epigravettian culture context in Italy (Villabruna) who lived circa 12,000 BC and reportedly belonged to R1b1a (L754), and the 7,000 year-old remains of a hunter-gatherer, belonging to the Samara culture of the Volga River area who carried R1b1* (R-L278*).

- Haplogroup R1a, almost entirely in the R1a1a sub-clade, is prevalent in much of Eastern and Central Europe (also in South and Central Asia). For example, there is a sharp increase in R1a1 and decrease in R1b1b2 as one goes east from Germany to Poland.[87] It also has a substantial presence in Scandinavia (particularly Norway).[89][90] In the Baltic countries R1a frequencies decrease from Lithuania (45%) to Estonia (around 30%).[91] Although less prominent in Western Europe, still present in Scotland (Norse via Norway), Britain (Sarmatians of Roman cavalry), Spain (Aryan Magi/Druids and Slavs/Sarmatians of Cantabria) and Italy (Eneti/Veneti of Veneto). Due to Turkic (incl.Turko-Mongol) and Semitic (Khasar and Islamic) invasions nearly extinct in Central Asia, West Asia and Middle East (Mesopotamia, Anatolia, Syria). Many people link this haplogroup to the spread of the Indo-European languages in Europe, while some limit this connection to the Satem branch of said language family.

Putting aside small enclaves, there are also several haplogroups apart from the above four that are less prominent or most common only in certain areas of Europe.

- Haplogroup G, the original Neolithic Europeans (Caucasians), is common in most parts of Europe at a low frequency, reaching peaks above 70% around Georgia and among the Madjars (although living in Asia they border the eastern perimeter of Europe), up to 20% in Sardinia, 12% in Corsica and Uppsala (Sweden), 11% in the Balkans and Portugal, 10% in Spain and 9% in European Russia. This clade is also found in the Near East. Apparently haplogroup G was gradually replaced by their direct neighbours, the more agricultural and sedentary oriented R1, and upon the development of chariot they finally together formed the Hittites introducing Iron Age.

- Haplogroup N, the Neolithic deer hunters is common only in the northeast of Europe and in the form of its N1c1 sub-clade reaches frequencies of approximately 60% among Finns and approximately 40% among Estonians, Latvians, and Lithuanians.

- Haplogroup J2, in various sub-clades (J2a, J2b), is found in levels of around 15–30% in parts of the Balkans and Italy and is common all over Europe and especially the Mediterranean basin[92]

Matrilineal studies

There have been a number of studies about the mitochondrial DNA haplogroups (mtDNA) in Europe. In contrast to Y DNA haplogroups, mtDNA haplogroups did not show as much geographical patterning, but were more evenly ubiquitous. Apart from the outlying Saami, all Europeans are characterised by the predominance of haplogroups H, U and T. The lack of observable geographic structuring of mtDNA may be due to socio-cultural factors, namely the phenomena of polygyny and patrilocality.[93] According to the University of Oulu Library in Finland:

Classical polymorphic markers (i.e. blood groups, protein electromorphs and HLA antigenes) have suggested that Europe is a genetically homogeneous continent with a few outliers such as the Saami, Sardinians, Icelanders and Basques (Cavalli-Sforza et al. 1993, Piazza 1993). The analysis of mtDNA sequences has also shown a high degree of homogeneity among European populations, and the genetic distances have been found to be much smaller than between populations on other continents, especially Africa (Comas et al. 1997).

The mtDNA haplogroups[94] of Europeans are surveyed by using a combination of data from RFLP analysis of the coding region and sequencing of the hypervariable segment I. About 99% of European mtDNAs fall into one of ten haplogroups: H, I, J, K, M, T, U, V, W or X (Torroni et al. 1996a). Each of these is defined by certain relatively ancient and stable polymorphic sites located in the coding region (Torroni et al. 1996a)... Haplogroup H, which is defined by the absence of an AluI site at bp 7025, is the most prevalent, comprising half of all Europeans (Torroni et al. 1996a, Richards et al. 1998)... Six of the European haplogroups (H, I, J, K, T and W) are essentially confined to European populations (Torroni et al. 1994, 1996a), and probably originated after the ancestral Caucasoids became genetically separated from the ancestors of the modern Africans and Asians.[95]

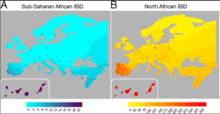

Genetic studies suggest some maternal gene flow to eastern Europe from eastern Asia or southern Siberia 13,000 – 6,600 years BP.[96] Analysis of Neolithic skeletons in the Great Hungarian Plain found a high frequency of eastern Asian mtDNA haplogroups, some of which survive in modern eastern European populations.[96] Maternal gene flow to Europe from sub-Saharan Africa began as early as 11,000 years BP, although the majority of lineages, approximately 65%, are estimated to have arrived more recently, including during the Romanization period, the Arab conquests of southern Europe, and during the Atlantic slave trade.[97]

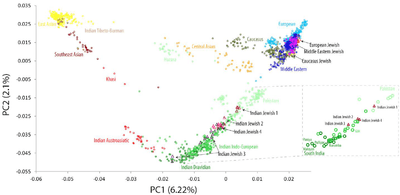

Relation between Europeans and other populations

A 2007 study by Bauchet, which utilised about 10,000 autosomal DNA SNPs arrived at similar results. Principal component analysis clearly identified four widely dispersed groupings, corresponding to Africa, Europe, Central Asia and South Asia. PC1 separated Africans from the other populations, PC2 divided Asians from Europeans and Africans, whilst PC3 split Central Asians apart from South Asians.[98]

| Northwestern Europe (CEU) | Yoruba | Han Chinese | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

NorthwesternEurope (CEU) |

0.1530 | 0.1100 | |

| Yoruba | 0.1530 | 0.1900 | |

| Han Chinese | 0.1100 | 0.1900 |

| Europe | America | East Asia | Oceania | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| America | 9.5 | |||

| East Asia | 9.7 | 8.9 | ||

| Oceania | 13.5 | 14.6 | 10 | |

| Africa | 16.6 | 22.6 | 20.6 | 24.7 |

According to Cavalli-Sforza's work, all non-African populations are more closely related to each other than to Africans; supporting the hypothesis that all non-Africans descend from a single old-African population. The genetic distance from Africa to Europe (16.6) was found to be shorter than the genetic distance from Africa to East Asia (20.6), and much shorter than that from Africa to Australia (24.7). He explains:

... both Africans and Asians contributed to the settlement of Europe, which began about 40,000 years ago. It seems very reasonable to assume that both continents nearest to Europe contributed to its settlement, even if perhaps at different times and maybe repeatedly. It is reassuring that the analysis of other markers also consistently gives the same results in this case. Moreover, a specific evolutionary model tested, i.e., that Europe is formed by contributions from Asia and Africa, fits the distance matrix perfectly (6). In this simplified model, the migrations postulated to have populated Europe are estimated to have occurred at an early date (30,000 years ago), but it is impossible to distinguish, on the basis of these data, this model from that of several migrations at different times. The overall contributions from Asia and Africa were estimated to be around two-thirds and one-third, respectively".[100][101][102]

This particular model used an Out of Africa migration 100,000 years ago, which separated Africans from non-Africans, followed by a single admixture event 30,000 years ago leading to the formulation of the European population. The admixture event consisted of a source population that was 35% African and 65% East Asian. However, the study notes that a more realistic scenario would include several admixture events occurring over a sustained period. In particular, they cite the spread of farming from a source population in West Asia 5000–9000 years ago that may have played a role in the genetic relatedness of Africans and Europeans, since West Asia is sandwiched in between Africa and Central Asia.[100][101][102]

The model assumed an out of Africa migration 100kya and a single admixture event 30kya. However, most contemporary studies have more recent dates that place the out of Africa migration 50-70kya. The study also involved a direct comparison between Sub-Saharan Africans (Central Africans and Senegalese) and Europeans. North African populations were omitted from the study. These considerations might help explain the apparent short genetic distance between Europeans and Africans.[100][101][102]

European population sub-structure

Europe is relatively genetically homogeneous, but distinct sub-population patterns of various types of genetic markers have been found,[103] particularly along a southeast-northwest cline.[104] For example, Cavalli-Sforza’s principal component analyses revealed five major clinal patterns throughout Europe, and similar patterns have continued to be found in more recent studies.[105]

- A cline of genes with highest frequencies in the Middle East, spreading to lowest levels northwest. Cavalli-Sforza originally described this as faithfully reflecting the spread of agriculture in Neolithic times. This has been the general tendency in interpretation of all genes with this pattern.

- A cline of genes with highest frequencies among Finnish and Sami in the extreme north east, and spreading to lowest frequencies in the south west.

- A cline of genes with highest frequencies in the area of the lower Don and Volga rivers in southern Russia, and spreading to lowest frequencies in Spain, Southern Italy, Greece and the areas inhabited by Saami speakers in the extreme north of Scandinavia. Cavalli-Sforza associated this with the spread of Indo-European languages, which he links in turn to a "secondary expansion" after the spread of agriculture, associated with animal grazing.

- A cline of genes with highest frequencies in the Balkans and Southern Italy, spreading to lowest levels in Britain and the Basque country. Cavalli-Sforza associates this with "the Greek expansion, which reached its peak in historical times around 1000 and 500 BC but which certainly began earlier".

- A cline of genes with highest frequencies in the Basque country, and lower levels beyond the area of Iberia and Southern France. In perhaps the most well-known conclusion from Cavalli-Sforza, this weakest of the five patterns was described as isolated remnants of the pre-Neolithic population of Europe, "who at least partially withstood the expansion of the cultivators". It corresponds roughly to the geographical spread of rhesus negative blood types. In particular, the conclusion that the Basques are a genetic isolate has become widely discussed, but also a controversial conclusion.

He also created a phylogenetic tree to analyse the internal relationships among Europeans. He found four major 'outliers'- Basques, Sami, Sardinians and Icelanders;[106] a result he attributed to their relative isolation (note: the Icelanders and the Sardinians speak Indo-European languages, while the other two groups do not). Greeks and Yugoslavs represented a second group of less extreme outliers. The remaining populations clustered into several groups : "Celtic", "Germanic", "south-western Europeans", "Scandinavians" and "eastern Europeans".[107]

A study in May 2009[108] of 19 populations from Europe using 270,000 SNPs highlighted the genetic diversity of European populations corresponding to the northwest to southeast gradient and distinguished "four several distinct regions" within Europe:

- Finland, showing the greatest distance to the rest of Europeans.

- the Baltic region (Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania), western Russia and eastern Poland.

- Central and Western Europe.

- Italy, "with the southern Italians being more distant".

In this study, barrier analysis revealed "genetic barriers" between Finland, Italy and other countries and that barriers could also be demonstrated within Finland (between Helsinki and Kuusamo) and Italy (between northern and southern part, Fst=0.0050). Fst (Fixation index) was found to correlate considerably with geographic distances ranging from ≤0.0010 for neighbouring populations to 0.0200–0.0230 for Southern Italy and Finland. For comparisons, pair-wise Fst of non-European samples were as follows: Europeans – Africans (Yoruba) 0.1530; Europeans – Chinese 0.1100; Africans (Yoruba) – Chinese 0.1900.[109]

A study by Chao Tian in August 2009 extended the analysis of European population genetic structure to include additional southern European groups and Arab populations (Palestinians, Druzes...) from the Near-East. This study determined autosomal Fst between 18 population groups and concluded that, in general, genetic distances corresponded to geographical relationships with smaller values between population groups with origins in neighbouring countries/regions (for example, Greeks/Tuscans: Fst=0.0010, Greeks/Palestinians: Fst=0.0057) compared with those from very different regions in Europe (for example Greeks/Swedish: Fst=0.0087, Greeks/Russians: Fst=0.0108).[110][111]

Autosomal DNA

Seldin (2006) used over 5,000 autosomal SNPs. It showed "a consistent and reproducible distinction between ‘northern’ and ‘southern’ European population groups". Most individual participants with southern European ancestry (Italians, Greeks, Portuguese, Spaniards), and Ashkenazi Jews have >85% membership in the southern population; and most northern, western, central, and eastern Europeans (Swedes, English, Irish, Germans, and Ukrainians) have >90% in the northern population group. However, many of the participants in this study were actually American citizens who self-identified with different European ethnicities based on self-reported familial pedigree.[112]

A similar study in 2007 using samples exclusively from Europe found that the most important genetic differentiation in Europe occurs on a line from the north to the south-east (northern Europe to the Balkans), with another east-west axis of differentiation across Europe. Its findings were consistent with earlier results based on mtDNA and Y-chromosonal DNA that support the theory that modern Iberians (Spanish and Portuguese) hold the most ancient European genetic ancestry, as well as separating Basques and Sami from other European populations.[98]

It suggested that the English and Irish cluster with other Northern and Eastern Europeans such as Germans and Poles, while some Basque and Italian individuals also clustered with Northern Europeans. Despite these stratifications, it noted the unusually high degree of European homogeneity: "there is low apparent diversity in Europe with the entire continent-wide samples only marginally more dispersed than single population samples elsewhere in the world".[98]

In 2008, two international research teams published analyses of large-scale genotyping of large samples of Europeans, using over 300,000 autosomal SNPs. With the exception of usual isolates such as Basques, Finns and Sardinians, the European population lacked sharp discontinuities (clustering) as previous studies have found (see Seldin et al. 2006 and Bauchet et al. 2007[98]), although there was a discernible south to north gradient. Overall, they found only a low level of genetic differentiation between subpopulations, and differences which did exist were characterised by a strong continent-wide correlation between geographic and genetic distance. In addition, they found that diversity was greatest in southern Europe due a larger effective population size and/or population expansion from southern to northern Europe.[113] The researchers take this observation to imply that genetically, Europeans are not distributed into discrete populations.[114][115]

A study on north-eastern populations, published in March 2013, found that Komi peoples formed a pole of genetic diversity that is distinct from other populations.[116]

Autosomal genetic distances (Fst) based on SNPs (2009)

The genetic distance between populations is often measured by Fixation index (Fst), based on genetic polymorphism data, such as single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) or microsatellites. Fst is a special case of F-statistics, the concept developed in the 1920s by Sewall Wright. Fst is simply the correlation of randomly chosen alleles within the same sub-population relative to that found in the entire population. It is often expressed as the proportion of genetic diversity due to allele frequency differences among populations.

The values range from 0 to 1. A zero value implies that the two populations are panmixis, that they are interbreeding freely. A value of one would imply that the two populations are completely separate. The greater the Fst value, the greater the genetic distance. Essentially, these low Fst values suggest that the majority of genetic variation is at the level of individuals within the same population group (~ 85%); whilst belonging to a different population group within same ‘race’/ continent, and even to different racial/ continental groups added a much smaller degree of variation (3–8%; 6–11%, respectively).

| Italian Americans | Palestinians | Swedes | Druzes | Spaniards | Germans | Russians | Irish | Greek Americans | Ashkenazi Jews | Circassians | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Italian Americans | 0.0064 | 0.0064 | 0.0057 | 0.0010 | 0.0029 | 0.0088 | 0.0048 | 0.0000 | 0.0040 | 0.0067 | |

| Palestinians | 0.0064 | 0.0191 | 0.0064 | 0.0101 | 0.0136 | 0.0202 | 0.0170 | 0.0057 | 0.0093 | 0.0108 | |

| Swedes | 0.0064 | 0.0191 | 0.0167 | 0.0040 | 0.0007 | 0.0030 | 0.0020 | 0.0084 | 0.0120 | 0.0117 | |

| Druzes | 0.0057 | 0.0064 | 0.0167 | 0.0096 | 0.0121 | 0.0194 | 0.0154 | 0.0052 | 0.0088 | 0.0092 | |

| Spaniards | 0.0010 | 0.0101 | 0.0040 | 0.0096 | 0.0015 | 0.0070 | 0.0037 | 0.0035 | 0.0056 | 0.0090 | |

| Germans | 0.0029 | 0.0136 | 0.0007 | 0.0121 | 0.0015 | 0.0030 | 0.0010 | 0.0039 | 0.0072 | 0.0089 | |

| Russians | 0.0088 | 0.0202 | 0.0030 | 0.0194 | 0.0070 | 0.0030 | 0.0038 | 0.0108 | 0.0137 | 0.0120 | |

| Irish | 0.0048 | 0.0170 | 0.0020 | 0.0154 | 0.0037 | 0.0010 | 0.0038 | 0.0067 | 0.0109 | 0.0110 | |

| Greek Americans | 0.0000 | 0.0057 | 0.0084 | 0.0052 | 0.0035 | 0.0039 | 0.0108 | 0.0067 | 0.0042 | 0.0054 | |

| Ashkenazi Jews | 0.0040 | 0.0093 | 0.0120 | 0.0088 | 0.0056 | 0.0072 | 0.0137 | 0.0109 | 0.0042 | 0.0107 | |

| Circassians | 0.0067 | 0.0108 | 0.0117 | 0.0092 | 0.0090 | 0.0089 | 0.0120 | 0.0110 | 0.0054 | 0.0107 |

CEU – Utah residents with ancestry from Northern and Western Europe.

| Austria | Bulgaria | Czech Republic | Estonia | Finland (Helsinki) | Finland (Kuusamo) | France | Northern Germany | Southern Germany | Hungary | Northern Italy | Southern Italy | Latvia | Lithuania | Poland | Russia | Spain | Sweden | Switzerland | CEU | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | 1.14 | 1.08 | 1.58 | 2.24 | 3.30 | 1.16 | 1.10 | 1.04 | 1.04 | 1.49 | 1.79 | 1.85 | 1.70 | 1.19 | 1.47 | 1.41 | 1.21 | 1.19 | 1.12 | Austria | |

| Bulgaria | 1.14 | 1.21 | 1.70 | 2.19 | 2.91 | 1.22 | 1.32 | 1.19 | 1.10 | 1.32 | 1.38 | 1.86 | 1.73 | 1.29 | 1.53 | 1.30 | 1.47 | 1.13 | 1.29 | Bulgaria | |

| Czech Republic | 1.08 | 1.21 | 1.42 | 2.20 | 3.26 | 1.35 | 1.15 | 1.16 | 1.06 | 1.69 | 2.04 | 1.62 | 1.48 | 1.09 | 1.27 | 1.63 | 1.26 | 1.37 | 1.21 | Czech Republic | |

| Estonia | 1.58 | 1.70 | 1.42 | 1.71 | 2.80 | 2.08 | 1.53 | 1.70 | 1.41 | 2.42 | 2.93 | 1.24 | 1.28 | 1.17 | 1.21 | 2.54 | 1.49 | 2.16 | 1.59 | Estonia | |

| Finland (Helsinki) | 2.24 | 2.19 | 2.20 | 1.71 | 1.86 | 2.69 | 2.17 | 2.35 | 1.87 | 2.82 | 3.37 | 2.31 | 2.33 | 1.75 | 2.10 | 3.14 | 1.89 | 2.77 | 1.99 | Finland (Helsinki) | |

| Finland (Kuusamo) | 3.30 | 2.91 | 3.26 | 2.80 | 1.86 | 3.72 | 3.27 | 3.46 | 2.68 | 3.64 | 4.18 | 3.33 | 3.37 | 2.49 | 3.16 | 4.21 | 2.87 | 3.83 | 2.89 | Finland (Kuusamo) | |

| France | 1.16 | 1.22 | 1.35 | 2.08 | 2.69 | 3.72 | 1.25 | 1.12 | 1.16 | 1.38 | 1.68 | 2.40 | 2.20 | 1.44 | 1.94 | 1.13 | 1.38 | 1.10 | 1.13 | France | |

| Northern Germany | 1.10 | 1.32 | 1.15 | 1.53 | 2.17 | 3.27 | 1.25 | 1.08 | 1.11 | 1.72 | 2.14 | 1.84 | 1.66 | 1.18 | 1.49 | 1.62 | 1.12 | 1.36 | 1.06 | Northern Germany | |

| Southern Germany | 1.04 | 1.19 | 1.16 | 1.70 | 2.35 | 3.46 | 1.12 | 1.08 | 1.08 | 1.53 | 1.85 | 1.20 | 1.84 | 1.23 | 1.58 | 1.40 | 1.21 | 1.17 | 1.07 | Southern Germany | |

| Hungary | 1.04 | 1.10 | 1.06 | 1.41 | 1.87 | 2.68 | 1.16 | 1.11 | 1.08 | 1.42 | 1.63 | 1.58 | 1.46 | 1.14 | 1.28 | 1.32 | 1.22 | 1.16 | 1.13 | Hungary | |

| Northern Italy | 1.49 | 1.32 | 1.69 | 2.42 | 2.82 | 3.64 | 1.38 | 1.72 | 1.53 | 1.42 | 1.54 | 2.64 | 2.48 | 1.75 | 2.24 | 1.42 | 1.86 | 1.36 | 1.56 | Northern Italy | |

| Southern Italy | 1.79 | 1.38 | 2.04 | 2.93 | 3.37 | 4.18 | 1.68 | 2.14 | 1.85 | 1.63 | 1.54 | 3.14 | 2.96 | 1.99 | 2.68 | 1.67 | 2.28 | 1.54 | 1.84 | Southern Italy | |

| Latvia | 1.85 | 1.86 | 1.62 | 1.24 | 2.31 | 3.33 | 2.40 | 1.84 | 1.20 | 1.58 | 2.64 | 3.14 | 1.20 | 1.26 | 1.84 | 2.82 | 1.89 | 2.52 | 1.87 | Latvia | |

| Lithuania | 1.70 | 1.73 | 1.48 | 1.28 | 2.33 | 3.37 | 2.20 | 1.66 | 1.84 | 1.46 | 2.48 | 2.96 | 1.20 | 1.20 | 1.26 | 2.62 | 1.74 | 2.29 | 1.74 | Lithuania | |

| Poland | 1.19 | 1.29 | 1.09 | 1.17 | 1.75 | 2.49 | 1.44 | 1.18 | 1.23 | 1.14 | 1.75 | 1.99 | 1.26 | 1.20 | 1.18 | 1.66 | 1.30 | 1.46 | 1.28 | Poland | |

| Russia | 1.47 | 1.53 | 1.27 | 1.21 | 2.10 | 3.16 | 1.94 | 1.49 | 1.58 | 1.28 | 2.24 | 2.68 | 1.84 | 1.26 | 1.18 | 2.32 | 1.59 | 1.20 | 1.56 | Russia | |

| Spain | 1.41 | 1.30 | 1.63 | 2.54 | 3.14 | 4.21 | 1.13 | 1.62 | 1.40 | 1.32 | 1.42 | 1.67 | 2.82 | 2.62 | 1.66 | 2.32 | 1.73 | 1.16 | 1.34 | Spain | |

| Sweden | 1.21 | 1.47 | 1.26 | 1.49 | 1.89 | 2.87 | 1.38 | 1.12 | 1.21 | 1.22 | 1.86 | 2.28 | 1.89 | 1.74 | 1.30 | 1.59 | 1.73 | 1.50 | 1.09 | Sweden | |

| Switzerland | 1.19 | 1.13 | 1.37 | 2.16 | 2.77 | 3.83 | 1.10 | 1.36 | 1.17 | 1.16 | 1.36 | 1.54 | 2.52 | 2.29 | 1.46 | 1.20 | 1.16 | 1.50 | 1.21 | Switzerland | |

| CEU | 1.12 | 1.29 | 1.21 | 1.59 | 1.99 | 2.89 | 1.13 | 1.06 | 1.07 | 1.13 | 1.56 | 1.84 | 1.87 | 1.74 | 1.28 | 1.56 | 1.34 | 1.09 | 1.21 | CEU | |

| Austria | Bulgaria | Czech Republic | Estonia | Finland (Helsinki) | Finland (Kuusamo) | France | Northern Germany | Southern Germany | Hungary | Northern Italy | Southern Italy | Latvia | Lithuania | Poland | Russia | Spain | Sweden | Switzerland | CEU | ||

History of research

Classical genetic markers (by proxy)

One of the first scholars to perform genetic studies was Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza. He used classical genetic markers to analyse DNA by proxy. This method studies differences in the frequencies of particular allelic traits, namely polymorphisms from proteins found within human blood (such as the ABO blood groups, Rhesus blood antigens, HLA loci, immunoglobulins, G6PD isoenzymes, among others). Subsequently his team calculated genetic distance between populations, based on the principle that two populations that share similar frequencies of a trait are more closely related than populations that have more divergent frequencies of the trait.[119]

From this, he constructed phylogenetic trees that showed genetic distances diagrammatically. His team also performed principal component analyses, which is good at analysing multivariate data with minimal loss of information. The information that is lost can be partly restored by generating a second principal component, and so on.[120] In turn, the information from each individual principal component (PC) can be presented graphically in synthetic maps. These maps show peaks and troughs, which represent populations whose gene frequencies take extreme values compared to others in the studied area.[119]

Peaks and troughs usually connected by smooth gradients are called clines. Genetic clines can be generated by adaptation to environment (natural selection), continuous gene flow between two initially different populations or a demographic expansion into a scarcely populated environment, with little initial admixture with existing populations.[121] Cavalli-Sforza connected these gradients with postulated pre-historic population movements, based on archaeological and linguistic theories. However, given that the time depths of such patterns are not known, "associating them with particular demographic events is usually speculative".[93]

Direct DNA analysis

Studies using direct DNA analysis are now abundant and may use mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), the non-recombining portion of the Y chromosome (NRY), or even autosomal DNA. MtDNA and NRY DNA share some similar features, which have made them particularly useful in genetic anthropology. These properties include the direct, unaltered inheritance of mtDNA and NRY DNA from mother to offspring and father to son, respectively, without the 'scrambling' effects of genetic recombination. We also presume that these genetic loci are not affected by natural selection and that the major process responsible for changes in base pairs has been mutation (which can be calculated).[122]

The smaller effective population size of the NRY and mtDNA enhances the consequences of drift and founder effect, relative to the autosomes, making NRY and mtDNA variation a potentially sensitive index of population composition.[93][30][123] These biologically plausible assumptions are not concrete; Rosser suggests that climatic conditions may affect the fertility of certain lineages.[93]

The underlying mutation rate used by the geneticists is more questionable. They often use different mutation rates and studies frequently arrive at vastly different conclusions.[93] NRY and mtDNA may be so susceptible to drift that some ancient patterns may have become obscured. Another assumption is that population genealogies are approximated by allele genealogies. Guido Barbujani points out that this only holds if population groups develop from a genetically monomorphic set of founders. Barbujani argues that there is no reason to believe that Europe was colonised by monomorphic populations. This would result in an overestimation of haplogroup age, thus falsely extending the demographic history of Europe into the Late Paleolithic rather than the Neolithic era.[124] Greater certainty about chronology may be obtained from studies of ancient DNA (see below), but so far these have been comparatively few.

Whereas Y-DNA and mtDNA haplogroups represent but a small component of a person’s DNA pool, autosomal DNA has the advantage of containing hundreds of thousands of examinable genetic loci, thus giving a more complete picture of genetic composition. Descent relationships can only be determined on a statistical basis, because autosomal DNA undergoes recombination. A single chromosome can record a history for each gene. Autosomal studies are much more reliable for showing the relationships between existing populations, but do not offer the possibilities for unravelling their histories in the same way as mtDNA and NRY DNA studies promise, despite their many complications.

Genetic studies operate on numerous assumptions and suffer from methodological limitations, such as selection bias and confounding phenomena like genetic drift, foundation and bottleneck effects cause large errors, particularly in haplogroup studies. No matter how accurate the methodology, conclusions derived from such studies are compiled on the basis of how the author envisages their data fits with established archaeological or linguistic theories.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Genetic studies on European populations. |

References

Inline citations

- ↑ L. Kovacevic et al., "Standing at the Gateway to Europe - The Genetic Structure of Western Balkan Populations Based on Autosomal and Haploid Markers", PLOS One, 22 August 2014, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0105090

- ↑ Gyaneshwer Chaubey et al "Genetic affinities of the Jewish populations of India" Scientific Reports 6, Article number: 19166 (2016) doi:10.1038/srep19166.

- 1 2 A. Seguin-Orlando et al., "Genomic structure in Europeans dating back at least 36,200 years", Science, 6 November 2014, DOI: 10.1126/science.aaa0114.

- ↑ Michael Dannemann 1 and Janet Kelso, "The Contribution of Neanderthals to Phenotypic Variation in Modern Humans", The American Journal of Human Genetics 101, 578–589, October 5, 2017.

- 1 2 S. Beleza et al., "The Timing of Pigmentation Lightening in Europeans", Molecular Biology and Evolution, Volume 30, Issue 1, 1 January 2013, Pages 24–35, doi:10.1093/molbev/mss207. "As previously emphasized (Jablonski and Chaplin 2000), it is likely that the climatic conditions prevailing during the last glaciation favored cultural modifications that limited exposure to UVR, like shelter seeking and the wearing of more protective clothing. Moreover, seasonality (differences in solar radiation between the summer and the winter) is thought to have significantly increased from 18,000 to 10,000 years ago, extending the duration “vitamin D winters” and augmenting the risks of vitamin D insufficiency (COHMAP Consortium 1988; Gamble and Soffer 1990; Jablonski 2004; Parra 2007). Additionally, it is conceivable that population growth after the LGM was also an important factor in the onset of the selective sweeps observed for these three genes in Europe. As previously noted (Hawks et al. 2007; Karasov et al. 2010; Pritchard et al. 2010), effective population size is one of the most important factors limiting the availability of adaptive mutations."

- ↑ E. R. Jones et al., "Upper Palaeolithic genomes reveal deep roots of modern Eurasians", Nature Communications volume 6, Article number: 8912 (2015) doi:10.1038/ncomms9912.

- ↑ Population replacement in the Neolithic, and again in the Bronze Age, was nearly complete in Prehistoric Britain, the Mesolithic WHG population accounting for just about 10% of the ancestry of the modern indigenous British population. Olalde I. et al. (2018), "The Beaker phenomenon and the genomic transformation of northwest Europe", Nature 555 (7695), doi: 10.1038/nature25738.

- ↑ Lazaridis et al., "Ancient human genomes suggest three ancestral populations for present-day Europeans", Nature, 513(7518), 18 September 2014, 409–413, doi: 10.1038/nature13673 (Supplemental Information).

- ↑ Since Lazaridis et al. (2014), further studies have refined the picture of interbreeding between EEF and WHG. In a 2017 analysis of 180 ancient DNA datasets of the Chalcolithic and Neolithic periods from Hungary, Germany and Spain evidence was found of a prolongued period of EEF-WHG interbreeding. Admixture took place regionally, from local hunter-gatherer populations, so that populations from the three regions (Germany, Iberia and Hungary) were genetically distinguishable at all stages of the Neolithic period, with a gradually increasing ratio of WHG ancestry of farming populations over time. This suggests that after the initial expansion of early farmers, there were no further long-range migrations substantial enough to homogenize the farming population, and that farming and hunter-gatherer populations existed side by side for many centuries, with ongoing gradual admixture throughout the 5th to 4th millennia BC (rather than a single admixture event on initial contact). Lipson et al., "Parallel palaeogenomic transects reveal complex genetic history of early European farmers", Nature 551, 368–372 (16 November 2017) doi:10.1038/nature24476.

- ↑ Lipson et al. (2017), Fig 2.

- ↑ Lazaridis et al. (2014), Supplemental Information p. 80. "Europeans form a cline between EEF and ANE and are intermediate between the Near East and WHG. Fig. 1B also suggests that Europeans are not a simple EEF-WHG mixture as, with the exception of Sardinians all others strongly deviate “northwards” along the European cline, i.e., in the same direction as ANE deviate from EEF, and indeed Sardinians are the only European population whose lowest statistic involved the EEF-WHG pairing". The highest ANE ancestry is found in North Eurasia, among the Ket people. Flegontov et al., "Genomic study of the Ket: a Paleo-Eskimo-related ethnic group with significant ancient North Eurasian ancestry" (1026), doi: 10.1038/srep20768. See also: Autosomal Maps (eupedia.com)

- 1 2 Dutchen, Stephanie (November 23, 2015). "Farming's in Their DNA". Harvard Medical School. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Fu, Qiaomei; Posth, Cosimo (May 2, 2016). "The genetic history of Ice Age Europe". Nature. Bibcode:2016Natur.534..200F. doi:10.1038/nature17993.

- 1 2 3 Richards et al. 2000

- ↑ https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322711675_Insights_into_Modern_Human_Prehistory_Using_Ancient_Genomes

- ↑ Even before the advent of genetic studies, some anthropologists believed they had discovered skeletons representing Neanderthal-modern human 'hybrids'. These results were deemed 'ambiguous'. Archaeological evidence points to an abrupt change from Neanderthal artefacts to those related to AMH during the Upper Palaeolithic.Klein RG (March 2003), "Paleoanthropology. Whither the Neanderthals?", Science, 299 (5612): 1525–7, doi:10.1126/science.1082025, PMID 12624250

- ↑ Prüfer, K.; Racimo, F.; Patterson, N.; Jay, F.; Sankararaman, S.; Sawyer, S.; et al. (2014) [Online 2013]. "The complete genome sequence of a Neanderthal from the Altai Mountains". Nature. 505 (7481): 43–49. Bibcode:2014Natur.505...43P. doi:10.1038/nature12886. PMC 4031459. PMID 24352235.

- ↑ J. Hardy; A. Pittman; A. Myers; K. Gwinn-Hardy; H.C. Fung; R. de Silva; M. Hutton; J. Duckworth (2005), "Evidence suggesting that Homo neanderthalensis contributed the H2 MAPT haplotype to Homo sapiens" (PDF), Biochemical Society Transactions, 33 (4): 582–585, doi:10.1042/bst0330582, PMID 16042549,

We suggest that the H2 haplotype is derived from Homo neanderthalensis and entered H. sapiens populations during the coexistence of these species in Europe from approx. 45 000 to 18 000 years ago and that the H2 haplotype has been under selection pressure since that time, possibly because of the role of this H1 haplotype in neurodegenerative disease."..."The tau (MAPT ) locus is very unusual. Over a region of approx. 1.8 Mb, there are two haplotype clades in European populations, H1 and H2 [6,7]. In other populations, only the H1 occurs and shows a normal pattern of recombination

- ↑ Shaw-Smith, C; Pittman, Am; Willatt, L; Martin, H; Rickman, L; Gribble, S; Curley, R; Cumming, S; Dunn, C; Kalaitzopoulos, D; Porter, K; Prigmore, E; Krepischi-Santos, Ac; Varela, Mc; Koiffmann, Cp; Lees, Aj; Rosenberg, C; Firth, Hv; De, Silva, R; Carter, Np (September 2006), "Microdeletion encompassing MAPT at chromosome 17q21.3 is associated with developmental delay and learning disability", Nature Genetics, 38 (9): 1032–7, doi:10.1038/ng1858, ISSN 1061-4036, PMID 16906163

- ↑ Zody, Mc; Jiang, Z; Fung, Hc; Antonacci, F; Hillier, Lw; Cardone, Mf; Graves, Ta; Kidd, Jm; Cheng, Z; Abouelleil, A; Chen, L; Wallis, J; Glasscock, J; Wilson, Rk; Reily, Ad; Duckworth, J; Ventura, M; Hardy, J; Warren, Wc; Eichler, Ee (August 2008), "Evolutionary toggling of the MAPT 17q21.31 inversion region", Nature Genetics, 40 (9): 1076–83, doi:10.1038/ng.193, ISSN 1061-4036, PMC 2684794, PMID 19165922

- ↑ Introgression and microcephalin FAQ John Hawks

- ↑ Almos, Pz; Horváth, S; Czibula, A; Raskó, I; Sipos, B; Bihari, P; Béres, J; Juhász, A; Janka, Z; Kálmán, J (November 2008), "H1 tau haplotype-related genomic variation at 17q21.3 as an Asian heritage of the European Gypsy population", Heredity, 101 (5): 416–9, doi:10.1038/hdy.2008.70, ISSN 0018-067X, PMID 18648385,

In this study, we examine the frequency of a 900 kb inversion at 17q21.3 in the Gypsy and Caucasian populations of Hungary, which may reflect the Asian origin of Gypsy populations. Of the two haplotypes (H1 and H2), H2 is thought to be exclusively of Caucasian origin, and its occurrence in other racial groups is likely to reflect admixture. In our sample, the H1 haplotype was significantly more frequent in the Gypsy population (89.8 vs 75.5%, P<0.001) and was in Hardy–Weinberg disequilibrium (P=0.017). The 17q21.3 region includes the gene of microtubule-associated protein tau, and this result might imply higher sensitivity to H1 haplotype-related multifactorial tauopathies among Gypsies.

- ↑ Wade, Nicholas (2009-12-02), Scientists in Germany Draft Neanderthal Genome, New York Times, retrieved 2010-05-03

- ↑ Neanderthals 'distinct from us', BBC, 2009-12-02

- ↑ Milisauskas (2002, p. 59)

- 1 2 3 Semino 2000

- ↑ Semino 2000.

- ↑ Wells 2001. Eurasian heartland.

- ↑ Tatiana M. Karafet; et al. (2008). "New binary polymorphisms reshape and increase resolution of the human Y chromosomal haplogroup tree". Genome Res. 18 (5): 830–8. doi:10.1101/gr.7172008. PMC 2336805. PMID 18385274.

- 1 2 3 Richards et al (2000)

- ↑ Torroni A, Bandelt HJ, Macaulay V, et al. (October 2001), "A signal, from human mtDNA, of postglacial recolonization in Europe", Am. J. Hum. Genet., 69 (4): 844–52, doi:10.1086/323485, PMC 1226069, PMID 11517423, retrieved 2009-07-22

- ↑ Pala, Maria; Achilli, Alessandro; Olivieri, Anna; Kashani, Baharak Hooshiar; Perego, Ugo A; Sanna, Daria; Metspalu, Ene; Tambets, Kristiina; Tamm, Erika; et al. (2009), "Mitochondrial Haplogroup U5b3: A Distant Echo of the Epipaleolithic in Italy and the Legacy of the Early Sardinians", The American Journal of Human Genetics, 84 (6): 814–21, doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.05.004, PMC 2694970, PMID 19500771, retrieved 2014-12-29

- ↑ R Wells et al. The Eurasian Heartland: A continental perspective on Y-chromosome diversity

- ↑ Semino et al. (2000)

- 1 2 Rootsi S, Magri C, Kivisild T, Benuzzi G, Help H, Bermisheva M, Kutuev I, Barać L, Peričić M, et al. (2004), "Phylogeography of Y-Chromosome Haplogroup I Reveals Distinct Domains of Prehistoric Gene Flow in Europe" (PDF), American Journal of Human Genetics, 75 (1): 128–137, doi:10.1086/422196, PMC 1181996, PMID 15162323, archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-06-24, retrieved 2009-07-04.

- ↑ Pericic et al. 2005

- ↑ Cinnioglu et al. Excavating Y-chromosome haplotype strata in Anatolia. 2003

- ↑ Pericic et al (2005) For discussion of eastern European dispersal of R1a1

- ↑ Passarino et al (2001) For Scandinavian data

- ↑ Semino (2000) general introduction

- ↑ Bilton DT, Mirol PM, Mascheretti S, Fredga K, Zima J, Searle JB; Mirol; Mascheretti; Fredga; Zima; Searle (July 1998), "Mediterranean Europe as an area of endemism for small mammals rather than a source for northwards postglacial colonization", Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 265 (1402): 1219–26, doi:10.1098/rspb.1998.0423, PMC 1689182, PMID 9699314

- 1 2 3 Dutchen, Stephanie (May 2, 2016). "History on Ice". Harvard Medical School. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mathieson, Iain; Lazaridis, Iosif (23 November 2015). "Genome-wide patterns of selection in 230 ancient Eurasians". Nature. 528: 499–503. Bibcode:2015Natur.528..499M. doi:10.1038/nature16152. PMC 4918750. PMID 26595274.

- ↑ S. Beleza et al., "The Timing of Pigmentation Lightening in Europeans", Molecular Biology and Evolution, Volume 30, Issue 1, 1 January 2013, Pages 24–35, doi:10.1093/molbev/mss207. see also: E. R. Jones, "Upper Palaeolithic genomes reveal deep roots of modern Eurasians", Nature Communications volume 6, Article number: 8912 (2015), https://www.nature.com/articles/ncomms9912 doi:10.1038/ncomms9912].

- ↑ Perlès C, Monthel G ( 2001) The Early Neolithic in Greece: The First Farming Communities in Europe. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- ↑ Runnels C (2003) The origins of the Greek Neolithic: a personal view, in Ammerman and Biagi (2003 eds).

- ↑ Milisauskas (2002, pp. 1143, 150)

- ↑ Zeder MA (2008), "Domestication and early agriculture in the Mediterranean Basin: Origins, diffusion, and impact", PNAS, 105 (33): 11597–11604, Bibcode:2008PNAS..10511597Z, doi:10.1073/pnas.0801317105, PMC 2575338, PMID 18697943.

- ↑ Milisauskas et al.:146)

- ↑ Piazza, Alberto; Cavalli-Sforza, L. L.; Menozzi, Paolo (1994), The history and geography of human genes, Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-08750-4

- ↑ Semino 2000. Here, the clade E-M35 is referred to as "Eu 4".

- ↑ Rosser et al. 2000

- ↑ Y chromosome data show a signal for a separate late-Pleistocene migration from Africa to Europe via Sinai as evidenced through the distribution of haplogroup E3b lineages, which is not manifested in mtDNA haplogroup distributions.

- 1 2 Bird, Steven (2007), "Haplogroup E3b1a2 as a Possible Indicator of Settlement in Roman Britain by Soldiers of Balkan Origin", Journal of Genetic Genealogy, 3 (2),

ISBN may be invalid – please double check

- ↑ Balaresque et al. 2010, A Predominantly Neolithic Origin for European Paternal Lineages

- ↑ Most British men are descended from ancient farmers, The Guardian, 20 January 2010

- ↑ Most European males 'descended from farmers', BBC News, 20 January 2010

- ↑ Study finds Britons are descended from farmers who left Iraq and Syria 10,000 years ago, Daily Mail, 20 January 2010

- ↑ Laura Morelli1, Daniela Contu, Federico Santoni, Michael B. Whalen, Paolo Francalacci, Francesco Cucca; et al. (9 April 2010). "A Comparison of Y-Chromosome Variation in Sardinia and Anatolia Is More Consistent with Cultural Rather than Demic Diffusion of Agriculture". PLoS ONE. 5 (4): e10419. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...510419M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0010419. PMC 2861676. PMID 20454687. Retrieved 29 April 2010.

- ↑ Haak, W.; Lazaridis, I.; Patterson, N.; Rohland, N.; Mallick, S.; Llamas, B.; Brandt, G.; Nordenfelt, S.; Harney, E.; Stewardson, K.; Fu, Q.; Mittnik, A.; Bánffy, E.; Economou, C.; Francken, M.; Friederich, S.; Pena, R. G.; Hallgren, F.; Khartanovich, V.; Khokhlov, A.; Kunst, M.; Kuznetsov, P.; Meller, H.; Mochalov, O.; Moiseyev, V.; Nicklisch, N.; Pichler, S. L.; Risch, R.; Rojo Guerra, M. A.; et al. (2015). "Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe" (PDF). Nature. 522: 207–211. arXiv:1502.02783. Bibcode:2015Natur.522..207H. doi:10.1038/nature14317. PMC 5048219. PMID 25731166.

- ↑ Callaway, E. (2015). "European languages linked to migration from the east". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2015.16919.

- ↑ Underhill, Peter A; Myres, Natalie M; Rootsi, Siiri; Metspalu, Mait; Zhivotovsky, Lev A; King, Roy J; Lin, Alice A; Chow, Cheryl-Emiliane T; Semino, Ornella; et al. (2009), "Separating the post-Glacial coancestry of European and Asian Y chromosomes within haplogroup R1a", European Journal of Human Genetics, 18 (4): 479–84, doi:10.1038/ejhg.2009.194, PMC 2987245, PMID 19888303

- ↑ Max Ingman; Ulf Gyllensten (2007). "A recent genetic link between Sami and the Volga-Ural region of Russia". European Journal of Human Genetics. 15 (1): 115–20. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201712. PMID 16985502.

- ↑ Kalevi Wiik. "Who Are the Finns?" (PDF). Retrieved 2016-03-16.

- ↑ Mirabal et al. 2009

- ↑ S Rootsi; et al. (2006). "A counter-clockwise northern route of the Y-chromosome haplogroup N from Southeast Asia towards Europe". European Journal of Human Genetics. 15 (2): 204–11. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201748. PMID 17149388. , Supplemental table 1

- 1 2 Europe's fourth ancestral 'tribe' uncovered, BBC, Nov 16, 2015.

- ↑ Zimmer, Carl (November 24, 2015). "A Key to European Evolution". New York Times. p. D4. Retrieved November 24, 2015.

- 1 2 3 Eppie R. Jones, Gloria Gonzalez-Fortes, Sarah Connell, Veronika Siska, Anders Eriksson, Rui Martiniano, Russell L. McLaughlin, Marcos Gallego Llorente, Lara M. Cassidy, Cristina Gamba, Tengiz Meshveliani, Ofer Bar-Yosef, Werner Müller, Anna Belfer-Cohen, Zinovi Matskevich, Nino Jakeli, Thomas F. G. Higham, Mathias Currat, David Lordkipanidze, Michael Hofreiter, Andrea Manica, Ron Pinhasi, Daniel G. Bradley (2015). "Upper Palaeolithic genomes reveal deep roots of modern Eurasians". Nature Communications. 6 (8912): 8912. Bibcode:2015NatCo...6E8912J. doi:10.1038/ncomms9912. PMC 4660371. PMID 26567969.

- ↑ Dutchen, Stephanie (September 17, 2014). "New Branch Added to European Family Tree". Harvard Medical School. Archived from the original on 2014-10-01. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ↑ Iosif Lazaridis; et al. (2016). "The genetic structure of the world's first farmers". bioRxiv 059311.

- ↑ Iain Mathieson; et al. (2017). "The Genomic History Of Southeastern Europe". bioRxiv 135616.

- ↑ Busby et al., Current Biology Volume 25, Issue 19, p2518–2526, 5 October 2015.

- ↑ "Pannonia and Upper Moesia. A History of the Middle Danube Provinces of the Roman Empire. Andras Mocsy. London and Boston, Routledge and Kegan Paul. ISBN 0-7100-7714-9

- ↑ Comas D, Schmid H, Braeuer S, et al. (March 2004), "Alu insertion polymorphisms in the Balkans and the origins of the Aromuns", Annals of Human Genetics, 68 (Pt 2): 120–7, doi:10.1046/j.1529-8817.2003.00080.x, PMID 15008791

- ↑ Bosch E, Calafell F, González-Neira A, et al. (July 2006), "Paternal and maternal lineages in the Balkans show a homogeneous landscape over linguistic barriers, except for the isolated Aromuns", Annals of Human Genetics, 70 (Pt 4): 459–87, doi:10.1111/j.1469-1809.2005.00251.x, PMID 16759179

- ↑ Capelli et al. (2003).