Vlachs of Serbia

|

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 35,330 (2011) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Eastern Central Serbia | |

| Languages | |

| Vlach and Serbian | |

| Religion | |

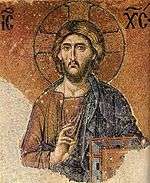

| Predominantly Eastern Orthodox | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Romanians of Serbia |

The Vlachs (endonym: Rumînji or Rumâni, Serbian: Власи/Vlasi) are an ethnic minority in eastern Serbia, culturally and linguistically related to Romanians.[1][2][3] They mostly live in the Timočka Krajina region (roughly corresponding to the districts of Bor and Zaječar), but also in Braničevo and Pomoravlje districts. A small Vlach population also exists in Smederevo and Velika Plana (Podunavlje District), and in the municipalities of Aleksinac and Kruševac (Rasina District).

History

Vlach is an exonym for the eastern Romance speaking community in the Balkans, which resulted from the occupation and colonisation of the region during the Roman Empire.[4][5] Northeastern Serbia is home to several Vlach/Romanian communities who speak dialects similar to ones in parts of western Romania: in Banat, Transylvania, and Oltenia (Lesser Wallachia). These are the Ungureni (Ungurjani, Унгурјани), Munteni (Munćani, Мунћани) and Bufeni (Bufani, Буфани). Today, about three quarters of the Vlach population speak the Ungurean subdialect which is similar to the Romanian spoken in Banat. In the 19th century other groups of Romanians originating in Oltenia (Lesser Wallachia) also settled south of the Danube.[6] These are the Țărani (Carani, Царани), who form some 25% of the modern population and speak a variety of Oltenian dialect. From the 15th through the 18th centuries large numbers of Serbs also migrated across the Danube, but in the opposite direction, to both Banat and Țara Româneasca. Significant migration ended by the establishment of the kingdoms of Serbia and Romania in the second half of the 19th century. The Vlachs of northeastern Serbia share close linguistic and cultural ties with the Vlachs in the region of Vidin in Bulgaria as well as the Romanians of Banat and Oltenia (Lesser Wallachia). Some authors consider that the majority of Vlachs/Romanians in Timočka Krajina are descendants of Romanians that migrated from Hungary in the 18th and 19th centuries.[7]

Culture

Language

The language spoken by the Vlachs consists of two distinct Romanian subdialects spoken in regions neighboring Romania: one major group of Vlachs speaks the dialect spoken in Mehedinți County in western Oltenia, while the other major group speaks a dialect similar to the one spoken in the neighboring region of Banat.

The Romanian language is not in use in local administration, not even in localities where members of the minority represent more than 15% of the population, where it would be allowed according to Serbian law.[8]

Religion

The Romanian Orthodox Church in Malajnica, built in 2004, is the first Romanian church in eastern Serbia in 170 years. Before its construction, Romanians in Timoč were not allowed to hear liturgical services in their native language.[9][10][11] Most Vlachs of Eastern Serbia are Orthodox Christians who had belonged to the Serbian Orthodox Church since the 19th century. This changed on 24 March 2009, when Serbia recognized the authority of the Romanian Orthodox Church in Valea Timocului and the confessional rights of the Vlachs.[12]

The 2006 Serbian law on religious organizations did not recognize the Romanian Orthodox Church as a traditional church, as it had received permission from the Serbian Church to operate only within Vojvodina, but not in Timočka Krajina.[8] At Malajnica, a Vlach priest belonging to the Romanian Orthodox Church encountered deliberately-raised administrative barriers when he attempted to build a church.[8][13] Other Romanian Orthodox churches are planned or under construction in Jasikovo, Ćuprija, Bigrenica and Samarinovac. Additionally, a Romanian Orthodox monastery is under construction in Malajnica. The Romanian Orthodox churches in Eastern Central Serbia are subordinated to the Protopresbyteriat Dacia Ripensis with its seat in Negotin. The protopresbyteriat is subordinated to the Romanian Orthodox diocese Dacia Felix with its seat in Vršac.

The relative isolation of the Vlachs has permitted the survival of various pre-Christian religious customs and beliefs that are frowned upon by the Orthodox Church. Vlach magic rituals are well known across modern Serbia. The Vlachs celebrate the Ospăț (hospitium, in Latin), called in Serbian praznik or slava, though its meaning is chtonic (related to the house and farmland) rather than familial. The customs of the Vlachs are very similar to those from Southern Romania (Walachia).[14]

Subgroups

The Vlach community is divided into several groups, each speaking their own dialectal variant:

- the Ţărani (Carani) of the Bor, Negotin and Zaječar regions are closer to Oltenia (Lesser Walachia) in their speech and music. The Ţărani have the saying "Nu dau un leu pe el" (He's not worth even a leu). The reference to "leu" (lion) as currency most likely goes back to the 17th century when the Dutch-issued daalder (leeuwendaalder) bearing the image of a lion was in circulation in the Romanian principalities and elsewhere in the Ottoman Empire whose own currency was habitually being debased by the government. In the Romanian principalities, as well as in Bulgaria, the leeuwendaalder (in Romanian and Bulgarian leu and lev, respectively) came to symbolize a strong currency. Indeed, on gaining independence in the 19th century both countries adopted this name for their new currencies. Since newly independent Serbia named its currency (the dinar) after the Roman denarius, the reference to the leu among the Ţărani is an indication of their connection to, if not origin in, what is now Romania.

- the Ungureni or Ungureani (Ungurjani) of Homolje are related to the Romanians of Banat and Transylvania, since Ungureni (compare with the word "Hungarians") is a term used by the Romanians of Wallachia to refer to their kin who once lived in provinces formerly part of the Kingdom of Hungary. The connection is evident not only in vocabulary, but also in the similarities of dialectal phonology and folk music motifs, as well as in sayings such as "Ducă-se pe Mureş" (May the Mureş take him/it away), a reference to the Transylvanian river. There is also a sub-group known as Ungureni Munteni (Ungurjani-Munćani), "the ungureni from the mountains".

- Bufani are immigrants from Lesser Walachia (Oltenia).

Population

.jpg)

In the 2002 census 40,054 people in Serbia declared themselves ethnic Vlachs, and 54,818 people declared themselves speakers of the Vlach language.[15] The Vlachs of Serbia are recognized as a minority, like the Romanians of Serbia, who number 34,576 according to the 2002 census. On the census, the Vlachs declared themselves either as Serbs, Vlachs or Romanians. Therefore, the "real" number of people of Vlach origin could be much greater than the number of recorded Vlachs, both due to mixed marriages with Serbs and also Serbian national feeling among some Vlachs.

In the 2011 census 35,330 people in Serbia declared themselves ethnic Vlachs, and 43,095 people declared themselves speakers of the Vlach language.[16] The Vlachs of Serbia are recognized as a minority. Therefore, the number of people of Vlach origin could be bigger than the number of recorded Vlachs, both due to mixed marriages with Serbs and also Serbian national feeling among some Vlachs.

Historical population

The following numbers from census data suggest the possible number of Vlachs:

- 1816: 97,215 Romanians (10% of Serbia's population.)[17]

- 1856: 104,343 Romanians[18]

- 1859: 122,593 Romanians

- 1866: 127,545 Romanians (10.5% of Serbia's population)[19]

- 1884: 149,713 Romanians

- 1890: 143,684 Romanians

- 1895: 159,000 Romanians (6.4% of Serbia's population)[20]

- 1921: 159,549 Romanians/Cincars by mother tongue in Yugoslavia on the South of the Danube river (this number includes the Daco-Romanians of Eastern Serbia, but also 9.451 Aromanians of Yugoslav Macedonia)

- 1931: 57,000 Romanians-Vlachs by mother tongue were recorded in Eastern Serbia (52,635 in the Morava Banovina and the rest in southern parts of Danube Banovina, south of the Danube).

- 1961: 1,330 Vlachs

- 1981: 135,000 people declared Vlach as their mother language (population figure given for the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia)[21]

- 2002: 40,054 declared Vlachs; 54,818 people declared Vlach as their mother language (population figures given for entire Serbia); 39,953 declared Vlachs, 54,726 people declared Vlach as their mother language (population figures given for Central Serbia only)[15]

- 2011: 35,330 declared Vlachs; 29,332 declared Romanians (figures include the entire population of Serbia)

The Vlach (Romanian) population of Central Serbia is concentrated mostly in the region bordered by the Morava River (west), Danube River (north) and Timok River (south-east). See also: List of settlements in Serbia inhabited by Vlachs.

According to some Romanian and Western European organizations, around 250,000 speakers of Romanian live in eastern Serbia.[22][23]

Identity

The community is known as Vlasi ("Vlachs") in Serbian, while their endonym is Rumînji, virtually the same as the Romanian endonym români pronounced [roˈmɨnʲ]. The Vlach community is highly assimilated into Serbian society, bilingual in the Serbian and Vlach languages, and adhering to the Eastern Orthodo Church.

Despite their recognition as a separate ethnic group by the Serbian government, Vlachs are cognate to Romanians in the cultural and linguistic sense. Some Romanians, as well as international linguists and anthropologists, consider Serbia's Vlachs to be a subgroup of Romanians. Additionally, the Movement of Romanians-Vlachs in Serbia, which represents some Vlachs, has called for the recognition of the Vlachs as a Romanian national minority, giving them rights similar to those of the Romanians of Vojvodina. However, the results of the last census showed that most Vlachs of Eastern Serbia opted for the Serbian exonym vlasi (= Vlachs) rather than rumuni (= Romanians).[15] As a result of serbianization, most Vlachs declared themselves to be "Serbs" on censusus taken by Communist Yugoslavia, but the number of those who preferred to declare themselves as Vlachs or Romanians significantly increased from 1991 (16,539 declared vlasi and 42 declared rumuni) to 2001 (39,953 declared vlasi and 4,157 declared rumuni).

Romania has given modest financial support to the Vlachs in Serbia for the preservation of their culture and language, since at present the Vlachs' language is not recognized officially in any localities where they form a majority, there is no education in their mother tongue, and there is no Vlach media or education funded by the Serbian state. There are also no church services in Vlach. Until very recently in the regions populated by Vlachs the official policy of the Serbian Orthodox church opposed the giving of non-Serbian baptismal names.

On the other hand, some Vlachs consider themselves to be simply Serbs that speak the Vlach language.

Vlach is commonly used as a historical umbrella term for all Latin peoples in Southeastern Europe (Romanians proper or Daco-Romanians, Aromanians, Megleno-Romanians, Istro-Romanians). After the foundation of the Romanian state in the 19th century, Romanians living in the Romanian Old Kingdom and in Austria-Hungary were only seldom called "Vlachs" by foreigners, the use of the exonym "Romanians" was encouraged even by officials, and the Romanian population ceased to use the exonym "Vlach" for their own designation. Only in the Serbian and Bulgarian Kingdom, where the officials did not encourage the population to use the modern exonym "Romanian", was the old designation "Vlach" retained, but the term "Romanian" was used in statistical reports (but only up to the Interwar period, when the designation "Romanian" was changed into "Vlach").[24] For this reason, the Romanians of Vojvodina (hence those who lived in Austria-Hungary) today prefer to use the modern exonym "Romanian", while those of Central Serbia still use the ancient exonym "Vlach". However, both groups use the endonym "Romanians", calling their language "Romanian" (română or rumână).[25][26]

In some notes of the government of Serbia, officials recognise that "certainly members of this population have similar characteristics with Romanians, and the language and folklore ride to their Romanian origin". The representatives of the Vlach minority sustain their Romanian origin.

Legal status

The ethnonym is Rumâni and the community Rumâni din Sârbie,[27] translated into English as "Romanians from Serbia".[28] They are also known in Romanian as Valahii din Serbia or Românii din Timoc.[29] Although ethnographically and linguistically related to the Romanians, within the Vlach community there are divergences on whether or not they belong to the Romanian nation and whether or not their minority should be amalgamated with the Romanian minority in Vojvodina.[8]

In a Romanian-Yugoslav agreement of November 4, 2002, the Yugoslav authorities agreed to recognize the Romanian identity of the Vlach population in Central Serbia,[30] but the agreement was not implemented.[31] In April 2005, 23 deputies from the Council of Europe, representatives from Hungary, Georgia, Lithuania, Romania, Moldova, Estonia, Armenia, Azerbaïdjan, Denmark and Bulgaria protested against Serbia's treatment of this population.[32]

The Senate of Romania postponed the ratification of Serbia`s candidature for membership in the European Union until the legal status and minority right of the Romanian (Vlach) population in Serbia is clarified.[33][34]

Predrag Balašević, president of the Vlach party of Serbia, accused the government of assimilation by using the national Vlach organization against the interests of this minority in Serbia.[35]

Since 2010, the Vlach National Council of Serbia has been led by members of leading Serbian parties (Democrat Party and Socialist Party), most of whom are ethnic Serbs having no relation to the Vlach/Romanian minority.[36] Radiša Dragojević, the current president of Vlach National Council of Serbia, who is not a Vlach, but an ethnic Serb,[37] stated that no one has the right to ask the Vlach minority in Serbia to identify themselves as Romanian or veto anything. As a response to mister Dragojević`s statement, the cultural organizations Ariadnae Filum, Društvo za kulturu Vlaha - Rumuna Srbije, Društvo Rumuna - Vlaha „Trajan“, Društvo za kulturu, jezik i religiju Vlaha - Rumuna Pomoravlja, Udruženje za tradiciju i kulturu Vlaha „Dunav“, Centar za ruralni razvoj - Vlaška kulturna inicijativa Srbija and the Vlach Party of Serbia protested and stated that it was false.[38][39]

According to a 2012 agreement between Romania and Serbia, members of the Vlach community that choose to declare as Romanians will have access to education, media and religion in the Romanian language.[40]

Notable people

- Bojan Aleksandrović, (Romanian: Boian Alexandrovici), priest, pastor of the Romanian Orthodox community in Malajnica and Remesiana, Serbia, and protopresbyter of Dacia Ripensis.

- Branko Olar, one of the best known singers of Romanian folklore from Eastern Serbia, originating from the village of Slatina near Bor

- Staniša Paunović, a well-known Romanian folklore singer, originating from Negotin, from Eastern Serbia

See also

References

- ↑ Assembly, Council of Europe: Parliamentary (2008-10-23). "Documents: Working Papers, 2008 Ordinary Session (second Part), 14-18 April 2008, Vol. 3: Documents 11464, 11471, 11513-11539". ISBN 9789287164438.

- ↑ "Istorija postojanja Vlaha". Nacionalni savet Vlaha. Nacionalni savet Vlaha. Archived from the original on 31 March 2012. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- ↑ Herrmann, J. "The situation of national minorities in Vojvodina and of the Romanian ethnic minority in Serbia". Parliamentary Assembly's Documents. Council of Europe. Retrieved 2013-12-31.

- ↑ "Vlach | European ethnic group". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2017-04-08.

- ↑ Rumen., Daskalov,; Tchavdar., Marinov, (2013-01-01). National ideologies and language policies. Brill. ISBN 9789004250765. OCLC 948626914.

- ↑ (in Serbian) Kosta Jovanović, Negotinska Krajina i Ključ, Belgrade, 1940

- ↑ Aspects of the Balkans: continuity and change. Contributions to the International Balkan Conference held at UCLA, October 23–28, 1969

- 1 2 3 4 "The situation of national minorities in Vojvodina and of the Romanian ethnic minority in Serbia" Archived 2012-01-25 at WebCite, at the Council of Europe, 14 February 2008

- ↑ "Xenophobic actions against Timoc Romanians". Archived from the original on 2012-07-16. Retrieved 2012-02-28.

- ↑ Drasko Djenovic (9 September 2005). "SERBIA: Romanian priest to pay for official destruction of his church". F18News. Forum 18 News Service. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- ↑ "Haiducul credintei din Valea Timocului, Boian Alexandrovici, decorat de presedintele Basescu" Archived 2008-09-19 at the Wayback Machine. (in Romanian)

- ↑ "Biserica Română din Timoc a fost recunoscută de către Curtea Supremă de Justiţie a Serbiei - Ziua de Vest". Archived from the original on 2011-07-26. Retrieved 2010-02-21.

- ↑ "Biserica românească din Malainiţa ameninţată din nou", BBC Romanian, 16 September 2005

- ↑ Archived July 21, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 3 "Official Results of Serbian Census 2002–Population by ethnic groups" (PDF) (in Serbian). p. 2. Archived from the original (477 KB) on 2009-02-25. and "Official Results of Serbian Census 2002–Population by language" (PDF) (in Serbian). p. 12. Archived from the original (441 KB) on 2009-02-24.

- ↑ (in Serbian) "Official Results of Serbian Census 2011–Population by ethnic groups" (PDF). (477 KB), p. 2 and "Official Results of Serbian Census 2011–Population by language" (PDF). (441 KB), p. 12

- ↑ (in Romanian) V. Arion; Vasile Pârvan; G. Vâlsan; Pericle Papahagi; G. Bogdan-Duică. România şi popoarele balcanice (1913). Tipografia Românească. Bucureşti, p. 22

- ↑ Guillaume Lejean, Ethnographie de la Turquie d'Europe, Gotha. Justus Perthes 1861

- ↑ Geographisches Handbuch zu Andrees Handatlas (Leipzig und Bielefeld, 1882): 1866 zählte man 1.058.189 Serben, 127.545 Rumänen, 24.607 Zigeuner, 2589 Deutsche und 3256 andere.

- ↑ Geographisches Handbuch zu Andrees Handatlas 1902: Fast die ganze Bevölkerung, über 2 Mill, besteht aus Serben, außerdem gab es, nach der Zählung von 1895, 159.000 Rumänen und 46.000 Zigeuner

- ↑ (in Serbian) Ranko Bugarski, Jezici, Beograd, 1996.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-04-16. Retrieved 2014-03-01.

- ↑ "Romanian". Ethnologue. 1999-02-19. Retrieved 2013-12-31.

- ↑ Serbian/Romanian. The Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia. The Vlachs/Romanians or the Romanians of Eastern Serbia and the "Vlach/Romanian question". Bor 2000/2001/2002.

- ↑ Website of the Federaţia Rumânilor din Serbie Archived 2006-10-26 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Reportaj printre românii din estul Serbiei

- ↑ "Account Suspended". Archived from the original on 2011-09-03. Retrieved 2014-03-01.

- ↑ Account Suspended Archived 2011-09-03 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ C. Constante, Anton Galopenția (1943). Românii din Timoc: Românii dinitre Dunăre, Timoc și Morava. p. 50.

Apoi, Valahii din Serbia, sunt harnici, muncitori, economi şi de mare dârzenie în privinţa portului şi a limbei.

- ↑ Adevărul, November 6, 2002: Prin acordul privind minoritatile, semnat, luni, la Belgrad, de catre presedintii Ion Iliescu si Voislav Kostunita, statul iugoslav recunoaste dreptul apartenentei la minoritatea romaneasca din Iugoslavia al celor aproape 120.000 de vlahi (cifra neoficiala), care traiesc in Valea Timocului, in Serbia de Rasarit. Reprezentantii romanilor din Iugoslavia, profesori, ziaristi, scriitori, i-au multumit, ieri, la Pancevo, sefului statului pentru aceasta intelegere cu guvernul de la Belgrad. Acordul este considerat de importanta istorica pentru romanii din Valea Timocului, care, din timpul lui Iosip Broz Tito, traiesc fara drept la invatamant si viata religioasa in limba materna, practic nerecunoscuti ca etnie. "Nu vom face ca fostul regim, sa numim noi care sunt minoritatile nationale sau sa stergem cu guma alte minoritati", a spus, ieri, Rasim Ljajic, ministrul sarb pentru minoritati, la intalnirea de la Pancevo a presedintelui cu romanii din Iugoslavia. Deocamdata, statul iugoslav nu a recunoscut prin lege statutul vlahilor de pe Valea Timocului, insa de-acum va acorda acestora dreptul la optiunea etnica, va permite, in decembrie, constituirea Consiliului Reprezentantilor Romani si va participa in Comisia mixta romano-iugoslava la monitorizarea problemelor minoritatilor sarba si romana din cele doua state. In Iugoslavia traiesc cateva sute de mii de romani. Presedintele Ion Iliescu s-a angajat, ieri, pentru o politica mai activa privind romanii din afara granitelor: "Avem mari datorii fata de romanii care traiesc in afara granitelor. Autocritic vorbind, nu ne-am facut intotdeauna datoria. De dragul de a nu afecta relatiile noastre cu vecinii, am fost mai retinuti, mai prudenti in a sustine cauza romanilor din statele vecine. (...) Ungurii ne dau lectii din acest punct de vedere", a spus presedintele, precizand ca romanii trebuie sa-si apere cauza "pe baza de buna intelegere".

- ↑ Curierul Naţional, 25 ianuarie 2003: Chiar si acordul dintre presedintii Ion Iliescu si Voislav Kostunita, semnat la sfarsitul anului trecut, nu este respectat, in ceea ce priveste minoritatile, deoarece locuitorii din Valea Timocului, numiti vlahi, nu sunt recunoscuti ca minoritari, ci doar „grup etnic“.

- ↑ Parliamentary Assembly, 28 April 2005 Archived 30 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine.: Deeply concerned over the cultural situation of the so-called “Vlach” Romanians dwelling in 154 ethnic Romanian localities 48 localities of mixed ethnic make-up between the Danube, Timok and Morava Rivers who since 1833 have been unable to enjoy ethnic rights in schools and churches

- ↑ Archived October 30, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ B92 - Vesti - Rumunija će blokirati kandidaturu?

- ↑ Власи оптужују Србију за асимилацију - Правда Archived 2012-02-12 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Драгојевић: Власи нису Румуни : Тема дана : ПОЛИТИКА

- ↑ Falşi vlahi folosiţi împotriva românilor | adevarul.ro

- ↑ B92 - Prenosimo - Ne gurajte probleme pod tepih

- ↑ B92 - Vesti - Vlasi (ni)su obespravljeni u Srbiji

- ↑ B92 - Vesti - Basesku: "Rumunski problem" naduvan

Sources

- T. R. Georgevitch (1919). The truth concerning the Rumanes in Serbia. Paris: Graphique.

- "PLATFORMA NACIONALNOG SAVETA VLAHA". Nacionalni savet Vlaha.

Further reading

- Mihai Viorel Fifor (2000), "Assimilation or Acculturation: Creating Identities in the New Europe. The Case of Vlachs in Serbia", Cultural Identity and Ethnicity in Central Europe, Cracow: Jagellonian University

- Sorescu-Marinković, Annemarie. "The Vlachs of North-Eastern Serbia: Fieldwork and Field Methods Today." Symposia–Caiete de Etnologie şi Antropologie. 2006.

- Sikimić, Biljana, and Annemarie Sorescu. "The Concept of Loneliness and Death among Vlachs in North-eastern Serbia." Symposia–Caiete de etnologie şi antropologie. 2004.

- Marinković, Annemarie Sorescu. "Vorbarĭ Rumîńesk: The Vlach on line Dictionary." Philologica Jassyensia 8.1 (2012): 47-60.

- Ivkov-Džigurski, Anđelija, et al. "The Mystery of Vlach Magic in the Rural Areas of 21st century Serbia." Eastern European Countryside 18 (2012): 61-83.

- Marinković, Annemarie Sorescu. "Cultura populară a românilor din Timoc–încercare de periodizare a cercetărilor etnologice." Philologica Jassyensia 2.1 (2006): 73-92.