Black British

| Total population | |

|---|---|

|

Black British 1,904,684 (3.0%) (2011 census)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|

| |

| 1,846,614 (3.5%) (2011 census) | |

| 36,178 (0.7%) (2011 census)[note 1] | |

| 18,276 (0.6%) (2011 census) | |

| 3,616 (0.2%) (2011 census)[1] | |

| Languages | |

| English (British English, Black British English, Caribbean English, African English), Creole languages, French, languages of Africa, other languages | |

| Religion | |

|

Predominantly Christianity (69%); minority follows Islam (15%), Traditional African religions, other faiths, or are irreligious (7%) 2011 census, Great Britain only[4] Note

| |

Black British people are British citizens of Black origins or heritage, including those of African-Caribbean (sometimes called "Afro-Caribbean") background and may include people with mixed ancestry.[5] The term has been used from the 1950s, mainly to refer to Black people from former British colonies in the West Indies (i.e., the New Commonwealth) and Africa, who are residents of the United Kingdom and who consider themselves British.

The term black has historically had a number of applications as a racial and political label and may be used in a wider sociopolitical context to encompass a broader range of non-European ethnic minority populations in Britain. This has become a controversial definition.[6] "Black British" is one of various self-designation entries used in official UK ethnicity classifications.

Black residents constituted around 3 per cent of the United Kingdom's population in 2011. The figures have increased from just under 1.15 million residents in 2001, or 2 per cent of the population, to just over 1.9 million in 2011. Over 95% of Black British live in England, particularly in England's larger urban areas, with most (over a million) Black British living in Greater London.

Terminology

Historically, the term has most commonly been used to refer to Black people of New Commonwealth origin, of both West African and South Asian descent. For example, Southall Black Sisters was established in 1979 "to meet the needs of black (Asian and Afro-Caribbean) women".[7] Note that "Asian" in the British context usually refers to people of South Asian ancestry.[8][9] "Black" was used in this inclusive political sense to mean "non-white British".[10]

In the 1970s, a time of rising activism against racial discrimination, the main communities so described were from the British West Indies and the Indian subcontinent. Solidarity against racism and discrimination sometimes extended the term at that time to the Irish population of Britain as well.[11][12]

Several organisations continue to use the term inclusively, such as the Black Arts Alliance,[13][14] who extend their use of the term to Latin Americans and all refugees,[15] and the National Black Police Association.[16] The official UK Census has separate self-designation entries for respondents to identify as "Asian British", "Black British" and "Other ethnic group".[17] Due to the Indian diaspora and in particular Idi Amin's expulsion of Asians from Uganda in 1972, many British Asians are from families that had previously lived for several generations in the British West Indies or Southeast Africa.[18]

Census classification

The 1991 UK census was the first to include a question on ethnicity. As of the 2011 UK Census, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) and the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (NISRA) allow people in England and Wales and Northern Ireland who self-identify as "Black" to select "Black African", "Black Caribbean" or "Any other Black/African/Caribbean background" tick boxes.[17] For the 2011 Scottish census, the General Register Office for Scotland (GOS) also established new, separate "African, African Scottish or African British" and "Caribbean, Caribbean Scottish or Caribbean British" tick boxes for individuals in Scotland from Africa and the Caribbean, respectively, who do not identify as "Black, Black Scottish or Black British".[19] In all of the UK censuses, persons with multiple familial ancestries can write in their respective ethnicities under a "Mixed or multiple ethnic groups" option, which includes additional "White and Black Caribbean" or "White and Black African" tick boxes in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland.[17]

Historical usage

Black British was also a term for those Black and mixed-race people in Sierra Leone (known as the Krio) who were descendants of migrants from England and Canada and identified as British.[20] They are generally the descendants of black people who lived in England in the 18th century and freed Black American slaves who fought for the Crown in the American Revolutionary War (see also Black Loyalists). In 1787, hundreds of London's black poor (a category that included the East Indian seamen known as lascars) agreed to go to this West African colony on the condition that they would retain the status of British subjects, live in freedom under the protection of the British Crown, and be defended by the Royal Navy. Making this fresh start with them were many white people, including lovers, wives, and widows of the black men.[21] In addition, nearly 1200 Black Loyalists, former American slaves who had been freed and resettled in Nova Scotia, also chose to join the new colony.[22]

History

Antiquity

There is evidence of the presence in Roman Britain of residents from multiethnic Romanised North Africa. Archaeological inscriptions suggest that most of these inhabitants were involved with the military. However, some were in the upper echelons of society. Analysis of a skull found in a Roman grave in Yorkshire indicated that it belonged to a mixed-race female. Her sarcophagus was made of stone and also contained a jet bracelet and an ivory bangle, indicating great wealth for the time.[23][24]

In 1953, the fossil of the Beachy Head Lady was found in East Sussex. The skeleton, which is thought to have originated from Sub-Saharan Africa, has been dated to around 245 AD.[25]

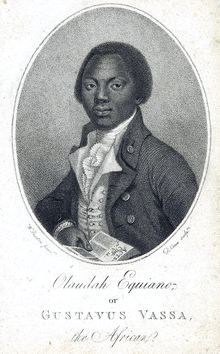

In 2007, scientists found the rare paternal haplogroup A1 in a few living British men with Yorkshire surnames. This clade is today almost exclusively found among males in West Africa, where it is also rare. The haplogroup is thought to have been brought to Britain either through enlisted soldiers during Roman Britain, or much later via the modern slave trade. Some of the known individuals who arrived through the slave route, such as Ignatius Sancho and Olaudah Equiano, attained a very high social rank. Many married into the general population.[26]

Anglo-Saxon England

A skeleton of a female found in England may indicate the existence of a very small number of black people in Britain dating to the 11th century. In 2013,[27][28] a skeleton was discovered in Fairford, Gloucestershire, which forensic anthropology revealed to be that of a sub-Saharan African woman. Her remains have been dated between the years 896 and 1025.[28] Local historians believe she may have been a bonded servant.[29]

Middle Ages

There is little evidence of Black people in Britain during the middle ages. They do however appear in the Matter of Britain, a body of Medieval literature and legendary material associated with Great Britain. Moriaen is a 13th-century Arthurian romance written in Middle Dutch. Morien is the son of Aglovale and is described "He was all black, even as I tell ye: his head, his body, and his hands were all black, saving only his teeth."[30]

16th century

Early in the 16th century, Catherine of Aragon likely brought servants from Africa among her retinue when she travelled to England to marry Henry VIII. A black musician is among the six trumpeters depicted in the royal retinue of Henry VIII in the Westminster Tournament Roll, an illuminated manuscript dating from 1511. He wears the royal livery and is mounted on horseback. The man is generally identified as the "John Blanke, the blacke trumpeter," who is listed in the payment accounts of both Henry VIII and his father, Henry VII.[31] A group of Africans were at the court of James IV of Scotland, including a drummer referred to as the "More Taubronar." Both he and John Blanke were paid wages for their services.[32]

When trade lines began to open between London and West Africa, persons from this area began coming to Britain on board merchant and slaving ships. For example, merchant John Lok brought several captives to London in 1555 from Guinea. The voyage account in Hakluyt reports that they: "were tall and strong men, and could wel agree with our meates and drinkes. The colde and moyst aire doth somewhat offend them."[33]

During the later 16th century as well as into the first two decades of the 17th century, 25 people named in the records of the small parish of St. Botolph's in Aldgate are identified as "blackamoors."[34] In the period of the war with Spain, between 1588 and 1604, there was an increase in the number of people reaching England from Spanish colonial expeditions in parts of Africa. The English freed many of these captives from enslavement on Spanish ships. They arrived in England largely as a by-product of the slave trade; some were of mixed-race African and Spanish, and became interpreters or sailors.[35] American historian Ira Berlin classified such persons as Atlantic Creoles or the Charter Generation of slaves and multi-racial workers in North America.[36] Slaver John Hawkins arrived in London with 300 captives from West Africa.[35] However, the slave trade did not become entrenched until the 17th century and Hawkins only embarked on 3 expeditions.

Blackamoor servants were perceived as a fashionable novelty and were popular in the homes of the wealthy, including that of Queen Elizabeth I.[37][38][35] Among these servants was 'John Come-quick, a blackemore', servant to Capt Thomas Love.[35] Others included in parish registers include Domingo "a black neigro servaunt unto Sir William Winter'', buried the xxviith daye of August [1587] and ‘Frauncis a Blackamoor servant to Thomas Parker’, buried in January 1591.[39] Some were free workers, although most were employed as servants and entertainers to the wealthy. Some worked in ports, but were invariably described as chattel labour.[40]

The black population may have been several hundred during the Elizabethan period, though their settlement was actively discouraged by Queen Elizabeth I.[41] Archival evidence shows records of more than 360 African people between 1500 to 1640 in England and Scotland.[42][43][44] Reacting to the darker complexion of people with biracial parentage, George Best argued in 1578 that black skin was not related to the heat of the sun (in Africa) but was instead caused by biblical damnation. Reginald Scot later associated black skin with witchcraft, describing (in his book Discoverie of Witchcraft) an unprepossessing devil in 1584 as having "horns on his head, fire in his mouth, a tail, eyes like a bison, fangs like a dog, claws like a bear, a skin like a niger and a voice roaring like a lion". These views existed across British society, including among playwrights and royalty, exemplified by the fact black slaves were used as some of the coach porters of King James VI of Scotland.[45][46] In part because they were generally not Christian, black people were seen as fundamentally different, and therefore common virtues did not so readily apply.[47] In addition, in this period, England had no concept of naturalization as a means of incorporating immigrants into the society. It conceived of English subjects as those people born on the island. Those who were not would never be considered subjects or citizens.[48]

In 1596, Queen Elizabeth I's privy council issued letters to the lord mayors of major cities asserting that "of late divers blackmoores brought into this realm, of which kind of people there are already here to manie..." Sir Thomas Sherley and Caspar Van Senden, a merchant of Lübeck, attempted to capitalise on this by petitioning Elizabeth I's Privy Council to allow them to transport slaves they had captured in Africa to Lisbon, presumably to sell them there. The relevant Privy Council Letters of July 1596 and a draft proclamation from the papers of Robert Cecil have been presented as an attempt to deport these captives from England.[49] However, Van Senden and Sherley did not succeed in this effort, as they acknowledged in correspondence with Sir Robert Cecil.[50] In 1601, Elizabeth issued another proclamation expressing her 'discontentment by the numbers of blackamores which are crept into this realm...' and again licensing van Senden to deport them. Her proclamation of 1601 stated that the blackamoors were 'fostered and relieved here to the great annoyance of [the queen's] own liege people, that want the relief, which those people consume'. It further stated that 'most of them are infidels, having no understanding of Christ or his Gospel'.[51]

Studies of blackamoors in early modern Britain indicate a minor continuing presence. Such studies include Imtiaz Habib's Black Lives in the English Archives, 1500–1677: Imprints of the Invisible,[52] (Ashgate, 2008), Onyeka's Blackamoores: Africans in Tudor England, Their Presence, Status and Origins[53] (Narrative Eye, 2013), and Miranda Kaufmann's Oxford DPhil thesis Africans in Britain, 1500–1640.[54]

17th and 18th centuries

The slave trade

At this time there was an increase in black settlement in London. Britain was involved with the tri-continental slave trade between Europe, Africa and the Americas. Black slaves were attendants to sea captains and ex-colonial officials, as well as traders, plantation owners and military personnel. This caused an increasing black presence in the northern, eastern, and southern areas of London. One of the most famous slaves to attend a sea captain was known as Sambo. He fell ill shortly after arriving in England and was consequently buried in Lancashire. His plaque and gravestone still stand to this day. There were also small numbers of free slaves and seamen from West Africa and South Asia. Many of these people were forced into beggary due to the lack of jobs and racial discrimination.[55][56]

The involvement of merchants from Great Britain[57] in the transatlantic slave trade was the most important factor in the development of the Black British community. These communities flourished in port cities strongly involved in the slave trade, such as Liverpool[57] and Bristol. By 1795, Liverpool had 62.5 per cent of the European Slave Trade.[57] As a result, Liverpool is home to Britain's oldest black community, dating at least to the 1730s. Some Liverpudlians are able to trace their black heritage in the city back ten generations.[57] Early black settlers in the city included seamen, the mixed-race children of traders sent to be educated in England, servants, and freed slaves. Mistaken references to slaves entering the country after 1722 being deemed to be free men are derived from a source in which 1722 is a misprint for 1772, in turn based on a misunderstanding of the results of the Somerset case referred to below.[58][59]

In 1787, Thomas Clarkson, an English abolitionist, noted at a speech in Manchester that "I was surprised also to find a great crowd of black people standing round the pulpit. There might be forty or fifty of them."[60] There is evidence that black men and women were occasionally discriminated against when dealing with the law because of their skin colour. In 1737, George Scipio was accused of stealing Anne Godfrey's washing, the case rested entirely on whether or not Scipio was the only black man in Hackney at the time.[61] Ignatius Sancho, black writer, composer, shopkeeper and voter in Westminster wrote, that despite being in Britain since the age of 2 he felt he was "only a lodger, and hardly that."[62] Sancho complained of "the national antipathy and prejudice" of native white Britons "towards their wooly headed brethren."[63] Sancho was frustrated that many resorted to stereotyping their black neighbours.[64] A financially-independent householder, he became the first black person of African origin to vote in parliamentary elections in Britain, in a time when only 3% of the British population were allowed to vote.[65]

In 1764, The Gentleman's Magazine reported that there was "supposed to be near 20,000 Negroe servants." It was reported in the Morning Gazette that there was 30,000 in the country as a whole, though the numbers were thought to be "alarmist" exaggerations. In the same year, a party for black men and women in a Fleet Street pub was sufficiently unusual to be written about in the newspapers. Their presence in the country was striking enough to start heated outbreaks of distaste for colonies of Hottentots.[66] Modern historians estimate, based on parish lists, baptismal and marriage registers as well as criminal and sales contracts, that about 10,000 black people lived in Britain during the 18th century.[67][68][69][70] Other estimates put the number at 15,000.[71][72][73] In 1772, Lord Mansfield put the number of black people in the country at as many as 15,000, though most modern historians consider 10,000 to be the most likely.[69][74] The black population was estimated at around 10,000 in London alone, making black people 1% of the overall London population.[75] The black female population is estimated to have barely reached 20% of the overall Afro-Caribbean population in the country.[75] In the 1780s with the end of the American Revolutionary War, hundreds of black loyalists from America were resettled in Britain.[76] Later some emigrated to Sierre Leonne with help from Committee for the Relief of the Black Poor after suffering destitution.[77]

Officially, slavery was never legal in England.[78] The Cartwright decision of 1569 resolved that England was "too pure an air for a slave to breathe in". However, black African slaves continued to be bought and sold in England during the eighteenth century.[79] The slavery issue was not legally contested until the Somerset case of 1772, which concerned James Somersett, a fugitive black slave from Virginia. Lord Chief Justice William Murray, 1st Earl of Mansfield concluded that Somerset could not be forced to leave England against his will. He later reiterated: ''The determinations go no further than that the master cannot by force compel him to go out of the kingdom.''[80] (See generally, Slavery at common law.) Despite the previous rulings, such as the 1706 declaration (which was clarified a year later) by Lord Chief Justice Holt[81] on slavery not being legal in Britain, it was often ignored, with the argument that the slaves were property and therefore could not be considered people.[82] Slave owner Thomas Papillon was one of many who took his black servant "to be in the nature and quality of my goods and chattel".[83][84] In 1731 the Lord Mayor of London ruled that ''no Negroes shall be bound apprentices to any Tradesman or Artificer of this City''. Due to this ruling, most were forced into working as servants.[85][86] Those black Londoners who were unpaid servants were in effect slaves in anything but name.[87]

Around the 1750s, London became the home of many Blacks, as well as Jews, Irish, Germans and Huguenots. According to Gretchen Gerzina in her Black London, by the mid-18th century, Blacks comprised somewhere between one and three per cent of the London populace.[88][89] Evidence of the number of Black residents in the city has been found through registered burials. Some black people in London resisted slavery through escape.[88] Leading Black activists of this era included Olaudah Equiano, Ignatius Sancho and Quobna Ottobah Cugoano.

With the support of other Britons, these activists demanded that Blacks be freed from slavery. Supporters involved in these movements included workers and other nationalities of the urban poor. London Blacks vocally contested slavery and the slave trade. At this time, the slavery of whites was forbidden, but the legal statuses of these practices were not clearly defined.

During this era, Lord Mansfield declared that a slave who fled from his master could not be taken by force in England, nor sold abroad. Mansfield was at pains to point out that his ruling did not abolish slavery itself in eighteenth century England.[90] This verdict fuelled the numbers of Blacks who escaped slavery, and helped send slavery into decline. During this same period, many former American slave soldiers, who had fought on the side of the British in the American Revolutionary War, were resettled as free men in London. They were never awarded pensions, and many of them became poverty-stricken and were reduced to begging on the streets. Reports at the time stated they: ''had no prospect of subsisting in this country but by depredations on the public, or by common charity.'' A sympathetic observer wrote that ''great numbers of Blacks and People of Colour, many of them refugees from America and others who have by land or sea been in his Majesty's service were.....in great distress.'' Even towards white loyalists there was little good will to new arrivals from America.[91]

The blacks in London lived among whites in areas of Mile End, Stepney, Paddington, and St Giles. After Mansfield's ruling many former slaves continued to work for their old masters as paid employees. Between 14,000 and 15,000 (then contemporary estimates) slaves were immediately freed in England.[92] Many of these emancipated individuals became labelled as the "black poor", the black poor were defined as former slave soldiers since emancipated, seafarers, such as South Asian lascars,[93] former indentured servants and former indentured plantation workers.[94]

During the late 18th century, numerous publications and memoirs were written about the "black poor". One example is the writings of Equiano, a former slave who became an unofficial spokesman for Britain's Black community. His memoir about his life entitled The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano.

In 1786, Olaudah Equiano became the first black person to be employed by the British government, when he was made Commissary of Provisions and Stores for the 350 black people suffering from poverty who had decided to accept the government's offer of an assisted passage to Sierra Leone.[95] The following year, in 1787, encouraged by the Committee for the Relief of the Black Poor, 4,000[96] black Londoners were aided in emigrating to Sierra Leone in West Africa, founding the first British colony on the continent.[97] They asked that their status as British subjects be recognized, along with the duty of the Royal Navy to defend them. It is possible a desire to remove black people from London[2] was a principal goal of the committee. There was a prevalent view among the contemporary British West Indian plantocracy that racial intermarriage was abhorrent. The chair of the committee wrote to the Standing Committee of West India Planters and Merchants requesting their advice and assistance in procuring an act of parliament to "prevent any Foreign Blacks being brought to this country to remain".[98]

An Indian Briton, Dadabhai Naoroji, stood for election to parliament for the Liberal Party in 1886. He was defeated, leading the leader of the Conservative Party, Lord Salisbury to remark that "however great the progress of mankind has been, and however far we have advanced in overcoming prejudices, I doubt if we have yet got to the point of view where a British constituency would elect a Blackman".[99] This led to much discussion about the applicability of the term "black" to South Asians. Naoroji was elected to parliament in 1892, becoming the first Member of Parliament (MP) of Indian descent.

19th century

In the late 18th century, the British slave trade declined in response to changing popular opinion. Both Great Britain and the United States abolished the Atlantic slave trade in 1808, and cooperated in liberating slaves from illegal trading ships off the coast of West Africa. Many of these freed slaves were taken to Sierra Leone for settlement. Slavery was abolished completely in the British Empire by 1834, although it had been profitable on Caribbean plantations. Fewer blacks were brought into London from the West Indies and West Africa.[94] The resident British black population, primarily male, was no longer growing from the trickle of slaves and servants from the West Indies and America.[100] Abolition meant a virtual halt to the arrival of black people to Britain, just as immigration from Europe was increasing.[101] The black population of Victorian Britain was so small that those living outside of larger trading ports were isolated from the black population.[102][103] The mentioning of black people and descendants in parish registers declined markedly in the early 19th century. It is possible that researchers simply did not collect the data or that the mostly black male population of the late 18th century had married white women.[104][105] Evidence of such marriages may still be found today with descendants of black servants such as Francis Barber, a Jamaican-born servant who lived in Britain during the 18th century. His descendants still live in England today and are white.[106] Abolition of slavery in 1833, effectively ended the period of small-scale black immigration to London and Britain. Though, there were some exceptions, black and Chinese seamen began putting down the roots of small communities in British ports, not least because they were abandoned there by their employers.[101]

By the late 19th century, race discrimination was fed by theories of scientific racism, which held that whites were the superior race and that blacks were less intelligent than whites. Attempts to support these theories cited 'scientific evidence', such as brain size. James Hunt, President of the London Anthropological Society, in 1863 in his paper "On the Negro's place in nature" wrote,"the Negro is inferior intellectually to the European...[and] can only be humanised and civilised by Europeans.''[107] In the 1880s, there was a build-up of small groups of black dockside communities in towns such as Canning Town,[108] Liverpool and Cardiff. This was a direct effect of new shipping links that were established with the Caribbean and West Africa.

_(cropped).jpg)

Despite social prejudice and discrimination in Victorian England, some 19th-century black Britons achieved exceptional success. Pablo Fanque, born poor as William Darby in Norwich, rose to become the proprietor of one of Britain's most successful Victorian circuses. He is immortalised in the lyrics of The Beatles song "Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite!" Thirty years after his 1871 death, the chaplain of the Showman's Guild said:

"In the great brotherhood of the equestrian world there is no colour line [bar], for, although Pablo Fanque was of African extraction, he speedily made his way to the top of his profession. The camaraderie of the ring has but one test – ability."[109]

Another great circus performer was equestrian Joseph Hillier, who took over and ran Andrew Ducrow's circus company after he died.[110]

Early 20th century

World War I

World War I saw a small growth in the size of London's Black communities with the arrival of merchant seamen and soldiers. At that time, there were also small groups of students from Africa and the Caribbean migrating into London. These communities are now among the oldest black communities of London.[111] The largest Black communities were to be found in the United Kingdom's great port cities: London's East End, Liverpool, Bristol and Cardiff's Tiger Bay, with other communities in South Shields in Tyne & Wear and Glasgow. In 1914, the black population was estimated at 10,000 and centered largely in London, with around 70% being men.[112] These residents had for the most part emigrated from parts of the British Empire. The number of black soldiers serving in the British army prior to World War I is unknown, but was likely to have been negligibly low.[112] One of the Black British soldiers during World War I was Walter Tull, an English professional footballer, born to a Barbadian carpenter Daniel Tull and Kent-born Alice Elizabeth Palmer. His grandfather was a slave in Barbados.[113] Tull became the first British-born mixed-heritage infantry officer in a regular British Army regiment, despite the 1914 Manual of Military Law specifically excluding soldiers that were not 'of pure European descent' from becoming commissioned officers.[114][115][116]

Colonial soldiers and sailors of Afro-Caribbean descent served here during the war and some settled in these cities. The South Shields community—which also included other "coloured" seamen known as lascars, who were from South Asia and the Arab world—were victims of the UK's first race riot in 1919.[117] Soon eight other cities with significant non-white communities were also hit by race riots.[118] Due to these disturbances, many of the residents from the Arab world as well as some other immigrants were evacuated to their homelands.[119] In that first postwar summer, other racial riots of whites against "coloured" peoples also took place in numerous United States cities, towns in the Caribbean, and South Africa.[118] They were part of the social dislocation after the war as societies struggled to integrate veterans into the work forces again, and groups competed for jobs and housing. At Australian insistence, the British refused to accept the Racial Equality Proposal put forward by the Japanese at the Paris Peace Conference, 1919.

World War II

World War II marked another period of growth for the black communities in London, Liverpool and elsewhere in Britain. Many blacks from the Caribbean and West Africa arrived in small groups as wartime workers, merchant seamen, and servicemen from the army, navy, and air forces.[120] For example, in February 1941, 345 West Indians came to work in factories in and around Liverpool, making munitions.[121] By the end of 1943 there were 3,312 African-American GIs based at Maghull and Huyton, near Liverpool.[122] The black population in the summer of 1944 was estimated at 150,000 comprising mostly black GIs from America. However, by 1948 the black population was estimated to have been less than 20,000 and did not reach the previous peak of 1944 until 1958.[123]

Learie Constantine, a West Indian cricketer, was a welfare officer with the Ministry of Labour when he was refused service at a London hotel. He sued for breach of contract and was awarded damages. This particular example is used by some to illustrate the slow change from racism towards acceptance and equality of all citizens in London.[124]

Post-war

In 1950 there were probably fewer than 20,000 non-white residents in Britain, almost all born overseas.[125] After World War II, the largest influx of Black people occurred, mostly from the British West Indies. Over a quarter of a million West Indians, the overwhelming majority of them from Jamaica, settled in Britain in less than a decade. In 1951 the population of Caribbean and African-born people in Britain was estimated at 20,900.[126] In the mid-1960s, Britain had become the centre of the largest overseas population of West Indians.[127] This migration event is often labelled "Windrush", a reference to the HMT Empire Windrush, the ship that carried the first major group of Caribbean migrants to the United Kingdom in 1948.[128]

"Caribbean" is itself not one ethnic or political identity; for example, some of this wave of immigrants were Indo-Caribbean. The most widely used term used at that time was "West Indian" (or sometimes "coloured"). "Black British" did not come into widespread use until the second generation were born to these post-war migrants to the UK. Although British by nationality, due to friction between them and the white majority they were often born into communities that were relatively closed, creating the roots of what would become a distinct Black British identity. By the 1950s, there was a consciousness of black people as a separate group that had not been there between 1932 and 1938.[127] The increasing consciousness of Black British peoples was deeply informed by the influx of Black American culture imported by Black servicemen during and after World War II, music being a central example of what Jacqueline Nassy-Brown calls "diasporic resources". These close interactions between Americans and Black British were not only material but also inspired the expatriation of some Black British women to America after marrying servicemen (some of whom later repatriated to the UK).[129]

Late 20th century

In 1961, the Black British population was estimated at 191,600, just under 0.4% of the total UK population.[126] The 1962 Commonwealth Immigrants Act was passed in Britain along with a succession of other laws in 1968, 1971 and 1981, which severely restricted the entry of Black immigrants into Britain. During this period it is widely argued that emergent blacks and Asians struggled in Britain against racism and prejudice. During the 1970s—and partly in response to both the rise in racial intolerance and the rise of the Black Power movement abroad—"black" became detached from its negative connotations, and was reclaimed as a marker of pride: black is beautiful.[127] In 1975, David Pitt was appointed to the House of Lords. He spoke against racism and for equality in regards to all residents of Britain. In the years that followed, several Black members were elected into the British Parliament. By 1981, the black population in the United Kingdom was estimated at 1.2% of all countries of birth, comprising 0.8% Black-Caribbean, 0.3% Black-Other, and 0.1% Black-African residents.[130]

Since the 1980s, the majority of black immigrants into the country have come directly from Africa, in particular, Nigeria and Ghana in West Africa, Uganda and Kenya in East Africa, Zimbabwe, and South Africa in Southern Africa. Nigerians and Ghanaians have been especially quick to accustom themselves to British life, with young Nigerians and Ghanaians achieving some of the best results at GCSE and A-Level, often on a par or above the performance of white pupils.[131] The rate of inter-racial marriage between British citizens born in Africa and native Britons is still fairly low, compared to those from the Caribbean. This might change over time as Africans become more part of mainstream British culture as second and third generation African communities become established.

By the end of the 20th century the number of black Londoners numbered half a million, according to the 1991 census. The 1991 census was the first to include a question on ethnicity, and the black population of Great Britain (i.e. the United Kingdom excluding Northern Ireland, where the question was not asked) was recorded as 890,727, or 1.63% of the total population. This figure included 499,964 people in the Black-Caribbean category (0.9%), 212,362 in the Black-African category (0.4%) and 178,401 in the Black-Other category (0.3%).[132][133] An increasing number of black Londoners were London- or British-born. Even with this growing population and the first blacks elected to Parliament, many argue that there was still discrimination and a socio-economic imbalance in London among the blacks. In 1992, the number of blacks in Parliament increased to six, and in 1997, they increased their numbers to nine. There are still many problems that black Londoners face; the new global and high-tech information revolution is changing the urban economy and some argue that it is driving up unemployment rates among blacks relative to non-blacks,[94] something, it is argued, that threatens to erode the progress made thus far.[94] By 2001, the Black British population was estimated at 1,148,738 (2.0%).[134]

Street conflicts and policing

The late 1950s through to the late 1980s saw a number of mass street conflicts involving young Afro-Caribbean men and (largely white) British police officers in English cities, mostly as a result of tensions between members of local black communities and white racists.

The first major incident occurred in 1958 in Notting Hill, when roaming gangs of between 300 and 400 white youths attacked Afro-Caribbeans and their houses across the neighbourhood, leading to a number of Afro-Caribbean men being left unconscious in the streets.[135] The following year, Antigua-born Kelso Cochrane died after being set upon and stabbed by a gang of white youths while walking home to Notting Hill.

During the 1970s, police forces across England increasingly began to use the Sus law, provoking a sense that young black men were being discriminated against by the police[136] The next newsworthy outbreak of street fighting occurred in 1976 at the Notting Hill Carnival when several hundred police officers and youths became involved in televised fights and scuffles, with stones thrown at police, baton charges and a number of minor injuries and arrests.[137]

The 1980 St. Pauls riot in Bristol saw fighting between local youths and police officers, resulting in numerous minor injuries, damage to property and arrests. In London 1981 brought further conflict, with a perceived racist police force after the death of 13 black youngsters who were attending a birthday party that ended in the devastating New Cross Fire. The fire was viewed by many as a racist massacre[135] and a major political demonstration, known as the Black People's Day of Action was held to protest against the attacks themselves, a perceived rise in racism, and perceived hostility and indifference from the police, politicians and media.[135] Tensions were further inflamed when, in nearby Brixton, police launched operation Swamp 81, a series of mass stop-and-searches of young black men.[135] Anger erupted when up to 500 people were involved in street fighting between the Metropolitan Police and local Afro-Caribbean community, leading to a number of cars and shops set on fire, stones thrown at police and hundreds of arrests and minor injuries. A similar pattern occurred further north in Toxteth, Liverpool, and Chapeltown, Leeds.[138]

Despite the recommendations of the Scarman Report (published in November 1981),[135] relations between black youths and police did not significantly improve and a further wave of nationwide conflicts occurred in Handsworth, Birmingham, in 1985, when the local South Asian community also became involved.[136] Following the police shooting of a black grandmother Cherry Groce in Brixton, and the death of Cynthia Jarrett during a raid on her home in Tottenham, in north London, protests held at the local police stations did not end peacefully and further street battles with the police erupted,[135] the disturbances later spreading to Manchester's Moss Side.[135] The street battles themselves (involving more stone-throwing, the discharge of one firearm, and several fires) led to two fatalities (in the Broadwater Farm riot) and Brixton.

In 1999, following the Macpherson Inquiry into the 1993 killing of Stephen Lawrence, Sir Paul Condon, commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, accepted that his organisation was institutionally racist. Some members of the Black British community were involved in the 2001 Harehills race riot and 2005 Birmingham race riots.

Early 21st century

In 2011, following the shooting of a mixed-race man, Mark Duggan, by police in Tottenham, a protest was held at the local police station. The protest ended with an outbreak of fighting between local youths and police officers leading to widespread disturbances across English cities.

Some analysts claimed that black people were disproportionally represented in the 2011 England riots.[139] Research suggests that race relations in Britain deteriorated in the period following the riots and that prejudice towards ethnic minorities increased.[140] Groups such as the EDL and the BNP were said to be exploiting the situation.[141] Racial tensions between blacks and Asians in Birmingham increased after the deaths of three Asian men at the hands of a black youth.[142]

In a Newsnight discussion on 12 August 2011, historian David Starkey blamed black gangster and rap culture, saying that it had influenced youths of all races.[143] Figures showed that 46 per cent of people brought before a courtroom for arrests related to the 2011 riots were black.[144]

Demographics

Population

The 2011 UK Census recorded 1,904,684 residents who identified as "Black/African/Caribbean/Black British", accounting for 3 per cent of the total UK population.[1] This was the first UK census where the number of self-reported Black African residents exceeded that of Black Caribbeans.[145]

Within England and Wales, 989,628 individuals specified their ethnicity as "Black African", 594,825 as "Black Caribbean", and 280,437 as "Other Black".[146] In Northern Ireland, 2,345 individuals self-reported as "Black African", 372 as "Black Caribbean", and 899 as "Other Black", totaling 3,616 "Black" residents.[147] In Scotland, 29,638 persons identified themselves as "African", choosing either the "African, African Scottish or African British" tick box or the "Other African" tick box and write-in area. 6,540 individuals also self-reported as "Caribbean or Black", selecting either the "Caribbean, Caribbean Scottish or Caribbean British" tick box, the "Black, Black Scottish or Black British" tick box, or the "Other Caribbean or Black" tick box and write-in area.[148] In order to compare UK-wide results, the Office for National Statistics combined the "African" and "Caribbean or Black" entries at the top-level,[17] and reported a total of 36,178 "Black" residents in Scotland.[1] According to the ONS, individuals in Scotland with "Other African", "White" and "Asian" ethnicities as well as "Black" identities could thus all potentially be captured within this combined output.[17] The General Register Office for Scotland, which devised the categories and administers the Scotland census, does not combine the "African" and "Caribbean or Black" entries, maintaining them as separate for individuals who do not self-identify as "Black" (see census classification).[19]

In the 2001 Census, 565,876 people in the United Kingdom had reported their ethnicity as "Black Caribbean", 485,277 as "Black African", and 97,585 as "Black Other", making a total of 1,148,738 "Black or Black British" residents. This was equivalent to 2 per cent of the UK population at the time.[134]

Population distribution

Most Black Britons can be found in the large cities and metropolitan areas of the country. The 2011 census found that 1.85 million of a total Black population of 1.9 million lived in England, with 1.09 million of those in London, where they made up 13.3 per cent of the population, compared to 3.5 per cent of England's population and 3 per cent of the UK's population. The ten local authorities with the highest proportion of their populations describing themselves as Black in the census were all in London: Lewisham (27.2 per cent), Southwark (26.9 per cent), Lambeth (25.9 per cent), Hackney (23.1 per cent), Croydon (20.2 per cent), Barking and Dagenham (20.0 per cent), Newham (19.6 per cent), Greenwich (19.1 per cent), Haringey (18.8 per cent) and Brent (18.8 per cent).[1]

Mixed marriages

An academic journal article published in 2005, citing sources from 1997 and 2001, estimated that nearly half of British-born African-Caribbean men, a third of British-born African-Caribbean women, and a fifth of African men, have white partners.[149] In 2014, The Economist reported that, according to the Labour Force Survey, 48 per cent of black Caribbean men and 34 per cent of black Caribbean women in couples have partners from a different ethnic group. Moreover, mixed-race children under the age of ten with black Caribbean and white parents outnumber black Caribbean children by two-to-one.[150]

Culture and community

Dialect

British Black English is a variety of the English language spoken by a large number of the Black British population of Afro-Caribbean ancestry.[151] British Black dialect has been influenced by Jamaican Patois owing to the large number of immigrants from Jamaica, but it is also spoken or imitated by those of different ancestry.

British Black speech is also heavily influenced by social class and the regional dialect (Cockney, Mancunian, Brummie, Scouse, etc.).

Music

Black British music is a long-established and influential part of British music. Its presence in the United Kingdom stretches back to the 18th century, encompassing concert performers such as George Bridgetower and street musicians the like of Billy Waters. Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1875–1912) achieved great success as a composer at the end of the 19th and early 20th centuries.

In the late 1970s and 1980s, 2 Tone became popular with the British youth; especially in the West Midlands. A blend of punk, ska and pop made it a favourite among both white and black audiences. Famous bands in the genre include The Selecter, The Specials, The Beat and The Bodysnatchers.

Jungle, dubstep, drum and bass, UK garage and grime music were invented in London and involve a number of artists from primarily Caribbean communities but recently Black Africans also, most notably of Ghanaian and Nigerian origin. Famous grime artists include Dizzee Rascal, Tinchy Stryder, Tinie Tempah, Chipmunk, Kano (rapper), Wiley and Lethal Bizzle. It is now common to hear British MCs rapping in a strong London accent. Niche, with its origin in Sheffield and Leeds, has a much faster bassline and is often sung in a northern accent. Famous niche artists include producer T2.

The MOBO Awards – recognizing performers of "Music of Black Origin" – are seen as a UK equivalent to the BET Awards and Soul Train Awards for being the main award show in Britain to focus on urban music.

Media

The black community in Britain has a number of leading publications. First, the key publication is The Voice newspaper. Founded by Val McCalla in 1982, The Voice newspaper is Britain's only national Black weekly newspaper. The newspaper primarily targets the Caribbean diaspora and has been printed for more than 35 years.[152] Second, the Black History Month magazine is a central point of focus which leads the nationwide celebration of Black History, Arts and Culture throughout the UK.[153] Third, Pride Magazine is the largest monthly magazine which targets black British, mixed race, African and African-Caribbean women in the United Kingdom. Pride magazine has been in print since 1991. In 2007, The Guardian reported that the magazine had dominated the black women's magazine market for over 15 years.[154] Its owner, Pride Media, also specialises in helping organisations target this fast-growing community through a range of media. Fourth, Keep The Faith magazine is Britain's leading and multi-award winning Black and minority ethnic community magazine. Keep The Faith is a quarterly magazine which has been in print since 2005.[155] Keep The Faith’s editorial contributors are some of the most powerful and influential movers and shakers, and successful entrepreneurs within BME communities.

Many major Black British publications are handled through Diverse Media Group.[156] Diverse Media Group specialises in helping organisations reach Britain's Black and minority ethnic community through the main media they consume. The senior leadership team is an composite of many CEO and owners from the publications listed above.

The community also has a number of radio stations and cable-television channels targeting them.

Social issues

There is much controversy surrounding the politics of integrating the United Kingdom's black community, particularly concerning institutional racism and inequality present in the employment and higher education of urban black Britons.

Racism

The wave of black immigrants who arrived in Britain from the Caribbean in the 1950s faced significant amounts of racism. For many Caribbean immigrants, their first experience of discrimination came when trying to find private accommodation. They were generally ineligible for council housing because only people who had been resident in the UK for a minimum of five years qualified for it. At the time, there was no anti-discrimination legislation to prevent landlords from refusing to accept black tenants. A survey undertaken in Birmingham in 1956 found that only 15 of a total of 1,000 white people surveyed would let a room to a black tenant. As a result, many black immigrants were forced to live in slum areas of cities, where the housing was of poor quality and there were problems of crime, violence and prostitution.[157][158] One of the most notorious slum landlords was Peter Rachman, who owned around 100 properties in the Notting Hill area of London. Black tenants typically paid twice the rent of white tenants, and lived in conditions of extreme overcrowding.[157]

Historian Winston James argues that the experience of racism in Britain was a major factor in the development of a shared Caribbean identity amongst black immigrants from a range of different island and class backgrounds.[159]

In the 1970s and 1980s, black people in Britain were the victims of racist violence perpetrated by far-right groups such as the National Front.[160] During this period, it was also common for Black footballers to be subjected to racist chanting from crowd members.[161][162]

Racism in Britain in general, including against black people, is considered to have declined over time. Academic Robert Ford demonstrates that social distance, measured using questions from the British Social Attitudes survey about whether people would mind having an ethnic minority boss or have a close relative marry an ethnic minority spouse, declined over the period 1983–1996. These declines were observed for attitudes towards Black and Asian ethnic minorities. Much of this change in attitudes happened in the 1990s. In the 1980s, opposition to interracial marriage were significant.[163][164] Nonetheless, Ford argues that "Racism and racial discrimination remain a part of everyday life for Britain's ethnic minorities. Black and Asian Britons...are less likely to be employed and are more likely to work in worse jobs, live in worse houses and suffer worse health than White Britons".[163] The University of Maryland's Minorities at Risk (MAR) project noted in 2006 that while African-Caribbeans in the United Kingdom no longer face formal discrimination, they continue to be under-represented in politics, and to face discriminatory barriers in access to housing and in employment practices. The project also notes that the British school system "has been indicted on numerous occasions for racism, and for undermining the self-confidence of black children and maligning the culture of their parents". The MAR profile on African-Caribbeans in the United Kingdom notes "growing 'black on black' violence between people from the Caribbean and immigrants from Africa".[165]

There is concern that murders using knives are given insufficient attention because most victims are black. Martin Hewitt of the Metropolitan Police said, “I do fear sometimes that because the majority of those that are injured or killed are coming from certain communities and very often the black communities in London, it doesn’t get the sense of collective outrage that it ought to do and really get everyone to a place where we are all doing everything we can to prevent this from happening. It’s an enormous effort on our part. We are putting enormous resources in to try and stem the flow of the violence and having some success at doing that. But collectively we all ought to be looking at this and seeing how we can prevent it.”[166][167]

Unemployment

According to the 2005 TUC report Black workers, jobs and poverty, Black and minority ethnic people (BMEs) were far more likely to be unemployed than the white population. The rate of unemployment among the white population was only 12%, but among black groups it was 16%, mixed-race 15%, Indian 7%, Pakistani 15%, Bangladeshi 17% and Chinese 5%. The rates of poverty and low income were twice to three times higher, of the different ethnic groups studied, Bangladeshis, Pakistanis and Black British had the highest rates of child poverty of over 50%.[168]

A 2014 study by the Black Training and Enterprise Group (BTEG), funded by Trust for London, explored the views of young Black males in London on why their demographic have a higher unemployment rate than any other group of young people, finding that many young black men in London believe that racism and negative stereotyping are the main reasons for their high unemployment rate.[169]

Crime

Both racist crime and gang-related crime continues to affect black communities, so much so that the Metropolitan Police launched Operation Trident to tackle black-on-black crimes. Numerous deaths in police custody of black men has generated a general distrust of police among urban blacks in the UK.[170][171] According to the Metropolitan Police Authority in 2002–03 of the 17 deaths in police custody, 10 were black or Asian – black convicts have a disproportionately higher rate of incarceration than other ethnicities. The government reports[172] The overall number of racist incidents recorded by the police rose by 7 per cent from 49,078 in 2002/3 to 52,694 in 2003/4.

Media representation of young black British people has focused particularly on "gangs" with black members and violent crimes involving black victims and perpetrators.[173] According to a Home Office report,[172] 10 per cent of all murder victims between 2000 and 2004 were black. Of these, 56 per cent were murdered by other black people (with 44 per cent of black people murdered by whites and Asians – making black people disproportionately higher victims of killing by people from other ethnicities). In addition, a Freedom of Information request made by The Daily Telegraph shows internal police data that provides a breakdown of the ethnicity of the 18,091 men and boys who police took action against for a range of offences in London in October 2009. Among those proceeded against for street crimes, 54 per cent were black; for robbery, 59 per cent; and for gun crimes, 67 per cent.[174]

Black people, who according to government statistics[175] make up 2 per cent of the population, are the principal suspects in 11.7 per cent of murders, i.e. in 252 out of 2163 murders committed 2001/2, 2002/3, and 2003/4.[176] It should be noted that, judging on the basis of prison population, a substantial minority (about 35%) of black criminals in the United Kingdom are not British citizens but foreign nationals.[177] In November 2009, the Home Office published a study that showed that, once other variables had been accounted for, ethnicity was not a significant predictor of offending, anti-social behaviour or drug abuse among young people.[178]

After several high-profile investigations such as that of the murder of Stephen Lawrence, the police have been accused of racism, from both within and outside the service. Cressida Dick, head of the Metropolitan Police's anti-racism unit in 2003, remarked that it was "difficult to imagine a situation where we will say we are no longer institutionally racist".[179] Black people were seven times more likely to be stopped and searched by police compared to white people, according to the Home Office, A separate study said blacks were more than nine times more likely to be searched.[180]

Even though blacks are only 2 to 3% of the general UK population, black prisoners make up 15% of the British prison population, which experts say is "a result of decades of racial prejudice in the criminal justice system and an overly punitive approach to penal affairs."[181]

Notable black Britons

Pre-20th century

Well-known black Britons living before the 20th century include the Chartist William Cuffay; William Davidson, who was executed as a Cato Street conspirator; Olaudah Equiano (also called Gustavus Vassa), a former slave who bought his freedom, moved to England, and settled in Soham, Cambridgeshire, where he married and wrote an autobiography, dying in 1797; Ukawsaw Gronniosaw, pioneer of the slave narrative; and Ignatius Sancho, a grocer who also acquired a reputation as a man of letters.

In 2004, a poll found that people considered the Crimean War heroine Mary Seacole to be the greatest Black Briton.[182] Seacole was born in Jamaica in 1805 to a white father and black mother.[183] A statue of her, designed by Martin Jennings, was unveiled in the grounds of St. Thomas' Hospital opposite the Houses of Parliament in London in June 2016, following a 12-year campaign that raised £500,000 to honour her.[184]

Television

Television reporter and newsreader Sir Trevor McDonald, born in Trinidad, was knighted in 1999. Also notable is Moira Stuart, OBE, the first female newsreader of African-Caribbean heritage on British television. Other high-profile television personalities and entertainers include Lenny Henry and chef Ainsley Harriott.

Singers

Billy Ocean, Eddy Grant, Shirley Bassey, Seal, Simon Webbe, Joan Armatrading, Jaki Graham, Sade, Leona Lewis, Maxine Nightingale and Benji Webbe are among the popular singers not mentioned in the music section above.

Film

Initially receiving acclaim as a visual artist and winning the Turner Prize in 1999, Steve McQueen went on to direct his first feature Hunger (2008), which earned him the Caméra d'Or at the 2008 Cannes Film Festival. His most recent film, 12 Years a Slave (2013), won several major international awards, and McQueen is the first black filmmaker to win an Academy Award for Best Picture.[185]

Actors

Numerous Black British actors have become successful in US television, such as Adewale Akinnuoye-Agbaje, Idris Elba, Lennie James, Marsha Thomason and Marianne Jean-Baptiste. Black British actors are also increasingly found starring in major Hollywood movies, notable examples include Adrian Lester, Antonia Thomas, Ashley Walters, Chiwetel Ejiofor, Colin Salmon, Daniel Kaluuya, David Harewood, David Oyelowo, Delroy Lindo, Eamonn Walker, Franz Drameh, Gugu Mbatha-Raw, Hugh Quarshie, John Boyega, Maisie Richardson-Sellers, Naomie Harris, Sophie Okonedo, Eunice Olumide and Thandie Newton.

Visual artists

Among notable Black British visual artists are painters such as Chris Ofili, Frank Bowling, Keith Piper, Sonia Boyce, Paul Dash, Kimathi Donkor, Claudette Johnson, Winston Branch, and sculptors including Sokari Douglas Camp, Ronald Moody, Fowokan, Yinka Shonibare and Zak Ové.

Writers

Notable Black British writers include novelists Caryl Phillips, Zadie Smith, Andrea Levy (whose 2004 book Small Island won the Whitbread Book of the Year, the Orange Prize for Fiction and the Commonwealth Writers' Prize), Bernardine Evaristo, Alex Wheatle, Ferdinand Dennis (winner of the Martin Luther King Memorial Prize for his 1988 travelogue Behind the Frontlines: Journey into Afro-Britain), Mike Phillips and Diran Adebayo (first winner in 1995 of the Saga Prize, which was set up by Marsha Hunt to encourage Black British writing and ran for four years),[186] poets Benjamin Zephaniah, Linton Kwesi Johnson, Lemn Sissay, Salena Godden and Patience Agbabi, playwrights Mustapha Matura, Kwame Kwei-Armah, Roy Williams, Winsome Pinnock, Patricia Cumper and Bola Agbaje, journalists such as Gary Younge and Ekow Eshun, and Children's Laureate Malorie Blackman. Onyeka Nubia is the author of fictional trilogy Waiting to Explode, The Black Prince, and The Phoenix, for which he won the 2009 African Achievers award for Communication and Media. Blackamoores: Africans in Tudor England, their Presence, Status and Origins is his latest book, published by Narrative Eye[187] in 2013, in which he proves that Black people in Tudor England had free status and were not slaves. Blackamoores was runner-up in the 2013/14 People's Book Prize.[188]

Police service

Michael Fuller, after a career in the Metropolitan Police, served as the Chief Constable of Kent 2004-2010. He is the son of Jamaican immigrants who came to the United Kingdom in the 1950s. Fuller was brought up in Sussex, where his interest in the police force was encouraged by an officer attached to his school. He is a graduate in social psychology.[189]

Military services

In 2005, soldier Johnson Beharry, born in Grenada, became the first man to win the Victoria Cross, the United Kingdom's foremost military award for bravery, since the Falklands War of 1982. He was awarded the medal for service in Iraq in 2004.

Sport

In sport, prominent examples of success include boxing champion Frank Bruno, whose career highlight was winning the WBC world heavyweight championship in 1995. Altogether, he has won 40 of his 45 contests. He is also well known for acting in pantomime. Lennox Lewis, born in east London, is another successful Black British boxer and former undisputed heavyweight champion of the world.

There are many notable black British footballers, some of whom have played for England, including Paul Ince, Sol Campbell, John Barnes, Rio Ferdinand, Viv Anderson, Des Walker, Ashley Cole, Ian Wright, Daniel Sturridge, Daniel Welbeck, Raheem Sterling, Jesse Lingard, Danny Rose, Ryan Bertrand, Kyle Walker, Dele Alli and David James. Andrew Watson who is widely considered to be the world's first association footballer of black heritage, Chris Iwelumo, Jai Quitongo and Zak Jules have all played for Scotland. Eddie Parris, Danny Gabbidon, Nathan Blake and Ashley Williams have played for Wales.

Black British people have performed well in track and field. Daley Thompson was the gold medallist for the Great Britain team in the decathlon in the 1980 and 1984 Olympics. The most decorated British athlete is Jamaica-born Linford Christie, who moved to the United Kingdom at age seven. He was winner of the gold medal in the 100 meters at the 1992 Olympics, the World Championships, the European Championships and the Commonwealth Games. Sprinter Dwain Chambers grew up in London. His early achievements winning a world junior record for the 100 meters in 1997, as the youngest medal winner in the 1999 world championships, and fourth place at the 2000 Olympics were marred by a later scandal over the use of performance-enhancing drugs, like Christie before him. Kelly Holmes won Olympic gold in both the 800m and 1500m, and set many British records.

In cricket, many have represented England: Devon Malcolm, Phillip DeFreitas, Chris Lewis, Gladstone Small, Dean Headley, Alex Tudor, Michael Carberry and Chris Jordan to name a few.

In Formula 1, the highest rank of motorsport sanctioned by the FIA, Lewis Hamilton from Stevenage is the current world champion, having also won the championship in 2008, 2014 and 2015. With four titles and over 60 wins and 65 pole positions, he is the most decorated and successful driver in British history.

Business

In business, Damon Buffini heads Permira, one of the world's largest private equity firms. He topped the 2007 "power list" as the most powerful Black male in the United Kingdom by New Nation magazine and was appointed to then Prime Minister Gordon Brown's business advisory panel.

René Carayol is a broadcaster, broadsheet columnist, business and leadership speaker and author, best known for presenting the BBC series Did They Pay Off Their Mortgage in Two Years? He has also served as an executive main board director for blue-chip companies as well as the public sector.

Wol Kolade is council member and Chairman of the BVCA (British Venture Capital Association) and a Governor and council member of the London School of Economics and Political Science, chairing its Audit Committee.

Adam Afriyie is a politician, and Conservative Member of Parliament for Windsor. He is also the founding director of Connect Support Services, an IT services company pioneering fixed-price support. He was also Chairman of DeHavilland Information Services plc, a news and information services company, and was a regional finalist in the 2003 Ernst and Young Entrepreneur of the year awards.

Wilfred Emmanuel-Jones is a businessman, farmer and founder of the popular Black Farmer range of food products. He stood, unsuccessfully, as Conservative Party candidate for the Chippenham constituency in the 2010 general election.

Houses of Parliament

People of black African ancestry such as Bernie Grant, Baroness Amos, David Lammy and Diane Abbott, as well as Oona King and Paul Boateng who are of mixed race, have made significant contributions to British politics and trade unionism. Boateng became the United Kingdom's first biracial cabinet minister in 2002 when he was appointed as Chief Secretary to the Treasury. Abbott became the first black woman Member of Parliament when she was elected to the House of Commons in the 1987 general election.

Bill Morris was elected general secretary of the Transport and General Workers' Union in 1992. He was knighted in 2003, and in 2006 he took a seat in the House of Lords as a working life peer, Baron Morris of Handsworth.

The Trinidadian cricketer Learie Constantine was ennobled in 1969 and took the title Baron Constantine of Maraval in Trinidad and Nelson in the County Palatine of Lancaster.

David Pitt became a member of the House of Lords when he became a Life Peer for the Labour Party in 1975. He was also President of the British Medical Association. The first black Conservative Peer was John Taylor, Baron Taylor of Warwick.[190] Valerie Amos became the first black woman cabinet minister and the first black woman to become leader of the House of Lords.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 "2011 Census: Ethnic group, local authorities in the United Kingdom". Office for National Statistics. 11 October 2013. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- ↑ "Table KS201SC – Ethnic group: All people" (PDF). National Records of Scotland. 2013. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- ↑ "Ethnic group". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ↑ "Ethnic group: By religion, April 2011, Great Britain". Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original on 14 November 2010. Retrieved 16 October 2010.

- ↑ Gadsby, Meredith (2006), Sucking Salt: Caribbean Women Writers, Migration, and Survival, University of Missouri Press, pp. 76–77.

- ↑ R. Bhopal, "Glossary of terms relating to ethnicity and race: for reflection and debate", Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 2004; 58:441–445. Retrieved 6 October 2006.

- ↑ "Southall Black Sisters Home » Southall Black Sisters". Southall Black Sisters.

- ↑ Bhopal, Raj (2004). "Glossary of terms relating to ethnicity and race: for reflection and debate". Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 58 (6): 441–445. doi:10.1136/jech.2003.013466.

- ↑ "Language and the BSA: Ethnicity & Race". British Sociological Association. March 2005. Archived from the original on 27 April 2015. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ↑ Verma, Jatinder (2008-01-10). "What the migrant saw", The Guardian, 10 January 2008. Jatinder Verma, founder in 1977 of Tara Arts, the first Asian theatre company in Britain: "Everywhere my friends and I looked, it seemed black people, as we identified ourselves, were victims of white oppression." Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/g2/story/0,,2238188,00.html.

- ↑ What is meant by Black and Asian? "In the 1970s Black was used as a political term to encompass many groups who shared a common experience of oppression – this could include Asian but also Irish, for example."

- ↑ "The term Black and Asian – a Short History" "In the late 1960s through to the mid-1980s, we progressives called ourselves Black. This was not only because the word was reclaimed as a positive, but we also knew that we shared a common experience of racism because of our skin colour."

- ↑ "New Black Arts Alliance – Welcome". Blackartists.org.uk. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ↑ The Black Arts Alliance encourages "a coming together of Black people from Africa, Asia and the Caribbean because our histories have parallels of oppression"

- ↑ Their website intro states "Black Arts Alliance is 21 years old. Formed in 1985 it is the longest surviving network of Black artists representing the arts and culture drawn from ancestral heritages of South Asia, Africa, South America, and the Caribbean and, in more recent times, due to global conflict, our newly arrived compatriots known collectively as refugees." the Black Arts Alliance.

- ↑ National Black Police Association states that their "emphasis is on the common experience and determination of the people of African, African-Caribbean, and Asian origin to oppose the effects of racism."

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Ethnic group". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- ↑ "Multiculturalism the Wembley Way", BBC News, 8 September 2005. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- 1 2 "Scotland's New Official Ethnicity Classification" (PDF). General Register Office for Scotland. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- ↑ The Map Room: Africa: Sierra Leone, British Empire. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ↑ Exhibitions & Learning online | Black presence | Work and community, The National Archives. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ↑ Ferguson, William Stenner. Why I Hate Canadians, 1997.

- ↑ Ann Wuyts, "Evidence of 'upper class' Africans living in Roman York", The Independent, 2 March 2010. Retrieved 26 April 2015

- ↑ "Africans in Roman York?" University of Reading, 26 February 2010. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ↑ "Centuries old Beachy Head Lady's face revealed". BBC News. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- ↑ "Yorkshire clan linked to Africa". BBC. 24 January 2007. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ↑ Gover, Dominic (18 September 2013). "The First Black Briton? 1,000 Year Old Skeleton of African Woman Discovered by Schoolboys in Gloucestershire River". International Business Times. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- 1 2 Archer, Megan (20 September 2013). "Fairford schoolboys who found skull are fascinated to hear it dates back 1,000 years". Wilts and Gloucestershire Standard. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ↑ "1,000 Year Old Skeleton of African Woman Discovered by Schoolboys in Gloucestershire River".

- ↑ "Morien". ancienttexts.org. Celtic Literature Collective. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- ↑ "John Blanke-A Trumpeter in the court of King Henry VIII" Archived 26 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine.. Blackpresence, 12 March 2009. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ↑ Anne. "John Blanke and the More Taubronar: Renaissance African Musicians at Peckham Library". Miranda Kaufmann. Retrieved 22 March 2014.

- ↑ Richard Hakluyt. The Principal Navigations, Voyages, Traffiques, and Discoveries of the English Nation, The second voyage to Guinea set out by Sir George Barne, Sir John Yorke, Thomas Lok, Anthonie Hickman and Edward Castelin, in the yere 1554. The Captaine whereof was M. John Lok. E. P. Dutton & Co. p. 522. Retrieved 22 March 2014 – via Perseus.tufts.edu.

- ↑ Wood, Michael (2003-01-01). In Search of Shakespeare. BBC. ISBN 9780563534778.

- 1 2 3 4 Charles Nicholl. "The Lodger: Shakespeare on Silver Street".

- ↑ Ira Berlin, Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America, Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 1998 Pbk, p.39

- ↑ Ian Mortimer, p, 119. "The Time Traveller's Guide to Elizabethan England".

- ↑ Liza Picard. "Elizabeth's London: Everyday Life in Elizabethan London".

- ↑ "Guildhall Library Manuscripts Section".

- ↑ Ian Mortimer, p 120. "The Time Traveller's Guide to Elizabethan England".

- ↑ "Britain's first black community in Elizabethan London". BBC.

- ↑ "John Blanke takes his rightful place in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography!". September 25, 2014.

- ↑ "Black Tudors by Miranda Kaufmann — a hidden history".

- ↑ Ian Mortimer. "The Time Traveller's Guide to Elizabethan England".

- ↑ p119. "The Time Traveller's Guide to Elizabethan England".

- ↑ "The Lodger: Shakespeare on Silver Street".

- ↑ Ian Mortimer. "The Time Traveller's Guide to Elizabethan England".

- ↑ Taunya Lovell Banks, "Dangerous Woman: Elizabeth Key's Freedom Suit – Subjecthood and Racialized Identity in Seventeenth Century Colonial Virginia", 41 Akron Law Review 799 (2008), Digital Commons Law, University of Maryland Law School, accessed 21 Apr 2009

- ↑ "Exhibitions & Learning online | Black presence | Early times". The National Archives. Retrieved 18 October 2016.

- ↑ "CaspanVanSenden". Miranda Kaufmann. 28 February 2005. Retrieved 22 March 2014.

- ↑ "National Archives: Elizabeth I". nationalarchives.gov.uk.

- ↑ "HabibTLS". mirandakaufmann.com.

- ↑ "New Book". narrative-eye.org.uk. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013.

- ↑ "Thesis". mirandakaufmann.com.

- ↑ Banton, Michael (1955), The Coloured Quarter, London: Jonathan Cape.

- ↑ Shyllon, Folarin. "The Black Presence and Experience in Britain: An Analytical Overview", in Gundara and Duffield, eds (1992), Essays on the History of Blacks in Britain, Avebury, Aldershot.

- 1 2 3 4 Costello, Ray (2001). Black Liverpool: The Early History of Britain's Oldest Black Community 1730–1918. Liverpool: Picton Press. ISBN 1-873245-07-6. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ↑ McIntyre-Brown, Arabella; Woodland, Guy (2001). Liverpool: The First 1,000 Years. Liverpool: Garlic Press. p. 57. ISBN 1-904099-00-9.

- ↑ Mariners, Merchants and the Military too - A History of the British Empire.

- ↑ "What evidence is there of a black presence in Britain and north west England?". Revealing Histories.

- ↑ "Black Communities". The Proceedings of the Old Bailey.

- ↑ Shyllon, F. O. (1977-01-01). Black People in Britain 1555–1833. Institute of Race Relations. ISBN 9780192184139.

- ↑ page v, Ignatius Sancho. "Letters of the Late Ignatius Sancho, an African: To which are Prefixed".

- ↑ Julie Winch, p. "A Gentleman of Color: The Life of James Forten".

- ↑ "Ignatius Sancho (c1729-1780): The Composer". The Abolition Project.

- ↑ Winder, Robert (2010). Bloody Foreigners: The Story of Immigration to Britain. Hachette.

- ↑ "The Black Figure in 18th-century Art". BBC.

- ↑ "Revealing Histories: Remembering Slavery".

- 1 2 Winder. "Bloody Foreigners: The Story of Immigration to Britain".

- ↑ Black People in Britain 1555–1833. by Folarin Shyllon Review by: Arthur Sheps. p. 45.

- ↑ "Frederick Douglass Project: Terry's Allen's "Blacks in Britain" Essay". River Campus Libraries.

- ↑ "Black Lives in England". Historic England.

- ↑ "Silver Service Slavery: The Black Presence in the White Home". Victoria and Albert Museum (VAM).

- ↑ "Arriving in Britain". National Archives.

- 1 2 "The First Black Britons". BBC.

- ↑ "A Gentleman of Color: The Life of James Forten".

- ↑ Tukufu Zuberi, Antonio McDaniel, p 25 -26. "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot: The Mortality Cost of Colonizing Liberia in the ..."

- ↑ "Common Law". Miranda Kaufmann. Retrieved 22 March 2014.

- ↑ Sivapragasam, Michael, ‘Why Did Black Londoners not join the Sierra Leone Resettlement Scheme 1783–1815?’ Unpublished Masters dissertation (London: Open University, 2013), pp. 10–11.

- ↑ Great Britain. Court of King's Bench, Sylvester, p 301. "Reports of Cases Argued and Determined in the Court of King's ..., Volume 4".

- ↑ "Bloody Foreigners: The Story of Immigration to Britain".

- ↑ Robert Winder, Robert. "Bloody Foreigners: The Story of Immigration to Britain". pp. 103–104.

- ↑ Winder. Bloody Foreigners: The Story of Immigration to Britain.

- ↑ Edwards, Paul (September 1981). "The History of Black People in Britain". History Today.

- ↑ Sukhdev Sandhu. "The First Black Britons". BBC.

- ↑ Winder. Bloody Foreigners: The Story of Immigration to Britain.

- ↑ Sivapragasam, Michael, ‘Why Did Black Londoners not join the Sierra Leone Resettlement Scheme 1783–1815?’ Unpublished Masters dissertation (London: Open University, 2013), p. 3.

- 1 2 Bartels, Emily C. (2006). "Too Many Blackamoors: Deportation, Discrimination, and Elizabeth I" (PDF). Studies in English Literature. 46 (2): 305–322. doi:10.1353/sel.2006.0012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 June 2010.

- ↑ Gerzina, Gretchen (1995). Black London: Life before Emancipation. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press. p. 5. ISBN 0-8135-2259-5.

- ↑ Sivapragasam, Michael, ‘Why Did Black Londoners not join the Sierra Leone Resettlement Scheme 1783–1815?’ Unpublished Masters dissertation (London: Open University, 2013), pp. 3–4.

- ↑ Julie Winch, 60–61. "A Gentleman of Color: The Life of James Forten".

- ↑ Edmund Heward (1979). Lord Mansfield. p. 141.

- ↑ "The Black Poor". National Archive.

- 1 2 3 4 File, Nigel, and Chris Power (1981), Black Settlers in Britain 1555–1958, Heinemann Educational.

- ↑ "The First Black Britons".

- ↑ "African Americans in the American Revolution".

- ↑ Sivapragasam, Michael, ‘Why Did Black Londoners not join the Sierra Leone Resettlement Scheme 1783–1815?’ Unpublished Masters dissertation (London: Open University, 2013).

- ↑ Fryer, Peter (1984). Staying Power: The History of Black People in Britain. pp. 195 quotes a contemporary commentator who called them "indigent, unemployed, despised and forlorn", saying that "it was necessary they should be sent somewhere, and be no longer suffered to invest [sic] the streets of London" (C. B. Wadström, An Essay on Colonization, 1794–5, II, 220).

- ↑ Sumita Mukherjee, "‘Narrow-majority’ and ‘Bow-and-agree’: Public Attitudes Towards the Elections of the First Asian MPs in Britain, Dadabhai Naoroji and Mancherjee Merwanjee Bhownaggree, 1885–1906", Journal of the Oxford University History Society, 1 (2004), p. 3.

- ↑ "Black Victorians/Black Victoriana".

- 1 2 "BBC:Short History of Immigration". BBC WEBSITE.

- ↑ "Black Victorians/Black Victoriana".

- ↑ Panikos, Panayi (2014). An Immigration History of Britain. Routledge.

- ↑ Panikos. An Immigration History of Britain. p. 20.

- ↑ "Black Victorians/Black Victoriana".

- ↑ Sukhdev Sandhu. "The First Black Britons". BBC History.

- ↑ "memoirs read before the anthropological society of london p52".

- ↑ Geoffrey Bell, The Other Eastenders: Kamal Chunchie and West Ham's early black community, Stratford: Eastside Community Heritage, 2002.

- ↑ "Pablo Fanque, Black Circus Proprietor". 100 Great Black Britons. Retrieved 22 March 2014.

- ↑ A. H. Saxon, The Life and Art of Andrew Ducrow, Archon Books, 1978.