Gorani people

Goranci on Gora map | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 60,000 (estimate)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 10,265 (2011 census)[2] | |

| 7,767 (2011 census)[3] | |

| 10,000+ | |

| 2,000+ | |

| 428 (2011 census)[4] | |

| 418 (2001 census)[5] | |

| 197 (2011 census)[6] | |

| 24 (2013 census)[7] | |

| Languages | |

| Gora dialect, Macedonian, Bosnian, Serbian, Albanian | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Bosniaks, Bulgarians, Torbeši, Pomaks, Serbs[8][9][10][11] | |

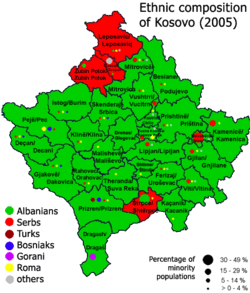

The Gorani [ɡɔ̌rani] or Goranci [ɡɔrǎːntsi]; (Cyrillic: Горани or Горанци) are a Slavic Muslim ethnic group inhabiting the Gora region - the triangle between Kosovo,[lower-alpha 1] Albania, and Macedonia. They number an estimated 60,000 people, and speak a transitional South Slavic dialect, called Goranski.

Ethnography

The ethnonym Goranci, meaning "highlanders", is derived from the Slavic toponym gora, which means "hill, mountain". Another autonym of this people is Našinci,[12] which literally means "our people, our ones".

In Kosovo they are often termed Bosniak-Kosovar, Bulgarians, Macedonians and Serbs but the general view is that they are a distinct minority group, which is their own view of themselves.[13][14] By the last censuses at the end of 20th century in Yugoslavia they have declared themselves to be Muslims by nationality.[15]

In the mid-1980s, the Macedonian press labeled them Torbeši (Macedonian Muslims).[15]

In Albania, they are known by the Albanians with several exonyms, pejoratives, such as Bulgareci ("Bulgarians"),[16] Torbeshë ("bag carriers"), Poturë ("turkified", from po-tur, literally not Turk but, "turkified", used for Islamized Slavs)[17] and Goranci.

The Goranci continue to practice Djurdjevdan, which is the Saint George's Day of the Orthodox South Slavs.[18] They have historically worked as pečalbari (migrant workers), exclusively in cities, throughout the Ottoman Empire in cities such as Istanbul and Thessaloniki, among others.[19]

In Gora, the Goranci have mostly resisted "Bosniakization". In other areas of the Šar Mountains, Slavic Muslims declare either as Muslims by ethnicity or as Bosniaks.

Population

.png)

In Kosovo, the Goranci number 10,265 inhabitants,[2] which is drastically lower than before the Kosovo War. In 1998, it was estimated that their total population number was at least 50,000.[20]

Most Goranci state that the unstable situation and economic issues drive them to leave Kosovo. There is also some mention of threats and discrimination by ethnic Albanians.[21] The UN administration in Kosovo, UNMIK, has redrawn internal boundaries in the province in such a way that a Goranci-majority municipality no longer exists. The Gora municipality was combined with the neighboring Albanian-inhabited region of Opolje (some 20,000 people) into a new subdivision named Dragaš, which now has an Albanian majority.

- Settlements

In Albania, there are 10 Gorani-inhabited villages: Zapod, Pakisht, Orçikël, Kosharisht, Cernalevë, Orgjost, Orshekë, Borje, Novosej and Shishtavec.[22][23]

In Kosovo, there are 21 Gorani-inhabited villages: Baćka, Brod, Vranište, Globočica, Gornja Rapča, Gornji Krstac, Dikance, Donja Rapča, Donje Ljubinje, Gornje Ljubinje, Donji Krstac, Dragaš, Zli Potok, Kruševo, Kukuljane, Lještane, Ljubošte, Mlike, Orčuša, Radeša and Restelica.[23]

In the Republic of Macedonia, there are 2 Goranci-inhabited villages: Jelovjane and Urvič.[24][25]

History

Contemporary

In 2007 the Kosovar provisional institutions opened a school in Gora to teach the Bosnian language, which sparked minor consternation amongst the Goranci population, added by the fact that the Principal declares as an Albanian. Many Goranci refuse to send their children to school due to societal prejudices, and threats of assimilation to Bosniaks or Albanians. Consequently, Goranci organized education per Serbia's curriculum.

Goranci activists in Serbia's proper stated they want Gora (a former municipality) to join the Association of Serb Municipalities, causing added pressure on the Gorani Community in Kosovo.[26]

In 2018 Bulgarian activists among Gorani have filed a petition in the country's parliament demanding their official recognition as a separate minority.[27]

Culture

Religion

In the 18th century, a wave of Islamization began in Gora.[28] The Ottoman abolition of the Bulgarian Archbishopric of Ohrid and Serbian Patriarchate of Peć in 1766/1767 is thought to have prompted the Islamization of Gora as was the trend of many Balkan communities.[29] The last Christian Gorani, Božana, died in the 19th century - she has received a cult, signifying the Goranci's Christian heritage, collected by Russian consuls Anastasiev and Yastrebov in the second half of the 19th century.[28]

Traditions

The Goranci are known for being "the best confectioners and bakers" in former Yugoslavia.[30]

The Slavs of Gora were Christianized in 870 following the Byzantine Empire's baptism of the Serbs and Bulgarians. The Ottomans conquered the region in the 14th century, which started the process of Islamization of the Gorani and neighbouring Albanians. However, the Gorani still tangentially observe some Orthodox Christian traditions, such as Slavas and Djurdjevden, and like Serbs they know their Onomastik or saint’s days. Although most Gorani are Sunni Muslims, Sufism and in particular the Halveti and Bektashi Sufi orders (both of which are Shia Muslims) are widespread.

Traditional Gorani folk music includes a two-beat dance called "oro" ('circle'), which is a circle dance focused on the foot movements: it always starts on the right foot and moves in an anti-clockwise direction. The Oro is usually accompanied by instruments such as curlje, kaval, čiftelija or tapan, and singing is used less frequently in the dances than in those of the Albanians and Serbs.

The "national" sport of Pelivona is a form of Oil wrestling is popular among Gorani with regular tournaments being held in the outdoors to the accompaniment of Curlje and Tapan with associated ritualized hand gestures and dances, with origins in the Middle East through the Ottoman Empire's conquest of Balkans.

The "national" drink of the Gorani is Rakija which is commonly distilled at home by elderly people. Another popular drink is Turkish Coffee which is drunk in small cups accompanied by a glass of water. Tasseography is popular among all Gorani using the residue of Turkish Coffee.

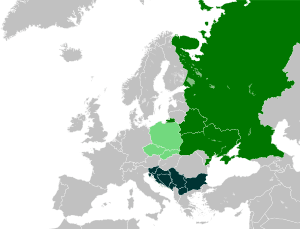

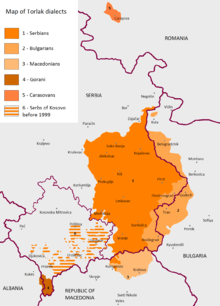

Language

The Gorani people speak South Slavic, a local dialect known as "Našinski"[22] or "Goranski", which is part of a wider Torlakian dialect, spoken in Western Bulgaria, Southern Serbia and part of Macedonia. The Slavic dialect of the Gorani community is known as Gorançe by Albanians.[22] Within the Gorani community there is a recognition of their dialects being closer to the Macedonian language, than to Serbian.[31] The Torlakian dialect is a transitional dialect of Bulgarian and Serbian whilst also sharing features with Macedonian. The Gorani speech is classified as an Old-Shtokavian dialect of Serbian (Old Serbian), the Prizren-Timok dialect. Bulgarian linguists classify the Gorani dialect as part of a Bulgarian dialectal area.[32] Within scholarship the Goran dialects previously classified as belonging to Serbian have been reassigned as belonging to Macedonian in the 21 century.[31] Gorani speech has numerous loan words, being greatly influenced by Turkish and Arabic due to the influence of Islam, as well as Albanian areally. It is similar to the Bosnian language because of the numerous Turkish loanwords. Gorani speak Serbo-Croatian in school.[15]

According to the last 1991 Yugoslav census, 54.8% of the inhabitants of the Gora municipality said that they spoke the Gorani language, while the remainder had called it Serbian.[33] Some Gorani scholars define their language as Bulgarian, similar to the Bulgarian dialects spoken in the north western region of the Republic of Macedonia.[34] Some linguists, including Vidoeski, Brozovic and Ivic, identify the Slavic-dialect of the Gora region as Macedonian.[35] There are assertions that Macedonian is spoken in 50 to 75 villages in the Gora region (Albania and Kosovo).[36] According to some unverified sources in 2003 the Kosovo government acquired Macedonian language and grammar books for Gorani school.[37]

Albanian-Gorani scholar Nazif Dokle compiled the first Gorani–Albanian dictionary (with 43,000 words and phrases) in 2007, sponsored and printed by the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences.[34] In 2008 the first issue of a Macedonian language newspaper, Гороцвет (Gorocvet) was published.[38]

- Verno libe

- Gledaj me gledaj libe, abe verno libe,

- nagledaj mi se dur ti som ovde.

- Utre ke odim abe verno libe dalek-dalek

- na pusti Gurbet.

- Racaj poracaj libe šo da ti kupim.

- Ti da mi kupiš

- abe gledaniku cerna šamija, ja da ga nosim

- abe gledaniku i da ga želam.

- Racaj poracaj abe verno

- libe šo da ti pratim

- Ti da mi pratiš abe

- gledaniku šarena knjiga

- Ja da ga pujem abe

gledaniku i da ga želam

Politics

People

- Fahrudin Jusufi, former Yugoslav footballer, born in Zli Potok[39]

- Miralem Sulejmani, Serbian footballer, of Gorani descent[40]

- Almen Abdi, Swiss footballer, of Gorani descent

- Zufer Avdija, Serbian-Israeli basketball player

See also

Notes

- ↑ Kosovo is the subject of a territorial dispute between the Republic of Kosovo and the Republic of Serbia. The Republic of Kosovo unilaterally declared independence on 17 February 2008, but Serbia continues to claim it as part of its own sovereign territory. The two governments began to normalise relations in 2013, as part of the Brussels Agreement. Kosovo has received formal recognition as an independent state from 113 out of 193 United Nations member states.

References

- ↑ "Progam političke stranke GIG".

Do Nato intervencije na Srbiju, 24.03.1999.godine, u Gori je živelo oko 18.000 Goranaca. U Srbiji i bivšim jugoslovenskim republikama nalazi se oko 40.000 Goranaca, a značajan broj Goranaca živi i radi u zemljama Evropske unije i u drugim zemljama. Po našim procenama ukupan broj Goranaca, u Gori i u rasejanju iznosi oko 60.000.

- 1 2 "Population by gender, ethnicity and settlement level" (PDF). p. 12. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 April 2014. Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- ↑ "Population by ethnicity". Serbian Statistical Office (in Serbian). Serbian Statistical Office. Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- ↑ "1. Population by ethnicity - detailed classification, 2011 census". Statistics of Croatia. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

- ↑ "2.39 Factors of the nationality of the population based on affiliation with cultural values, knowledge of languages". Statistics of Hungary. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- ↑ "Table CG5. Population by ethnicity and religion". Montenegrin Office of Statistics. Montenegrin Office of Statistics. Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- ↑ "1. Stanovništvo prema etničkoj/nacionalnoj pripadnosti - detaljna klasifikacija". Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ↑ "The Palgrave Handbook of Slavic Languages, Identities and Borders". Google Books. Palgrave. Retrieved 15 April 2016.

- ↑ "Goranis want to join community of Serb municipalities". B92. B92. Retrieved 15 April 2016.

- ↑ "Gorani decide against forming minority council". B92. B92. Retrieved 15 April 2016.

- ↑ "Slow exodus threatens Kosovo's mountain Gorani". Reuters. Reuters. Retrieved 15 April 2016.

- ↑ Xhelal Ylli, Erlangen: "Sprache und Identität bei den Gorani in Albanien: 'Nie sme nasinci'."

- ↑ "Kosovo". google.com.

- ↑ "Historical Dictionary of Kosova". google.com.

- 1 2 3 Duijzings 2000, p. 27.

- ↑ Miranda Vickers; James Pettifer (1997). Albania: From Anarchy to a Balkan Identity. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. pp. 205–. ISBN 978-1-85065-279-3.

- ↑ Dokle, Nazif. Reçnik Goransko (Nashinski) -albanski, Sofia 2007, Peçatnica Naukini akademiji "Prof. Marin Drinov", s. 5, 11

- ↑ Mirko Čupić (2006). Oteta zemlja: Kosovo i Metohija (zločini, progoni, otpori...). Nolit. p. 22.

Сви Горанци знају да су православног порекла, али им није јасно због чега се нису вратили у своју веру, после ослобођења 1912. године. Вероватно је ондашња Краљевина веровала да ће се боље сачувати граница ако ...

- ↑ Zorica Divac (2002). Običaji životnog ciklusa u gradskoj sredini: Beograd, 6-8. septembar 2001. Etnografski institut SANU. p. 261. ISBN 978-86-7587-024-1.

- ↑ Eastern Europe: Newsletter. 12–13. Eastern Europe. 1998. p. 22.

- ↑ Update on the Kosovo Roma, Ashkaelia, Egyptian, Serb, Bosniak, Gorani and Albanian communities in a minority situation, UNHCR Kosovo, June 2004

- 1 2 3 Steinke, Klaus; Ylli, Xhelal (2010). Die slavischen Minderheiten in Albanien (SMA). 3. Gora. Munich: Verlag Otto Sagner. p. 11. ISBN 978-3-86688-112-9. "In den 17 Dörfern des Kosovo wird Našinski/Goranče gesprochen, und sie gehören zu einer Gemeinde mit dem Verwaltungszentrum in Dragaš. Die 19 Dörfer in Albanien sind hingegen auf drei Gemeinden des Bezirks Kukës aufgeteilt, und zwar auf Shishtavec, Zapod und Topojan. Slavophone findet man freilich nur in den ersten beiden Gemeinden. Zur Gemeinde Shishtavec gehören sieben Dörfer und in den folgenden vier wird Našinski/Goranče gesprochen: Shishtavec (Šištaec/Šišteec), Borja (Borje), Cërnaleva (Cărnolevo/Cărneleve) und Oreshka (Orešek). Zur Gemeinde Zapod gehören ebenfalls sieben Dörfer, und in den folgenden fünf wird Našinski/Goranče gesprochen: Orgjost (Orgosta), Kosharisht (Košarišta), Pakisht (Pakiša/Pakišča) Zapod (Zapod) und Orçikla (Orčikl’e/Očikl’e)’. In der Gemeinde Topojan gibt es inzwischen keine slavophone Bevölkerung mehr. Die Einwohner selbst bezeichnen sich gewöhnlich als Goranen ‘Einwohner von Gora oder Našinci Unsrige, und ihre Sprache wird von ihnen als Našinski und von den Albanern als Gorançe bezeichnet."

- 1 2 Vlašković, Zoran (2013-02-07). "Goranci u obruču brane Srbiju" (in Serbian). Press Online. Retrieved 5 May 2015.

- ↑ Гласник Српског географског друштва (1947). Volumes 27-30. Srpsko geografsko društvo. p. 107. "Данашњи становници Урвича и Јеловјана на супротној, полошкој страни Шар-Планине, пореклом су Горани. Много су више утицале на исељавање Горана политичке промене, настале после 1912 године. Тада се скоро четвртина становништва иселила у Турску, за коју су се преко вере и дуге управе били интимно везали. Још једна миграција јаче је захватила Горане, али не у нашој земљи, него оне који су остали у границама Арбаније."

- ↑ Vidoeski, Božidar (1998). Dijalektite na makedonskiot jazik. Vol. 1. Makedonska akademija na naukite i umetnostite. pp. 309, 315. ISBN 9789989649509.

Во западна Македонија исламизирано македонско население живее во неколку географски региони на македонско-албанската пограничје:... во Полог (Јеловјане, Урвич)." "Автентичниот горански говор добро го чуваат и жителите во муслиманските оази Урвич и Јеловјане во Тетовско иако тие подолго време живеат во друго дијалектно окружување.

- ↑ "Goranci: Ne želimo u Dragaš već u Zajednicu srpskih opština" (in Serbian). Blic. 2013-11-08.

- ↑ Bulgarian National Radio, Ethnic Bulgarians in Kosovo demand recognition of their community. Published on 5/30/18.

- 1 2 Бурсаћ 2000, pp. 71-73 (Орхан Драгаш)

- ↑ Religion and the Politics of Identity in Kosovo

- ↑ Siniša Ljepojević; Milica Radovanović (2006). Kosovo and Metohija: reality, economy and prejudices. TANJUG. p. 124.

- 1 2 Friedman, Victor (2006). "Albania/Albanien". In Ammon, Ulrich. Sociolinguistics: An International Handbook of the Science of Language and Society, Volume 3. Walter de Gruyte. p. 1879. ISBN 9783110184181. "The Gorans, who are also Muslim, have a separate identity. The Goran dialects used to be classed with Serbian, but have more recently been assigned to Macedonian, and Gorans themselves recognize that their dialects are closer to Macedonian than to Serbian."

- ↑ Младенов, Стефан. Пътешествие из Македония и Поморавия, в: Научна експедиция в Македония и Поморавието 1916, София 1993, с. 184. (Mladenov, Stefan. Journey through Macedonia and Pomoraviya, in: Scientific expeditions in Macedonia and Pomoraviya 1916, Sofia 1993, p. 184) Асенова, Петя. Архаизми и балканизми в един изолиран български говор (Кукъска Гора, Албания), Балканистични четения, посветени на десетата годишнина на специалност "Балканистика" в СУ "Св. Климент Охридски", ФСлФ, София, 17-19 май 2004 (Assenova, Petya. Archaisms and Balkanisms in an isolated Bulgarian dialect (Kukas Gora, Albania), Balkan studies readings on the tenth anniversary of the major Balkan studies in Sofia University, 17–19 May 2004)

- ↑ "Gorani speech by dr. Radivoje Mladenovic" (PDF). rastko.org.rs (in Serbian). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 February 2014.

- 1 2 Dokle, Nazif. Reçnik Goransko (Nashinski) - Albanski, Sofia 2007, Peçatnica Naukini akademiji "Prof. Marin Drinov", s. 5, 11, 19 (Nazif Dokle. Goranian (Nashinski) - Albanian Dictionary, Sofia 2007, Published by Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, p. 5, 11, 19)

- ↑ "Macedonian by Victor Friedman, pg 4 (footnote)". seelrc.org.

- ↑ "Macedonian by Victor Friedman, pg 6". seelrc.org.

- ↑ Focus News (4 July 2003) Kosovo Government Acquires Macedonian language and grammar books for Gorani Minority Schools

- ↑ "Матица на иселениците од Македонија". Матица на иселениците од Македонија.

- ↑ "Goranac sam. Ako to uopšte nekog i interesuje" (in Serbo-Croatian) (issue 1338). Tempo (Serbia magazine). 16 October 1991. p. 14.

- ↑ "Ličnost Danas: Miralem Sulejmani". 2009.

Sources

- Books

- Ahmetović, B. (1999). Gora i Goranci. Beograd: Inter Ju pres.

- Duijzings, Ger (2000). Religion and the Politics of Identity in Kosovo. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. ISBN 978-1-85065-431-5.

- Lutovac, Milisav V. (1955). Gora i Opolje: antropogeografska proučavanja. Naučna knjiga.

- Gora, Opolje i Sredska. Geografski institut "Jovan Cvijić" SANU. 1997. ISBN 978-86-80029-04-7.

- Journals

- Đorđević-Crnobrnja, Jadranka (2014). "Migrations from the Gora region at the end of the 20th and the beginning of the 21st century". Glasnik Etnografskog instituta SANU. 62 (2). doi:10.2298/GEI1402035D.

- Friedman, Victor (2006). "Determination and Doubling in Balkan Borderlands" (PDF). Harvard Ukrainian Studies. 1–4: 105–116.

- Milenović, Živorad (2010). "The formation of Goran's ethnic community in Kosovo and Metohia from 1918 until now" (PDF). Baština. 28: 223–230.

- Tomašević, Radovan (1989). "ŠARPLANINSKI NAŠINCI" (PDF). Etnološke sveske. 10: 47–57.

- Symposia

- Bursać, Milan, ed. (2000), ГОРАНЦИ, МУСЛИМАНИ И ТУРЦИ У ШАРПЛАНИНСКИМ ЖУПАМА СРБИЈЕ: ПРОБЛЕМИ САДАШЊИХ УСЛОВА ЖИВОТА И ОПСТАНКА: Зборник радова са “Округлог стола” одржаног 19. априла 2000. године у Српској академији наука и уметности, Belgrade: SANU

- Antonijević, Dragoslav (2000), Етнички идентитет Горанаца (PDF), pp. 23–29

- Dragaš, Orhan (2000), О Горанцима (PDF), pp. 71–73

- Antonijević, Dragoslav (1995), "Identitet Goranaca", Međunarodna konferencija Položaj manjina u Saveznoj Republici Jugoslaviji, zbornik radova, Belgrade: SANU

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gorani people. |

- "Project Rastko - Gora: E-library of culture and tradition of Gora and Goranies". Project Rastko. Archived from the original on 9 September 2012.

- "The minorities within the minority". The Economist. 2006-11-02.

- Zejnel Zejneli (9 November 2010). "Gora i Goranci – čiji su" (in Serbian). Srpska dijaspora. Archived from the original on 30 November 2010.

- "Svi hoće da "prekrste" Gorance" (in Serbian). Vesti Online. 2011-05-07.

- Biljana Jovičić (2009-09-05). "Gora čuva Gorance od zaborava" (in Serbian). RTS.