Indo-European migrations

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

|

|

Origins |

|

Archaeology Pontic Steppe Caucasus East Asia Eastern Europe Northern Europe Pontic Steppe Northern/Eastern Steppe Europe

South Asia Steppe Europe Caucasus India |

|

Peoples and societies Indo-Aryans Iranians Europe East Asia Europe Indo-Aryan Iranian |

|

|

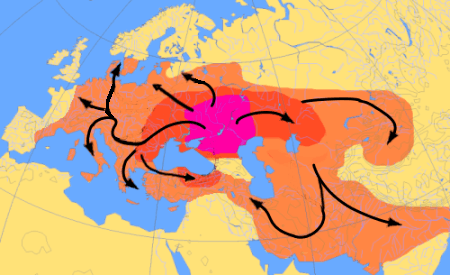

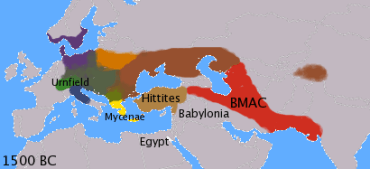

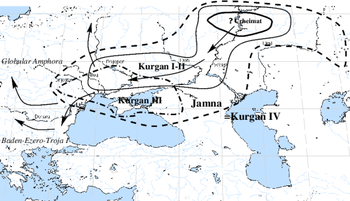

Indo-European migrations were the migrations of pastoral peoples speaking the Proto-Indo-European language (PIE), who departed from the Yamnaya and related cultures in the Pontic–Caspian steppe, starting at c. 4000 BCE. Their descendants spread throughout Europe and parts of Asia, forming new cultures with the people they met on their way, including the Corded Ware culture in Northern Europe and the Vedic culture in the Indian subcontinent. These migrations ultimately seeded the cultures and languages of most of Europe, Greater Iran, and much of the Indian subcontinent (and subsequently resulted in the largest and most broadly spoken language family in the world).

Modern knowledge of these migrations is based on data from linguistics, archaeology, anthropology and genetics. Linguistics describes the similarities between various languages, and the linguistic laws at play in the changes in those languages (see Indo-European studies). Archaeological data describes the spread of the Proto-Indo-European culture and language in several stages: from the Proto-Indo-European homeland (probably situated in the Pontic–Caspian steppe), into Western Europe, Central, South and (very sporadically) Eastern Asia by migrations and by language shift through elite-recruitment as described by anthropological research.[2][3] Recent genetic research has a growing contribution to the understanding of the historical relations between various historical cultures.

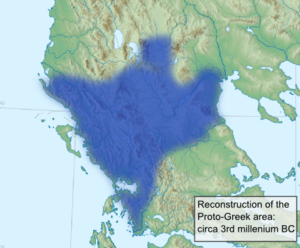

The Indo-European languages and cultures spread in various stages. Early migrations from c. 4200–3000 BCE brought archaic proto-Indo-European into the lower Danube valley,[4] Anatolia,[5][6][web 1] and the Altai region.[7]

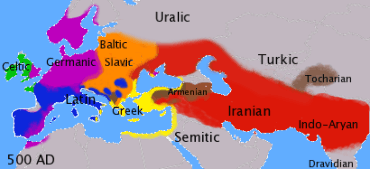

Proto-Celtic and Proto-Italic probably developed in and spread from Central Europe into western Europe after new Yamnaya migrations into the Danube Valley,[8][9] while Proto-Germanic and Proto-Balto-Slavic may have developed east of the Carpathian mountains, at present-day Ukraine,[10] moving north and spreading with the Corded Ware culture in Middle Europe (third millennium BCE).[11][12][web 2][13][web 3][web 4] Alternatively, a European branch of Indo-European dialects, termed "North-west Indo-European" and associated with the Beaker culture, may have been ancestral to not only Celtic and Italic, but also to Germanic and Balto-Slavic.[14]

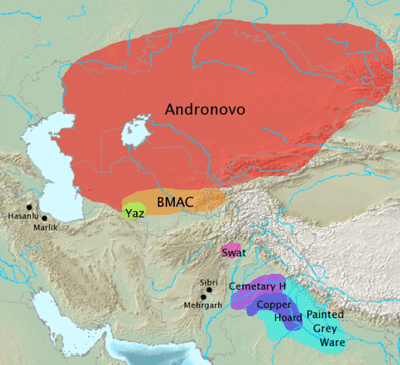

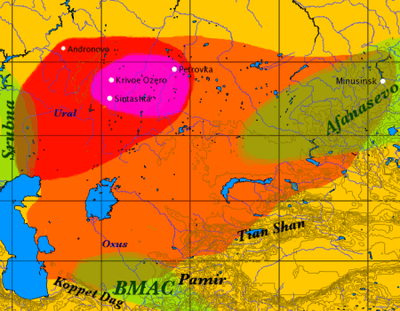

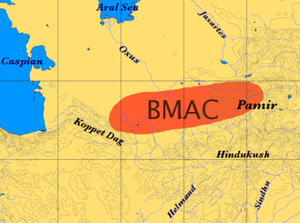

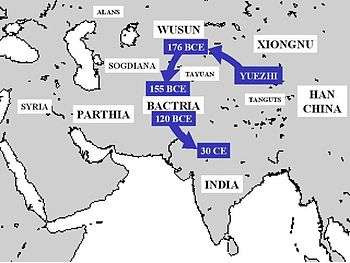

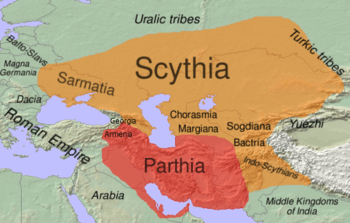

The Indo-Iranian language and culture emerged at the Sintashta culture (c. 2100–1800 BCE), at the eastern border of the Yamna horizon and the Corded ware culture, growing into the Andronovo culture (c. 1800–800 BCE). Indo-Aryans moved into the Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex (c. 2300–1700 BCE) and spread to the Levant (Mitanni), northern India (Vedic people, c. 1500 BCE), and China (Wusun).[3] The Iranian languages spread throughout the steppes with the Scyths and into Iran with the Medes, Parthians and Persians from ca. 800 BCE.[3]

Fundaments

Linguistics: relations between languages

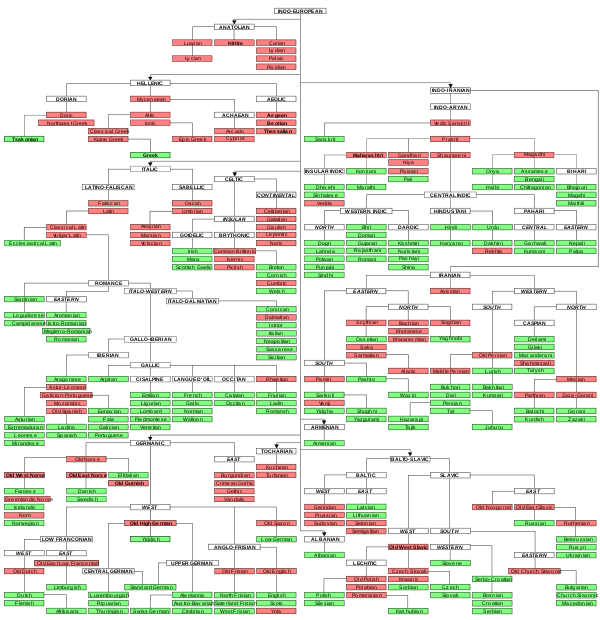

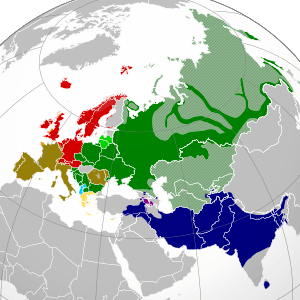

Indo-European languages

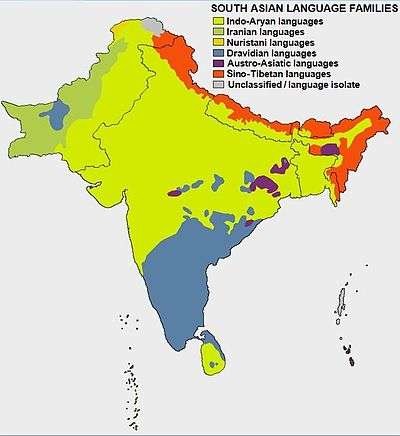

The Indo-European languages constitute a family of several hundred related languages and dialects. There are about 439 languages and dialects, according to the 2009 Ethnologue estimate, about half of these (221) belonging to the Indo-Aryan subbranch originating in South Asia.[web 5] The Indo-European family includes most of the major current languages of Europe, the Iranian plateau, the northern half of the Indian Subcontinent, Sri Lanka and was also predominant in ancient Anatolia. With written attestations appearing since the Bronze Age in the form of the Anatolian languages and Mycenaean Greek, the Indo-European family is significant to the field of historical linguistics as possessing the second-longest recorded history, after the Afroasiatic family.

Indo-European languages are spoken by almost 3 billion native speakers,[web 6] the largest number by far for any recognised language family. Of the 20 languages with the largest numbers of native speakers according to Ethnologue, twelve are Indo-European: Spanish, English, Hindi, Portuguese, Bengali, Russian, German, Punjabi, Marathi, French, Urdu, Italian, accounting for over 1.7 billion native speakers.[web 7]

The similarities between various European languages, Sanskrit and Persian were noted by Sir William Jones when learning Sanskrit in India, concluding that all these languages originated from the same source.[15][web 8] Several disputed proposals link Indo-European to other major language families.

Development of the Indo-European languages

Proto-Indo-European language

The Proto-Indo-European language (PIE) is the linguistic reconstruction of a common ancestor of the Indo-European languages spoken by the Proto-Indo-Europeans. PIE was the first proposed proto-language to be widely accepted by linguists. Far more work has gone into reconstructing it than any other proto-language and it is by far the most well-understood of all proto-languages of its age. During the 19th century, the vast majority of linguistic work was devoted to reconstruction of Proto-Indo-European or its daughter proto-languages such as Proto-Germanic, and most of the current techniques of historical linguistics (e. g. the comparative method and the method of internal reconstruction) were developed as a result.

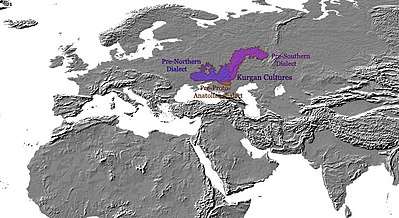

Scholars estimate that PIE may have been spoken as a single language (before divergence began) around 3500 BCE, though estimates by different authorities can vary by more than a millennium. The most popular hypothesis for the origin and spread of the language is the Kurgan hypothesis, which postulates an origin in the Pontic–Caspian steppe of Eastern Europe.

The existence of PIE was first postulated in the 18th century by Sir William Jones, who observed the similarities between Sanskrit, Ancient Greek, and Latin. By the early 20th century, well-defined descriptions of PIE had been developed that are still accepted today (with some refinements). The largest developments of the 20th century have been the discovery of Anatolian and Tocharian languages and the acceptance of the laryngeal theory. The Anatolian languages have also spurred a major re-evaluation of theories concerning the development of various shared Indo-European language features and the extent to which these features were present in PIE itself.

PIE is thought to have had a complex system of morphology that included inflections (suffixing of roots, as in who, whom, whose), and ablaut (vowel alterations, as in sing, sang, sung). Nouns used a sophisticated system of declension and verbs used a similarly sophisticated system of conjugation.

Relationships to other language families, including the Uralic languages, have been proposed but remain controversial. There is no written evidence of Proto-Indo-European, so all knowledge of the language is derived by reconstruction from later languages using linguistic techniques such as the comparative method and the method of internal reconstruction.

Pre-Proto-Indo-European

The Indo-Hittite hypothesis postulates a common predecessor for both the Anatolian languages and the other Indo-European languages, called Indi-Hittite or Indo-Anatolian.[2] Although it is obvious that PIE had predecessors,[16] the Indo-Hittite hypothesis is not widely accepted, and there is little to suggest that it is possible to reconstruct a proto-Indo-Hittite stage that differs substantially from what is already reconstructed for PIE.

A shared common ancestor of Indo-European and Uralic, Indo-Uralic, has been postulated as a possible pre-PIE.[17] According to Kortlandt, "Indo-European is a branch of Indo-Uralic which was radically transformed under the influence of a North Caucasian substratum when its speakers moved from the area north of the Caspian Sea to the area north of the Black Sea."[17][note 1] Anthony notes that the validity of such deep relationships cannot be reliably demonstrated due to the time-depth involved, and also notes that the similarities may be explained by borrowings from PIE into proto-Uralic.[16] Yet, Anthony also notes that the North Caucasian communities "were southern participants in the steppe world".[2]

| Spread of IE-languages II |

|---|

3500 BCE  2500 BCE  1500 BCE  500 BCE  500 CE |

| Spread of IE-languages I |

|---|

4000 BCE  3000 BCE  2000 BCE  500 BCE |

Genesis of Indo-European languages

Using a mathematical analysis borrowed from evolutionary biology, Don Ringe and Tandy Warnow propose the following evolutionary tree of Indo-European branches:[23]

- Pre-Anatolian (before 3500 BCE)

- Pre-Tocharian

- Pre-Celtic and Pre-Italic (before 2500 BCE)

- [Pre-Germanic?][note 2]

- Pre-Armenian and Pre-Greek (after 2500 BCE)

- [Pre-Germanic?][note 2]

- Pre-Balto-Slavic[23]

- Proto-Indo-Iranian (2000 BCE)

David Anthony, following the methodology of Ringe and Warnow, proposes the following sequence:[26]

- Pre-Anatolian (4200 BCE)

- Pre-Tocharian (3700 BCE)

- Pre-Germanic (3300 BCE)

- Pre-Celtic and Pre-Italic (3000 BCE)

- Pre-Armenian (2800 BCE)

- Pre-Balto-Slavic (2800 BCE)

- Pre-Greek (2500 BCE)

- Proto-Indo-Iranian (2200 BCE); split between Iranian and Old Indic 1800 BCE

Ringe and Warnow's methodology may be outdated, and not accurately reflect the development of the IE languages.

Archaeology: migrations from the steppe Urheimat

Archaeological research has unearthed a broad range of historical cultures which can be related to the spread of the Indo-European languages. Various steppe-cultures show strong similarities with the Yamna-horizon at the Pontic steppe, while the time-range of several Asian cultures also coincides with the proposed trajectory and time-range of the Indo-European migrations.[27][2]

According to the widely accepted Kurgan hypothesis or Steppe theory, the Indo-European language and culture spread in several stages from the Proto-Indo-European Urheimat in the Eurasian Pontic steppes into Western Europe, Central and South Asia, through folk migrations and so-called elite recruitment.[2][3] This process started with the introduction of cattle at the Eurasian steppes around 5200 BCE, and the mobilisation of the steppe herder cultures with the introduction of wheeled wagons and horse-back riding, which led to a new kind of culture. Between 4,500 and 2,500 BCE, this "horizon", which includes several distinctive cultures, spread out over the Pontic steppes, and outside into Europe and Asia.[2]

Early migrations at ca. 4200 BCE brought steppe herders into the lower Danube valley, either causing or taking advantage of the collapse of Old Europe.[4] According to Anthony, the Anatolian branch,[28] to which the Hittites belong,[29] probably arrived in Anatolia from the Danube valley.[5][30][web 1] According to Mathieson & Reich et al. (2017), it is unlikely that the Anatolian branch arrived in Anatolia via the Balkans.[31]

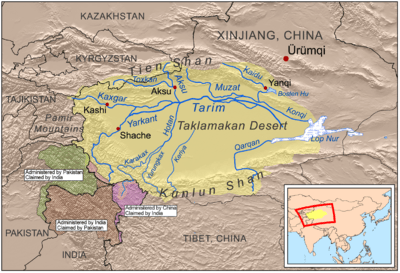

Migrations eastward from the Yamna culture founded the Afanasevo culture[7] which developed into the Tocharians.[32] The Tarim mummies may represent a migration of Tocharian speakers from the Afanasevo culture into the Tarim Basin.[33] Migrations southward may have founded the Maykop culture,[34] but the Maykop origins could also have been in the Caucasus.[35][web 10]

The western Indo-European languages (Germanic, Celtic, Italic) probably spread into Europe from the Balkan-Danubian complex, a set of cultures in Southeastern Europe.[8] At ca. 3000 BCE a migration of Proto-Indo-European speakers from the Yamna-culture took place toward the west, along the Danube river,[9] Slavic and Baltic developed a little later at the middle Dniepr (present-day Ukraine),[10] moving north toward the Baltic coast.[36] The Corded Ware culture in Middle Europe (third millennium BCE),[web 2] which materialized with a massive migration from the Eurasian steppes to Central Europe,[13][web 3][web 4] probably played a central role in the spread of the pre-Germanic and pre-Balto-Slavic dialects.[11][12]

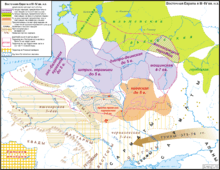

The eastern part of the Yamna horizon and the Corded ware culture contributed to the Sintashta culture (c. 2100–1800 BCE), where the Indo-Iranian language and culture emerged, and where the chariot was invented.[2] The Indo-Iranian language and culture was further developed in the Andronovo culture (c. 1800–800 BCE), and influenced by the Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex (c. 2300–1700 BCE). The Indo-Aryans split off around 1800–1600 BCE from the Iranians,[37] whereafter Indo-Aryan groups moved to the Levant (Mitanni), northern India (Vedic people, c. 1500 BCE), and China (Wusun).[3] The Iranian languages spread throughout the steppes with the Scyths and into Iran with the Medes, Parthians and Persians from ca. 800 BCE.[3]

Anthropology: Elite recruitment and language shift

According to Marija Gimbutas, the process of "Indo-Europeanization" of Europe was essentially a cultural, not a physical transformation.[38] It is understood as a migration of Yamnaya people to Europe, as military victors, successfully imposing a new administrative system, language and religion upon the indigenous groups, referred to by Gimbutas as Old Europeans.[39][note 3] The Yamnaya people's social organization, especially a patrilinear and patriarchal structure, greatly facilitated their effectiveness in war.[40] According to Gimbutas, the social structure of Old Europe "contrasted with the Indo-European Kurgans who were mobile and non-egalitarian" with a hierarchically organised tripartite social structure; the IE were warlike, lived in smaller villages at times, and had an ideology that centered on the virile male, reflected also in their pantheon. In contrast, the indigenous groups of Old Europe had neither a warrior class nor horses.[41][note 4]

Indo-European languages probably spread through language shifts.[42][43] Small groups can change a larger cultural area,[44][2] and elite male dominance by small groups may have led to a language shift in northern India.[45][46][47]

According to Guus Kroonen, Indo-Europeans encountered existing populations that spoke dissimilar, unrelated languages when they migrated to Europe from Yamnaya steppes.[48] Relatively little is known about the Pre-Indo-European linguistic landscape of Europe, except for Basque, as the Indo-Europeanization of Europe caused a largely unrecorded, massive linguistic extinction event, most likely through language-shift.[48] Guus Kroonen's study reveals that PIE speech contains a clear Neolithic signature emanating from the Aegean language family and thus patterns with the prehistoric migration of Europe's first farming populations.[49]

According to Edgar Polomé, 30 % of non-Indo-European substratum found in modern German derives from non-Indo-European-speakers of Funnelbeaker Culture indigenous to southern Scandinavia.[50] When Yamnaya Indo-European speakers came into contact with the indigenous peoples during the third millennium BCE, they came to dominate the local populations yet parts of the indigenous lexicon persisted in the formation of Proto-Germanic, thus lending to the Germanic languages the status of Indo-Europeanized languages.[51] According again to Marija Gimbutas, Corded Ware cultures migration to Scandinavia "synthesized" with the Funnelbeaker culture, giving birth to the Proto-Germanic language.[38]

David Anthony, in his "revised Steppe hypothesis"[52] notes that the spread of the Indo-European languages probably did not happen through "chain-type folk migrations", but by the introduction of these languages by ritual and political elites, which were emulated by large groups of people,[53][note 5] a process which he calls "elite recruitment".[55]

According to Parpola, local elites joined "small but powerful groups" of Indo-European speaking migrants.[42] These migrants had an attractive social system and good weapons, and luxury goods which marked their status and power. Joining these groups was attractive for local leaders, since it strengthened their position, and gave them additional advantages.[56] These new members were further incorporated by matrimonial alliances.[57][43]

According to Joseph Salmons, language shift is facilitated by "dislocation" of language communities, in which the elite is taken over.[58] According to Salmons, this change is facilitated by "systematic changes in community structure", in which a local community becomes incorporated in a larger social structure.[58][note 6]

Genetic relations between historical populations

Since the 2000s genetical studies are assuming a prominent role in the research on Indo-European migrations. Whole-genome studies reveal relations between various cultures and the time-range in which those relations were established. Research by Haak et al. (2015) showed that ~75% of the Corded Ware ancestry came from Yamna-related populations,[13] while Allentoft et al. (2015) shows that the Sintashta culture is genetically related to the Corded Ware culture.[61] Quiles (2017) has proposed a relation between the "expansion of peoples belonging to haplogroup R1b in Eurasia" and the diffusion of Indo-European languages.[62]

Ecological studies: widespread drought, urban collapse, and pastoral migrations

Climate change and drought may have triggered both the initial dispersal of Indo-European speakers, and the migration of Indo-Europeans from the steppes in south central Asia and India.

Around 4200–4100 BCE a climate change occurred, manifesting in colder winters in Europe.[63] Steppe herders, archaic Proto-Indo-European speakers, spread into the lower Danube valley about 4200–4000 BCE, either causing or taking advantage of the collapse of Old Europe.[4]

The Yamna horizon was an adaptation to a climate change which occurred between 3500 and 3000 BCE, in which the steppes became drier and cooler. Herds needed to be moved frequently to feed them sufficiently, and the use of wagons and horse-back riding made this possible, leading to "a new, more mobile form of pastoralism".[64]

In the second millennium BCE widespread aridization lead to water shortages and ecological changes in both the Eurasian steppes and south Asia.[web 13][65] At the steppes, humidization lead to a change of vegetation, triggering "higher mobility and transition to the nomadic cattle breeding".[65][note 7][note 8] Water shortage also had a strong impact in south Asia, "causing the collapse of sedentary urban cultures in south central Asia, Afghanistan, Iran, and India, and triggering large-scale migrations".[web 13]

Origins of the Indo-Europeans

Urheimat

Urheimat hypotheses

The Proto-Indo-European Urheimat hypotheses are tentative identifications of the Urheimat, or primary homeland, of the hypothetical Proto-Indo-European language. Such identifications attempt to be consistent with the glottochronology of the language tree and with the archaeology of those places and times. Identifications are made on the basis of how well, if at all, the projected migration routes and times of migration fit the distribution of Indo-European languages, and how closely the sociological model of the original society reconstructed from Proto-Indo-European lexical items fits the archaeological profile.

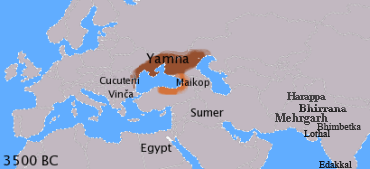

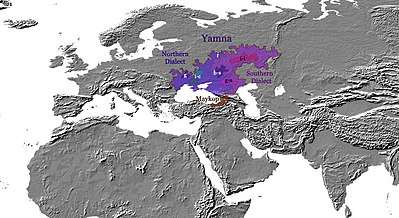

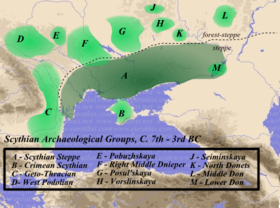

Since the early 1980s[66] the mainstream consensus among Indo-Europeanists favors Marija Gimbutas' "Kurgan hypothesis",[67][68][69][70] c.q. David Anthony's "Revised Steppe theory", derived from Gimbutas' pioneering work,[2] placing the Indo-European homeland in the Pontic steppe, more specifically, between the Dniepr (Ukraine) and the Ural river (Russia), of the Chalcolithic period (4th to 5th millennia BCE),[67] where various related cultures developed.[67][2] The Pontic steppe is a large area of grasslands in far Eastern Europe, located north of the Black Sea, Caucasus Mountains and Caspian Sea and including parts of eastern Ukraine, southern Russia and northwest Kazakhstan. This is the time and place of the earliest domestication of the horse, which according to this hypothesis was the work of early Indo-Europeans, allowing them to expand outwards and assimilate or conquer many other cultures.[2] The Yamna culture (3300–2500 BCE),[2] located on the middle Don and Volga, is the specific culture from where this expansion in its major form started.[2]

The primary competitor is the Anatolian hypothesis advanced by Colin Renfrew,[68][70] which states that the Indo-European languages began to spread peacefully into Europe from Asia Minor (modern Turkey) from around 7000 BCE with the Neolithic advance of farming (wave of advance).[67] Another theory which has drawn considerable attention is the Armenian plateau hypothesis of Gamkrelidze and Ivanov, who have argued that the urheimat was south of the Caucasus, specifically, "within eastern Anatolia, the southern Caucasus and northern Mesopotamia" in the fifth to fourth millennia BCE.[71][67][68][70]

All hypotheses assume a significant period (at least 1500–2000 years) between the time of the Proto-Indo-European language and the earliest attested texts, at Kültepe, c. 19th century BCE.

The Kurgan hypothesis and the "revised steppe theory"

The Kurgan hypothesis (also theory or model) argues that the people of an archaeological "Kurgan culture" (a term grouping the Yamna or Pit Grave culture and its predecessors) in the Pontic steppe were the most likely speakers of the Proto-Indo-European language. The term is derived from kurgan (курган), a Turkic loanword in Russian for a tumulus or burial mound. An origin at the Pontic-Caspian steppes is the most widely accepted scenario of Indo-European origins.[72][73][69][70][note 9]

Marija Gimbutas formulated her Kurgan hypothesis in the 1950s, grouping together a number of related cultures at the Pontic steppes. She defined the "Kurgan culture" as composed of four successive periods, with the earliest (Kurgan I) including the Samara and Seroglazovo cultures of the Dnieper/Volga region in the Copper Age (early 4th millennium BCE). The bearers of these cultures were nomadic pastoralists, who, according to the model, by the early 3rd millennium expanded throughout the Pontic-Caspian steppe and into Eastern Europe.[74]

Gimbutas' grouping is nowadays considered to have been too broad. According to Anthony, it is better to speak of the Yamna culture or of a "Yamna horizon", which included several related cultures, as the defining Proto-Indo-European culture at the Pontic steppe.[2] David Anthony has incorporated recent developments in his "revised steppe theory", which also supports a steppe origin of the Indo-European languages.[2][75] Anthony emphasizes the Yamnaya culture as the origin of the Indo-European dispersal.[2][75] Recent research by Haak et al. (2015) confirms the migration of Yamnaya-people into western Europe, forming the Corded Ware culture.[13]

Proto-Indo-Europeans

The Proto-Indo-Europeans were the speakers of the Proto-Indo-European language (PIE), a reconstructed prehistoric language of Eurasia. Knowledge of them comes chiefly from the linguistic reconstruction, along with material evidence from archaeology and archaeogenetics.

According to some archaeologists, PIE speakers cannot be assumed to have been a single, identifiable people or tribe, but were a group of loosely related populations ancestral to the later, still partially prehistoric, Bronze Age Indo-Europeans. This view is held especially by those archaeologists who posit an original homeland of vast extent and immense time depth. However, this view is not shared by linguists, as proto-languages generally occupy small geographical areas over a very limited time span, and are generally spoken by close-knit communities such as a single small tribe.

The Proto-Indo-Europeans were likely to have lived during the late Neolithic, or roughly the 4th millennium BCE. Mainstream scholarship places them in the forest-steppe zone immediately to the north of the western end of the Pontic-Caspian steppe in Eastern Europe. Some archaeologists would extend the time depth of PIE to the middle Neolithic (5500 to 4500 BCE) or even the early Neolithic (7500 to 5500 BCE), and suggest alternative Proto-Indo-European Urheimats.

By the late third millennium BCE, offshoots of the Proto-Indo-Europeans had reached Anatolia (Hittites), the Aegean (Mycenaean Greece), Western Europe, and southern Siberia (Afanasevo culture).[76]

Pre-Proto-Indo-Europeans

The proto-Indo-Europeans, i. e. the Yamnaya people and the related cultures, seem to have been a mix from eastern European hunter-gatherers; and people related to the near east,[77] i. e. Caucasus hunter-gatherers[78] i. e. Iran Chalcolithic people with a Caucasian hunter-gatherer component.[79][note 10]

According to Haak et al. (2015), "the Yamnaya steppe herders of this time were descended not only from the preceding eastern European hunter-gatherers, but from a population of Near Eastern ancestry."[77]

According to Jones et al. (2015), Caucasus hunter-gatherers (CHG) "genomes significantly contributed to the Yamnaya steppe herders who migrated into Europe ~3,000 BCE, supporting a formative Caucasus influence on this important Early Bronze age culture. CHG left their imprint on modern populations from the Caucasus and also central and south Asia possibly marking the arrival of Indo-Aryan languages."[78][note 11]

According to Lazaridis et al. (2016), "a population related to the people of the Iran Chalcolithic contributed ~ 43 % of the ancestry of early Bronze Age populations of the steppe."[79] These Iranian Chacolithic people were a mixture of "the Neolithic people of western Iran, the Levant, and Caucasus Hunter Gatherers".[79][note 12]

Development of the steppe cultures

Pre-Yamnaya

According to Anthony, the development of the Proto-Indo-European cultures started with the introduction of cattle at the Pontic-Caspian steppes.[81] Until ca. 5200–5000 BCE the Pontic-Caspian steppes were populated by hunter-gatherers.[82] According to Anthony, the first cattle herders arrived from the Danube Valley at ca. 5800–5700 BCE, descendants from the first European farmers.[83] They formed the Criş culture (5800–5300 BCE), creating a cultural frontier at the Prut-Dniestr watershed.[84] The adjacent Bug-Dniester culture (6300–5500 BCE) was a local forager culture, from where cattle breeding spread to the steppe peoples.[85] The Dniepr Rapids area was the next part of the Pontic-Caspian steppes to shift to cattle-herding. It was the densely populated area of the Pontic-Caspian steppes at the time, and had been inhabited by various hunter-gatherer populations since the end of the Ice Age. From ca.5800–5200 it was inhabited by the first phase of the Dnieper-Donets culture, a hunter-gatherer culture contemporaneous with the Bug-Dniestr culture.[86]

At ca. 5200–5000 BCE the non-Indo-European Cucuteni-Tripolye culture (6000–3500 BCE) appears east of the Carpathian mountains, [87] moving the cultural frontier to the Southern Bug valley,[88] while the foragers at the Dniepr Rapids shifted to cattle herding, marking the shift to Dniepr-Donets II (5200/5000 – 4400/4200 BCE).[89] The Dniepr-Donets culture kept cattle not only for ritual sacrifices, but also for their daily diet.[90] The Khvalynsk culture (4700–3800 BCE),[90] located at the middle Volga, which was connected with the Danube Valley by trade networks,[91] also had cattle and sheep, but they were "more important in ritual sacrifices than in the diet".[92] The Samara culture (early 5th millennium BCE),[note 13] north of the Khvalynsk culture, interacted with the Khvalynsk culture,[93] while the archaeological findings seem related to those of the Dniepr-Dontes II Culture.[93]

The Sredny Stog culture (4400–3300 BCE)[94] appears at the same location as the Dniepr-Donets culture, but shows influences from people who came from the Volga river region.[95]

Yamnaya

The Khvalynsk culture (4700–3800 BCE)[90] (middle Volga) and the Don-based Repin culture (ca.3950–3300 BCE)[96] preceded the Yamnaya culture (3300–2500 BCE),[97] which originated in the Don-Volga area.[97] Late pottery from these two cultures can barely be distinguished from early Yamna pottery.[98]

The Yamna horizon was an adaptation to a climate change which occurred between 3500 and 3000 BCE, in which the steppes became drier and cooler. Herds needed to be moved frequently to feed them sufficiently, and the use of wagons and horse-back riding made this possible, leading to "a new, more mobile form of pastoralism".[64] It was accompanied by new social rules and institutions, to regulate the local migrations in the steppes, creating a new social awareness of a distinct culture, and of "cultural Others" who did not participate in these new institutions.[97]

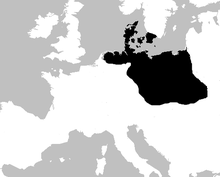

The Yamna culture c.q. horizon (a.k.a. Pit Grave culture) spreads quickly across the Pontic-Caspian steppes between ca. 3400 and 3200 BCE.[99] According to Anthony, "the spread of the Yamnaya horizon was the material expression of the spread of late Proto-Indo-European across the Pontic-Caspian steppes."[100] Anthony further notes that "the Yamnaya horizon is the visible archaeological expression of a social adjustment to high mobility – the invention of the political infrastructure to manage larger herds from mobile homes based in the steppes."[101] The Yamnaya horizon represents the classical reconstructed Proto-Indo-European society with stone idols, predominantly practising animal husbandry in permanent settlements protected by hillforts, subsisting on agriculture, and fishing along rivers. According to Gimbutas, contact of the Yamna culture with late Neolithic Europe cultures results in the "kurganized" Globular Amphora and Baden cultures. Anthony excludes the Globular Amphora culture.[2]

The Maykop culture (3700–3000) emerges somewhat earlier in the northern Caucasus. Although considered by Gimbutas as an outgrowth of the steppe cultures, it is related to the development of Mesopotamia, and Anthony does not consider it to be a Proto-Indo-European culture.[2] The Maykop culture shows the earliest evidence of the beginning Bronze Age, and Bronze weapons and artifacts are introduced to the Yamna horizon.

Between 3100–2600 BCE Yamna people into the Danube Valley as far as Hungary.[102] This migration probably gave rise to Proto-Celtic[103] and Pre-Italic.[103] Pre-Germanic dialects may have developed between the Dniestr (west Ukraine) and the Vistula (Poland) at c. 3100–2800 BCE, and spread with the Corded Ware culture.[104] Slavic and Baltic developed at the middle Dniepr (present-day Ukraine)[10] at c. 2800 BCE, also spreading with the Corded Ware horizon.[36]

Post-Yamnaya

In the northern Don-Volga area the Yamnaya culture was followed by the Poltavka culture (2700–2100 BCE), while the Sintashta culture (2100–1800) extended the Indo-European culture zone east of the Ural mountains, giving rise to Proto-Indo-Iranian and the subsequent spread of the Indo-Iranian languages toward India and the Iranian plateau.[2]

Early migrations: Archaic Proto-Indo-European

Europe and Anatolia (5th–4th millennium BCE)

Europe: Migration into the Danube Valley (4200 BCE)

According to Anthony, steppe herders, archaic Proto-Indo-European speakers, spread into the lower Danube valley about 4200–4000 BCE, either causing or taking advantage of the collapse of Old Europe.[4] According to Anthony, their languages "probably included archaic Proto-Indo-European dialects of the kind partly preserved later in Anatolian."[105] According to Anthony their descendants later moved into Anatolia, at an unknown time, but maybe as early as 3,000 BCE.[5] According to Mathieson & Reich et al. (2017), it is unlikely that the Anatolian branch arrived in Anatolia via the Balkans.[31]

According to Parpola, the appearance of Indo-European speakers from Europe into Anatolia, and the appearance of Hittite, is related to later migrations of Proto-Indo-European speakers from the Yamna-culture into the Danube Valley at ca. 2800 BCE,[30][9] which is in line with the "customary" assumption that the Anatolian Indo-European language was introduced into Anatolia somewhere in the third millennium BCE.[web 1]

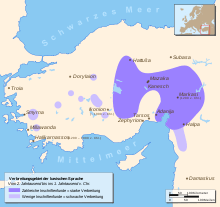

Anatolia: Archaic Proto-Indo-European (Hittites; 4500–3500 BCE)

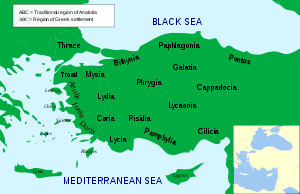

The Anatolians were a group of distinct Indo-European peoples who spoke the Anatolian languages and shared a common culture.[106][107][108][109][110] The Anatolian languages were a branch of the larger Indo-European language family.

Although the Hittites are placed in the 2nd millennium BCE,[29] the Anatolian branch seems to have separated at a very early stage from Proto-Indo-European, or may have developed from an older Pre-Proto-Indo-European ancestor.[111] If it separated from Proto-Indo-European, it likely did so between 4500–3500 BCE.[112]

The archaeological discovery of the archives of the Hittites and the belonging of the Hittite language to a separate Anatolian branch of the Indo-European languages caused a sensation among historians, forcing a re-evaluation of Near Eastern history and Indo-European linguistics.[110] In accordance with the Kurgan hypothesis, J. P. Mallory notes in Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture that it is likely that the Anatolians reached the Near East from the north, either via the Balkans or the Caucasus in the 3rd millennium BCE.[110] According to Anthony, descendants of archaic Proto-Indo-European steppe herders, who moved into the lower Danube valley about 4200–4000 BCE, later moved into Anatolia, at an unknown time, but maybe as early as 3,000 BCE.[113] According to Parpola the movement into Anatolia took place at a later date.[30] According to Mathieson & Reich et al. (2017), it is unlikely that the Anatolian branch arrived in Anatolia via the Balkans.[31]

Together with the Tocharians, the Anatolians constituted the first known wave of Indo-European emigrants out of the Eurasian steppe.[114] Although they had wagons, they probably emigrated before Indo-Europeans had learned to use chariots for war.[114] It is likely that their arrival was one of gradual settlement and not as an invading army.[106] The Anatolians' earliest linguistic and historical attestation are as names mentioned in Assyrian mercantile texts from 19th-century BCE Kanesh.[106]

The Hittites, who established an extensive empire in the Middle East in the 2nd millennium BCE, are by far the best known members of the Anatolian group. The history of the Hittite civilization is known mostly from cuneiform texts found in the area of their kingdom, and from diplomatic and commercial correspondence found in various archives in Egypt and the Middle East. Despite the use of Hatti for their core territory, the Hittites should be distinguished from the Hattians, an earlier people who inhabited the same region (until the beginning of the 2nd millennium). The Hittite military made successful use of chariots. Although belonging to the Bronze Age, they were the forerunners of the Iron Age, developing the manufacture of iron artifacts from as early as the 14th century, when letters to foreign rulers reveal the latter's demand for iron goods. The Hittite empire reached its height during the mid-14th century under Suppiluliuma I, when it encompassed an area that included most of Asia Minor as well as parts of the northern Levant and Upper Mesopotamia. After 1180 BCE, amid the Bronze Age Collapse in the Levant associated with the sudden arrival of the Sea Peoples, the kingdom disintegrated into several independent "Neo-Hittite" city-states, some of which survived until as late as the 8th century BCE. The lands of the Anatolian peoples were successively invaded by a number of peoples and empires at high frequency: the Phrygians, Bithynians, the Medes, the Persians, the Greeks, the Galatian Celts, Romans and the Oghuz Turks. Many of these invaders settled in Anatolia, in some cases causing the extinction of the Anatolian languages. By the Middle Ages, all the Anatolian languages (and the cultures accompanying them) were extinct, although there may be lingering influences on the modern inhabitants of Anatolia, most notably Armenians.

Northern Caucasus: The Maykop culture (3700–3000 BCE)

The Maykop culture (also spelled Maikop), c. 3700–3000 BCE,[115] was a major Bronze Age archaeological culture in the Western Caucasus region of Southern Russia. It extends along the area from the Taman Peninsula at the Kerch Strait to near the modern border of Dagestan and southwards to the Kura River. The culture takes its name from a royal burial found in Maykop kurgan in the Kuban River valley.

According to Mallory and Adams, migrations southward founded the Maykop culture (c. 3500–2500 BCE).[34] Yet, according to Mariya Ivanova the Maykop origins were on the Iranian Plateau,[35] while kurgans from the beginning of the 4th millennium at Soyuqbulaq in Azerbaijan, which belong to the Leyla-Tepe culture, show parallels with the Maykop kurgans. According to Museyibli, "the Leylatepe Culture tribes migrated to the north in the mid-fourth millennium and played an important part in the rise of the Maikop Culture of the North Caucasus."[web 10]

Asia (3500–2500 BCE)

Afanasevo culture

The Afanasievo culture (3300 to 2500 BCE) is the earliest Eneolithic archaeological culture found until now in south Siberia, occupying the Minusinsk Basin, Altay and Eastern Kazakhstan. It originated with a migration of people from the pre-Yamnaya Repin culture, at the Don river,[96] and is related to the Tocharians.[116]

Radiocarbon gives dates as early as 3705 BCE on wooden tools and 2874 BCE on human remains for the Afanasievo culture.[web 14] The earliest of these dates has now been rejected, giving a date of around 3300 BCE for the start of the culture.[117]

The Tocharians

The Tocharians, or "Tokharians" (/təˈkɛəriənz/ or /təˈkɑːriənz/) were inhabitants of medieval oasis city-states on the northern edge of the Tarim Basin (modern Xinjiang, China). Their Tocharian languages (a branch of the Indo-European family) are known from manuscripts from the 6th to 8th centuries CE, after which they were supplanted by the Turkic languages of the Uyghur tribes. These people were called "Tocharian" by late 19th-century scholars who identified them with the Tókharoi described by ancient Greek sources as inhabiting Bactria. Although this identification is now generally considered mistaken, the name has become customary.

The Tocharians are thought to have developed from the Afanasevo culture of eastern Siberia (c. 3500–2500 BCE).[116] It is believed that the Tarim mummies, dated from 1800 BCE, represent a migration of Tocharian speakers from the Afanasevo culture in the Tarim Basin in the early 2nd millennium BCE.[33] By the end of the 2nd millennium BCE, the dominant people as far east as the Altai Mountains southward to the northern outlets of the Tibetan Plateau were anthropologically Caucasian, with the northern part speaking Iranian Scythian languages and the southern parts Tocharian languages, having Mongoloid populations as their northeastern neighbors.[118][119] These two groups were in competition with each other until the latter overcame the former.[119] The turning point occurred around the 5th to 4th centuries BCE with a gradual Mongolization of Siberia, while Eastern Central Asia (East Turkistan) remained Caucasian and Indo-European-speaking until well into the 1st millennium CE.[120]

The Sinologist Edwin G. Pulleyblank has suggested that the Yuezhi, the Wusun the Dayuan, the Kangju and the people of Yanqi, could have been Tocharian-speaking.[121] Of these the Yuezhi are generally held to have been Tocharians.[122] The Yuezhi were originally settled in the arid grasslands of the eastern Tarim Basin area, in what is today Xinjiang and western Gansu, in China. After the Yuezhi were defeated by the Xiongnu, in the 2nd century BCE, a small group, known as the Little Yuezhi, fled to the south, later spawning the Jie people who dominated the Later Zhao until their complete extermination by Ran Min in the Wei–Jie war. The majority of the Yuezhi however migrated west to the Ili Valley, where they displaced the Sakas (Scythians). Driven from the Ili Valley shortly afterwards by the Wusun, the Yuezhi migrated to Sogdia and then Bactria, where they are often identified with the Tókharoi (Τοχάριοι) and Asioi of Classical sources. They then expanded into northern South Asia, where one branch of the Yuezhi founded the Kushan Empire. The Kushan empire stretched from Turfan in the Tarim Basin to Pataliputra on the Gangetic plain at its greatest extent, and played an important role in the development of the Silk Road and the transmission of Buddhism to China. Tocharian languages continued to be spoken in the city-states of the Tarim Basin, only becoming extinct in the Middle Ages.

Europe

Origins of the European IE languages

Mallory notes that the Italic, Celtic and Germanic languages are closely related, which accords with their historic distribution. The Germanic languages are also related to the Baltic and Slavic languages, which in turn share similarities with the Indo-Iranic languages.[123] The Greek, Armenian and Indo-Iranian languages are also related, which suggests "a chain of central Indo-European dialects stretching from the Balkans across the Black sea to the east Caspian".[123] And the Celtic, Italic, Anatolian and Tocharian languages preserve archaisms which are preserved only in those languages.[123] According to David Anthony, pre-Germanic split-off earliest (3300 BCE), followed by pre-Italic and pre-Celtic (3000 BCE), pre-Armenian (2800 BCE), pre-Balto-Slavic (2800 BCE) and pre-Greek (2500 BCE).[26]

Three autosomal genetic studies in 2015 gave support to the Kurgan hypothesis of Gimbutas regarding the proto-Indo-European homeland. According to those studies, haplogroups R1b and R1a would have expanded from the West Eurasian Steppe, along with the Indo-European languages; they also detected an autosomal component present in modern Europeans which was not present in Neolithic Europeans, which would have been introduced with paternal lineages R1b and R1a, as well as Indo-European Languages.[124][125][126]

The Balkan-Danubian complex and the Dniestr and Dniepr rivers

| Dniestr, Vistula, Dniepr |

|---|

Dniester river |

Vistula river |

Dniepr river |

The Balkan-Danubian complex is a set of cultures in Southeast Europe from which the western Indo-European languages probably spread into western Europe from c. 3500 BCE.[8] According to Anthony, Pre-Italic, Pre-Celtic and Pre-Germanic may have split-off here from Proto-Indo-European.[127]

The Usatovo culture developed in south-eastern Central Europe at around 3300–3200 BCE at the Dniestr river.[128] Although closely related to the Tripolye culture, it is contemporary with the Yamna culture, and resembles it in significant ways.[129] According to Anthony, it may have originated with "steppe clans related to the Yamnaya horizon who were able to impose a patron-client relationship on Tripolye farming villages".[130]

According to Anthony, the Pre-Germanic dialects may have developed in this culture between the Dniestr (west Ukraine) and the Vistula (Poland) at c. 3100–2800 BCE, and spread with the Corded Ware culture.[104]

Between 3100–2800/2600 BCE, when the Yamna horizon spread fast across the Pontic Steppe, a real folk migration of Proto-Indo-European speakers from the Yamna-culture took place into the Danube Valley,[9] moving along Usatovo territory toward specific destinations, reaching as far as Hungary,[131] where as many as 3,000 kurgans may have been raised.[132] Bell Beaker sites at Budapest, dated c. 2800–2600 BCE, may have aided in spreading Yamna dialects into Austria and southern Germany at their west, where Proto-Celtic may have developed.[103] Pre-Italic may have developed in Hungary, and spread toward Italy via the Urnfield culture and Villanovan culture.[103] According to Anthony, Slavic and Baltic developed at the middle Dniepr (present-day Ukraine)[10] at c. 2800 BCE, spreading north from there.[36]

According to Parpola, this migration into the Danube Valley is related to the appearance of Indo-European speakers from Europe into Anatolia, and the appearance of Hittite.[30]

The Balkan languages (Thracian, Dacian, Illyrian) may have developed among of the early Indo-European populations of southeastern Europe. In the early Middle Ages their territory was occupied by migrating Slavic people, and by east Asian steppe peoples.

Corded Ware culture (3000–2400 BCE)

The Corded Ware culture in Middle Europe (c. 3200[133] or 2,900[web 2]–2450 or 2350 cal.[web 2][133] BCE) is hypothesized to have played an essential role in the origin and spread of the Indo-European languages in Europe during the Copper and Bronze Ages.[11][12] David Anthony states that "Childe (1953:133-38) and Gimbutas (1963) speculated that migrants from the steppe Yamnaya culture (3300–2600 BCE) might have been the creators of the Corded Ware culture and carried IE languages into Europe from the steppes."[134] According to Gimbutas, the Corded Ware culture was preceded by the Globular Amphora culture (3400–2800 BCE), which she also regarded to be an Indo-European culture. The Globular Amphora culture stretched from central Europe to the Baltic sea, and emerged from the Funnelbeaker culture.[135]

According to Mallory, the Corded Ware culture may be postulated as "the common prehistoric ancestor of the later Celtic, Germanic, Baltic, Slavic, and possibly some of the Indo-European languages of Italy". Yet, Mallory also notes that the Corded Ware can not account for Greek, Illyrian, Thracian and East Italic, which may be derived from Southeast Europe.[136] According to Anthony, the Corded ware horizon may have introduced Germanic, Baltic and Slavic into northern Europe.[103]

The Corded Ware spread across northern Europe after 3000 BCE, with an "initial rapid spread" between 2900 and 2700 BCE.[103] Around 2400 BCE the people of the Corded Ware replaced their predecessors and expanded to Danubian and Nordic areas of western Germany. A related branch invaded Denmark and southern Sweden. In places a continuity between Funnelbeaker and Corded Ware can be demonstrated, whereas in other areas Corded Ware heralds a new culture and physical type.[137] According to Cunliffe, most of the expansion was clearly intrusive.[138] Yet, according to Furholt, the Corded Ware culture was an indigenous development,[134] connecting local developments into a larger network.[139]

Recent research by Haak et al. found that four late Corded Ware people (2500–2300 BCE) buried at Esperstadt, Germany, were genetically very close to the Yamna-people, stating that a massive migration took place from the Eurasian steppes to Central Europe.[13][web 3][web 4][140] Haak et al. (2015) note that German Corded ware "trace ~75% of their ancestry to the Yamna,"[141] envisioning a migration of both males and females from the Yamna culture through western Ukraine and Poland into Germany.[142] Allentoft et al. (2015) envision a migration from the Yamna culture towards northern Europe, both via Central Europe and the territory of present-day Russia, toward the Baltic area and the eastern periphery of the Corded ware culture.[143] In supplementary information to Haak et al. (2015) Anthony, together with Lazaridis, Haak, Patterson, and Reich, notes that the mass migration of Yamna people to northern Europe shows that "the languages could have been introduced simply by strength of numbers: via major migration in which both sexes participated."[144][note 14]

Anthony (2017) relates these close genetical similarities, and the development of the Corded ware culture, to the early third century Yamna-migrations into the Danube-valley, stating that "[t]he migration stream that created these intrusive cemeteries now can be seen to have continued from eastern Hungary across the Carpatians into southern Poland, where the earlies material traits of the Corded ware horizon appeared."[139][note 15]

Volker Heyd has cautioned to be careful with drawing too strong conclusions from those genetic similarities between Corded Ware and Yamna, noting the small number of samples; the late dates of the Esperstadt graves, which could also have undergone Bell Beaker admixture; the presence of Yamna-ancestry in western Europe before the Danube-expansion; and the risks of extrapolating "the results from a handful of individual burials to whole ethnically interpreted populations."[145] Heyd confirms the close connection between Corded Ware and Yamna, but also states that "neither a one-to-one translation from Yamnaya to CWC, nor even the 75:25 ratio as claimed (Haak et al. 2015:211) fits the archaeological record."[145]

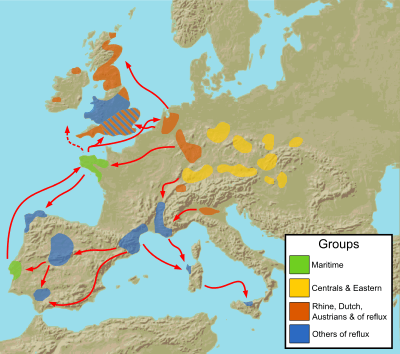

Beaker culture (2900–1800 BCE)

The Bell Beaker-culture (c. 2900–1800 BCE[147][148]) may have spread proto-Celtic.[149] More recently Mallory has suggested that the Beaker culture was associated with a European branch of Indo-European dialects, termed "North-west Indo-European", ancestral to not only Celtic but equally Italic, Germanic and Balto-Slavic.[14][note 16]

The initial moves from the Tagus estuary were maritime. A southern move led to the Mediterranean where 'enclaves' were established in south-western Spain and southern France around the Golfe du Lion and into the Po valley in Italy, probably via ancient western Alpine trade routes used to distribute jadeite axes. A northern move incorporated the southern coast of Armorica. The enclave established in southern Brittany was linked closely to the riverine and landward route, via the Loire, and across the Gâtinais valley to the Seine valley, and thence to the lower Rhine. This was a long-established route reflected in early stone axe distributions and it was via this network that Maritime Bell Beakers first reached the Lower Rhine in about 2600 BCE.[148][150]

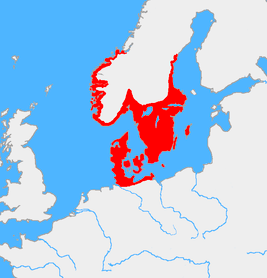

Germanic

.png)

The Germanic peoples (also called Teutonic, Suebian or Gothic in older literature)[151] are an Indo-European ethno-linguistic group of Northern European origin, identified by their use of the Germanic languages which diversified out of Proto-Germanic starting during the Pre-Roman Iron Age.[web 15]

The term "Germanic" originated in classical times, when groups of tribes were referred to using this term by Roman authors. For them, the term was not necessarily based upon language, but rather referred to tribal groups and alliances who were considered less civilised than the Celtic Gauls living in the region of modern France. Tribes referred to as Germanic in that period lived generally to the north and east of the Gauls with the Rhine as a approximate border line.

In modern times the term occasionally has been used to refer to ethnic groups who speak a Germanic language and claim ancestral and cultural connections to ancient Germanic peoples.[152] Within this context, modern Germanic peoples include the Norwegians, Swedes, Danes, Icelanders, Germans, Austrians, English, Dutch, Afrikaners, Flemish, Frisians and others.[153][154][web 16]

The Germanic languages are spoken by a sizable population in Western Europe, North America, and Australasia. The common ancestor of all of the languages in this branch is called Proto-Germanic (also known as Common Germanic), which was spoken in approximately the middle of the 1st millennium BCE in Iron Age northern Europe. Proto-Germanic, along with all of its descendants, is characterized by a number of unique linguistic features, most famously the consonant change known as Grimm's law. Early varieties of Germanic enter history with the Germanic tribes moving south from northern Europe in the 2nd century BCE, to settle in north-central Europe.

The most widely spoken Germanic languages are English and German, with approximately 300–400 million native English speakers[web 17][155] and over 100 million native German speakers.[156] They belong to the West Germanic family. The West Germanic group also includes other major languages, such as Dutch with 23 million,[web 18] Low Saxon with approximately 5 million speakers in Germany[web 19] and 1.7 million in the Netherlands,[157] and Afrikaans with over 6 million native speakers.[158] The North Germanic languages include Norwegian, Danish, Swedish, Icelandic, and Faroese, which have a combined total of about 20 million speakers.[159] There is also the East Germanic branch, which includes languages such as Gothic, Burgundian, and Vandalic, but it has been extinct for at least two centuries. The SIL Ethnologue lists 48 different living Germanic languages, with the Western branch accounting for 42, and the Northern for 6 languages.[160] The total number of Germanic languages is unknown, as some of them, especially East Germanic languages, disappeared shortly after the Migration Period.

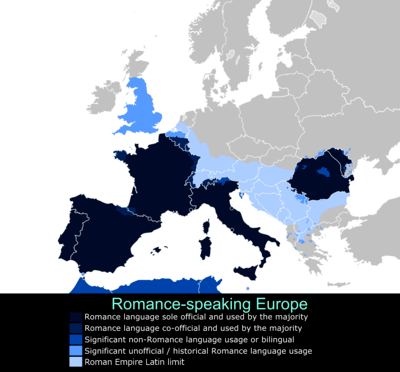

Italic and Celtic

Italic

The Italic languages are a subfamily of the Indo-European language family originally spoken by Italic peoples. They include the Romance languages derived from Latin (Italian, Sardinian, Spanish, Catalan, Portuguese, French, Romanian, Occitan, etc.); a number of extinct languages of the Italian Peninsula, including Umbrian, Oscan, Faliscan, South Picene; and Latin itself. At present, Latin and its daughter Romance languages are the only surviving languages of the Italic language family.

The most widely accepted theory suggests that Latins and other proto-Italic tribes first entered in Italy with the late Bronze Age Proto-Villanovan culture, then part of the central European Urnfield culture system.[161][162] In particular various authors, like Marija Gimbutas, had noted important similarities between Proto-Villanova, the South-German Urnfield culture of Bavaria-Upper Austria[163] and Middle-Danube Urnfield culture.[163][164][165] According to David W. Anthony, proto-Latins originated in today's eastern Hungary, kurganized around 3100 BCE by the Yamna culture,[166] while Kristian Kristiansen associated the Proto-Villanovans with the Velatice-Baierdorf culture of Moravia and Austria.[167]

Today the Romance languages, which comprise all languages that descended from Latin, are spoken by more than 800 million native speakers worldwide, mainly in the Americas, Europe, and Africa. Romance languages are either official, co-official, or significantly used in 72 countries around the globe.[168][169][170][171][172][173]

Additionally, Latin had a great influence on both the grammar and the lexicon of West Germanic languages. Romance words make respectively 59 %, 20 % and 14 % of English, German and Dutch vocabularies.[174][175][176] Those figures can rise dramatically when only non-compound and non-derived words are included. Accordingly, Romance words make roughly 35% of the vocabulary of Dutch.[176]

Celtic

The Celts (/ˈkɛlts/, occasionally /ˈsɛlts/, see pronunciation of Celtic) or Kelts were an ethnolinguistic group of tribal societies in Iron Age and Medieval Europe who spoke Celtic languages and had a similar culture,[177] although the relationship between the ethnic, linguistic and cultural elements remains uncertain and controversial.

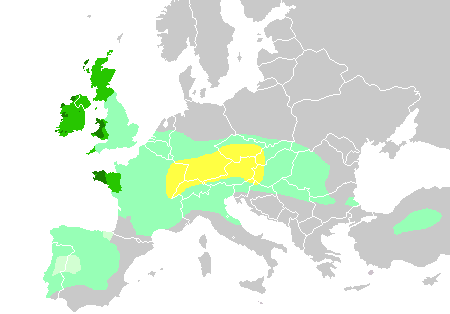

The earliest archaeological culture that may justifiably be considered Proto-Celtic is the Late Bronze Age Urnfield culture of Central Europe, which flourished from around 1200 BCE.[178] Their fully Celtic[178] descendants in central Europe were the people of the Iron Age Hallstatt culture (c. 800–450 BCE) named for the rich grave finds in Hallstatt, Austria.[179] By the later La Tène period (c. 450 BCE up to the Roman conquest), this Celtic culture had expanded by diffusion or migration to the British Isles (Insular Celts), France and The Low Countries (Gauls), Bohemia, Poland and much of Central Europe, the Iberian Peninsula (Celtiberians, Celtici and Gallaeci) and Italy (Golaseccans, Lepontii, Ligures and Cisalpine Gauls)[180] and, following the Gallic invasion of the Balkans in 279 BCE, as far east as central Anatolia (Galatians).[181]

The Celtic languages (usually pronounced /ˈkɛltɪk/ but sometimes /ˈsɛltɪk/)[182] are descended from Proto-Celtic, or "Common Celtic"; a branch of the greater Indo-European language family. The term "Celtic" was first used to describe this language group by Edward Lhuyd in 1707.[183]

Modern Celtic languages are mostly spoken on the north-western edge of Europe, notably in Ireland, Scotland, Wales, Brittany, Cornwall, and the Isle of Man, and can be found spoken on Cape Breton Island. There are also a substantial number of Welsh speakers in the Patagonia area of Argentina. Some people speak Celtic languages in the other Celtic diaspora areas of the United States,[184] Canada, Australia,[185] and New Zealand.[186] In all these areas, the Celtic languages are now only spoken by minorities though there are continuing efforts at revitalization. Welsh is the only Celtic language not classified as "endangered" by UNESCO.

During the 1st millennium BCE, they were spoken across much of Europe, in the Iberian Peninsula, from the Atlantic and North Sea coastlines, up to the Rhine valley and down the Danube valley to the Black Sea, the northern Balkan Peninsula and in central Asia Minor. The spread to Cape Breton and Patagonia occurred in modern times. Celtic languages, particularly Irish, were spoken in Australia before federation in 1901 and are still used there to some extent.[187]

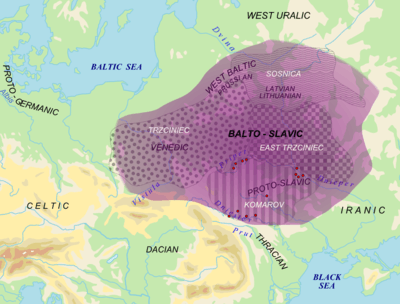

Balto-Slavic

The Balto-Slavic language group traditionally comprises the Baltic and Slavic languages, belonging to the Indo-European family of languages. Baltic and Slavic languages share several linguistic traits not found in any other Indo-European branch, which points to a period of common development. Most Indo-Europeanists classify Baltic and Slavic languages into a single branch, even though some details of the nature of their relationship remain in dispute[note 17] in some circles, usually due to political controversies.[188] Some linguists, however, have recently suggested that Balto-Slavic should be split into three equidistant nodes: Eastern Baltic, Western Baltic and Slavic.[note 18][note 19]

A Proto-Balto-Slavic language is reconstructable by the comparative method, descending from Proto-Indo-European by means of well-defined sound laws, and out of which modern Slavic and Baltic languages descended. One particularly innovative dialect separated from the Balto-Slavic dialect continuum and became ancestral to the Proto-Slavic language, from which all Slavic languages descended.[189]

Balts

The Balts or Baltic peoples (Lithuanian: baltai, Latvian: balti) are an Indo-European ethno-linguistic group who speak the Baltic languages, a branch of the Indo-European language family, which was originally spoken by tribes living in area east of Jutland peninsula in the west and Moscow, Oka and Volga rivers basins in the east. One of the features of Baltic languages is the number of conservative or archaic features retained.[190] Among the Baltic peoples are modern Lithuanians, Latvians (including Latgalians) – all Eastern Balts – as well as the Old Prussians, Yotvingians and Galindians – the Western Balts – whose people also survived, but their languages and cultures are now extinct, and are now being assimilated into the Eastern Baltic community.

Slavs

The Slavs are an Indo-European ethno-linguistic group living in Central Europe, Eastern Europe, Southeast Europe, North Asia and Central Asia, who speak the Indo-European Slavic languages, and share, to varying degrees, certain cultural traits and historical backgrounds. From the early 6th century they spread to inhabit most of Central and Eastern Europe and Southeast Europe. Slavic groups also ventured as far as Scandinavia, constituting elements amongst the Vikings;[191][note 20] whilst at the other geographic extreme, Slavic mercenaries fighting for the Byzantines and Arabs settled Asia Minor and even as far as Syria.[192] Later, East Slavs (specifically, Russians and Ukrainians) colonized Siberia[193] and Central Asia.[194] Every Slavic ethnicity has emigrated to other parts of the world.[195][196] Over half of Europe's territory is inhabited by Slavic-speaking communities.[197]

Modern nations and ethnic groups called by the ethnonym Slavs are considerably diverse both genetically and culturally, and relations between them – even within the individual ethnic groups themselves – are varied, ranging from a sense of connection to mutual feelings of hostility.[198]

Present-day Slavic people are classified into East Slavic (chiefly Belarusians, Russians and Ukrainians), West Slavic (chiefly Poles, Czechs, Slovaks, Wends and Sorbs), and South Slavic (chiefly Bosniaks, Bulgarians, Croats, Goranis, Macedonians, Montenegrins, Serbs and Slovenes).[199] For a more comprehensive list, see the ethnocultural subdivisions.

Balkan languages

Thracian and Dacian

Thracian

The Thracian language was the Indo-European language spoken in Southeast Europe by the Thracians, the northern neighbors of the Greeks. Some authors group Thracian and Dacian into a southern Baltic linguistic family.[200] The Thracians inhabited a large area in southeastern Europe,[201] including parts of the ancient provinces of Thrace, Moesia, Macedonia, Dacia, Scythia Minor, Sarmatia, Bithynia, Mysia, Pannonia, and other regions of the Balkans and Anatolia. This area extended over most of the Balkans region, and the Getae north of the Danube as far as beyond the Bug and including Panonia in the west.[202]

The origins of the Thracians remain obscure, in the absence of written historical records. Evidence of proto-Thracians in the prehistoric period depends on artifacts of material culture. Leo Klejn identifies proto-Thracians with the multi-cordoned ware culture that was pushed away from Ukraine by the advancing timber grave culture. It is generally proposed that a proto-Thracian people developed from a mixture of indigenous peoples and Indo-Europeans from the time of Proto-Indo-European expansion in the Early Bronze Age[203] when the latter, around 1500 BCE, mixed with indigenous peoples.[204] We speak of proto-Thracians from which during the Iron Age[205] (about 1000 BCE) Dacians and Thracians begin developing.

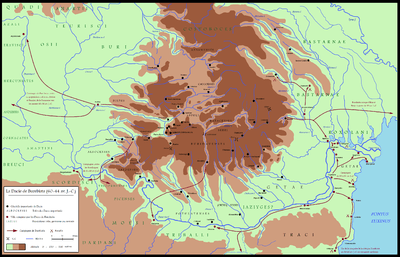

Dacian

The Dacians (/ˈdeɪʃənz/; Latin: Daci, Ancient Greek: Δάκοι,[206] Δάοι,[206] Δάκαι[207]) were an Indo-European people, part of or related to the Thracians. Dacians were the ancient inhabitants of Dacia, located in the area in and around the Carpathian Mountains and west of the Black Sea. This area includes the present-day countries of Romania and Moldova, as well as parts of Ukraine,[208] Eastern Serbia, Northern Bulgaria, Slovakia,[209] Hungary and Southern Poland.[208]

The Dacians spoke the Dacian language, believed to have been closely related to Thracian, but were somewhat culturally influenced by the neighbouring Scythians and by the Celtic invaders of the 4th century BCE.[web 20] The Dacians and Getae were always considered as Thracians by the ancients (Dio Cassius, Trogus Pompeius, Appian, Strabo and Pliny the Elder), and were both said to speak the same Thracian language.[210][211]

Evidence of proto-Thracians or proto-Dacians in the prehistoric period depends on the remains of material culture. It is generally proposed that a proto-Dacian or proto-Thracian people developed from a mixture of indigenous peoples and Indo-Europeans from the time of Proto-Indo-European expansion in the Early Bronze Age (3,300–3,000 BCE)[203] when the latter, around 1500 BCE, conquered the indigenous peoples.[204] The indigenous people were Danubian farmers, and the invading people of the 3rd millennium BCE were Kurgan warrior-herders from the Ukrainian and Russian steppes.[212]

Indo-Europeanization was complete by the beginning of the Bronze Age. The people of that time are best described as proto-Thracians, which later developed in the Iron Age into Danubian-Carpathian Geto-Dacians as well as Thracians of the eastern Balkan Peninsula.[213]

Illyrian

.jpg)

The Illyrians (Ancient Greek: Ἰλλυριοί, Illyrioi; Latin: Illyrii or Illyri) were a group of Indo-European tribes in antiquity, who inhabited part of the western Balkans and the south-eastern coasts of the Italian peninsula (Messapia).[215] The territory the Illyrians inhabited came to be known as Illyria to Greek and Roman authors, who identified a territory that corresponds to the Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Slovenia, Montenegro, part of Serbia and most of Albania, between the Adriatic Sea in the west, the Drava river in the north, the Morava river in the east and the mouth of the Aoos river in the south.[216] The first account of Illyrian peoples comes from the Periplus of Pseudo-Scylax, an ancient Greek text of the middle of the 4th century BCE that describes coastal passages in the Mediterranean.[217]

These tribes, or at least a number of tribes considered "Illyrians proper", of which only small fragments are attested enough to classify as branches of Indo-European;[218] were probably extinct by the 2nd century CE.[219]

The name "Illyrians", as applied by the ancient Greeks to their northern neighbors, may have referred to a broad, ill-defined group of peoples, and it is today unclear to what extent they were linguistically and culturally homogeneous. The Illyrian tribes never collectively regarded themselves as 'Illyrians', and it is unlikely that they used any collective nomenclature for themselves.[220] The name Illyrians seems to be the name applied to a specific Illyrian tribe, which was the first to come in contact with the ancient Greeks during the Bronze Age,[221] causing the name Illyrians to be applied to all people of similar language and customs.[222]

Albanian

Albanian (shqip [ʃcip] or gjuha shqipe [ˈɟuha ˈʃcipɛ], meaning Albanian language) is an Indo-European language spoken by approximately 7.4 million people, primarily in Albania, Kosovo, the Republic of Macedonia and Greece, but also in other areas of the Balkans in which there is an Albanian population, including Montenegro and Serbia (Presevo Valley). Centuries-old communities speaking Albanian-based dialects can be found scattered in Greece, southern Italy,[223] Sicily, and Ukraine.[224] As a result of a modern diaspora, there are also Albanian speakers elsewhere in those countries and in other parts of the world, including Scandinavia, Switzerland, Germany, Austria and Hungary, United Kingdom, Turkey, Australia, New Zealand, Netherlands, Singapore, Brazil, Canada, and the United States.

The earliest written document that mentions the Albanian language is a late 13th-century crime report from Dubrovnik. The first audio recording of the Albanian language was made by Norbert Jokl on 4 April 1914 in Vienna.[225]

Armenic and Greek

Armenian

The Armenian Highland lies in the highlands surrounding Mount Ararat, the highest peak of the region. In the Bronze Age, several states flourished in the area of Greater Armenia, including the Hittite Empire (at the height of its power), Mitanni (South-Western historical Armenia), and Hayasa-Azzi (1600–1200 BCE). Soon after Hayasa-Azzi were the Nairi (1400–1000 BCE) and the Kingdom of Urartu (1000–600 BCE), who successively established their sovereignty over the Armenian Highland. Each of the aforementioned nations and tribes participated in the ethnogenesis of the Armenian people.[226] Yerevan, the modern capital of Armenia, was founded in 782 BCE by king Argishti I.

A minority view also suggests that the Indo-European homeland may have been located in the Armenian Highland.[227]

Hellenic Greek

Hellenic is the branch of the Indo-European language family that includes the different varieties of Greek.[229] In traditional classifications, Hellenic consists of Greek alone,[230][231] but some linguists group Greek together with various ancient languages thought to have been closely related or distinguish varieties of Greek that are distinct enough to be considered separate languages.[232][233]

The Proto-Greeks, who spoke the predecessor of the Mycenaean language, are mostly placed in the Early Helladic period in Greece (early 3rd millennium BCE; circa 3200 BCE) towards the end of the Neolithic in Southern Europe.[234][235]

Sea Peoples and the Bronze Age Collapse

In the 13th century BCE, at the end of the Bronze Age, seafaring invaders from Europe and the Aegean, known as the Sea Peoples, entered the Eastern Mediterranean, invading Anatolia, Syria, Canaan, Cyprus and Egypt.[236][237] The invasions by the Sea Peoples ushered the Bronze Age Collapse, which resulted in the cultural collapse of Mycenean Greece, the Hittite Empire, the New Kingdom of Egypt and the civilizations of Canaan and Syria. The Sea Peoples are regarded as being composed of various groups of Indo-European[238] and non-Indo-European peoples.

Groups of the Sea Peoples mentioned in Egyptian documents are the Ekwesh, a group of Bronze Age Greeks (Achaeans, called Ahhiyawa in Hittite texts); Teresh (Tyrsenoi), known to later Greeks as sailors and pirates from Anatolia, ancestors of the Etruscans; Luka, an Anatolian coastal people of western Anatolia, also known from Hittite sources (their name survives in classical Lycia on the southwest coast of Anatolia); Sherden, probably Sardinians (the Sherden acted as mercenaries of the Egyptians in the Battle of Kadesh, 1299 BCE); Shekelesh, probably identical with the Italic tribe called Siculi; and Peleset, generally believed to refer to the Philistines, who perhaps came from Crete and were the only major tribe of the Sea Peoples to settle permanently in Palestine.[237]

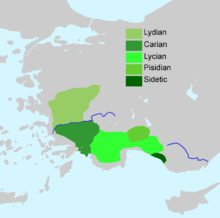

Phrygian

The Phrygians (gr. Φρύγες, Phrúges or Phrýges) were an ancient Indo-European people. After the collapse of the Hittite Empire at the beginning of the twelfth century BCE, the political vacuum in central-western Anatolia was filled by a wave of Indo-European migrants and "Sea Peoples", including the Phrygians, who established their kingdom with a capital eventually at Gordium. It is presently unknown whether the Phrygians were actively involved in the collapse of the Hittite capital Hattusa or whether they simply moved into the vacuum left by the collapse of Hittite hegemony.

The Phrygian language /ˈfrɪdʒiən/ was the language spoken by the Phrygians in Asia Minor during Classical Antiquity (ca. 8th century BCE to 5th century CE). Phrygian is considered by some linguists to have been closely related to Greek.[239][240] The similarity of some Phrygian words to Greek ones was observed by Plato in his Cratylus (410a). However, Eric P. Hamp suggests that Phrygian was related to Italo-Celtic in a hypothetical "Northwest Indo-European" group.[241]

According to Herodotus, the Phrygians were initially dwelling in the southern Balkans under the name of Bryges (Briges), changing it to Phruges after their final migration to Anatolia, via the Hellespont. Though the migration theory is still defended by many modern historians, most archaeologists have abandoned the migration hypothesis regarding the origin of the Phrygians due to a lack substantial archaeological evidence, with the migration theory resting only on the accounts of Herodotus and Xanthus.[242]

From tribal and village beginnings, the state of Phrygia arose in the eighth century BCE with its capital at Gordium. During this period, the Phrygians extended eastward and encroached upon the kingdom of Urartu, the descendants of the Hurrians, a former rival of the Hittites. Meanwhile, the Phrygian Kingdom was overwhelmed by Cimmerian invaders around 690 BCE, then briefly conquered by its neighbour Lydia, before it passed successively into the Persian Empire of Cyrus the Great and the empire of Alexander and his successors, was taken by the Attalids of Pergamon, and eventually became part of the Roman Empire. The last mention of the Phrygian language in literature dates to the fifth century CE and it was likely extinct by the seventh century.[243]

Indo-Iranian migrations

Indo-Iranian peoples are a grouping of ethnic groups consisting of the Indo-Aryan, Iranian, Dardic and Nuristani peoples; that is, speakers of Indo-Iranian languages, a major branch of the Indo-European language family.

The Proto-Indo-Iranians are commonly identified with the Sintashta culture and the subsequent Andronovo culture within the broader Andronovo horizon, and their homeland with an area of the Eurasian steppe that borders the Ural River on the west, the Tian Shan on the east.

The Indo-Iranians interacted with the Bactria-Margiana Culture, also called "Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex". Proto-Indo-Iranian arose due to this influence.[244] The Indo-Iranians also borrowed their distinctive religious beliefs and practices from this culture.[244]

The Indo-Iranian migrations took place in two waves.[245][246] The first wave consisted of the Indo-Aryan migration into the Levant, founding the Mittani kingdom, and a migration south-eastward of the Vedic people, over the Hindu Kush into northern India.[3] The Indo-Aryans split-off around 1800–1600 BCE from the Iranians,[37] where-after they were defeated and split into two groups by the Iranians,[247] who dominated the Central Eurasian steppe zone[248] and "chased [the Indo-Aryans] to the extremities of Central Eurasia".[248] One group were the Indo-Aryans who founded the Mitanni kingdom in northern Syria;[249] (c. 1500–1300 BCE) the other group were the Vedic people.[250] Christopher I. Beckwith suggests that the Wusun, an Indo-European Caucasian people of Inner Asia in antiquity, were also of Indo-Aryan origin.[251]

The second wave is interpreted as the Iranian wave,[252] and took place in the third stage of the Indo-European migrations[3] from 800 BCE onwards.

Sintashta-Petrovka and Andronovo culture

Sintashta-Petrovka culture

The Sintashta culture, also known as the Sintashta-Petrovka culture[253] or Sintashta-Arkaim culture,[254] is a Bronze Age archaeological culture of the northern Eurasian steppe on the borders of Eastern Europe and Central Asia, dated to the period 2100–1800 BCE.[255] It is probably the archaeological manifestation of the Indo-Iranian language group.[256]

The Sintashta culture emerged from the interaction of two antecedent cultures. Its immediate predecessor in the Ural-Tobol steppe was the Poltavka culture, an offshoot of the cattle-herding Yamnaya horizon that moved east into the region between 2800 and 2600 BCE. Several Sintashta towns were built over older Poltavka settlements or close to Poltavka cemeteries, and Poltavka motifs are common on Sintashta pottery. Sintashta material culture also shows the influence of the late Abashevo culture, a collection of Corded Ware settlements in the forest steppe zone north of the Sintashta region that were also predominantly pastoralist.[257] Allentoft et al. (2015) also found close autosomal genetic relationship between peoples of Corded Ware culture and Sintashta culture.[125]

The earliest known chariots have been found in Sintashta burials, and the culture is considered a strong candidate for the origin of the technology, which spread throughout the Old World and played an important role in ancient warfare.[258] Sintashta settlements are also remarkable for the intensity of copper mining and bronze metallurgy carried out there, which is unusual for a steppe culture.[259]

Because of the difficulty of identifying the remains of Sintashta sites beneath those of later settlements, the culture was only recently distinguished from the Andronovo culture.[254] It is now recognised as a separate entity forming part of the 'Andronovo horizon'.[253]

Andronovo culture

The Andronovo culture is a collection of similar local Bronze Age Indo-Iranian cultures that flourished c. 1800–900 BCE in western Siberia and the west Asiatic steppe.[260] It is probably better termed an archaeological complex or archaeological horizon. The name derives from the village of Andronovo (55°53′N 55°42′E / 55.883°N 55.700°E), where in 1914, several graves were discovered, with skeletons in crouched positions, buried with richly decorated pottery. The older Sintashta culture (2100–1800), formerly included within the Andronovo culture, is now considered separately, but regarded as its predecessor, and accepted as part of the wider Andronovo horizon. At least four sub-cultures of the Andronovo horizon have been distinguished, during which the culture expands towards the south and the east:

- Sintashta-Petrovka-Arkaim (Southern Urals, northern Kazakhstan, 2200–1600 BCE)

- the Sintashta fortification of ca. 1800 BCE in Chelyabinsk Oblast

- the Petrovka settlement fortified settlement in Kazakhstan

- the nearby Arkaim settlement dated to the 17th century

- Alakul (2100–1400 BCE) between Oxus and Jaxartes, Kyzylkum desert

- Alekseyevka (1300–1100 BCE "final Bronze") in eastern Kazakhstan, contacts with Namazga VI in Turkmenia

- Ingala Valley in the south of the Tyumen Oblast

- Fedorovo (1500–1300 BCE) in southern Siberia (earliest evidence of cremation and fire cult)[261]

The geographical extent of the culture is vast and difficult to delineate exactly. On its western fringes, it overlaps with the approximately contemporaneous, but distinct, Srubna culture in the Volga-Ural interfluvial. To the east, it reaches into the Minusinsk depression, with some sites as far west as the southern Ural Mountains,[262] overlapping with the area of the earlier Afanasevo culture.[263] Additional sites are scattered as far south as the Koppet Dag (Turkmenistan), the Pamir (Tajikistan) and the Tian Shan (Kyrgyzstan). The northern boundary vaguely corresponds to the beginning of the Taiga.[262] In the Volga basin, interaction with the Srubna culture was the most intense and prolonged, and Federovo style pottery is found as far west as Volgograd.

Most researchers associate the Andronovo horizon with early Indo-Iranian languages, though it may have overlapped the early Uralic-speaking area at its northern fringe.

Bactria-Margiana Culture