South Slavs

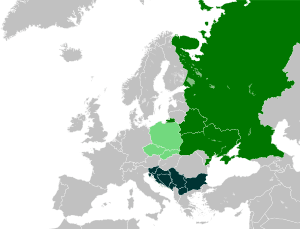

South Slavic countries West and East Slavic countries | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 30 million[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|

Majority: Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, Slovenia Minority: Albania, Greece, Kosovo (disputed status), Romania, Germany, Netherlands, Turkey, Italy, Poland, Hungary, Slovakia, Austria, Russia, Ukraine | |

| Languages | |

|

East South Slavic languages: Serbo-Croatian (Serbian, Croatian, Bosnian, Montenegrin) and Slovene | |

| Religion | |

| Orthodox Christianity (Bulgarians, Macedonians, Montenegrins and Serbs), Catholicism (Croats and Slovenes), Islam (Bosniaks, Pomaks and Torbeši) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Slavs |

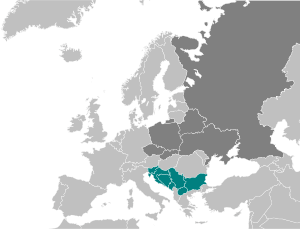

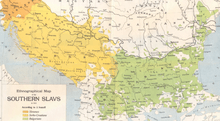

The South Slavs are a subgroup of Slavic peoples who speak the South Slavic languages. They inhabit a contiguous region in the Balkan Peninsula and the eastern Alps, and in the modern era are geographically separated from the body of West Slavic and East Slavic people by the Romanians, Hungarians, and Austrians in between (largely due to the border changes after World War I). The South Slavs today include the nations of Bosniaks, Bulgarians, Croats, Macedonians, Montenegrins, Serbs and Slovenes. They are the main population of the Eastern and Southeastern European countries of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia and Slovenia.

In the 20th century, the country of Yugoslavia (lit. "South Slavia") united the regions inhabited by South Slavic nations – with the key exception of Bulgaria – into a single state. The concept of Yugoslavia, a single state for all South Slavic peoples, emerged in the late 17th century and gained prominence through the 19th century Illyrian movement. The Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, renamed to the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1929, was proclaimed on 1 December 1918, following the unification of the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs with the kingdoms of Serbia and Montenegro.

Terminology

The South Slavs are known in Serbian, Macedonian and Montenegrin as Južni Sloveni (Cyrillic: Јужни Словени); in Bulgarian as Yuzhni Slavyani (Cyrillic: Южни славяни); in Croatian and Bosnian as Južni Slaveni; in Slovene as Južni Slovani. The Slavic root *jugъ means "south". The Slavic ethnonym itself was used by 6th-century writers to describe the southern group of Early Slavs (the Sclaveni); West Slavs were called Veneti and East Slavs Antes.[2] The South Slavs are also called "Balkan Slavs",[3] although this term does not encompass the Slovenes.

Another name popular in the Early modern period was "Illyrians", the name of a pre-Slavic Balkan people, a name first adopted by Dalmatian intellectuals in the late 15th century to refer to South Slavic lands and population.[4] It was then used by the Habsburg Monarchy, France, and notably adopted by the 19th-century Croatian nationalist and Pan-Slavist Illyrian movement.[5] Eventually, the idea of Yugoslavism appeared, aimed at uniting all South Slav-populated territories into a common state. From this idea emerged Yugoslavia, which however did not include Bulgaria.

History

Early South Slavs

The Proto-Slavic homeland is the area of Slavic settlement in Central and Eastern Europe during the first millennium AD, with its precise location debated by archaeologists, ethnographers and historians.[6] None of the proposed homelands reaches the Volga River in the east, over the Dinaric Alps in the southwest or the Balkan Mountains in the south, or past Bohemia in the west.[7] Traditionally, scholars put it in the marshes of Ukraine, alternatively between the Bug and the Dnieper,[8] however, according to F. Curta, the homeland of the southern Slavs mentioned by 6th-century writers was just north of the Lower Danube.[9] Little is known about the Slavs before the 5th century, when they began spreading in all directions.

Jordanes, Procopius and other late Roman authors provide the probable earliest references to southern Slavs in the second half of the 6th century.[10] Procopius described the Sclaveni and Antes as two barbarian peoples with the same institutions and customs since ancient times, not ruled by a single leader but living under democracy,[11] while Pseudo-Maurice called them a numerous people, undisciplined, unorganized and leaderless, who did not allow enslavement and conquest, and resistant to hardship, bearing all weathers.[12] They were portrayed by Procopius as unusually tall and strong, of dark skin and "reddish" hair (neither blond nor black), leading a primitive life and living in scattered huts, often changing their residence.[13] Procopius said they were henotheistic, believing in the god of lightning (Perun), the ruler of all, to whom they sacrificed cattle.[13] They went into battle on foot, charging straight at their enemy, armed with spears and small shields, but they did not wear armour.[13]

Slavs invaded and settled the Balkans in the 6th and 7th centuries.[14] Up until the late 560s their activity was raiding, crossing from the Danube, though with limited Slavic settlement mainly through Byzantine foederati colonies.[15] The Danube and Sava frontier was overwhelmed by large-scale Slavic settlement in the late 6th and early 7th century.[16] What is today central Serbia was an important geo-strategical province, through which the Via Militaris crossed.[17] This area was frequently intruded by barbarians in the 5th and 6th centuries.[17] From the Danube, the Slavs commenced raiding the Byzantine Empire from the 520s, on an annual basis, spreading destruction, taking loot and herds of cattle, seizing prisoners and taking fortresses. Often, the Byzantine Empire was stretched defending its rich Asian provinces from Arabs, Persians and others. This meant that even numerically small, disorganised early Slavic raids were capable of causing much disruption, but could not capture the larger, fortified cities.[15] The first Slavic raid south of the Danube was recorded by Procopius, who mentions an attack of the Antes, "who dwell close to the Sclaveni", probably in 518.[18] Sclaveni are first mentioned in the context of the military policy on the Danube frontier of Byzantine Emperor Justinian I (r. 527–565).[19] Throughout the century, Slavs raided and plundered deep into the Balkans, from Dalmatia to Greece and Thrace, and were also at times recruited as mercenaries, fighting the Ostrogoths.[20] Justinian seems to have used divide and conquer and the Sclaveni and Antes are mentioned as fighting each other.[21] The Antes are last mentioned as anti-Byzantine belligerents in 545, and the Sclaveni continued to raid the Balkans.[22] In 558 the Avars arrived at the Black Sea steppe, and defeated the Antes between the Dnieper and Dniester.[23] The Avars subsequently allied themselves with the Sclaveni,[24] although there was an episode in which the Sclaveni Daurentius (fl. 577–579), the first Slavic chieftain recorded by name, dismissed Avar suzerainty and retorted that "Others do not conquer our land, we conquer theirs [...] so it shall always be for us", and had the Avar envoys slain.[25] By the 580s, as the Slav communities on the Danube became larger and more organized, and as the Avars exerted their influence, raids became larger and resulted in permanent settlement. Most scholars consider the period of 581-584 as the beginning of large scale Slavic settlement in the Balkans.[26] F. Curta points out that evidence of substantial Slavic presence does not appear before the 7th century and remains qualitatively different from the "Slavic culture" found north of the Danube.[27] Byzantine re-assertion of the Danube defence in the mid-6th century and thereby lesser pillage yield (economic isolation) amidst external threats (Avars and Byzantines) resulted in political and military mobilisation and the itinerant form of agriculture (lacking crop rotation) may have encouraged micro-regional mobility. 7th-century archaeological sites shows earlier hamlet collections evolving into larger communities with differentiated designated areas (for public feasts, craftmanship, etc.).[28] It has been suggested that the Sclaveni were the ancestors of the Serbo-Croatian group while the Antes were that of the Bulgarian Slavs.[29] The diminished pre-Slavic inhabitants (including also Romanized native peoples[a]) fled Barbarian invasions and sought refuge inside fortified cities and islands, whilst others fled to remote mountains and forests and adopted a transhumant lifestyle.[30] The Romance-speakers within the fortified Dalmatian city-states managed to retain their culture and language for a long time.[31] The numerous Slavs mixed with and assimilated the descendants of the indigenous population.[32]

Subsequent information about Slavs' interaction with the Greeks and early Slavic states comes from the 10th-century De Administrando Imperio (DAI) by Emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus, the 7th-century compilations of Miracles of Saint Demetrius (MSD) and History by Theophylact Simocatta. DAI mentions the beginnings of the Croatian, Serbian and Bulgarian states, from the early 7th to the mid-10th century. MSD and Theophylact Simocatta mention the Slavic tribes in Thessaly and Macedonia at the beginning of the 7th century. The 9th-century Royal Frankish Annals (RFA) also mention Slavic tribes in contact with the Franks.

Middle Ages

By 700 AD, Slavs had settled in most of the Central and Southeast Europe, from Austria even down to the Peloponnese of Greece, and from the Adriatic to the Black Sea, with the exception of the coastal areas and certain mountainous regions of the Greek peninsula.[33] The Avars, who arrived in Europe in the late 550s and had a great impact in the Balkans, had from their base in the Carpathian plain, west of main Slavic settlements, asserted control over Slavic tribes with whom they besieged Roman cities. Their influence in the Balkans however diminished by the early 7th century and they were finally defeated and disappeared as a power at the turn of the 9th century.[34] The scattered Slavs in Greece, the Sklavinia, were Hellenized.[35] Romance-speakers lived within the fortified Dalmatian city-states.[31] Traditional historiography, based on DAI, holds that the migration of Serbs and Croats to the Balkans was part of a second Slavic wave, placed during Heraclius' reign.[36] These two peoples were said to have been invited into the Empire to protect it from the Avars.

Inhabiting the territory between the Franks in the north and Byzantium in the south, the Slavs were exposed to competing influences.[37] In 863 the Christianized Great Moravia sent for the two Byzantine monks Cyril and Methodius from Thessaloniki on missionary work. They created a Slavic written language, Old Church Slavonic, which they used to translate Biblical works. At the time, the West and South Slavs still spoke a similar language. The script used, Glagolithic, was capable of representing all Slavic sounds, however, it was replaced in the Balkans and Russia by Cyrillic in the 11th century.[38] Glagolithic survived into the 16th century in Croatia, used by Benedictines and Franciscans, but lost importance during the Counter-Reformation when Latin replaced it on the Dalmatian coast.[39] Cyril and Methodius' disciples found refuge in Bulgaria, where the non-Slavic idiom of the Bulgars would become extinct, and the Old Church Slavonic became the ecclesiastical language of all Orthodox Slavs.[39] The earliest Slavic literary works were composed in Macedonia, Duklja and Dalmatia. The religious works were almost exclusively translations, from Latin (Croatia, Slovenia) and especially Greek (Bulgaria, Serbia).[39] In the 10th and 11th centuries the Church Slavonic separated into regional idioms– Slovenian, Croatian, Serbian and Bulgarian.[39] Under the Bulgarian state, the religious centre of Ohrid and political centre of Plovdiv were important points of literary production.[40] The Bogomil sect, derived from Manichaeism, was deemed heretical, but managed to spread from Bulgaria to Bosnia (where it gained a foothold).[41]

Carinthia came under Germanic rule in the 10th century and came permanently under Western (Roman) Christian sphere of influence.[42] What is today Croatia came under Eastern Roman (Byzantine) rule after the Barbarian age, and while most of the territory was Slavicized, a handful of fortified towns, with mixed population, remained under Byzantine authority and continued to use Latin.[42] Dalmatia, now applied to the narrow strip with Byzantine towns, came under the Patriarchate of Constantinople, while the Croatian state remained pagan until Christianization during the reign of Charlemagne, after which religious allegiance was to Rome.[42] Croats threw off Frankish rule in the 11th century, and took over the Byzantine Dalmatian towns, after which Hungarian conquest led to Hungarian suzerainty, although retaining an army and institutions.[43] Croatia lost much of Dalmatia to the Republic of Venice which held it until the 18th century.[44] Hungary governed Croatia through a duke, and the coastal towns through a ban.[44] A feudal class emerged in the Croatian hinterland in the late 13th century, among whom were the Kurjaković, Kačić and most notably the Šubić.[45] Dalmatian fortified towns meanwhile maintained autonomy, with a Roman patrician class and Slavic lower class, first under Hungary and then Venice after centuries of struggle.[46]

Ibn al-Faqih described two kinds of South Slavic people, the first of swarthy complexion and dark hair, living near the Adriatic coast, and the other as light, living in the hinterland.

Early modern period

After Ottoman expansion on Byzantine territories in the east in the first half of the 14th century, Bulgaria and the crumbling Serbian Empire stood next. In 1371, the Ottomans defeated a large Serbian army at the Battle of Maritsa, and in 1389 defeated the Serbian army at the Battle of Kosovo. By now, Serbian and Bulgarian rulers became Ottoman vassals, the southern Serbian provinces and Bulgaria holding out until annexation in the 1390s. The Ottomans conquered Constantinople (1453), Greece (1453–60), Serbian Despotate (1459) and Bosnia (1463). Much of the Balkans was under Ottoman rule throughout the Early modern period. Ottoman rule lasted from the 14th century up until the early 20th in some territories. Ottoman society was multi-ethnic and multi-religious, and confessional groups were divided according to the Millet system, in which Orthodox Christians (Greeks, Bulgarians, Serbs, etc.) constituted the Rum Millet. In Islamic jurisprudence, the Christians had Dhimmi status, which included certain taxes and lesser rights. Islamization led to the forming of Slavic Muslims, that survive until today, in Bosnia, south Serbia, Macedonia and Bulgaria.

In the 16th century, the Habsburg Monarchy controlled what is today Slovenia, Croatia and northern Serbia. The Kingdom of Croatia, which included smaller parts of what is today Croatia, was a crown land of the Habsburg emperor. The Early modern period saw large-scale migrations of Orthodox Slavs (mainly Serbs) to the north and west. The Military Frontier was set up as the cordon sanitaire against Ottoman incursions. There were several rebellions against Ottoman rule, but it was not until the 18th century that parts of the Balkans, namely Serbia, were liberated for a longer period. While Pan-Slavism has its origins in the 17th-century Slavic Catholic clergymen in the Republic of Venice and Republic of Ragusa, it crystallized only in the mid-19th century amidst rise of nationalism in the Ottoman and Habsburg empires.

Statistics

| Bosnia | Bulgaria | Croatia | Macedonia | Montenegro | Serbia | Slovenia | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flag | |||||||

| Coat of arms |  |

|

|

|

|

| |

| Capital | Sarajevo | Sofia | Zagreb | Skopje | Podgorica | Belgrade | Ljubljana |

| Independence | March 3, 1992 |

October 5, 1908 |

June 26, 1991 |

November 17, 1991 |

June 3, 2006 |

June 8, 2006 |

June 25, 1991 |

| Current President | Bakir Izetbegović | Rumen Radev | Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović | Gjorge Ivanov | Milo Đukanović | Aleksandar Vučić | Borut Pahor |

| Current Prime Minister | Denis Zvizdić | Boyko Borisov | Andrej Plenković | Zoran Zaev | Duško Marković | Ana Brnabić | Miro Cerar |

| Population (2016) | 3,515,982 | 7,153,784 | 4,190,669 | 2,071,278 | 622,218 | 7,076,372 | 2,064,188 |

| Area | 51,197 km² | 110,879 km² | 56,594 km² | 25,713 km² | 13,812 km² | 77,474 km² | 20,273 km² |

| Density | 69/km² | 65/km² | 74/km² | 81/km² | 45/km² | 91/km² | 102/km² |

| Water area % | 0.02% | 2.16% | 1.1% | 1.09% | 2.61% | 0.13% | 0.6% |

| GDP (nominal) total (2018) | $18.564 billion | $49.364 billion | $57.868 billion | $10.424 billion | $4.182 billion | $42.139 billion | $43.791 billion |

| GDP (PPP) per capita (2018) | $11,950 | $19,097 | $25,580 | $14,009 | $16,123 | $13,671 | $31,007 |

| Gini Index (2012[47]) | 33.8 | 36.0 | 32.0 | 43.2 | 33.2 | 29.7 | 25.6 |

| HDI (2017) | 0.750 (High) | 0.794 (High) | 0.827 (Very High) | 0.748 (High) | 0.807 (Very High) | 0.776 (High) | 0.890 (Very High) |

| Internet TLD | .ba | .bg | .hr | .mk | .me | .rs | .si |

| Calling code | +387 | +359 | +385 | +389 | +382 | +381 | +386 |

Current leaders

Peoples and countries

South Slavs are divided linguistically into eastern (Bulgarian, and Macedonian) and western (Slovenes, Croatian, Bosnian, Serbian, and Montenegrin), and religiously into Orthodox (Serbs, Bulgarians, Macedonians, Montenegrins), Catholic (Croats, Slovenes) and Muslim (Bosniaks and other minorities). There are an estimated 35 million South Slavs and their descendants living worldwide. Among South Slavic ethnic groups (that are also nations), are the Serbs, Bulgarians, Croats, Bosniaks, Slovenes, Macedonians and Montenegrins. Bosniaks, Serbs and Croats are the constituent nations of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Montenegro is historically regarded a Serb nation, while Macedonia likewise a Bulgarian. Among South Slavic minorities or self-identifications are the Yugoslavs (former Yugoslavia), Muslims (former Yugoslavia), Torbeshi (R. Macedonia), Pomaks (Bulgaria, Greece) and Gorani (Kosovo). The Catholic Bunjevci and Šokci concentrated in northern Serbia and eastern Croatia are divided between a Croat or own identity. There are also smaller communities of West and East Slavic peoples in northern Serbia.

- Countries

There are seven countries in which South Slavs are the main population:[48]

In addition, there are local South Slavic minorities in non-South Slavic neighbouring countries such as:

- Albania: (Bulgarians, Macedonians, Serbs, Montenegrins)

- Austria: (Croats, Slovenes)*

- Greece: (Slavic-speakers of Greek Macedonia, Pomaks)

- Hungary: (Bulgarians, Croats, Slovenes and Serbs)

- Italy: (Slovenes, Croats, Serbs)

- Kosovo: (Serbs, Bosniaks)

- Moldova: (Bulgarians)

- Romania: (Croats, Bulgarians, Serbs, Macedonians)

- Slovakia: (Serbs)

- Turkey: (Bulgarians, Bosniaks, Montenegrins, Macedonians, Pomaks)

- Ukraine: (Bulgarians)

Cities

Largest cities in South Slavic states estimates for 1 October 2015 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Country | Pop. | Rank | Country | Pop. | ||||

Belgrade  Sofia |

1 | Belgrade | Serbia | 1,233,796 | 11 | Niš | Serbia | 187,544 | .jpg) Zagreb Skopje |

| 2 | Sofia | Bulgaria | 1,231,981 | 12 | Podgorica | Montenegro | 185,937 | ||

| 3 | Zagreb | Croatia | 790,017 | 13 | Banja Luka | Bosnia | 185,042 | ||

| 4 | Skopje | Republic of Macedonia | 506,926 | 14 | Split, Croatia | Croatia | 178,102 | ||

| 5 | Sarajevo | Bosnia | 395,133 | 15 | Kragujevac | Serbia | 150,835 | ||

| 6 | Plovdiv | Bulgaria | 338,153 | 16 | Rousse | Bulgaria | 149,642 | ||

| 7 | Varna | Bulgaria | 334,870 | 17 | Stara Zagora | Bulgaria | 138,272 | ||

| 8 | Ljubljana | Slovenia | 277,554 | 18 | Rijeka | Croatia | 128,314 | ||

| 9 | Novi Sad | Serbia | 277,522 | 19 | Tuzla | Bosnia | 110,979 | ||

| 10 | Burgas | Bulgaria | 200,271 | 20 | Zenica | Bosnia | 110,663 | ||

Religion

The religious and cultural diversity of the region the South Slavs inhabit has had a considerable influence on their religion. Originally a polytheistic pagan people, the South Slavs have also preserved many of their ancient rituals and traditional folklore, often intermixing and combining it with the religion they later converted to.

Today, the majority of South Slavs are Orthodox Christians; most Bulgarians, Macedonians, Serbs and Montenegrins are Orthodox Christians. Most Slovenes and Croats are Roman Catholics. Bosniaks, other minor ethnic groups (Gorani, Muslims by nationality) and sub-groups (Torbesh and Pomaks) are Muslims. Some South Slavs are atheist, agnostic and/or non-religious.

Orthodoxy

|

Catholicism

|

Islam

|

Languages

The South Slavic languages, one of three branches of the Slavic languages family (the other being West Slavic and East Slavic), form a dialect continuum. It comprises, from west to east, the official languages of Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, Serbia, Macedonia, and Bulgaria. The South Slavic languages are geographically divided from the rest of the Slavic languages by Germanic (Austria), Hungarian and Romanian.

South Slavic standard languages are:

|

West: |

East:

|

The Serbo-Croatian varieties have strong structural unity, and are regarded by most linguists as constituting one language.[50] Today, language secessionism has led to several standards: Serbian, Croatian, Bosnian and Montenegrin, although the latter has historically and traditionally been called Serbian and is still undergoing standardization. Bosnian was officially established in 1996. These Serbo-Croatian standards are all based on the Shtokavian dialect group. Other dialect groups, which have lower intelligibility with Shtokavian, are Chakavian in Dalmatia and Kajkavian in Croatia proper. The dominance of Shtokavian in the Western Balkans is due to historical westward migration during the Ottoman period. Slovene is grouped into South Slavic, but has many features shared with West Slavic languages. The Prekmurje Slovene and Kajkavian are especially close, and there is no clear delineation between them. In southeastern Serbia, dialects enter a transitional zone with Bulgarian and Macedonian, with features of both groups, and is commonly called Torlakian.

The East South Slavic languages are Bulgarian and Macedonian. Bulgarian has retained more archaic Slavic features in relation to the other languages. Bulgarian has two main yat splits. Slavic Macedonian was codified in Communist Yugoslavia in 1945 and was historically classified as Bulgarian. The Macedonian dialects, divided into three main groups, are overall regarded transitional to Bulgarian and Serbo-Croatian. The westernmost Bulgarian dialects (called Shopi) share features with Serbo-Croatian. Furthermore, in Greece there is a notable Slavic-speaking population in Greek Macedonia and western Thrace.

Balkan Slavic form a "Balkan sprachbund" of areal features with other non-Slavic languages in the Balkans.

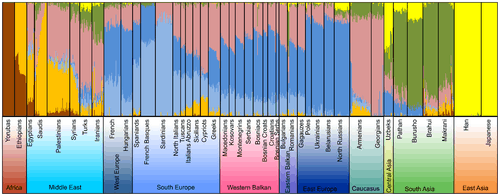

Genetics

The earliest genetic studies for population affinities were according to 'classical markers', i.e. protein and blood group polymorphisms, according to which Cavali-Sforza's team suggested several European cluster groups, "Germanic", "Scandinavian", "Celtic", south-western European and eastern European; the Yugoslavs (Bulgarians were not tested) did not group into any of the above but formed a group of their own, attributed to internal heterogeneity.

According to a 2006 Y-DNA study, most South Slavs clustered tightly together due to high frequency of I2a, while northern and western Croatians and Slovenians were instead clustered with neighbouring Central European (West Slavic and Hungarian) populations, due to higher frequency of R1a and R1b.[51] A 2008 study concluded that except for some isolated communities, Europeans are somewhat genetically homogeneous, and individual population groups are often closely related to their immediate neighbours (irrespective of language or ethnicity).[52][53] A study of 90 samples showed that Western Balkan populations had a genetic uniformity, intermediate between South Europe and Eastern Europe, in line with their geographic location.[54] Based on analysis of IBD sharing, Middle Eastern populations most likely did not contribute to genetics in Islamicized populations in the Western Balkans, as these share similar patterns with Christians.[54]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to South Slavs. |

Annotations

- ^ Prior to the advent of Roman rule, a number of native or autochthonous populations had lived in the Balkans since ancient times. South of the Jireček line were the Greeks. To the north, there were Illyrians, Thracians and Dacians. They were mainly tribalistic and generally lacked awareness of any ethno-political affiliation. Over the classical ages, they were at times invaded, conquered and influenced by Celts, Ancient Greeks and Ancient Rome. Roman influence, however, was initially limited to cities later concentrated along the Dalmatian coast, later spreading to a few scattered cities inside the Balkan interior particularly along the river Danube (Sirmium, Belgrade, Niš). Roman citizens from throughout the empire settled in these cities and in the adjacent countryside. Following the fall of Rome and numerous barbarian raids, the population in the Balkans dropped, as did commerce and general standards of living. Many people were killed, or taken prisoner by invaders. This demographic decline was particularly attributed to a drop in the number of indigenous peasants living in rural areas. They were the most vulnerable to raids and were also hardest hit by the financial crises that plagued the falling empire. However, the Balkans were not desolate; considerable numbers of indigenous people simply remained. Only certain areas tended to be affected by the raids (e.g. lands around major land routes, such as the Morava corridor).[55] In addition to the autochthons, there were remnants of previous invaders such as "Huns" and various Germanic peoples when the Slavs arrived. Sarmatian tribes (such as the Iazyges) are recorded to have still lived in the Banat region of the Danube.[56] The mixing of Slavs and other peoples is evident in genetic studies included in the article.

References

- ↑ South Slavs

- ↑ Kmietowicz 1976.

- ↑ Kmietowicz 1976, Vlasto 1970

- ↑ URI 2000, p. 104.

- ↑ Hupchick 2002, p. 199.

- ↑ Kobyliński 2005, pp. 525–526, Barford 2001, p. 37

- ↑ Kobyliński 2005, p. 526, Barford 2001, p. 332

- ↑ Fine 1991, p. 25.

- ↑ Curta 2006, p. 56.

- ↑ Curta 2001, pp. 71–73.

- ↑ James 2014, p. 95, Kobyliński 1995, p. 524

- ↑ Kobyliński 1995, pp. 524–525.

- 1 2 3 Kobyliński 1995, p. 524.

- ↑ Fine 1991, pp. 26–41.

- 1 2 Fine 1991, p. 29.

- ↑ Fine 1991, p. 33.

- 1 2 Živković 2002, p. 187.

- ↑ James 2014, p. 95, Curta 2001, p. 75

- ↑ Curta 2001, p. 76.

- ↑ Curta 2001, pp. 78–86.

- ↑ James 2014, p. 97.

- ↑ Byzantinoslavica. 61–62. Academia. 2003. pp. 78–79.

- ↑ Kobyliński 1995, p. 536.

- ↑ Kobyliński 1995, p. 537–539.

- ↑ Curta 2001, pp. 47, 91.

- ↑ Fine 1991, p. 31.

- ↑ Curta 2001, p. 308.

- ↑ Curta 2007, p. 61.

- ↑ Hupchick 2004, Fine 1991, p. 26

- ↑ Fine 1991, pp. 37.

- 1 2 Fine 1991, p. 35.

- ↑ Fine 1991, pp. 38, 41.

- ↑ Fine 1991, p. 36.

- ↑ Fine 1991, pp. 29–43.

- ↑ Fine 1991, p. 41.

- ↑ Curta 2001, p. 66.

- ↑ Portal 1969, p. 90.

- ↑ Portal 1969, pp. 90–92.

- 1 2 3 4 Portal 1969, p. 92.

- ↑ Portal 1969, p. 93.

- ↑ Portal 1969, pp. 93–95.

- 1 2 3 Portal 1969, p. 96.

- ↑ Portal 1969, p. 96–97.

- 1 2 Portal 1969, p. 97.

- ↑ Portal 1969, p. 97–98.

- ↑ Portal 1969, p. 98.

- ↑ GINI index

- ↑ "The World Factbook". cia.gov.

- ↑ Sarajevo, juni 2016. CENZUS OF POPULATION, HOUSEHOLDS AND DWELLINGS IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA, 2013 FINAL RESULTS (PDF). BHAS. Retrieved 30 June 2016.

- ↑ Comrie, Bernard & Corbett, Greville G., eds. (2002) [1st. Pub. 1993]. The Slavonic Languages. London & New York: Routledge. OCLC 49550401.

- ↑ Rębała et al. 2007.

- ↑ Novembre J, Johnson T, Bryc K; et al. (November 2008), "Genes mirror geography within Europe", Nature, 456 (7218): 98–101, Bibcode:2008Natur.456...98N, doi:10.1038/nature07331, PMC 2735096, PMID 18758442

- ↑ Lao O, Lu TT, Nothnagel M, et al. (August 2008), "Correlation between genetic and geographic structure in Europe", Curr. Biol., 18 (16): 1241–8, doi:10.1016/j.cub.2008.07.049, PMID 18691889, retrieved 2009-07-22

- 1 2 Kovacevic, Lejla; Tambets, Kristiina; Ilumäe, Anne-Mai; Kushniarevich, Alena; Yunusbayev, Bayazit; Solnik, Anu; Bego, Tamer; Primorac, Dragan; Skaro, Vedrana (2014-08-22). "Standing at the Gateway to Europe - The Genetic Structure of Western Balkan Populations Based on Autosomal and Haploid Markers". PLOS ONE. 9 (8): e105090. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9j5090K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0105090. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4141785. PMID 25148043.

- ↑ Fine 1991, pp. 9–12, 37.

- ↑ Fine 1991, p. 57.

Sources

- Primary sources

- Moravcsik, Gyula, ed. (1967) [1949]. Constantine Porphyrogenitus: De Administrando Imperio (2nd revised ed.). Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies.

- Scholz, Bernhard Walter, ed. (1970). Carolingian Chronicles: Royal Frankish Annals and Nithard's Histories. University of Michigan Press.

- Books

- Barford, Paul M. (2001). The Early Slavs: Culture and Society in Early Medieval Eastern Europe. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Castellan, Georges (1992). History of the Balkans: From Mohammed the Conqueror to Stalin. East European Monographs. ISBN 978-0-88033-222-4.

- Curta, Florin (2001). The Making of the Slavs: History and Archaeology of the Lower Danube Region, c. 500–700. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Curta, Florin (2006). Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500–1250. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Dvornik, Francis (1962). The Slavs in European History and Civilization. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

- Fine, John Van Antwerp Jr. (1991) [1983]. The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press.

- Fine, John Van Antwerp Jr. (1994) [1987]. The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press.

- Fine, John Van Antwerp Jr. (2005). When Ethnicity Did Not Matter in the Balkans: A Study of Identity in Pre-Nationalist Croatia, Dalmatia, and Slavonia in the Medieval and Early-Modern Periods. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press.

- Hupchick, Dennis P. (2004) [2002]. The Balkans: From Constantinople to Communism. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4039-6417-5.

- Janković, Đorđe (2004). "The Slavs in the 6th Century North Illyricum". Гласник Српског археолошког друштва. 20: 39–61.

- Jelavich, Barbara (1983a). History of the Balkans: Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries. 1. Cambridge University Press.

- Jelavich, Barbara (1983b). History of the Balkans: Twentieth Century. 2. Cambridge University Press.

- Kaimakamova, Miliana; Salamon, Maciej (2007). Byzantium, new peoples, new powers: the Byzantino-Slav contact zone, from the ninth to the fifteenth century. Towarzystwo Wydawnicze "Historia Iagellonica". ISBN 978-83-88737-83-1.

- Kobyliński, Zbigniew (1995). The Slavs. The New Cambridge Medieval History: Volume 1, C.500-c.700. Cambridge University Press. pp. 524–. ISBN 978-0-521-36291-7.

- Obolensky, Dimitri (1974) [1971]. The Byzantine Commonwealth: Eastern Europe, 500-1453. London: Cardinal.

- Ostrogorsky, George (1956). History of the Byzantine State. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Portal, Roger (1969) [1965]. The Slavs. Translated by Evans, Patrick (Translated from French ed.). Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

- Runciman, Steven (1930). A History of the First Bulgarian Empire. London: G. Bell & Sons.

- Samardžić, Radovan; Duškov, Milan, eds. (1993). Serbs in European Civilization. Belgrade: Nova, Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Institute for Balkan Studies.

- Singleton, Fred (1985). A Short History of the Yugoslav Peoples. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-27485-2.

- Stavrianos, Leften Stavros (2000). The Balkans Since 1453. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. ISBN 978-1-85065-551-0.

- Vlasto, Alexis P. (1970). The Entry of the Slavs into Christendom: An Introduction to the Medieval History of the Slavs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Živković, Tibor (2008). Forging unity: The South Slavs between East and West 550-1150. Belgrade: The Institute of History, Čigoja štampa.

- Journals

- Gitelman, Zvi; Hajda, Lubomyr A.; Himka, John-Paul; Solchanyk, Roman, eds. (2000). Cultures and Nations of Central and Eastern Europe: Essays in Honor of Roman Szporluk. Ukrainian Research Institute, Harvard University. ISBN 978-0-916458-93-5.

Further reading

- Jelavich, C., 1990. South Slav nationalisms--textbooks and Yugoslav Union before 1914. Ohio State Univ Pr.

- Petkov, K., 1997. Infidels, Turks, and women: the South Slavs in the German mind; ca. 1400-1600. Lang.

- Ferjančić, B., 2009. Vizantija i južni Sloveni. Ethos.

- Kovacevic, M.G.J., 1950. Pregled materijalne kulture Juznih Slovena.

- Filipovic, M.S., 1963. Forms and functions of ritual kinship among South Slavs. In V Congres international des sciences anthropologiques et ethnologiques (pp. 77-80).

- Šarić, L., 2004. Balkan identity: Changing self-images of the South Slavs. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural development, 25(5-6), pp.389-407.

- Ostrogorsky, G., 1963. Byzantium and the South Slavs. The Slavonic and East European Review, 42(98), pp.1-14.

.jpg)

.jpg)