Pannonian Avars

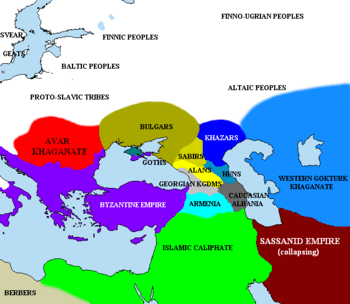

The Pannonian Avars (/ˈævɑːrz/; also known as the Obri in chronicles of Rus, the Abaroi or Varchonitai[2] (Varchonites) or Pseudo-Avars[3] in Byzantine sources) were an alliance of several groups of Eurasian nomads of unknown origins.[4][5][6][7][8][9]

They are probably best known for their invasions and destruction in the Avar–Byzantine wars from 568 to 626.

The name Pannonian Avars (after the area in which they eventually settled) is used to distinguish them from the Avars of the Caucasus, a separate people with whom the Pannonian Avars may or may not have been linked.

They established the Avar Khaganate, which spanned the Pannonian Basin and considerable areas of Central and Eastern Europe from the late 6th to the early 9th century.[10]

Although the name Avar first appeared in the mid-5th century, the Pannonian Avars entered the historical scene in the mid-6th century,[11] on the Pontic-Caspian steppe as a people who wished to escape the rule of the Göktürks.

Origins

Avars and Pseudo-Avars

The earliest clear reference to the Avar ethnonym comes from Priscus the Rhetor (died after 472 AD). Priscus recounts that, c. 463, the Šaragurs, Onogurs and Ogurs were attacked by the Sabirs, who had been attacked by the Avars. In turn, the Avars had been driven off by people fleeing "man-eating griffins" coming from "the ocean" (Priscus Fr 40).[12] Whilst Priscus' accounts provide some information about the ethno-political situation in the Don-Kuban-Volga region after the demise of the Huns, no unequivocal conclusions can be reached. Denis Sinor has argued that whoever the "Avars" referred to by Priscus were, they differed from the Avars who appear a century later, during the time of Justinian (who reigned from 527 to 565).[13]

The next author to discuss the Avars, Menander Protector, appeared during the 6th century, and wrote of Göktürk embassies to Constantinople in 565 and 568 AD. The Turks appeared angry at the Byzantines for having made an alliance with the Avars, whom the Turks saw as their subjects and slaves. Turxanthos, a Turk prince, calls the Avars "Varchonites" and "escaped slaves of the Turks", who numbered "about 20 thousand" (Menander Fr 43).[14]

Many more, but somewhat confusing, details come from Theophylact Simocatta, who wrote c. 629, but detailed the final two decades of the 6th century. In particular, he claims to quote a triumph letter from the Turk lord Tamgan:

For this very Chagan had in fact outfought the leader of the nation of the Abdeli (I mean indeed, of the Hephthalites, as they are called), conquered him, and assumed the rule of the nation.

Then he .. enslaved the Avar nation.

But let no one think that we are distorting the history of these times because he supposes that the Avars are those barbarians neighbouring on Europe and Pannonia, and that their arrival was prior to the times of the emperor Maurice. For it is by a misnomer that the barbarians on the Ister have assumed the appellation of Avars; the origin of their race will shortly be revealed.

So, when the Avars had been defeated (for we are returning to the account) some of them made their escape to those who inhabit Taugast. Taugast is a famous city, which is a total of one thousand five hundred miles distant from those who are called Turks,.. Others of the Avars, who declined to humbler fortune because of their defeat, came to those who are called Mucri; this nation is the closest neighbour to the men of Taugast;

Then the Chagan embarked on yet another enterprise, and subdued all the Ogur, which is one of the strongest tribes on account of its large population and its armed training for war. These make their habitations in the east, by the course of the river Til, which Turks are accustomed to call Melas. The earliest leaders of this nation were named Var and Chunni; from them some parts of those nations were also accorded their nomenclature, being called Var and Chunni.

Then, while the emperor Justinian was in possession of the royal power, a small section of these Var and Chunni fled from that ancestral tribe and settled in Europe. These named themselves Avars and glorified their leader with the appellation of Chagan. Let us declare, without departing in the least from the truth, how the means of changing their name came to them....

When the Barsils, Onogurs, Sabirs, and other Hun nations in addition to these, saw that a section of those who were still Var and Chunni had fled to their regions, they plunged into extreme panic, since they suspected that the settlers were Avars. For this reason they honoured the fugitives with splendid gifts and supposed that they received from them security in exchange.

Then, after the Var and Chunni saw the well-omened beginning to their flight, they appropriated the ambassadors' error and named themselves Avars: for among the Scythian nations that of the Avars is said to be the most adept tribe. In point of fact even up to our present times the Pseudo-Avars (for it is more correct to refer to them thus) are divided in their ancestry, some bearing the time-honoured name of Var while others are called Chunni....

According to the interpretation of Dobrovits and Nechaeva, the Turks insisted that the Avars were only pseudo-Avars, so as to boast that they were the only formidable power in the Eurasian steppe. The Gokturks claimed that the "real Avars" remained loyal subjects of the Turks, farther east.[13][15]

Furthermore, Dobrovits has questioned the authenticity of Theophylact's account. As such, they have argued that Theophylact borrowed information from Menander's accounts of Byzantine-Turk negotiations to meet political needs of his time – i.e. to castigate and deride the Avars during a time of strained political relations between the Byzantines and Avars (coinciding with Emperor Maurice's north Balkan campaigns). By calling the Avars "Turkish slaves" and "pseudo-Avars", Theophylact undermined their political legitimacy.[13]

Uar, Rouran and other Central Asian peoples

According to some scholars the Pannonian Avars originated from a confederation formed in the Aral Sea region, by the Uar, also known as the Var or Warr (who were probably a Uralic people) and the Xūn or Xionites (also known as the Chionitae, Chunni, Hunni, Yun and similar names);[16][17] the Xionites were most likely Iranian-speaking. A third tribe affiliated previously to the Uar and Xionites, the Hephthalites, had remained in Central and South Asia. In some transliterations, the term Var is rendered Hua, which is an alternate Chinese term for the Hephthalites. (While one of the cities most significant to the Hephthalites was Walwalij or Varvaliz, this may also be an Iranian term for "upper fortress".[18]) The Pannonian Avars were also known by names including Uarkhon or Varchonites – which may have been portmanteau words combining Var and Chunni.

The 18th-century historian Joseph de Guignes postulates a link between the Avars of European history with the proto-Mongolian Rouran (Ju-juan) of Inner Asia based on a coincidence between Tardan Khan's letter to Constantinople and events recorded in Chinese sources, notably the Wei-shi and Pei-shi.[18] Chinese sources state that Bumin Qaghan (T'u-men khan), founder of the Turkic Khaganate, defeated the Rouran, some of whom fled and joined the Western Wei. Later – according to another Chinese source – Muqan Qaghan (Mu-han khan), Bumin's successor, defeated the Hephthalites (Chinese name: I-ta) as well as the Turkic Tiele (Tieh-le). Superficially these victories over the Tiele, Rouran and Hephthalites echo a narrative in the Theophylact, boasting of Tardan's victories over the Hephthalites, Avars and Oghurs. However, the two series of events are not synonymous: the events of the letter took place during Tardan's rule, c. 580–599, whilst Chinese sources referring to the Turk defeat of the Rouran and other Central Asian peoples occurred 50 years earlier, at the founding of the Turk khanate by Bumen. It is for this reason that the linguist Janos Harmatta rejects the identification of the Avars with the Rouran. According to Edwin G. Pulleyblank the name Avar is the same as the prestigious name Wuhuan in the Chinese sources.[19]

Steppe empire dynamics and ethnogenesis

Contemporary scholars are less inclined to view the tribal groupings mentioned in historical texts as monolithic and long-lived 'nations', but were rather volatile and fluid political formations whose dynamic depended on the sedentary civilizations they bordered as well as internal power struggles within the barbarian lands.

In 2003, Walter Pohl summarized the formation of nomadic empires:[20]

1. Many steppe empires were founded by groups who had been defeated in previous power struggles but had fled from the dominion of the stronger group. The Avars were likely a losing faction previously subordinate to the (legitimate) Ashina clan in the Western Turkic Khaganate, and they fled west of the Dnieper.

2. These groups usually were of mixed origin, and each of its components was part of a previous group.

3. Crucial in the process was the elevation of a khagan, which signified a claim to independent power and an expansionist strategy. This group also needed a new name that would give all of its initial followers a sense of identity.

4. The name for a new group of steppe riders was often taken from a repertoire of prestigious names which did not necessarily denote any direct affiliation to or descent from groups of the same name; in the Early Middle Ages, Huns, Avars, Bulgars, and Ogurs, or names connected with -(o)gur (Kutrigurs, Utigurs, Onogurs, etc.), were most important. In the process of name-giving, both perceptions by outsiders and self-designation played a role. These names were also connected with prestigious traditions that directly expressed political pretensions and programmes, and had to be endorsed by success. In the world of the steppe, where agglomerations of groups were rather fluid, it was vital to know how to deal with a newly-emergent power. The symbolical hierarchy of prestige expressed through names provided some orientation for friend and foe alike.

Such views are mirrored by Csanád Bálint. "The ethnogenesis of early medieval peoples of steppe origin cannot be conceived in a single linear fashion due to their great and constant mobility", with no ethnogenetic "point zero", theoretical "proto-people" or proto-language.[21]

Moreover, Avar identity was strongly linked to Avar political institutions. Groups who rebelled or fled from the Avar realm could never be called "Avars", but were rather termed "Bulgars". Similarly, with the final demise of Avar power in the early 9th century, Avar identity disappeared almost instantaneously.[22]

Anthropological evidence

In contemporary art, Avars were sometimes depicted as mounted archers, riding backwards on their horses.[23]

According to mid-20th Century physical anthropologists such as Pál Lipták, human remains from the early Avar (7th century) period had mostly "Europoid" features, while grave goods indicated cultural links to the Eurasian steppe.[24]

Cemeteries dated to the late Avar period (8th century) included many human remains with physical features typical of East Asian people or Eurasians (i.e. people with both East Asian and European ancestry).[25] Remains with East Asian or Eurasian features were found in about one third of the Avar graves from the 8th Century.[26] According to Lipták, 79% of the population of the Danube-Tisza region during the Avar period showed Europoid characteristics.[24] (Lipták used racial terms later deprecated or regarded as obsolete, such as "Mongoloid" for North East Asian and "Turanid" for individuals of mixed ancestry.[27])

Several theories suggest that the ruling class of the Avars were of Tungusic origin or of partially Tungusic origin.[28]

Social and tribal structure

The Pannonian Basin was the centre of the Avar power-base. The Avars re-settled captives from the peripheries of their empire to more central regions. Avar material culture is found south to Macedonia. However, to the east of the Carpathians, there are next to no Avar archaeological finds, suggesting that they lived mainly in the western Balkans. Scholars propose that a highly structured and hierarchical Avar society existed, having complex interactions with other "barbarian" groups. The khagan was the paramount figure, surrounded by a minority of nomadic aristocracy.

A few exceptionally rich burials have been uncovered, confirming that power was limited to the khagan and a close-knit class of "elite warriors". In addition to hoards of gold coins that accompanied the burials, the men were often buried with symbols of rank, such as decorated belts, weapons, stirrups resembling those found in central Asia, as well as their horse. The Avar army was composed from numerous other groups: Slavic, Gepidic and Bulgar military units. There also appeared to have existed semi-independent "client" (predominantly Slavic) tribes which served strategic roles, such as engaging in diversionary attacks and guarding the Avars' western borders abutting the Frankish Empire.

Initially, the Avars and their subjects lived separately, except for Slavic and Germanic women who married Avar men. Eventually, the Germanic and Slavic peoples were included in the Avaric social order and culture, itself Persian-Byzantine in fashion.[29] Scholars have identified a fused, Avar-Slavic culture, characterized by ornaments such as half-moon-shaped earrings, Byzantine-styled buckles, beads, and bracelets with horn-shaped ends.[29] Paul Fouracre notes, "[T]here appears in the seventh century a mixed Slavic-Avar material culture, interpreted as peaceful and harmonious relationships between Avar warriors and Slavic peasants. It is thought possible that at least some of the leaders of the Slavic tribes could have become part of the Avar aristocracy".[30] Apart from the assimilated Gepids, a few graves of west Germanic (Carolingian) peoples have been found in the Avar lands. They perhaps served as mercenaries.[29]

Each year, the Huns [Avars] came to the Slavs, to spend the winter with them; then they took the wives and daughters of the Slavs and slept with them, and among the other mistreatments [already mentioned] the Slavs were also forced to pay levies to the Huns. But the sons of the Huns, who were [then] raised with the wives and daughters of these Wends [Slavs] could not finally endure this oppression anymore and refused obedience to the Huns and began, as already mentioned, a rebellion.

— Chronicle of Fredegar, Book IV, Section 48, written circa 642

Language

The language or languages spoken by the Avars are unknown.[4][6][7][8] Classical philologist Samuel Szadeczky-Kardoss states that most of the Avar words used in contemporaneous Latin or Greek texts, appear to have their origins in possibly Mongolian or Turkic languages.[31][32] Other theories propose a Tungusic origin.[33] According to Szadeczky-Kardoss, many of the titles and ranks used by the Pannonian Avars were also used by the Turks, Proto-Bulgars, Uighurs and/or Mongols, including khagan (or kagan), khan, kapkhan, tudun, tarkhan, and khatun.[32] There is also evidence, however, that ruling and subject clans spoke a variety of languages. Proposals by scholars include Caucasian,[6] Iranian,[34] Tungusic,[35][36][37] Hungarian[38] and Turkic.[2][39] A few scholars speculated that Proto-Slavic became the lingua franca of the Avar Khaganate.[40] Historian Gyula László has suggested that the late 9th century Pannonian Avars spoke a variety of Old Hungarian, thereby forming an Avar-Hungarian continuity with then newly arrived Hungarians.[41]

Gyula Lászlo's Avar-Hungarian continuity theory

Gyula László, a Hungarian archaeologist, suggests that late Avars, arriving to the qaganate in A.D 670 in great numbers, lived through the time between the destruction and plunder of the Avar state by the Franks during 791–795 and the arrival of the Magyars in 895. László points out that the settlements of the Hungarians (Magyars) did not replace but complement those of the Avars. Avars remained on the plough fields, good for agriculture, while Hungarians took the river banks and river flats, suitable for pastoring. He also notes that while the Hungarian graveyards consist of 40–50 graves on average, the Avars contain 600–1000. According to these findings the Avars not just survived the end of the Avar polity but lived in great masses and far outnumbered the Hungarian conquerors of Árpád. He also shows that Hungarians occupied only the centre of the Carpathian-basin, but Avars lived in a larger territory. Looking at those territories where only the Avars lived, one only finds Hungarian geographical names, not Slavic or Turkic as would be expected interspersed among them. This is further evidence for the Avar-Hungarian continuity. Names of the Hungarian tribes, chieftains and the words used for the leaders, etc., suggest that at least the leaders of the Hungarian conquerors were Turkic speaking. However, Hungarian is not a Turkic language, rather Finno-Ugric, and so they must have been assimilated by the Avars that outnumbered them and the genetics of today's modern Hungarians is no different than that of neighboring West Slavs as well as western Ukrainians. László's Avar-Hungarian continuity theory also states that the modern Hungarian language descends from that spoken by the Avars rather than the conquering Magyars.[42][43] László's research does suggest, at the very least, that it is likely that any remaining Avars in the Carpathian Basin who resisted Slavic assimilation were absorbed by the invading Magyars and lost their identity.

See also

Notes

Citations

- ↑ CNG Coins

- 1 2 Avars at the Encyclopedia of Ukraine

- ↑ According to Grousset, Empire of the Steppes, page 171,Theophylact Simocatta called them pseudo-Avars because he thought the true Avars were the Rouran.

- 1 2 "Avar". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved May 14, 2015.

Avar, one of a people of undetermined origin and language...

- ↑ Frassetto, Michael (1 January 2003). Encyclopedia of Barbarian Europe: Society in Transformation. ABC-CLIO. pp. 54–55. ISBN 978-1576072639. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

The exact origins of the Avars remain uncertain...

- 1 2 3 Waldman, Carl; Mason, Catherine (2006). Encyclopedia of European Peoples. Infobase Publishing. pp. 46–49. ISBN 978-1-4381-2918-1. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- 1 2 Beckwith 2009, pp. 390–391: "... the Avars certainly contained peoples belonging to several different ethnolinguistic groups, so that attempts to identify them with one or another specific eastern people are misguided."

- 1 2 Kyzlasov 1996, p. 322: "The Juan-Juan state was undoubtedly multi-ethnic, but there is no definite evidence as to their language... Some scholars link the Central Asian Juan-Juan with the Avars who came to Europe in the mid-sixth century. According to widespread but unproven and probably unjustified opinion, the Avars spoke a language of the Mongolic group."

- ↑ Pritsak (1983, p. 359)

- ↑ Walter Pohl, Die Awaren: ein Steppenvolk im Mitteleuropa, 567–822 n. Chr, C.H.Beck (2002), ISBN 978-3-406-48969-3, p. 26-29.

- ↑ Curta, Florin (2006). Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500–1250. Cambridge medieval textbooks. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-81539-0. Retrieved 2009-11-20.

- ↑ Maenchen-Helfen (1976, p. 436)

- 1 2 3 Dobrovits (2003)

- ↑ Whitby (1986, p. 226, footnote 48)

- ↑ Nechaeva (2011)

- ↑ Гулямов Я. Г., История орошения Хорезма с древнейших времен до наших дней, Ташкент, 1957.

- ↑ Муратов Б.А. Аланы, кавары и хиониты в этногенезе башкир//Урал-Алтай: через века в будущее: Материалы Всероссийской научной конференции. Уфа, 27 июня 2008.

- 1 2 Harmatta (2001)

- ↑ THE PEOPLES OF THE STEPPE FRONTIER IN EARLY CHINESE SOURCES, Edwin G. Pulleyblank, pages 35, 44[hrcak.srce.hr/file/161177]

- ↑ Pohl (2003, pp. 477–78)

- ↑ Balint (2010, p. 150)

- ↑ Pohl (1998)

- ↑ Archivum Eurasiae Medii Aevi, Vol. 4. Otto Harrassowitz, 1984

- 1 2 Erzsébet Fóthi, Anthropological conclusions of the study of Roman and Migration periods, Acta Biologica Szegediensis, Volume 44(1–4):87–94, 2000.

- ↑ "Acta archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae", Magyar Tudományos Akadémia, 1 Jan 1967, Page 86

- ↑ Russian Translation Series of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology ... – Page 21

- ↑ Lipták, Pál. Recherches anthropologiques sur les ossements avares des environs d'Üllö (1955) – In: Acta archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae, vol. 6 (1955), pp. 231–314

- ↑ Helimski, E (2004). "Die Sprache(n) der Awaren: Die mandschu-tungusische Alternative". Proceedings of the First International Conference on Manchu-Tungus Studies, Vol. II: 59–72.

- 1 2 3 History of Transylvania

- ↑ The New Cambridge Medieval History. Paul Fouracre

- ↑ http://www.uni-salzburg.at/fileadmin/oracle_file_imports/544328.PDF

- 1 2 Szadeczky-Kardoss 1990, p. 221.

- ↑ "Helimski: Early European Avars were (in part) Tungusic speakers". SARKOBOROS. 2014-09-08. Retrieved 2017-08-05.

- ↑ Curta, Florin (2004). "The Slavic lingua franca (Linguistic notes of an archaeologist turned historian)". East Central Europe/L'Europe du Centre-Est. 31: 125–148. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

By contrast, there is very little evidence that speakers of Slavic had any significant contact with Turkic. As a consequence, and since the latest stratum of loan words in Common Slavic is Iranian in origin, Johanna Nichols advanced the idea that the Avars spoke an Iranian, not a Turkic language.

- ↑ Futaky, I. (2001). Nyelvtörténeti vizsgálatok a Kárpát-medencei avar-magyar kapcsolatok kérdéséhez. Mongol és mandzsu-tunguz elemek nyelvünkben (in Hungarian). Budapest.

- ↑ Helimski, Eugene (2000). "Язык(и) аваров: тунгусо-маньчжурский аспект". Folia Orientalia 36 (Festschrift for St. Stachowski) (in Russian). pp. 135–148.

- ↑ Helimski, Eugene (2000). "On probable Tungus-Manchurian origin of the Buyla inscription from Nagy-Szentmiklós (preliminary communication)". Studia Etymologica Cracoviensia (5): 43–56.

- ↑ "Kettős honfoglalás". Wikipédia (in Hungarian). 2016-11-12.

- ↑ Róna-Tas, András (1999-01-01). Hungarians and Europe in the Early Middle Ages: An Introduction to Early Hungarian History. Central European University Press. p. 116. ISBN 9789639116481.

- ↑ Curta, Florin (2004). "The Slavic lingua franca (Linguistic Notes of an Archeologist Turned Historian)" (PDF). East Central Europe/L'Europe du Centre-Est. 31 (1): 132–148.

- ↑ "História 1982-01|Digitális Tankönyvtár". www.tankonyvtar.hu (in Hungarian). Retrieved 2016-11-30.

- ↑ László, Gyula (1978). A "kettős honfoglalás". Budapest, Hungary: Magvető Könyvkiadó.

- ↑ "Documentary with Gyula László". Duna Television.

Sources

- Beckwith, Christopher I. (16 March 2009). Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691135892. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- E. Breuer, "Chronological Studies to Early-Medieval Findings at the Danube Region. An Introduction to Byzantine Art at Barbaric Cemeteries." (Tettnang 2005).

- Curta, Florin (2006). Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500–1250. Cambridge Medieval Textbooks. ISBN 978-0-521-81539-0.

- Fine, John V. A., Jr (1991). The Early Medieval Balkans; A critical survey from the sixth to the late twelfth century. The University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-08149-3.

- Bruno Genito & Laszlo Madaras (eds.), (2005) "Archaeological Remains of a Steppe people in the Hungarian Great Plain: The Avarian Cemetery at Öcsöd 59. Final Reports. Naples". ISSN 1824-6117

- László Makkai & András Mócsy, editors, 2001. History of Transylvania, II.4, "The period of Avar rule"

- László Gyula: A "kettős honfoglalás" Magvető Könyvkiadó, 1978

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZbAG8vmUXdw Documentary with Gyula László in Hungarian, on state television channel Duna.

- Maenchen-Helfen, Otto (1976). The World of the Huns: Studies in Their History and Culture. University California Press. ISBN 9780520015968.

- Jarnut, Jorg; Pohl, Walter (2003). Regna and Gentes: The Relationship Between Late Antique and Early Medieval Peoples and Kingdoms in the Transformation of the Roman World. Brill. ISBN 90 04 12524 8.

- Pohl (1998). "Conceptions of Ethnicity in Early Medieval Studies". In Rosenwein. Debating the Middle Ages: Issues and Readings. Blackwell. ISBN 9781577180081.

- Kyzlasov, L. R. (1 January 1996). "Northern Nomads". In Litvinsky, B. A. History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The crossroads of civilizations, A.D. 250 to 750. UNESCO. pp. 315–325. ISBN 978-9231032110. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- Dobrovits, Mihaly (2003). ""They called themselves Avar" – Considering the pseudo-Avar question in the work of Theophylaktos". Transoxiana Webfestschrift Series I Webfestschrift Marshak 2003.

- Pritsak, Omeljan (1982). The Slavs and the Avars. Spoleto.

- Michael & Mary Whitby (1986). The History of Theophylact Simocatta: An English Translation with Introduction and Notes. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-822799-1.

- Ekaterina Nechaeva (2011). "The "Runaway" Avars and Late Antique Diplomacy". In Ralph W. Mathisen, Danuta Shanzer. Romans, Barbarians, and the Transformation of the Roman World: Cultural Interaction and the Creation of Identity in Late Antiquity. Ashgate.

- Janos Harmatta (2001). "The letter sent by the Turk Khagan to the Emperor Mauricius". Acta Archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae. 41: 109–118.

- Szadeczky-Kardoss, Samuel (1990). "The Avars". In Sinor, Denis. The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia. Vol. 1. Cambridge University Press. p. 221

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Eurasian Avars. |