Māori people

.jpg) A group of Māori performing a haka | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| approx. 885,000 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 723,400 (2016 estimate)[1] | |

| 142,107 (2016 census)[2] | |

| approx. 8,000 (2000)[3] | |

| 1,994 (2000)[4] | |

| 1,305 (2001)[5] | |

| Other regions | approx. 8,000[3] |

| Languages | |

| Māori, English | |

| Religion | |

|

Christianity Rātana Māori religions | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| other Polynesian peoples | |

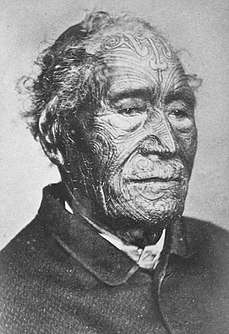

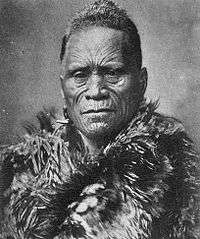

The Māori (/ˈmaʊri/; Māori pronunciation: [ˈmaːɔɾi] (![]()

The arrival of Europeans to New Zealand, starting in the 17th century, brought enormous changes to the Māori way of life. Māori people gradually adopted many aspects of Western society and culture. Initial relations between Māori and Europeans were largely amicable, and with the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840, the two cultures coexisted as part of a new British colony. Rising tensions over disputed land sales led to conflict in the 1860s. Social upheaval, decades of conflict and epidemics of introduced disease took a devastating toll on the Māori population, which fell dramatically. By the start of the 20th century, the Māori population had begun to recover, and efforts have been made to increase their standing in wider New Zealand society and achieve social justice. Traditional Māori culture has thereby enjoyed a significant revival, which was further bolstered by a Māori protest movement that emerged in the 1960s.

In the 2013 census, there were approximately 600,000 people in New Zealand identifying as Māori, making up roughly 15 per cent of the national population. They are the second-largest ethnic group in New Zealand, after European New Zealanders ("Pākehā"). In addition, more than 140,000 Māori live in Australia. The Māori language is spoken to some extent by about a fifth of all Māori, representing 3 per cent of the total population. Māori are active in all spheres of New Zealand culture and society, with independent representation in areas such as media, politics and sport.

Disproportionate numbers of Māori face significant economic and social obstacles, and generally have lower life expectancies and incomes compared with other New Zealand ethnic groups. They suffer higher levels of crime, health problems, and educational under-achievement. A number of socioeconomic initiatives have been instigated with the aim of "closing the gap" between Māori and other New Zealanders. Political and economic redress for historical grievances is also ongoing (see Treaty of Waitangi claims and settlements).

Etymology

| Look up Māori in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

In the Māori language, the word māori means "normal", "natural" or "ordinary". In legends and oral traditions, the word distinguished ordinary mortal human beings—tāngata māori—from deities and spirits (wairua).[9][i] Likewise, wai māori denotes "fresh water", as opposed to salt water. There are cognate words in most Polynesian languages,[10] all deriving from Proto-Polynesian *ma(a)qoli, which has the reconstructed meaning "true, real, genuine".[11][12]

The spelling of "Māori" with or without the macron is inconsistent in general-interest English-language media in New Zealand,[13] although some newspapers and websites have adopted the standard Māori-language spelling (i.e., with macrons).[14][15]

Naming and self-naming

Early visitors from Europe to New Zealand generally referred to the indigenous inhabitants as "New Zealanders" or as "natives".[16] The Māori used the term Māori to describe themselves in a pan-tribal sense.[ii] Māori people often use the term tangata whenua (literally, "people of the land") to identify in a way that expresses their relationship with a particular area of land; a tribe may be the tangata whenua in one area, but not in another.[17] The term can also refer to the Māori people as a whole in relation to New Zealand (Aotearoa) as a whole.

The Maori Purposes Act of 1947 required the use of the term "Māori" rather than "Native" in official usage. The Department of Native Affairs was renamed as the Department of Māori Affairs; since 1992 it has been known as Te Puni Kōkiri, or the Ministry for Māori Development.[18] Before 1974, the government required documented ancestry to determine the legal definition of "a Māori person". For example, bloodlines or percentage of Māori ancestry was used to determine whether a person should enroll on the general electoral roll or the separate Māori roll. In 1947, the authorities determined that a man who was five-eighths Māori had improperly voted in the general parliamentary electorate of Raglan.[19]

The Maori Affairs Amendment Act 1974 changed the definition, allowing individuals to self-identify as to their cultural identity. In matters involving financial benefits provided by the government to people of Māori ethnicity—scholarships, for example, or Waitangi Tribunal settlements—authorities generally require some documentation of ancestry or continuing cultural connection (such as acceptance by others as being of the people) but no minimum "blood" requirement exists as determined by the government.[20][iii]

History

Origins

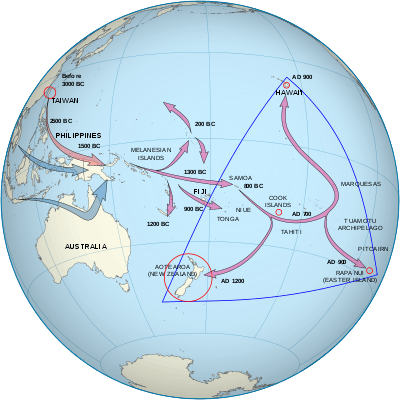

The most current reliable evidence strongly indicates that the initial settlement of New Zealand occurred around 1280 CE, at the end of the medieval warm period. Previous dating of some kiore (Polynesian rat) bones at 50–150 has now been shown to have been unreliable; new samples of bone (and now also of unequivocally rat-gnawed woody seed cases) match the 1280 date of the earliest archaeological sites and the beginning of sustained deforestation by humans.[21] Māori oral history describes the arrival of ancestors from Hawaiki (the mythical homeland in tropical Polynesia), in large ocean-going waka. Migration accounts vary among tribes (iwi), whose members may identify with several waka in their genealogies (whakapapa). In the last few decades, mitochondrial-DNA (mtDNA) research has allowed an estimate to be made of the number of women in the founding population—between 50 and 100.[22][23]

Evidence from archaeology, linguistics, and physical anthropology indicates that the first settlers came from east Polynesia and became the Māori. Language-evolution studies[24] and mtDNA evidence[25] suggest that most Pacific populations originated from Taiwanese aborigines around 5,200 years ago (suggesting prior migration from the Asian or Chinese mainland).[26] These ancestors moved down through Southeast Asia and Indonesia.[27]

Atholl Anderson concluded from analysis of mtDNA (female) and Y chromosome (male) that the ancestors of Polynesian women came from Taiwan while those of Polynesian men came from New Guinea. Subsequently it was found that 96 per cent of Polynesian mtDNA has an Asian origin, as do one-third of Polynesian Y chromosomes, with the remaining two-thirds being from New Guinea and nearby islands.[28] An Otago University study by Professor Matisoo-Smith shows that New Zealand was populated from southern Asia with the mtDNA mainly M branch with some N lineage and Denisovan DNA. Most Polynesians, Māori included, have mtDNA in the B4a1a branch, and the founding population is now known to have been in the hundreds—much larger than previously thought.[29][30]

Archaic period (1280–1500)

The earliest period of Māori settlement is known as the "Archaic", "Moahunter" or "Colonisation" period. The eastern Polynesian ancestors of the Māori arrived in a forested land with abundant birdlife, including several now extinct moa species weighing between 20 kilograms (44 lb) and 250 kg (550 lb) each. Other species, also now extinct, included a swan, a goose and the giant Haast's eagle, which preyed upon the moa. Marine mammals—seals in particular—thronged the coasts, with evidence of coastal colonies much further north than those which remain today.[31] Huge numbers of moa bones—estimated to be from between 29,000 and 90,000 birds—have been located at the mouth of the Waitaki River, between Timaru and Oamaru on the east coast of the South Island. Further south, at the mouth of the Shag River (Waihemo), evidence suggests that at least 6,000 moa were slaughtered by humans over a relatively short period of time.[32]

Archaeology has shown that the Otago region was the node of Māori cultural development during this time, and the majority of archaic settlements were on or within 10 km (6 mi) of the coast. It was common for people to establish small temporary camps far inland for seasonal hunting. Settlements ranged in size from 40 people (e.g., Palliser Bay in Wellington) to between 300 and 400 people, with 40 buildings (such as at the Shag River).

The best-known and most extensively studied Archaic site is at Wairau Bar in the South Island.[33][34] The site is similar to eastern Polynesian nucleated villages. Radiocarbon dating shows the site was occupied from about 1288 to 1300. Due to tectonic forces, some of the Wairau Bar site is now underwater. Work on the Wairau Bar skeletons in 2010 showed that life expectancy was very short, the oldest skeleton being 39 and most people dying in their 20s. Most of the adults showed signs of dietary or infection stress. Anemia and arthritis were common. Infections such as tuberculosis (TB) may have been present, as the symptoms were present in several skeletons. On average, the adults were taller than other South Pacific people, at 175 centimetres (5 ft 9 in) for males and 161 cm (5 ft 3 in) for females.

The Archaic period is remarkable for the lack of weapons and fortifications so typical of the later "Classic" Māori,[35] and for its distinctive "reel necklaces".[36] From this period onward, some 32 species of birds became extinct, either through over-predation by humans and the kiore and kurī (dog) they introduced;[37] repeated burning of the grassland that changed their habitat, or climate cooling, which appears to have occurred from about 1400–1450. The early Māori enjoyed a rich, varied diet of birds, fish, seals and shellfish. Moa were also an important source of meat. According to Professor Allan Cooper, the people slaughtered to extinction most of the various lost species within 100 years.[38]

Work by Helen Leach shows that Māori were using about 36 different food plants, although many required detoxification and long periods (12–24 hours) of cooking. D. Sutton's research on early Māori fertility found that first pregnancy occurred at about 20 years and the mean number of births was low, compared with other neolithic societies. The low number of births may have been due to the very low average life expectancy of 31–32 years.[38] Analysis of skeletons at Wairau Bar showed signs of a hard life, with many having had broken bones that had healed. This suggests that the people ate a balanced diet and enjoyed a supportive community that had the resources to support severely injured family members.

Classic period (1500–1642)

The cooling of the climate, confirmed by a detailed tree-ring study near Hokitika, shows a significant, sudden and long-lasting cooler period from 1500. This coincided with a series of massive earthquakes in the South Island Alpine fault, a major earthquake in 1460 in the Wellington area,[39] tsunamis that destroyed many coastal settlements, and the extinction of the moa and other food species. These were likely factors that led to sweeping changes in the Māori culture, which developed into the most well-known "Classic" period[40] that was in place at the time of European contact.

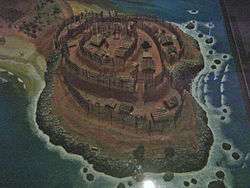

This period is characterised by finely made pounamu (greenstone) weapons and ornaments, elaborately carved canoes—a tradition that was later extended to and continued in elaborately carved meeting houses called wharenui[41]—and a fierce warrior culture. They developed hillforts known as pā, practiced cannibalism,[42][43][44] and built some of the largest war canoes ever.

Around the year 1500, a group of Māori migrated east to the Chatham Islands, where, by adapting to the local climate and the availability of resources, they developed into a people known as the Moriori,[45] related to but distinct from the Māori of mainland New Zealand. A notable feature of Moriori culture was an emphasis on pacifism. When a party of invading North Taranaki Māori arrived in 1835, few of the estimated Moriori population of 2,000 survived; they were killed outright and many were enslaved.[46]

The largest battle ever fought in New Zealand, the Battle of Hingakaka, occurred around 1780–90, south of Ōhaupō on a ridge near Lake Ngaroto. The battle was fought between about 7,000 warriors from a Taranaki-led force and a much smaller Waikato force under the leadership of Te Rauangaanga.

Early European contact (1642–1840)

European settlement of New Zealand occurred in relatively recent historical times. New Zealand historian Michael King in The Penguin History Of New Zealand describes the Māori as "the last major human community on earth untouched and unaffected by the wider world." Early European explorers, including Abel Tasman (who arrived in 1642) and Captain James Cook (who first visited in 1769), recorded their impressions of Māori. Initial contact between Māori and Europeans proved problematic and sometimes fatal, with several accounts of Europeans being cannibalised.[47]

.jpg)

From the 1780s, Māori encountered European and American sealers and whalers; some Māori crewed on the foreign ships, with many crewing on whaling and sealing ships that operated in New Zealand waters. Some of the South Island crews were almost totally Māori. Between 1800 and 1820, there were 65 sealing voyages and 106 whaling voyages to New Zealand, mainly from Britain and Australia.[48] A trickle of escaped convicts from Australia and deserters from visiting ships, as well as early Christian missionaries, also exposed the indigenous population to outside influences. In the Boyd Massacre in 1809, Māori took hostage and killed 66 members of the crew and passengers in apparent revenge for the captain's whipping the son of a Māori chief. Given accounts of cannibalism in this attack, shipping companies and missionaries kept their distance, significantly reducing their contact with the Māori for several years.[49]

The runaways were of various standing within Māori society, ranging from slaves to high-ranking advisors. Some runaways remained little more than prisoners, while others abandoned European culture and identified as Māori. These Europeans "gone native" became known as Pākehā Māori. Many Māori valued them as a means to acquire European knowledge and technology, particularly firearms. When Whiria (Pōmare II)[50] led a war-party against Tītore in 1838, he had 131 Europeans among his warriors.[51] Frederick Edward Maning, an early settler, wrote two lively accounts of life in these times, which have become classics of New Zealand literature: Old New Zealand and History of the War in the North of New Zealand against the Chief Heke. European settlement of New Zealand increased steadily. By 1839, estimates placed the number of Europeans living among the Māori as high as 2,000; two-thirds lived in the North Island, especially in the Northland Peninsula.[52]

Contact with Europeans led to a sharing of concepts. The Māori language was first written down by Thomas Kendall in 1815, in A korao no New Zealand; this was followed five years later by A Grammar and Vocabulary of the New Zealand Language, compiled by Professor Samuel Lee and aided by Kendall, Waikato Māori and the chief Hongi Hika, on a visit to England in 1820. Māori quickly adopted writing as a means of sharing ideas, and many of their oral stories and poems were converted to the written form.[53] Between February 1835 and January 1840, William Colenso printed 74,000 Māori-language booklets from his press at Pahia. In 1843, the government distributed free gazettes to Māori called Ko Te Karere O Nui Tireni.[54] These contained information about law and crimes, with explanations and remarks about European customs, and were "designed to pass on official information to Māori and to encourage the idea that Pākehā and Māori were contracted together under the Treaty of Waitangi".[55]

Between 1805 and 1840, the acquisition of muskets by tribes in close contact with European visitors upset the balance of power among Māori tribes. This led to a period of bloody intertribal warfare known as the Musket Wars, which resulted in the decimation of several tribes and the driving of others from their traditional territory.[56] It has been estimated that during this period the Māori population dropped from about 100,000 (in 1800) to between 50,000 and 80,000 by the wars' end in 1843. The 1850s were a decade of relative stability and economic growth for Māori.

The picture is confused by uncertainty over how or if Pākehā Māori were counted, and the severe dislocation of many of the less powerful iwi and hapū (subtribes) during the wars. The smashing of normal society by the four decades of wars and the driving of peaceful tribes from their productive turangawaewae, such as the Moriori in the Chatham Islands by invading forces from North Taranaki, had a catastrophic effect on these conquered tribes.

At the same time, the Māori suffered high mortality rates for new Eurasian infectious diseases, such as influenza, smallpox and measles, which killed an unknown number of Māori: estimates vary between ten and fifty percent.[57][58] The spread of epidemics resulted largely from the Māori lacking acquired immunity to the new diseases. A huge influx of European settlers in the 1870s increased contact among many of the indigenous people with the newcomers.

Te Rangi Hīroa documents an epidemic caused by a respiratory disease that Māori called rewharewha. It "decimated" populations in the early 19th century and "spread with extraordinary virulence throughout the North Island and even to the South... Measles, typhoid, scarlet fever, whooping cough and almost everything, except plague and sleeping sickness, have taken their toll of Māori dead."[59]

Economic changes also took a toll: migration of Māori workers into unhealthy swamplands to produce and export flax led to further mortality.[60]

Treaty with the British Crown (1840)

With increasing Christian missionary activity and growing European settlement in the 1830s, and with growing lawlessness in New Zealand, the British Crown acceded to repeated requests from missionaries and some chiefs (rangatira) to intervene. Some freewheeling escaped convicts and seamen, as well as gunrunners and Americans actively worked against the British government by spreading rumours amongst the Māori that the government would oppress and mistreat them. Tamati Waka Nene, a pro-government chief, was angry that the government had not taken active steps to stop gunrunners selling weapons to rebels in Hokianga. In addition, France appeared to be showing interest in acquiring New Zealand to add to its stake in Polynesia. British immigrants believed that the French Catholic missionaries were spreading anti-British feeling. All of the chiefs who spoke against the Treaty on 5 February 1840 were Catholic. Years after the treaty was signed, Bishop Pompallier admitted that all the Catholic chiefs and especially Rewa, had consulted him for advice.[61]

Ultimately, the British government sent Royal Navy Captain William Hobson with instructions to negotiate a treaty between the British Crown and the people of New Zealand. Soon after arrival in New Zealand in February 1840, Hobson negotiated a treaty with North Island chiefs, later to become known as the Treaty of Waitangi.[62] In the end, 500 tribal chiefs and a small number of Europeans signed the Treaty, while some chiefs — such as Te Wherowhero in Waikato[63] — refused to sign. The Treaty gave Māori the rights of British subjects and guaranteed Māori property rights and tribal autonomy, in return for accepting British sovereignty.[64]

Considerable dispute continues over aspects of the Treaty of Waitangi. The original treaty was written mainly by Busby and translated into Māori by Henry Williams, who was moderately proficient in Māori, and his son William, who was more skilled.[65] They were handicapped by their imperfect Māori and the lack of exactly similar words in Māori, as well as by deep differences among the peoples on concepts of property rights and sovereignty, for example.[66] At Waitangi the chiefs signed the Māori translation.

Land disputes and conflict

Despite conflicting interpretations of the provisions of the Treaty of Waitangi, relations between Māori and Europeans during the early colonial period were largely peaceful. Many Māori groups set up substantial businesses, supplying food and other products for domestic and overseas markets. Among the early European settlers who learnt the Māori language and recorded Māori mythology, George Grey, Governor of New Zealand from 1845–1855 and 1861–1868, stands out.

However, rising tensions over disputed land purchases and attempts by Māori in the Waikato to establish what some saw as a rival to the British system of royalty led to the New Zealand wars in the 1860s. These conflicts started when rebel Māori attacked isolated settlers in Taranaki but were fought mainly between Crown troops—from both Britain and new regiments raised in Australia, aided by settlers and some allied Māori (known as kupapa)—and numerous Māori groups opposed to the disputed land sales, including some Waikato Māori.

While these conflicts resulted in few Māori (compared to the earlier Musket wars) or European deaths, the colonial government confiscated tracts of tribal land as punishment for what were called rebellions. In some cases the government confiscated land from tribes that had taken no part in the war, although this was almost immediately returned. Some of the confiscated land was returned to both kupapa and "rebel" Māori. Several minor conflicts also arose after the wars, including the incident at Parihaka in 1881 and the Dog Tax War from 1897–98.

The Native Land Acts of 1862 and 1865 established the Native Land Court, which was intended to transfer Māori land from communal ownership into individual household title as a means to assimilation and to facilitate greater sales to European immigrants. Māori land under individual title became available to be sold to the colonial government or to settlers in private sales. Between 1840 and 1890, Māori sold 95 percent of their land (63,000,000 of 66,000,000 acres (270,000 km2) in 1890). In total 4 per cent of this was confiscated land, although about a quarter of this was returned. 300,000 acres was returned to Kupapa Māori mainly in the lower Waikato River Basin area. Individual Māori titleholders received considerable capital from these land sales, with some lower Waikato Chiefs being given 1000 pounds each. Disputes later arose over whether or not promised compensation in some sales was fully delivered. Some claim that later, the selling off of Māori land and the lack of appropriate skills hampered Māori participation in developing the New Zealand economy, eventually diminishing the capacity of many Māori to sustain themselves.

The Māori MP Henare Kaihau, from Waiuku, who was executive head of the King Movement, worked alongside King Mahuta to sell land to the government. At that time the king sold 185,000 acres per year. In 1910 the Māori Land Conference at Waihi discussed selling a further 600,000 acres. King Mahuta had been successful in getting restitution for some blocks of land previously confiscated, and these were returned to the King in his name. Henare Kaihau invested all the money- 50,000 pounds- in an Auckland land company which collapsed; all 50,000 pounds of the kingitanga money was lost.[67]

In 1884 King Tāwhiao withdrew money from the kingitanga bank, Te Peeke o Aotearoa[68][69] to travel to London to see Queen Victoria to try and persuade her to honour the Treaty between their peoples. He did not get past the Secretary of State for the Colonies, who said it was a New Zealand problem. Returning to New Zealand, the Premier Robert Stout insisted that all events happening before 1863 were the responsibility of the Imperial Government.[70]

By 1891 Māori comprised just 10 per cent of the population but still owned 17 per cent of the land, although much of it was of poor quality.[71]

Decline and revival

By the late 19th century a widespread belief existed amongst both Pākehā and Māori that the Māori population would cease to exist as a separate race or culture, and become assimilated into the European population.[72] In 1840, New Zealand had a Māori population of about 50,000 to 70,000 and only about 2,000 Europeans. By 1860 the Europeans had increased to 50,000. The Māori population had declined to 37,520 in the 1871 census, although Te Rangi Hīroa (Sir Peter Buck) believed this figure was too low.[73] The figure was 42,113 in the 1896 census, by which time Europeans numbered more than 700,000.[74] Professor Ian Pool noticed that as late as 1890, 40 per cent of all female Māori children who were born died before the age of one, a much higher rate than for males.[75]

The decline of the Māori population did not continue; it stabilized and began to recover. By 1936 the Māori figure was 82,326, although the sudden rise in the 1930s was probably due to the introduction of the family benefit − payable only when a birth was registered, according to Professor Pool. Despite a substantial level of intermarriage between the Māori and European populations, many ethnic Māori retained their cultural identity. A number of discourses developed as to the meaning of "Māori" and to who counted as Māori or not.

The parliament instituted four Māori seats in 1867, giving all Māori men universal suffrage,[76] 12 years ahead of their European New Zealand counterparts. Until the 1879 general elections, men had to satisfy property requirements of landowning or rental payments to qualify as voters.[77] New Zealand was thus the first neo-European nation in the world to give the vote to its indigenous people.[78] While the Māori seats encouraged Māori participation in politics, the relative size of the Māori population of the time vis à vis Pākehā would have warranted approximately 15 seats.

From the late 19th century, successful Māori politicians such as James Carroll, Āpirana Ngata, Te Rangi Hīroa and Maui Pomare, were influential in politics. At one point Carroll became Acting Prime Minister. The group, known as the Young Māori Party, cut across voting-blocs in Parliament and aimed to revitalise the Māori people after the devastation of the previous century. They believed the future path called for a degree of assimilation,[79] with Māori adopting European practices such as Western medicine and education, especially learning English.

Ngata acted as a major force behind the revival of arts such as kapa haka and carving. He also enacted a programme of land development, which helped many iwi retain and develop their land. Ngata became very close to Te Puea, the Waikato kingite leader, who was supported by the government in her attempt to improve living conditions for Waikato. Ngata transferred four blocks of land to Te Puea and her husband and arranged extensive government grants and loans. Ngata sacked the pakeha farm development officer and replaced him with Te Puea. He arranged for her to have a car to travel around the various farms. Te Puea's husband was also given a large farm at Tikitere near Rotorua. The public, media and parliament became alarmed at the flow of funds from government to Te Puea during the recession. A Royal Commission was held in 1934 that found Ngata guilty of maladministration and misappropriation of funds to the value of 500,000 pounds. Ngata was forced to resign.[80]

During the First World War, a Māori pioneer force was taken to Egypt but quickly was turned into a successful combat infantry battalion; in the last years of the war it was known as the Māori Battalion.[81] It mainly comprised Te Arawa, Te Aitanga-a-Māhaki, Te Aitanga-a-Hauiti, Ngāti Porou and Ngāti Kahungun and later many Cook Islanders; the Waikato and Taranaki tribes refused to enlist or be conscripted.[82]

Māori were badly hit by the 1918 influenza epidemic when the Māori battalion returned from the Western Front. The death rate from influenza for Māori was 4.5 times higher than for Pakeha. Many Māori, especially in the Waikato, were very reluctant to visit a doctor and went to a hospital only when the patient was nearly dead. To cope with isolation, Waikato Māori, under Te Puea's leadership, increasingly returned to the old Pai Mārire (Hau hau) cult of the 1860s.[83]

Until 1893, 53 years after the Treaty of Waitangi, Māori did not pay tax on land holdings. In 1893 a very light tax was payable only on leasehold land, and it was not till 1917 that Māori were required to pay a heavier tax equal to half that paid by other New Zealanders.[84]

During the Second World War, the government decided to exempt Māori from the conscription that applied to other citizens. The Māori volunteered in large numbers, forming the 28th or Māori Battalion,[85] which performed creditably, notably in Crete, North Africa and Italy.[86] Altogether 16,000 Māori took part in the war.[87] Māori, including Cook Islanders, made up 12 per cent of the total New Zealand force. 3,600 served in the Māori Battalion,[85] the remainder serving in artillery, pioneers, home guard, infantry, airforce, and navy.[87]

Many Māori migrated to larger rural towns and cities during the Depression and post-WWII periods in search of employment, leaving rural communities depleted and disconnecting many urban Māori from their traditional ways of life. Yet while standards of living improved among Māori during this time, they continued to lag behind Pākehā in areas such as health, income, skilled employment and access to higher levels of education. Māori leaders and government policymakers alike struggled to deal with social issues stemming from increased urban migration, including a shortage of housing and jobs, and a rise in urban crime, poverty and health problems.[88]

Recent history (1960s–present)

Since the 1960s, Māoridom has undergone a cultural revival[89] concurrent with activism for social justice and a protest movement.[90] Government recognition of the growing political power of Māori and political activism have led to limited redress for confiscation of land and for the violation of other property rights. In 1975 the Crown set up the Waitangi Tribunal,[91] a body with the powers of a Commission of Enquiry, to investigate and make recommendations on such issues, but it cannot make binding rulings; the Government need not accept the findings of the Waitangi Tribunal, and has rejected some of them.[92] Since 1976, people of Māori descent may choose to enroll on either the general or Māori roll, and vote in either the Māori only or general electorates, but not both.[93]

During the 1990s and 2000s, the government negotiated with Māori to provide redress for breaches by the Crown of the guarantees set out in the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840. By 2006 the government had provided over NZ$900 million in settlements, much of it in the form of land deals. The largest settlement, signed on 25 June 2008 with seven Māori iwi, transferred nine large tracts of forested land to Māori control.[94] As a result of the redress paid to many iwi, Māori now have significant interests in the fishing and forestry industries. There is a growing Māori leadership who are using the treaty settlements as an investment platform for economic development.[95]

Despite a growing acceptance of Māori culture in wider New Zealand society, the settlements have generated controversy on both sides. Some Māori have complained that the settlements occur at a level of between 1 and 2.5 cents on the dollar of the value of the confiscated lands; conversely, some non-Māori denounce the settlements and socioeconomic iniatives as amounting to race-based preferential treatment. Both of these sentiments were expressed during the New Zealand foreshore and seabed controversy in 2004.

Demographics

In the 2013 census, 598,605 people identified as being part of the Māori ethnic group, accounting for 14.9 per cent of the New Zealand population, while 668,724 people (17.5 per cent) claimed Māori descent.[96] Of those identifying as Māori, 278,199 people identified as of sole Māori ethnicity while 260,229 identified as of both European and Māori ethnicity, due to the high rate of intermarriage between the two cultures.[97] Under the Maori Affairs Amendment Act 1974, a Māori is defined as "a person of the Māori race of New Zealand; and includes any descendant of such a person".[98]

According to the 2013 census, the largest iwi by population is Ngāpuhi (125,601), followed by Ngāti Porou (71,049), Ngāi Tahu (54,819) and Waikato (40,083). However, over 110,000 people of Māori descent could not identify their iwi.[96] Outside of New Zealand, a large Māori population exists in Australia, estimated at 155,000 in 2011.[99] The Māori Party has suggested a special seat should be created in the New Zealand parliament representing Māori in Australia.[100] Smaller communities also exist in the United Kingdom (approx. 8,000), the United States (up to 3,500) and Canada (approx. 1,000).[3][101][5]

Culture

Traditional culture

The ancestors of the Māori arrived from eastern Polynesia during the 13th century, bringing with them Polynesian cultural customs and beliefs. Early European researchers, such as Julius von Haast, a geologist, incorrectly interpreted archaeological remains as belonging to a pre-Māori Paleolithic people; later researchers, notably Percy Smith, magnified such theories into an elaborate scenario with a series of sharply-defined cultural stages which had Māori arriving in a Great Fleet in 1350 and replacing the so-called "moa-hunter" culture with a "classical Māori" culture based on horticulture.[102] The development of Māori material culture has been similarly delineated by the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa into "cultural periods", from the earlier "Ngā Kakano" stage to the later "Te Tipunga" period, before the "Classic" period of Māori history.[36][iv][103]

However, the archaeological record indicates a gradual evolution of a neolithic culture that varied in pace and extent according to local resources and conditions.[104] In the course of a few centuries, the growing population led to competition for resources and an increase in warfare. The archaeological record reveals an increased frequency of fortified pā, although debate continues about the amount of conflict. Various systems arose which aimed to conserve resources; most of these, such as tapu and rāhui, used religious or supernatural threats to discourage people from taking species at particular seasons or from specified areas.

Warfare between tribes was common, generally over land conflicts or to restore mana. Fighting was carried out between hapū. Although not practised during times of peace, Māori would sometimes eat their conquered enemies.[105] As Māori continued in geographic isolation, performing arts such as the haka developed from their Polynesian roots, as did carving and weaving. Regional dialects arose, with differences in vocabulary and in the pronunciation of some words. In 1819 two young northern chiefs, Tuai and Titere,[106] who had learnt to speak and write English, went to London, where they met the language expert Samuel Lee. They stayed with a school teacher, Hall, who they told that even in Northern New Zealand there were "different languages and dialects".[107] The language retained enough similarities to other Eastern Polynesian languages, to the point where Tupaia, the Tahitian navigator on James Cook's first voyage in the region acted as an interpreter between Māori and the crew of the Endeavour.

Belief and religion

Traditional Māori beliefs have their origins in Polynesian culture. Many stories from Māori mythology are analogous with stories across the Pacific Ocean. Polynesian concepts such as tapu (sacred), noa (non-sacred), mana (authority/prestige) and wairua (spirit) governed everyday Māori living. These practices remained until the arrival of Europeans, when much of Māori religion and mythology was supplanted by Christianity. Today, Māori "tend to be followers of Presbyterianism, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormons), or Māori Christian groups such as Rātana and Ringatū",[108] but with Catholic, Anglican and Methodist groupings also prominent.[109][110] Islam is estimated as the fastest growing religion among Māori,[111] yet Māori Muslims constitute a very small proportion of Māori.

At the 2013 New Zealand census, 8.8 percent of Māori were affiliated with Māori Christian denominations and 39.6 percent with other Christian denominations; 46.3 percent of Māori claimed no religion. Proportions of Christian and irreligious Māori are comparable with European New Zealanders.[112]

Performing arts

Kapa haka (literally "haka team") is a traditional Māori performance art, encompassing many forms, that is still popular today. It includes haka (posture dance), poi (dance accompanied by song and rhythmic movements of the poi, a light ball on a string), waiata-ā-ringa (action songs) and waiata koroua (traditional chants). From the early 20th century kapa haka concert parties began touring overseas.

Since 1972 there has been a regular competition, the Te Matatini National Festival, organised by the Aotearoa Traditional Māori Performing Arts Society. Māori from different regions send representative groups to compete in the biennial competition. There are also kapa haka groups in schools, tertiary institutions and workplaces. It is also performed at tourist venues across the country.[113][114]

Literature and media

Like other cultures, oral folklore was used by Māori to preserve their stories and beliefs across many centuries. In the 19th century, European-style literacy was brought to the Māori, which led to Māori history documentation in books, novels and later television. Māori language use began to decline in the 20th century with English as the language through which Māori literature became widespread.

Notable Māori novelists include Patricia Grace, Witi Ihimaera and Alan Duff. Once Were Warriors, a 1994 film adapted from a 1990 novel of the same name by Alan Duff, brought the plight of some urban Māori to a wide audience. It was the highest-grossing film in New Zealand until 2006,[115][116] and received international acclaim, winning several international film prizes.[117] While some Māori feared that viewers would consider the violent male characters an accurate portrayal of Māori men, most critics praised it as exposing the raw side of domestic violence.[118] Some Māori opinion, particularly feminist, welcomed the debate on domestic violence that the film enabled.

Well-known Māori actors and actresses include Temuera Morrison, Cliff Curtis, Lawrence Makoare, Manu Bennett and Keisha Castle-Hughes. They are in films like Whale Rider, Star Wars: Episode III – Revenge of the Sith, The Matrix, King Kong, The River Queen, The Lord of The Rings, Rapa Nui, and others, and famous television series like Xena: Warrior Princess, Hercules: The Legendary Journeys, The Lost World and Spartacus: Blood and Sand. In most cases their roles in Hollywood productions have them portraying ethnic groups other than Māori.

Sport

Māori participate fully in New Zealand's sporting culture, and are well-represented in rugby union, rugby league and netball teams at all levels. The New Zealand national rugby union team performs a haka, a traditional Māori challenge, before international matches.[119] As well as participation in national sports teams, there are Māori rugby union, rugby league and cricket representative teams that play in international competitions.

At the 2016 Summer Olympics in Rio de Janeiro, 41 of the 199 competitors (20.5 percent) were of Māori descent in the New Zealand delegation, with the rugby sevens squads alone having 17 Māori competitors (out of 24). There were also three competitors of Māori descent in the Australian delegation.[120]

Ki-o-rahi and tapawai are two sports of Māori origin. Ki-o-rahi got an unexpected boost when McDonald's chose it to represent New Zealand.[121] Waka ama (outrigger canoeing) is also popular with Māori.

Language

From about 1890, Māori Members of Parliament realised the importance of English literacy to Māori and insisted that all Māori children be taught in English. Missionaries, who still ran many Māori schools, had been teaching exclusively in Māori but the Māori MPs insisted this should stop. However attendance at school for many Māori was intermittent.

The Māori language, also known as te reo Māori (pronounced [ˈmaːoɾi, te ˈɾeo ˈmaːoɾi]) or simply Te Reo ("the language"), has the status of an official language. Linguists classify it within the Eastern Polynesian languages as being closely related to Cook Islands Māori, Tuamotuan and Tahitian. Before European contact Māori did not have a written language and "important information such as whakapapa was memorised and passed down verbally through the generations".[122] Māori were familiar with the concept of maps and when interacting with missionaries in 1815 could draw accurate maps of their rohe (iwi boundaries), onto paper, that were the equal of European maps. Missionaries surmised that Māori had traditionally drawn maps on sand or other natural materials.[123]

In many areas of New Zealand, Māori lost its role as a living community language used by significant numbers of people in the post-war years. In tandem with calls for sovereignty and for the righting of social injustices from the 1970s onwards, New Zealand schools now teach Māori culture and language as an option, and pre-school kohanga reo ("language-nests") have started, which teach tamariki (young children) exclusively in Māori. These now extend right through secondary schools (kura tuarua). Most preschool centres teach basics such as colours, numerals and greetings in Māori songs and chants.[124]

Māori Television, a government-funded channel committed to broadcasting primarily in Te Reo, began in March 2004.[125] The 1996 census reported 160,000 Māori speakers.[126] At the time of the 2013 census 125,352 Māori (21.3 per cent) reported a conversational level of proficiency.[127]

Society

Historical development

Polynesian settlers in New Zealand developed a distinct society over several hundred years. Social groups were tribal, with no unified society or single Māori identity until after the arrival of Europeans. Nevertheless, common elements could be found in all Māori groups in pre-European New Zealand, including a shared Polynesian heritage, a common basic language, familial associations, traditions of warfare, and similar mythologies and religious beliefs.[128]

Most Māori lived in villages, which were inhabited by several whānau (extended families) who collectively formed a hapū (clan or subtribe). Members of a hapū cooperated with food production, gathering resources, raising families and defence. Māori society across New Zealand was broadly stratified into three classes of people: rangatira, chiefs and ruling families; tūtūā, commoners; and mōkai, slaves. Tohunga also held special standing in their communities as specialists of revered arts, skills and esoteric knowledge.[129][130]

Shared ancestry, intermarriage and trade strengthened relationships between different groups. Many hapū with mutually-recognised shared ancestry formed iwi, or tribes, which were the largest social unit in Māori society. Hapū and iwi often united for expeditions to gather food and resources, or in times of conflict. In contrast, warfare developed as an integral part of traditional life, as different groups competed for food and resources, settled personal disputes, and sought to increase their prestige and authority.[129]

The arrival of Europeans to New Zealand dates back to the 17th century, although it was not until the expeditions of James Cook over a hundred years later that any meaningful interactions occurred between Europeans and Māori. For Māori, the new arrivals brought opportunities for trade, which many groups embraced eagerly. Early European settlers introduced tools, weapons, clothing and foods to Māori across New Zealand, in exchange for resources, land and labour. Māori began selectively adopting elements of Western society during the 19th century, including European clothing and food, and later Western education, religion and architecture.[131]

But as the 19th century wore on, relations between European colonial settlers and different Māori groups became increasingly strained. Tensions led to conflict in the 1860s, and the confiscation of millions of acres of Māori land. Significant amounts of land were also purchased by the colonial government and later through the Native Land Court.

20th century

By the start of the 20th century, a greater awareness had emerged of a unified Māori identity, particularly in comparison to Pākehā, who now overwhelmingly outnumbered the Māori as a whole. Māori and Pākehā societies remained largely separate—socially, culturally, economically and geographically—for much of the 19th and early 20th centuries.[132] The key reason for this was that Māori remained almost exclusively a rural population, whereas increasingly the European population was urban especially after 1900. Nevertheless, Māori groups continued to engage with the government and in legal processes to increase their standing in (and ultimately further their incorporation into) wider New Zealand society.[133] The main point of contact with the government were the four Māori Members of Parliament.

Many Māori migrated to larger rural towns and cities during the Depression and post-WWII periods in search of employment, leaving rural communities depleted and disconnecting many urban Māori from their traditional social controls and tribal homelands. Yet while standards of living improved among Māori, they continued to lag behind Pākehā in areas such as health, income, skilled employment and access to higher levels of education. Māori leaders and government policymakers alike struggled to deal with social issues stemming from increased urban migration, including a shortage of housing and jobs, and a rise in urban crime, poverty and health problems.[88]

In regards to housing, a 1961 census revealed significant differences in the living conditions of Māori and Europeans. That year, out of all the (unshared) non-Māori private dwellings in New Zealand, 96.8 per cent had a bath or shower, 94.1 per cent a hot water service, 88.7 per cent a flush toilet, 81.6 per cent a refrigerator, and 78.6 per cent an electric washing machine. By contrast, for all (unshared) Māori private dwellings that same year, 76.8 per cent had a bath or shower, 68.9 per cent a hot water service, 55.8 per cent a refrigerator, 54.1 per cent a flush toilet, and 47 per cent an electric washing machine.[134]

While the arrival of Europeans had a profound impact on the Māori way of life, many aspects of traditional society have survived into the 21st century. Māori participate fully in all spheres of New Zealand culture and society, leading largely Western lifestyles while also maintaining their own cultural and social customs. The traditional social strata of rangatira, tūtūā and mōkai have all but disappeared from Māori society, while the roles of tohunga and kaumātua are still present. Traditional kinship ties are also actively maintained, and the whānau in particular remains an integral part of Māori life.[135]

Marae, hapū and iwi

Māori society at a local level is particularly visible at the marae. Formerly the central meeting spaces in traditional villages, marae today usually comprise a group of buildings around an open space, that frequently host events such as weddings, funerals, church services and other large gatherings, with traditional protocol and etiquette usually observed. They also serve as the base of one or sometimes several hapū.[136]

Most Māori affiliate with one or more iwi (and hapū), based on genealogical descent (whakapapa). Iwi vary in size, from a few hundred members to over 100,000 in the case of Ngāpuhi. Many people do not live in their traditional tribal regions as a result of urban migration.

Iwi are usually governed by rūnanga (governing councils or trust boards) which represent the iwi in consultations and negotiations with the New Zealand government. Rūnanga also manage tribal assets and spearhead health, education, economic and social initiatives to help iwi members.

Socioeconomic challenges

Māori on average have fewer assets than the rest of the population, and run greater risks of many negative economic and social outcomes. Over 50 per cent of Māori live in areas in the three highest deprivation deciles, compared with 24 per cent of the rest of the population.[137] Although Māori make up only 14 per cent of the population, they make up almost 50 per cent of the prison population.[138]

Māori have higher unemployment-rates than other cultures resident in New Zealand [139] Māori have higher numbers of suicides than non-Māori.[140] "Only 47 per cent of Māori school-leavers finish school with qualifications higher than NCEA Level One; compared to 74 per cent European; 87 per cent Asian."[141] Although New Zealand rates very well globally in the PISA rankings that compare national performance in reading, science and maths, "once you disaggregate the PISA scores, Pakeha students are second in the world and Maori are 34th."[142] Māori suffer more health problems, including higher levels of alcohol and drug abuse, smoking and obesity. Less frequent use of healthcare services mean that late diagnosis and treatment intervention lead to higher levels of morbidity and mortality in many manageable conditions, such as cervical cancer,[143] diabetes[144] per head of population than non-Māori.[145] Although Māori life expectancy rates have increased dramatically in the last 50 years, they still have considerably lower life-expectancies compared to New Zealanders of European ancestry: in 2004, Māori males lived 69.0 years vs. non-Māori males 77.2 years; Māori females 73.2 yrs vs. non-Māori females 81.9 years.[146] This gap had narrowed by 2013: 72.8 years for men and 76.5 years for women, compared to 80.2 years for non-Māori men and 83.7 years for non-Māori women.[147] Also, a recent study by the New Zealand Family Violence Clearinghouse showed that Māori women and children are more likely to experience domestic violence than any other ethnic group.[148]

Race relations

The status of Māori as the indigenous people of New Zealand is recognised in New Zealand law by the term tangata whenua (lit. "people of the land"), which identifies the traditional connection between Māori and a given area of land. Māori as a whole can be considered as tangata whenua of New Zealand entirely; individual iwi are recognised as tangata whenua for areas of New Zealand in which they are traditionally based, while hapū are tangata whenua within their marae. New Zealand law periodically requires consultation between the government and tangata whenua—for example, during major land development projects. This usually takes the form of negotiations between local or national government and the rūnanga of one or more relevant iwi, although the government generally decides which (if any) concerns are acted upon.

Māori issues are a prominent feature of race relations in New Zealand. Historically, many Pākehā viewed race relations in their country as being the "best in the world", a view that prevailed until Māori urban migration in the mid-20th century brought cultural and socioeconomic differences to wider attention.[149]

Māori protest movements grew significantly in the 1960s and 1970s seeking redress for past grievances, particularly in regard to land rights. Successive governments have responded by enacting affirmative action programmes, funding cultural rejuvenation initiatives and negotiating tribal settlements for past breaches of the Treaty of Waitangi.[150] Further efforts have focused on cultural preservation and reducing socioeconomic disparity.

Nevertheless, race relations remains a contentious issue in New Zealand society. Māori advocates continue to push for further redress claiming that their concerns are being marginalised or ignored. A 2007 Department of Corrections report found that Māori are disproportionately represented in the criminal justice system not only because they commit more crimes but also because they face prejudice at many levels: "a number of studies have shown evidence of greater likelihood, associated only with ethnicity, for Māori offenders to have police contact, be charged, lack legal representation, not be granted bail, plead guilty, be convicted, be sentenced to non-monetary penalties, and be denied release to Home Detention".[151] Conversely, critics denounce the scale of assistance given to Māori as amounting to preferential treatment for a select group of people based on race.[152] Both sentiments were highlighted during the foreshore and seabed controversy in 2004, in which the New Zealand government claimed sole ownership of the New Zealand foreshore and seabed, over the objections of Māori groups who were seeking customary title.[153]

Commerce

The New Zealand Law Commission has started a project to develop a legal framework for Māori who want to manage communal resources and responsibilities. The voluntary system proposes an alternative to existing companies, incorporations, and trusts in which tribes and hapū and other groupings can interact with the legal system. The foreshadowed legislation, under the proposed name of the "Waka Umanga (Māori Corporations) Act", would provide a model adaptable to suit the needs of individual iwi.[154][155] At the end of 2009, the proposed legislation was awaiting a second hearing.[156]

Wider commercial exposure has increased public awareness of the Māori culture, but has also resulted in several notable legal disputes. Between 1998 and 2006, Ngāti Toa attempted to trademark the haka "Ka Mate" to prevent its use by commercial organisations without their permission.[157] In 2001, Danish toymaker Lego faced legal action by several Māori tribal groups (fronted by lawyer Maui Solomon) and members of the on-line discussion forum Aotearoa Cafe for trademarking Māori words used in naming the Bionicle product range (see Bionicle Māori controversy).

Political representation

Māori have been involved in New Zealand politics since the Declaration of the Independence of New Zealand, before the Treaty of Waitangi was signed in 1840. Māori have had reserved seats in the New Zealand Parliament since 1868: presently, this accounts for seven of the 122 seats in New Zealand's unicameral parliament. The contesting of these seats was the first opportunity for many Māori to participate in New Zealand elections, although the elected Māori representatives initially struggled to assert significant influence. Māori received universal suffrage with other New Zealand citizens in 1893.

Being a traditionally tribal people, no one organisation ostensibly speaks for all Māori nationwide. The Māori King Movement originated in the 1860s as an attempt by several iwi to unify under one leader: in modern times, it serves a largely ceremonial role. Another attempt at political unity was the Kotahitanga Movement, which established a separate Māori Parliament that held annual sessions from 1892 until its last sitting in 1902.[159]

There are seven designated Māori seats in the New Zealand Parliament (and Māori can and do stand in and win general roll seats), and consideration of and consultation with Māori have become routine requirements for councils and government organisations.[93]

Debate occurs frequently as to the relevance and legitimacy of the Māori electoral roll and seats. The National Party announced in 2008 it would abolish the seats when all historic Treaty settlements have been resolved, which it aimed to complete by 2014.[160] However, after the election National reached an agreement with the Māori Party not to abolish the seats until Māori give their approval.[161]

Several Māori political parties have formed over the years to improve the position of Māori in New Zealand society. The present Māori Party, formed in 2004, secured 1.32 per cent of the party vote at the 2014 general election and held two seats in the 51st New Zealand Parliament, with two MPs serving as Ministers outside Cabinet. The party did not achieve any representatives in the 52nd New Zealand Parliament.[162]

Notes

- ^i : Māori has cognates in other Polynesian languages such as Hawaiian maoli, Tahitian mā'ohi, and Cook Islands Maori māori which all share similar meanings.

- ^ii : The orthographic conventions developed by the Māori Language Commission (Te Taura Whiri i te Reo Māori) recommend the use of the macron (ā ē ī ō ū) to denote long vowels. Contemporary English-language usage in New Zealand tends to avoid the anglicised plural form of the word Māori with an "s": The Māori language generally marks plurals by changing the article rather than the noun, for example: te waka (the canoe); ngā waka (the canoes).

- ^iii : In 2003, Christian Cullen became a member of the Māori rugby team despite having, according to his father, about 1/64 Māori ancestry.[163]

- ^iv : Although, as noted elsewhere in this article, evidence is increasingly pointing to 1280 as the earliest date of settlement.

References

- ↑ "Māori Population Estimates: At 30 June 2016 – tables". www.stats.govt.nz. Retrieved 2017-10-29.

- ↑ "2016 Census Community Profiles: Australia". www.censusdata.abs.gov.au. Retrieved 2017-10-28.

- 1 2 3 Walrond, Carl (4 March 2009). "Māori overseas". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 7 December 2010.

- 1 2 "Table 1. First, Second, and Total Responses to the Ancestry Question by Detailed Ancestry Code: 2000". census.gov. US Census Bureau.

- 1 2 Statistics Canada (2003).(232), Sex (3) and Single and Multiple Responses (3) for Population, for Canada, Provinces, Territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations, 2001 Census – 20% Sample Data. Ottawa: Statistics Canada, Cat. No. 97F0010XCB2001001.

- ↑ "Maori". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Howe (2003), p. 179

- ↑ "Rat remains help date New Zealand's colonisation". New Scientist. 4 June 2008. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- ↑ Atkinson, A. S. (1892)."What is a Tangata Maori?" Journal of the Polynesian Society, 1 (3), 133–136. Retrieved 18 December 2007.

- ↑ e.g. kanaka maoli, meaning native Hawaiian. (In the Hawaiian language, the Polynesian letter "T" regularly becomes a "K," and the Polynesian letter "R" regularly becomes an "L")

- ↑ "Entries for MAQOLI [PN] True, real, genuine: *ma(a)qoli". pollex.org.nz.

- ↑ Eastern Polynesian languages

- ↑ "Maori". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- ↑ "Why Stuff is introducing macrons for te reo Māori words". Stuff.co.nz. 11 September 2017. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- ↑ "Official language to receive our best efforts". Horowhenua Chronicle. NZME. 9 May 2018. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

From this week, the Horowhenua Chronicle and all websites and newspaper publications in the NZME group, take a big step toward giving the Māori language the recognition it deserves.

- ↑ "Native Land Act | New Zealand [1862]". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ↑ "tangata whenua". Māori Dictionary. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ↑ "Who We Are". Te Puni Kōkiri. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- ↑ Atkinson, Neill, (2003). Adventures in Democracy: A History of the Vote in New Zealand, Otago University Press

- ↑ McIntosh (2005), p. 45

- ↑ Lowe, David J. (2008). "Polynesian Settlement of New Zealand and the Impacts of Volcanism on Early Maori Society: An Update" (PDF). University of Waikato. Retrieved 29 April 2010.

- ↑ "Rethinking Polynesian Origins: Human Settlement of the Pacific", Michal Denny, and Lisa Matisoo-Smith

- ↑ "Maori Migration" Archived 30 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine., Bernard Carpinter, NZ Science Monthly

- ↑ "Language study links Maori to Taiwan". Stuff.co.nz. 24 January 2009. Retrieved 19 October 2011.

- ↑ (2005) "Mitochondrial DNA Provides a Link between Polynesians and Indigenous Taiwanese". PLoS Biology 3(8): e281. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0030281

- ↑ "Pacific People Spread From Taiwan, Language Evolution Study Shows". ScienceDaily. 27 January 2009. Retrieved 29 April 2010.

- ↑ "DNA questions Pacific origins". The New Zealand Herald. 19 July 2000. Retrieved 19 October 2011.

- ↑ Anderson, Atholl (2016). The First Migration: Māori Origins 3000BC- AD1450. Wellington: Bridget Williams Books. p. 20. ISBN 9780947492793.

- ↑ "The ancient origins of New Zealanders". Stuff (Fairfax). 15 January 2018.

- ↑ "Who were the first humans to reach New Zealand". Stuff (Fairfax). 22 January 2018.

- ↑ Irwin (2006), pp 10–18

- ↑ M King. Penguin History of NZ. Penguin, 2012

- ↑ "Maori Colonisation", Te Ara

- ↑ "Wairau Bar Excavation Study ", University of Otago

- ↑ "The Moa Hunters", 1966, An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand,

- 1 2 "Nga Kakano: 1100 – 1300", Te Papa

- ↑ "Early human impact", Te Ara

- 1 2 Houghton, Philip (1980). The First New Zealanders. Hodder & Stoughton.

- ↑ Maclean, Chris (3 March 2009). "Creation stories and landscape – Wellington region". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ↑ "Te Puawaitanga: 1500 – 1800", Te Papa

- ↑ Neich Roger, 2001. Carved Histories: Rotorua Ngati Tarawhai Woodcarving. Auckland: Auckland University Press, pp 48–49.

- ↑ Masters, Catherine (8 September 2007). "'Battle rage' fed Maori cannibalism". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 19 October 2011.

- ↑ HONGI HIKA (c. 1780–1828) Ngapuhi war chief, the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

- ↑ James Cowan, The New Zealand Wars: A History of the Maori Campaigns and the Pioneering Period: Volume II, 1922.

- ↑ Clark, Ross (1994). "Moriori and Māori: The Linguistic Evidence". In Sutton, Douglas. The Origins of the First New Zealanders. Auckland: Auckland University Press. pp. 123–135.

- ↑ Davis, Denise; Solomon, Māui. "Moriori – The impact of new arrivals". Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 29 April 2010.

- ↑ Ingram, C. W. N. (1984). New Zealand Shipwrecks 1975–1982. Auckland: New Zealand Consolidated Press; pp 3–6, 9, 12.

- ↑ R Bennett. Treaty to Treaty. 2007. P 193.

- ↑ "The Boyd incident". Ministry for Culture and Heritage. 11 March 2014. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- ↑ Ballara, Angela (30 October 2012). "Pomare II". Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- ↑ "Pakeha-Maori", New Zealand History online

- ↑ Phillips, Jock (1 August 2015). "History of immigration - A growing settlement: 1825 to 1839". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- ↑ Swarbrick, Nancy (June 2010). "Creative life – Writing and publishing". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 22 January 2011.

- ↑ "The Māori Messenger: Te Karere Māori". Papers Past. Retrieved 2018-07-13.

- ↑ McMillan, Kate (2012-06-20). "Te Karere o Nui Tireni, 1842". teara.govt.nz. Retrieved 2018-07-13.

- ↑ 1966 Encyclopaedia of New Zealand

- ↑ Entwisle, Peter (20 October 2006). "Estimating a population devastated by epidemics". Otago Daily Times. Archived from the original on 14 October 2008. Retrieved 13 May 2008.

- ↑ Pool, D. I. (March 1973). "Estimates of New Zealand Maori Vital Rates from the Mid-Nineteenth Century to World War I". Population Studies. Population Investigation Committee. 27 (1): 117–125. doi:10.2307/2173457. JSTOR 2173457. PMID 11630533.

- ↑ Hiroa, Te Rangi (1910). Medicine Amongst the Maoris, in Ancient and Modern Times. Dunedin: Otago University, PhD Thesis. pp. 82–83. Retrieved 16 September 2010.

- ↑ Thompson, Christina A. (June 1997). "A dangerous people whose only occupation is war: Maori and Pakeha in 19th century New Zealand". Journal of Pacific History. 32 (1): 109–119. doi:10.1080/00223349708572831. Retrieved 15 June 2008.

Whole tribes sometimes relocated to swamps where flax grew in abundance but where it was unhealthy to live. Swamps were ideal places for the breeding of the TB bacillus.

- ↑ Orange, Claudia; Williams, Bridget (1987). The Treaty of Waitangi. p. 57.

- ↑ Orange, Claudia (20 June 2012). "Treaty of Waitangi - Creating the Treaty of Waitangi". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ↑ "Te Wherowhero". Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ↑ Orange, Claudia (20 June 2012). "Treaty of Waitangi - Interpretations of the Treaty of Waitangi". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ↑ Orange, Claudia; Williams, Bridget (1987). The Treaty of Waitangi.

- ↑ "Differences between the texts". Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ↑ Te Puea.M King.Reed.2003. P 59.

- ↑ M.King, History of NZ, Penguin 2012. P41

- ↑ "The Day the Bank was Razed", Waikato Times, Tom O'Conner, P14, Oct 2012

- ↑ "Te Peeke o Aotearoa", NZJH

- ↑ History Of NZ, M. King. Penguin, 2012. P258

- ↑ King (2003), p. 224

- ↑ Te Rangi Hiroa (Sir Peter Buck) (1949). "6 – Sickness and Health". The Coming of the Maori. III. Social Organization. p. 414.

- ↑ "Population – Factors and Trends", An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand, edited by A. H. McLintock, published in 1966. Te Ara – The Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 18 September 2007. Retrieved 18 September 2007.

- ↑ The Maori Population of New Zealand: 1769-1971. David Ian Pool, 1971. ISBN 0196479479, 9780196479477

- ↑ "Māori and the Vote". Elections New Zealand. Archived from the original on 8 February 2013. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ↑ Owners of land worth at least £50, or payers of a certain amount in yearly rental (£10 for farmland or a city house, or £5 for a rural house)

- ↑ M King. Hist of New Zealand, Penguin. 2012. P 257

- ↑ "Young Maori Party | Maori cultural association". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- ↑ Te Puea. M. King. 2003. Reed. Pp. 157–161.

- ↑ "Pioneer Battalion". Ministry for Culture and Heritage. 6 April 2016. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- ↑ "Resistance to conscription". Ministry for Culture and Heritage. 17 May 2017. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- ↑ Te Puea. M King. Reed 2003. Pp. 77–100 "Conscription and Pai Marire."

- ↑ Treaty of Waitangi. An explanation. NZETC. Sir Āpirana Ngata. 1922. P13

- 1 2 "Response to war – Māori and the Second World War". Ministry for Culture and Heritage. 14 March 2018. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- ↑ "Story of the 28th – Desert Fighters". 28maoribattalion.org.nz. Government of New Zealand.

- 1 2 "Maori and the Second World War". Ministry for Culture and Heritage. 5 August 2014.

- 1 2 Sorrenson (1997), pp 339–41

- ↑

"Māori – Urbanisation and renaissance". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

The Māori renaissance since 1970 has been a remarkable phenomenon.

- ↑ "Time Line of events 1950–2000". Schools @ Look4.

- ↑ "Waitangi Tribunal created". Ministry for Culture and Heritage. 19 January 2017. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- ↑ "Waitangi Tribunal's recommendations frequently ignored - UN". Scoop News. 4 April 2018. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- 1 2 "The Origins of the Māori Seats". 31 May 2009. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- ↑ Tahana, Yvonne (25 June 2008). "Iwi 'walks path' to biggest ever Treaty settlement". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 8 September 2012. Retrieved 26 June 2008.

- ↑ James, Colin (6 September 2005). "Ethnicity takes its course despite middle-class idealism". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 19 October 2011.

- 1 2 Statistics New Zealand. "2013 Census QuickStats About Māori". Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- ↑ "Ethnic group (detailed single and combination) by age group and sex, for the census usually resident population count, 2013 -- NZ.Stat". Statistics New Zealand. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- ↑ "Māori Descent". Statistics New Zealand. Missing or empty

|url=(help);|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ Hamer, Paul (2012), Māori in Australia: An Update from the 2011 Australian Census and the 2011 New Zealand General Election, SSRN 2167613

- ↑ "Sharples suggests Maori seat in Australia". Television New Zealand. 1 October 2007. Retrieved 9 January 2011.

- ↑ New Zealand-born figures from the 2000 U.S. Census; maximum figure represents sum of "Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander" and people of mixed race. United States Census Bureau (2003)."Census 2000 Foreign-Born Profiles (STP-159): Country of Birth: New Zealand" (PDF). (103 KB). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau.

- ↑ Howe (2006), pp 25–40

- ↑ "Te Tipunga: 1300 – 1500", Te Papa

- ↑ Howe (2003), p. 161

- ↑ Schwimmer, E. G. (September 1961). "Warfare of the Maori". Te Ao Hou.

- ↑ (Teeterree in traditional orthography)

- ↑ Words Between Us. A.Jones. K Jenkins. Huia 2011.P150

- ↑ "New Zealand – International Religious Freedom Report 2007". U.S. State Department. Retrieved 29 April 2010.

- ↑ "Kia Ora Aotearoa". CPI Financial. August 2007. Retrieved 29 April 2010.

- ↑ Hume, Tim. "Muslim faith draws converts from NZ prisons." Star Times

- ↑ Onnudottir, Helena; Possamai, Adam; Turner, Bryan (2012). "Islam and Indigenous Populations in Australia and New Zealand". Muslims in the West and the Challenges of Belonging: 60–86. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- ↑ "2013 Census QuickStats about culture and identity – tables". Statistics New Zealand. 15 April 2014. Retrieved 18 July 2015.

- ↑ Diamond, Paul (5 March 2010). "Te tāpoi Māori—Māori tourism—Preserving culture". Te Ara—the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 18 May 2010.

- ↑ Swarbrick, Nancy (3 March 2009). "Creative life – Performing arts". Te Ara—the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 18 May 2010.

- ↑ Baillie, Russell (24 January 2006). "Other NZ hits eat dust of 'Fastest Indian'". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 22 August 2009.

- ↑ "Aramoana film cracks $1 million". The New Zealand Herald. 14 December 2006. Retrieved 22 August 2009.

- ↑ "Awards for Once Were Warriors". IMDb. Retrieved 22 August 2009.

- ↑ "Details.cfm - Emanuel Levy".

- ↑ Derby, Mark (December 2010). "Māori–Pākehā relations – Sports and race". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 4 February 2011.

- ↑ "43 Māori athletes to head to Rio Olympics". Television New Zealand. 5 August 2016. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- ↑ Jones, Renee (8 October 2005). "McDonald's adopts obscure Maori ball game". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 30 July 2007.

- ↑ Joyce, B. and Mathers, B. (2006). Whakapapa. An introduction to Maori family history research. Published by the Maori Interest Group of the NZSG Inc.

- ↑ He Korero. A.Jones and K.Jenkins. Huia.2011

- ↑ "Kohanga Reo". Kiwi Family Media. Retrieved 29 June 2017.

- ↑ "Māori Television Launch | Television". www.nzonscreen.com. NZ On Screen. Retrieved 29 June 2017.

- ↑ "QuickStats About Māori". Statistics New Zealand. 2006. Retrieved 14 November 2007. (revised 2007)

- ↑ "2013 Census QuickStats about Māori". Statistics New Zealand. 3 December 2013. Archived from the original on 12 July 2017. Retrieved 29 June 2017.

- ↑ King (1996), pp 37, 43

- 1 2 King (1996), pp 42–3

- ↑ Taonui, Rāwiri (4 March 2009). "Tribal organisation". Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

- ↑ King (1996), pp 46–7, 73–5

- ↑ King (1996), pp 195–6

- ↑ Hill (2009), pp 519–29

- ↑ The Quest for security in New Zealand 1840 to 1966 by William Ball Sutch

- ↑ Mead (2003), pp 212–3

- ↑ Mead (2003), pp 95–100, 215–6

- ↑ Maori Health Web Page: Socioeconomic Determinants of Health–Deprivation. Retrieved 12 June 2007.

- ↑ "Over-representation of Maori in the criminal justice system" (PDF). Department of Corrections. September 2007. p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 December 2010.

- ↑ Department of Labour, NZ Archived 11 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine., Māori Labour Market Outlook

- ↑ University of Otago, NZ, Suicide Rates in New Zealand–Exploring Associations with Social and Economic Factors

- ↑ Scoop.co.nz, Flavell: Maori Education – not achieved

- ↑ "What drives Hekia Parata?". 6 October 2012 – via Stuff.co.nz.

- ↑ Cslbiotherapies.co.nz Archived 23 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine.,Who gets Cervical Cancer?

- ↑ Diabetes in New Zealand – Models And Forecasts 1996–2011

- ↑ PubMed Maori Health Issues

- ↑ webmaster@msd.govt.nz. "Social Report 2004 - Health - Life Expectancy". www.socialreport.msd.govt.nz.

- ↑ "Gap closing in life expectancy". 3 News NZ. April 16, 2013.

- ↑ "Mana Māori" Archived 14 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine.. Community Action Toolkit to Prevent Family Violence Information Sheet #30 (p. 40). Retrieved 16 July 2009.

- ↑ King (1999), p. 468

- ↑ Lashley (2006), pp 131–3

- ↑ Policy, Strategy and Research Group, Department of Corrections (September 2007). "Over-representation of Māori in the criminal justice system: An exploratory report" (PDF). Department of Corrections (New Zealand). Retrieved 23 May 2017.

- ↑ "The Treaty of Waitangi debate". TVNZ. 15 October 2011. Archived from the original on 1 March 2012. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- ↑ Ford, Chris (24 April 2006). "Race relations in New Zealand". Global Politician. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- ↑ "Waka Umanga : A Proposed Law for Maori Governance Entities – NZLC R". Law Commission. 8 June 2006. Archived from the original on 21 June 2011. Retrieved 16 October 2010.

- ↑ "Waka Umanga (Maori Corporations) Bill – NZLC MP 15". Auckland District Law Society. 31 May 2007. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 8 June 2007.

- ↑ New Zealand Human Rights Commission (March 2010). Tūi Tūi Tuituiā: Race relations in 2009 (PDF) (Report). ISSN 1178-7724. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 November 2010. Retrieved 5 November 2010.

- ↑ Crewdson, Patrick (2 July 2006). "Iwi claim to All Black haka turned down". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ↑ "New Zealand - Maori Flags". www.crwflags.com.

- ↑ "Te Kotahitanga – the Māori Parliament". Ministry of Women's Affairs. 16 September 2010. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 5 November 2010.

- ↑ Tahana, Yvonne (29 September 2008). "National to dump Maori seats in 2014". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 28 December 2009.

- ↑ "Maori Party drops push to entrench Maori seats". RNZ. 17 November 2008. Retrieved 5 March 2016.

- ↑ Edwards, Bryce (26 September 2017). "Political Roundup: The emotional Maori Party demise". Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ↑ "Uncovering the Maori mystery". BBC Sport. 5 June 2003.

Bibliography

- Hill, Richard S (2009). "Maori and State Policy". In Byrnes, Giselle. The New Oxford History of New Zealand. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-558471-4.

- Howe, K. R. (2003). The quest for origins: who first discovered and settled the Pacific islands?. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-14-301857-4.

- Howe, Kerry (2006). "Ideas of Māori Origins". In Māori Peoples of New Zealand: Ngā Iwi o Aotearoa. Te Ara – The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Auckland: David Bateman.

- Irwin, Geoffrey (2006). "Pacific Migrations". In Māori Peoples of New Zealand: Ngā Iwi o Aotearoa. Te Ara – The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Auckland: David Bateman.

- King, Michael (1996). Maori: A Photographic and Social History (2nd ed.). Auckland: Reed Publishing. ISBN 0-7900-0500-X.

- King, Michael (2003). The Penguin History of New Zealand. Penguin. ISBN 0-14-301867-1.

- Lashley, Marilyn E. (2006). "Remedying Racial and Ethnic Inequality in New Zealand: Reparative and Distributive Policies of Social Justice". In Myers, Samuel L.; Corrie, Bruce P. Racial and ethnic economic inequality: an international perspective, volume 1996. New York: Peter Lang. ISBN 0-8204-5656-X.

- McIntosh, Tracey (2005), 'Maori Identities: Fixed, Fluid, Forced', in James H. Liu, Tim McCreanor, Tracey McIntosh and Teresia Teaiwa, eds, New Zealand Identities: Departures and Destinations, Wellington: Victoria University Press

- Mead, Hirini Moko (2003). Tikanga Māori: living by Māori values. Wellington: Huia Publishers. ISBN 1-877283-88-6.

- Orange, Claudia (1989). The Story of a Treaty. Wellington: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 0-04-641053-8.

- Sorrenson, M. P. K (1997). "Modern Māori: The Young Maori Party to Mana Motuhake". In Sinclair, Keith. The Oxford Illustrated History of New Zealand (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-558381-7.

Further reading

- Ballara, Angela (1998). Iwi: the dynamics of Māori tribal organisation from c. 1769 to c. 1945. Wellington: Victoria University Press. ISBN 0-86473-328-3.

- Biggs, Bruce (1994). "Does Māori have a closest relative?" In Sutton (Ed.)(1994), pp. 96–105.

- Gagne, Natacha. Being Maori in the City: Indigenous Everyday Life in Auckland (University of Toronto Press; 2013) 368 pages;

- Hiroa, Te Rangi (Sir Peter Buck) (1974). The Coming of the Māori. Second edition. First published 1949. Wellington: Whitcombe and Tombs.

- Irwin, Geoffrey (1992). The Prehistoric Exploration and Colonisation of the Pacific. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mclean, Mervyn (1996). "Maori Music". Auckland : Auckland University Press.

- Simmons, D.R. (1997). Ta Moko, The Art of Māori Tattoo. Revised edition. First published 1986. Auckland: Reed

- Sutton, Douglas G. (Ed.) (1994). The Origins of the First New Zealanders. Auckland: Auckland University Press. ISBN 1-86940-098-4

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Māori. |

- Entry on the Māori people in Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand

- Māori people at Curlie (based on DMOZ)